Wuchereria bancrofti

Wuchereria bancrofti is one of the mosquito-borne filarial nematode that causes lymphatic filariasis 1. The other filarial nematodes are Brugia malayi and Brugia timori. Wuchereria bancrofti, Brugia malayi, and Brugia timori are considered human parasites as animal reservoirs are of minor epidemiologic importance or absent; felid species and some primates are the primary reservoir hosts of zoonotic Brugia pahangi. The typical vector for Brugia spp. filariasis are mosquito species in the genera Mansonia and Aedes. Wuchereria bancrofti is transmitted by many different mosquito genera/species, depending on geographical distribution. Among them are Aedes spp., Anopheles spp., Culex spp., Mansonia spp., and Coquillettida juxtamansonia.

Wuchereria bancrofti was once widespread in tropical regions globally but control measures have reduced its geographic range. Wuchereria bancrofti is currently endemic throughout Sub-Saharan Africa (excluding the southern portion of the continent), Madagascar, several Western Pacific Island nations and territories and parts of the Caribbean. Bancroftian filariasis also occurs sporadically in South America, India, and Southeast Asia.

Lymphatic filariasis is a parasitic disease caused by three species of microscopic, thread-like worms. The adult worms only live in the human lymph system. The lymph system maintains the body’s fluid balance and fights infections. An estimated 90% of lymphatic filariasis cases are caused by Wuchereria bancrofti also known as Bancroftian filariasis.

Lymphatic filariasis affects over 120 million people in 72 countries throughout the tropics and sub-tropics of Asia, Africa, the Western Pacific, and parts of the Caribbean and South America. You cannot get infected with the worms in the United States.

The clinical expression of lymphatic filariasis varies considerably. Most infected persons are asymptomatic. Even in asymptomatic people, adult filarial worms commonly cause subclinical lymphatic dilatation and dysfunction. Filarial lymphadenopathy is seen commonly in infected children; before puberty, adult worms can be detected by ultrasonography of the inguinal, crural, and axillary lymph nodes and vessels. Death of the adult worm triggers an acute inflammatory response, which progresses distally (retrograde) along the affected lymphatic vessel, usually in the limbs and is termed acute filarial lymphangitis. If present, systemic symptoms, such as headache or fever, are generally mild.

In postpubertal males, adult Wuchereria bancrofti organisms are found most commonly in the intrascrotal lymphatic vessels and can be visualized on ultrasound examination. Inflammation resulting from adult worm death, in this area, may present as funiculitis, epididymitis, or orchitis. A tender granulomatous nodule may be palpable at the site of the dead adult worms.

The chronic manifestations of lymphedema and/or hydrocele will develop in approximately 30% of lymphatic filariasis-infected persons. Lymphedema mostly affects the legs, but can also occur in the arms, breasts, and genitalia. Most people develop these symptoms years after infection has cleared. Recurrent secondary bacterial infections of the affected extremity, characterized by severe pain, fever and chills, hasten the progression of lymphedema to its advanced stage, known as elephantiasis.

Filarial hydrocele is thought to be the consequence of lymphatic damage caused by adult worms. Chyluria, which results from rupture of dilated lymphatics into the renal pelvis, can occur as a manifestation of bancroftian filariasis. Microscopic hematuria and proteinuria are also found in lymphatic filariasis infected patients.

Cough, fever, marked eosinophilia, high serum immunoglobulin E (IgE) concentrations, and positive antifilarial antibodies are manifestations of the tropical pulmonary eosinophilia syndrome. Peripheral microfilaremia is absent in patients with tropical pulmonary eosinophilia. Most cases of tropical pulmonary eosinophilia have been reported in long-term residents from Asia. Men 20 to 40 years old are most commonly affected.

People infected with adult worms can take a yearly dose of medicine, called diethylcarbamazine (DEC), that kills the microscopic worms circulating in the blood. While this drug does not kill all of the adult worms, it does prevent infected people from giving the disease to someone else.

