Alcoholism

Alcoholism is also known as alcohol dependence, alcohol addiction, severe alcohol use disorder, severe alcohol abuse or severe alcohol dependence syndrome, is a chronic, relapsing brain disease where a person has lost control of their alcohol use, and they continue to drink despite adverse social, occupational, or health consequences 1, 2. Alcoholism is a chronic disease. That means that it lasts for a long time, or it causes problems again and again. The main treatment for alcoholism is to stop drinking alcohol, which can be difficult. This is because when you use alcohol, parts of your brain make you feel pleasure and intoxication. Most people who are alcoholics still feel a strong desire for alcohol even after they stop drinking.

Alcoholism or ‘alcohol dependence’ is characterized by craving, tolerance, a preoccupation with alcohol and continued drinking in spite of harmful consequences (e.g, liver disease or depression caused by drinking). The International Classification of Diseases volume 10 (ICD-10) defines dependency as: “a cluster of behavioral, cognitive, and physiological phenomena that develop after repeated substance use and that typically include a strong desire to take the drug, difficulties in controlling its use, persisting in its use despite harmful consequences, a higher priority given to drug use than to other activities and obligations, increased tolerance, and sometimes a physical withdrawal state”.

Alcoholism or alcohol dependence, is a disease that causes:

- Craving – a strong need to drink

- Loss of control – not being able to stop drinking once you’ve started

- Physical dependence – withdrawal symptoms

- Tolerance – the need to drink more alcohol to feel the same effect

- Adverse social, occupational or health consequences – the alcohol you are drinking affects your life, your relationships or the lives of others. Alcohol dependence is also associated with increased criminal activity and domestic violence, and an increased rate of significant mental and physical disorders

Griffith Edwards and Gross 3 defined some simple markers of alcoholism. These markers are:

- dependent drinkers have a narrow repertoire of alcohol consumption: alcohol is used to avoid withdrawal symptoms

- drinking overtakes the individual’s activities to the exclusion of everything else, leading to theft, begging and borrowing

- withdrawal symptoms include trembling, fear, insomnia, nightmares, sweating and hallucinations.

- tolerance develops so that the dependent drinker consumes quantities which might make non-drinkers unconscious

- dependent drinkers know that they cannot control their alcohol use

- there is a high tendency to relapse after abstinence

- alcohol withdrawal symptoms occur within 12 hours of the last drink.

The American Psychiatric Association has outlined the criteria used by doctors to diagnose substance use disorders such as alcoholism 4. To receive an alcohol use disorder diagnosis, a person must meet at least 2 of the following criteria within a 12-month period; however, only a qualified mental health professional or a physician can diagnose alcohol use disorder 4:

- Drinking more than you originally intended.

- Being unable to cut down alcohol use even if you want to.

- Spending a lot of time obtaining, using, and recovering from the effects of alcohol.

- Strong desires or cravings to drink alcohol.

- Failing to fulfill obligations at work, home, or school due to alcohol use.

- Continuing to drink despite developing interpersonal/social problems that are the consequence of your alcohol use.

- Giving up activities you once enjoyed because of alcohol use.

- Drinking in situations where it is physically dangerous to do so (like driving or operating machinery).

- Continuing to drink despite a persistent or recurring physical or mental health condition that is likely worsened or caused by your alcohol use.

- Tolerance, meaning you need to drink more to achieve previous effects.

- Withdrawal symptoms (like tremors, sweating, insomnia, or anxiety) when you stop drinking or significantly reduce your drinking (i.e., alcohol dependence).

You may have a drinking problem if you have at least 2 of the following characteristics:

- There are times when you drink more or longer than you planned to.

- You have not been able to cut down or stop drinking on your own, even though you have tried or you want to.

- You spend a lot of time drinking, being sick from drinking, or getting over the effects of drinking.

- Your urge to drink is so strong, you cannot think about anything else.

- As a result of drinking, you do not do what you are expected to do at home, work, or school. Or, you keep getting sick because of drinking.

- You continue to drink, even though alcohol is causing problems with your family or friends.

- You spend less time on or no longer take part in activities that used to be important or that you enjoyed. Instead, you use that time to drink.

- Your drinking has led to situations that you or someone else could have been injured, such as driving while drunk or having unsafe sex.

- Your drinking makes you anxious, depressed, forgetful, or causes other health problems, but you keep drinking.

- You need to drink more than you did to get the same effect from alcohol. Or, the number of drinks you are used to having now have less effect than before.

- When the effects of alcohol wear off, you have symptoms of withdrawal. These include, tremors, sweating, nausea, or insomnia. You may even have had a seizure or hallucinations (sensing things that are not there).

Alcohol use disorder is diagnosed when a person answers “yes” to two or more of the questions below.

In the past year, have you:

- Ended up drinking more or for a longer time than you had planned to?

- Wanted to cut down or stop drinking, or tried to, but couldn’t?

- Spent a lot of your time drinking, or recovering from drinking?

- Needed a drink first thing in the morning to steady your nerves or get rid of a hangover?

- Felt a strong need to drink?

- Felt annoyed by criticism of your drinking?

- Had guilty feelings about drinking?

- Found that drinking – or being sick from drinking – often interfered with your family life, job, or school?

- Kept drinking even though it was causing trouble with your family or friends?

- Given up or cut back on activities that you enjoyed just so you could drink?

- Gotten into dangerous situations while drinking or after drinking? Some examples are driving drunk and having unsafe sex.

- Kept drinking even though it was making you feel depressed or anxious? Or when it was adding to another health problem?

- Had to drink more and more to feel the effects of the alcohol?

- Had withdrawal symptoms when the alcohol was wearing off? They include trouble sleeping, shakiness, irritability, anxiety, depression, restlessness, nausea, and sweating. In severe cases, you could have a fever, seizures, or hallucinations.

If you have any of these symptoms, your drinking may already be a cause for concern. The more symptoms you have, the more urgent the need for change. A health professional can conduct a formal assessment of your symptoms to see if alcohol use disorder is present.

Like many other diseases, alcoholism affects you physically and mentally. Both your body and your mind have to be treated. In addition to medicine, your doctor may recommend psychosocial treatments. These treatments can help you change your behavior and cope with your problems without using alcohol. Examples of psychosocial treatments include:

- Alcoholics Anonymous or other support group meetings

- Counseling

- Family therapy

- Group therapy

- Addiction treatment program

- Hospital treatment

There may be special centers in your area that offer this kind of treatment. Your doctor can refer you to the psychosocial treatment that is right for you.

Recovering people who attend support groups regularly do better than those who do not. Groups can vary widely, so shop around for one that’s comfortable. You’ll get more out of it if you become actively involved by having a sponsor and reaching out to other members for assistance.

- Alcoholics Anonymous (https://www.aa.org)

- Moderation Management (https://moderation.org)

- Secular Organizations for Sobriety (https://www.sossobriety.org)

- SMART Recovery (https://www.smartrecovery.org)

- Women for Sobriety (https://womenforsobriety.org)

- Al-Anon Family Groups (https://al-anon.org)

- Adult Children of Alcoholics (https://adultchildren.org)

- National Council on Alcoholism and Drug Dependence (https://recovered.org)

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (https://www.niaaa.nih.gov)

- National Organization on Fetal Alcohol Syndrome (https://fasdunited.org)

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (https://findtreatment.gov)

If you feel that you sometimes drink too much alcohol, or your drinking is causing problems, or your family is concerned about your drinking, talk with your doctor. Other ways to get help include talking with a mental health professional or seeking help from a support group such as Alcoholics Anonymous or a similar type of self-help group.

Because denial is common, you may not feel like you have a problem with drinking. You might not recognize how much you drink or how many problems in your life are related to alcohol use. Listen to relatives, friends or co-workers when they ask you to examine your drinking habits or to seek help. Consider talking with someone who has had a problem drinking, but has stopped.

If your loved one needs help

Many people with alcohol use disorder hesitate to get treatment because they don’t recognize they have a problem. An intervention from loved ones can help some people recognize and accept that they need professional help. If you’re concerned about someone who drinks too much, ask a professional experienced in alcohol treatment for advice on how to approach that person.

Types of alcohol

Alcohol in the form of ethanol (ethyl alcohol) is found in alcoholic beverages, mouthwash, cooking extracts, some medications and certain household products. Other forms of alcohol — including isopropyl alcohol (found in rubbing alcohol, lotions and some cleaning products) and methanol or ethylene glycol (a common ingredient in antifreeze, paints and solvents) — can cause other types of toxic poisoning that require emergency treatment. Ethanol (alcohol) is a central nervous system depressant that produces euphoria and behavioral excitation at low blood concentrations and acute intoxication (drowsiness, ataxia, slurred speech, stupor, and coma) at higher concentrations. The short-term effects of alcohol result from its actions on ligand-gated and voltage-gated ion channels 5. Prolonged alcohol consumption leads to the development of tolerance and physical dependence, which may result from compensatory functional changes in the same ion channels. Abrupt cessation of prolonged alcohol consumption unmasks these changes, leading to the alcohol withdrawal syndrome, which includes blackouts, tremors, muscular rigidity, delirium tremens, and seizures 6. Alcohol withdrawal seizures typically occur 6 to 48 hours after discontinuation of alcohol consumption and are usually generalized tonic–clonic seizures, although partial seizures also occur 7.

