Cheilitis granulomatosa

Cheilitis granulomatosa also called granulomatous cheilitis or Miescher’s cheilitis, is a cosmetically disturbing and persistent, idiopathic (unknown), diffuse, soft-to-firm swelling of one or both lips 1. Cheilitis granulomatosa is thought to be a subset of orofacial granulomatosa and is frequently used in the literature to describe the monosymptomatic presentation of Miescher cheilitis 2. Cheilitis granulomatosa is one manifestation of orofacial granulomatosis, which is a clinical entity describing facial and oral swelling in the setting of non-caseating granulomatous inflammation and in the absence of systemic disease such as Crohn’s disease and sarcoidosis 3. Cheilitis granulomatosa can occur by itself or as part of the Melkersson–Rosenthal syndrome, which includes relapsing peripheral facial nerve paralysis and a plicated or fissured tongue (lingua plicata). Most of the cases of Melkersson–Rosenthal syndrome present with partial symptoms. Cheilitis granulomatosa is the most common monosymptomatic form of Melkersson–Rosenthal syndrome 4.

Cheilitis granulomatosa is a rare disease of undefined incidence and prevalence. Cheilitis granulomatosa has no predisposition to race, sex, or age and the incidence has been estimated at 0.08 % in the general population 5. It may have an onset in all age groups, but most commonly seen in adults with peak incidence reported between 20 to 40 years of age. It rarely affects children. However, in two recently published articles, 30 cases in pediatric patients have been described. Most of the literature suggests an equal sex distribution; however, some authors reported that it is more frequently reported in females. Rare familial cases have also been reported. The first episode typically subsides in hours or days, but both the frequency and duration of the attacks increase until they become persistent. The upper lip, lower lip, or both lips can be involved.

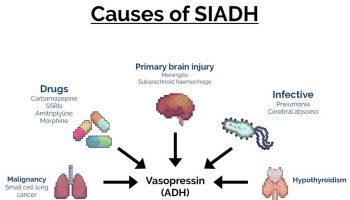

The exact cause of cheilitis granulomatosa is unknown. However, factors including allergy to foods and medication, contact allergy, genetic predisposition and infection have been implicated 6. Other proposed causes of orofacial granulomatosis include dietary allergens such as cinnamon and benzoates 7. Similar orofacial swelling may be an early manifestation of Crohn’s disease or sarcoidosis, and so clinical history is important in diagnosis. The cause of cheilitis granulomatosa has not been wholly elucidated, but a current hypothesis holds that a random influx of inflammatory cells is responsible. Other granulomatous and edematous causes of lip swelling must be investigated prior to diagnosis.

The differential diagnosis of persistent upper lip swelling includes other granulomatous diseases such as a foreign body reaction, mycobacterial infection, sarcoidosis, Crohn’s disease, Wegener’s granulomatosis, and histoplasmosis; amyloidosis; rosacea; medications such as ACE inhibitors and calcium channel blockers; atopic reaction to a wide variety of allergens; and hereditary diseases such as C1 esterase deficiency 1. There has, in fact, been an association noted between cheilitis granulomatosa and Crohn’s disease 8 although Crohn’s disease is more likely to present with oral ulcers and hematological markers of inflammation than simple lip swelling 9.

There is no definitive treatment for cheilitis granulomatosa, and this is complicated by the poorly understood mechanism of disease. Options for treatment include dietary modifications, antibiotics, systemic or intralesional corticosteroids, and surgery, although treatment is not always necessary.

Corticosteroids are widely used for cheilitis granulomatosa and have been shown to be effective in reducing facial swelling and preventing recurrence 3, but have side effects when used long-term. Bacci et Valente had excellent success in one patient with intralesional injections of 40 mg triamcinolone once a week for a total of three administrations; there was rapid improvement with no recurrence at 1, 3, 6, or 12 months followup 10.

Cheilitis granulomatosa causes

The cause of granulomatous cheilitis is still unknown 11. Several causes of different orders have been proposed: genetic, inflammatory, allergic, and microbial 12. There is not a clear etiological mechanism 13. Normal lip architecture is altered by lymphedema and noncaseating granulomas in the lamina propria. Excessive permeability of facial cutaneous vessels resulting from abnormal regulation of the autonomic nervous system has been suggested as a potential cause. Hornstein 14 proposed that nonspecific antigens may stimulate perivascular cells to form granulomas, causing obstruction of the vessels and subsequent facial swelling.