People with lymphedema and elephantiasis are not likely to benefit from diethylcarbamazine treatment because most people with lymphedema are not actively infected with the filarial parasite. Physicians can obtain diethylcarbamazine (DEC) from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) after lab results confirm infection.

People with lymphedema and hydrocele can benefit from lymphedema management, and in the case of hydrocele surgical repair. Even after the adult worms die, lymphedema can develop. You can ask your physician for a referral to see a lymphedema therapist for specialized care. Prevent the lymphedema from getting worse by following several basic principles:

- Carefully wash and dry the swollen area with soap and water every day.

- Elevate the swollen arm or leg during the day and at night to move the fluid.

- Perform exercises to move the fluid and improve lymph flow.

- Disinfect any wounds. Use antibacterial or antifungal cream if necessary.

- Wear shoes adapted to the size of the foot to protect the feet from injury.

Men with hydrocele can undergo surgery to reduce the size of the scrotum.

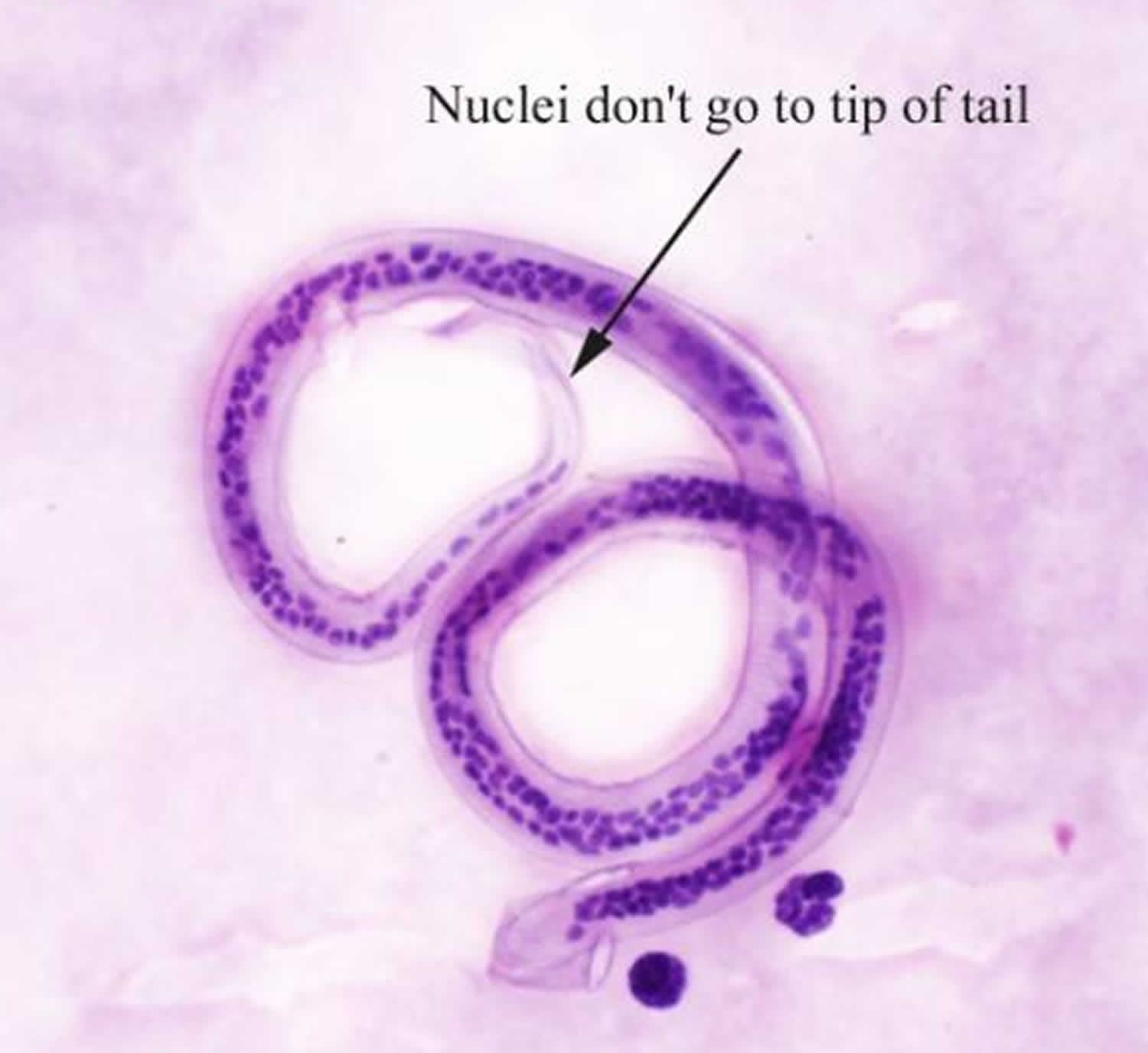

Figure 1. Wuchereria bancrofti

Footnote: Shows Wuchereria bancrofti in thick smear

[Source 2 ]Who is at risk of lymphatic filariasis?

Repeated mosquito bites over several months to years are needed to get lymphatic filariasis. People living for a long time in tropical or sub-tropical areas where the disease is common are at the greatest risk for infection. Short-term tourists have a very low risk. An infection will show up on a blood test.