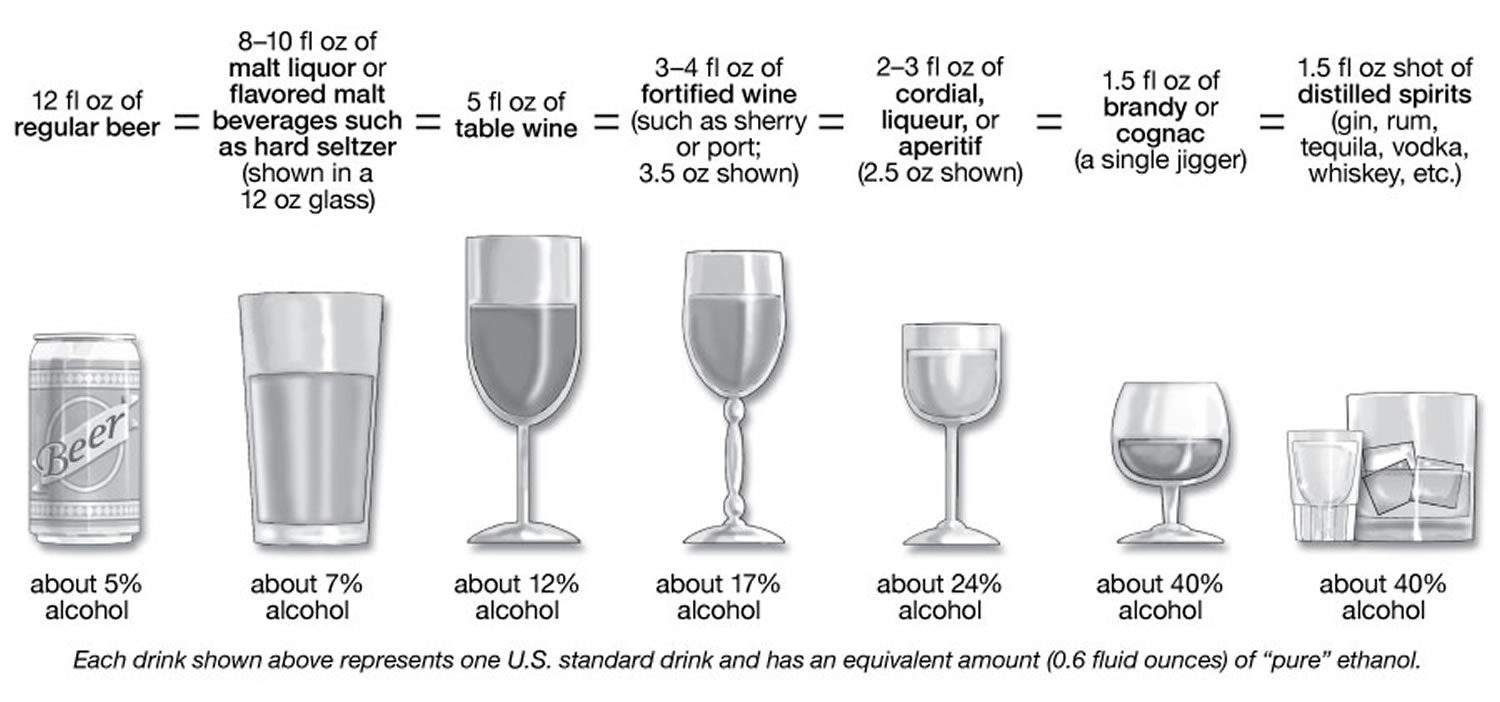

In the United States, a “standard drink” or “alcoholic drink equivalent” is any drink containing 14 grams, or about 0.6 fluid ounces, of “pure” ethanol. One alcoholic drink equals one 12-ounce (oz), or 355 milliliters (mL), can or bottle of beer (with 5% alcohol by volume or alc/vol), a 5-ounce (148 mL) glass of wine (with 12% alc/vol), 1 wine cooler, 1 cocktail, 1 shot of hard liquor; or 1.5 ounces of 80-proof distilled spirits (such as whiskey, rum, or tequila) (with 40% alc/vol) 8. While there is no guaranteed safe amount of alcohol for anyone, the answer from current research is, the less alcohol, the better 9, 10. Alcohol is a carcinogen associated with cancer of the oral cavity, pharynx, larynx, esophagus, colon, rectum, liver, and female breast, with breast cancer risk rising with less than one drink a day. Your whole body is impacted by alcohol use not just your liver, but also your brain, gut, pancreas, lungs, cardiovascular system, immune system, and more and may explain, for example, challenges in managing hypertension, atrial fibrillation, diabetes, and recurrent lung infections.

Alcohol contributes to more than 200 health conditions including liver cirrhosis, cancers, and injuries and causes more than 3 million deaths each year globally (5.3% of all deaths worldwide) 11, 12. In the U.S., about 99,000 people die every year from alcohol-related causes 13, making alcohol one of the leading causes of preventable death 14, 15. More than half of the deaths result from chronic heavy alcohol consumption while the remainder result from acute injuries sustained while intoxicated 16.

The health risks of alcohol tend to be dose-dependent, and the likelihood of certain harms, such as cancer, begin at relatively low amounts 17. Even drinking within the U.S. Dietary Guidelines (see drinking level terms below), for example, increases the risk of breast cancer 18, 19. Additionally, earlier research suggested cardiovascular benefits, but newer, more rigorous studies are finding little or no protective effect of alcohol on cardiovascular or other outcomes 20, 21, 22, 23. In short, current research indicates there is no safe drinking level,11 underscoring the message to patients that “the less, the better” when it comes to alcohol.

The 2020-2025 U.S. Dietary Guidelines states that for adults who choose to drink alcohol, women should have 1 drink or less in a day and men should have 2 drinks or less in a day 24. These amounts are not intended as an average but rather a daily limit.

You are abusing alcohol when:

- You drink 7 drinks per week or more than 3 drinks per occasion (for women).

- You drink more than 14 drinks per week or more than 4 drinks per occasion (for men).

- You have more than 7 drinks per week or more than 3 drinks per occasion (for men and women older than 65).

- Consuming these amounts of alcohol harms your health, relationships, work, and/or causes legal problems.

Figure 1. Standard drink

Footnotes: The sample standard drinks above are just starting points for comparison, because actual alcohol content and customary serving sizes can vary greatly both across and within types of beverages. For example:

- Beer: The most popular type of beer is light beer, which may be light in calories, but not necessarily in alcohol. The mean alc/vol for light beers is 4.3%, almost as much as a regular beer with 5% alc/vol.4 On average, craft beers have more than 5% alc/vol and flavored malt beverages, such as hard seltzers, more than 6% alc/vol.4 Some craft beers and flavored malt beverages have in the range of 8-9% alc/vol. Advise patients to check container labels for the alcohol content and adjust their intake accordingly.

- Wine: The largest category of wine is table wine. On average, table wines contain about 12% alc/vol4 and can range from about 5% to 16%. Larger wine glasses can encourage larger pours. People are often unaware that a 25-ounce (750ml) bottle of table wine with 12% alc/vol contains five standard drinks, and one with 14% alc/vol holds nearly six.

- Cocktails: Recipes for cocktails often exceed one standard drink’s worth of alcohol. The cocktail content calculator on Rethinking Drinking shows the alcohol content in sample cocktails.

What is considered 1 drink?

The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism defines one standard drink as any one of these:

- 12 ounces (355 milliliters) of regular beer (about 5 percent alcohol)

- 8 to 9 ounces (237 to 266 milliliters) of malt liquor (about 7 percent alcohol)

- 5 ounces (148 milliliters) of unfortified wine (about 12 percent alcohol)

- 1.5 ounces (44 milliliters) of 80-proof hard liquor (about 40 percent alcohol)

Levels of alcohol use

There are four levels of alcohol use:

- Social drinking: There is no guaranteed safe amount of alcohol for anyone. According to the “Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2020-2025” 24, adults of legal drinking age can choose not to drink or to drink in moderation by limiting intake to 2 drinks or less in a day for men (less than 14 drinks per week for men) and 1 drink or less in a day for women (less than 7 drinks per week for women), when alcohol is consumed. Drinking less is better for health than drinking more.

- At risk consumption: the level of drinking begins to pose a health risk. Frequent heavy drinking raises the risk for both acute harms, such as falls and medication interactions, and for chronic consequences, such as alcohol use disorder and dose-dependent increases in liver disease, heart disease and cancers 25, 26, 27.

- For men, consuming more than 5 drinks on any day or more than 15 drinks per week

- For women, consuming more than 4 drinks on any day or more than 8 drinks per week

- Binge drinking on 5 or more days in the past month

- Heavy drinking thresholds for women are lower than men because after consumption, alcohol distributes itself evenly in body water, and pound for pound, women have proportionally less water in their bodies than men do. This means that after a woman and a man of the same weight drink the same amount of alcohol, the woman’s blood alcohol concentration (BAC) will tend to be higher, putting her at greater risk for harm.

- Problem drinking: drinking causes serious problems to you, your family, your work and society in general

- Alcohol dependence and addiction:

- periodic or chronic intoxication

- uncontrollable craving for drink when sober

- tolerance to the effects of alcohol

- psychological and/or physical dependence

What is binge drinking?

The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) defines binge drinking is drinking so much at once that your blood alcohol concentration (BAC) level is 0.08% (0.08 grams of alcohol per deciliter of blood) or more. For a man, this usually happens after having 5 or more drinks within about 2 hours. For a woman, it is after about 4 or more drinks within about 2 hours 28. Not everyone who binge drinks has an alcohol use disorder, but they are at higher risk for getting one.

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), which conducts the annual National Survey on Drug Use and Health, defines binge drinking as 5 or more alcoholic drinks for males or 4 or more alcoholic drinks for females on the same occasion (i.e., at the same time or within a couple of hours of each other) on at least 1 day in the past month.

Binge drinking occurs in the majority of adolescents who drink 29, in half of adults who drink 29 and in 1 in 10 adults over age 65 30 and is increasing among women 31, 32.

Binge drinking causes more than half of the alcohol-related deaths in the U.S. 29. Binge drinking increases the risk of falls, burns, car crashes, memory blackouts, medication interactions, assaults, drownings, and overdose deaths 29.

What is alcohol poisoning?

