What is ameloblastoma

Ameloblastoma is a rare noncancerous (benign) locally aggressive but slow growing tumor of the jaw involving abnormal tissue growth. Ameloblastoma represents approximately 1% of oral tumors and about 9-11% of odontogenic tumors 1. The word ameloblastoma comes from the English word “amel” which means enamel and the Greek word “blastos” which means germ 2. The resulting tumors or cysts are usually not malignant (benign) but the tissue growth may be aggressive in the involved area. On occasion, tissue near the jaws, such as around the sinuses and eye sockets, may become involved as well, giving rise to facial distortion. However, this is a benign tumor so metastasis to lymph nodes, distant sites, etc., is rare and changes the staging to malignant. The thinking is that malignant ameloblastomas comprise less than 1% of all ameloblastomas 3. Malignant variations of the ameloblastoma can occur between the teenage years up to older age.

Ameloblastoma begins in the cells that form the protective enamel lining on your teeth from the residual epithelium of the tooth germ, epithelium of odontogenic cysts stratified squamous epithelium and epithelium of the enamel organ 4. Ameloblastoma arises from the mandible (frequently in the posterior region) in approximately 80% of cases, mostly in association with an unerupted tooth 5. In addition, ameloblastoma may arise from the tuberosity of maxillary sinus in approximately 20% of cases 6. In the United States, ameloblastoma accounts for 1% of all tumors/cysts of jaw, 1% of all head and neck neoplasms, and 10% of all tumors arising from mandible or maxilla 7. Ameloblastoma accounts for 9–11% of all odontogenic tumors with an incidence rate of 0.5 cases per-million 8. Ameloblastoma occurs in men more often than it occurs in women. Though it can be diagnosed at any age, ameloblastoma is most often diagnosed in adults in their 30s and 40s. Ameloblastoma can be very aggressive, growing into the jawbone and causing swelling and pain. Ameloblastoma rarely invades the orbit; if it does, it involves the orbit in the elderly with male predilection 9. Very rarely, ameloblastoma cells can spread to other areas of the body, such as the lymph nodes in the neck and the lungs. Malignancy is uncommon as are metastases, but when they occur, lungs are involved in over 80% of cases 10.

Ameloblastomas can occur over a broad age range, and most commonly affect patients between the ages of 20 to 40 years. Ameloblastomas are uncommon in children younger than ten years. Males and females are equally affected. Rizzitelli A et al. 11 conducted a population-based study of malignant ameloblastoma to determine it’s incidence rate and absolute survival. They looked at 293 patients across the United States and found that the overall incidence rate of malignant ameloblastoma was 1.79 per 10 million persons/year. The rate of incidence was higher in males than females and also higher in the black versus white population. They also found that malignant ameloblastoma, comprising the two types, metastasizing ameloblastoma, and ameloblastic carcinoma, represents 1.6 to 2.2% of all odontogenic tumors. Their findings confirmed previous epidemiologic research, which showed the male to female ratio to be between 2.3 and 5 12.

Several histologic types of ameloblastoma are described in the literature including plexiform, follicular, basal cell, granular cell, clear cell, and acanthomatous. The plexiform and follicular types are the most common patterns 8. The follicular ameloblastoma (Figure 4 E) is further subdivided into acanthomatous, granular, spindle cell, and basal cell types. Ameloblastomas are classified by the most predominant histologic pattern present 13. In the plexiform pattern (see Figure 2 A), the connective tissue is surrounded by epithelial components while in the follicular pattern, the epithelium is surrounded by the connective tissue 7. The basal cell-like pattern (Figure 4 F) is apparently benign and tends to grow in an island-like pattern. The basaloid appearing cells tend to stain basophilic deeply. The cells in the central portion may be polyhedral to spindle shaped; stellate reticulum-like areas are notably absent 14. It is reported that tumors with follicular and acanthomatous histology have the highest and lowest recurrence rates, respectively 15.

In a literature review 16, the most common pattern of orbital ameloblastoma was follicular (48.1%), followed by plexiform (37%), basal cell-like (7.4%), and mixed ( 7.4%). In males, the most common tumor pattern was plexiform (50%), followed by follicular (35%), mixed (10%), and basal cell-like (5%). In females, the most prevalent type was follicular (6/7; 85.7%) followed by basal cell-like (14.3%). Plexiform pattern was not reported in female cases 16.

The causative mutation leading to ameloblastoma is the activation of FGFR2, BRAF, and RAS that can lead to the dysregulation of the MAPK signaling as a pivotal step in the pathogenesis of the tumor 17. It seems that different mutations are involved in maxillary and mandibular ameloblastoma, and this may partially explain the higher aggressive behavior of the maxillary type. McClary et al. 8 in their review, proposed that specifically smoothened (SMO) and RAS were the most prevalent mutated genes in maxillary ameloblastoma, while, BRAF was the most one in the mandibular counterpart.

Four distinct growth variants of ameloblastoma are recognized in the current 2005 WHO classification for head and neck tumors 18:

- Peripheral ameloblastoma, in which tumor is extraosseous and shows continuity with the oral mucosal stratified squamous epithelium,

- Unicystic ameloblastoma, in which a single cystic intraosseous growth pattern is observed grossly and radiographically,

- Solid or multicystic ameloblastoma, in which invasive tumor permeates bone marrow spaces and may show multicystic foci, and

- Desmoplastic ameloblastoma, an infiltrative intraosseous tumor dominated by the stromal component, radiographically reminiscent of a fibro-osseous lesion 19.

The intraosseous ameloblastomas are collectively termed “central ameloblastomas” 19. Approximately 80 % of central ameloblastomas arise in the mandible, but involvement of the maxilla is rare 20. Various histologic patterns are recognized in unicystic, solid/multicystic, and peripheral growth variants of ameloblastoma.

The benign histology and indolent behavior of ameloblastoma have led to a traditionally conservative surgical approach. However, while histologically benign, ameloblastoma, particularly the solid/multicystic variant, is characterized by locally aggressive spread with up to 90 % recurrence rate following conservative excision 13. Prolonged tumor duration and multiple recurrences have been associated with metastases of the histologically benign-appearing ameloblastoma, so called “metastasizing ameloblastoma” 21. Additionally, long-standing and recurrent ameloblastoma has been shown to occasionally transform into an aggressive ameloblastic carcinoma 22.

Recent data from several centers suggests that the initial surgical management approach and histologic growth pattern are the most important prognostic determinants in ameloblastoma 22, 23. Radical surgery can achieve recurrence rates as low as 0–4.5 % and wider resection may be required for ameloblastomas with more aggressive histologic patterns, such as follicular, granular cell, and acanthomatous variants 23. Despite these findings, the debate on an ideal management that would achieve cure without unnecessary compromise of cosmesis and function, is ongoing. The continued controversy stems in part from the outcome data generated by the small retrospective case series without sufficient patient follow-up 24.

