Alvarado score

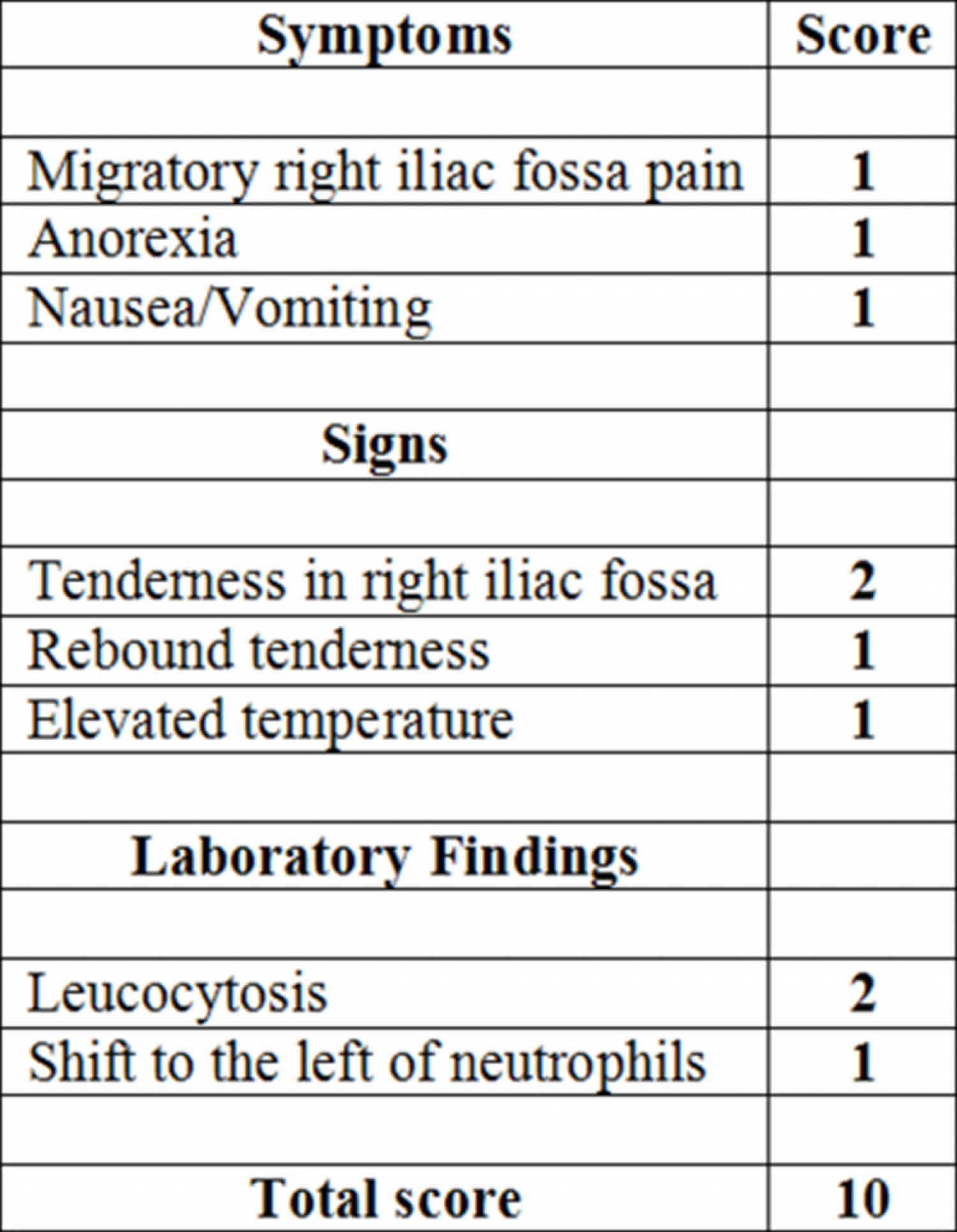

Alvarado score is the most widely used clinical prediction tool to facilitate decision-making in patients with acute appendicitis 1. The Alvarado score is the most widely used clinical prediction rule for acute appendicitis and sums up 3 symptoms and 3 signs as well as the results of standard blood tests to give an overall score out of 10 (Table 1) 2. The two most important factors, tenderness in the right lower quadrant and leukocytosis, are assigned 2 points, and the six other factors are assigned 1 point each, for a possible total score of 10 points. On the basis of the Alvarado score, 3 groups of patients are identified 2. A score of 5 or 6 is compatible with the diagnosis of acute appendicitis. A score of 7 or 8 indicates a probable appendicitis, and a score of 9 or 10 indicates a very probable acute appendicitis. Patients with a Alvarado score of 1–4 can be discharged home, those with a Alvarado score 5–6 should be admitted and those with a Alvarado score of 7–10 should be considered candidates for surgery.

A popular mnemonic used to remember the Alvarado score factors is MANTRELS – Migration to the right iliac fossa, Anorexia, Nausea/Vomiting, Tenderness in the right iliac fossa, Rebound pain, Elevated temperature (fever), Leukocytosis, and Shift of leukocytes to the left (factors listed in the same order as presented above). Due to the popularity of this mnemonic, the Alvarado score is sometimes referred to as the MANTRELS score.

A useful mnemonic to remember the modified Alvarado score is: MAFLTRN – My Appendix Feels Likely To Rupture Now (2 points for Anorexia and Tenderness in the right iliac fossa, one for all the others).

The Alvarado score has a very low sensitivity and a low specificity, especially in women who can have gynecological diseases mimicking appendicitis. The score has been modified to try and find adapted scores with higher clinical importance. Trials have studied the usefulness for the score in guiding the management of patients with pain in the right fossa, for example to see which patients need a CT scan and which patients need surgery.

Table 1. The Alvarado score

| Feature | Score |

|---|---|

| Migration of abdominal pain that migrates to the right lower quadrant | 1 |

| Anorexia and/or ketones in the urine | 1 |

| Nausea and/or vomiting | 1 |

| Right lower quadrant tenderness | 2 |

| Rebound pain | 1 |

| Elevated temperature > 37.5° C (99.5 °F) by oral measurement | 1 |

| Leucocytosis (>10,000 white blood cells per microliter) | 2 |

| Left shift of white cell count with >75% neutrophils | 1 |

| Total | 10 |

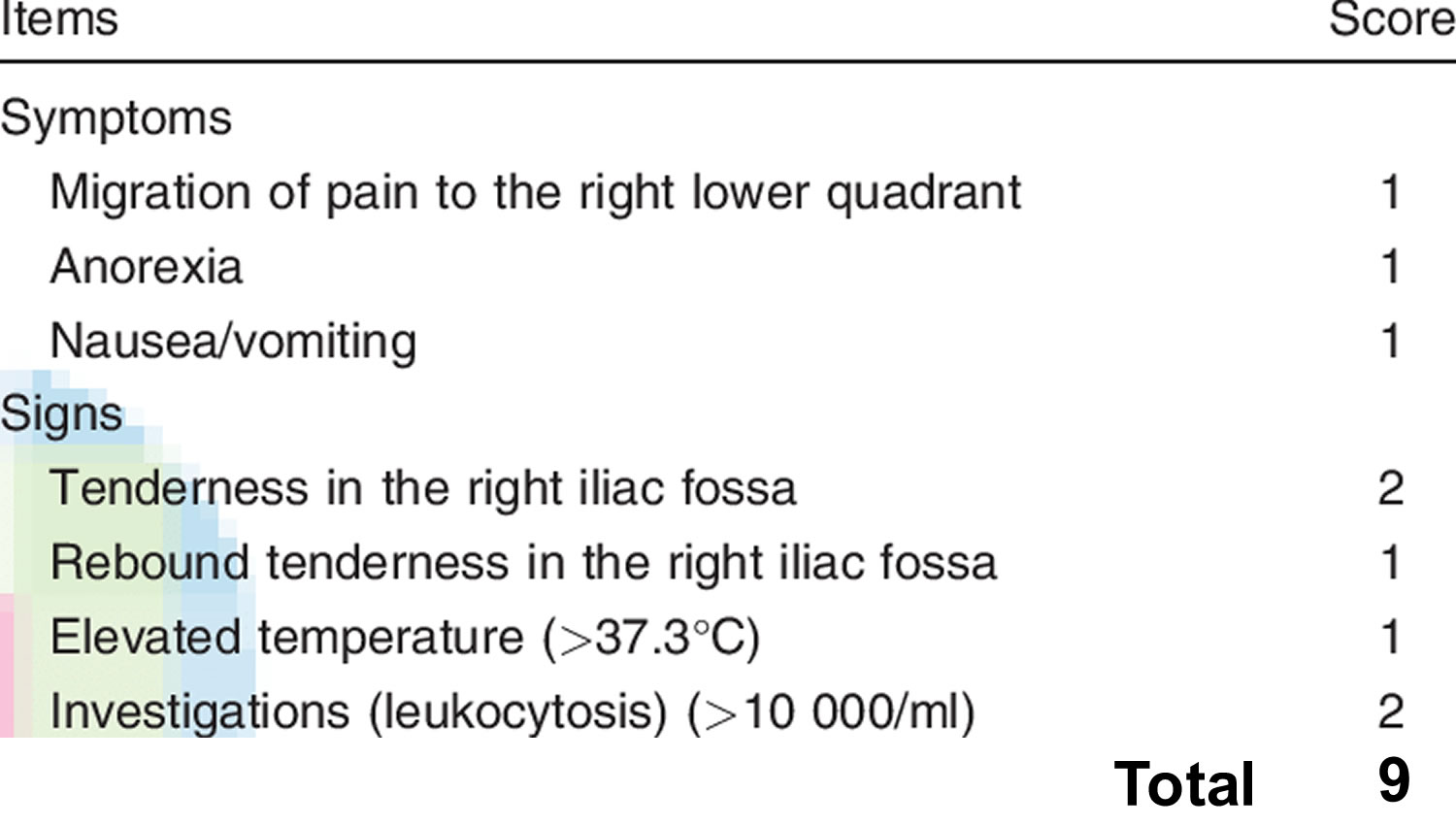

Table 2. Modified Alvarado score

Footnote: The modified Alvarado score has been widely accepted after it was successfully tested in different studies 3.

Footnote: The modified Alvarado score has been widely accepted after it was successfully tested in different studies 3.

Alvarado score interpretation

A recent review of the published data on the Alvarado score reported that it is most useful in predicting the absence of appendicitis, and an Alvarado score below 5 has a sensitivity of 94%–99% for appendicitis not being present 4. The authors concluded that a score of 5 or less rules out appendicitis 4. When it comes to positively establishing the presence of acute appendicitis, the Alvarado score is less reliable; the same review stated that “the pooled diagnostic accuracy in terms of ‘ruling in’ appendicitis at a cut-point of 7 points is not sufficiently specific in any patient group to proceed directly to surgery” 4. The Alvarado score is well calibrated in men, but tends to overpredict the presence of acute appendicitis in women 4. In children, the score has also been shown to be inaccurate 5.

Appendicitis

Appendicitis is defined as an inflammation of the inner lining of the vermiform appendix, a finger-shaped pouch that projects from your colon on the lower right side of your abdomen. Appendicitis causes pain in your lower right abdomen. However, in most people, pain begins around the navel and then moves. As inflammation worsens, appendicitis pain typically increases and eventually becomes severe. Although anyone can develop appendicitis, most often it occurs in people between the ages of 10 and 30. Standard treatment is surgical removal of the appendix.

Despite diagnostic and therapeutic advancement in medicine, appendicitis remains a clinical emergency and is one of the more common causes of acute abdominal pain.