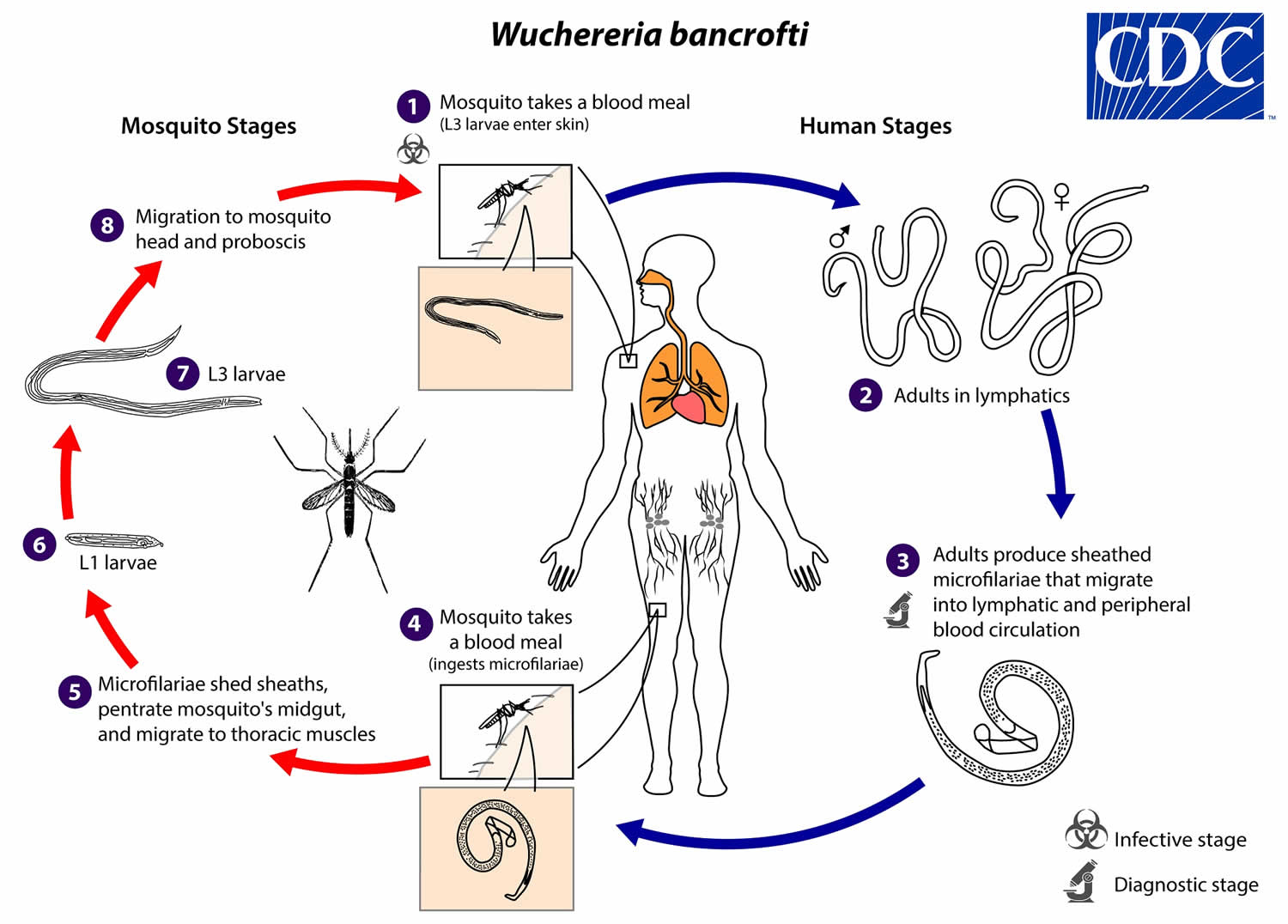

Wuchereria bancrofti life cycle

During a blood meal, an infected mosquito introduces third-stage filarial larvae onto the skin of the human host, where they penetrate into the bite wound (number 1). They develop in adults that commonly reside in the lymphatics (number 2). The female worms measure 80 to 100 mm in length and 0.24 to 0.30 mm in diameter, while the males measure about 40 mm by 1 mm. Adults produce microfilariae measuring 244 to 296 μm by 7.5 to 10 μm, which are sheathed and have nocturnal periodicity, except the South Pacific microfilariae which have the absence of marked periodicity. The microfilariae migrate into lymph and blood channels moving actively through lymph and blood (number 3). A mosquito ingests the microfilariae during a blood meal (number 4). After ingestion, the microfilariae lose their sheaths and some of them work their way through the wall of the proventriculus and cardiac portion of the mosquito’s midgut and reach the thoracic muscles (number 5). There the microfilariae develop into first-stage larvae (number 6) and subsequently into third-stage infective larvae (number 7). The third-stage infective larvae migrate through the hemocoel to the mosquito’s prosbocis (number 8) and can infect another human when the mosquito takes a blood meal (number 1).

Figure 2. Wuchereria bancrofti life cycle

Wuchereria bancrofti prevention

The best way to prevent lymphatic filariasis is to avoid mosquito bites. The mosquitoes that carry the microscopic worms usually bite between the hours of dusk and dawn . If you live in an area with lymphatic filariasis:

- At night

- Sleep in an air-conditioned room or

- Sleep under a mosquito net

- Between dusk and dawn

- Wear long sleeves and trousers and