Figure 1. Ameloblastoma histology

[Source 25]Figure 2. Ameloblastoma histology – Histologic patterns in solid/multicystic ameloblastoma. A) Plexiform ameloblastoma demonstrates interweaving fascicles of neoplastic cells with hyperchromatic columnar nuclei, polarized away from the basement membrane (“reversed polarity”, “piano-key” arrangement). B) Islands of granular ameloblastoma demonstrate central stellate reticulum-like cells with abundant eosinophilic granular cytoplasm.

Figure 3. Ameloblastoma histology – Histologic patterns in solid/multicystic ameloblastoma. C) Acanthomatous ameloblastoma shows squamous-type differentiation of the central stellate reticulum-like cells, while maintaining the reverse polarization of the nuclei in columnar cells lining the nests. D) Desmoplastic ameloblastoma shows islands of odontogenic epithelium in abundant desmoplastic stroma.

Figure 4. Ameloblastoma histology – Histologic patterns in solid/multicystic ameloblastoma. E) Follicular ameloblastoma islands demonstrate peripheral columnar cells exhibiting reversal of polarity and central stellate-reticulum like cells with cystic degeneration. F) Basal cell type ameloblastoma islands contain basaloid cells with scant cytoplasm and peripheral palisading, reminiscent of basal cell carcinoma.

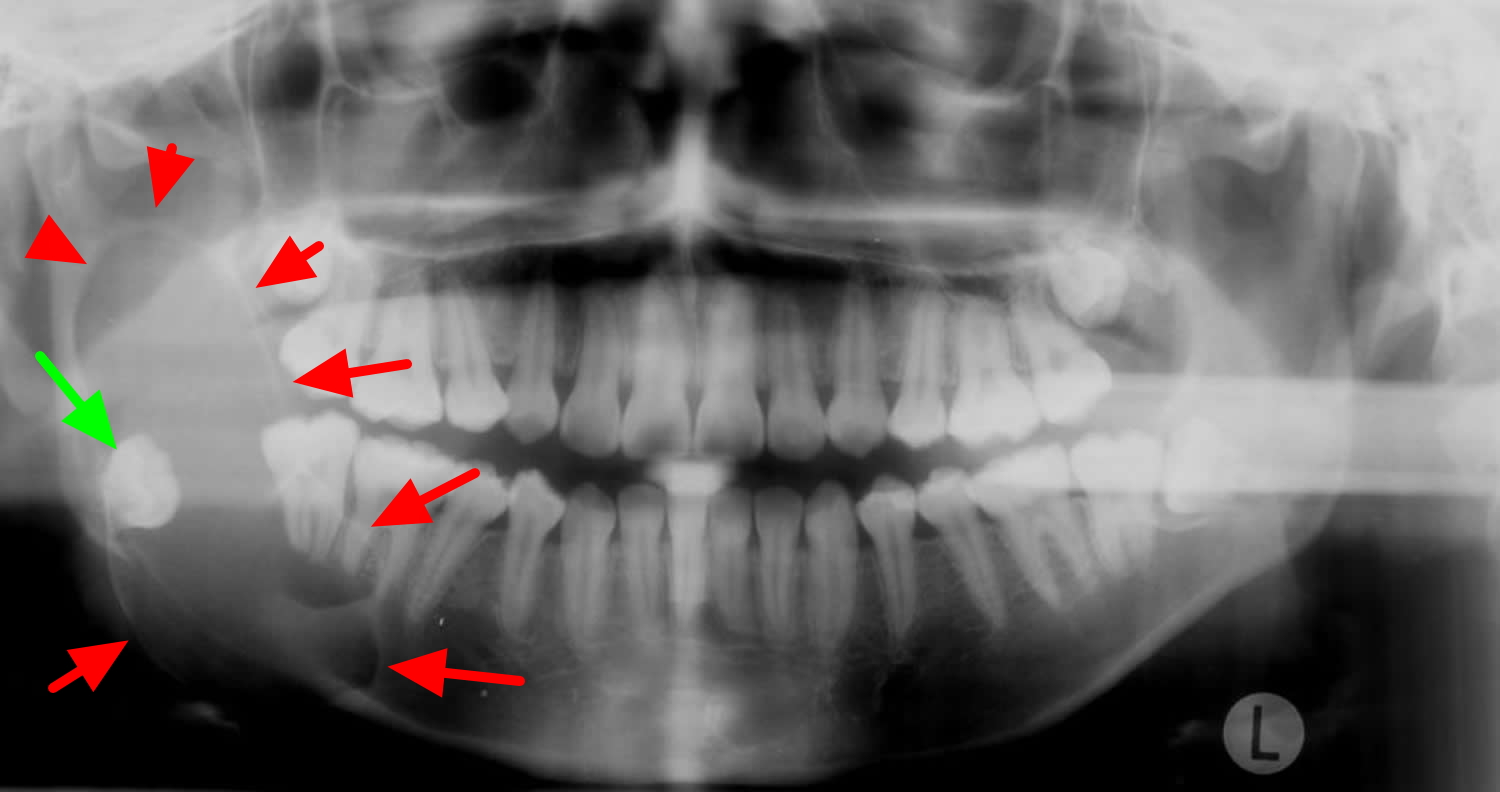

Figure 5. Ameloblastoma on OPG (orthopantomography) – there is a large lucent lesion expanding the right ramus of the mandible (red arrows). It is associated with the crown of the unerrupted right mandibular 3rd molar (green arrow) and has features most in keeping with an ameloblastoma

Figure 6. Ameloblastoma CT scan

Acanthomatous ameloblastoma

Acanthomatous ameloblastoma type of ameloblastoma is one of the rarest types. Acanthomatous ameloblastoma is usually seen in older aged human population and most commonly reported in canine region of dogs in literature 26. Acanthomatous ameloblastoma is a benign tumor, but is locally aggressive and frequently invades the alveolar bone or recurs after marginal surgical excision. It is classified as an ameloblastoma; however controversies exist as to whether this tumor should be classified as a basal cell carcinoma, epulis or an odontal origin tumor 27.

Patients may complain or present with the history of a slow growing mass, malocclusion, loose teeth or more rarely paresthesia and pain, however many lesions are detected incidentally on radiographic studies in asymptomatic patients. The lesions usually progress slowly but if left untreated can resorb the cortical plate and extend into adjacent tissue. In one case the patient only reported regarding slowly progressive swelling and difficulty in mastication.

The treatment of choice is complete surgical resection. If possible, conservative surgery can be used if an assured complete removal can be performed 28. In addition to low sensitivity of this neoplasm, the intraosseous location of the ameloblastoma prevents the use of radiotherapy as an effective therapeutic option because radiation induces the potential development of secondary tumors. Therefore, in all types of ameloblastomas, a thorough long term clinical and radiographic follow up is always recommended 29.

Ameloblastic carcinoma

The World Health Organization (WHO) classified malignant ameloblastoma into two types: metastasizing ameloblastoma and ameloblastic carcinoma 30.

