Peptic ulcer disease

Peptic ulcer disease is an open sore or “ulcer” in your stomach also known as “gastric ulcer” and ulcer in your duodenum, the first part of your small intestine, called “duodenal ulcer” 1, 2, 3, 4. A person may have both gastric and duodenal ulcers at the same time. The word “peptic” means that the cause of the ulcer (an open sore) is due to pepsin (a stomach enzyme that digests proteins found in ingested food) and stomach acid (stomach acid is essentially hydrochloric acid [HCl] produced by parietal cells in the gastric glands of the stomach lining to help you digest and absorb nutrients in food). Most of the time when a gastroenterologist (a specialist in gastrointestinal diseases) is referring to a “stomach ulcer” the doctor means a peptic ulcer. Peptic ulcer disease usually occurs in your stomach (“gastric ulcer”) and proximal duodenum (“duodenal ulcer”); less commonly, it occurs in the lower esophagus, the distal duodenum, or the jejunum, as in Zollinger-Ellison syndrome, in hiatal hernias (Cameron ulcers), or in ectopic gastric mucosa (e.g., in Meckel’s diverticulum). Approximately 1 in 5 peptic ulcer disease are caused by Helicobacter pylori infection and use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin IB, others), and naproxen sodium (Aleve) 5, 6. Epigastric pain (pain in the upper central region of your abdomen) is the most common symptom of both gastric and duodenal ulcers, characterized by a gnawing or burning sensation and that occurs after meals—classically, shortly after meals with gastric ulcers and 2-3 hours afterward with duodenal ulcers 4.

You’re at risk for peptic ulcer disease if you:

- Are 50 years old or older.

- Drink alcohol in large amounts and/or often.

- Smoke cigarettes or use tobacco.

- Have a family member who has ulcer disease.

You’re at risk for nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)-caused ulcers if you:

- Are age 60 or older (your stomach lining becomes frailer with age).

- Have had past issues with ulcers and internal bleeding.

- Take steroid medications, such as prednisone.

- Take blood thinners, such as warfarin.

- Drink alcohol or use tobacco on a routine basis.

- Have certain side effects after taking NSAIDs, such as upset stomach and heartburn.

- Take NSAIDs in amounts higher than instructed on the drug facts label or by your doctor or pharmacist.

- Take many different medications that have aspirin and other NSAIDs.

- Take NSAIDs for long periods of time.

- Have had weight-loss surgery (bariatric surgery).

Many people with uncomplicated peptic ulcer disease have no symptoms at all. Some people with an peptic ulcer have stomach pain. This pain is often in the upper abdomen. Sometimes food makes the stomach pain better, and sometimes food makes it worse. Other symptoms include nausea, vomiting, or feeling bloated or full. It is important to know that there are many causes of abdominal pain, so not all pain in your abdomen is an “ulcer”. The most important symptoms that peptic ulcers cause are related to bleeding 3. Bleeding from an ulcer can be slow and go unnoticed or can cause life-threatening hemorrhage. Ulcers that bleed slowly might not produce the symptoms until the person becomes anemic. Symptoms of anemia include fatigue, shortness of breath with exercise and pale skin color.

Bleeding that occurs more rapidly might show up as melena – jet black, very sticky stool (often compared to “roof tar”) or even a large amount of dark red or maroon blood in the stool. People with bleeding ulcers may also vomit. This vomit may be red blood or may look like “coffee grounds”. Other symptoms might include “passing out” or feeling lightheaded. Symptoms of rapid bleeding represent a medical emergency. If this occurs, immediate medical attention is needed. People with these symptoms should call their local emergency services number or go to the nearest emergency room.

Researchers estimate about 1% to 6% of people in the United States have peptic ulcers 7. Approximately 500,000 people develop peptic ulcer disease in the United States each year 8. In 70 percent of patients peptic ulcer disease occurs between the ages of 25 and 64 years 9. People with gastric ulcers are also at risk of developing stomach cancer (gastric cancer).

In most people with uncomplicated peptic ulcer disease, routine laboratory tests usually are not helpful; instead, documentation of peptic ulcer disease depends on endoscopic confirmation. Testing for H.pylori infection is essential in all patients with peptic ulcers. Rapid urease tests are considered the endoscopic diagnostic test of choice. Of the noninvasive tests, fecal antigen testing is more accurate than antibody testing and is less expensive than urea breath tests but either is reasonable. A fasting serum gastrin level should be obtained in certain cases to screen for Zollinger-Ellison syndrome.

Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy also called EsophagoGastroDuodenoscopy (EGD) is the preferred diagnostic test in the evaluation of patients with suspected peptic ulcer disease. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy provides an opportunity to visualize the ulcer, to determine the presence and degree of active bleeding, and to attempt to stop the bleeding by direct measures, if required. Endoscopy is performed early in patients older than 45 to 50 years of age and in patients with associated so-called alarm symptoms of stomach cancer. Note that early-stage stomach cancer (gastric cancer) rarely causes symptoms, making it hard to detect 10, 11, 12. When they happen, symptoms might include indigestion and pain in the upper part of the belly. Symptoms might not happen until the stomach cancer is advanced. Later stages of stomach cancer might cause symptoms such as feeling very tired, losing weight without trying, vomiting blood and having black stools 10, 11, 12.