- Use mosquito repellent on exposed skin.

Another approach to prevention includes giving entire communities medicine that kills the microscopic worms — and controlling mosquitoes. Annual mass treatment reduces the level of microfilariae in the blood and thus, diminishes transmission of infection. This is the basis of the Global Programme to Eliminate Lymphatic Filariasis.

Experts consider that lymphatic filariasis, a neglected tropical disease, can be eliminated globally and a global campaign to eliminate lymphatic filariasis as a public health problem is under way. The elimination strategy is based on annual treatment of whole communities with combinations of drugs that kill the microfilariae. As a result of the generous contributions of these drugs by the companies that make them, hundreds of millions of people are being treated each year . Since these drugs also reduce levels of infection with intestinal worms, benefits of treatment extend beyond lymphatic filariasis. Successful campaigns to eliminate lymphatic filariasis have taken place in China and other countries.

Wuchereria bancrofti disease

Lymphatic filariasis disease spreads from person to person by mosquito bites. When a mosquito bites a person who has lymphatic filariasis, microscopic worms circulating in the person’s blood enter and infect the mosquito. When the infected mosquito bites another person, the microscopic worms pass from the mosquito through the skin, and travel to the lymph vessels. In the lymph vessels they grow into adults. An adult worm lives for about 5–7 years. The adult worms mate and release millions of microscopic worms, called microfilariae, into the blood. People with the worms in their blood can give the infection to others through mosquitoes.