Alcohol (ethanol) poisoning also known as alcohol overdose is generally caused by binge drinking at high intensity or from drinking too many alcoholic beverages, especially in a short period of time. Such drinking can exceed the body’s physiologic capacity to process alcohol, causing the blood alcohol concentration to rise. Alcohol exerts its effects by several mechanisms. Alcohol binds directly to gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptors in the brain, causing sedation. Alcohol also directly affects cardiac, hepatic, and thyroid tissue. Very high levels of alcohol in the body can shutdown critical areas of the brain that control breathing, heart rate, and body temperature, resulting in death. Alcohol poisoning deaths affect people of all ages but are most common among middle-aged adults and men. The clinical signs and symptoms of an overdose of alcohol occurs when a person has a blood alcohol content sufficient to produce impairments that increase the risk of harm.

- Rapid binge drinking (which often happens on a bet or a dare) is especially dangerous because the victim can drink a fatal dose before losing consciousness.

Alcohol overdoses can range in severity, from minimal impairment with balance, decreased judgment and control, slurred speech, reduced muscle coordination, vomiting, and stupor (reduced level of consciousness and cognitive function) to coma and death 33. However, an individual’s response to alcohol is variable depending on many factors, including the amount and rate of alcohol consumption, health status, consumption of other drugs, age, gender, the amount of food eaten, even ethnicity and metabolic and functional tolerance of the drinker 34, 35.

A major cause of alcohol poisoning is binge drinking — a pattern of heavy drinking when a male rapidly consumes five or more alcoholic drinks within two hours, or a female downs at least four drinks within two hours. An alcohol binge can occur over hours or last up to several days.

You can consume a fatal dose before you pass out. Even when you’re unconscious or you’ve stopped drinking, alcohol continues to be released from your stomach and intestines into your bloodstream, and the level of alcohol in your body continues to rise.

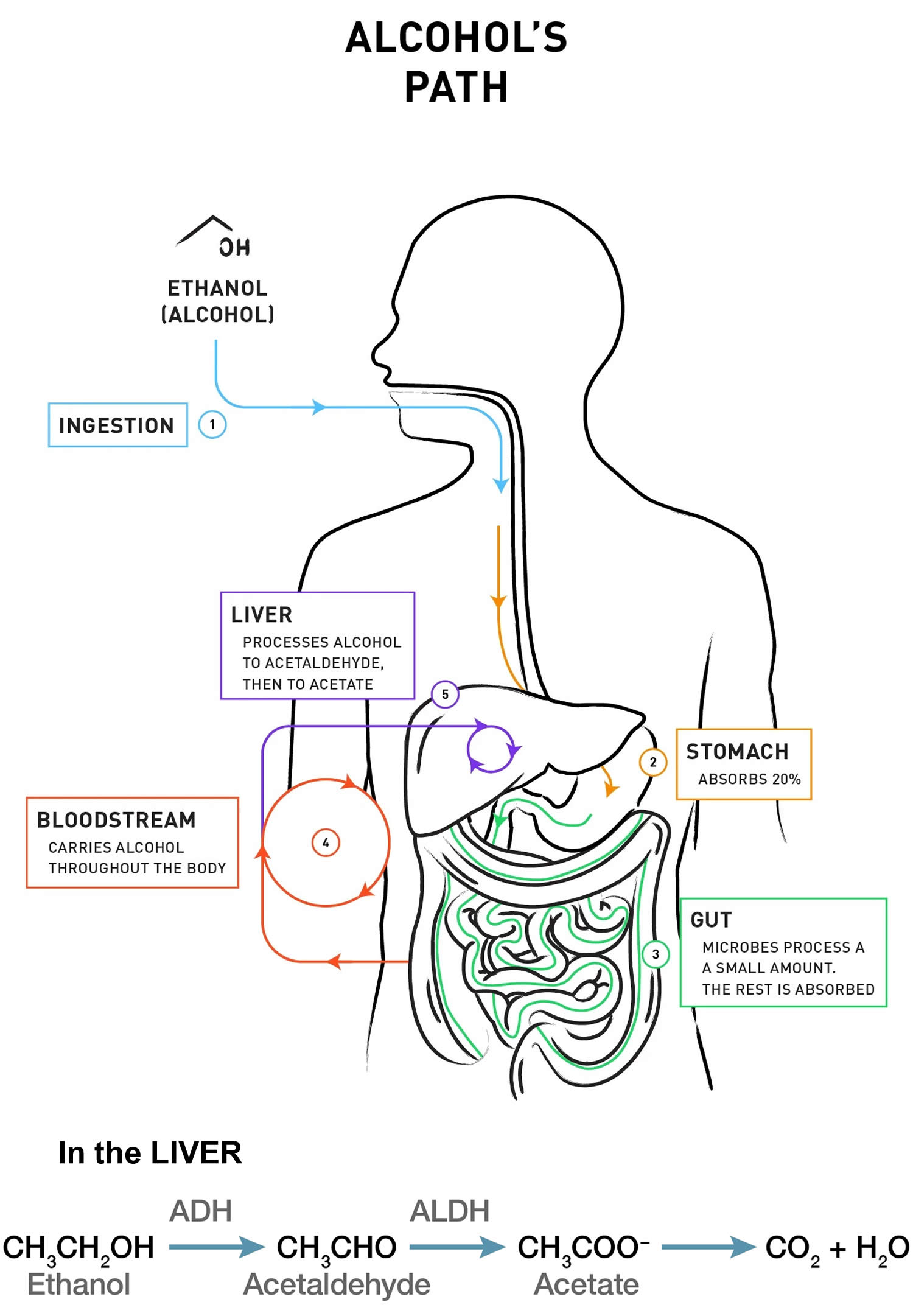

Alcohol is absorbed into the blood mainly from the small bowel, although some is absorbed from the stomach. Alcohol accumulates in blood because absorption is more rapid than oxidation and elimination. The concentration peaks about 30 to 90 min after ingestion if the stomach was previously empty 36.

About 5 to 10% of ingested alcohol is excreted unchanged in urine, sweat, and expired air; the remainder is metabolized mainly by the liver, where alcohol dehydrogenase converts ethanol to acetaldehyde. Acetaldehyde is ultimately oxidized to CO2 and water at a rate of 5 to 10 mL/hour (of absolute alcohol); each milliliter yields about 7 kcal. Alcohol dehydrogenase in the gastric mucosa accounts for some metabolism; much less gastric metabolism occurs in women.

In alcohol-naive people, a blood alcohol level of 300 to 400 mg/dL (BAC 0.3 to 0.4 percent) often causes unconsciousness, and a BAC ≥ 400 mg/dL may be fatal. Sudden death due to respiratory depression or arrhythmias may occur, especially when large quantities are drunk rapidly. This problem is emerging in US colleges but has been known in other countries where it is more common. Other common effects include hypotension and hypoglycemia.

The effect of a particular BAC varies widely; some chronic drinkers seem unaffected and appear to function normally with a BAC in the 300 to 400 mg/dL range, whereas nondrinkers and social drinkers are impaired at a BAC that is inconsequential in chronic drinkers.

- If you suspect someone has alcohol poisoning, get medical help immediately. If you or someone you are with has an exposure, call your local emergency number (such as 911) immediately. Cold showers, hot coffee, or walking will not reverse the effects of alcohol overdose and could actually make things worse.

- When in doubt, call for medical help.

- If you are having difficulty in determining whether an individual is acutely intoxicated, contact a health professional immediately – you cannot afford to guess.

- Hundreds of people die each year from acute alcohol intoxication, more commonly known as alcohol poisoning or alcohol overdose. Caused by drinking too much alcohol too fast, it often occurs on college campuses or wherever heavy drinking takes place.

- At the hospital, medical staff will manage any breathing problems, administer fluids to combat dehydration and low blood sugar, and flush the drinker’s stomach to help clear the body of toxins.

- The best way to avoid an alcohol overdose is to drink responsibly if you choose to drink.