- Metastasizing ameloblastoma

- Metastasizing ameloblastoma histologically resembles the benign ameloblastoma but shows metastatic spread to distant sites

- Ameloblastic carcinoma

- Ameloblastic carcinoma exhibits malignant features on histology

- Can be further subdivided into two subtypes:

- Primary ameloblastic carcinoma: arises de novo (from Latin meaning “anew”)

- Secondary ameloblastic carcinoma is the eventual result of malignant transformation of a previously diagnosed benign ameloblastoma

Malignant ameloblastomas have only been reported in small case series or case reports and no population-based studies of its incidence have been reported. Metastasizing ameloblastoma is often considered to account for 2% of benign ameloblastoma 31, but the actual incidence rate is likely to be less 32. The exact incidence rate of ameloblastic carcinoma is unknown and only approximately 100 cases have been reported in the literature 33.

According to the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) data, the overall incidence rate of malignant ameloblastoma was 1.79 per 10 million persons per year with male and black population predominance 11. The incidence rate increased as individual got older and elderly patients who received a diagnosis of malignant ameloblastoma were nearly 10-times more likely to die than children and young adults.

The majority of malignant ameloblastomas occurred in males rather than females and this results confirmed previous studies showing the male to female ratio to be between 2.3 and 5 34. The cause for this increased incidence of malignant ameloblastomas in males compared with females has not been investigated or reported, and remains unknown. The incidence rate of developing a malignant ameloblastoma was higher in the black population. It remains to be explored if this difference is determined by genetic or environment factors.

Ameloblastoma most commonly affects the mandible and maxilla, rarely other sites 35. The SEER database only recorded the site of ameloblastomas as either the mandible or the “bones of skull”. Hence, the latter was assumed to comprise mostly maxillary tumors. This results was surprising as the literature reports the mandible as the preferred site of disease development 36. However, most case reports published to date are from India, Japan and China. It is thus possible that this anatomical distribution imbalance is a unique feature of the U.S. population.

Ameloblastoma causes

Ameloblasts are of ectodermal origin and derived from oral epithelium 3. The cells are only present during tooth development that deposit tooth enamel (the hard, outer covering that protects the teeth), which forms the outer surface of the crown. Ameloblasts become functional only after odontoblasts form the primary layer of dentin (the layer beneath enamel). The cells eventually become part of the enamel epithelium and eventually undergo apoptosis (cell death) before or after tooth eruption.

There exist deposits of these cells in the structures in and around the tooth, termed cell rests of Malessez and cell rests of Serres 3. Current thought is that ameloblastomas can arise from either the cells mentioned above or other cells of ectodermal origin, such as those associated with the enamel organ.

Approximately 80% occur in the mandible and the other 20% in the maxilla.

Advanced next generation sequencing analyses identified the high frequency of BRAF V600E and SMO L412F mutations in ameloblastoma 37. In 2018, Gültekin et al 37. reported novel somatic mutation of oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes in addition to BRAF and SMO mutations. Using cell culture model with established ameloblastoma cell lines, Nakao et al 38 reported that fibroblast growth factor (FGF) −7 and −10 stimulates ameloblastoma proliferation. Sathi et al 39 reported that secreted frizzled related protein‐2 (sFRP-2) is involved in the proliferation of ameloblastoma cells. These reports implicate the mitogen‐activated protein kinase pathway and/or sonic hedgehog signaling pathway in the pathogenesis of ameloblastoma cells 40. Heikinheimo et al 41 reported a targeted microarray study focusing on the mRNA expression of 588 cancer‐related genes. Although a certain subset of genomic sequence information or specific gene expression regarding ameloblastoma patients have been explored, the comprehensive gene expression profiles related to ameloblastoma remains largely unknown. Additionally, the relationship between gene expression changes and genomic alterations in ameloblastoma is still obscure and remain poorly understood 42.

Types of ameloblastoma

Ameloblastoma is classified, according to World Health Organization (WHO) and the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), 2003, as a benign tumor with odontogenic epithelium, mature fibrous stroma and without odontogenic ectomesenchyme 1. Ameloblastoma is further classified into:

- Solid or multicystic ameloblastoma

- Extraosseous peripheral ameloblastoma

- Desmoplastic ameloblastoma

- Unicystic ameloblastoma

Solid or Multicystic Ameloblastoma

The solid or multicystic ameloblastoma is a benign epithelial odontogenic tumor of the jaws 43. It is slow-growing locally aggressive and accounts for about 10% of all odontogenic tumors in the jaw 5. Solid multicystic ameloblastoma occur as growths arising from remnants of odontogenic epithelium, exclusively from rests of the dental lamina. solid multicystic ameloblastomas may also arise as a result of neoplastic changes in the lining or wall of a nonneoplastic odontogenic cyst, in particular dentigerous and odontogenic keratocysts 44. Signaling pathway such as WNT, Akt and growth factors like fibroblast growth factor play a pivotal role in the pathogenesis of solid type of ameloblastoma. Proteins mainly bone morphogenic protein ameloblastin, enamel matrix proteins calretinin, syndecan-1 and matrix metalloproteinases also play an important contribution in the etiopathogenesis. Tumor suppressor genes p53, p63 and p73 bring about molecular changes in the pathogenesis of ameloblastoma. p53 plays an important role in the differentiation and proliferation of odontogenic epithelial cells. Matrix metalloproteinases, triggers mitogens to be released, leading to the proliferation of ameloblastoma cells 45.

Mostly solid multicystic ameloblastoma is diagnosed in young adults, with a median age of 35 years and no gender predilection. About 80% of ameloblastomas occurs in the mandible 46, frequently in the posterior region 5. The lesions more often progresses slowly, but are locally invasive and infiltrates through the medullary spaces and erodes cortical bone. If left untreated, they resorb the cortical plate and extend into adjacent tissue. Crepitation or eggshell crackling might be elicited posterior maxillary tumors might obliterate the maxillary sinus and consequently extend intracranial 47.

Radiographically solid multicystic ameloblastomas show an expansile, radiolucent, multiloculated cystic lesion, with a characteristic “soap bubble-like” appearance. Other findings include cystic areas of low attenuation with scattered regions representing soft tissue components. Thinning and expansion of the cortical plate with erosion through the cortex is elicited, with the associated unerupted tooth displaced and resorption of the roots of adjacent teeth common 48.

Six histopathologic subtypes of solid ameloblastoma includes follicular, plexiform, acanthomatous, basal cell, granular and DA. Mixtures of different histological patterns are commonly observed, and the lesions are frequently classified based on the predominant pattern present. The follicular pattern type has the highest recurrence rate of 29.5% and acanthomatous type having the least recurrence rate of 4.5%, and the rate of recurrence depends on the histologic subtypes. The epithelial component of the neoplasm proliferates in the form of Islands, strands and cords within the moderately to densely collagenized connective tissue stroma. A prominent budding growth pattern with small, rounded extensions of epithelium projecting from larger islands, recapitulates the various stages of enamel organ formation. The classical histological pattern of ameloblastoma described by Vickers and Gorlin is characterized by peripheral layer of tall columnar cells with hyperchromasia, reverse polarity of the nuclei and sub-nuclear vacuole formation 49.