Although the parasite damages the lymph system , most infected people have no symptoms and will never develop clinical symptoms. These people do not know they have lymphatic filariasis unless tested. Lymphangitis, lymphadenopathy, and eosinophilia may accompany infection in the early stages. A small percentage of persons will develop lymphedema. This is caused by fluid collection because of improper functioning of the lymph system resulting in swelling. This mostly affects the legs, but can also occur in the arms, breasts, and genitalia. Most people develop these symptoms years after being infected.

The swelling and the decreased function of the lymph system make it difficult for the body to fight germs and infections. These people will have more bacterial infections in the skin and lymph system. This causes hardening and thickening of the skin, which is called elephantiasis. Many of these bacterial infections can be prevented with appropriate skin hygiene as well as skin and wound care .

Men can develop hydrocele or swelling of the scrotum due to infection with one of the parasites that causes lymphatic filariasis specifically Wuchereria bancrofti.

Filarial infection can also cause tropical pulmonary eosinophilia syndrome, although this syndrome is typically found in persons living with the disease in South and Southeast Asia. Eosinophilia is the presence of higher than normal disease-fighting white blood cells in the body. Symptoms of tropical pulmonary eosinophilia syndrome include cough, bloody sputum, shortness of breath, wheezing, chest pain, splenomegaly, peripheral hypereosinophilia and eosinophilic pulmonary infiltrate. The eosinophilia is often accompanied by high levels of Immunoglobulin E ( IgE) and antifilarial antibodies.

Wuchereria bancrofti symptoms

Most infected people are asymptomatic and will never develop clinical symptoms, despite the fact that the parasite damages the lymph system. A small percentage of persons will develop lymphedema or, in men, a swelling of the scrotum called hydrocele . Lymphedema is caused by improper functioning of the lymph system that results in fluid collection and swelling. This mostly affects the legs, but can also occur in the arms, breasts, and genitalia. Most people develop these clinical manifestations years after being infected.

The swelling and the decreased function of the lymph system make it difficult for the body to fight germs and infections. Affected persons will have more bacterial infections in the skin and lymph system. This causes hardening and thickening of the skin, which is called elephantiasis. Many of these bacterial infections can be prevented with appropriate skin hygiene and care for wounds.

Men can develop hydrocele or swelling of the scrotum due to infection with one of the species of parasites that causes lymphatic filariasis, specifically Wuchereria bancrofti.

Filarial infection can also cause tropical pulmonary eosinophilia syndrome. Eosinophilia is a higher than normal level of disease-fighting white blood cells, called eosinophils. This syndrome is typically found in infected persons in Asia. Clinical manifestations of tropical pulmonary eosinophilia syndrome include cough, shortness of breath, and wheezing. The eosinophilia is often accompanied by high levels of Immunoglobulin E ( IgE) and antifilarial antibodies.

Wuchereria bancrofti diagnosis

The standard method for diagnosing active infection is the identification of microfilariae in a blood smear by microscopic examination. Microfilariae can be detected microscopically on blood smears obtained at night (10 PM–2 AM). The microfilariae that cause lymphatic filariasis circulate in the blood at night (called nocturnal periodicity). Blood collection should be done at night to coincide with the appearance of the microfilariae, and a thick smear should be made and stained with Giemsa or hematoxylin and eosin. For increased sensitivity, concentration techniques can be used.

Serologic enzyme immunoassay tests, including antifilarial IgG1 and IgG4, provide an alternative to microscopic detection of microfilariae for the diagnosis of lymphatic filariasis. Patients with active filarial infection typically have elevated levels of antifilarial IgG4 in the blood and these can be detected using routine assays.

Assays for circulating parasite antigen of Wuchereria bancrofti are not presently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration.