When stomach cancer does cause signs and symptoms, they can include 10, 12, 11:

- Indigestion and stomach discomfort

- A bloated feeling after eating

- Vague discomfort in the abdomen (belly), usually above the belly button

- Feeling full after eating only a small meal

- Mild nausea

- Loss of appetite or poor appetite

- Heartburn

Symptoms of advanced stomach cancer (cancer has spread beyond the stomach to other parts of the body) may include the symptoms of early-stage stomach cancer and 10, 12, 11:

- Blood in the stool

- Vomiting, with or without blood

- Weight loss for no known reason (without trying)

- Stomach pain

- Yellowing of the skin and eyes (jaundice), if the cancer spreads to the liver

- Ascites (swelling or fluid build-up in the abdomen)

- Trouble swallowing

- Feeling tired or weak, as a result of having too few red blood cells (anemia)

Most of these symptoms are more likely to be caused by things other than stomach cancer, such as a viral infection or an ulcer. It’s important to check with your doctor if you have any of these symptoms. Your doctor will ask when your symptoms started and how often you’ve been having them. If it is stomach cancer, ignoring symptoms can delay treatment and make it less effective.

Peptic ulcers will get worse if not treated. Most patients with peptic ulcer disease are treated successfully with antibiotics to kill H. pylori bacteria and/or avoidance of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), along with the appropriate use of medicines to reduce stomach acids. In the United States, the recommended primary therapy for H. pylori infection is proton pump inhibitor (PPI)–based triple therapy 13. These regimens result in a cure of infection and ulcer healing in approximately 85-90% of cases 14. Ulcers can recur in the absence of successful H. pylori eradication.

In patients with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)-associated peptic ulcers, discontinuation of NSAIDs is paramount, if it is clinically feasible. For patients who must continue with their NSAIDs, proton pump inhibitor (PPI) maintenance is recommended to prevent recurrences even after eradication of H pylori 15, 16. Preventive regimens that have been shown to dramatically reduce the risk of NSAID-induced gastric and duodenal ulcers include the use of a prostaglandin analog or a proton pump inhibitor (PPI). Maintenance therapy with medicines to reduce stomach acids (eg, H2 blockers, PPIs) for 1 year is indicated in high-risk patients.

Antacids and milk can’t heal peptic ulcers. Not smoking and avoiding alcohol can help. You may need surgery if your ulcers don’t heal. The indications for urgent surgery include failure to achieve hemostasis endoscopically, recurrent bleeding despite endoscopic attempts at achieving hemostasis (many advocate surgery after two failed endoscopic attempts), and perforation.

Figure 1. Digestive system

Footnotes: Your digestive system processes nutrients in foods that you have eaten and helps pass waste material out of your body. Food moves from your throat to your stomach through a tube called the esophagus. After food enters your stomach, it is broken down by stomach acid and muscles that mix the food and liquid with digestive juices. After leaving your stomach, partly digested food passes into your small intestine and then into your large intestine. The end of the large intestine, called the rectum, stores the waste from the digested food until it is pushed out of the anus during a bowel movement.