Follicular type is composed of many small islands of peripheral layer of cuboidal or columnar calls with reversely polarized nucleus. Cyst formation is relatively common in follicular type. The term plexiform refers to the appearance of anastomosing islands of odontogenic epithelium, with double rows of columnar cells in back to back arrangement. In acanthomatous type, the cells occupying the position of stellate reticulum undergo squamous metaplasia, with keratin pearl formation in the center of tumor islands. In granular cell ameloblastoma, cytoplasm of stellate reticulum-like cells appear coarse granular and eosinophilic. Basal cell type, the epithelial tumor cells are less columnar and arranged in sheets. Desmoplastic variant is composed of the dense collagen stroma, which appears hypocellular and hyalinized 49.

Other histological types are papilliferous-keratotic type, clear cell type, and mucous cell differentiation type. Solid multicystic ameloblastomas contain clear, periodic-acid Schiff positive cells most often localized to the stellate reticulum-like areas of follicular solid multicystic ameloblastoma 44. Keratoameloblastoma consists partly of keratinizing cysts and partly of tumor islands with papilliferous appearance. Mucous cell type of ameloblastoma shows focal mucous cell differentiation, with vacuolated mucous cells 50.

The main modality of treatment is surgery, with wide resection recommended due to the high recurrence rate of solid or multicystic ameloblastomas. The recurrence rate after resection is 13-15%, as opposed to 90-100% after curettage 51. Recommend a margin of 1.5-2 cm beyond the radiological limit is implicated to ensure all microcysts are removed 52.

Peripheral Ameloblastoma

The peripheral ameloblastoma is defined as an ameloblastoma that is confined to the gingival or alveolar mucosa. It infiltrates the surrounding tissues, mostly the gingival connective tissue, but it does not involve the underlying bone 53. The peripheral ameloblastoma arises from remnants of the dental lamina, the so-called “glands of Serres,” odontogenic remnants of the vestibular lamina, pluripotent cells in the basal cell layer of the mucosal epithelium and pluripotent cells from minor salivary glands 54.

The peripheral ameloblastoma is an exophytic growth restricted to the soft tissues overlying the tooth-bearing areas of the jaws, the initial diagnosis often mistaken for fibrous epulis. In the majority of cases, there is no radiological evidence of bone involvement, but a superficial bone erosion known as cupping or saucerization may be detected at surgery. The overall average age is 52.1 years, slightly higher for males than for females. The male/female ratio is 1.9 : 1, as opposed to 1.2 : 1 for the solid type. The maxilla/mandible ratio is 1 : 2.6. The mandibular premolar region accounts for 32.6% and is the commonest site 55. Histologically same patterns are as in solid type, with a common type being acanthomatous 49. Differential includes peripheral reactive lesions such as pyogenic granuloma, epulis, papilloma, fibroma, peripheral giant-cell granuloma, peripheral odontogenic fibroma, peripheral-ossifying fibroma, Baden’s odontogenic gingival epithelial hamartoma, and basal cell carcinoma 55.

The peripheral ameloblastoma is mostly treated with a wide local excision. 9% of recurrence following treatment has been reported, though malignant transformation is rare, metastasis has also been reported 56.

Desmoplastic Ameloblastoma

Desmoplastic ameloblastoma was first reported by Eversole et al. in 1984 and was recently included in the WHO’s classification of head and neck tumors (WHO-2005) 57. This tumor is characterized by an unusual histomorphology, including extensive stromal collagenization or desmoplasia, leading to the proposed term ameloblastoma with pronounced desmoplasia or desmoplastic ameloblastoma 58.

Radiographically it produces mixed radiolucent – radioopaque lesion with diffuse border that indicates that the tumor is more aggressive than other variants of ameloblastoma 59. Mixed radiologic appearance expresses the infiltrative pattern of the tumor and when the desmoplastic ameloblastoma infiltrates the bone marrow spaces, remnants of the original nonmetaplastic or nonneoplastic bone were found to remain in the tumor tissue. The infiltrative behavior of the desmoplastic ameloblastoma explains one of the characteristic features of the tumor, the ill-defined border 44.

The desmoplastic ameloblastoma also appears as a poorly defined, mixed, radiolucent-radiopaque lesion mimicking a benign fibro-osseous lesion, especially when evaluating panoramic and periapical radiographs 60. Histologically desmoplastic ameloblastoma appears as irregularly shaped odontogenic epithelial islands surrounded by a narrow zone of loose-structured connective tissue embedded in desmoplastic stroma 61.

About 15.9% rate of recurrence has been reported in desmoplastic ameloblastoma cases treated by enucleation and/or curettage, with an average recurrence period of 36.9 months 60. The majority of desmoplastic ameloblastoma cases reported treated by resection, most likely due to ill-defined borders, consequently suggesting an infiltration process and aggressive biological behavior 62.

Unicystic Ameloblastoma

Unicystic ameloblastoma represents an ameloblastoma variant, presenting as a cyst that show clinical and radiologic characteristics of an odontogenic cyst. In histologic examination shows a typical ameloblastomatous epithelium lining part of the cyst cavity, with or without luminal and/or mural tumor proliferation. In 1977, Robinson and Martinez 63 first used the term “unicystic ameloblastoma” but it was also named in the second edition of the international histologic classification of odontogenic tumors by the WHO as “cystogenic ameloblastoma” 47.

Five to 15% of all ameloblastomas are of the unicystic type. Unicystic ameloblastoma with an unerupted tooth occurs with a mean age of 16 years as opposed to 35 years in the absence of an unerupted tooth. The mean age is considerably lower than that for solid/multicystic ameloblastoma with no gender predilection 47. Unicystic ameloblastoma is a prognostically distinct entity with a recurrence rate of 6.7-35.7%, and the average interval for recurrence is approximately 7 years.

Three pathogenic mechanisms for the evolution of unicystic ameloblastoma: Reduced enamel epithelium, from dentigerous cyst and due to cystic degeneration of solid ameloblastoma 64.

Six radiographic patterns are identified for unicystic ameloblastoma, ranging from well-defined unilocular to multilocular ones. Comparing unilocular and multilocular variants, there is an apparent predominance of a unilocular configuration in all studies of unicystic ameloblastoma, especially in cases associated with impacted teeth 65. Unicystic ameloblastoma might mimic other odontogenic cysts clinically and radiographically.

Histopathological classification of unicystic ameloblastomas are 66:

- Luminal unicystic ameloblastoma

- Luminal and intraluminal unicystic ameloblastomas

- Luminal, intraluminal, and intramural unicystic ameloblastomas

- Luminal and intramural unicystic ameloblastomas.

