Abdominal aortic aneurysm

Abdominal aortic aneurysm also known as AAA, is a focal bulging (ballooning or widening) of the abdominal aorta that are 50% greater than the proximal normal segment or >3 cm in maximum diameter, measured by ultrasonography or computed tomography angiography (CTA) 1, 2. An abdominal aortic aneurysm is a life-threatening condition that requires monitoring or treatment depending upon the size of the aneurysm and/or symptoms 3. The aorta is the main blood vessel that carries oxygen-rich blood from your heart to your abdomen, pelvis, and legs. The abdominal aorta provides oxygen-rich blood to the tissues and organs of the abdomen and lower limbs. Your abdominal aorta is usually about 2 cm wide or about the width of a garden hose. Abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) occurs when atherosclerosis or plaque buildup causes the walls of the abdominal aorta to become weak and bulge outward like a balloon. An AAA develops slowly over time and has few noticeable symptoms. The larger an aortic aneurysm grows, the more likely it will burst or rupture, causing intense abdominal or back pain, dizziness, nausea or shortness of breath and cause dangerous bleeding or even death.

In the United States, the estimated abdominal aortic aneurysm prevalence is 1.4% among people between 50 and 84 years of age or 1.1 million adults 4, 5; abdominal aortic aneurysm prevalence is lower among women than among men and lower among Black and Asian persons than among White persons 4, 6. A 2013 meta-analysis analyzing 56 studies of the years 1991–2013 found abdominal aortic aneurysm prevalence rates of 6.0% for men and 1.6% for women 7. Every year, 200,000 people in the U.S. are diagnosed with an abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) 8. A ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm is the 15th leading cause of death in the country, and the 10th leading cause of death in men older than 55. Furthermore, among abdominal aortic aneurysm patients, women are more likely to die from an abdominal aortic aneurysm-related death (i.e., rupture), while men die from cancer more often than from ruptures 9. The mean time between a scan with no detected aortic abnormalities and abdominal aortic aneurysm-related death is about 10 years (range 3.8–15.0) 10.

Abdominal aortic aneurysm predisposing factors include advanced age, family history, previous or current tobacco use, hypercholesterolemia, and hypertension 11.

Several things can play a role in the development of an abdominal aortic aneurysm, including:

- Hardening of the arteries (atherosclerosis). Atherosclerosis occurs when fat and other substances build up on the lining of a blood vessel.

- High blood pressure. High blood pressure can damage and weaken the aorta’s walls.

- Blood vessel diseases. These are diseases that cause blood vessels to become inflamed.

- Infection in the aorta. Rarely, a bacterial or fungal infection might cause an abdominal aortic aneurysms.

- Trauma. For example, being injured in a car accident can cause an abdominal aortic aneurysms.

- Family history. Aneurysms run in families. If a first-degree relative has had an AAA, you are 12 times more likely to develop an abdominal aortic aneurysm. Of patients in treatment to repair an abdominal aortic aneurysm, 15–25% have a first-degree relative with the same type of aneurysm.

Some people are at high risk for aneurysms. It is important for them to get abdominal aortic aneurysm screening, because aneurysms can develop and become large before causing any symptoms. Abdominal aortic aneurysms are common and affect approximately 7.5% of patients aged over 65 years 12. Abdominal aortic aneurysm screening is recommended for people between the ages of 65 and 75 if they have a family history, or if they are men who have smoked.

Doctors use imaging tests to find aneurysms. Most abdominal aortic aneurysms are found during tests done for other reasons. Your doctor can confirm the presence of an AAA with an abdominal ultrasound, abdominal and pelvic CT or angiography. With the increased use of ultrasound, the diagnosis of abdominal aortic aneurysms is quite common. They tend to be more common in smokers and elderly white males 3. Although autopsy studies may under-represent the incidence of AAA, one study from Malmo Sweden found a prevalence of 4.3% in men and 2.1% in women detected on ultrasound 13.

If you have an AAA, it is important to get regular medical care, because a large aneurysm can burst and cause internal bleeding. Listen to your doctor and follow your treatment plan. He or she may advise you to avoid lifting heavy objects. Try to avoid highly emotional situations or crises that could raise your blood pressure. Take care of yourself to prevent the aortic aneurysm from bursting or tearing.

Abdominal aortic aneurysm treatment depends on the aneurysm’s location and size as well as your age, kidney function and other conditions, but the size of the aneurysm is important, as risk of rupture increases with aneurysm size 14. The goal of abdominal aortic aneurysm treatment is to prevent an aneurysm from rupturing. Treatment may involve careful monitoring or surgery. Which treatment you have depends on the size of the aortic aneurysm and how fast it’s growing.

Large asymptomatic abdominal aortic aneurysms (greater than 5.5 cm in diameter) or those that are quickly growing or leaking may require open or endovascular surgery; patients with small abdominal aortic aneurysms measuring 3.0 to 3.9 cm in diameter should be followed with imaging surveillance in the form of duplex ultrasonography every 3 years, whereas those with aneurysms measuring 4.0 to 4.9 cm in diameter should be followed once a year and those with aneurysms that are 5.0 cm in diameter or larger should be followed every 6 months 15, 14.

Smoking cessation is recommended to reduce the risk of growth and rupture. Statins, beta-blockers, and other antihypertensive medications may be indicated to reduce cardiovascular risk, but they have not been shown to reduce growth and should not be prescribed for that purpose.