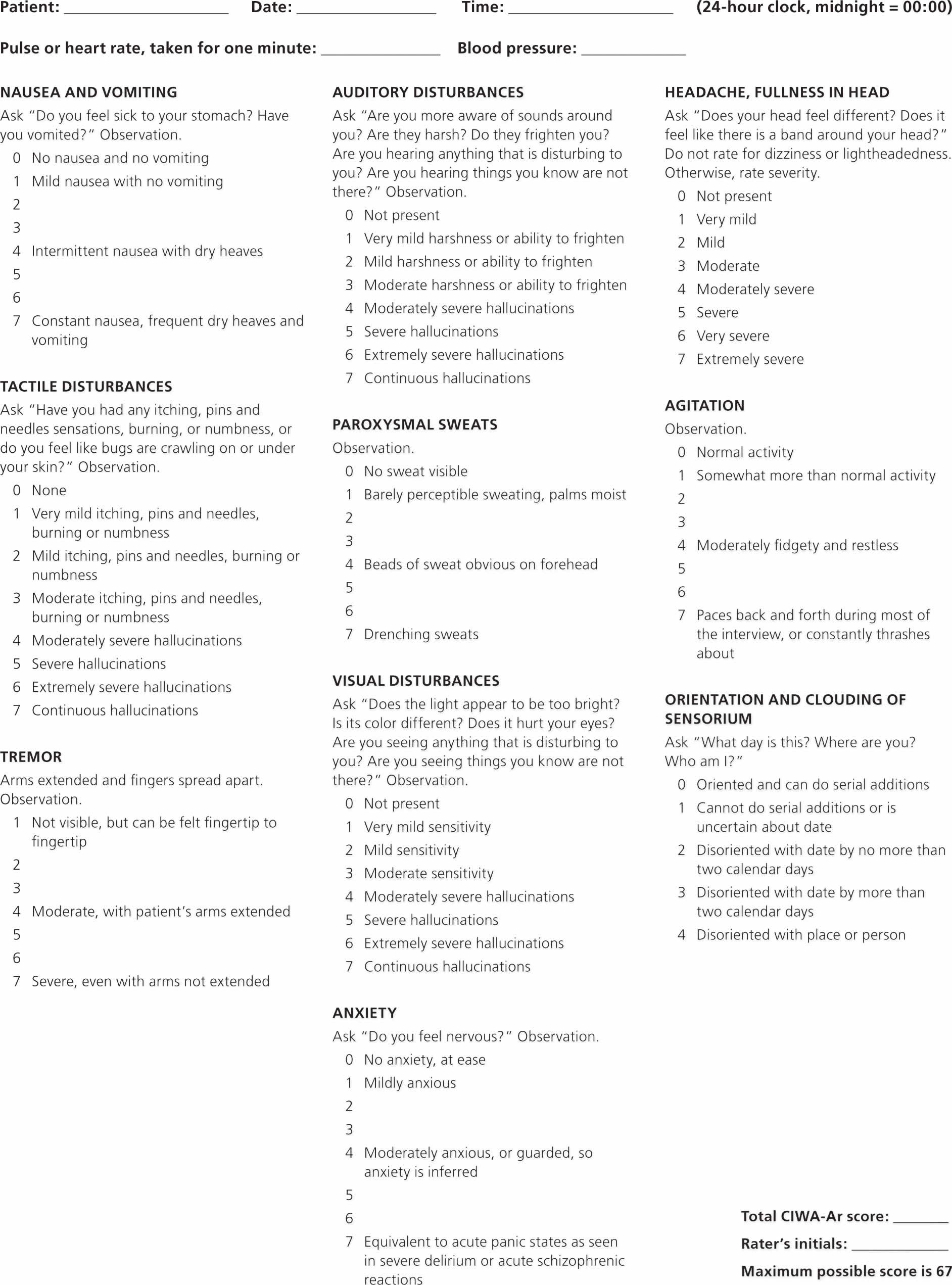

Figure 2. Alcohol Poisoning Scale

[Source 37 ]How does my body process alcohol?

When alcohol is consumed, it passes from your stomach and intestines into your bloodstream, where it distributes itself evenly throughout all the water in your body’s tissues and fluids. Drinking alcohol on an empty stomach increases the rate of absorption, resulting in higher blood alcohol level, compared to drinking on a full stomach. In either case, however, alcohol is still absorbed into the bloodstream at a much faster rate than it is metabolized. Thus, your blood alcohol concentration (BAC) builds when you have additional drinks before prior drinks are metabolized.

Your blood alcohol concentration (BAC) is largely determined by how much and how quickly you drink alcohol as well as by your body’s rates of alcohol absorption, distribution, and metabolism. Binge drinking is defined as reaching a BAC of 0.08% (0.08 grams of alcohol per deciliter of blood) or higher. A typical adult reaches this BAC after consuming 4 or more drinks (women) or 5 or more drinks (men), in about 2 hours.

Your body begins to metabolize alcohol within seconds after ingestion and proceeds at a steady rate, regardless of how much alcohol a person drinks or of attempts to sober up with caffeine or by other means. Most of the alcohol is broken down in your liver by the enzyme alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH). Alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) transforms ethanol, the type of alcohol in alcohol beverages, into acetaldehyde, a toxic, carcinogenic compound. Generally, acetaldehyde is quickly broken down to a less toxic compound, acetate, by acetaldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) (also called aldehyde dehydrogenase). Acetate then is broken down, mainly in tissues other than the liver, into carbon dioxide (CO2) and water (H2O), which are easily eliminated. To a lesser degree, other enzymes (CYP2E1 and catalase) also break down alcohol to acetaldehyde 38.

Although the rate of metabolism is steady in any given person, it varies widely among individuals depending on factors including liver size and body mass, as well as genetics. There are multiple ADH and ALDH enzymes that are encoded by different genes 38. These genetic variants have been shown to influence a person’s drinking levels and, consequently, the risk of developing alcohol abuse or dependence 39. Studies have shown that people carrying certain ADH and ALDH alleles (one of two or more variants of a gene) are at significantly reduced risk of becoming alcohol dependent. In fact, these associations are the strongest and most widely reproduced associations of any gene with the risk of alcoholism. Some people of Asian descent, for example, carry variations of the genes for alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) or acetaldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) that cause acetaldehyde (a toxic carcinogenic compound) to build up when alcohol is consumed, which in turn produces a flushing reaction and increases the risk of cancer risk 40, 41, 42. 20% of Chinese and Japanese cannot drink alcohol because of an inherited deficiency of acetaldehyde dehydrogenase 43.

Figure 3. How the body processes alcohol

Do you have a drinking problem?

While there is no guaranteed safe amount of alcohol for anyone, the answer from current research is, the less alcohol, the better 9, 10. The 2020-2025 U.S. Dietary Guidelines states that for adults who choose to drink alcohol, women should have 1 drink or less in a day and men should have 2 drinks or less in a day 24. These amounts are not intended as an average but rather a daily limit. Many people with alcohol problems cannot tell when their drinking is out of control. It is important to be aware of how much you are drinking. You should also know how your alcohol use may affect your life and those around you.

Many patients may think that heavy drinking is not a concern because they can “hold their liquor.” However, having an innate “low level of response” or “high tolerance” to alcohol is a reason for caution, as people with this trait tend to drink more and thus have an increased risk for alcohol-related problems including alcohol use disorder 44. People who drink within the U.S. Dietary Guidelines, too, may be unaware that even if they don’t feel a “buzz,” driving can be impaired 45.

Doctors consider your drinking medically unsafe when you drink:

- Many times a month, or even many times a week

- 3 to 4 drinks (or more) in 1 day

- 5 or more drinks on one occasion monthly, or even weekly

Twelve questions to ask if you think you may have a drinking problem

- Have you ever decided to stop drinking for a week or so, but only lasted for a couple of days? (Yes or No)

- Do you wish people would mind their own business about your drinking– stop telling you what to do? (Yes or No)

- Have you ever switched from one kind of drink to another in the hope that this would keep you from getting drunk? (Yes or No)

- Have you had to have a drink upon awakening during the past year? (Yes or No)

- Do you envy people who can drink without getting into trouble? (Yes or No)

- Have you had problems connected with drinking during the past year? (Yes or No)

- Has your drinking caused trouble at home? (Yes or No)

- Do you ever try to get “extra” drinks at a party because you do not get enough? (Yes or No)

- Do you tell yourself you can stop drinking any time you want to, even though you keep getting drunk when you don’t mean to? (Yes or No)

- Have you missed days of work or school because of drinking? (Yes or No)

- Do you have “blackouts”? (Yes or No) (Alcohol-related blackouts are gaps in a person’s memory for events that occurred while they were intoxicated. These gaps happen when a person drinks enough alcohol to temporarily block the transfer of memories from short-term to long-term storage, known as memory consolidation, in a brain area called the hippocampus.)

- Have you ever felt that your life would be better if you did not drink? (Yes or No)

If you answer YES 4 or more times – you are probably in trouble with alcohol.

However severe your drinking problem may seem, most people with alcohol use disorder can benefit from treatment. Unfortunately, less than 10 percent of them receive any treatment.

Ultimately, receiving treatment can improve your chances of success in overcoming alcohol use disorder.

Talk with your doctor to determine the best course of action for you.

What are the dangers of too much alcohol?

Too much alcohol is dangerous. Heavy drinking can increase the risk of certain cancers. It may lead to liver diseases, such as fatty liver disease and cirrhosis. It can also cause damage to the brain and other organs. Drinking during pregnancy can harm your baby. Alcohol also increases the risk of death from car crashes, injuries, homicide, and suicide.

How to stop drinking alcohol

There are many ways to help yourself stop drinking. You do not have to drink when other people drink. If someone gives you a drink, it is OK to say no. Stay away from people or places that make you drink. Do not keep alcohol at home.

Handling your urges to drink

Plan ahead to stay in control

As you change your drinking, it’s normal and common to have urges or a craving for alcohol. The words “urge” and “craving” refer to a broad range of thoughts, physical sensations, or emotions that tempt you to drink, even though you have at least some desire not to. You may feel an uncomfortable pull in two directions or sense a loss of control 46.

Fortunately, urges to drink are short-lived, predictable, and controllable. This short strategy offers a recognize-avoid-cope approach commonly used in cognitive behavioral therapy, which helps people to change unhelpful thinking patterns and reactions. It also provides worksheets to help you uncover the nature of your urges to drink and to make a plan for handling them.

With time, and by practicing new responses, you’ll find that your urges to drink will lose strength, and you’ll gain confidence in your ability to deal with urges that may still arise at times. If you are having a very difficult time with urges, or do not make progress with the strategies in this module after a few weeks, then consult a doctor or therapist for support. In addition, some new, non-habit forming medications can reduce the desire to drink or lessen the rewarding effect of drinking so it is easier to stop.

Recognize two types of “triggers”

An urge to drink can be set off by external triggers in the environment and internal ones within yourself.

- External triggers are people, places, things, or times of day that offer drinking opportunities or remind you of drinking. These “high-risk situations” are more obvious, predictable, and avoidable than internal triggers.

- Internal triggers can be puzzling because the urge to drink just seems to “pop up.” But if you pause to think about it when it happens, you’ll find that the urge may have been set off by a fleeting thought, a positive emotion such as excitement, a negative emotion such as frustration, or a physical sensation such as a headache, tension, or nervousness.

Consider tracking and analyzing your urges to drink for a couple of weeks. This will help you become more aware of when and how you experience urges, what triggers them, and ways to avoid or control them. A sample “urge to drink” tracking form is provided below.

Urge To Drink Tracker Form – Record the details as soon after an urge as possible.

| Date/time | Situation (people, place) or trigger (incident, feelings) | What was the urge like? | How I responded | What I’ll do next time | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Was it a thought? Emotion? Physical sensation? | Rate it from 1 (mild) to 10 (strong) | ||||

Footnote: You can Print a copy of this form and carry it with you from here: https://www.rethinkingdrinking.niaaa.nih.gov/Tools/Interactive-worksheets-and-more/Stay-in-control/Coping-With-Urges-To-Drink-urge-tracker.aspx

[Source: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Rethinking Drinking 47]Avoid high-risk situations

In many cases, your best strategy will be to avoid taking the chance that you’ll have an urge, then slip and drink. At home, keep little or no alcohol. Socially, avoid activities involving drinking. If you feel guilty about turning down an invitation, remind yourself that you are not necessarily talking about “forever.” When the urges subside or become more manageable, you may decide to ease gradually into some situations you now choose to avoid. In the meantime, you can stay connected with friends by suggesting alternate activities that don’t involve drinking.