Treatment of unicystic ameloblastoma includes both radical and conservative surgical excision, curettage, chemical and electrocautery, radiation therapy or combination of surgery and radiation.

Ameloblastoma prognosis

Generally, prognosis of maxillary ameloblastoma is worse than the mandibular type due to its more recurrence rate, invasion to vital structures, and more advanced stages at the time of diagnosis due to lack of pain or other harbinger symptoms 67. Orbital ameloblastoma has an additional tendency to be transformed into the carcinomatous variant. Hence, the prognosis of orbital ameloblastomas in line with tumors involving skull base seems to be the worst 68.

Ameloblastoma is, in essence, a lifelong disease. Although most tumors recur within 5 years of original diagnosis, late recurrences are not uncommon, and were seen in 23 % of the patients in the current study. While neglected and recurrent ameloblastoma can cause significant morbidity, mortality is extremely rare and is seen typically in a setting of maxillary ameloblastoma extending into the cranium 22. The rare metastasizing ameloblastoma and ameloblastic carcinoma, each described in up to 2 % of patients with ameloblastoma, can also infrequently lead to mortality 22.

In a review, survival among all cases was 13.47 ± 12.81 years and among different patterns of tumor varied. Among the cases with more than five years of survival (five cases died before 5 years), survival was 16.4 ± 15.1 years in follicular and 18.1 ± 9.9 years in plexiform types, respectively 16.

Maxillary ameloblastoma is a locally aggressive neoplasm so that physicians must be alert to the biologic behavior of this tumor to detect any invasion to critical structures such as orbit and cranium. Meticulous patient follow-up with regular clinical examinations and diagnostic work-up (especially MRI) for timely detection of any invasion or recurrence of this tumor.

Orbital ameloblastoma causes significant morbidity and mortality. In extensive and longstanding tumors, a multidisciplinary approach is required that may span several specialties i.e. neurosurgery, head and neck surgery/otolaryngology, maxillofacial surgery, ophthalmology, and radiotherapy. This joint effort may take several years to handle the condition to the extent that a recurrence may be detected as late as three decades since the initial diagnosis.

Ameloblastoma signs and symptoms

Ameloblastomas typically occur as hard, painless lesions near the angle of the mandible in the region of the 3rd molar tooth (48 and 38) although they can occur anywhere along the alveolus of the mandible (80%) and maxilla (20%). When the maxilla is involved, the tumor is located in the premolar region and can extend up into the maxillary sinus.

Although benign, it is a locally aggressive neoplasm with a high rate of recurrence. Approximately 20% of cases are associated with dentigerous cysts and unerupted teeth.

Ameloblastomas do not usually become malignant. There is evidence that tissue is more likely to become malignant if the condition reoccurs after surgery.

Ameloblastoma diagnosis

A definitive diagnosis of ameloblastoma is with a surgical biopsy, which shows characteristic histologic findings. Ameloblastoma can show up either in a regular x-ray or in an MRI imaging study. Radiographic studies play a cardinal role in pre-operative and post-operative management of patients with ameloblastoma. Dental X-rays (orthopantomography) typically demonstrate a lytic lesion with scalloped margins or a “soap bubble” appearance, which can be associated with resorption of tooth roots and impacted teeth 13. Orthopantomography can help detect asymptomatic ameloblastomas. CT has emerged as the most useful diagnostic imaging modality, demonstrating expansile, lytic, unilocular or multilocular cystic lesions with or without soft tissue extension. In addition to CT, MRI has been recommended in evaluation of patients with maxillary ameloblastoma, because of its potential to more precisely evaluate the soft tissue extent of the lesion 13.

Ameloblastoma radiology

Ameloblastomas originated within bone are mostly diagnosed incidentally in pan-tomography imaging or plain films. The routine radiographic picture is the ‘soap bubble’ appearance 69. Plain X-ray imaging has limited sensitivity and specificity to evaluate tumor invasion. CT can be useful in detecting bone extensions, and MRI provides better resolution in detecting soft tissue extensions and tumor margins, particularly in maxillary ameloblastoma 70. Particularly, in diagnosing the desmoplastic type, the MRI plays a pivotal role due to poor defined soft tissue extensions in addition to the similarity to fibro-osseous lesions 71.

Figure 7. Ameloblastoma MRI T2 (A: Coronal view showing a round enhanced mass in the inferior orbit. B: Axial view.)

Ameloblastoma treatment

In treating ameloblastoma, the mainstay is radical surgery including en-bloc resection 8. Concerning the management of mandibular ameloblastoma, some authors maintain that partial resection or curettage is enough, however, these modalities are not curative and are not standard of care now 3. Reported recurrence rates are up to 70%, with incomplete resection being the most common reason for the high recurrence rate.

Radiotherapy when employed as the first line treatment has a recurrence rate as high as 70% 15. One study reviewed ten patients with ameloblastomas treated with megavoltage irradiation and concluded that ameloblastoma was not an inherently radio-resistant tumor and that properly applied megavoltage irradiation had a useful role in the management 72. Even more, there is a study in which all the patients were reported to experience recurrence following the sole radiation therapy 73. Hence, radiotherapy alone is not wise in the management of ameloblastoma. However, radiotherapy has been shown to be effective in decreasing the tumor size and pain palliation. Therefore, radiotherapy can still be placed in the therapeutic arsenal for cases with recurrence, unresectable tumors, and patients who are unable to undergo surgery for any reason 8.

The role of chemotherapy in the management of ameloblastoma is an issue of debate. Some authors suggest that ameloblastoma may be sensitive to platinum-based agents. Some 74, 75, 76 report promising results by this modality for advanced cases while others5, 12, 23 maintain that this method is not effective in reducing tumor size or even palliation. In the literature, there are sparse instances of molecular-targeted therapy that should be further examined in future studies. Kaye et al. 77 reported a patient with multiple recurrent ameloblastoma in the mandible and metastatic ameloblastoma in the lung who harbored a BRAF V600E mutation. The patient was treated with a combination of dabrafenib (BRAF inhibitor) and trametinib (MEK inhibitor) and achieved a dramatic response after 8 weeks of therapy. Additionally, in another study, reducing the tumor size using vismodegib (SMO inhibitor) was reported 78.

Ameloblastoma surgery

In the maxillary type, morphology, histopathology, and extension of the tumor are crucial in decision-making. The recommended safe margin for unicystic ameloblastoma, multicystic ameloblastoma, and ameloblastic carcinoma is proposed to be 1–1.5, 1.5–2, and 2–3 cm, respectively 79.

Regarding the management of maxillary ameloblastoma involving the orbit, the following strategies can be used alone or in combination with each other 80:

- In tumors not involving orbital fat/soft tissue, a complete resection of the mass may suffice.

- For cases with orbital floor involvement, total maxillectomy is reasonable.

- In cases with orbital soft tissue involvement, orbital exenteration is inevitable.

- Skull base invasion, if occurred, necessitates resection of anterior skull base.

Recurrence after partial resection of the maxillary ameloblastoma results in a tumor with more aggressive behavior with higher mortality rates (33–60%) 81. To reduce the recurrence rate, it is wise to perform the MRI and CT for more investigation of tumor extension, preoperatively 8.

Ameloblastic carcinoma treatment

Ameloblastic carcinoma treatment is generally via surgical resection with 2 to 3 cm margins. Concurrent chemoradiotherapy is an option after resection for positive margins or perineural invasion. In malignant ameloblastoma, surgical resection with 1 to 2 cm margins is usually the treatment modality of choice, and no chemotherapy or radiotherapy is generally required 82.

Since malignant ameloblastoma is typically a slow-growing tumor, more active treatment approaches such as chemo or radiotherapy may not be necessary. Close patient follow-up for a minimum of five years is necessary to monitor for recurrence 3 .

- Masthan, K. M., Anitha, N., Krupaa, J., & Manikkam, S. (2015). Ameloblastoma. Journal of pharmacy & bioallied sciences, 7(Suppl 1), S167–S170. https://doi.org/10.4103/0975-7406.155891[↩][↩]

- Brazis PW, Miller NR, Lee AG, Holliday MJ. Neuro-ophthalmologic aspects of ameloblastoma. Skull Base Surg. 1995;5(4):233–244. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1058921. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1656531/pdf/skullbasesurg00026-0046.pdf[↩]

- Palanisamy JC, Jenzer AC. Ameloblastoma. [Updated 2021 Jul 5]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK545165[↩][↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Masthan K.M., Anitha N., Krupaa J., Manikkam S. Ameloblastoma. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2015;7(Suppl 1):S167–S170. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4439660/[↩]

- Mendenhall WM, Werning JW, Fernandes R, Malyapa RS, Mendenhall NP. Ameloblastoma. Am J Clin Oncol. 2007 Dec;30(6):645-8. doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e3181573e59[↩][↩][↩]

- Gold L. Biologic behavior of ameloblastoma. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 1991;3(1):21–27.[↩]

- Morgan P.R. Odontogenic tumors: a review. Periodontol 2000. 2011;57(1):160–176. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21781186[↩][↩]

- McClary A.C., West R.B., McClary A.C. Ameloblastoma: a clinical review and trends in management. Eur Arch Oto-Rhino-Laryngol. 2016;273(7):1649–1661. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25926124[↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Chowdhury M.O.R., Islam S., Chowdhury W., Haque M. Extensive ameloblastoma of the mandible. TAJ J Teach Assoc. 2002;15(2):93–95.[↩]

- Pulmonary metastasis of ameloblastoma: case report and review of the literature. Henderson JM, Sonnet JR, Schlesinger C, Ord RA. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1999 Aug; 88(2):170-6. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10468461/[↩]

- Rizzitelli, A., Smoll, N. R., Chae, M. P., Rozen, W. M., & Hunter-Smith, D. J. (2015). Incidence and overall survival of malignant ameloblastoma. PloS one, 10(2), e0117789. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0117789[↩][↩]

- Mahmoud SAM, Amer HW, Mohamed SI. Primary ameloblastic carcinoma: literature review with case series. Pol J Pathol. 2018;69(3):243-253. doi: 10.5114/pjp.2018.79544[↩]

- McClary AC, West RB, McClary AC, Pollack JR, Fischbein NJ, Holsinger CF, Sunwoo J, Colevas AD, Sirjani D. Ameloblastoma: a clinical review and trends in management. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2015 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25926124[↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Kessler H.P. Intraosseous ameloblastoma. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2004;16(3):309–322. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18088733[↩]

- Reichart P.A., Philipsen H.P., Sonner S. Ameloblastoma: biological profile of 3677 cases. Eur J Cancer B Oral Oncol. 1995;31b(2):86–99. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7633291[↩][↩]

- Abtahi M-A, Zandi A, Razmjoo H, et al. Orbital invasion of ameloblastoma: A systematic review apropos of a rare entity. Journal of Current Ophthalmology. 2018;30(1):23-34. doi:10.1016/j.joco.2017.09.001. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5859465/[↩][↩][↩]

- Brown N.A., Betz B.L. Ameloblastoma: a review of recent molecular pathogenetic discoveries. Biomarkers Cancer. 2015;7(Suppl 2):19–24. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4597444/[↩]

- Milman T, Ying G-S, Pan W, LiVolsi V. Ameloblastoma: 25 Year Experience at a Single Institution. Head and Neck Pathology. 2016;10(4):513-520. doi:10.1007/s12105-016-0734-5. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5082058/[↩]

- Barnes L, Eveson JW, Reichart P, Sidransky D. World Health Organization classification of tumors. Pathology and genetics of head and neck tumours. Lyon: IARC Press; 2005.[↩][↩]

- Reichart PA, Philipsen HP, Sonner S. Ameloblastoma: biological profile of 3677 cases. Eur J Cancer Part B Oral Oncol. 1995;31B:86–99. doi: 10.1016/0964-1955(94)00037-5. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7633291[↩]

- Luo DY, Feng CJ, Guo JB. Pulmonary metastases from an ameloblastoma: case report and review of the literature. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2012;40:e470–e474. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2012.03.006. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22507293[↩]

- Zwahlen RA, Grätz KW. Maxillary ameloblastomas: a review of the literature and of a 15-year database. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2002;30:273–279. doi: 10.1016/S1010-5182(02)90317-3. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12377199[↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Sham E, Leong J, Maher R, Schenberg M, Leung M, Mansour AK. Mandibular ameloblastoma: clinical experience and literature review. ANZ J Surg. 2009;79:739–744. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2009.05061.x. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19878171[↩][↩]

- de Almeida R AC, Andrade ES, Barbalho JC, Vajgel A, Vasconcelos BC. Recurrence rate following treatment for primary multicystic ameloblastoma: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2016;45:359–367. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2015.12.016. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26792147[↩]

- Amzerin M, Fadoukhair Z, Belbaraka R, et al. Metastatic ameloblastoma responding to combination chemotherapy: case report and review of the literature. Journal of Medical Case Reports. 2011;5:491. doi:10.1186/1752-1947-5-491. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3198715/[↩]

- Ugrappa S, Jain A, Fuloria NK, Fuloria S. Acanthomatous Ameloblastoma in Anterior Mandibular Region of a Young Patient: A Rare Case Report. Annals of African Medicine. 2017;16(2):85-89. doi:10.4103/aam.aam_51_16. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5452712/[↩]

- Acanthomatous ameloblastoma in dogs treated with intralesional bleomycin. Kelly JM, Belding BA, Schaefer AK. Vet Comp Oncol. 2010 Jun; 8(2):81-6. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20579320/[↩]

- Schafer DR, Thompson LDR, Smith BC, Wenig BM. Primary ameloblastoma of the sinonasal tract. Cancer. 1998;82(4):667–674. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9477098[↩]

- LR Olieira, BH Matos, PR Dominguete, VA Zorgetto, AR Silva. Ameloblastoma: Report of two cases and a brief literature review. Int.J. Odontostomat. 2011;5(3):293–299.[↩]

- Sciubba JJ, Eversole LR, Slootweg PJ (2005) Odontogenic / ameloblastic carcinomas In: Barnes L, Eveson J, Reichart PA, Sidransky D, editors. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours: Head and Neck Tumours. Lyon: IARC Press; pp. 286–295.[↩]

- Verneuil A, Sapp P, Huang C, Abemayor E. Malignant ameloblastoma: classification, diagnostic, and therapeutic challenges. Am J Otolaryngol. 2002 Jan-Feb;23(1):44-8. doi: 10.1053/ajot.2002.28769[↩]

- Houston G, Davenport W, Keaton W, Harris S. Malignant (metastatic) ameloblastoma: report of a case. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1993 Oct;51(10):1152-5; discussion 1156-7. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(10)80458-6[↩]

- Kar, I. B., Subramanyam, R. V., Mishra, N., & Singh, A. K. (2014). Ameloblastic carcinoma: A clinicopathologic dilemma – Report of two cases with total review of literature from 1984 to 2012. Annals of maxillofacial surgery, 4(1), 70–77. https://doi.org/10.4103/2231-0746.133070[↩]

- Li, J., DU, H., Li, P., Zhang, J., Tian, W., & Tang, W. (2014). Ameloblastic carcinoma: An analysis of 12 cases with a review of the literature. Oncology letters, 8(2), 914–920. https://doi.org/10.3892/ol.2014.2230[↩]

- Yoon HJ, Jo BC, Shin WJ, Cho YA, Lee JI, Hong SP, Hong SD. Comparative immunohistochemical study of ameloblastoma and ameloblastic carcinoma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2011 Dec;112(6):767-76. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2011.06.036[↩]

- Casaroto AR, Toledo GL, Filho JL, Soares CT, Capelari MM, Lara VS. Ameloblastic carcinoma, primary type: case report, immunohistochemical analysis and literature review. Anticancer Res. 2012 Apr;32(4):1515-25.[↩]

- Gültekin, S. E., Aziz, R., Heydt, C., Sengüven, B., Zöller, J., Safi, A. F., Kreppel, M., & Buettner, R. (2018). The landscape of genetic alterations in ameloblastomas relates to clinical features. Virchows Archiv : an international journal of pathology, 472(5), 807–814. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00428-018-2305-5[↩][↩]

- Nakao, Y., Mitsuyasu, T., Kawano, S., Nakamura, N., Kanda, S., & Nakamura, S. (2013). Fibroblast growth factors 7 and 10 are involved in ameloblastoma proliferation via the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. International journal of oncology, 43(5), 1377–1384. https://doi.org/10.3892/ijo.2013.2081[↩]

- Sathi GA, Inoue M, Harada H, Rodriguez AP, Tamamura R, Tsujigiwa H, Borkosky SS, Gunduz M, Nagatsuka H. Secreted frizzled related protein (sFRP)-2 inhibits bone formation and promotes cell proliferation in ameloblastoma. Oral Oncol. 2009 Oct;45(10):856-60. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2009.02.001[↩]

- Brown, N. A., & Betz, B. L. (2015). Ameloblastoma: A Review of Recent Molecular Pathogenetic Discoveries. Biomarkers in cancer, 7(Suppl 2), 19–24. https://doi.org/10.4137/BIC.S29329[↩]

- Heikinheimo K, Jee KJ, Niini T, Aalto Y, Happonen RP, Leivo I, Knuutila S. Gene expression profiling of ameloblastoma and human tooth germ by means of a cDNA microarray. J Dent Res. 2002 Aug;81(8):525-30. doi: 10.1177/154405910208100805[↩]

- Kondo, S., Ota, A., Ono, T., Karnan, S., Wahiduzzaman, M., Hyodo, T., Lutfur Rahman, M., Ito, K., Furuhashi, A., Hayashi, T., Konishi, H., Tsuzuki, S., Hosokawa, Y., & Kazaoka, Y. (2020). Discovery of novel molecular characteristics and cellular biological properties in ameloblastoma. Cancer medicine, 9(8), 2904–2917. https://doi.org/10.1002/cam4.2931[↩]

- Nakamura N, Mitsuyasu T, Higuchi Y, Sandra F, Ohishi M. Growth characteristics of ameloblastoma involving the inferior alveolar nerve: a clinical and histopathologic study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2001 May;91(5):557-62. doi: 10.1067/moe.2001.113110[↩]

- Peter AR, Philipsen HA. 1st ed. London: Quintessence; 2004. Odontogenic Tumors and Allied Lesions; pp. 43–58.[↩][↩][↩]

- Jeddy N, Jeyapradha T, Ananthalakshmi R, Jeeva S, Saikrishna P, Lakshmipathy P. The molecular and genetic aspects in the pathogenesis and treatment of ameloblastoma. J Dr NTR Univ Health Sci. 2013;2:157–61.[↩]

- Becelli R, Carboni A, Cerulli G, Perugini M, Iannetti G. Mandibular ameloblastoma: analysis of surgical treatment carried out in 60 patients between 1977 and 1998. J Craniofac Surg. 2002 May;13(3):395-400; discussion 400. doi: 10.1097/00001665-200205000-00006[↩]

- Barnes L, Eveson JW, Reichart P, Sidransky D, editors. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2005. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours: Head and Neck Tumours.[↩][↩][↩]

- Dunfee BL, Sakai O, Pistey R, Gohel A. Radiologic and pathologic characteristics of benign and malignant lesions of the mandible. Radiographics. 2006 Nov-Dec;26(6):1751-68. doi: 10.1148/rg.266055189[↩]

- Rajendran R. Cyst and tumors of odontogenic origin. In: Rajendran R, Sivapathasundharam B, editors. Shafer’s Text Book of Oral Pathology. 7th ed. Noida: Elsevier; 2012. pp. 259–313.[↩][↩][↩]

- Pindborg JJ. In: Pathology of the Dental Hard Tissue. Copen Hagen: Munksgaard; 1970. Odontog enic tumors; pp. 367–428.[↩]

- Chapelle KA, Stoelinga PJ, de Wilde PC, Brouns JJ, Voorsmit RA. Rational approach to diagnosis and treatment of ameloblastomas and odontogenic keratocysts. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004 Oct;42(5):381-90. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2004.04.005[↩]

- Hong J, Yun PY, Chung IH, Myoung H, Suh JD, Seo BM, Lee JH, Choung PH. Long-term follow up on recurrence of 305 ameloblastoma cases. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007 Apr;36(4):283-8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2006.11.003[↩]

- Gardner DG, Corio RL. Plexiform unicystic ameloblastoma. A variant of ameloblastoma with a low-recurrence rate after enucleation. Cancer. 1984 Apr 15;53(8):1730-5. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19840415)53:8<1730::aid-cncr2820530819>3.0.co;2-u[↩]

- Isomura ET, Okura M, Ishimoto S, Yamada C, Ono Y, Kishino M, Kogo M. Case report of extragingival peripheral ameloblastoma in buccal mucosa. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2009 Oct;108(4):577-9. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2009.06.023. Erratum in: Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2010 Feb;109(2):324. Yamada, Tomoaki [corrected to Yamada, Chiaki].[↩]

- Philipsen HP, Reichart PA, Nikai H, Takata T, Kudo Y. Peripheral ameloblastoma: biological profile based on 160 cases from the literature. Oral Oncol. 2001 Jan;37(1):17-27. doi: 10.1016/s1368-8375(00)00064-6[↩][↩]

- Buchner A, Sciubba JJ. Peripheral epithelial odontogenic tumors: a review. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1987 Jun;63(6):688-97. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(87)90372-0[↩]

- Eversole LR, Leider AS, Hansen LS. Ameloblastomas with pronounced desmoplasia. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1984 Nov;42(11):735-40. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(84)90423-3[↩]

- Reichart PA, Philipsen HA. London: Quintessence Publishing Co Ltd; 2004. Desmoplastic Ameloblastoma: Odontogenic Tumors and Allied Lesions; pp. 69–76.[↩]

- Mintz S, Velez I. Desmoplastic variant of ameloblastoma: report of two cases and review of the literature. J Am Dent Assoc. 2002 Aug;133(8):1072-5. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2002.0331[↩]

- Sun, Z. J., Wu, Y. R., Cheng, N., Zwahlen, R. A., & Zhao, Y. F. (2009). Desmoplastic ameloblastoma – A review. Oral oncology, 45(9), 752–759. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oraloncology.2009.01.016[↩][↩]

- Philipsen HP, Reichart PA, Takata T. Desmoplastic ameloblastoma (including “hybrid” lesion of ameloblastoma). Biological profile based on 100 cases from the literature and own files. Oral Oncol. 2001 Jul;37(5):455-60. doi: 10.1016/s1368-8375(00)00111-1[↩]

- Ng KH, Siar CH. Desmoplastic variant of ameloblastoma in Malaysians. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1993 Oct;31(5):299-303. doi: 10.1016/0266-4356(93)90064-4[↩]

- Robinson L, Martinez MG. Unicystic ameloblastoma: a prognostically distinct entity. Cancer. 1977 Nov;40(5):2278-85. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197711)40:5<2278::aid-cncr2820400539>3.0.co;2-l[↩]

- Robert EM, Diane S. Chicago, Ill, USA: Quintessence; 2003. Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology: A Rationale for Diagnosis and Treatment.[↩]

- Eversole LR, Leider AS, Strub D. Radiographic characteristics of cystogenic ameloblastoma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1984 May;57(5):572-7. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(84)90320-7[↩]

- Philipsen HP, Reichart PA. Unicystic ameloblastoma. A review of 193 cases from the literature. Oral Oncol. 1998 Sep;34(5):317-25. doi: 10.1016/s1368-8375(98)00012-8[↩]

- Reija M.G., Izquierdo M., Rueda J.B., Cantera M.G., Hernández A.V. Ameloblastomas maxillaries: a propósito de dos casos clínicos. Acta otorrinolaringol Espanola. 2001;52(3):261–265. http://www.elsevier.es/es-revista-acta-otorrinolaringologica-espanola-102-linkresolver-ameloblastomas-maxilares-a-proposito-dos-S0001651901782064[↩]

- Oliveira L.R., Matos F., Dominguete R., Zorgetto A., Ribeiro A. Ameloblastoma: report of two cases and a brief literature review. Int J Odontostomat. 2011;5(3):293–299.[↩]

- Underhill T., Katz J., Pope T., Jr., Dunlap C. Radiologic findings of diseases involving the maxilla and mandible. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1992;159(2):345–350. https://www.ajronline.org/doi/pdf/10.2214/ajr.159.2.1632353[↩]

- Becelli R., Carboni A., Cerulli G., Perugini M., Iannetti G. Mandibular ameloblastoma: analysis of surgical treatment carried out in 60 patients between 1977 and 1998. J Craniofacial Surg. 2002;13(3):395–400 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12040207[↩]

- Cohen M.A., Hertzanu Y., Mendelsohn D.B. Computed tomography in the diagnosis and treatment of mandibular ameloblastoma: report of cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1985;43(10):796–800. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3862780[↩]

- Atkinson CH, Harwood AR, Cummings BJ. Ameloblastoma of the jaw. A reappraisal of the role of megavoltage irradiation. Cancer. 1984 Feb 15;53(4):869-73. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19840215)53:4<869::aid-cncr2820530409>3.0.co;2-v[↩]

- Sehdev M., Huvos A., Strong E., Gerold F., Willis G. Ameloblastoma of maxilla and mandible. Cancer. 1974;33(2):324–333. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/4812754[↩]

- [↩]

- Amzerin M., Fadoukhair Z., Belbaraka R. Metastatic ameloblastoma responding to combination chemotherapy: case report and review of the literature. J Med Case Rep. 2011;5:491. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3198715/[↩]

- Ciment L.M., Ciment A.J. Malignant ameloblastoma metastatic to the lungs 29 years after primary resection: a case report. CHEST J. 2002;121(4):1359–1361. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11948077[↩]

- Kaye F.J., Ivey A.M., Drane W.E., Mendenhall W.M., Allan R.W. Clinical and radiographic response with combined BRAF-targeted therapy in stage 4 ameloblastoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107(1):378. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25475564[↩]

- Ally M.S., Tang J.Y., Joseph T. The use of vismodegib to shrink keratocystic odontogenic tumors in patients with basal cell nevus syndrome. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150(5):542–545. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4024084/[↩]

- Becelli R., Carboni A., Cerulli G., Perugini M., Iannetti G. Mandibular ameloblastoma: analysis of surgical treatment carried out in 60 patients between 1977 and 1998. J Craniofacial Surg. 2002;13(3):395–400. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12040207[↩]

- Jackson I., Callan P., Forté R.A. An anatomical classification of maxillary ameloblastoma as an aid to surgical treatment. J Cranio-Maxillofac Surg. 1996;24(4):230–236. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8880449[↩]

- Zwahlen R.A., Gratz K.W. Maxillary ameloblastomas: a review of the literature and of a 15-year database. J Cranio-Maxillo-Facial Surg. 2002;30(5):273–279. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12377199[↩]

- Faras, F., Abo-Alhassan, F., Israël, Y., Hersant, B., & Meningaud, J. P. (2017). Multi-recurrent invasive ameloblastoma: A surgical challenge. International journal of surgery case reports, 30, 43–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijscr.2016.11.039[↩]