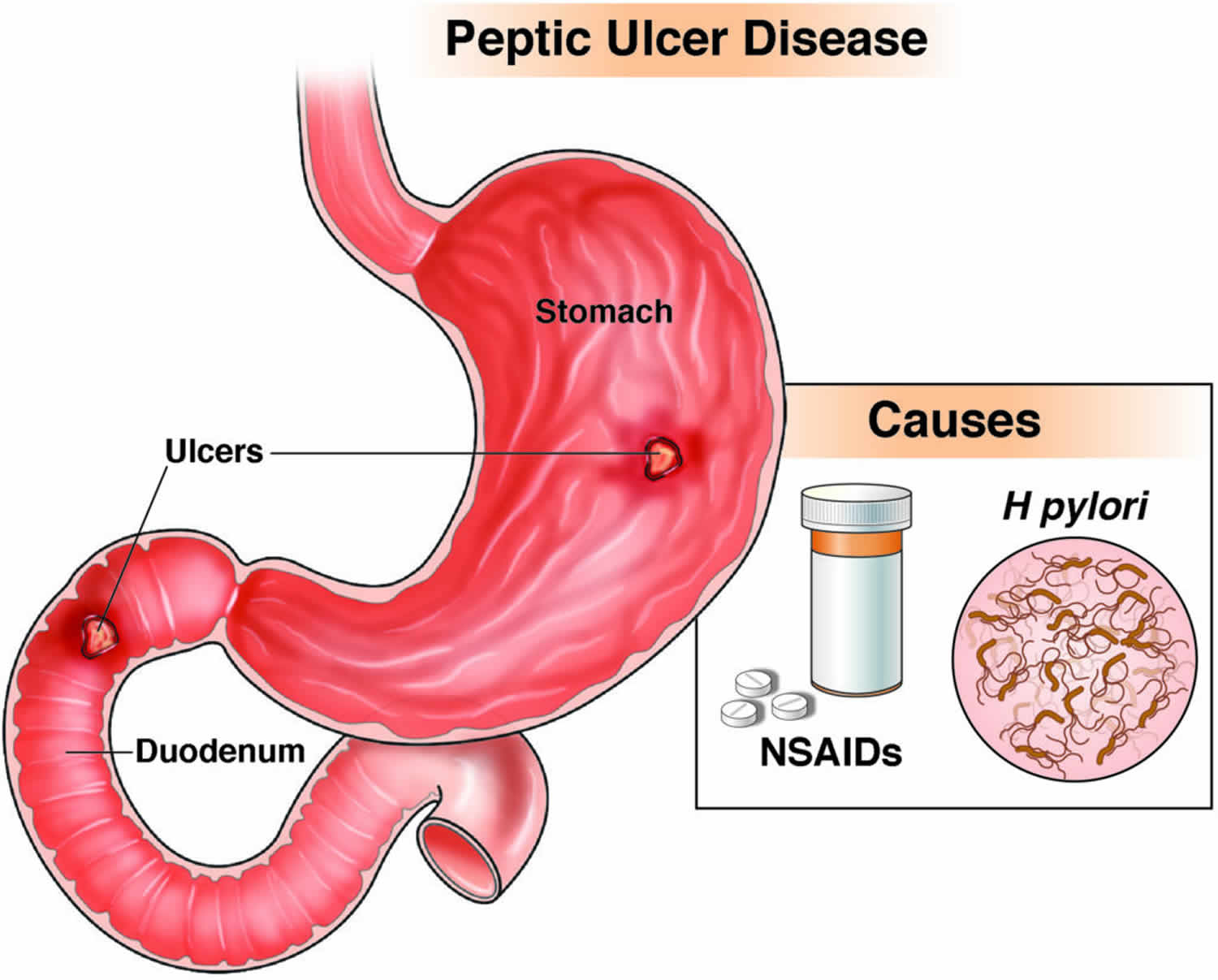

Figure 2. Peptic ulcer disease

Footnotes: Some people use the word ‘stomach’ to refer to the belly area. The medical term for this area is the abdomen. For instance, some people with pain in this area would say they have a ‘stomach ache’, when in fact the pain could be coming from some other organ in the area. Doctors would call this symptom ‘abdominal pain,’ because the stomach is only one of many organs in the abdomen.

See your doctor if you have a burning, aching pain in your upper belly that won’t go away, especially if you also have nausea, vomiting and diarrhea.

Tell your doctor if you’ve been using nonprescription medicines to reduce stomach acid. These include omeprazole (Prilosec, Zegerid), cimetidine (Tagamet HB) or famotidine (Pepcid AC). These medicines may mask your symptoms, which could delay your diagnosis.

Who is more likely to develop peptic ulcers?

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection and taking non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs) are the two most common causes of peptic ulcers.

People are more likely to develop peptic ulcers if they are:

- infected with the bacteria Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori)

- taking nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as aspirin, ibuprofen, and naproxen

People also are more likely to develop peptic ulcers if they:

- are older adults

- had a peptic ulcer before

- smoke

Can changes to my diet help prevent or treat a peptic ulcer?

Researchers have not found that diet and nutrition play an important role in causing, preventing, or treating peptic ulcers. Doctors do not recommend following a special diet or avoiding specific foods or drinks to prevent or treat ulcers.

If you smoke, quitting smoking can lower your risk for developing ulcers and help existing ulcers heal.

Peptic ulcer disease causes

The two most important causes of peptic ulcer disease are infection with Helicobacter pylori and a group of medications known as Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs). Other causes of peptic ulcers are uncommon or rare. In rare cases, doctors can’t find the cause of peptic ulcers. Doctors may call ulcers with unknown causes idiopathic peptic ulcers.

Less common causes of peptic ulcers include:

- infections caused by certain viruses, fungi, or bacteria other than H. pylori

- medicines that increase the risk of developing ulcers, including corticosteroids, medicines used to treat low bone mass, and some antidepressants, especially when you take these medicines with NSAIDs

- surgery or medical procedures that affect the stomach or duodenum

Less common causes of peptic ulcers also include certain diseases and health conditions, such as:

- diseases that can affect the stomach, such as cancer or Crohn’s disease

- injury, blockage, or lack of blood flow that affects the stomach or duodenum

- life-threatening health conditions that require critical care

- severe chronic diseases, such as cirrhosis or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- Zollinger-Ellison syndrome, a condition that occurs when one or more tumors called gastrinomas cause your stomach to make too much acid.

Helicobacter pylori also called “H. pylori” is a bacterium that lives in the mucous layer that covers and protects tissues that line the stomach and small intestine. The understanding that H. pylori can cause ulcers was one of the most important medical discoveries of the late 20th century. In fact, Dr. Barry Marshall and Dr. J. Robin Warren were awarded the 2005 Nobel Prize in Medicine for this discovery.