Building your drink refusal skills

- Plan ahead to stay in control

Even if you are committed to changing your drinking, “social pressure” to drink from friends or others can make it hard to cut back or quit. This short module offers a recognize-avoid-cope approach commonly used in cognitive-behavioral therapy, which helps people to change unhelpful thinking patterns and reactions. It also provides links to worksheets to help you get started with your own plan to resist pressure to drink.

Recognize two types of pressure

The first step is to become aware of the two different types of social pressure to drink alcohol—direct and indirect.

- Direct social pressure is when someone offers you a drink or an opportunity to drink.

- Indirect social pressure is when you feel tempted to drink just by being around others who are drinking—even if no one offers you a drink.

Take a moment to think about situations where you feel direct or indirect pressure to drink or to drink too much. You can use the form below to write them down. Then, for each situation, choose some resistance strategies from below,or come up with your own. When you’re done, you can print the form or email it to yourself.

- Avoid pressure when possible

For some situations, your best strategy may be avoiding them altogether. If you feel guilty about avoiding an event or turning down an invitation, remind yourself that you are not necessarily talking about “forever.” When you have confidence in your resistance skills, you may decide to ease gradually into situations you now choose to avoid. In the meantime, you can stay connected with friends by suggesting alternate activities that don’t involve drinking.

Cope with situations you can’t avoid

- Know your “NO”

When you know alcohol will be served, it’s important to have some resistance strategies lined up in advance. If you expect to be offered a drink, you’ll need to be ready to deliver a convincing “no thanks.” Your goal is to be clear and firm, yet friendly and respectful. Avoid long explanations and vague excuses, as they tend to prolong the discussion and provide more of an opportunity to give in. Here are some other points to keep in mind:

- Don’t hesitate, as that will give you the chance to think of reasons to go along

- Look directly at the person and make eye contact

- Keep your response short, clear, and simple

The person offering you a drink may not know you are trying to cut down or stop, and his or her level of insistence may vary. It’s a good idea to plan a series of responses in case the person persists, from a simple refusal to a more assertive reply. Consider a sequence like this:

- No, thank you.

- No, thanks, I don’t want to.

- You know, I’m (cutting back/not drinking) now (to get healthier/to take care of myself/because my doctor said to). I’d really appreciate it if you’d help me out.

You can also try the “broken record” strategy. Each time the person makes a statement, you can simply repeat the same short, clear response. You might want to acknowledge some part of the person’s points (“I hear you…”) and then go back to your broken-record reply (“…but no thanks”). And if words fail, you can walk away.

- Script and practice your “NO”

Many people are surprised at how hard it can be to say no the first few times. You can build confidence by scripting and practicing your lines. First imagine the situation and the person who’s offering the drink. Then write both what the person will say and how you’ll respond, whether it’s a broken record strategy (mentioned above) or your own unique approach. Rehearse it aloud to get comfortable with your phrasing and delivery. Also, consider asking a supportive person to role-play with you, someone who would offer realistic pressure to drink and honest feedback about your responses. Whether you practice through made-up or real-world experiences, you’ll learn as you go. Keep at it, and your skills will grow over time.

- Try other strategies

In addition to being prepared with your “no thanks,” consider these strategies:

- Have non-alcoholic drinks always in hand if you’re quitting, or as “drink spacers” between drinks if you’re cutting back

- Keep track of every drink if you’re cutting back so you stay within your limits

- Ask for support from others to cope with temptation

- Plan an escape if the temptation gets too great

- Ask others to refrain from pressuring you or drinking in your presence (this can be hard)

If you have successfully refused drink offers before, then recall what worked and build on it.

Remember, it’s your choice

How you think about any decision to change can affect your success. Many people who decide to cut back or quit drinking think, “I am not allowed to drink,” as if an external authority were imposing rules on them. Thoughts like this can breed resentment and make it easier to give in. It’s important to challenge this kind of thinking by telling yourself that you are in charge, that you know how you want your life to be, and that you have decided to make a change.

Similarly, you may worry about how others will react or view you if you make a change. Again, challenge these thoughts by remembering that it’s your life and your choice, and that your decision should be respected.

Plan to resist pressure to drink

It’s not possible to avoid all high-risk situations or to block internal triggers, so you’ll need a range of strategies to handle urges to drink. Here are some options:

- Remind yourself of your reasons for making a change. Carry your top reasons on a wallet card or in an electronic message that you can access easily, such as a mobile phone notepad entry or a saved email.

- Talk it through with someone you trust. Have a trusted friend on standby for a phone call, or bring one along to high-risk situations.

- Distract yourself with a healthy, alternative activity. For different situations, come up with engaging short, mid-range, and longer options, like texting or calling someone, watching short online videos, lifting weights to music, showering, meditating, taking a walk, or doing a hobby.

- Challenge the thought that drives the urge. Stop it, analyze the error in it, and replace it. Example: “It couldn’t hurt to have one little drink. WAIT a minute—what am I thinking? One could hurt, as I’ve seen ‘just one’ lead to lots more. I am sticking with my choice not to drink.”

- Ride it out without giving in. Instead of fighting an urge, accept it as normal and temporary. As you ride it out, keep in mind that it will soon crest like an ocean wave and pass.

- Leave high-risk situations quickly and gracefully. It helps to plan your escape in advance.

How to cut down or to quit drinking alcohol

If you’re considering changing your drinking, you’ll need to decide whether to cut down or to quit. It’s a good idea to discuss different options with a doctor, a friend, or someone else you trust.

Quitting is strongly advised if you:

- Try cutting down but cannot stay within the limits you set.

- Have had an alcohol use disorder or now have symptoms.

- Have a physical or mental condition that is caused or worsened by drinking.

- Are taking a medication that interacts with alcohol.

- Are or may become pregnant.

If none of the conditions above apply to you, then talk with your doctor to determine whether you should cut down or quit based on factors such as:

- Family history of alcohol problems

- Your age

- Whether you’ve had drinking-related injuries

- Symptoms such as sleep disorders and sexual dysfunction

Planning for change

Even when you have committed to making a change, you still may have mixed feelings at times. Making a written “My Alcohol Change Plan” will help you to solidify your goals, why you want to reach them, and how you plan to do it.

A sample format is provided below. After filling it in, you can print it or email it to yourself.

- Goal:(select one) I want to drink no more than drink(s) on any day and no more than drink(s) per week OR I want to stop drinking.

- Timing: I will start on this date:

- Reasons: My most important reasons to make these changes are:

- Strategies: I will use these strategies:

- People: The people who can help me are (names and how they can help):

- Signs of success: I will know my plan is working if:

- Possible roadblocks: Some things that might interfere—and how I’ll handle them:

Reminder strategies

Change can be hard, so it helps to have concrete reminders of why and how you’ve decided to do it. Some standard options include carrying a change plan in your wallet or posting sticky notes at home. Also consider these high-tech ideas:

- Fill out a change plan, email it to your personal (non-work) account, store it in a private online folder, and review it weekly.

- Store your goals, reasons, or strategies in your mobile phone as short text messages or notepad entries that you can retrieve when an urge hits.

- Set up automated mobile phone or email calendar alerts that deliver reminders when you choose, such as a few hours before you usually go out. (Email providers such as Gmail and Yahoo mail have online calendars with alert options.)

- Create passwords that are motivating phrases in code, which you’ll reinforce each time you log in, such as 1Day@aTime, 1stThings1st!, or 0Pain=0Gain.

Social support to stop drinking

One potential challenge when people stop drinking is rebuilding a life without alcohol. It may be important to:

- Educate family and friends.

- Develop new interests and social groups.

- Find rewarding ways to spend your time that don’t involve alcohol.

- Ask for help from others.

When asking for support from friends or significant others, be specific. This could include:

- Not offering you alcohol

- Not using alcohol around you

- Giving words of support and withholding criticism

- Not asking you to take on new demands right now

- Going to a group like Alcoholics Anonymous 48

Consider joining Alcoholics Anonymous or another mutual support group (see links below). Recovering people who attend support groups regularly do better than those who do not. Groups can vary widely, so shop around for one that’s comfortable. You’ll get more out of it if you become actively involved by having a sponsor and reaching out to other members for assistance.

- Alcoholics Anonymous (https://www.aa.org)

- Moderation Management (https://moderation.org)

- Secular Organizations for Sobriety (https://www.sossobriety.org)

- SMART Recovery (https://www.smartrecovery.org)

- Women for Sobriety (https://womenforsobriety.org)

- Al-Anon Family Groups (https://al-anon.org)

- Adult Children of Alcoholics (https://adultchildren.org)

- National Council on Alcoholism and Drug Dependence (https://recovered.org)

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (https://www.niaaa.nih.gov)

- National Organization on Fetal Alcohol Syndrome (https://fasdunited.org)

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (https://findtreatment.gov)

Alcoholics anonymous

Alcoholics Anonymous or AA is a fellowship of people who come together to solve their drinking problem 49. Alcoholics Anonymous is FREE and its membership is open to anyone who wants to do something about their drinking problem. It’s FREE to attend AA meetings. There are no age or education requirements to participate. A.A.’s primary purpose is to help alcoholics to achieve sobriety. A.A. does not promise to solve your life’s problems, but AA can show you how to live without drinking “one day at a time.” You stay away from that “first drink.” If there is no first one, there cannot be a tenth one. And when you get rid of alcohol, you’ll find that your life will became much more manageable. To find Alcoholics Anonymous meetings near you please go here: https://www.aa.org/find-aa

Bill W. and Dr. Bob S. (both gentlemen were alcoholics) founded Alcoholics Anonymous in 1935 at Akron, Ohio. They wrote the book Twelve Steps and Twelve Traditions to share their 18 years of collective experience within the Fellowship on how A.A. members recover, and how the society functions. A.A.’s 12 Traditions apply to the life of the Fellowship itself. They outline the means by which A.A. maintains its unity and relates itself to the world about it, the way it lives and grows. The basic principles of A.A., as they are known today, were borrowed mainly from the fields of religion and medicine, though some ideas upon which success finally depended were the result of noting the behavior and needs of the Fellowship itself.