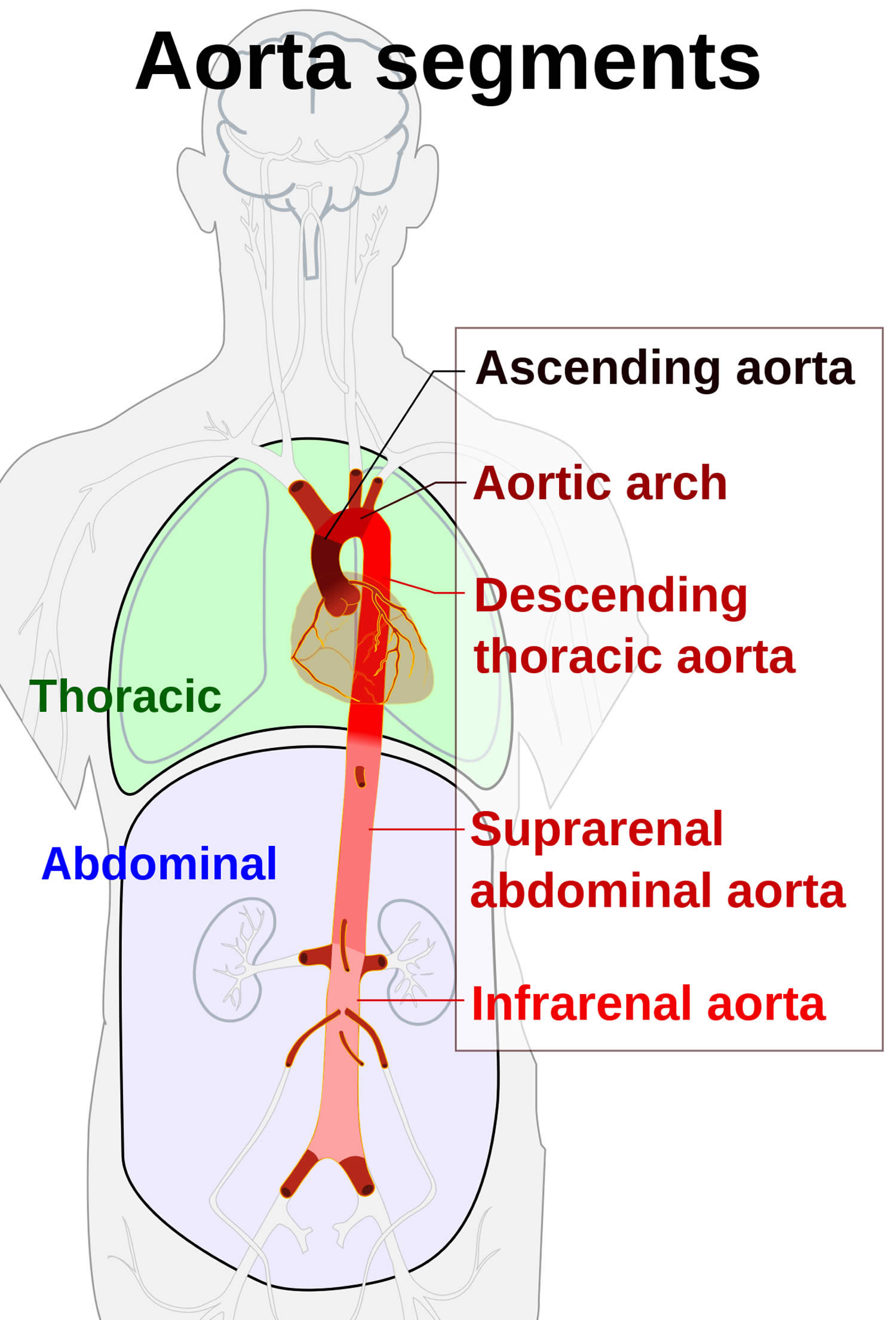

Abdominal aorta

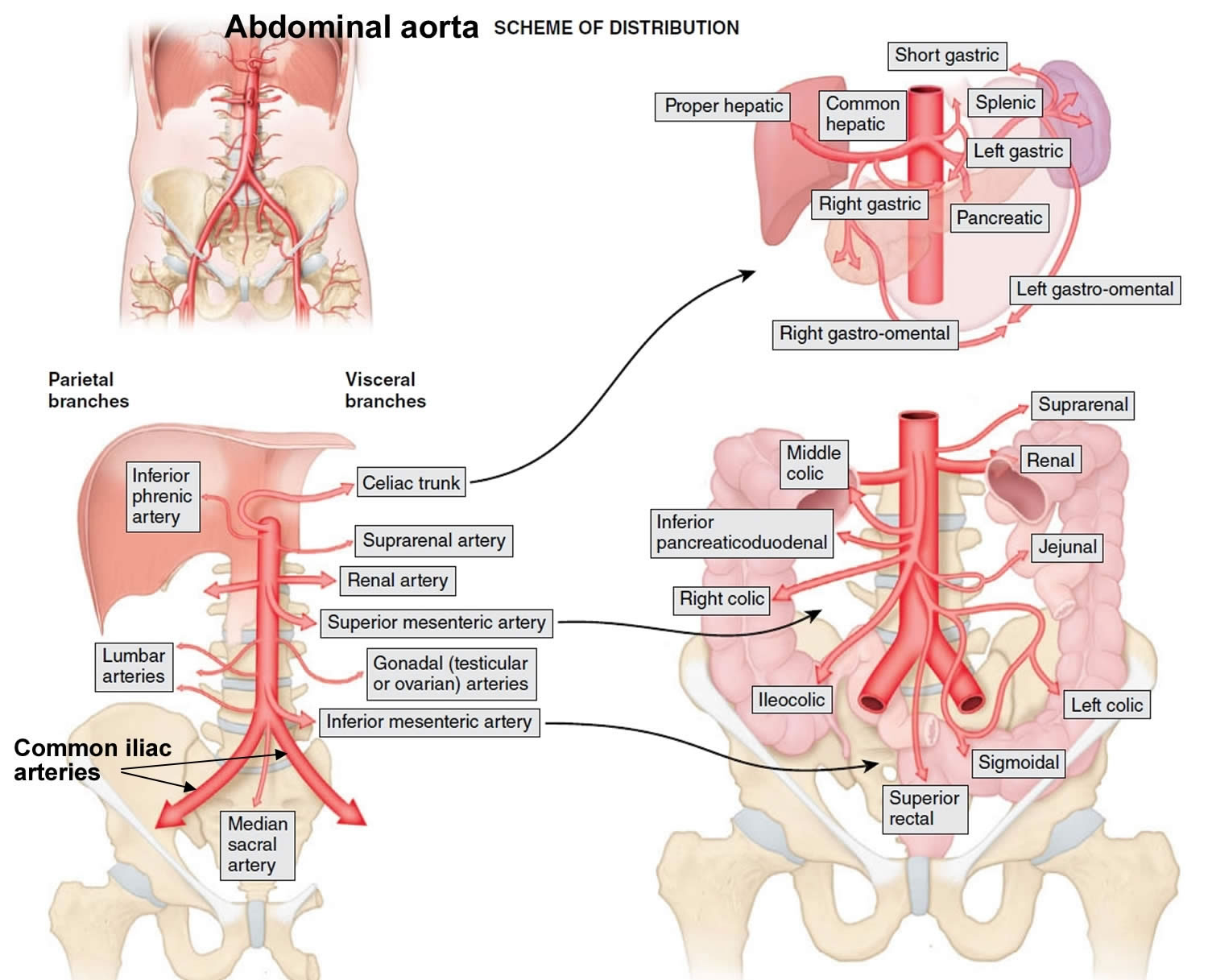

Abdominal aorta is the main blood vessel in the abdominal cavity that transmits oxygenated blood from the thoracic cavity to the organs within the abdomen and to the lower limbs. Abdominal aorta is a continuation of descending thoracic aorta at the twelfth thoracic vertebra (T12) after it passes through the diaphragm. Abdominal aorta begins at the aortic hiatus in the diaphragm and ends at about the level of the fourth lumbar vertebra (L4), where it divides into the right and left common iliac arteries. The abdominal aorta lies anterior to the vertebral column. As with the thoracic aorta, the abdominal aorta gives off visceral and parietal branches. The unpaired visceral branches arise from the anterior surface of the aorta and include the celiac trunk and the superior mesenteric and inferior mesenteric arteries. The paired visceral branches arise from the lateral surfaces of the aorta and include the suprarenal, renal, and gonadal arteries. The lone unpaired parietal branch is the median sacral artery. The paired parietal branches arise from the posterolateral surfaces of the aorta and include the inferior phrenic and lumbar arteries.

- Abdominal aorta origin: continuation of descending thoracic aorta at the twelfth thoracic vertebra (T12)

- Abdominal aorta course: descends anterior and slightly to the left of the lumbar vertebral bodies

- Abdominal aorta branches (unpaired)

- Celiac trunk (T12) is a short artery, barely more than 1 cm long, is a median branch of the abdominal aorta just below the diaphragm. It immediately gives rise to three branches—the common hepatic, left gastric, and splenic arteries.

- Superior mesenteric artery (L1) supplies small intestine and superior part of large intestine

- Inferior mesenteric artery (L3) supplies inferior part of large intestine

- Median sacral artery arises from posterior surface of abdominal aorta about 1 cm superior to bifurcation (division into two branches) of aorta into right and left common iliac arteries. Median sacral artery supplies sacrum, coccyx, sacral spinal nerves, and piriformis muscle.

- Abdominal aorta branches (paired)

- Middle adrenal arteries

- Renal arteries (L1-L2) supply blood to the kidneys

- Gonadal arteries (between L2 and L3) supply blood to the ovaries (women) or testes (men). In males, gonadal arteries are specifically referred to as testicular arteries. They descend along posterior abdominal wall to pass through inguinal canal and descend into scrotum. In females, gonadal arteries are called ovarian arteries. They are much shorter than testicular arteries and remain within abdominal cavity.

- Inferior phrenic arteries are the first paired branches of abdominal aorta; arise immediately superior to origin of celiac trunk. (Inferior phrenic arteries may also arise from renal arteries.) Inferior phrenic arteries supply the diaphragm and the adrenal glands.

- Lumbar arteries. Four pairs arise from posterolateral surface of abdominal aorta to the pattern of the similar posterior intercostal arteries of thorax; pass laterally into abdominal muscle wall and curve toward anterior aspect of wall. Lumbar arteries supply the lumbar vertebrae, spinal cord and meninges, skin and muscles of posterior and lateral part of abdominal wall.

- Abdominal aorta termination: The abdominal aorta ends near the brim of the pelvis at L4, where it divides into right and left common iliac arteries. These vessels supply blood to lower regions of the abdominal wall, the pelvic organs, and the lower extremities.

- Abdominal aorta key relationships

- posterior to the median arcuate ligament between two crura of diaphragm

- anterior and slightly to the left of the lumbar vertebral bodies

- inferior vena cava (IVC) is on its right

- crossed anteriorly by the splenic vein and body of pancreas between the celiac and superior mesenteric artery origins

- crossed anteriorly by the left renal vein, uncinate process of the pancreas and 3rd part of the duodenum between the superior mesenteric and inferior mesenteric artery origins

Figure 1. Aorta segments

Figure 2. Abdominal aorta

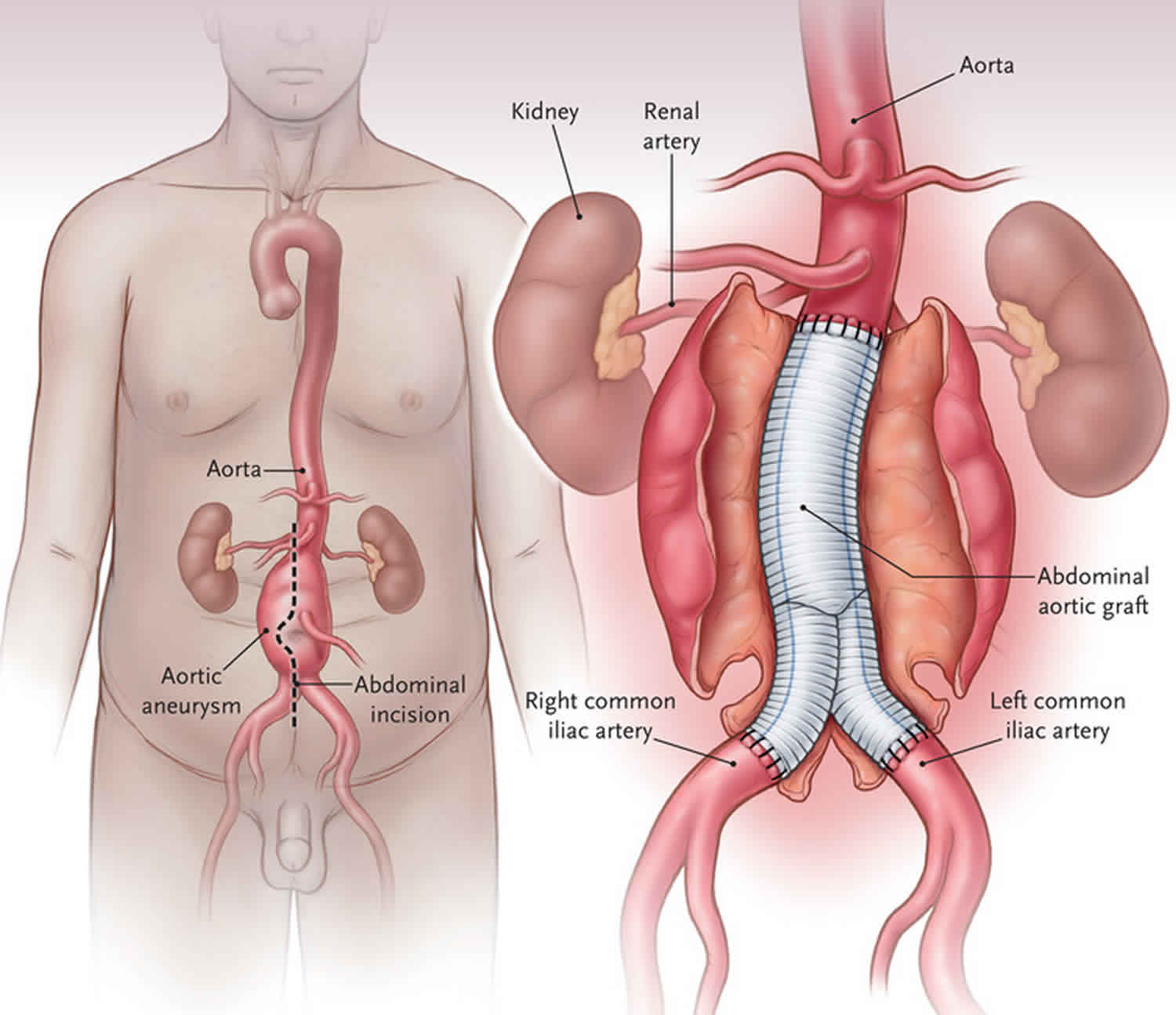

Figure 3. Abdominal aortic aneurysm repair

Abdominal aortic aneurysm risk of rupture

The likelihood that an aneurysm will rupture is influenced by a number of factors including aneurysm size, expansion rate and sex.

Aneurysm size

Aneurysm size is one of the strongest predictors of the risk of rupture, with risk increasing markedly at aneurysm diameters of greater than 5.5 cm 16. The five-year overall cumulative rupture rate of incidentally diagnosed aneurysms in population-based samples is 25% to 40% for aneurysms larger than 5.0 cm, compared with 1% to 7% for aneurysms 4.0 cm to 5.0 cm in diameter 17, 18. A statement from the Joint Council of the American Association for Vascular Surgery and Society for Vascular Surgery estimated the annual rupture risk according to abdominal aortic aneurysm diameter to be the following 19:

- Less than 4.0 cm in diameter – 0%

- 4.0 cm to 4.9 cm in diameter – 0.5% to 5%

- 5.0 cm to 5.9 cm in diameter – 3% to 15%

- 6.0 cm to 6.9 cm in diameter – 10% to 20%

- 7.0 cm to 7.9 cm in diameter – 20% to 40%

- 8.0 cm in diameter or greater – 30% to 50%

Expansion rate

The expansion rate may also be an important determinant of the risk of rupture 20. A small abdominal aortic aneurysm that expands 0.5 cm or more over six months of follow-up is considered to be at high risk for rupture 21. Growth tends to be more rapid in smokers, and less rapid in patients with diabetes or peripheral vascular disease 22.

Other factors

In addition to aneurysm size and expansion rate, other factors that increase the risks of rupture are continued smoking, uncontrolled hypertension and increased wall stress 23.

Society for Vascular Surgery Guidelines on management of patients with Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms

The Society for Vascular Surgery issued updated guidelines on the care of patients with abdominal aortic aneurysms that include the following 24:

- Yearly surveillance imaging in patients with an abdominal aortic aneurysm of 4.0 to 4.9 cm in diameter.

- Assessment of distal leg pulses at each clinic visit.

- For unruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm, endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR) is recommended.

- The endovascular procedure should only be done in a hospital that has performed at least 10 cases every year and has a conversion rate to open of less than 2%

- Elective abdominal aortic aneurysm open surgery should be done in hospitals with a mortality of less than 5%, and that performs at least 10 open cases a year.

- For ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm, a facility with a door to intervention time of less than 90 minutes is preferred.

- Recommend treatment of type 1 and 3 endoleaks as well as of type 2 endoleaks with aneurysm expansion.

- Antibiotic prophylaxis is not recommended before respiratory tract procedures, genitourinary, dermatologic, gastrointestinal, or orthopedic procedures unless there is a potential for infection in an immunocompromised patient.

- Color duplex ultrasonography should be used for postoperative surveillance after Endovascular surgery.

- A preoperative 12-lead electrocardiogram is recommended in all patients undergoing endovascular aneurysm repair or open surgical repair within 4 weeks of the elective surgery.

- If the patient just had a drug-eluting stent placed, open aneurysm surgery should be delayed for at least 6 months; or one can perform endovascular surgery while the patient is on dual antiplatelet therapy.

- Only transfuse blood perioperatively if hemoglobin is less than 7 g/dL.

- Elective repair should be recommended in patients at low risk when the abdominal aortic aneurysm is 5.5 cm.

- The open surgery should be done under general anesthesia.

Abdominal aortic aneurysm symptoms

As the abdominal aortic aneurysm develops, there are usually no symptoms. This can go on slowly for years.

Abdominal aortic aneurysms typically develop slowly over a period of many years and hardly ever cause any noticeable symptoms. Occasionally, especially in thin patients, a pulsating sensation in the abdomen may be felt. The larger an aneurysm grows, the greater the chance it will burst, or rupture.

If you have an enlarging abdominal aortic aneurysm, you might notice:

- Deep, constant pain in the belly area or side of the belly (abdomen)

- Back pain

- A pulse near the bellybutton

Often, abdominal aortic aneurysms don’t cause symptoms unless they leak, tear, or rupture. If this happens, you may experience:

- Sudden pain in your abdomen or back. The pain may be severe, sudden, persistent, or constant. It may spread to your groin, buttocks, or legs.

- Nausea and vomiting.

- Abnormal stiffness in your abdominal muscles.

- Problems with urination or bowel movements.

- Clammy, sweaty skin.

- Passing out.

- Rapid heart rate.

- Low blood pressure.

- Shock.

If you have these symptoms, this is a medical emergency and you should call your local emergency services number immediately. Internal bleeding from a ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm can cause you to go into shock. Shock can be fatal if not treated right away.

Abdominal aortic aneurysm complications

Tears in one or more of the layers of the wall of the aorta (aortic dissection) or a ruptured aneurysm are the main complications. A rupture can cause life-threatening internal bleeding. In general, the larger the aneurysm and the faster it grows, the greater the risk of rupture.

Signs and symptoms that an aortic aneurysm has ruptured can include:

- Sudden, intense and persistent abdominal or back pain, which can be described as a tearing sensation

- Low blood pressure

- Fast pulse

Aortic aneurysms also increase the risk of developing blood clots in the area or thrombotic occlusion of a branch vessel. If a blood clot breaks loose from the inside wall of an aneurysm and blocks a blood vessel elsewhere in your body, it can cause pain or block blood flow to the legs, toes, kidneys or abdominal organs.

Other abdominal aortic aneurysm complications include 25:

- Pseudoaneurysm from chronic contained leak/rupture

- Aortic fistulas

- aortocaval fistula

- aortoenteric fistula

- aorto-left renal vein fistula (very rare)

- Infection/mycotic aneurysm (actually a pseudoaneurysm)

- Compression of adjacent structures from large aneurysms (rare)

- Anterior vertebral scalloping

- Bleeding

- Limb ischemia

- Delayed rupture secondary to endoleak

- Abdominal compartment syndrome

- Myocardial infarction

- Pneumonia

- Graft infection

- Colon ischemia

- Renal failure

- Bowel obstruction

- Blue toe syndrome

- Amputation

- Impotence

- Lymphocele

- Death

Ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm

Abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) rupture is a feared complication of abdominal aortic aneurysm and is a surgical emergency. It is part of the acute aortic syndrome spectrum. In the United States, ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms are estimated to cause 4% to 5% of sudden deaths 26. Patients with ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms classically present with shooting abdominal or back pain and a pulsatile abdominal mass. Aneurysm rupture typically causes severe hypotension. Only approximately 50% of patients with ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms reach the hospital alive; of those who reach the hospital, up to 50% do not survive repair 27.

The aneurysmal rupture is thought to occur when the mechanical stress is in excess of the wall strength. Thus, the aortic aneurysmal wall tension and the aneurysmal diameter are a significant predictor of impending rupture.

Findings predictive of impending rupture 28:

- increased aneurysm size on serial imaging (rate of 10 mm or more per year)

- very large abdominal aortic aneurysm > 7 cm

- reduced thrombus size

- thrombus fissuration

- discontinuity in calcification

- hyperattenuating crescent sign

- well defined peripheral crescent of increased attenuation within the thrombus of a large abdominal aortic aneurysm

The commonest sites of aortic aneurysm rupture and their relative incidences are 28:

- Intraperitoneal rupture: 20%

- Retroperitoneal rupture: 80%

- Aortocaval fistula: 3-4%

- Primary aorto-enteric fistula: < 1%

- Aorto-left renal vein fistula: very rare; < 30 cases reported

Ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm symptoms

Ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm symptoms are the classic triad of sudden-onset of severe abdominal, chest, or back pain, hypotension, and hemorrhagic shock due to massive intra-abdominal bleeding, which is only seen in 25% to 50% of ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm cases 29, 28, causing frequent misdiagnosis as myocardial infarction, ureteric colic, or perforated gastrointestinal ulcer 30.

The rupture varies in location and extent, but if not surgically repaired immediately, it typically leads to fatal internal bleeding 31. Retroperitoneal (posterolateral) rupture is observed most frequently, at about 80%, where bleeding may be temporarily restrained by a tamponade effect 32. Around 20% of ruptures occur anteriorly, with mostly rapid intraperitoneal bleeding and patient death. Rupture in combination with the formation of an aortocaval fistula (3–4%) or a primary aortoduodenal fistula (<1%) are comparably rare events 32.

A chronic rupture may escape detection for about weeks to months and are known as sealed aneurysmal rupture or spontaneously healed aneurysmal rupture or abdominal aortic aneurysmal leak 28.

Unusual presentations of ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm are 28:

- transient lower-limb paralysis

- right upper quadrant pain

- groin pain

- testicular pain

- testicular ecchymosis (blue scrotum sign of Bryant)

- iliofemoral venous thrombosis

Ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm treatment and prognosis

Treatment of an acute rupture should be prompt and can be with endovascular aneurysm repair or open surgery. The mortality rate is very high being > 90% 12.

Depending on the hemodynamic situation, an immediate computed tomography angiography (CTA), or alternatively, an intraoperative angiography is indicated to confirm the diagnosis and evaluate anatomical suitability for endovascular aortic aneurysm repair 33. Both open surgical repair and endovascular aortic aneurysm repair can be used for ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm repair, with endovascular aortic aneurysm repair being the method of choice if anatomically feasible. Endovascular aortic aneurysm repair and open surgery for ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm have comparable morbidity rates and show no difference in cardiac or respiratory failure 34. Reintervention rates are similar, as well, and endovascular aortic aneurysm repair is consistently associated with faster discharge and a gain in quality-adjusted life years, rendering it cost-effective 35.

As with elective abdominal aortic aneurysm repairs, use of endovascular aortic aneurysm repair for ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm repair has increased massively in the past two decades 36, 34. Analyses of earlier versus later cohorts show that outcomes have improved in recent years for both endovascular aortic aneurysm repair and open surgical repair 37, 38. High mortality rates of unsuccessful endovascular aortic aneurysm repair for ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm suggest that anatomical suitability and not hemodynamic condition should be the pivotal factor in choosing the surgical method for ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm repair 34, 39.

Abdominal aortic aneurysm causes

It’s not known exactly what causes abdominal aortic aneurysm although it is linked to atherosclerosis and the build-up of fatty material in your arteries. Atherosclerosis (also known as arteriosclerosis) is a chronic degenerative disease of the artery wall, in which fat, cholesterol, and other substances build up in the walls of arteries and form soft or hard deposits called plaques. Weaker aorta walls also increases your chance of developing an aneurysm. There are many conditions that can weaken the walls of the aorta. These include aging, smoking, and high blood pressure.

If any of the following factors apply to you, you are at higher risk of having an abdominal aortic aneurysm.

- Being male. Men are more likely than women to develop an abdominal aortic aneurysm.

- Age 65 or older. Abdominal aortic aneurysms are more common in people age 65 or older.

- Abdominal aortic aneurysm is far more common in men over 65. For this reason, all men are invited for a screening test when they turn 65. This test involves a simple ultrasound scan and takes around 10-15 minutes.

- If you are female or under 65 and think that you may have AAA or are at risk of developing it, then speak to your doctor about the possibility of being referred for an ultrasound scan.

- Personal history. If you have had aneurysms of any kind, you are at greater risk of an abdominal aortic aneurysm.

- Smoking damages and weakens the aorta walls. A study found smoking to be the risk factor most strongly associated with abdominal aortic aneurysm 40. The association with smoking was directly related to the number of years of smoking, and the association decreased with the number of years after cessation of smoking 11.

- High blood pressure. Having high blood pressure weakens the walls of your aorta.

- Family history. If any family members have had abdominal aortic aneurysms, you are at higher risk of developing the condition. You also could get an abdominal aortic aneurysm before you are 65. One in 10 people with abdominal aortic aneurysms have a family history of abdominal aortic aneurysms. The chance of developing an abdominal aortic aneurysm is 1 in 5 for people who have a first degree relative with the condition, which means a parent, brother, sister, or child was affected. If someone in your family have had an abdominal aortic aneurysm consult your doctor who may recommend an earlier screening. A genetic predisposition has been suspected since the first report of three brothers who had a ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm, and additional families with multiple affected relatives have been reported 41. In some cases, it may be referred to as ” familial abdominal aortic aneurysm” 42. A Swedish survey reported that the relative risk of developing abdominal aortic aneurysm for a first-degree relative of a person with abdominal aortic aneurysm was approximately double that of a person with no family history of abdominal aortic aneurysm. In another study, having a family history increased the risk of having an aneurysm 4.3-fold. The highest risk was among brothers older than age 60, in whom the prevalence was 18% 41. While specific variations in DNA (polymorphisms) are known or suspected to increase the risk for abdominal aortic aneurysm, no one gene is known to cause isolated abdominal aortic aneurysm. It can occur with some inherited disorders that are caused by mutations in a single gene, such as Marfan syndrome and Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, vascular type. However, these more typically involve the thoracoabdominal aorta 41. Because the inheritance of abdominal aortic aneurysm is complex, it is not possible to predict whether a specific person will develop abdominal aortic aneurysm. People interested in learning more about the genetics of abdominal aortic aneurysm, and how their family history affects risks to specific family members, should speak with a genetics professional.

Talk to your doctor if you have a higher risk for an abdominal aortic aneurysm, or if you have any of the symptoms.

Your doctor may order an ultrasound of your abdomen to screen for an aneurysm.

- Most men between the ages of 65 to 75, who have smoked during their life should have this test one time.

- Some men between the ages of 65 to 75, who have never smoked during their life may need this test one time.

Risk factors for developing abdominal aortic aneurysm

Abdominal aortic aneurysm risk factors include:

- Tobacco use. Smoking is the strongest risk factor for aortic aneurysms 21. Smoking can weaken the walls of the aorta, increasing the risk of aortic aneurysm and aneurysm rupture. The longer and more you smoke or chew tobacco, the greater the chances of developing an aortic aneurysm. Doctors recommend a one-time abdominal ultrasound to screen for an abdominal aortic aneurysm in men ages 65 to 75 who are current or former cigarette smokers.

- Old age. Abdominal aortic aneurysms occur most often in people age 65 and older (~10% of patients older than 65 years have an abdominal aortic aneurysm).

- Being male. Men develop abdominal aortic aneurysms much more often than women do (4:1 male/female ratio).

- Being white. White men have the highest risk of developing abdominal aortic aneurysms. They are uncommon in Asian, African American, and Hispanic individuals 43.

- Family history. Having a family history of abdominal aortic aneurysms increases the risk of having the condition. If a first-degree relative has had an AAA, you are 12 times more likely to develop an abdominal aortic aneurysm. Of patients in treatment to repair an AAA, 15–25% have a first-degree relative with the same type of aneurysm.

- Other aneurysms. Having an aneurysm in another large blood vessel, such as the artery behind the knee or the aorta in the chest (thoracic aortic aneurysm), might increase the risk of an abdominal aortic aneurysm.

- Prior history of aortic dissection

- Hypertension

- Hypercholesterolemia

- Cystic medial necrosis

- Syphilis

- HIV

- Connective tissue diseases (Ehlers-Danlos, Marfan, Loeys-Dietz syndromes)

If you’re at risk of an aortic aneurysm, your doctor might recommend other measures, such as medications to lower your blood pressure and relieve stress on weakened arteries.

Abdominal aortic aneurysm pathophysiology

Abdominal aortic aneurysms tend to occur when there is a failure of the structural proteins of the aorta. What causes these proteins to fail is not known, but it results in the gradual weakening of the aortic wall. The decrease in structural proteins of the aortic wall such as elastin and collagen has been identified 44. The composition of the aortic wall is made of collagen lamellar units. The number of lamellar units is lower in the infrarenal aorta than the thoracic aorta 45. This is felt to contribute to the higher incidence of aneurysmal formation in the infrarenal aorta. A chronic inflammatory process in the wall of the aorta has been identified but is of unclear cause 46.

Other factors that may play a role in the development of these aneurysms include genetics, marked inflammation, and proteolytic degradation of the connective tissue in the aortic wall 47.

Autopsy studies usually show marked degeneration of the media. Examination of resected abdominal aortic aneurysms usually reveals a state of chronic inflammation with an infiltrate of neutrophils, macrophages, and lymphocytes. The media is often thin, and there is evidence of degeneration of the connective tissue.

Abdominal aortic aneurysm prevention

You can’t always prevent an abdominal aortic aneurysm from forming. But there are steps you can take to lower your risk or keep an aortic aneurysm from worsening. These include:

- Don’t smoke. Quit smoking or chewing tobacco and avoid secondhand smoke. If you are a smoker and you need help quitting, talk to your doctor about medications and therapies that may help.

- Eat a healthy diet. Focus on eating a variety of fruits and vegetables, whole grains, poultry, fish, and low-fat dairy products. Avoid saturated and trans fats and limit salt.

- Be physically active. Try to get at least 150 minutes a week of moderate aerobic activity. If you haven’t been active, start slowly and build up. Talk to your doctor about what kinds of activities are right for you.

- Keep to a healthy weight.

- Manage conditions such as high blood pressure, high cholesterol and diabetes that can be controlled with medicine.

- Reduce stress.

Taking these steps can also help reduce the risk of your abdominal aortic aneurysm growing larger if you already have one.

People over age 65 who have ever smoked should have a screening ultrasound done once.

Your doctor may order an ultrasound of your abdomen to screen for an aneurysm.

- Most men between the ages of 65 to 75, who have smoked during their life should have this test one time.

- Some men between the ages of 65 to 75, who have never smoked during their life may need this test one time.

Abdominal aortic aneurysm diagnosis

Doctors commonly find abdominal aortic aneurysms by chance during a routine exam. They also find them when doing tests for other issues, including unrelated pain in your abdomen. Doctors recommend an abdominal aortic aneurysm screening for men ages 65 to 75 who have ever smoked.

To diagnose an abdominal aortic aneurysm, a doctor will examine you and review your medical and family history. If your doctor thinks that you may have an aortic aneurysm, imaging tests are done to confirm the diagnosis.

Common tests to diagnose an abdominal aortic aneurysm include:

- Abdominal ultrasound or echocardiogram – These use sound waves to create pictures of the inside of your body. Duplex ultrasound is the recommended modality for screening and diagnosis of asymptomatic patients 48, as it allows safe, noninvasive, and fast detection of abdominal aortic aneurysms with high sensitivity and specificity 49. Duplex ultrasound can also be used in emergency settings for rapid assessment of symptomatic patients 50, but emergency conditions with possible active bleeding after rupture or endoleaks after endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR) usually warrant an additional computed tomography angiography (CTA) due to inherent methodological limitations of ultrasound scans. For instance, adjacent vessels may be difficult to assess, and imaging methodology influences diameter measurements 51.

- Abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan – This painless test uses X-rays to create cross-sectional images of the structures inside the belly area. It’s used to create clear images of the aorta. An abdominal CT scan can also detect the size and shape of an aneurysm. During a CT scan, you lie on a table that slides into a doughnut-shaped machine. Sometimes, dye (contrast material) is given through a vein to make your blood vessels show up more clearly on the images.

- Computed tomography angiography (CTA) is the gold standard for the diagnosis of abdominal aortic aneurysm rupture, therapeutic decision making, and treatment planning, as well as post-surgical assessment and follow-up 52. Computed tomography angiography (CTA) provides detailed anatomical information on the entire aorta and its adjacent vessels, allowing assessment of the extent of the abdominal aortic aneurysm, and of possible acute and chronic comorbid pathologies and, thus, exact planning of surgical intervention 53. Due to its wide availability, rapid image acquisition, and lower radiation burden, CTA has virtually rendered conventional invasive angiography for the evaluation of abdominal aortic aneurysm obsolete.

- Abdominal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) – This imaging test uses a magnetic field and computer-generated radio waves to create detailed images of the structures inside your belly area. Sometimes, dye (contrast material) is given through a vein to make your blood vessels more visible.

- Angiography – This test uses dye and X-rays to look at the inside of your arteries. This can help your doctor see how much damage or blockage there is in your blood vessels.

If your doctor finds or thinks you might have an abdominal aortic aneurysm, he or she might refer to you a specialist for treatment.

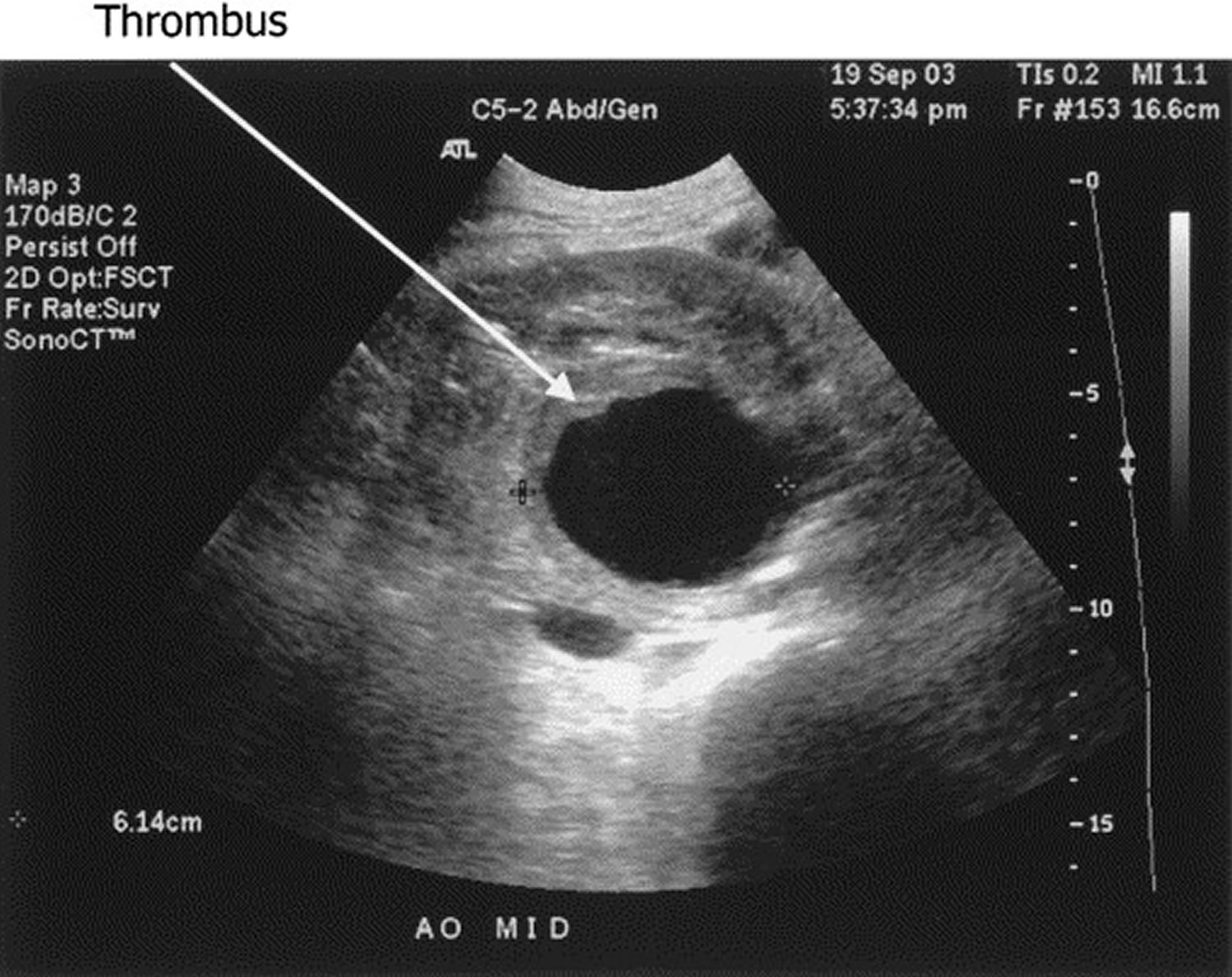

Abdominal aortic aneurysm ultrasound

Abdominal ultrasound is the most common test to diagnose abdominal aortic aneurysms. An abdominal ultrasound is a painless test that uses sound waves to show how blood flows through the structures in the belly area, including the aorta. During an abdominal ultrasound, a technician gently presses an ultrasound wand (transducer) against the belly area, moving it back and forth. The device sends signals to a computer, which creates images.

Figure 4. Abdominal aortic aneurysm ultrasound

Abdominal aortic aneurysm screening

You may have an abdominal aortic aneurysm that is not causing any symptoms. Being male and smoking significantly increase the risk of abdominal aortic aneurysm. Your doctor may order an ultrasound of your abdomen to screen for an aneurysm.

- Most men between the ages of 65 to 75, who have smoked during their life should have a one-time screening using abdominal ultrasound.

- Some men between the ages of 65 to 75, who have never smoked during their life may need a one-time screening using abdominal ultrasound.

- Men and women 65 to 75 years old who have ever smoked or who have a first-degree relative who had an abdominal aortic aneurysm

- Men 65 to 75 years old who never smoked but have other risk factors, such as a family history of abdominal aortic aneurysms in any family member, other vascular aneurysms, or coronary heart disease

- Men and women more than 75 years old who are in good health, who have ever smoked, or who have a first-degree relative who had an abdominal aortic aneurysm.

- People who have peripheral artery disease, regardless of age, sex, smoking history, or family history

The United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) makes the following recommendations 54:

| Population | Recommendation | Grade |

|---|---|---|

| Men aged 65 to 75 years who have ever smoked | The USPSTF recommends 1-time screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) with ultrasonography in men aged 65 to 75 years who have ever smoked. | B |

| Men aged 65 to 75 years who have never smoked | The USPSTF recommends that clinicians selectively offer screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) with ultrasonography in men aged 65 to 75 years who have never smoked rather than routinely screening all men in this group. Evidence indicates that the net benefit of screening all men in this group is small. In determining whether this service is appropriate in individual cases, patients and clinicians should consider the balance of benefits and harms on the basis of evidence relevant to the patient’s medical history, family history, other risk factors, and personal values. | C |

| Women who have never smoked | The USPSTF recommends against routine screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) with ultrasonography in women who have never smoked and have no family history of AAA. | D |

| Women aged 65 to 75 years who have ever smoked | The USPSTF concludes that the current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of screening for AAA with ultrasonography in women aged 65 to 75 years who have ever smoked or have a family history of abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA). | I |

Footnotes:

- Grade A = The USPSTF recommends the service. There is high certainty that the net benefit is substantial.

- Grade B = The USPSTF recommends the service. There is high certainty that the net benefit is moderate or there is moderate certainty that the net benefit is moderate to substantial.

- Grade C = The USPSTF recommends selectively offering or providing this service to individual patients based on professional judgment and patient preferences. There is at least moderate certainty that the net benefit is small.

- Grade D = The USPSTF discourages the use of this service. There is moderate or high certainty that the service has no net benefit or that the harms outweigh the benefits.

- Grade I = The USPSTF concludes that the current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of the service. Evidence is lacking, of poor quality, or conflicting, and the balance of benefits and harms cannot be determined.

Screening recommendations vary, so your doctor will decide on the need for an abdominal ultrasound based on other risk factors, such as a family history of aneurysm.

Furthermore, there isn’t enough evidence to determine whether women ages 65 to 75 who ever smoked cigarettes or have a family history of abdominal aortic aneurysm would benefit from abdominal aortic aneurysm screening. Ask your doctor if you need to have an ultrasound screening based on your risk factors. Women who have never smoked generally don’t need to be screened for the condition 55.

Abdominal aortic aneurysm treatment

Treatment for an abdominal aortic aneurysm depends on its size, location and your overall health. Aortic aneurysms in the upper chest (the ascending aorta) are usually operated on right away. Aneurysms in the lower chest and the area below your stomach (the descending thoracic and abdominal parts of the aorta) may not be as life threatening. Aneurysms in these locations are watched for varying periods, depending on their size. Patients with small abdominal aortic aneurysms measuring 3.0 to 3.9 cm in diameter should be followed with imaging surveillance in the form of duplex ultrasonography every 3 years, whereas those with aneurysms measuring 4.0 to 4.9 cm in diameter should be followed once a year and those with aneurysms that are 5.0 cm in diameter or larger should be followed every 3 to 6 months 56, 57, but may be adapted according to individual patient factors, such as fast aneurysm growth or high peak wall stress 58, 59.

Most aneurysms are small (between 3 and 5.4 cm) and it might not need to be treated. Your doctor may just monitor it with regular scans to check the size of the aortic aneurysm. All patients with small abdominal aortic aneurysms who do not undergo repair need periodic follow up with an ultrasound every 6 to 12 months to ensure that the aneurysm is not expanding 60. If your doctor is concerned about it, he or she may prescribe medicine. These can be used to lower blood pressure or relax blood vessels. This can help prevent the abdominal aortic aneurysm from rupturing. If your abdominal aortic aneurysm is large (more than 5.5 cm) or is growing quickly, you will most likely need surgery.

If an abdominal aortic aneurysm becomes about 5 centimeters (almost 2 inches) in diameter, continues to grow, or begins to cause symptoms, you may need surgery to repair the artery before the aneurysm bursts.

Small abdominal aortic aneurysms (less than 5 cm in diameter) have a very low risk of rupturing, but should be watched.

- It’s important to have an ultrasound test every 6–12 months to monitor for aneurysm growth and risk of rupture.

- Lifestyle changes that help control blood pressure and medication may help you.

- If you smoke, ask your vascular surgeon to help you find a smoking cessation program that will work for you.

- Daily exercise is also beneficial.

Larger (more than 5.0-5.5 cm in diameter) rapidly enlarging and abdominal aortic aneurysms causing symptoms are usually repaired.

If you have bleeding inside your body from an aortic aneurysm, you will need surgery right away. The type of surgery you have depends on many factors. Talk to your doctor about which kind is best for you.

If the aneurysm is small and there are no symptoms:

- Surgery is rarely done.

- You and your doctor must decide if the risk of having surgery is smaller than the risk of bleeding if you do not have surgery.

- Your doctor may want to check the size of the aneurysm with ultrasound tests every 6 months.

Most of the time, surgery is done if the aneurysm is bigger than 2 inches (5 centimeters) across or if the aneurysm is growing more quickly (a little less than 1/4 inch over the last 6 to 12 months). The goal is to do surgery before complications develop.

Medical monitoring

A doctor might recommend this option, also called watchful waiting, if the abdominal aortic aneurysm is small and isn’t causing symptoms. Monitoring requires regular doctor’s checkups and imaging tests to determine if the aneurysm is growing and to manage other conditions, such as high blood pressure, that could worsen the aneurysm.

Typically, a person who has a small, symptomless abdominal aortic aneurysm needs an abdominal ultrasound at least six months after diagnosis and at regular follow-up appointments.

The rate of enlargement for small abdominal aortic aneurysm (3-5 cm) is 0.2 to 0.3 cm/year and 0.3 to 0.5 cm/year for those > 5 cm 61. The pressure on the aortic wall follows the Law of Laplace (wall stress is proportional to the radius of the aneurysm). Because of this, larger aneurysms are at higher risk of rupture, and the presence of hypertension also increases this risk.

Timing of repair

Randomized trials showing no survival advantage with surgery over close surveillance for abdominal aortic aneurysms measuring less than 5.5 cm have supported the view that this diameter represents an appropriate threshold for repair and that surveillance for aneurysms with a diameter that is less than 5.5 cm is safe and cost-effective 14. Although intervention thresholds for the surveillance groups in these trials also included rapid growth of the aneurysm (defined as a rate of growth of >1 cm per year), rigorous data are lacking to support repair on the basis of rapid growth 62. An important limitation of the studies on which the threshold of 5.5 cm is based is that the overwhelming majority of patients enrolled were White men; thus, the generalizability of the findings to women and other races and ethnic groups is unclear. Given the smaller native size of the aorta and the higher incidence of rupture of small abdominal aortic aneurysms among women 63, most experts and guidelines suggest that a smaller diameter of 5.0 cm is an appropriate threshold for repair in women 5, 48.

Beta-blockers

Although the data regarding therapeutic benefit of beta-blockers in management of abdominal aortic aneurysm are limited, beta-blockers have been shown to significantly reduce the expansion rate of abdominal aortic aneurysm when monitored by serial ultrasound examination 20. The 2005 American College of Cardiology (ACC) and American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines recommended beta-blocker therapy in patients with an abdominal aortic aneurysm who do not undergo surgery 21. Because of the possible attenuation of aneurysm expansion, beta-blockers are also a preferred drug for patients with hypertension or angina with care taken in patients with atrioventricular blocks, bradycardia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and peripheral vascular disease.

Antibiotic therapy

Interest in antibiotic therapy in the management of abdominal aortic aneurysm is based on evidence of chronic inflammation in abdominal aortic aneurysm, inhibition of proteases and inflammation by antibiotics, and possible involvement of Chlamydia pneumoniae in the pathogenesis of abdominal aortic aneurysm 16. A study 64 evaluating the role of antibiotics in the management of abdominal aortic aneurysm found a reduction in the mean annual expansion rate of the aneurysms among patients receiving an antibiotic (roxithromycin) compared with those receiving placebo therapy. Also, long-term use of antibiotics has been associated with an increased risk for breast cancer 65)). With uncertain benefits and known harms, more reassuring data are needed before this approach can be recommended.

Abdominal aortic aneurysm surgery

Surgery to repair an abdominal aortic aneurysm is generally recommended if the aneurysm is 1.9 to 2.2 inches (4.8 to 5.6 centimeters) or larger, or if it’s growing quickly. Also, a doctor might recommend abdominal aortic aneurysm repair surgery if you have symptoms such as stomach pain or you have a leaking, tender or painful aneurysm. For aneurysms between 4 cm and 5.5 cm, a few studies concluded that the likelihood of eventual surgical requirement is 60% to 65% at five years, and 70% to 75% at the end of eight years 66, 67. A review 68 indicated that there was no significant difference in all-cause mortality between open repair and imaging surveillance at the end of five to eight years in these patients.

The type of surgery performed depends on the size and location of the aneurysm, your age, and your overall health. There are 2 main kinds of surgery to remove or repair abdominal aortic aneurysms:

- Open abdominal surgery – This is the most common form of surgery for an abdominal aortic aneurysm. The surgeon will make an incision (cut) in your abdomen. He or she will remove the aneurysm. The removed section of the aorta is replaced with a graft made of man-made material. Open abdominal surgery is a big operation and you will need a general anaesthetic, so you will be asleep for the procedure. Most people who have this operation need to stay in hospital for over a week and it can take some weeks to make a full recovery.

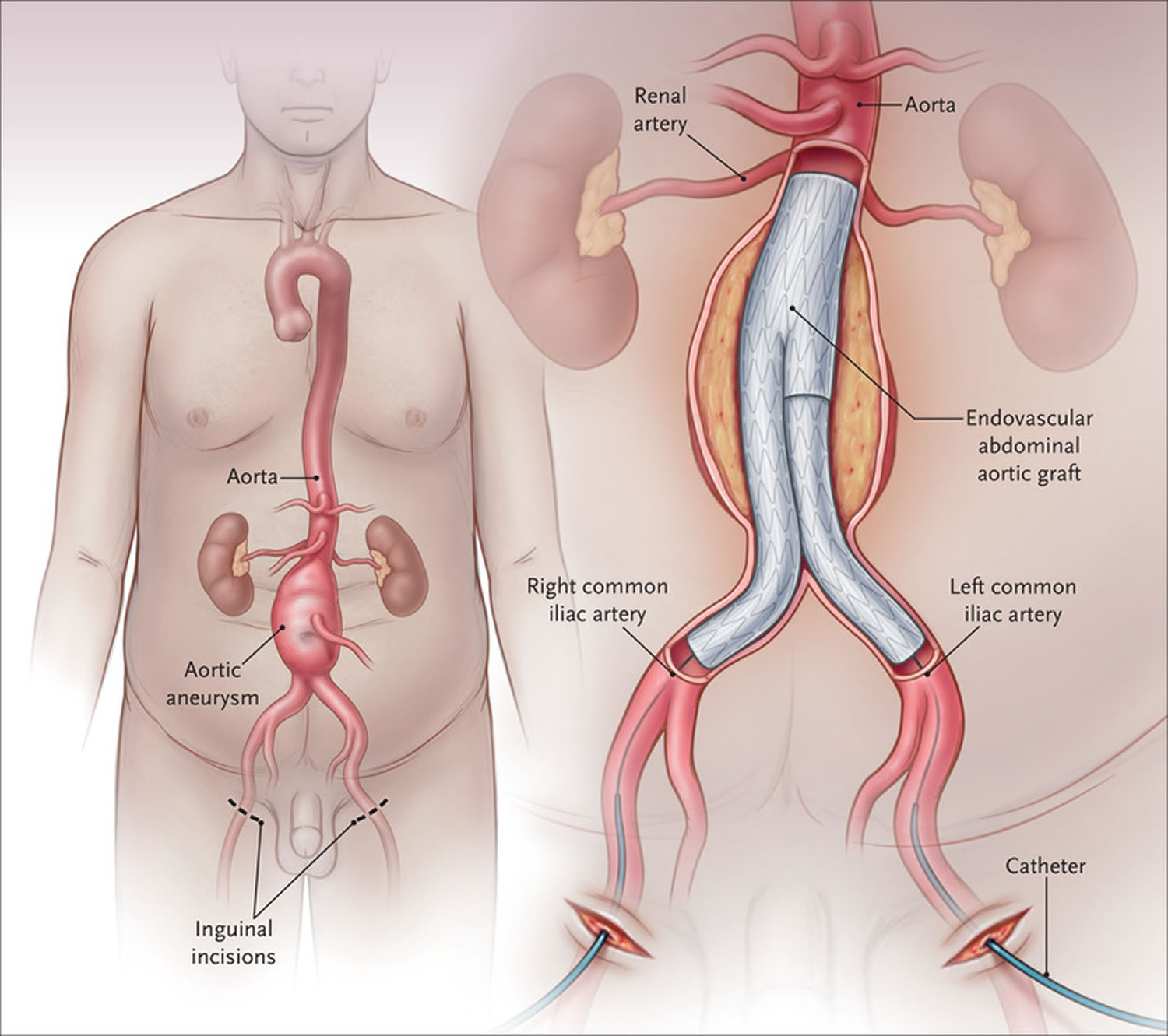

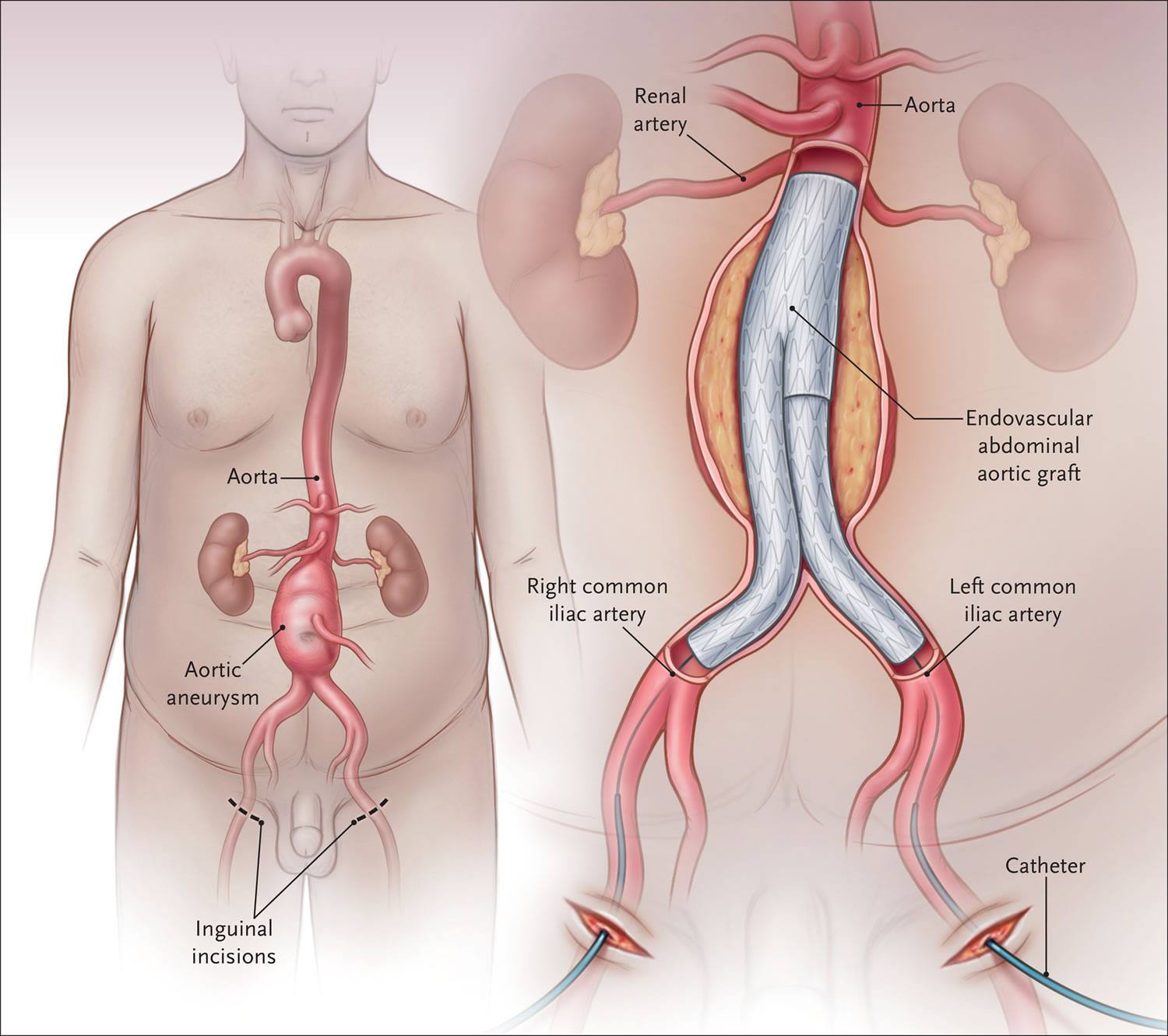

- Endovascular repair – This procedure can be done without making a large cut in your abdomen, so you may recover more quickly. In this procedure, your doctor inserts a graft into the aorta to strengthen it. He or she will insert a catheter (tube) into your artery through your leg. The graft will be threaded through the aneurysm and expanded. This will reinforce the weak section of the aorta and allow blood to flow normally. This helps keep the abdominal aortic aneurysm from rupturing. Endovascular repair may be a safer approach if you have certain other medical problems or are an older adult. Endovascular repair can sometimes be done for a leaking or bleeding aneurysm. If you have this procedure you will usually have a local anaesthetic, although some people might need a general anaesthetic. You should be able to get up and walk around the next day. Most people are able to go home two or three days afterwards. Although this is a simpler and safer procedure than open surgery, it’s not suitable for everyone. Your surgeon will discuss your options with you.

Most people who have an aneurysm repaired before it breaks open (ruptures) have a good outlook.

Data show that for unruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms, endovascular repair has no long-term differences in outcomes compared to open repair 3. However, data indicates that expansion of the neck of the aorta continues despite endovascular therapy, which is of concern. The need to take beta-blockers cannot be understated in these patients. An open repair has been the gold standard for abdominal aortic aneurysm repair for many decades. It involves a long midline incision followed by replaced of the diseased aorta with a graft. Postoperatively, these patients do need close monitoring in the ICU for 24-48 hours.

If surgery isn’t appropriate you will have regular scans and advice around lifestyle choices and medications from your doctor.

Abdominal aortic aneurysm open surgery

Open abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) repair is a surgery to fix a widened part in your abdominal aorta (an aneurysm). The abdominal aorta is the large artery that carries blood to your belly (abdomen), pelvis, and legs. In an open abdominal surgery, your surgeon will make an incision (cut) in your abdomen. He or she will remove the aneurysm. The removed section of the aorta is replaced with a graft made of man-made material.

Open surgery to repair an abdominal aortic aneurysm is sometimes done as an emergency procedure when there is bleeding inside your body from the aneurysm.

The surgery will take place in an operating room. You will be given general anesthesia (you will be asleep and pain-free).

Here is how it can be done:

- In one approach, you will lie on your back. The surgeon will make a cut in the middle of your belly, from just below the breastbone to below the belly button. Rarely, the cut goes across the belly.

- In another approach, you will lie slightly tilted on your right side. The surgeon will make a 5- to 6-inch (13 to 15 centimeters) cut from the left side of your belly, ending a little below your belly button.

- Your surgeon will replace the aneurysm with a long tube made of man-made (synthetic) cloth. It is sewn in with stitches.

- In some cases, the ends of this tube (or graft) will be moved through blood vessels in each groin and attached to those in the leg.

- Once the surgery is done, your legs will be examined to make sure that there is a pulse. Most often a dye test using x-rays is done to confirm that there is good blood flow to the legs.

- The cut is closed with sutures or staples.

Surgery for aortic aneurysm replacement may take 2 to 4 hours. Most people recover in the intensive care unit (ICU) after the surgery. Most patients stay in the hospital 4–10 days.

Full recovery for open surgery to repair an aortic aneurysm may take 2 or 3 months. Most people make a full recovery from this surgery.

Before the procedure

Your will have a physical exam and get tests before you have surgery. Always tell your doctor what medicines you are taking, even drugs, supplements, or herbs you bought without a prescription.

If you are a smoker, you should stop smoking at least 4 weeks before your surgery. Your doctor can help.

During the 2 weeks before your surgery:

- You will have visits with your doctor to make sure medical problems such as diabetes, high blood pressure, and heart or lung problems are well treated.

- You may be asked to stop taking drugs that make it harder for your blood to clot. These include aspirin, ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin), clopidogrel (Plavix), naprosyn (Aleve, Naproxen), and other drugs like these.

- Ask which drugs you should still take on the day of your surgery.

- Always tell your doctor if you have a cold, flu, fever, herpes breakout, or other illness before your surgery.

DO NOT drink anything after midnight the day before your surgery, including water.

On the day of your surgery:

- Take the drugs you were told to take with a small sip of water.

- You will be told when to arrive at the hospital.

After the procedure

Most people stay in the hospital for 5 to 10 days. During a hospital stay, you will:

- Be in the intensive care unit (ICU), where you will be monitored very closely right after surgery. You may need a breathing machine during the first day.

- Have a urinary catheter.

- Have a tube that goes through your nose into your stomach to help drain fluids for 1 or 2 days. You will then slowly begin drinking, then eating.

- Receive medicine to keep your blood thin.

- Be encouraged to sit on the side of the bed and then walk.

- Wear special stockings to prevent blood clots in your legs.

- Be asked to use a breathing machine to help clear your lungs.

- Receive pain medicine into your veins or into the space that surrounds your spinal cord (epidural).

Endovascular repair

Endovascular repair procedure is used most often to repair an abdominal aortic aneurysm. Endovascular repair is a type of keyhole surgery. This involves placing a stent-graft (a small metal tube covered with a mesh) inside the aorta through a small cut in your groin. A surgeon inserts a thin, flexible tube (catheter) through an artery in your leg and gently guides it to the aorta. A metal mesh tube (graft) on the end of the catheter is placed at the site of the aneurysm, expanded and fastened in place. The graft strengthens the weakened section of the aorta to prevent rupture of the aneurysm.

If you have this procedure you will usually have a local anesthetic, although some people might need a general anesthetic. You should be able to get up and walk around the next day. Most people are able to go home two or three days afterwards. Recovery time is shorter than with open surgery. After endovascular surgery, you’ll need regular imaging tests to ensure that the grafted area isn’t leaking.

Although this is a simpler and safer procedure than open surgery, endovascular surgery is not suitable for everyone. You and your surgeon will discuss the best repair option for you.

The three largest randomized, controlled trials performed to date in which the outcomes of elective open surgical repair were compared with outcomes of endovascular aortic aneurysm repair have yielded consistent results 69, 70, 71. All three trials showed that 30-day morbidity and mortality were significantly lower with endovascular aortic aneurysm repair than with open surgical repair (0.5 to 1.7% vs. 3.0 to 4.7%) 69, 70, 71. Recovery is faster in patients who undergo endovascular aortic aneurysm repair (median length of hospital stay in Medicare beneficiaries is 2 days vs. 7 days with open surgical repair) 72. However, the short-term survival advantage of endovascular aortic aneurysm repair diminishes during follow-up, such that among the patients who survived beyond 2 to 3 years, survival rates associated with the two procedures were similar, and they remained so during 8 to 10 years of follow-up. Reintervention rates after endovascular aortic aneurysm repair were higher than those observed after open surgical repair, but most follow-up procedures were performed with catheter-based techniques; overall, the costs of endovascular aortic aneurysm repair were higher than those associated with open surgery. Data from clinical experience in the United States have supported the findings of these trials 72.

It is unclear why trials consistently show that the substantial early survival benefit conferred by endovascular aortic aneurysm repair, as compared with open repair, is not maintained beyond 2 to 3 years. Possible reasons are underlying cardiovascular risk; poor adherence to recommendations for follow-up care (which may result from inadequate counseling or insufficient understanding of recommendations) 73; persistence of an elevated inflammatory state associated with the presence of an intact aneurysm, leading to cardiovascular events (an outcome that requires study) 74; persistent sac pressurization without endoleak that is identifiable on imaging 75; and device failures 76.

Although stent-graft fatigue explains some device failures, many failures can be explained by inappropriate placement — that is, the stent is placed in a patient whose anatomy is inappropriate for placement according to the instructions for use. Unfavorable anatomy has been reported in 18 to 63% of patients in whom endovascular aortic aneurysm repair is performed and is clearly associated with worse outcomes 77, 78. If the widespread application of this technique continues to grow in patients with unfavorable anatomy, the short-term benefits will be offset by increased rates of treatment failure, costly reinterventions, and the potential for aneurysm rupture at any time during follow-up 2.

Figure 5. Endovascular repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm

Footnote: Endovascular repair of an infrarenal abdominal aortic aneurysm. Percutaneous femoral artery access is obtained or small incisions are made to expose the femoral arteries for the purpose of introducing stent grafts, under radiologic guidance, to exclude blood flow to the aneurysm.

[Source 2 ]Life after abdominal aortic aneurysm surgery

After aneurysm surgery, your doctor will recommend that you join a cardiac rehabilitation program. These programs help you make lifestyle changes such as modifying your diet, exercising to get your strength back, quitting smoking, maintaining a healthy weight, and learning to deal with stress.

If you have an office job, you can go back to work in about 4 weeks. If you have a more physically demanding job, you may have to wait 6 to 8 weeks, or more.

Abdominal aortic aneurysm surgery risks

The risk of surgery is influenced by the patient’s age, the presence of renal failure, and the status of the cardiopulmonary system 79.

The risks for abdominal aortic aneurysm surgery are higher if you have:

- Heart disease

- Kidney failure

- Lung disease

- Past stroke

- Other serious medical problems

Complications are also higher for older people.

Risks for abdominal aortic aneurysm surgery are:

- Bleeding before or after surgery

- Damage to a nerve, causing pain or numbness in the leg

- Damage to your intestines or other nearby organs

- Loss of blood supply to a portion of the large intestine causing delayed bleeding in the stool

- Infection of the graft

- Injury to the ureter, the tube that carries urine from your kidneys to your bladder

- Kidney failure that may be permanent

- Lower sex drive or inability to get an erection

- Poor blood supply to your legs, your kidneys, or other organs

- Spinal cord injury

- Wound breaks open

- Wound infections

- Death

Risks for any surgery are:

- Blood clots in the legs that may travel to the lungs

- Breathing problems

- Heart attack or stroke

- Infection, including in the lungs (pneumonia), urinary tract, and belly

- Reactions to medicines

Lifestyle and home remedies

For an abdominal aortic aneurysm, a doctor will likely suggest avoiding heavy lifting and vigorous physical activity to prevent extreme increases in blood pressure, which can put more pressure on an aneurysm.

Emotional stress can raise blood pressure, so try to avoid conflict and stressful situations. If you’re feeling stressed or anxious, let your doctor know so that together you can come up with the best treatment plan.

Abdominal aortic aneurysm prognosis

The outcome of an abdominal aortic aneurysm is often good if you have surgery to repair the aneurysm before it ruptures.

When an abdominal aortic aneurysm begins to tear or ruptures, it is a medical emergency. The mortality rate from a ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm is high. Only about 1 in 5 people survive a ruptured abdominal aneurysm 25:

- About 70% (range 59-83%) of patients die before hospitalization or surgery

- for those who undergo operative repair, the mortality rate is ~40%

- for comparison, mortality from elective surgical repair is 4-6%.

It is estimated that 70% of patients after repair will survive for 5 years.

Predictors of mortality include preoperative cardiac arrest, age >80, female gender, massive blood loss, and ongoing transfusion 80. In a patient with a ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm, the one factor that determines mortality is the ability to get proximal control. For those undergoing elective repair, the prognosis is good to excellent. However, long-term survival depends on other comorbidities like chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, heart disease, and peripheral vascular disease.

- Lederle F.A., Johnson G.R., Wilson S.E., Chute E.P., Littooy F.N., Bandyk D.F., Krupski W.C., Barone G.W., Acher C.W., Ballard D.J. Prevalence and Associations of Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Detected through Screening. Aneurysm Detection and Management (ADAM) Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Group. Ann. Intern. Med. 1997;126:441–449. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-126-6-199703150-00004[↩]

- Management of Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms. N Engl J Med 2021; 385:1690-1698 https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMcp2108504[↩][↩][↩]

- Shaw PM, Loree J, Gibbons RC. Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm. [Updated 2021 Jan 3]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470237[↩][↩][↩]

- Summers KL, Kerut EK, Sheahan CM, Sheahan MG 3rd. Evaluating the prevalence of abdominal aortic aneurysms in the United States through a national screening database. J Vasc Surg. 2021 Jan;73(1):61-68. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2020.03.046[↩][↩]

- Chaikof EL, Dalman RL, Eskandari MK, Jackson BM, Lee WA, Mansour MA, Mastracci TM, Mell M, Murad MH, Nguyen LL, Oderich GS, Patel MS, Schermerhorn ML, Starnes BW. The Society for Vascular Surgery practice guidelines on the care of patients with an abdominal aortic aneurysm. J Vasc Surg. 2018 Jan;67(1):2-77.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2017.10.044[↩][↩]

- Chan WK, Yong E, Hong Q, Zhang L, Lingam P, Tan GWL, Chandrasekar S, Lo ZJ. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the prevalence of abdominal aortic aneurysm in Asian populations. J Vasc Surg. 2021 Mar;73(3):1069-1074.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2020.08.140[↩]

- Li X., Zhao G., Zhang J., Duan Z., Xin S. Prevalence and Trends of the Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms Epidemic in General Population—A Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e81260. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081260[↩]

- Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm. https://vascular.org/patients-and-referring-physicians/conditions/abdominal-aortic-aneurysm[↩]

- Hultgren R., Granath F., Swedenborg J. Different Disease Profiles for Women and Men with Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2007;33:556–560. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2006.11.030[↩]

- Ashton H.A., Gao L., Kim L., Druce P.S., Thompson S.G., Scott R.A.P. Fifteen-year follow-up of a randomized clinical trial of ultrasonographic screening for abdominal aortic aneurysms. Br. J. Surg. 2007;94:696–701. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5780[↩]

- Lederle FA, Johnson GR, Wilson SE, Chute EP, Littooy FN, Bandyk D, Krupski WC, Barone GW, Acher CW, Ballard DJ. Prevalence and associations of abdominal aortic aneurysm detected through screening. Aneurysm Detection and Management (ADAM) Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Group. Ann Intern Med. 1997 Mar 15;126(6):441-9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-126-6-199703150-00004[↩][↩]

- Assar AN, Zarins CK. Ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm: a surgical emergency with many clinical presentations. Postgraduate Medical Journal 2009;85:268-273. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/pgmj.2008.074666[↩][↩]

- Bengtsson H, Bergqvist D, Ekberg O, Janzon L. A population based screening of abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAA). Eur J Vasc Surg. 1991 Feb;5(1):53-7. doi: 10.1016/s0950-821x(05)80927-2[↩]

- Ulug P, Powell JT, Martinez MA, Ballard DJ, Filardo G. Surgery for small asymptomatic abdominal aortic aneurysms. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020 Jul 1;7(7):CD001835. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001835.pub5[↩][↩][↩]

- Chaikof EL, Brewster DC, Dalman RL, Makaroun MS, Illig KA, Sicard GA, Timaran CH, Upchurch GR Jr, Veith FJ. SVS practice guidelines for the care of patients with an abdominal aortic aneurysm: executive summary. J Vasc Surg. 2009 Oct;50(4):880-96. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2009.07.001[↩]

- Aggarwal, S., Qamar, A., Sharma, V., & Sharma, A. (2011). Abdominal aortic aneurysm: A comprehensive review. Experimental and clinical cardiology, 16(1), 11–15. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3076160[↩][↩]

- Lederle FA, Johnson GR, Wilson SE, Ballard DJ, Jordan WD Jr, Blebea J, Littooy FN, Freischlag JA, Bandyk D, Rapp JH, Salam AA; Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study #417 Investigators. Rupture rate of large abdominal aortic aneurysms in patients refusing or unfit for elective repair. JAMA. 2002 Jun 12;287(22):2968-72. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.22.2968[↩]

- Nevitt MP, Ballard DJ, Hallett JW Jr. Prognosis of abdominal aortic aneurysms. A population-based study. N Engl J Med. 1989 Oct 12;321(15):1009-14. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198910123211504[↩]

- Brewster DC, Cronenwett JL, Hallett JW Jr, Johnston KW, Krupski WC, Matsumura JS; Joint Council of the American Association for Vascular Surgery and Society for Vascular Surgery. Guidelines for the treatment of abdominal aortic aneurysms. Report of a subcommittee of the Joint Council of the American Association for Vascular Surgery and Society for Vascular Surgery. J Vasc Surg. 2003 May;37(5):1106-17. doi: 10.1067/mva.2003.363[↩]

- Gadowski GR, Pilcher DB, Ricci MA. Abdominal aortic aneurysm expansion rate: effect of size and beta-adrenergic blockade. J Vasc Surg. 1994 Apr;19(4):727-31. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(94)70048-6[↩][↩]

- Hirsch AT, Haskal ZJ, Hertzer NR, et al. ACC/AHA 2005 Practice Guidelines for the management of patients with peripheral arterial disease (lower extremity, renal, mesenteric, and abdominal aortic): A collaborative report from the American Association for Vascular Surgery/Society for Vascular Surgery, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society for Vascular Medicine and Biology, Society of Interventional Radiology, and the ACC/AHA Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Develop Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Peripheral Arterial Disease): Endorsed by the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; Society for Vascular Nursing; Trans-Atlantic Inter-Society Consensus; and Vascular Disease Foundation. Circulation. 2006;113:e463–e654. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.174526[↩][↩][↩]

- Brady AR, Thompson SG, Fowkes FG, Greenhalgh RM, Powell JT; UK Small Aneurysm Trial Participants. Abdominal aortic aneurysm expansion: risk factors and time intervals for surveillance. Circulation. 2004 Jul 6;110(1):16-21. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000133279.07468.9F[↩]

- Brewster DC, Cronenwett JL, Hallett JW Jr, Johnston KW, Krupski WC, Matsumura JS; Joint Council of the American Association for Vascular Surgery and Society for Vascular Surgery. Guidelines for the treatment of abdominal aortic aneurysms. Report of a subcommittee of the Joint Council of the American Association for Vascular Surgery and Society for Vascular Surgery. J Vasc Surg. 2003 May;37(5):1106-17. https://doi.org/10.1067/mva.2003.363[↩]

- Chaikof EL, Dalman RL, Eskandari MK, Jackson BM, Lee WA, Mansour MA, Mastracci TM, Mell M, Murad MH, Nguyen LL, Oderich GS, Patel MS, Schermerhorn ML, Starnes BW. The Society for Vascular Surgery practice guidelines on the care of patients with an abdominal aortic aneurysm. J Vasc Surg. 2018 Jan;67(1):2-77.e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2017.10.044[↩]

- Abdominal aortic aneurysm. https://radiopaedia.org/articles/abdominal-aortic-aneurysm?lang=us[↩][↩]

- Schermerhorn M. A 66-year-old man with an abdominal aortic aneurysm: review of screening and treatment. JAMA. 2009 Nov 11;302(18):2015-22. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1502[↩]

- Harris LM, Faggioli GL, Fiedler R, Curl GR, Ricotta JJ. Ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms: factors affecting mortality rates. J Vasc Surg. 1991 Dec;14(6):812-8; discussion 819-20. doi: 10.1067/mva.1991.33494[↩]

- Abdominal aortic aneurysm rupture. https://radiopaedia.org/articles/abdominal-aortic-aneurysm-rupture-2?lang=us[↩][↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Lech C., Swaminathan A. Abdominal Aortic Emergencies. Emerg. Med. Clin. North Am. 2017;35:847–867. doi: 10.1016/j.emc.2017.07.003[↩]

- Azhar B., Patel S.R., Holt P.J., Hinchliffe R.J., Thompson M.M., Karthikesalingam A. Misdiagnosis of Ruptured Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Endovasc. Ther. 2014;21:568–575. doi: 10.1583/13-4626MR.1[↩]

- Jeanmonod D, Yelamanchili VS, Jeanmonod R. Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Rupture. [Updated 2021 Aug 11]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459176[↩]

- Assar A.N., Zarins C.K. Ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm: A surgical emergency with many clinical presentations. Postgrad. Med, J. 2009;85:268–273. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2008.074666[↩][↩]

- Biancari F., Paone R., Venermo M., D’Andrea V., Perälä J. Diagnostic Accuracy of Computed Tomography in Patients with Suspected Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Rupture. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2013;45:227–230. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2012.12.006[↩]

- Acher C., Ramirez M.C.C., Wynn M. Operative Mortality and Morbidity in Ruptured Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms in the Endovascular Age. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2020;66:70–76. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2019.10.073[↩][↩][↩]

- IMPROVE Trial Investigators Comparative clinical effectiveness and cost effectiveness of endovascular strategy v open repair for ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm: Three year results of the IMPROVE randomised trial. BMJ. 2017;359:j4859. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j4859[↩]

- D’Oria M., Hanson K.T., Shermerhorn M., Bower T.C., Mendes B.C., Shuja F., Oderich G.S., DeMartino R.R. Editor’s Choice—Short Term and Long Term Outcomes After Endovascular or Open Repair for Ruptured Infrarenal Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms in the Vascular Quality Initiative. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2020;59:703–716. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2019.12.032[↩]

- Kontopodis N., Galanakis N., Antoniou S.A., Tsetis D., Ioannou C.V., Veith F.J., Powell J.T., Antoniou G.A. Meta-Analysis and Meta-Regression Analysis of Outcomes of Endovascular and Open Repair for Ruptured Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2020;59:399–410. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2019.12.023[↩]

- Varkevisser R.R., Swerdlow N.J., de Guerre L.E., Dansey K., Stangenberg L., Giles K.A., Verhagen H.J., Schermerhorn M.L. Society for Vascular Surgery Vascular Quality Initiative Five-Year Survival Following Endovascular Repair of Ruptured Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms Is Improving. J. Vasc. Surg. 2020;72:105–113.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2019.10.074[↩]

- Kontopodis N., Tavlas E., Ioannou C.V., Giannoukas A.D., Geroulakos G., Antoniou G.A. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Outcomes of Open and Endovascular Repair of Ruptured Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm in Patients with Hostile vs. Friendly Aortic Anatomy. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2020;59:717–728. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2019.12.024[↩]

- Lederle FA, Johnson GR, Wilson SE, Chute EP, Hye RJ, Makaroun MS, Barone GW, Bandyk D, Moneta GL, Makhoul RG. The aneurysm detection and management study screening program: validation cohort and final results. Aneurysm Detection and Management Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Investigators. Arch Intern Med. 2000 May 22;160(10):1425-30. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.10.1425[↩]

- Emile R Mohler III. Epidemiology, risk factors, pathogenesis and natural history of abdominal aortic aneurysm. UpToDate. Waltham, MA: UpToDate; February, 2014[↩][↩][↩]

- Ada Hamosh. AORTIC ANEURYSM, FAMILIAL ABDOMINAL, 1; AAA1. OMIM. https://omim.org/entry/100070[↩]

- Zommorodi S, Leander K, Roy J, Steuer J, Hultgren R. Understanding abdominal aortic aneurysm epidemiology: socioeconomic position affects outcome. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2018 Oct;72(10):904-910. doi: 10.1136/jech-2018-210644[↩]

- Xu C, Zarins CK, Glagov S. Aneurysmal and occlusive atherosclerosis of the human abdominal aorta. J Vasc Surg. 2001 Jan;33(1):91-6. doi: 10.1067/mva.2001.109744[↩]

- Dobrin PB, Baumgartner N, Anidjar S, Chejfec G, Mrkvicka R. Inflammatory aspects of experimental aneurysms. Effect of methylprednisolone and cyclosporine. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1996 Nov 18;800:74-88. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1996.tb33300.x[↩]

- Parry DJ, Al-Barjas HS, Chappell L, Rashid ST, Ariëns RA, Scott DJ. Markers of inflammation in men with small abdominal aortic aneurysm. J Vasc Surg. 2010 Jul;52(1):145-51. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2010.02.279[↩]

- Jiang H, Sasaki T, Jin E, Kuzuya M, Cheng XW. Inflammatory Cells and Proteases in Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm and its Complications. Curr Drug Targets. 2018;19(11):1289-1296. doi: 10.2174/1389450119666180531103458[↩]

- Wanhainen A, Verzini F, Van Herzeele I, Allaire E, Bown M, Cohnert T, Dick F, van Herwaarden J, Karkos C, Koelemay M, Kölbel T, Loftus I, Mani K, Melissano G, Powell J, Szeberin Z, Esvs Guidelines Committee, de Borst GJ, Chakfe N, Debus S, Hinchliffe R, Kakkos S, Koncar I, Kolh P, Lindholt JS, de Vega M, Vermassen F, Document Reviewers, Björck M, Cheng S, Dalman R, Davidovic L, Donas K, Earnshaw J, Eckstein HH, Golledge J, Haulon S, Mastracci T, Naylor R, Ricco JB, Verhagen H. Editor’s Choice – European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS) 2019 Clinical Practice Guidelines on the Management of Abdominal Aorto-iliac Artery Aneurysms. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2019 Jan;57(1):8-93. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2018.09.020 Erratum in: Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2020 Mar;59(3):494.[↩][↩]

- Wilmink AB, Forshaw M, Quick CR, Hubbard CS, Day NE. Accuracy of serial screening for abdominal aortic aneurysms by ultrasound. J Med Screen. 2002;9(3):125-7. doi: 10.1136/jms.9.3.125[↩]

- Rubano E., Mehta N., Caputo W., Paladino L., Sinert R. Systematic Review: Emergency Department Bedside Ultrasonography for Diagnosing Suspected Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2013;20:128–138. doi: 10.1111/acem.12080[↩]

- Meecham L., Evans R., Buxton P., Allingham K., Hughes M., Rajagopalan S., Fairhead J., Asquith J., Pherwani A. Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Diameters: A Study on the Discrepancy between Inner to Inner and Outer to Outer Measurements. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2015;49:28–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2014.10.002[↩]

- Hallett R.L., Ullery B.W., Fleischmann D. Abdominal aortic aneurysms: Pre- and post-procedural imaging. Abdom. Radiol. 2018;43:1044–1066. doi: 10.1007/s00261-018-1520-5[↩]

- Kumar Y., Hooda K., Li S., Goyal P., Gupta N., Adeb M. Abdominal aortic aneurysm: Pictorial review of common appearances and complications. Ann. Transl. Med. 2017;5:256. doi: 10.21037/atm.2017.04.32[↩]

- Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm: Screening. Final Recommendation Statement, December 10, 2019. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/abdominal-aortic-aneurysm-screening[↩][↩]

- Abdominal aortic aneurysm. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/abdominal-aortic-aneurysm/diagnosis-treatment/drc-20350693[↩]

- Chaikof E.L., Dalman R.L., Eskandari M.K., Jackson B.M., Lee W.A., Mansour M.A., Mastracci T.M., Mell M., Murad M.H., Nguyen L.L., et al. The Society for Vascular Surgery practice guidelines on the care of patients with an abdominal aortic aneurysm. J. Vasc. Surg. 2018;67:2–77.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2017.10.044[↩]

- Wanhainen A., Verzini F., Van Herzeele I., Allaire E., Bown M., Cohnert T., Dick F., van Herwaarden J., Karkos C., Koelemay M., et al. Editor’s Choice—European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS) 2019 Clinical Practice Guidelines on the Management of Abdominal Aorto-iliac Artery Aneurysms. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2019;57:8–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2018.09.020[↩]

- Leemans E., Willems T.P., Van Der Laan M.J., Slump C.H., Zeebregts C.J. Biomechanical Indices for Rupture Risk Estimation in Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms. J. Endovasc. Ther. 2016;24:254–261. doi: 10.1177/1526602816680088[↩]

- RESCAN Collaborators. Bown M.J., Sweeting M.J., Brown L.C., Powell J.T., Thompson S.G. Surveillance Intervals for Small Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms: A Meta-Analysis. JAMA. 2013;309:806–813. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2013.04.019[↩]

- Amin S, Schnabel J, Eldergash O, Chavan A. Endovaskuläre Aneurysmaversorgung (EVAR) : Komplikationsmanagement [Endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR) : Complication management]. Radiologe. 2018 Sep;58(9):841-849. German. doi: 10.1007/s00117-018-0437-x[↩]

- Powell JT, Sweeting MJ, Brown LC, Gotensparre SM, Fowkes FG, Thompson SG. Systematic review and meta-analysis of growth rates of small abdominal aortic aneurysms. Br J Surg. 2011 May;98(5):609-18. doi: 10.1002/bjs.7465[↩]

- Sharp MA, Collin J. A myth exposed: fast growth in diameter does not justify precocious abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2003 May;25(5):408-11. doi: 10.1053/ejvs.2002.1850[↩]

- Sweeting MJ, Thompson SG, Brown LC, Powell JT; RESCAN collaborators. Meta-analysis of individual patient data to examine factors affecting growth and rupture of small abdominal aortic aneurysms. Br J Surg. 2012 May;99(5):655-65. doi: 10.1002/bjs.8707[↩]

- S Vammen, J S Lindholt, L Østergaard, H Fasting, E W Henneberg, Randomized double-blind controlled trial of roxithromycin for prevention of abdominal aortic aneurysm expansion, British Journal of Surgery, Volume 88, Issue 8, August 2001, Pages 1066–1072, https://doi.org/10.1046/j.0007-1323.2001.01845.x[↩]

- ((Velicer CM, Heckbert SR, Lampe JW, Potter JD, Robertson CA, Taplin SH. Antibiotic use in relation to the risk of breast cancer. JAMA. 2004 Feb 18;291(7):827-35. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.7.827[↩]

- Mortality results for randomised controlled trial of early elective surgery or ultrasonographic surveillance for small abdominal aortic aneurysms. The UK Small Aneurysm Trial Participants. Lancet. 1998 Nov 21;352(9141):1649-55.[↩]