Often, the H. pylori bacterium causes no problems, but it can cause inflammation of the stomach’s inner layer, producing an ulcer. People infected with H. pylori are at increased risk of developing peptic ulcers. When a person is diagnosed with an ulcer, testing for H. pylori is often done. There are a number of tests to diagnose H. pylori and the type of test used depends on your situation.

It’s not clear how H. pylori infection spreads. It may be transmitted from person to person by close contact with an infected person’s vomit, stool, or saliva. Food or water contaminated with an infected person’s vomit, stool, or saliva may also spread the bacteria from person to person.

People with ulcers who are infected with H. pylori should have their infection treated. Treatment usually consists of taking either three or four drugs. The drug therapy will use acid suppression therapy with a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) along with antibiotic therapy and perhaps a bismuth containing agent such as Pepto-Bismol. H. pylori can be very difficult to cure; so it is very important that people being treated for this infection take their entire course of antibiotics as prescribed.

Taking aspirin, as well as certain over-the-counter and prescription pain medications called nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), can irritate or inflame the lining of your stomach and small intestine. There are many drugs in this group. A few of these include ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin IB, others), naproxen sodium (Aleve, Anaprox DS, Naprosyn, others), ketoprofen, ketorolac (Toradol), oxaprozin (Daypro) and others. NSAIDs are also included in some combination medications, such as Alka-Seltzer, Goody’s Powder and BC Powder.

In addition, taking certain other medications along with NSAIDs, such as steroids, anticoagulants, low-dose aspirin, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), alendronate (Fosamax) and risedronate (Actonel), can greatly increase the chance of developing ulcers.

Acetaminophen (Tylenol, Paracetamol) is NOT a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) and is therefore the preferred non-prescription treatment for pain in patients at risk for peptic ulcer disease.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) use are very common because many are available over the counter (OTC) without a doctor’s prescription and therefore they are a very common cause of peptic ulcers. NSAIDs cause ulcers by interrupting the natural ability of the stomach and the duodenum to protect themselves from stomach acid. NSAIDs also can interfere with blood clotting, which has obvious importance when ulcers bleed.

People who take NSAIDs for a long time and/or at high doses, have a higher risk of developing ulcers. These people should discuss the various options for preventing ulcers with their physician. Some people are given an acid suppressing proton pump inhibitor (PPI). These drugs can prevent or significantly reduce the risk of an ulcer being caused by NSAIDs.

There are many myths about peptic ulcers. Ulcers are not caused by emotional “stress” or by worrying. They are not caused by spicy foods or a rich diet. Certain foods might irritate an ulcer that is already there, however, the food is not the cause of the ulcer. People diagnosed with ulcers do not need to follow a specific diet. The days of ulcer patients surviving on a bland diet are a thing of the past.

Risk factors for developing peptic ulcer

In addition to having risks related to taking nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), you may have an increased risk of peptic ulcers if you:

- Smoke. Smoking may increase the risk of peptic ulcers in people who are infected with H. pylori.

- Drink alcohol. Alcohol can irritate and erode the mucous lining of your stomach, and it increases the amount of stomach acid that’s produced.

- Have untreated stress.

- Eat spicy foods.

Alone, these factors do not cause ulcers, but they can make ulcers worse and more difficult to heal.

Peptic ulcer disease pathophysiology

Peptic ulcer disease results from an imbalance between gastric mucosal protective and destructive factors. Under normal conditions, a physiologic balance exists between gastric acid secretion and gastroduodenal mucosal defense 17. Mucosal injury and, thus, peptic ulcer occurs when the balance between the gastric mucosal protective and destructive factors is disrupted. Destructive factors, such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), H pylori infection, alcohol, bile salts, acid, and pepsin, can alter the mucosal defense by allowing the back diffusion of hydrogen ions and subsequent epithelial cell injury 17. The defensive mechanisms include tight intercellular junctions, mucus, bicarbonate, mucosal blood flow, cellular restitution, and epithelial renewal 17.

Risk factors predisposing to the development of peptic ulcer disease 1:

- Helicobacter pylori infection

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) use

- First-degree relative with peptic ulcer disease

- Emigrant from a developed nation

- African American/Hispanic ethnicity

H. pylori infection and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) use account for most cases of peptic ulcer disease. The rate of H.pylori infection for duodenal ulcers in the United States is less than 75% for patients who do not use NSAIDs 17. Excluding patients who used NSAIDs, 61% of duodenal ulcers and 63% of gastric ulcers were positive for H.pylori in one study 17. These rates were lower in whites than in nonwhites. Prevalence of H.pylori infection in complicated ulcers (i.e., bleeding, perforation) is significantly lower than that found in uncomplicated ulcer disease. H. pylori is known to colonize the gastric mucosa and causes inflammation. The H. pylori also impairs the secretion of bicarbonate, promoting the development of acidity and gastric metaplasia.

With peptic ulcers, there is usually a defect in the mucosa that extends to the muscularis mucosa. Once the protective superficial mucosal layer is damaged, the inner layers are susceptible to acidity. Furthermore, the ability of the mucosal cells to secrete bicarbonate is compromised.

Peptic ulcer prevention

You may reduce your risk of peptic ulcer if you follow the same strategies recommended as home remedies to treat ulcers. It also may be helpful to:

- Protect yourself from H.pylori infections. It’s not clear just how H. pylori spreads, but there’s some evidence that it could be transmitted from person to person or through food and water. You can take steps to protect yourself from infections, such as H. pylori, by frequently washing your hands with soap and water and by eating foods that have been cooked completely.

- Use caution with pain relievers. If you regularly use pain relievers that increase your risk of peptic ulcer, take steps to reduce your risk of stomach problems. For instance, take your medication with meals. Work with your doctor to find the lowest dose possible that still gives you pain relief. Avoid drinking alcohol when taking your medication, since the two can combine to increase your risk of stomach upset. If you need an nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID), you may need to also take additional medications such as an antacid, a proton pump inhibitor, an acid blocker or cytoprotective agent. A class of NSAIDs called COX-2 inhibitors (e.g., celecoxib) may be less likely to cause peptic ulcers, but may increase your risk of heart attack.

Peptic ulcer disease signs and symptoms

Many people with peptic ulcers don’t even have symptoms. The most common symptom of an peptic ulcer is a burning pain in your stomach between your breastbone and your belly button. You may often feel this pain when your stomach is empty (often between meals), but it can happen at any time even during the night. The burning stomach pain could last from a few minutes to many hours and may sometimes wake you in the middle of the night. The burning stomach pain is often reduced by eating certain foods that buffer stomach acid, fluids or taking antacids, but then it may come back.

While not as common as burning stomach pain, other symptoms could be:

- Upset stomach

- Vomiting

- Vomiting blood, which may appear red or black

- Blood in the stool (stools that are black or tarry)

- Loss of appetite

- Trouble breathing

- Feeling faint

- Nausea or vomiting

- Unexplained weight loss

- Appetite changes

- Anemia (low iron in your blood, which can make you feel weak and tired), when an ulcer bleeds without being treated.

See your doctor if you have the severe signs or symptoms listed above. Also see your doctor if over-the-counter antacids and acid blockers relieve your pain but the pain returns.

Peptic ulcer complications

Left untreated, peptic ulcers can result in:

- Internal bleeding. Bleeding can occur as slow blood loss that leads to anemia or as severe blood loss that may require hospitalization or a blood transfusion. Severe blood loss may cause black or bloody vomit or black or bloody stools.

- A hole (perforation) in your stomach wall. Peptic ulcers can eat a hole through (perforate) the wall of your stomach or small intestine, putting you at risk of serious infection of your abdominal cavity (peritonitis).

- Stomach outlet obstruction. Peptic ulcers can block passage of food through the digestive tract, causing you to become full easily, to vomit and to lose weight either through swelling from inflammation or through scarring.

- Stomach cancer. Studies have shown that people infected with H. pylori have an increased risk of stomach cancer.

Peptic ulcer disease diagnosis

To detect an peptic ulcer, your doctor may first take a medical history and perform a physical exam. You then may need to undergo diagnostic tests, such as:

- Laboratory tests for H. pylori. Your doctor may recommend tests to determine whether the bacterium H. pylori is present in your body. He or she may look for H. pylori using a blood, stool or breath test. The breath test is the most accurate.

- Urea breath test. Doctors may use a urea breath test to check for H. pylori infection. For the breath test, you will swallow a capsule, liquid, or pudding that contains urea “labeled” with a special carbon atom (radioactive carbon). H. pylori breaks down the substance in your stomach. If H. pylori is present, the bacteria will convert the urea into carbon dioxide. After a few minutes, you will breathe into a bag, exhaling carbon dioxide, which is then sealed. If you’re infected with H. pylori, your breath sample will contain the radioactive carbon in the form of carbon dioxide (CO2). If you are taking an antacid prior to the testing for H. pylori, make sure to let your doctor know. Depending on which test is used, you may need to discontinue the medication for a period of time because antacids can lead to false-negative results.

- Blood test. Doctors may use blood tests to check for signs of H. pylori infection or complications of peptic ulcers. For a blood test, a health care professional will take a blood sample from you and send the sample to a lab.

- Stool test. Doctors may use stool tests to check for H. pylori infection. Your doctor will give you a container for catching and holding a stool sample. You will receive instructions on where to send or take the kit for testing.

- Upper gastrointestinal endoscopyy also called EsophagoGastroDuodenoscopy (EGD). Your doctor is more likely to recommend endoscopy if you are older, have signs of bleeding, or have experienced recent weight loss or difficulty eating and swallowing. Your doctor may use a scope to examine your upper digestive system (endoscopy). During upper endoscopy (EGD), your doctor passes a hollow tube equipped with a lens (endoscope) down your throat and into your esophagus, stomach and small intestine. Using the endoscope, your doctor looks for ulcers. If your doctor detects an ulcer, a small tissue sample (biopsy) may be removed for examination in a lab. A biopsy can also identify whether H. pylori is in your stomach lining. If the endoscopy shows an ulcer in your stomach, a follow-up endoscopy should be performed after treatment to show that it has healed, even if your symptoms improve.

- Upper gastrointestinal (GI) series. Sometimes called a barium swallow, this series of X-rays of your upper digestive system creates images of your esophagus, stomach and small intestine. During the X-ray, you swallow a white liquid (containing barium) that coats your digestive tract and makes an ulcer more visible.

Today, the preferred method for diagnosing peptic ulcers is with an upper endoscopy (EGD) given the flexible camera is better able to detect even small ulcers and because it allows for potential treatment at that time if the ulcer is bleeding. An upper gastrointestinal series (barium swallow) can miss small ulcers and also does not allow direct treatment of an ulcer.

When someone has an ulcer that has bled significantly, treatment might be done at the time of upper endoscopy (EGD). There are a number of techniques that can be performed during an esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) to control bleeding from an ulcer. The gastroenterologist might inject medications, use a catheter to cauterize the ulcer (burn a bleeding vessel shut) or place a small clip to clamp off a bleeding vessel. Not all ulcers need to be treated this way. The doctor doing the EGD will decide if treatment is indicated based on the way the ulcer looks. The doctor will usually treat an ulcer that is actually bleeding when it is seen and will also often treat other ulcers if they have a certain appearance. These findings are sometimes called “stigmata of recent hemorrhage” or just “stigmata”. Stigmata will usually get treated during the EGD if they are classified as high-risk. Common high-risk findings include a “visible vessel” and an “adherent clot”.

Peptic ulcer disease treatment

Treatment for peptic ulcers depends on the cause. Usually treatment will involve killing the H. pylori bacteria if present, eliminating or reducing use of NSAIDs if possible, and helping your ulcer to heal with medication.

Medications can include:

- Antibiotic medications to kill H. pylori. If H. pylori is found in your digestive tract, your doctor may recommend a combination of antibiotics to kill the bacterium. These may include amoxicillin (Amoxil), clarithromycin (Biaxin), metronidazole (Flagyl), tinidazole (Tindamax), tetracycline and levofloxacin. The antibiotics used will be determined by where you live and current antibiotic resistance rates. You’ll likely need to take antibiotics for two weeks, as well as additional medications to reduce stomach acid, including a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) and possibly bismuth subsalicylate (Pepto-Bismol). To find out if the antibiotics worked, your doctor may recommend testing you for H. pylori at least 4 weeks after you’ve finished taking the antibiotics 18. If you still have an H. pylori infection, your doctor may prescribe a different combination of antibiotics and other medicines to treat the infection. Making sure that all of the H. pylori bacteria have been killed is important.

- Medications that block acid production and promote healing. Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) reduce stomach acid by blocking the action of the parts of cells that produce acid. These drugs include the prescription and over-the-counter medications omeprazole (Prilosec, Zegerid), lansoprazole (Prevacid), rabeprazole (Aciphex), esomeprazole (Nexium), dexlansoprazole (Dexilant) and pantoprazole (Protonix). There are very few medical differences between these drugs. However, long-term use of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), particularly at high doses, may increase your risk of hip, wrist and spine fracture. Ask your doctor whether a calcium supplement may reduce this risk.

- Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) require a meal to activate them. You should eat a meal within 30 minutes to 1 hour after taking this medication for the acid suppression therapy to work most effectively. Waiting later than this time can decrease the positive effect of this medication. This might delay healing or even result in the failure of the ulcer to heal.

- Medications to reduce acid production. Acid blockers also called histamine (H-2) blockers reduce the amount of stomach acid released into your digestive tract, which relieves ulcer pain and encourages healing. Available by prescription or over the counter, acid blockers include the medications famotidine (Pepcid AC), cimetidine (Tagamet HB) and nizatidine (Axid AR).

- Antacids that neutralize stomach acid. Your doctor may include an antacid in your drug regimen. Antacids neutralize existing stomach acid and can provide rapid pain relief. Side effects can include constipation or diarrhea, depending on the main ingredients. Antacids can provide symptom relief but generally aren’t used to heal your ulcer.

- Medications that protect the lining of your stomach and small intestine. In some cases, your doctor may prescribe medications called cytoprotective agents that help protect the tissues that line your stomach and small intestine. Options include the prescription medications sucralfate (Carafate) and misoprostol (Cytotec).

Follow-up after initial treatment

Treatment for peptic ulcers is often successful, leading to ulcer healing. But if your symptoms are severe or if they continue despite treatment, your doctor may recommend endoscopy to rule out other possible causes for your symptoms. If an ulcer is detected during endoscopy, your doctor may recommend another endoscopy after your treatment to make sure your ulcer has healed. Ask your doctor whether you should undergo follow-up tests after your treatment.

People with gastric ulcers (only in the stomach) usually have another upper endoscopy (EGD) several weeks after treatment to make sure that the ulcer is gone. This is because a very small number of gastric ulcers might contain cancer. Duodenal ulcers (at the beginning of the small intestine) usually don’t need to be looked at again.

Peptic ulcers that fail to heal (refractory peptic ulcers)

Peptic ulcers that don’t heal with treatment are called refractory peptic ulcers. There are many reasons why an ulcer may fail to heal, including:

- Not taking medications according to directions

- The fact that some types of H. pylori are resistant to antibiotics

- Regular use of tobacco

- Regular use of pain relievers — such as NSAIDs — that increase the risk of ulcers

Less often, refractory ulcers may be a result of:

- Extreme overproduction of stomach acid, such as occurs in Zollinger-Ellison syndrome

- An infection other than H. pylori

- Stomach cancer

- Other diseases that may cause ulcerlike sores in the stomach and small intestine, such as Crohn’s disease

Treatment for refractory ulcers generally involves eliminating factors that may interfere with healing, along with using different antibiotics.

If your ulcer doesn’t heal or comes back after treatment, your doctor may:

- check for and treat any factors that could be causing the ulcer, such as an H. pylori infection.

- recommend you quit smoking, if you smoke. Smoking can slow ulcer healing.

- recommend or prescribe more medicines to help heal the ulcer.

- recommend an upper GI endoscopy to obtain biopsies.

In rare cases, doctors may recommend surgery to treat peptic ulcers that don’t heal.

If you have a serious complication from an peptic ulcer, such as acute bleeding or a perforation, you may require surgery. However, surgery is needed far less often now than previously because of the many effective medications available.

Peptic ulcer disease prognosis

The prognosis of peptic ulcer disease is excellent when the underlying cause of peptic ulcer disease cause is successfully treated. Most patients are treated successfully with the eradication of H.pylori infection, avoidance of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents (NSAIDs), and the appropriate use of medicines to reduce stomach acids (eg, H2 blockers, PPIs). Eradication of H.pylori infection changes the natural history of peptic ulcer disease, with a decrease in the ulcer recurrence rate from 60% to 90% to approximately 10% to 20% 19. Recurrence of the ulcer may be prevented by maintaining good hygiene and avoiding alcohol, smoking, and NSAIDs. Unfortunately, recurrence is common with rates exceeding 60% in most series 1. The higher recurrence rate suggested an increased number of peptic ulcers not caused by H.pylori infection 19.

With regard to NSAID-related peptic ulcers, NSAID-induced gastric perforation occurs at a rate of 0.3% per patient per year and the incidence of obstruction is approximately 0.1% per patient year 1. Combining both duodenal ulcers and gastric ulcers, the rate of any complication in all age groups combined is approximately 1-2% per ulcer per year.

The mortality rate for peptic ulcer disease, which has decreased modestly in the last few decades, is approximately 1 death per 100,000 cases. If one considers all patients with duodenal ulcers, the mortality rate due to ulcer hemorrhage is approximately 5% 20. Over the last 20 years, the mortality rate in the setting of ulcer hemorrhage has not changed appreciably despite the advent of histamine-2 receptor antagonists (H2 blockers) and proton pump inhibitors (PPIs). However, evidence from meta-analyses and other studies has shown a decreased mortality rate from bleeding peptic ulcers when intravenous PPIs are used after successful endoscopic therapy 21, 22, 23, 24.

Emergency operations for peptic ulcer perforation carry a mortality risk of 6-30% 25, 26. Factors associated with higher mortality in this setting include the following:

- Shock at the time of admission

- Renal insufficiency

- Delaying the initiation of surgery for more than 12 hours after presentation

- Concurrent medical illness (eg, cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus)

- Age older than 70 years

- Cirrhosis

- Immunocompromised state

- Location of ulcer (mortality associated with perforated gastric ulcer is twice that associated with perforated duodenal ulcer)

In a retrospective population-based study (2001-2014) that evaluated long-term mortality in 234 patients who underwent surgery for perforated peptic ulcer, mortality was 15.2% at 30 days, 19.2% at 90 days, 22.6% at 1 year, and 24.8% at 2 years 27. When the 30-day mortality data were excluded, 36% of patients died during a median follow-up of 57 months. Independent factors associated with an increased risk of long-term mortality included age older than 60 years and the presence of comorbidities such as active malignancy, hypoalbuminemia, pulmonary disease, cardiovascular disease, and severe postoperative complications during the initial stay 27.

- Malik TF, Gnanapandithan K, Singh K. Peptic Ulcer Disease. [Updated 2023 Jun 5]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK534792[↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Peptic Ulcers (Stomach or Duodenal Ulcers). https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/digestive-diseases/peptic-ulcers-stomach-ulcers/all-content[↩]

- Peptic Ulcer Disease Overview. https://gi.org/topics/peptic-ulcer-disease/[↩][↩]

- Peptic Ulcer Disease. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/181753-overview[↩][↩]

- Fashner J, Gitu AC. Diagnosis and Treatment of Peptic Ulcer Disease and H. pylori Infection. Am Fam Physician. 2015 Feb 15;91(4):236-42. https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2015/0215/p236.html[↩]

- McConaghy JR, Decker A, Nair S. Peptic Ulcer Disease and H. pylori Infection: Common Questions and Answers. Am Fam Physician. 2023 Feb;107(2):165-172. https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2023/0200/peptic-ulcer-disease-h-pylori-infection.html[↩]

- Ingram RJM, Ragunath K, Atherton JC. Chapter 56: Peptic ulcer disease. In: Podolsky DK, Camilleri M, Fitz G, et al, eds. Yamada’s Textbook of Gastroenterology. 6th ed. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2016:1032–1077.[↩]

- University of Michigan Health System. Peptic ulcer disease. https://www.cme.med.umich.edu/pdf/guideline/PUD05.pdf[↩]

- Sonnenberg A, Everhart JE. The prevalence of self-reported peptic ulcer in the United States. Am J Public Health. 1996 Feb;86(2):200-5. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.2.200[↩]

- Signs and Symptoms of Stomach Cancer. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/stomach-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging/signs-symptoms.html[↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Stomach Cancer Symptoms. https://www.cancer.gov/types/stomach/symptoms[↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Stomach cancer. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/stomach-cancer/symptoms-causes/syc-20352438[↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Chey WD, Wong BC; Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. American College of Gastroenterology guideline on the management of Helicobacter pylori infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007 Aug;102(8):1808-25. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01393.x[↩]

- Javid G, Zargar SA, U-Saif R, Khan BA, Yatoo GN, Shah AH, Gulzar GM, Sodhi JS, Khan MA. Comparison of p.o. or i.v. proton pump inhibitors on 72-h intragastric pH in bleeding peptic ulcer. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009 Jul;24(7):1236-43. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2009.05900.x[↩]

- Lai KC, Lam SK, Chu KM, Wong BC, Hui WM, Hu WH, Lau GK, Wong WM, Yuen MF, Chan AO, Lai CL, Wong J. Lansoprazole for the prevention of recurrences of ulcer complications from long-term low-dose aspirin use. N Engl J Med. 2002 Jun 27;346(26):2033-8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012877[↩]

- Lai KC, Lam SK, Chu KM, Hui WM, Kwok KF, Wong BC, Hu HC, Wong WM, Chan OO, Chan CK. Lansoprazole reduces ulcer relapse after eradication of Helicobacter pylori in nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug users–a randomized trial. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003 Oct 15;18(8):829-36. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01762.x[↩]

- Peptic Ulcer Disease Pathophysiology. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/181753-overview#a2[↩][↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Vakil NB. Peptic ulcer disease: treatment and secondary prevention. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/peptic-ulcer-disease-treatment-and-secondary-prevention[↩]

- Peptic Ulcer Disease Prognosis. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/181753-overview#a8[↩][↩]

- Peptic ulcer. https://www.omicsonline.org/united-states/peptic-ulcer-peer-reviewed-pdf-ppt-articles/[↩]

- Leontiadis GI, Sreedharan A, Dorward S, Barton P, Delaney B, Howden CW, Orhewere M, Gisbert J, Sharma VK, Rostom A, Moayyedi P, Forman D. Systematic reviews of the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of proton pump inhibitors in acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Health Technol Assess. 2007 Dec;11(51):iii-iv, 1-164. doi: 10.3310/hta11510[↩]

- Bardou M, Toubouti Y, Benhaberou-Brun D, Rahme E, Barkun AN. High dose proton pump inhibition decrease both re-bleeding and mortality in high-risk patients with acute peptic ulcer bleeding [abstract]. Gastroenterology. 2003. 123(suppl 1):A625.[↩]

- Bardou M, Youssef M, Toubouti Y, et al. Newer endoscopic therapies decrease both re-bleeding and mortality in high risk patients with acute peptic ulcer bleeding: a series of meta-analyses [abstract]. Gastroenterology. 2003. 123:A239.[↩]

- Gisbert JP, Pajares R, Pajares JM. Evolution of Helicobacter pylori therapy from a meta-analytical perspective. Helicobacter. 2007 Nov;12 Suppl 2:50-8. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2007.00576.x[↩]

- Svanes C, Lie RT, Svanes K, Lie SA, Søreide O. Adverse effects of delayed treatment for perforated peptic ulcer. Ann Surg. 1994 Aug;220(2):168-75. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199408000-00008[↩]

- Sengupta TK, Prakash G, Ray S, Kar M. Surgical Management of Peptic Perforation in a Tertiary Care Center: A Retrospective Study. Niger Med J. 2020 Nov-Dec;61(6):328-333. doi: 10.4103/nmj.NMJ_191_20[↩]

- Thorsen K, Søreide JA, Søreide K. Long-Term Mortality in Patients Operated for Perforated Peptic Ulcer: Factors Limiting Longevity are Dominated by Older Age, Comorbidity Burden and Severe Postoperative Complications. World J Surg. 2017 Feb;41(2):410-418. doi: 10.1007/s00268-016-3747-z[↩][↩]