Patients do not need a strong religious background to be successful in AA; they only need the belief in a power higher than themselves. Patients who have tried AA may have had a bad past experience. Patients should try at least 5-10 different meetings before giving up on the AA approach because each meeting is different. For example, women often do better at meetings for women only because the issues for female patients with alcoholism are different from the issues for male patients with alcoholism. A meeting in the suburbs might not be appropriate for someone from the inner city and vice versa. No randomized trials of AA have been performed, but a US Veterans Administration study suggested that patients who attended meetings did much better than those who refused to go.

AA meetings near me

To find Alcoholics Anonymous meetings near you please click here: https://www.aa.org/find-aa

12 steps of AA

A.A.’s 12 Steps are a group of principles, spiritual in their nature, which, if practiced as a way of life, can expel the obsession to drink and enable the sufferer to become happily and usefully whole. The 12 Steps Alcoholics Anonymous can be found in the book Alcoholics Anonymous 50. The AA 12-step approach involves psychosocial techniques used in changing behavior (eg, rewards, social support networks, role models). Each new person is assigned an AA sponsor (a person recovering from alcoholism who supervises and supports the recovery of the new member). The sponsor should be older and should be of the same sex as the patient (opposite sex if the patient is homosexual).

- We admitted we were powerless over alcohol—that our lives had become unmanageable. (https://www.aa.org/sites/default/files/2022-01/en_step1.pdf)

- Came to believe that a Power greater than ourselves could restore us to sanity. (https://www.aa.org/sites/default/files/2022-01/en_step2.pdf)

- Made a decision to turn our will and our lives over to the care of God as we understood Him. (https://www.aa.org/sites/default/files/2022-01/en_step3.pdf)

- Made a searching and fearless moral inventory of ourselves. (https://www.aa.org/sites/default/files/2022-01/en_step4.pdf)

- Admitted to God, to ourselves, and to another human being the exact nature of our wrongs. (https://www.aa.org/sites/default/files/2022-01/en_step5.pdf)

- Were entirely ready to have God remove all these defects of character. (https://www.aa.org/sites/default/files/2022-01/en_step6.pdf)

- Humbly asked Him to remove our shortcomings. (https://www.aa.org/sites/default/files/2022-01/en_step7.pdf)

- Made a list of all persons we had harmed, and became willing to make amends to them all. (https://www.aa.org/sites/default/files/2022-01/en_step8.pdf)

- Made direct amends to such people wherever possible, except when to do so would injure them or others. (https://www.aa.org/sites/default/files/2022-01/en_step9.pdf)

- Continued to take personal inventory and when we were wrong promptly admitted it. (https://www.aa.org/sites/default/files/2022-01/en_step10_0.pdf)

- Sought through prayer and meditation to improve our conscious contact with God as we understood Him, praying only for knowledge of His will for us and the power to carry that out. (https://www.aa.org/sites/default/files/2022-01/en_step11.pdf)

- Having had a spiritual awakening as the result of these steps, we tried to carry this message to alcoholics, and to practice these principles in all our affairs. (https://www.aa.org/sites/default/files/2022-01/en_step12.pdf)

What cause alcohol use disorder?

The cause of alcohol use disorder is not well understood; however, several factors are thought to contribute to its development. These include the home environment, peer interactions, genetic factors, level of cognitive functioning, and certain existing personality disorders 51.Personality disorders associated with the development of an alcohol use disorder include disinhibition and impulsivity-type disorders, as well as depressive and socialization-related disorders 52.

Almost half of the people with any substance abuse problem, including alcohol use disorder, also had a co-existing mental illness 53, 54. Overall, alcohol use disorder tends to be more common in individuals with less education and low income.

Multiple theories have been suggested as to why some people develop alcohol use disorders. Some of the more evidence-supported theories include positive-effect regulation, negative-effect regulation, pharmacological vulnerability, and deviance proneness. Positive-effect regulation results in drinking for positive rewards (such as feelings of euphoria). Negative-effect regulation is seen when one drinks to cope with feelings of a negative nature, such as depression, anxiety, or feelings of worthlessness. Pharmacological vulnerability makes a note of an individual’s varied response to both acute and chronic effects of alcohol intake and the individual differences in the body’s ability to metabolize the alcohol. Deviance proneness speaks more to an individual’s tendency towards deviant behavior established during childhood, often due to a deficiency in socialization at an early age.

Some of the genes suspected in alcohol use disorder include GABRG2 and GABRA2, COMT Val 158Met, DRD2 Taq1A, and KIAA0040.

Risk factors for alcoholism

There is no single factor that accounts for the variation in individual risk of developing alcohol-use disorders. Alcohol use may begin in the teens, but alcohol use disorder occurs more frequently in the 20s and 30s, though it can start at any age. The evidence suggests that harmful alcohol use and alcohol dependence have a wide range of causal factors

- Family history of alcohol abuse. The risk of alcohol use disorder is higher for people who have a parent or other close relative who has problems with alcohol. This may be influenced by genetic factors.

- offspring of parents with alcohol dependence are four times more likely to develop alcohol dependence

- genetic studies (particularly those in twins) has clearly demonstrated a genetic component to the risk of alcohol dependence

- a meta-analysis of 9,897 twin pairs from Australian and US studies found the heritability of alcohol dependence to be in excess of 50%

- Psychological factors

- psychiatric comorbidity particularly depression, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder (BPD), anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), psychosis and drug misuse. It’s common for people with a mental health disorder such as anxiety, depression, schizophrenia or bipolar disorder to have problems with alcohol or other substances.

- Stress, adverse life events and abuse

- Sex: men are twice as likely to be problem drinkers

- Occupation:

- publicans and brewers have an increased access to drink and are at a higher risk

- heavy drinking is seen as the norm in some jobs e.g. sailors

- Homelessness:

- a third of homeless people have a drink problem

- Steady drinking over time. Drinking too much on a regular basis for an extended period or binge drinking on a regular basis can lead to alcohol-related problems or alcohol use disorder.

- Started drinking at an early age. People who begin drinking — especially binge drinking — at an early age are at a higher risk of alcohol use disorder.

- History of trauma. People with a history of emotional or other trauma are at increased risk of alcohol use disorder.

- Having bariatric surgery (weight-loss surgery — involves making changes to your digestive system to help you lose weight). Some research studies indicate that having bariatric surgery may increase the risk of developing alcohol use disorder or of relapsing after recovering from alcohol use disorder.

- Social and cultural factors. Having friends or a close partner who drinks regularly could increase your risk of alcohol use disorder. The glamorous way that drinking is sometimes portrayed in the media also may send the message that it’s OK to drink too much. For young people, the influence of parents, peers and other role models can impact risk.

Alcohol addiction prevention

Early intervention can prevent alcohol-related problems in teens. If you have a teenager, be alert to signs and symptoms that may indicate a problem with alcohol:

- Loss of interest in activities and hobbies and in personal appearance

- Red eyes, slurred speech, problems with coordination and memory lapses

- Difficulties or changes in relationships with friends, such as joining a new crowd

- Declining grades and problems in school

- Frequent mood changes and defensive behavior

You can help prevent teenage alcohol use:

- Set a good example with your own alcohol use.

- Talk openly with your child, spend quality time together and become actively involved in your child’s life.

- Let your child know what behavior you expect — and what the consequences will be if he or she doesn’t follow the rules.

Alcoholism signs and symptoms

A few mild symptoms — which you might not see as trouble signs — can signal the start of a drinking problem. It helps to know the signs so you can make a change early. If heavy drinking continues, then over time, the number and severity of symptoms can grow and add up to “alcohol use disorder.” Doctors diagnose alcohol use disorder when a patient’s drinking causes distress or harm. See if you recognize any of these symptoms in yourself. And don’t worry — even if you have symptoms, you can take steps to reduce your risks.

Alcohol use disorder can be mild, moderate or severe, based on the number of symptoms you experience.

Alcohol use disorder signs and symptoms may include:

- Being unable to limit the amount of alcohol you drink

- Wanting to cut down on how much you drink or making unsuccessful attempts to do so

- Spending a lot of time drinking, getting alcohol or recovering from alcohol use

- Feeling a strong craving or urge to drink alcohol

- Failing to fulfill major obligations at work, school or home due to repeated alcohol use

- Continuing to drink alcohol even though you know it’s causing physical, social or interpersonal problems

- Giving up or reducing social and work activities and hobbies

- Using alcohol in situations where it’s not safe, such as when driving or swimming

- Developing a tolerance to alcohol so you need more to feel its effect or you have a reduced effect from the same amount

- Experiencing withdrawal symptoms — such as nausea, sweating and shaking — when you don’t drink, or drinking to avoid these symptoms

Alcohol use disorder can include periods of alcohol intoxication and symptoms of withdrawal.

- Alcohol intoxication results as the amount of alcohol in your bloodstream increases. The higher the blood alcohol concentration is, the more impaired you become. Alcohol intoxication causes behavior problems and mental changes. These may include inappropriate behavior, unstable moods, impaired judgment, slurred speech, impaired attention or memory, and poor coordination. You can also have periods called “blackouts,” where you don’t remember events. Very high blood alcohol levels can lead to coma or even death.