Appendicitis causes

A blockage in the lining of the appendix that results in infection is the likely cause of appendicitis. The bacteria multiply rapidly, causing the appendix to become inflamed, swollen and filled with pus. If not treated promptly, the appendix can rupture.

The most common causes of obstruction of the appendiceal lumen include lymphoid hyperplasia secondary to inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) or infections (more common during childhood and in young adults), fecal stasis and fecaliths (more common in elderly patients), parasites (especially in Eastern countries), or, more rarely, foreign bodies and neoplasms.

Fecaliths form when calcium salts and fecal debris become layered around a nidus of inspissated fecal material located within the appendix. Lymphoid hyperplasia is associated with various inflammatory and infectious disorders including Crohn disease, gastroenteritis, amebiasis, respiratory infections, measles, and mononucleosis.

Obstruction of the appendiceal lumen has less commonly been associated with bacteria (Yersinia species, adenovirus, cytomegalovirus, actinomycosis, Mycobacteria species, Histoplasma species), parasites (eg, Schistosomes species, pinworms, Strongyloides stercoralis), foreign material (eg, shotgun pellet, intrauterine device, tongue stud, activated charcoal), tuberculosis, and tumors.

Appendicitis signs and symptoms

The clinical presentation of appendicitis is notoriously inconsistent. The classic history of anorexia and periumbilical pain followed by nausea, right lower quadrant pain, and vomiting occurs in only 50% of cases. The site of your pain may vary, depending on your age and the position of your appendix. When you’re pregnant, the pain may seem to come from your upper abdomen because your appendix is higher during pregnancy.

Features of appendicitis include the following 6:

- Abdominal pain: Most common symptom

- Nausea: 61-92% of patients

- Anorexia: 74-78% of patients

- Vomiting: Nearly always follows the onset of pain; vomiting that precedes pain suggests intestinal obstruction

- Diarrhea or constipation: As many as 18% of patients

Features of the abdominal pain are as follows:

- Typically begins as periumbilical or epigastric pain, then migrates to the right lower quadrant 7

- Patients usually lie down, flex their hips, and draw their knees up to reduce movements and to avoid worsening their pain

- The duration of symptoms is less than 48 hours in approximately 80% of adults but tends to be longer in elderly persons and in those with perforation.

Physical examination findings include the following:

- Rebound tenderness, pain on percussion, rigidity, and guarding: Most specific finding

- Right lower quadrant tenderness: Present in 96% of patients, but nonspecific

- Left lower quadrant tenderness: May be the major manifestation in patients with situs inversus or in patients with a lengthy appendix that extends into the left lower quadrant.

- Male infants and children occasionally present with an inflamed hemiscrotum

- In pregnant women, right lower quadrant pain and tenderness dominate in the first trimester, but in the latter half of pregnancy, right upper quadrant or right flank pain may occur

The following accessory signs may be present in a minority of patients:

- Rovsing sign (right lower quadrant pain with palpation of the left lower quadrant): Suggests peritoneal irritation

- Obturator sign (right lower quadrant pain with internal and external rotation of the flexed right hip): Suggests the inflamed appendix is located deep in the right hemipelvis

- Psoas sign (right lower quadrant pain with extension of the right hip or with flexion of the right hip against resistance): Suggests that an inflamed appendix is located along the course of the right psoas muscle

- Dunphy sign (sharp pain in the right lower quadrant elicited by a voluntary cough): Suggests localized peritonitis

- Right lower quadrant pain in response to percussion of a remote quadrant of the abdomen or to firm percussion of the patient’s heel: Suggests peritoneal inflammation

- Markle sign (pain elicited in a certain area of the abdomen when the standing patient drops from standing on toes to the heels with a jarring landing): Has a sensitivity of 74% 8

Appendicitis complications

Appendicitis can cause serious complications, such as:

- A ruptured appendix. A rupture spreads infection throughout your abdomen (peritonitis). Possibly life-threatening, this condition requires immediate surgery to remove the appendix and clean your abdominal cavity.

- A pocket of pus (abscess) that forms in the abdomen. If your appendix bursts, you may develop a pocket of infection (abscess). In most cases, a surgeon drains the abscess by placing a tube through your abdominal wall into the abscess. The tube is left in place for about two weeks, and you’re given antibiotics to clear the infection. Once the infection is clear, you’ll have surgery to remove the appendix. In some cases, the abscess is drained, and the appendix is removed immediately.

Appendicitis diagnosis

To help diagnose appendicitis, your doctor will likely take a history of your signs and symptoms and examine your abdomen.

Tests and procedures used to diagnose appendicitis include:

- Physical exam to assess your pain. Your doctor may apply gentle pressure on the painful area. When the pressure is suddenly released, appendicitis pain will often feel worse, signaling that the adjacent peritoneum is inflamed. Your doctor may also look for abdominal rigidity and a tendency for you to stiffen your abdominal muscles in response to pressure over the inflamed appendix (guarding). Your doctor may use a lubricated, gloved finger to examine your lower rectum (digital rectal exam). Women of childbearing age may be given a pelvic exam to check for possible gynecological problems that could be causing the pain.

- Blood test. This allows your doctor to check for a high white blood cell count, which may indicate an infection.

- Urine test. Your doctor may want you to have a urinalysis to make sure that a urinary tract infection or a kidney stone isn’t causing your pain.

- Imaging tests. Your doctor may also recommend an abdominal X-ray, an abdominal ultrasound, computerized tomography (CT) scan or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to help confirm appendicitis or find other causes for your pain.

Appendicitis treatment

Appendicitis treatment usually involves surgery to remove the inflamed appendix. Before surgery you may be given a dose of antibiotics to treat infection.

Surgery to remove the appendix (appendectomy)

Appendectomy can be performed as open surgery using one abdominal incision about 2 to 4 inches (5 to 10 centimeters) long (laparotomy). Or the surgery can be done through a few small abdominal incisions (laparoscopic surgery). During a laparoscopic appendectomy, the surgeon inserts special surgical tools and a video camera into your abdomen to remove your appendix.

In general, laparoscopic surgery allows you to recover faster and heal with less pain and scarring. It may be better for older adults and people with obesity.

But laparoscopic surgery isn’t appropriate for everyone. If your appendix has ruptured and infection has spread beyond the appendix or you have an abscess, you may need an open appendectomy, which allows your surgeon to clean the abdominal cavity.

Expect to spend one or two days in the hospital after your appendectomy.

Draining an abscess before appendix surgery

If your appendix has burst and an abscess has formed around it, the abscess may be drained by placing a tube through your skin into the abscess. Appendectomy can be performed several weeks later after controlling the infection.

- Kong VY, van der Linde S, Aldous C, Handley JJ, Clarke DL. The accuracy of the Alvarado score in predicting acute appendicitis in the black South African population needs to be validated. Can J Surg. 2014;57(4):E121–E125. doi:10.1503/cjs.023013 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4119125[↩]

- Alvarado A. A practical score for the early diagnosis of acute appendicitis. Ann Emerg Med. 1986;15:557–64.[↩][↩]

- Al-Hashemy AM, Seleem MI. Appraisal of the modified Alvarado Score for acute appendicits in adults. Saudi Med J 2004;25:1229-31.[↩]

- Ohle R, O’Reilly F, O’Brien KK, et al. The Alvarado score for predicting acute appendicitis: a systematic review. BMC Med. 2011;9:139.[↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Kulik DM, Uleryk EM, Maguire JL. Does this child have appendicitis? A systematic review of clinical prediction rules for children with acute abdominal pain. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013;66:95–104.[↩]

- Appendicitis. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/773895-overview[↩]

- Yeh B. Evidence-based emergency medicine/rational clinical examination abstract. Does this adult patient have appendicitis?. Ann Emerg Med. 2008 Sep. 52(3):301-3.[↩]

- Markle GB 4th. Heel-drop jarring test for appendicitis. Arch Surg. 1985 Feb. 120(2):243.[↩]