Dietary or other antigens are the most common identified cause of orofacial granulomatosis 15. Contact antigens such as cobalt, gold, or mercury are sometimes implicated 16. Orofacial granulomatosis may also result from reactions to some foods or medicaments, particularly cinnamon aldehyde and benzoates, but also butylated hydroxyanisole, dodecyl gallate, menthol, and monosodium glutamate 17. Expression of protease-activated receptor 1 and 2 occurs in orofacial granulomatosis. Th1 immunocytes produce interleukin 12 and RANTES/MIP-1alpha and granulomas. HLA typing may show HLA A*02, HLA*A11, HLA DRB1*11, HLA DRB1*13, and HLA DQB1*03 18. Low levels of HLA A*01, HLA DRB1*04, HLA DRB1*07, and HLA DQB1*02 may be found as well 19.

Crohn disease, sarcoidosis, and orofacial granulomatosis may present with similar histologic findings. Analogous findings have also been reported after liver transplantation in children 20. Recent research has attempted to identify related genetic risk factors between Crohn disease and orofacial granulomatosis to correlate their similar clinical presentation and sometimes comorbid development 21. Missense coding in NOD2-variant patients may indicate the concurrent development of orofacial granulomatosis with intestinal disease, but not orofacial granulomatosis alone 22. Miescher-Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome is not usually related to the development of inflammatory bowel disease. However, one longitudinal study tracking 27 patients with a median follow up of 30 years found that one patient with cheilitis granulomatosa developed Crohn disease and two with Miescher-Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome developed ulcerative colitis 23. This is still an active area of research.

A genetic predisposition may exist in Miescher-Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome; siblings have been affected, and a plicated tongue may be present in otherwise unaffected relatives. Paternal and maternal inheritance has been implicated in some cases 24. A mutation in the FATP1 gene has been found in patients with Miescher-Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome 25. It may follow a pattern of autosomal dominant inheritance with the responsible gene being located on 9p 26.

A summary of possible causes of granulomatous cheilitis include 27:

- Genetics – Debate about link with HLA antigen and inheritance patterns of different subsets of the disease. Genetic origin has been suggested considering some cases with involvement of other family members; however, it remains unproven, and no HLA association has been found in patients with cheilitis granulomatosa compared to the general population.

- Food allergy – Various food additives thought to cause or precipitant event; 60% of individuals with condition are atopic (eczema, IgE levels); prime causative agents or exacerbation of disease

- Allergy to dental material – No conclusive evidence

- Infection – Studies have focused on Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Mycobacterium paratuberculosis, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, and Borrelia burgdorferi but provide insufficient evidence

- Immunological – Hypothesis that no single antigen causes disease, rather a random influx of inflammatory cells; delayed sensitivity reaction rather than super antigen; results reflect an immunological nature. Cheilitis granulomatosa is a chronic inflammatory condition characterized by a predominant T helper 1-mediated immune response. The main anomaly is probably a local alteration of innate immunity of lip mucosa in response to various antigens whose insufficient purification leads to a persistent granulomatous reaction.

- Crohn disease. Although early studies suggested that cheilitis granulomatosa may represent an extra-intestinal variant of Crohn disease with overt gastrointestinal disease developing much later, the fact that cheilitis granulomatosa is found in less than 1% patients with Crohn disease cannot be ignored.

- Sarcoidosis

- Orofacial granulomatosis

- Cancer or infection resulting in obstruction of lymphatics around the lips

- Several microbial agents have been incriminated, as eventual factors of deregulation of the immune response. Studies have included especially Mycobacterium tuberculosis and paratuberculosis, Borrelia burgdorferi, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, and Candida albicans. Nevertheless, with conflicting results, the role of these germs in the pathogenesis of cheilitis granulomatosa remains uncertain.

- Hypersensitivity to ultraviolet (UV)-B radiation.

Cheilitis granulomatosa symptoms

Cheilitis granulomatosa is usually seen in orofacial granulomatosis as an episodic nontender swelling and enlargement of one or both lips. Granulomas in Miescher cheilitis are confined to the lip. In other cases of granulomatous cheilitis, granulomatous disease is more widespread, including the periocular region and genitalia 28.

A fissured or plicated tongue is seen in 20-40% of patients. Its presence from birth (in some patients) may indicate a genetic susceptibility. Patients may lose the sense of taste and have decreased salivary gland secretion.

The first symptom of granulomatous cheilitis is a sudden swelling of the upper lip. The first episode of lip edema typically subsides completely in hours or days. Swelling of the lower lip and one or both cheeks may follow in orofacial granulomatosis. Less commonly, the forehead, eyelids, or one side of the scalp may be involved. The swelling may feel soft, firm or nodular when touched.

Recurrent attacks of granulomatous cheilitis may occur within days or even years after the first episode. After recurrent attacks, swelling may persist and slowly the swelling may become larger, eventually becoming permanent. At this time the lips may crack, bleed and heal leaving a reddish-brown colour with scaling. This can be painful. Eventually, the lip takes on the consistency of hard rubber. Recurrences can range from days to years.

Other symptoms that may accompany granulomatous cheilitis include:

- Fever, headache and visual disturbances

- Mild enlargement of regional lymph nodes in 50% of cases

- Fissured or plicated (pleat-like effect) tongue in 20–40% of cases

- Facial palsy; this can be intermittent, then possibly permanent and can be unilateral or bilateral, and partial or complete. It occurs in about 30% of cases of granulomatous cheilitis and indicates progression to orofacial granulomatosis.

Attacks sometimes are accompanied by fever and mild constitutional symptoms (eg, headache, visual disturbance). Miescher-Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome involves the association with facial nerve palsy and plicated tongue 29.

Facial palsy of the lower motor-neuron type occurs in about 30% of patients with granulomatous cheilitis. Facial palsy may precede facial swelling by months or years, but it more commonly develops later. Facial palsy is intermittent at first, but it may become permanent. It can be unilateral or bilateral, partial or complete.

Other cranial nerves (eg, olfactory, auditory, glossopharyngeal, hypoglossal) are occasionally affected.

Cheilitis granulomatosa diagnosis

Cheilitis granulomatosa diagnosis is often suspected clinically. A lip biopsy of the affected tissue is needed in most cases. However, a biopsy may not be conclusive in the earlier stages. Skin biopsy of the affected tissue shows characteristic histopathology, in which there are granulomas, i.e. a mixed inflammatory cell infiltration, in the dermis (the deeper layer of the skin).

It is important to rule out other associated diseases including Crohn disease, sarcoidosis, foreign body reaction, lymphoma, angioedema and infection.

Physical examination

The earliest manifestation of granulomatous cheilitis is sudden diffuse or occasionally nodular swellings of the lip or the face involving (in decreasing order of frequency) the upper lip, the lower lip, both lips, and one or both cheeks 30. The forehead, the eyelids, or one side of the scalp may be involved (less common) 31. As previously mentioned, a fissured or plicated tongue is seen in 20-40% of patients.

The lip swelling may feel soft, firm, or nodular on palpation. Once chronicity is established, the enlarged lip appears cracked and fissured, with reddish brown discoloration and scaling. The fissured lip becomes painful and eventually acquires the consistency of firm rubber. Swelling may regress very slowly after some years. Regional lymph nodes are enlarged (usually minimally) in 50% of patients.

Orofacial lesions of orofacial granulomatosis and of Crohn disease may include facial or labial swelling, “cobblestone” proliferation of mucosa or mucosal tags, and/or ulcers. An initial presentation of probable orofacial granulomatosis does not necessarily predict the development of Crohn disease, but this is more likely in childhood 32.

Facial palsy of the lower motor-neuron type occurs in up to 30% of patients. It can be unilateral or bilateral, partial or complete. Other cranial nerves (eg, olfactory, auditory, glossopharyngeal, hypoglossal) are occasionally affected.

Central nervous system involvement has been reported, but the significance of resulting symptoms is easily overlooked because they are very variable (sometimes simulating multiple sclerosis but often with a poorly defined association of psychiatric and neurologic features). Autonomic disturbances may occur.

Laboratory studies

Serum angiotensin-converting enzyme (SACE) testing may be performed to help exclude sarcoidosis. Patch tests may be used to help exclude reactions to metals, food additives, or other oral antigens 33; some cases of granulomatous cheilitis may be associated with such sensitivities. Allergy testing has demonstrated a high rate of sensitivity to cinnamon and benzoates in patients with orofacial granulomatosis 7. If found, avoidance of the implicated allergen is recommended. A cinnamon- and benzoate-free diet has shown to reduce oral and lip inflammatory scores at 8 weeks and has been proposed by at least one author as first-line therapy for orofacial granulomatosis 34. Therefore, such testing should be included in the workup of patients with suspected orofacial granulomatosis.

Decreased iron, hemoglobin, ferritin, folate, and elevated C-reactive protein, celiac antibodies, serum IgE, and alkaline phosphatases have been documented to be associated with orofacial granulomatosis; however, evidence is insufficient that any of these are consistent markers of the disease 21.

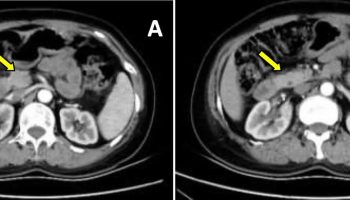

Imaging studies

Orofacial granulomatosis is the term given to granulomatous lesions similar to those of Crohn disease, found on oral biopsy, but where there is no detectable systemic Crohn disease, though this may be detected later 35. Gastrointestinal tract endoscopy, radiography, and biopsy may be used to help exclude Crohn disease. Chest radiography or gallium or positron emission tomography (PET) scanning may be performed to help exclude sarcoidosis and tuberculosis. Panorex dental films may be obtained to assess for the presence of a chronic dental abscess.

Procedures

A biopsy of the swollen lip or orofacial tissues is indicated but often shows only lymphoedema and perivascular lymphocytic infiltration during the early stages and may only later show granulomas. A biopsy may help to exclude Crohn disease, sarcoidosis, lymphoma, and other conditions in the differential diagnosis.

Histologic findings

Histologic changes are not always conspicuous or specific in many cases of long duration; the infiltrate becomes denser and pleomorphic, and small, focal, noncaseating, sarcoidal granulomas are formed that are indistinguishable from Crohn disease or sarcoidosis.

The inflammatory response is probably mediated by cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha and by protease-activated receptors (PARs), matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), and cyclo-oxygenases (COXs). There is submucosal chronic inflammation with many Th1 and mononuclear, interleukin 1–producing cells; large, active, dendritic B cells; and noncaseating granulomas 36. Small granulomas occur in the lymphatic walls in some cases. Similar changes may be present in cervical lymph nodes.

Cheilitis granulomatosa treatment

Treatment is difficult and unsatisfactory. The aim of treatment is to improve the person’s appearance and comfort. Spontaneous remission is possible, although rare.

Patients with lesions apparently restricted initially to the mouth may progress to exhibit frank intestinal Crohn disease 37. Therefore, consult a gastroenterologist, an immunologist, a dietician, and an oral medicine specialist.

In severe cases of labial swelling, medication or surgical intervention may be required, but most respond to more conservative measures 30. Exclusion of offending substances may help facial swelling resolve. Up to 40% of orofacial granulomatosis (orofacial granulomatosis) patients may have positive reactions to patch tests. Half of these benefit from antigen exclusion 38.

Extensive labial swelling can be disfiguring and have serious social consequences for the patient; therefore, changes in personal affect should be taken into consideration when choosing treatment options for patients with cheilitis granulomatosa 30. Furthermore, comorbid psychiatric diseases and other affective phenomena may be linked to relapse frequency of Miescher-Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome 39. In one case, targeted psychotherapeutic intervention resulted in both decreased relapse frequency of the syndrome and remission of depression 39.

If cheilitis granulomatosa is related to an allergy, responsible dietary components or causative substances (which can be identified through patch testing) should be avoided longterm. Granulomatous cheilitis or orofacial granulomatosis may improve with implementation of a cinnamon- and benzoate-free diet. Benefit has been reported in 54-78% of patients 40.

If there is an underlying disease, systemic treatment for this may also reduce the swelling of the lips.

Multiple therapies, alone or in combination, have been reported to be successful in individual cases. An excellent comprehensive review of current medical treatment options for cheilitis granulomatosa was recently published by Banks and Gada in the British Journal of Dermatology 41. The following measures have been reported to reduce the severity of granulomatous cheilitis in at least some cases:

- Topical, intralesional and systemic corticosteroids. Intralesional corticosteroids injected into the lips to reduce swelling. Injections need to be repeated every few months.

- Long term anti-inflammatory antibiotics, such as a six to twelve-month course of minocycline, erythromycin, penicillin or metronidazole

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

- Other systemic treatments such as methotrexate, tacrolimus, clofazimine, dapsone, sulfasalazine, ketotifen (mast cell stabilizers) and anti-TNF agents

- Surgical excision of excess tissue and radiation therapy.

Intralesional corticosteroids may be helpful in some patients 42 and their use in combination with antibacterial drugs such as metronidazole has been an effective treatment in several instances 43. Success with other treatments has been reported anecdotally, including intralesional pingyangmycin plus dexamethasone 44. Simple compression for several hours daily may produce sustained improvement. Compression devices can be worn overnight to reduce lip edema.

Table 1. Treatment options for cheilitis granulomatosa

| Drug name | Class | Administration |

|---|---|---|

| Triamcinolone | Corticosteroid | Intralesional injection 40 mg once per week for 3 weeks |

| Metronidazole | Nitroimidazole antibiotic | 1,000 mg oral daily until clinical response is noted |

| Clofazimine | Phenelzine dye derivative | 100–200 mg oral daily for 3–6 months |

| Roxithromycin | Macrolide antibiotic | 150 mg oral daily until clinical response is noted |

| Adalimumab | TNF alpha inhibitor | Subcutaneous injection: 80 mg week 1, 40 mg week 2, then 40 mg every other week until clinical response is noted |

| Combination dapsone and triamcinolone | Folic acid antagonist; corticosteroid | Oral dapsone 100 mg daily for 2 weeks followed by 50 mg daily for 25 weeks plus intralesional triamcinolone 10 mg every other week for four injections followed by once monthly for three injections |

Footnote: It should be noted that these are anecdotal and based on case reports only.

[Source 1 ]Surgical care

Surgery and radiation have been used in treating cheilitis granulomatosa. Surgery alone is relatively unsuccessful. Reduction cheiloplasty with intralesional triamcinolone and systemic tetracycline offers the best results 45. Medical therapy is necessary to maintain the results of reductive cheiloplasty during the postoperative period 30. Give corticosteroid injections periodically after surgery to avoid an exaggerated recurrence.

Nerve decompression has been successful in the treatment of recurrent facial nerve palsy 46.

Follow-up

Follow-up care is indicated particularly to exclude the development of Crohn disease and possibly ulcerative colitis.

Cheilitis granulomatosa prognosis

Swelling is typically chronic. Morbidity related to cheilitis granulomatosa depends also on whether an underlying organic disease, such as Crohn disease or sarcoidosis 47, is present. Patients, especially children and adolescents, presenting with what appears to be granulomatous cheilitis or orofacial granulomatosis should be very carefully evaluated for gastrointestinal symptoms, signs, and disease 48.

References- Critchlow WA, Chang D. Cheilitis granulomatosa: a review. Head Neck Pathol. 2014;8(2):209-213. doi:10.1007/s12105-013-0488-2 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4022933

- Nair SP. Cheilitis granulomatosa. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2016 Nov-Dec. 7 (6):561-562.

- Grave B, McCullough M, Wiesenfeld D. Orofacial granulomatosis–a 20-year review. Oral Dis. 2009;15(1):46–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2008.01500.x

- Błochowiak KJ, Kamiński B, Witmanowski H, Sokalski J. Selected presentations of lip enlargement: clinical manifestation and differentiation. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2018 Feb;35(1):18-25.

- El-Hakim M, Chauvin P. Orofacial granulomatosis presenting as persistent lip swelling: review of 6 new cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004;62(9):1114–1117. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2003.11.013

- Tilakaratne WM, Freysdottir J, Fortune F. Orofacial granulomatosis: review on aetiology and pathogenesis. J Oral Pathol Med. 2008 Apr;37(4):191-5. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2007.00591.x https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0714.2007.00591.x

- Campbell HE, Escudier MP, Patel P, Challacombe SJ, Sanderson JD, Lomer MC. Review article: cinnamon- and benzoate-free diet as a primary treatment for orofacial granulomatosis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34(7):687–701. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04792.x

- van der Waal RI, Schulten EA, van der Meij EH, van de Scheur MR, Starink TM, van der Waal I. Cheilitis granulomatosa: overview of 13 patients with long-term follow-up–results of management. Int J Dermatol. 2002;41(4):225–229. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2002.01466.x

- Campbell H, Escudier M, Patel P, Nunes C, Elliott TR, Barnard K, Shirlaw P, Poate T, Cook R, Milligan P, Brostoff J, Mentzer A, Lomer MC, Challacombe SJ, Sanderson JD. Distinguishing orofacial granulomatosis from crohn’s disease: two separate disease entities? Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17(10):2109–2115. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21599

- Bacci C, Valente ML. Successful treatment of cheilitis granulomatosa with intralesional injection of triamcinolone. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24(3):363–364. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03466.x

- Wehl G, Rauchenzauner M. A Systematic Review of the Literature of the Three Related Disease Entities Cheilitis Granulomatosa, Orofacial Granulomatosis and Melkersson – Rosenthal Syndrome. Curr Pediatr Rev. 2018. 14 (3):196-203.

- Gossman W, Agrawal M, Jamil RT, et al. Cheilitis Granulomatosa (Miescher Melkersson Rosenthal Syndrome) [Updated 2020 May 12]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470396

- Miest R, Bruce A, Rogers RS. Orofacial granulomatosis. Clin. Dermatol. 2016 Jul-Aug;34(4):505-13.

- Hornstein OP. Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome. A neuro-muco-cutaneous disease of complex origin. Curr Probl Dermatol. 1973. 5:117-56.

- Morales C, Penarrocha M, Bagan JV, Burches E, Pelaez A. Immunological study of Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome. Lack of response to food additive challenge. Clin Exp Allergy. 1995 Mar. 25(3):260-4.

- Wong GA, Shear NH. Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome associated with allergic contact dermatitis from octyl and dodecyl gallates. Contact Dermatitis. 2003 Nov. 49(5):266-7.

- White A, Nunes C, Escudier M, et al. Improvement in orofacial granulomatosis on a cinnamon- and benzoate-free diet. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006 Jun. 12(6):508-14.

- Ketabchi S, Massi D, Ficarra G, et al. Expression of protease-activated receptor-1 and -2 in orofacial granulomatosis. Oral Dis. 2007 Jul. 13(4):419-25.

- Gavioli CFB, M S Nico M, Panajotopoulos N, Rodrigues H, Rosales CB, Valente NYS, et al. A case-control study of HLA alleles in Brazilian patients with Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome. Eur J Med Genet. 2020 Feb 8. 103879.

- Saalman R, Sundell S, Kullberg-Lindh C, Lövsund-Johannesson E, Jontell M. Long-standing oral mucosal lesions in solid organ-transplanted children-a novel clinical entity. Transplantation. 2010. 89:606.

- Miest R, Bruce A, Rogers RS 3rd. Orofacial granulomatosis. Clin Dermatol. 2016 Jul-Aug. 34 (4):505-13.

- Mentzer A, Nayee S, Omar Y, Hullah E, Taylor K, Goel R, et al. Genetic Association Analysis Reveals Differences in the Contribution of NOD2 Variants to the Clinical Phenotypes of Orofacial Granulomatosis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016 Jul. 22 (7):1552-8.

- Haaramo A, Kolho KL, Pitkäranta A, Kanerva M. A 30-year follow-up study of patients with Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome shows an association to inflammatory bowel disease. Ann Med. 2019 Mar. 51 (2):149-155.

- Feng S, Yin J, Li J, Song Z, Zhao G. Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome: a retrospective study of 44 patients. Acta Otolaryngol. 2014 Sep. 134 (9):977-81.

- Xu XG, Guan LP, Lv Y, Wan YS, Wu Y, Qi RQ, et al. Exome sequencing identifies FATP1 mutation in Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017 May. 31 (5):e230-e232.

- Smeets E, Fryns JP, Van den Berghe H. Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome and de novo autosomal t(9;21)(p11;p11) translocation. Clin Genet. 1994 Jun. 45 (6):323-4.

- Cheilitis Granulomatosa Etiology. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1075333-overview#a7

- Chu Z, Liu Y, Zhang H, Zeng W, Geng S. Melkersson-Rosenthal Syndrome with Genitalia Involved in a 12-Year-Old Boy. Ann Dermatol. 2016 Apr. 28 (2):232-6.

- Khandpur S, Malhotra AK, Khanna N. Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome with diffuse facial swelling and multiple cranial nerve palsies. J Dermatol. 2006 Jun. 33(6):411-4.

- Innocenti A, Innocenti M, Taverna C, Melita D, Mori F, Ciancio F, et al. Miescher’s cheilitis: Surgical management and long term outcome of an extremely severe case. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2017. 31:241-244.

- Reddy DN, Martin JS, Potter HD. Melkersson-Rosenthal Syndrome Presenting as Isolated Eyelid Edema. Ophthalmology. 2017 Feb. 124 (2):256.

- Jennings VC, Williams L, Henson S. Orofacial granulomatosis as a presenting feature of Crohn’s disease. BMJ Case Rep. 2015 Jan 9. 2015

- Fitzpatrick L, Healy CM, McCartan BE, Flint SR, McCreary CE, Rogers S. Patch testing for food-associated allergies in orofacial granulomatosis. J Oral Pathol Med. 2011 Jan. 40(1):10-3.

- White A, Nunes C, Escudier M, Lomer MC, Barnard K, Shirlaw P, Challacombe SJ, Sanderson JD. Improvement in orofacial granulomatosis on a cinnamon- and benzoate-free diet. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12(6):508–514. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200606000-00011

- Banks T, Gada S. A comprehensive review of current treatments for granulomatous cheilitis. Br J Dermatol. 2012 May. 166 (5):934-7.

- Campbell HE, Escudier MP, Patel P, Challacombe SJ, Sanderson JD, Lomer MC. Review article: cinnamon- and benzoate-free diet as a primary treatment for orofacial granulomatosis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011 Oct. 34 (7):687-701.

- Kemmler N, Pfannschmidt N, Strohal R. Orofacial granulomatosis as first manifestation of Crohn’s disease: successful treatment of both conditions with a combination of infliximab and dapsone. Acta Derm Venereol. 2012 Jul. 92(4):406-7.

- White A, Nunes C, Escudier M, Lomer MC, Barnard K, Shirlaw P, et al. Improvement in orofacial granulomatosis on a cinnamon- and benzoate-free diet. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006 Jun. 12 (6):508-14.

- Alves P, von Doellinger O, Quintela ML, Fonte A, Coelho R. Melkersson-Rosenthal Syndrome: A Case Report With a Psychosomatic Perspective. Adv Mind Body Med. 2017 Winter. 31 (1):14-17.

- Campbell H, Escudier MP, Brostoff J, Patel P, Milligan P, Challacombe SJ, et al. Dietary intervention for oral allergy syndrome as a treatment in orofacial granulomatosis: a new approach?. J Oral Pathol Med. 2013 Aug. 42 (7):517-22.

- Banks T, Gada S. A comprehensive review of current treatments for granulomatous cheilitis. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166(5):934–937. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2011.10794.x

- Williams PM, Greenberg MS. Management of cheilitis granulomatosa. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1991 Oct. 72(4):436-9.

- Coskun B, Saral Y, Cicek D, Akpolat N. Treatment and follow-up of persistent granulomatous cheilitis with intralesional steroid and metronidazole. J Dermatolog Treat. 2004 Sep. 15 (5):333-5.

- Gu L, Huang DY, Fu CJ, Wang ZL, Liu Y, Zhu GX. Successful treatment of cheilitis granulomatosa by intralesional injections of pingyangmycin plus dexamethasone. Eur J Dermatol. 2016 Dec 1. 26 (6):627-628.

- Kruse-Losler B, Presser D, Metze D, Joos U. Surgical treatment of persistent macrocheilia in patients with Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome and cheilitis granulomatosa. Arch Dermatol. 2005 Sep. 141(9):1085-91.

- Tan Z, Zhang Y, Chen W, Gong W, Zhao J, Xu X. Recurrent facial palsy in Melkersson Rosenthal syndrome: total facial nerve decompression is effective to prevent further recurrence. Am J Otolaryngol. 2015 May-Jun. 36 (3):334-7.

- Blinder D, Yahatom R, Taicher S. Oral manifestations of sarcoidosis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1997 Apr. 83(4):458-61.

- Girlich C, Bogenrieder T, Palitzsch KD, Schölmerich J, Lock G. Orofacial granulomatosis as initial manifestation of Crohn’s disease: a report of two cases. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002 Aug. 14(8):873-6.