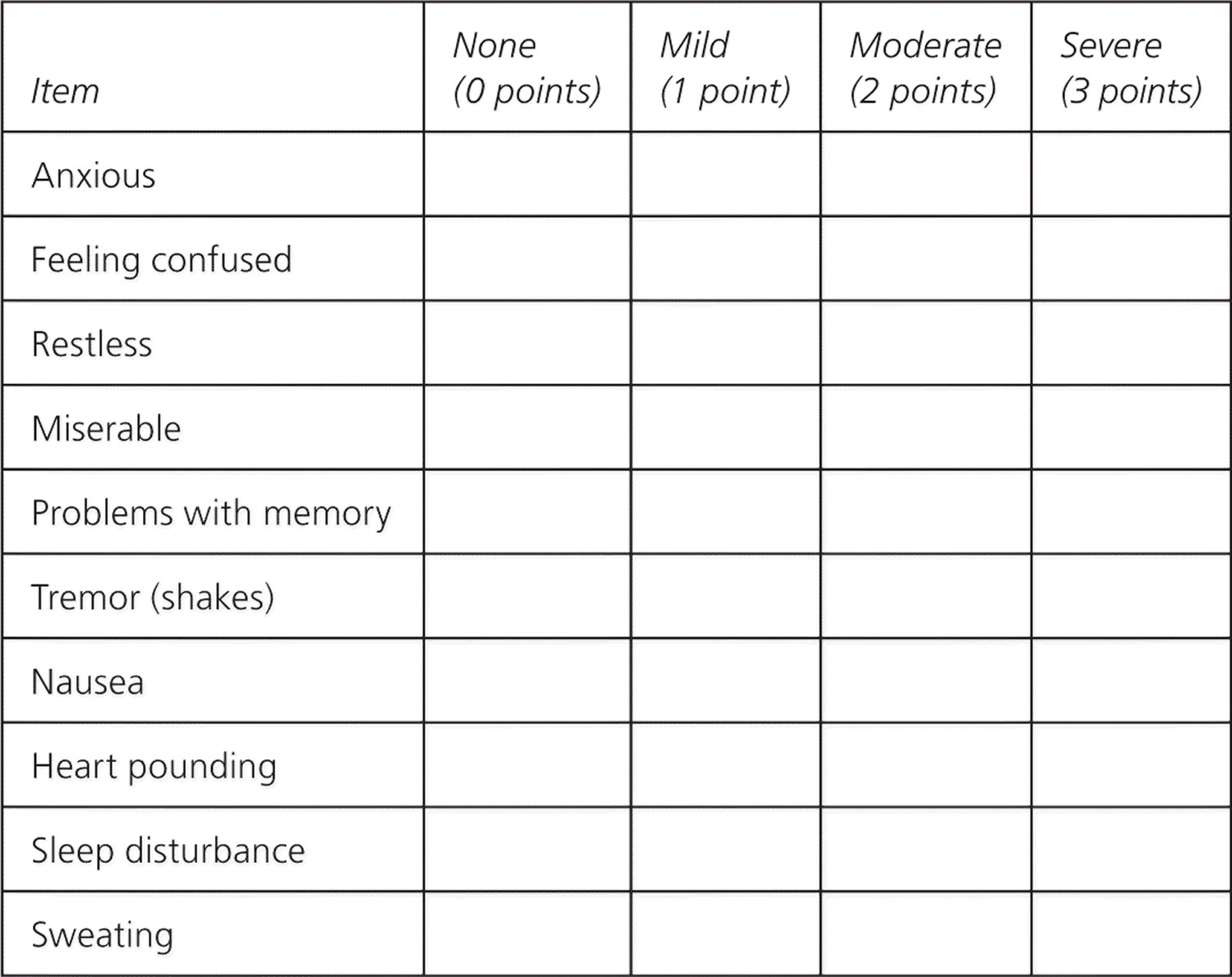

- Alcohol withdrawal can occur when alcohol use has been heavy and prolonged and is then stopped or greatly reduced. It can occur within several hours to four or five days later. Signs and symptoms include sweating, rapid heartbeat, hand tremors, problems sleeping, nausea and vomiting, hallucinations, restlessness and agitation, anxiety, and occasionally seizures. Symptoms can be severe enough to impair your ability to function at work or in social situations.

The more symptoms you have, the more serious the problem is. If you think you might have an alcohol use disorder, see your health care provider for an evaluation. Your provider can help make a treatment plan, prescribe medicines, and if needed, give you treatment referrals.

People with alcohol use disorder may also report frequent falls, blackout spells, unsteadiness, or visual disturbances 51. They may report seizures if they went a few days without drinking, or tremors, confusion, emotional disturbances, and frequent job changes. They may also report social issues, such as job termination, separation/divorce, estrangement from family, or loss of home. They may also report sleep disturbances.

People with alcohol use disorder may have hypertension (high blood pressure) or insomnia (trouble falling and staying asleep) initially. In later stages, the patient may complain of nausea or vomiting, hematemesis (vomiting blood), bloated abdomen, epigastric pain, weight loss, jaundice, or other symptoms or signs suggestive of liver dysfunction. They may be asymptomatic early on.

People with alcohol use disorder may exhibit signs of cerebellar dysfunction, such as ataxia (impaired balance or coordination) or difficulty with fine motor skills, on exam. They may exhibit slurred speech, tachycardia (fast heart rate), memory impairment, nystagmus (involuntary eye movement which may cause the eye to rapidly move from side to side, up and down or in a circle), disinhibited behavior, or hypotension (low blood pressure). People with alcohol use disorder may present with tremors, confusion/mental status changes, asterixis, reddsih palms, jaundice, ascites, or other signs of advanced liver disease. There may also be spider angiomata, hepatomegaly/splenomegaly (early; liver becomes cirrhotic and shrunken in advanced disease). They may develop bleeding disorders, anemia, gastritis/ulcers, or pancreatitis as complications of alcohol use. Labs will reveal anemia, thrombocytopenia, coagulopathy, hyponatremia, hyperammonemia, elevated ammonia levels, or decreased B12/folate levels as the advanced liver disease develops.

Alcohol abuse complications

Alcohol depresses your central nervous system. In some people, the initial reaction may be stimulation. But as you continue to drink, you become sedated.

Too much alcohol affects your speech, muscle coordination and vital centers of your brain. A heavy drinking binge may even cause a life-threatening coma or death. This is of particular concern when you’re taking certain medications that also depress the brain’s function.

Alcohol abuse impacting on your safety

Excessive drinking can reduce your judgment skills and lower inhibitions, leading to poor choices and dangerous situations or behaviors, including:

- Motor vehicle accidents and other types of accidental injury, such as drowning

- Relationship problems

- Poor performance at work or school

- Increased likelihood of committing violent crimes or being the victim of a crime

- Legal problems or problems with employment or finances

- Problems with other substance use

- Engaging in risky, unprotected sex, or experiencing sexual abuse or date rape

- Increased risk of attempted or completed suicide

Alcohol abuse impacting on your health

Drinking too much alcohol on a single occasion or over time can cause health problems, including:

- Liver disease. Heavy drinking can cause increased fat in the liver (hepatic steatosis), inflammation of the liver (alcoholic hepatitis), and over time, irreversible destruction and scarring of liver tissue (cirrhosis).

- Digestive problems. Heavy drinking can result in inflammation of the stomach lining (gastritis), as well as stomach and esophageal ulcers. It can also interfere with absorption of B vitamins and other nutrients. Heavy drinking can damage your pancreas or lead to inflammation of the pancreas (pancreatitis).

- Heart problems. Excessive drinking can lead to high blood pressure and increases your risk of an enlarged heart, heart failure or stroke. Even a single binge can cause a serious heart arrhythmia called atrial fibrillation.

- Diabetes complications. Alcohol interferes with the release of glucose from your liver and can increase the risk of low blood sugar (hypoglycemia). This is dangerous if you have diabetes and are already taking insulin to lower your blood sugar level.

- Sexual function and menstruation issues. Excessive drinking can cause erectile dysfunction in men. In women, it can interrupt menstruation.

- Eye problems. Over time, heavy drinking can cause involuntary rapid eye movement (nystagmus) as well as weakness and paralysis of your eye muscles due to a deficiency of vitamin B-1 (thiamin). A thiamin deficiency can also be associated with other brain changes, such as irreversible dementia, if not promptly treated.

- Birth defects. Alcohol use during pregnancy may cause miscarriage. It may also cause fetal alcohol syndrome, resulting in giving birth to a child who has physical and developmental problems that last a lifetime.

- Bone damage. Alcohol may interfere with the production of new bone. This bone loss can lead to thinning bones (osteoporosis) and an increased risk of fractures. Alcohol can also damage bone marrow, which makes blood cells. This can cause a low platelet count, which may result in bruising and bleeding.

- Neurological complications. Excessive drinking can affect your nervous system, causing numbness and pain in your hands and feet, disordered thinking, dementia, and short-term memory loss.

- Wernicke encephalopathy: Wernicke’s encephalopathy is caused by acute thiamine (Vitamin B1) deficiency. Wernicke encephalopathy causes brain damage in the lower parts of the brain called the thalamus and hypothalamus. Symptoms of Wernicke encephalopathy include:

- Confusion and loss of mental activity that can progress to coma and death

- Loss of muscle coordination (ataxia) that can cause leg tremor

- Vision changes such as abnormal eye movements (back and forth movements called nystagmus), double vision, eyelid drooping

- Alcohol withdrawal

- Vitamin B1 (Thiamine) is usually given by injection into a vein or a muscle as soon as possible. This may improve symptoms of:

- Confusion or delirium

- Difficulties with vision and eye movement

- Lack of muscle coordination

- Korsakoff syndrome or Korsakoff psychosis, tends to develop as Wernicke encephalopathy symptoms go away. Korsakoff psychosis results from permanent damage to areas of the brain involved with memory (anterograde and retrograde amnesia), often with confabulation (making up stories) and preceded by Wernicke encephalopathy. Symptoms of Korsakoff syndrome include:

- Inability to form new memories

- Loss of memory, can be severe

- Making up stories (confabulation)

- Seeing or hearing things that are not really there (hallucinations)

- Vitamin B1 (Thiamine) often does not improve loss of memory and intellect that occur with Korsakoff syndrome. Stopping alcohol use can prevent more loss of brain function and damage to nerves.