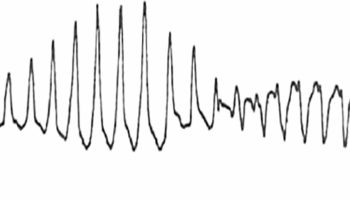

Other methods of diagnosis include: tissue specimens to visualize adult worms or microfilariae as well as ultrasonography which allows visualization of adult worms (ultrasonography demonstration can be found at 3.

Because lymphedema may develop many years after infection, lab tests are most likely to be negative with these patients.

Wuchereria bancrofti treatment

Patients currently infected with the parasite

Diethylcarbamazine (DEC) is the drug of choice in the United States 4. The drug kills the microfilariae and some of the adult worms. Diethylcarbamazine has been used world-wide for more than 50 years. Because this infection is rare in the U.S., the drug is no longer approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and cannot be sold in the U.S. Physicians can obtain the medication from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) after confirmed positive lab results. CDC gives the physicians the choice between 1 or 12-day treatment of diethylcarbamazine (6 mg/kg/day). One day treatment is generally as effective as the 12-day regimen. Diethylcarbamazine is generally well tolerated. Side effects are in general limited and depend on the number of microfilariae in the blood. The most common side effects are dizziness, nausea, fever, headache, or pain in muscles or joints.

Diethylcarbamazine should not be administered to patients who may also have onchocerciasis as diethylcarbamazine can worsen onchocercal eye disease. In patients with loiasis, diethylcarbamazine can cause serious adverse reactions, including encephalopathy and death. The risk and severity of the adverse reactions are related to Loa loa microfilarial density.

In settings where onchoceriasis is present, Ivermectin is the drug of choice to treat lymphatic filariasis.

Some studies have shown adult worm killing with treatment with doxycycline (200mg/day for 4–6 weeks).

Patients with clinical symptoms

People with lymphedema and elephantiasis are unlikely to benefit from DEC treatment because most people with lymphedema are not actively infected with the filarial parasite.

To prevent lymphedema from getting worse, patients should ask their physician for a referral to a lymphedema therapist so they can be informed about some basic principles of care such as hygiene, elevation, exercises,skin and wound care, and wearing appropriate shoes.

Patients with hydrocele may have evidence of active infection, but typically do not improve clinically following treatment with diethylcarbamazine (DEC). The treatment for hydrocele is surgery.

There is some evidence that suggests that a course of the antibiotic doxycycline may prevent lymphedema from getting worse.

Care of patients with lymphedema, elephantiasis, or hydrocele

Lymphedema and elephantiasis are not indications for diethylcarbamazine (DEC) treatment because most people with lymphedema are not actively infected with the filarial parasite and lab tests are generally negative in these patients.

To prevent the lymphedema from worsening, physicians should consider referring lymphedema patients to a certified lymphedema therapist so patients can be informed about basic principles of care such as hygiene, exercise, elevation, treatment of wounds and infections, and use of appropriate footwear. Complex decongestive physiotherapy can be effective for treating lymphedema. The National Lymphedema Network (https://lymphnet.org/) lists certified lymphedema therapists and lymphedema organizations in the U.S.

There is limited evidence to suggest that a 4-6 week course of doxycycline (200 mg / day) may stabilize or reverse the progression of disease in persons with lymphedema.

Patients with hydrocele may have evidence of active infection, but typically do not improve clinically following treatment with diethylcarbamazine (DEC). The treatment for hydrocele is surgery (hydrocelectomy).

- Parasites – Lymphatic Filariasis Causative Agents. https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/lymphaticfilariasis/biology.html[

]

- Singh, Gurjeet & Raksha, & Urhekar, A. (2013). Advanced Techniques for Detection of Filariasis -A Review. International Journal of Research Studies in Biosciences. 1. 17-22. [

]

- Mand, S., Marfo-Debrekyei, Y., Dittrich, M. et al. Animated documentation of the filaria dance sign (FDS) in bancroftian filariasis. Filaria J 2, 3 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2883-2-3[

]

- Parasites – Lymphatic Filariasis Treatment. https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/lymphaticfilariasis/treatment.html[

]