- Wernicke encephalopathy: Wernicke’s encephalopathy is caused by acute thiamine (Vitamin B1) deficiency. Wernicke encephalopathy causes brain damage in the lower parts of the brain called the thalamus and hypothalamus. Symptoms of Wernicke encephalopathy include:

- Weakened immune system. Excessive alcohol use can make it harder for your body to resist disease, increasing your risk of various illnesses, especially pneumonia.

- Increased risk of cancer. Long-term, excessive alcohol use has been linked to a higher risk of many cancers, including mouth, throat, liver, esophagus, colon and breast cancers. Even moderate drinking can increase the risk of breast cancer.

- Medication and alcohol interactions. Some medications interact with alcohol, increasing its toxic effects. Drinking while taking these medications can either increase or decrease their effectiveness, or make them dangerous.

Alcoholism diagnosis

You’re likely to start by seeing your doctor. If your doctor suspects you have a problem with alcohol, he or she may refer you to a mental health professional.

To assess your problem with alcohol, your doctor will likely:

- Ask you several questions related to your drinking habits. The doctor may ask for permission to speak with family members or friends. However, confidentiality laws prevent your doctor from giving out any information about you without your consent.

- Perform a physical exam. Your doctor may do a physical exam and ask questions about your health. There are many physical signs that indicate complications of alcohol use.

- Lab tests and imaging tests. While there are no specific tests to diagnose alcohol use disorder, certain patterns of lab test abnormalities may strongly suggest it. And you may need tests to identify health problems that may be linked to your alcohol use. Damage to your organs may be seen on tests.

- Complete a psychological evaluation. This evaluation includes questions about your symptoms, thoughts, feelings and behavior patterns. You may be asked to complete a questionnaire to help answer these questions.

- Use the DSM-5 criteria. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), published by the American Psychiatric Association, is often used by mental health professionals to diagnose mental health conditions.

DSM-5 alcohol use disorder

DSM-5 Criteria for the Diagnosis of Alcohol Use Disorder 55:

- Criterion A. A problematic pattern of alcohol use leading to clinically significant impairment or distress, as manifested by at least two of the following, occurring within a 12-month period:

- Alcohol is often taken in larger amounts or over a longer period than was intended.

- There is a persistent desire or unsuccessful efforts to cut down or control alcohol use.

- A great deal of time is spent in activities necessary to obtain alcohol, use alcohol, or recover from its effects.

- Craving, or a strong desire or urge to use alcohol.

- Recurrent alcohol use resulting in a failure to fulfill major role obligations at work, school, or home.

- Continued alcohol use despite having persistent or recurrent social or interpersonal problems caused or exacerbated by the effects of alcohol.

- Important social, occupational, or recreational activities are given up or reduced because of alcohol use.

- Recurrent alcohol use in situations in which it is physically hazardous.

- Alcohol use is continued despite knowledge of having a persistent or recurrent physical or psychological problem that is likely to have been caused or exacerbated by alcohol.

- Tolerance, as defined by either of the following:

- a. A need for markedly increased amounts of alcohol to achieve intoxication or desired effect.

- b. A markedly diminished effect with continued use of the same amount of alcohol.

- Withdrawal, as manifested by either of the following:

- a. The characteristic withdrawal syndrome for alcohol.

- b. Alcohol (or a closely related substance, such as a benzodiazepine) is taken to relieve or avoid withdrawal symptoms.

Specify if:

- In early remission: After full criteria for alcohol use disorder were previously met, none of the criteria for alcohol use disorder have been met for at least 3 months but for less than 12 months (with the exception that Criterion A4, “Craving, or a strong desire or urge to use alcohol,” may be met).

- In sustained remission: After full criteria for alcohol use disorder were previously met, none of the criteria for alcohol use disorder have been met at any time during a period of 12 months or longer (with the exception that Criterion A4, “Craving, or a strong desire or urge to use alcohol,” may be met).

Specify if:

- In a controlled environment: This additional specifier is used if the individual is in an environment where access to alcohol is restricted.

Alcohol use disorder is defined by a cluster of behavioral and physical symptoms, which can include withdrawal, tolerance, and craving. Alcohol withdrawal is characterized by withdrawal symptoms that develop approximately 4-12 hours after the reduction of intake following prolonged, heavy alcohol ingestion. Because withdrawal from alcohol can be unpleasant and intense, individuals may continue to consume alcohol despite adverse consequences, often to avoid or to relieve withdrawal symptoms. Some withdrawal symptoms (e.g., sleep problems) can persist at lower intensities for months and can contribute to relapse. Once a pattern of repetitive and intense use develops, individuals with alcohol use disorder may devote substantial periods of time to obtaining and consuming alcoholic beverages.

Craving for alcohol is indicated by a strong desire to drink that makes it difficult to think of anything else and that often results in the onset of drinking. School and job performance may also suffer either from the aftereffects of drinking or from actual intoxication at school or on the job; child care or household responsibilities may be neglected; and alcohol-related absences may occur from school or work. The individual may use alcohol in physically hazardous circumstances (e.g., driving an automobile, swimming, operating machinery while intoxicated). Finally, individuals with an alcohol use disorder may continue to consume alcohol despite the knowledge that continued consumption poses significant physical (e.g., blackouts, liver disease), psychological (e.g., depression), social, or interpersonal problems (e.g., violent arguments with spouse while intoxicated, child abuse).

Laboratory studies

Currently, there are no biomarkers that can directly identify alcoholism 56. Alcohol biomarkers are physiological indicators of alcohol exposure or ingestion and may reflect the presence of an alcohol use disorder. These biomarkers are not meant to be a substitute for a comprehensive history and physical examination by an appropriate health professional. Instead, alcohol biomarkers should be a complement to self-reported measures of drinking. Alcohol biomarkers are generally divided into indirect and direct biomarkers 57.

Indirect alcohol biomarkers suggest heavy alcohol use by detecting the toxic effects that alcohol may have had on organ systems or body chemistry 57. Indirect alcohol biomarkers, which suggest heavy alcohol use by detecting the toxic effects of alcohol, include aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), gamma glutamyltransferase (GGT), mean corpuscular volume (MCV), and carbohydrate-deficient transferrin (CDT).

Gamma glutamyltransferase (GGT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and mean corpuscular volume (MCV) are the most frequently used indirect biomarkers 58. As a screen for alcohol dependence, the sensitivity/specificity of carbohydrate-deficient transferrin (CDT) is generally higher than AST, ALT, GGT, or MCV 59, 60. Carbohydrate-deficient transferrin (CDT) is less sensitive/specific in women than men 61.

Carbohydrate-deficient transferrin (CDT) is a collection of various isoforms of the iron transport protein transferrin 58. Alcohol consumption above 50-80 g/d for 2-3 weeks appears to increase serum concentrations of CDT 60. CDT tends to distinguish chronic heavy drinkers from light social drinkers 58. A number of different ways are available to measure CDT; some may be better than others, depending on factors such as the type of alcohol consumption and gender 62.

The combination of gamma glutamyltransferase (GGT) and CDT compared with gamma glutamyltransferase (GGT) or CDT alone shows a higher diagnostic sensitivity, a higher diagnostic specificity, and a stronger correlation with the actual amounts of alcohol consumption 59, 60. Combination GGT/CDT values appear to increase after the daily alcohol consumption exceeds a threshold of 40 g 59. This approach is cost-effective, easy to manage in hospital laboratories, and should be suitable for routine clinical care 59.

Other indirect alcohol biomarkers of emerging interest include total serum sialic acid (TSA), 5-hydroxytryptophol (5-HTOL), N-acetyl-beta-hexosaminidase (Beta-Hex), plasma sialic acid index of apolipoprotein J (SIJ), and salsolinol 63.

Direct alcohol biomarkers are analytes of alcohol metabolism 57.

Direct alcohol biomarkers include alcohol itself and ethyl glucuronide (EtG) 57.

A blood alcohol level might be helpful in the office if the patient appears intoxicated but is denying alcohol abuse. Blood alcohol levels that indicate alcoholism with a high degree of reliability are as follows:

- A blood alcohol level in excess of 300 mg/dL in a patient who appears intoxicated but denies alcohol abuse

- A blood alcohol level of greater than 150 mg/dL without gross evidence of intoxication

- A blood alcohol level of greater than 100 mg/dL upon routine examination indicates alcoholism with a high degree of reliability

The short half-life of alcohol limits its use widely as a biomarker 59. As the blood alcohol level detects alcohol intake in the previous few hours, it is not necessarily a good indicator of chronic excessive drinking 58.

Ethyl glucuronide (EtG) is a minor, nonoxidative, water-soluble, stable, and direct metabolite of alcohol that is formed by the conjugation of ethanol with activated glucoronic acid 59. Shortly after alcohol intake, even in small amounts, EtG becomes positive 59. After complete cessation of alcohol intake, EtG can be detected in urine for up to 5 days after heavy binge drinking 59, making EtG an important biomarker of recent alcohol consumption 58. A 2006 report by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration states that the use of EtG should be considered as a potential valuable clinical tool, but the use of EtG in forensic settings is premature.

Features of EtG are as follows:

- Becomes positive shortly after intake of alcohol, even in small amounts

- After complete cessation of alcohol intake, EtG can be detected in urine for up to 5 days after heavy binge drinking

Other direct alcohol biomarkers of emerging interest include acetaldehyde, fatty acid ethyl esters (FAEE), Ethyl Sulfate (EtS), and Phosphatidylethanol (PEth) 63.

Alcoholism treatment

Most people with an alcohol use disorder can benefit from some form of treatment. Medical treatments include medicines and behavioral therapies. For many people, using both types gives them the best results. People who are getting treatment for alcohol use disorder may also find it helpful to go to a support group such as Alcoholics Anonymous (AA). If you have an alcohol use disorder and a mental illness, it is important to get treatment for both.

Treatment for alcohol use disorder may include: