Spondyloarthropathy

Spondyloarthropathy also called spondyloarthritis or seronegative spondyloarthritis, refers to a group of inflammatory rheumatic diseases that mainly attacks your spine (spondylitis) and pelvic sacroiliac joints (sacroiliitis) and in some people, the joints of their arms and legs (peripheral arthritis) 1, 2, 3, 4, 5. Spondyloarthropathy can also involve your skin, intestines and eyes. The main symptom of spondyloarthropathy in most patients is chronic low back pain (low back pain more than 3 months). This occurs most often in axial spondyloarthritis.

Spondyloarthropathy according the Assessment of SpondyloArthritis International Society (ASAS) proposed a new classification system, can be classified according to the distribution of joint involvement as being predominantly axial (axial spondyloarthritis) or peripheral (peripheral spondyloarthritis) 6, 4:

- Axial spondyloarthropathy: predominantly axial symptoms (i.e. chronic low back pain)

- axial mean it’s related to or situated in the central part of the body, encompassing the full spine and pelvis

- preradiographic or non-radiographic: no changes on radiographs (but may have MRI changes)

- radiographic: sacroiliitis on radiographs

- The most common type of spondyloarthropathy is axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA), a term that covers both ankylosing spondylitis (AS) and nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis (nr-axSpA) where joint damage isn’t visible on X-rays. The names are confusing, but what’s important is that both mainly cause inflammation in joints in the spine and pelvis. Non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis (nr-axSpA) and ankylosing spondylitis are two sub-types of axial spondyloarthritis. They can be thought of as two ends of the spectrum of axial spondyloarthritis. The difference is that in non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis (nr-axSpA), the sacroiliac (SI) joints do not show definitive damage on x-rays, as seen in ankylosing spondylitis. Many people with nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis (nr-axSpA) never go on to develop ankylosing spondylitis, and some patients with ankylosing spondylitis have only mild symptoms. There are many gradations in between that vary considerably from person to person.

- Peripheral spondyloarthropathy: only peripheral manifestations characterized by inflammatory pain and arthritis in peripheral joints and tendons other than the spine (e.g. peripheral arthritis, enthesitis, dactylitis)

Spondyloarthropathy consists of the following inflammatory rheumatic diseases 1, 2, 3, 4, 5:

- Ankylosing spondylitis. Ankylosing spondylitis is a kind of arthritis that affects the joints and ligaments of your spine. ‘Ankylosing’ means stiff and ‘spondylo’ means vertebra. About 50% to 92%% of patients with ankylosing spondylitis will be HLA-B27 (human leukocyte antigen-B27) positive 7, 8

- Psoriatic arthritis. Psoriatic arthritis is a chronic, autoimmune form of arthritis that causes joint inflammation (arthritis) and occurs with the skin condition psoriasis. Up 70% of people with psoriatic arthritis have both peripheral and spinal inflammation, but people with a type known as axial psoriatic arthritis only have arthritis in their spine.

- Reactive arthritis. Reactive arthritis is mainly triggered by an intestinal, urinary or genital tract infection, which is often treated with antibiotics. Reactive arthritis usually goes away on its own.

- Enteropathic arthritis is arthritis associated with inflammatory bowel disease like ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. Like ankylosing spondylitis, enteropathic arthropathy often affects the spine but rarely causes joint destruction or disability.

- Undifferentiated spondyloarthropathy also known as undifferentiated arthritis, is defined as any arthritis of recent onset that cannot be classified according to the existing criteria for specific rheumatic disorders that lacks the clinical, serological and radiological features that would allow specific diagnosis 9. Undifferentiated spondyloarthropathy often turns out to be an early presentation of a more well-known form of arthritis with 40 to 50% of undifferentiated spondyloarthropathy patients remit spontaneously, while 30% develop rheumatoid arthritis (RA) 10, 11.

Many patients with spondyloarthritis have a first degree relative (e.g., father, mother, brother or sister) with spondyloarthritis or spondyloarthritis-related disease such as ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, psoriasis, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis and uveitis. All forms of spondyloarthritis may ultimately develop into ankylosing spondylitis in patients with longstanding disease 12.

Many patients with spondyloarthropathy have the axial skeleton involvement and are typically negative to rheumatoid factor (RF). However, a small proportion of patients may have serum rheumatoid factor (RF) detected. Most spondyloarthropathy patients test positive for the protein product of the HLA-B27 gene.

To diagnosed spondyloarthropathy, your doctor typically will begin by going through your medical history and conducting a thorough physical exam. Tests and procedures that may be used for diagnosing spondyloarthritis include:

- Blood tests, to determine your HLA-B27 status and measure markers of inflammation (C-reactive protein [CRP], erythrocyte sedimentation rate [ESR]).

- Having the HLA-B27 gene doesn’t mean you’ll develop any of the conditions in the spondyloarthropathy family 13, 14, 15. The HLA-B27 gene alone doesn’t cause seronegative spondyloarthropathy and about 98% of people who carry it never have back pain. On the flip side, people of African descent are much less likely than others to carry HLA-B27 but can still develop inflammatory spondyloarthropathy 16.

- Imaging studies, to look for evidence of inflammation and rule out other potential causes of the patient’s symptoms. The specific type of imaging study (X-ray, ultrasound, MRI) will vary depending on the your symptoms. However, Imaging does not play a major role in differentiating between the spondyloarthropathy subtypes as imaging features are similar, especially in early disease. Exceptions to this rule are 17:

- undifferentiated spondyloarthropathy: no definite radiologic signs of sacroiliitis

- psoriatic arthritis: associated with parasyndesmophytes, a form of bony outgrowth distinct from syndesmophytes

- Also, spondylitis with bone marrow edema of the entire vertebra occurs more frequently in psoriatic arthritis.

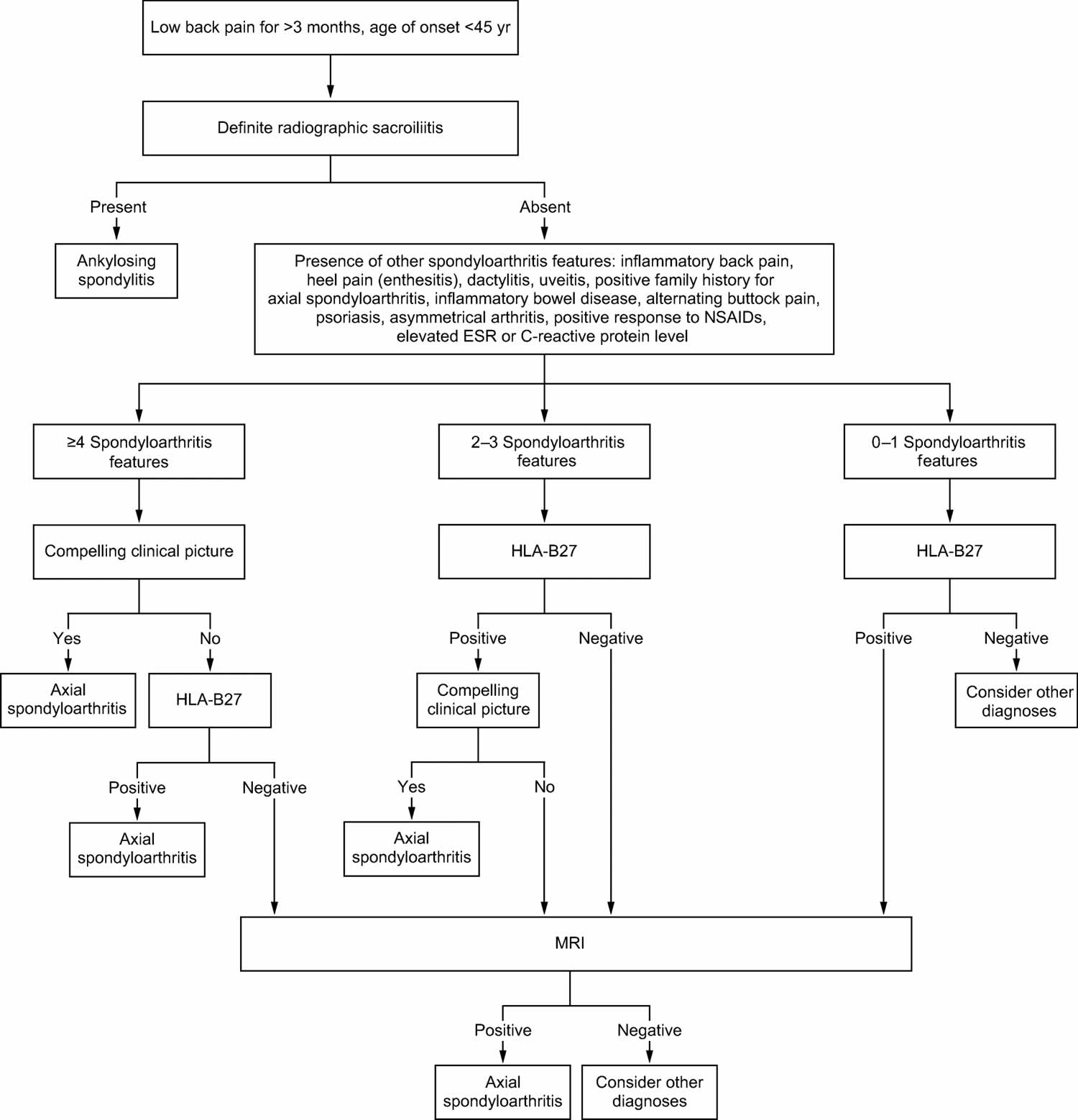

It is important to note that as there are no specific diagnostic tests for most spondyloarthropathies (see Figure 1). For this reason, it is essential to correlate the findings in history and physical examination with laboratory, radiological, and sometimes histopathological findings to establish the diagnosis.

The goal of treatment for spondyloarthropathies is to improve function, decrease pain, and reduce the risk of complications. Management should include lifestyle interventions, including an exercise program to maintain posture, strength, and range of movement. Patients should also be monitored for osteoporosis and encouraged to cease smoking.

Exercise is important for everyone with arthritis, but it’s a fundamental part of treatment if you have ankylosing spondylitis or nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis (nr-axSpA). Exercise relieves pain better than medications and is the only way to keep your spine healthy and mobile. The American College of Rheumatology recommends that everyone with axial spondyloarthropathy get physical therapy and regularly perform exercises that “promote spine extension and mobility.” Swimming, in particular, is terrific for back health.

The first-line treatment for spine pain is nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) like naproxen, ibuprofen and celecoxib. For many people with ankylosing spondylitis or nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis (nr-axSpA), these drugs along with exercise are enough to control symptoms. They are quite effective, reducing pain, tenderness, and stiffness in 80% of patients.

If you don’t get relief from NSAIDs or have severe peripheral arthritis, you and your doctor might consider a tumor necrosis factor (TNF) blocker (anti-TNF-alpha therapy) like infliximab (Remicade), etanercept, adalimumab (Humira) or certolizumab (Cimzia). Certolizumab is the only anti-TNF-alpha therapy (TNF inhibitor) approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis (nr-axSpA), but doctors prescribe the others off-label based on research and clinical experience. These drugs can reduce the spinal and peripheral joint inflammation of ankylosing spondylitis and control extra-articular symptoms. Another option is an interleukin (IL)-17 blocker like secukinumab (Cosentyx) or ixekizumab (Taltz), both FDA-approved for nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis (nr-axSpA). All of these medications, called biologics, are expensive and can have potentially serious side effects, so be sure you and your doctor weigh the pros and cons carefully.

Other medications for severe peripheral arthritis that you and your doctor might consider are called disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs), which include sulfasalazine and methotrexate. Intra-articular corticosteroid injections have a modest benefit for peripheral arthritis 18.

The treatment for psoriatic arthritis targets the joints and skin lesions. Anti-TNF-alpha therapy (TNF inhibitor) for psoriatic arthritis has been a significant advance, resulting in a significant improvement in symptoms and a delay in progression of the disease. Secukinumab, an anti-interleukin-17A monoclonal antibody, is effective at treating psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis.

The management of reactive arthritis involves assessing and treating an active infection. Chlamydia infections should be treated with antibiotics. There is no evidence to support the use of antibiotics for treatment of urogenital or enteric forms of reactive arthritis. High-dose NSAIDs are also used to treat patients with reactive arthritis. Indomethacin 50–75 mg twice daily is commonly used. Persistent reactive arthritis may respond to disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) such as sulfasalazine, azathioprine, or methotrexate 18.

Enteropathic arthritis is also treated with NSAIDs and cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors, but these can cause flare-ups of inflammatory bowel disease. DMARDs are beneficial for gastrointestinal and joint involvement. Anti-TNF agents can be used if traditional DMARDs fail; however, there have been rare cases of inflammatory bowel diseases precipitated by etanercept. Total colectomy (removal of the affected colon) does not improve axial involvement in inflammatory bowel disease 19.

Surgical treatment is helpful in some patients. Total hip replacement is very useful for those with hip pain and disability due to joint destruction from cartilage loss. Spinal surgery is rarely necessary, except for those with traumatic fractures (broken bones due to injury) or to correct excess flexion deformities of the neck, where the patient cannot straighten the neck.

Figure 1. Spondyloarthropathy diagnostic algorithm

Abbreviations: axSpA = axial spondyloarthritis; ESR = erythrocyte sedimentation rate; HLA-B27 = human leukocyte antigen-B27; MRI = magnetic resonance imaging

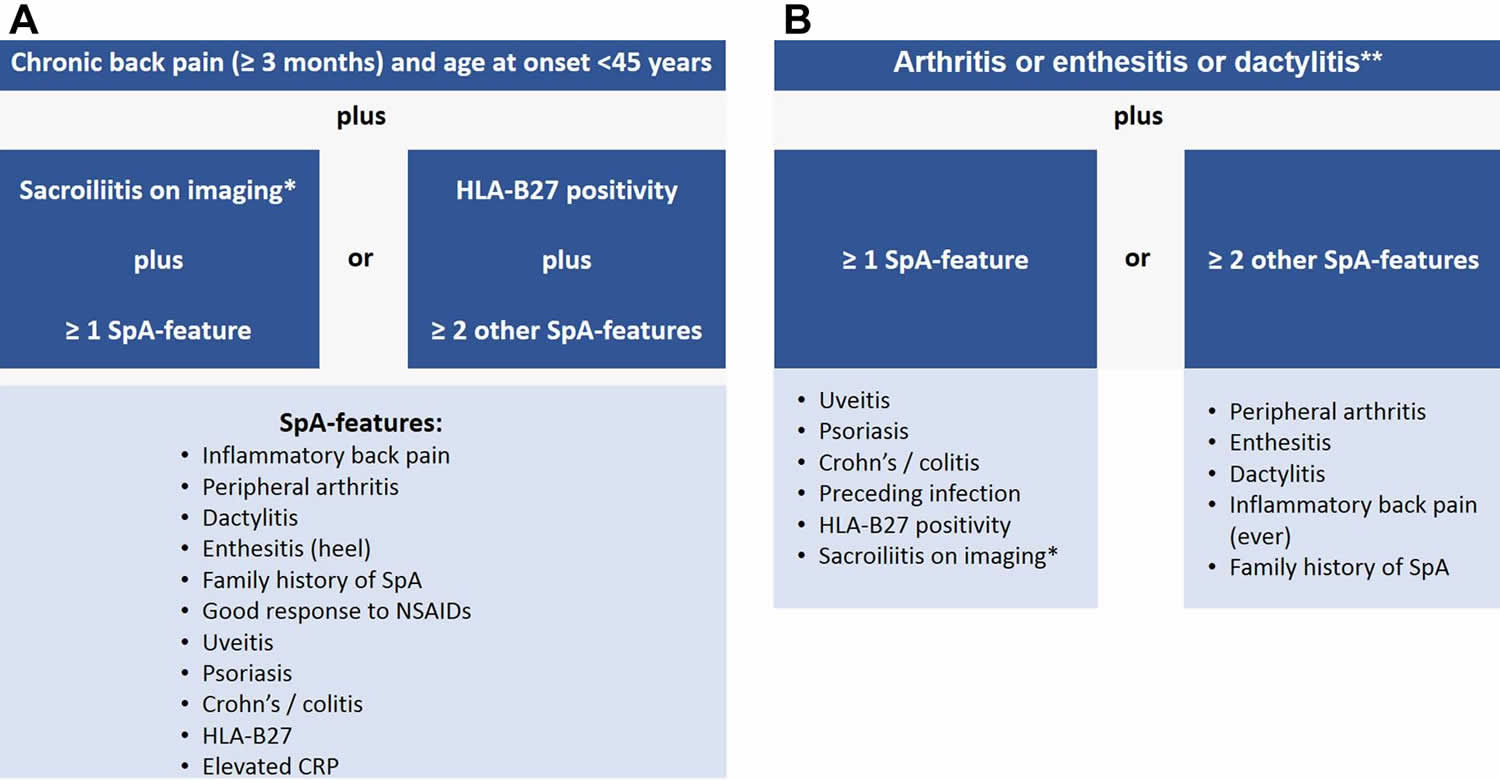

[Source 20 ]Figure 2. Spondyloarthropathy diagnostic criteria (Assessment of SpondyloArthritis International Society (ASAS) criteria)

Footnotes: Assessment of SpondyloArthritis International Society (ASAS) criteria for axial and peripheral spondyloarthritis. (A) ASAS classification criteria for axial spondyloarthritis; (B) ASAS classification criteria for peripheral spondyloarthritis. *Sacroiliitis on imaging refers to definite radiographic sacroiliitis according to the modified New York criteria or active sacroiliitis on MRI according to the ASAS definition. **Peripheral arthritis: usually predominantly lower limbs and/or asymmetric arthritis; enthesitis: clinically assessed; dactylitis: clinically assessed. SpA = spondyloarthritis.

[Source 21 ]Who gets spondyloarthropathy?

Many spondyloarthropathy, especially ankylosing spondylitis and nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis (nr-axSpA), strike young adults, often when they’re still in school or just starting careers and families 16. Ankylosing spondylitis tends to start in the teens and 20s and affects males two to three times more often than females although it is likely that females are underdiagnosed. Family members of affected people are at higher risk, depending partly on whether they inherited the HLA-B27 gene.

There is an uneven ethnic distribution of ankylosing spondylitis. The highest frequency appears in the far north in cultures such as Alaskan and Siberian Eskimos and Scandinavian Lapps (also called Samis), who have a higher frequency of HLA-B27. It also occurs more often in certain Native American tribes in the western U.S. and Canada. African Americans are affected less often than other races.

Based on data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), the frequency of ankylosing spondylitis in the U.S., is 0.5 percent. The frequency for axial spondyloarthritis is 1.4 percent.

Although it was long believed that men with ankylosing spondylitis outnumbered women by three to one, it’s now known that women are underdiagnosed, especially when bone damage doesn’t show up on X-rays. Newer research suggests seronegative spondyloarthropathy is an equal opportunity offender, striking men and women equally. Black Americans are less likely to have ankylosing spondylitis than whites but tend to have more severe disease 16.

Spondyloarthropathy types

Spondyloarthropathy according the Assessment of SpondyloArthritis International Society (ASAS) proposed a new classification system, can be classified according to the distribution of joint involvement as being predominantly axial (axial spondyloarthritis) or peripheral (peripheral spondyloarthritis) 6, 4:

- Axial spondyloarthropathy: predominantly axial symptoms (i.e. chronic low back pain)

- axial mean it’s related to or situated in the central part of the body, encompassing the full spine and pelvis

- preradiographic or non-radiographic: no changes on radiographs (but may have MRI changes)

- radiographic: sacroiliitis on radiographs

- The most common type of spondyloarthropathy is axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA), a term that covers both ankylosing spondylitis (AS) and nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis (nr-axSpA) where joint damage isn’t visible on X-rays. The names are confusing, but what’s important is that both mainly cause inflammation in joints in the spine and pelvis. Non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis (nr-axSpA) and ankylosing spondylitis are two sub-types of axial spondyloarthritis. They can be thought of as two ends of the spectrum of axial spondyloarthritis. The difference is that in non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis (nr-axSpA), the sacroiliac (SI) joints do not show definitive damage on x-rays, as seen in ankylosing spondylitis. Many people with nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis (nr-axSpA) never go on to develop ankylosing spondylitis, and some patients with ankylosing spondylitis have only mild symptoms. There are many gradations in between that vary considerably from person to person.

- Peripheral spondyloarthropathy: only peripheral manifestations characterized by inflammatory pain and arthritis in peripheral joints and tendons other than the spine (e.g. peripheral arthritis, enthesitis, dactylitis)

Spondyloarthropathy consists of the following inflammatory rheumatic diseases 1, 2, 3, 4, 5:

- Ankylosing spondylitis. Ankylosing spondylitis is a kind of arthritis that affects the joints and ligaments of your spine. ‘Ankylosing’ means stiff and ‘spondylo’ means vertebra. About 50% to 92%% of patients with ankylosing spondylitis will be HLA-B27 (human leukocyte antigen-B27) positive 7, 8

- Psoriatic arthritis. Psoriatic arthritis is a chronic, autoimmune form of arthritis that causes joint inflammation (arthritis) and occurs with the skin condition psoriasis. Up 70% of people with psoriatic arthritis have both peripheral and spinal inflammation, but people with a type known as axial psoriatic arthritis only have arthritis in their spine.

- Reactive arthritis. Reactive arthritis is mainly triggered by an intestinal, urinary or genital tract infection, which is often treated with antibiotics. Reactive arthritis usually goes away on its own.

- Enteropathic arthritis is arthritis associated with inflammatory bowel disease like ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. Like ankylosing spondylitis, enteropathic arthropathy often affects the spine but rarely causes joint destruction or disability.

- Undifferentiated spondyloarthropathy also known as undifferentiated arthritis, is defined as any arthritis of recent onset that cannot be classified according to the existing criteria for specific rheumatic disorders that lacks the clinical, serological and radiological features that would allow specific diagnosis 9. Undifferentiated spondyloarthropathy often turns out to be an early presentation of a more well-known form of arthritis with 40 to 50% of undifferentiated spondyloarthropathy patients remit spontaneously, while 30% develop rheumatoid arthritis (RA) 10, 11.

Axial spondyloarthropathy

The most common type of spondyloarthropathy is axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA) also called axial spondyloarthrititis, is a term that covers both ankylosing spondylitis (AS) and nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis (nr-axSpA) where joint damage isn’t visible on X-rays. The names are confusing, but what’s important is that both mainly cause inflammation in joints in the spine and pelvis. Axial spondyloarthropathy predominantly present with axial symptoms such as low back pain (i.e. chronic low back pain) and morning stiffness. Ankylosing spondylitis and nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis (nr-axSpA) are seen as two regions on a spectrum of inflammatory conditions rather than early and late stages of a single disease. Many people with nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis (nr-axSpA) never go on to develop ankylosing spondylitis, and some patients with ankylosing spondylitis have only mild symptoms. There are many gradations in between that vary considerably from person to person. There is a long delay, on average 14 years, between symptoms onset and diagnosis 22.

The prevalence of axial axial spondyloarthropathy is ~1% 22. Age of onset is in the 3rd and 4th decades 21.

Assessment of SpondyloArthritis International Society (ASAS) criteria for the diagnosis of axial spondyloarthropathy 6, 4:

- ≥3 months of back pain and age of onset ≤45 years

- sacroiliitis on imaging and ≥1 clinical feature or HLA-B27 and ≥2 clinical features:

- Clinical features

- Inflammatory back pain: insidious onset; improvement with exercise but not with rest; night pain; morning back stiffness ≥30 minutes; alternating gluteal pain 2

- arthritis

- heel enthesitis

- uveitis

- dactylitis

- psoriasis

- Crohn disease

- good response to NSAIDs (absent pain) 24-48 hours after a full dose 21

- family history of axial spondyloarthropathy

- elevated CRP

- Clinical features

Imaging forms an important part of the work-up as the clinical features are somewhat non-specific 21. Radiographic evidence of axial spondyloarthropathy will be present in ~50% of patients at initial diagnosis. Some will progress to having radiographic evidence whilst others will never have radiographic evidence of axial spondyloarthropathy 22.

Plain radiograph

- Sacroiliac joint x-rays are the first-line modality. Definite radiographic sacroiliitis is characterized by the New York Criteria as bilateral grade 2 or unilateral grade 3 21.

MRI

Sacroiliac joint MRI is the second line modality. The Assessment in SpondyloArthritis International Society (ASAS) classification criteria first published in 2009 23 with a revised consensus definition of a positive MRI (active sacroiliitis) in 2016 24, utilizes imaging features of the sacroiliac joints on x-ray and MRI as one of many criteria for the classification of axial spondyloarthritis with the aim to create homogeneous populations for research 25. Its use in clinical practice has been discouraged by some authors 26. The sensitivity and specificity of the ASAS classification criteria are around 80% 26, 27, which limits its use as a diagnostic tool 26.

- The phrase “active sacroiliitis on MRI” can be used if there are features highly suggestive of inflammation. These features can be broken down into two categories 24:

- Required MRI features

- bone marrow edema (BMO) / osteitis on a T2-weighted sequence sensitive for free water (such as short tau inversion recovery (STIR) or T2FS) or bone marrow contrast enhancement on a T1-weighted sequence (such as T1FS post-Gd)*

- inflammation must be clearly present and located in a typical anatomical area (subchondral bone)

- MRI appearance must be highly suggestive of a spondyloarthropathy

- Not required MRI features – other findings related to sacroiliitis may be observed on MRI but are not required to fulfill the imaging criterion of “active sacroiliitis on MRI”:

- the sole presence of other inflammatory lesions such as synovitis, enthesitis or capsulitis without concomitant BMO is not sufficient for the definition of “active sacroiliitis on MRI”

- in the absence of MRI signs of BMO, the presence of structural lesions such as fat metaplasia, sclerosis, erosion or ankylosis does not meet the definition of “active sacroiliitis on MRI”, but can be considered chronic lesions

- Required MRI features

- *the ASAS 2016 consensus definition removed the quantitative requirement (i.e. two slices or two locations) from the required MRI features 24, 26

Ankylosing spondylitis

Ankylosing spondylitis is a type of seronegative spondyloarthropathy that causes arthritis of your spine and sacroiliac (SI) joints, although other large and small joints in your body can also become involved (e.g., shoulders, hips, ribs, heels, and small joints of the hands and feet) 28. Ankylosing spondylitis causes inflammation between your vertebrae, which are the bones that make up your spine, and in the joints between your spine and pelvis. In some people, it can affect other joints. Sometimes the eyes can become involved (known as iritis or uveitis), and — rarely — the lungs and heart can be affected. In more advanced ankylosing spondylitis cases this inflammation can lead to ankylosis (fusion) — new bone formation in the spine — causing sections of the spine to fuse in a fixed, immobile position.

Ankylosing spondylitis is more common and more severe in men. It often runs in families. The cause is unknown, but it is likely that both genes and factors in the environment playing a role.

The most common early symptoms of ankylosing spondylitis are frequent back pain and stiffness in your lower back and buttocks, which comes on gradually over the course of a few weeks or months. At first, discomfort may only be felt on one side, or alternate sides. The pain is usually dull and diffuse, rather than localized.

This pain and stiffness is usually worse in the mornings and during the night, but may be improved by a warm shower or light exercise. Also, in the early stages of ankylosing spondylitis, there may be mild fever, loss of appetite, and general discomfort. It is important to note that back pain from ankylosing spondylitis is inflammatory in nature and not mechanical.

The pain typically becomes persistent (chronic) and is felt on both sides, usually lasting for at least three months. Over the course of months or years, the stiffness and pain can spread up the spine and into the neck. Pain and tenderness spreading to the ribs, shoulder blades, hips, thighs, and heels is possible as well. Some people have symptoms that come and go. Others have severe, ongoing pain.

Ankylosing spondylitis has no cure, but medicines can relieve symptoms and may keep the disease from getting worse. Eating a healthy diet, not smoking, and exercising can also help. In rare cases, you may need surgery to straighten the spine.

Ankylosing spondylitis symptoms

The most common early symptoms of ankylosing spondylitis are frequent back pain and stiffness in your lower back and buttocks, which comes on gradually over the course of a few weeks or months. At first, discomfort may only be felt on one side, or alternate sides. The pain is usually dull and diffuse, rather than localized.

This pain and stiffness is usually worse in the mornings and during the night, but may be improved by a warm shower or light exercise. Also, in the early stages of ankylosing spondylitis, there may be mild fever, loss of appetite, and general discomfort. It is important to note that back pain from ankylosing spondylitis is inflammatory in nature and not mechanical.

The pain typically becomes persistent (chronic) and is felt on both sides, usually lasting for at least three months. Over the course of months or years, the stiffness and pain can spread up the spine and into the neck. Pain and tenderness spreading to the ribs, shoulder blades, hips, thighs, and heels is possible as well. Some people have symptoms that come and go. Others have severe, ongoing pain.

It is important to note that the course of ankylosing spondylitis varies greatly from person to person. So too can the onset of symptoms. Although symptoms usually start to appear in late adolescence or early adulthood (ages 17 to 45), symptoms can occur in children or much later in life.

Over time, ankylosing spondylitis can fuse your vertebrae together, limiting movement.

In a minority of individuals, pain does not start in the lower back, or even the neck, but in a peripheral joint such as the hip, ankle, elbow, knee, heel, or shoulder. This pain is commonly caused by enthesitis, inflammation of the site where a ligament or tendon attaches to bone. Inflammation and pain in peripheral joints is more common in children with ankylosing spondylitis. This can be confusing since, without the immediate presence of back pain, ankylosing spondylitis may look like some other form of arthritis.

Varying levels of fatigue may also result from the inflammation caused by ankylosing spondylitis as the body must expend energy to deal with the inflammation, thus causing fatigue. Also, mild to moderate anemia, which may also result from the inflammation, can contribute to an overall feeling of tiredness.

Many people with ankylosing spondylitis also experience bowel inflammation, which may be associated with Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis.

Ankylosing spondylitis is often accompanied by iritis or uveitis (inflammation of the eyes). About one-third of people with ankylosing spondylitis will experience inflammation of the eye at least once. Signs of iritis or uveitis are: Eye(s) becoming painful, watery, and red, blurred vision, and sensitivity to bright light.

Ankylosing spondylitis diagnosis

A rheumatologist is commonly the type of physician who will diagnose ankylosing spondylitis, since they are doctors who are specially trained in diagnosing and treating disorders that affect the joints, muscles, tendons, ligaments, connective tissue, and bones. A thorough physical exam, including X-rays, individual medical history, and a family history of ankylosing spondylitis, as well as blood work (including a test for HLA-B27) are factors in making a diagnosis.

Bamboo spine is a pathognomonic radiographic feature seen in ankylosing spondylitis that occurs as a result of vertebral body fusion by marginal syndesmophytes 29. Bamboo spine is often accompanied by fusion of the posterior vertebral elements as well. A bamboo spine typically involves the thoracolumbar and/or lumbosacral junctions and predisposes to unstable vertebral fractures and Andersson lesions (inflammatory involvement of the intervertebral discs by spondyloarthritis) 29, 30.

In a bamboo spine, the outer fibers of the annulus fibrosus of the intervertebral discs ossify, which results in the formation of marginal syndesmophytes between adjoining vertebral bodies 31. The resulting radiographic appearance, therefore, is that of thin, curved, radiopaque spicules that completely bridge adjoining vertebral bodies. There is also accompanying squaring of the anterior vertebral body margins with associated reactive sclerosis of the vertebral body margins (shiny corner sign) 31. Together these give the impression of undulating continuous lateral spinal borders on AP spinal radiographs and resemble a bamboo stem; hence the term bamboo spine.

The hallmark of ankylosing spondylitis is involvement of the sacroiliac (SI) joints. Some physicians still rely on X-ray to show erosion typical of sacroiliitis, which is inflammation of the sacroiliac joints. Using conventional X-rays to detect this involvement can be problematic because it can take seven to 10 years of disease progression for the changes in the sacroiliac (SI) joints to be serious enough to show up on conventional X-rays.

Another option is to use MRI to check for sacroiliac (SI) involvement, but MRI can be cost prohibitive in some cases.

A diagnosis of ankylosing spondylitis is based on your medical history and a physical examination. You may also have imaging or blood tests.

Ankylosing spondylitis treatment

At the present time there is no cure for ankylosing spondylitis; however, your doctor will work with you to relieve your symptoms, maintain proper posture and slow the progression of the disease. In most cases, treatment includes medication and physical therapy. Sometimes, people with severe disease need surgery to repair joint damage.

Medications

Most people with ankylosing spondylitis take medications, which may include one or more of the following:

- Over-the-counter anti-inflammatory medications to relieve pain and inflammation are commonly used to treat ankylosing spondylitis.

- Biologic medications target specific immune messages and interrupt the signal, helping to decrease or stop inflammation. These medications may be prescribed if your disease is unresponsive to other treatments.

- Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors may also be prescribed if your disease is unresponsive to other treatments. These medications send messages to specific cells to stop inflammation from inside the cell.

- Corticosteroids can help decrease inflammation and provide some pain relief. They are usually injected into the joint. Because they are potent drugs, your doctor will determine how much and how many injections you should receive to achieve the desired benefit.

Physical therapy

Your doctor may recommend physical therapy to help:

- Relieve pain.

- Strengthen back and neck muscles.

- Improve core and abdominal muscle strength because these muscles provide support for your back.

- Improve posture.

- Maintain and improve flexibility in joints.

A physical therapist can recommend the best sleeping positions and an exercise program. Because your symptoms may worsen when inactive or at rest, it’s important to stay active and exercise regularly.

Surgery

If you have severe joint damage and you are unable to participate in your daily activities, your doctor may recommend surgery. Surgery is not for everyone. You and your doctor can discuss the options and choose what is right for you.

Your doctor will consider the following before recommending surgery:

- Your overall health.

- The condition of the affected bone or joint.

- The risks and benefits of the surgery.

Types of surgery may include joint repairs and joint replacements.

Rarely, some people may have surgery to correct or straighten the spine or repair fractures (breaks) in the vertebrae.

Non-Radiographic Axial Spondyloarthritis

Non-Radiographic Axial Spondyloarthritis (nr-axSpA) is a form of arthritis in the family of spondyloarthritis diseases. Non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis (nr-axSpA) primarily affects your spine, but other parts of your body are also often involved. It causes inflammation in the spine and elsewhere that can lead to various symptoms including pain and stiffness.

Here is a breakdown of the terms associated with non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis 32:

- Axial – Relating to or situated in the central part of the body, encompassing the full spine and pelvis.

- Spondyloarthritis – Inflammatory arthritis involving the spine and peripheral joints.

- Non-Radiographic – No definitive damage seen on x-rays of spine, specifically in the sacroiliac (SI) joints.

Non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis (nr-axSpA) is most closely associated with a highly similar condition, radiographic axial spondyloarthritis (r-axSpA), which is more commonly called ankylosing spondylitis.

Non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis (nr-axSpA) and ankylosing spondylitis (AS) are two sub-types of axial spondyloarthritis. They can be thought of as two ends of the spectrum of axial spondyloarthritis. The difference is that in non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis (nr-axSpA), the sacroiliac (SI) joints do not show definitive damage on x-rays, as seen in ankylosing spondylitis.

A rheumatologist will generally diagnose and treat non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis (nr-axSpA). Unfortunately, there is no clear diagnostic test for non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis (nr-axSpA). This means that a thorough physical exam by a knowledgeable doctor, along with a detailed patient and family history, is key to help with the diagnosis. Blood tests and imaging (x-ray or MRI) are also often helpful.

Non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis symptoms

The first symptoms of non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis (nr-axSpA) are often described as persistent pain and stiffness in the lower back and buttocks, which come on gradually over the course of a few weeks or months. This pain and stiffness are usually worse in the mornings and during the night, but may improve after a warm shower or light exercise. At first, discomfort may only be felt on one side, or alternate sides. The pain is usually dull and diffuse, rather than localized. Sometimes, these symptoms can be severe.

Although symptoms usually start to appear in late adolescence or early adulthood (ages 17 to 45), symptoms can occur in children or much later in life. The course of non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis (nr-axSpA) varies greatly from person to person — no two individuals may have the exact same symptoms.

The back pain people with non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis (nr-axSpA) experience is usually inflammatory back pain. Key characteristics of inflammatory back pain include pain and stiffness that 33:

- Start before age 45

- Develop and worsen gradually

- Persist for more than three months

- Ease with physical activity and exercise

- Get worse with immobility (especially overnight and early morning)

- Pain and stiffness in other areas of the body, such as the neck, shoulders, the ribs, hips, knees, and heels, are also common. In some individuals, pain does not start in the lower back, or even the neck, but in one of the peripheral joints mentioned above. This can be confusing since, without the immediate presence of back pain, non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis (nr-axSpA) may look like other forms of arthritis. A person’s sex can affect the location of initial pain in non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis (nr-axSpA). For some women, the neck and peripheral joints are often affected first, whereas in men it is more likely to be the lower back.

Other main symptoms of non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis (nr-axSpA) may Include:

- Iritis / Uveitis – Inflammation of the eye. Symptoms often occur in one eye at a time, and may include redness, pain, sensitivity to light, and skewed vision. (Note: iritis is a medical emergency and needs immediate attention as untreated eye inflammation can lead to permanent damage and even blindness.)

- Enthesitis– Inflammation of the entheses, which is where ligaments or tendons attach to the bone. Symptoms include swelling and tenderness. Common areas impacted include the Achilles tendon at the back of the heel, the plantar fascia at the base of the heel, the rib cage, and the spine.

- Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) – Gastrointestinal issues and bowel inflammation, which may be associated with Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis.

- Psoriasis – A scaly skin rash.

Fatigue is a common complaint in non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis (nr-axSpA), and one that doesn’t often receive the attention it deserves. Fatigue can negatively impact one’s work, family or social life, ability to focus, and even emotional state.

Uncontrolled inflammation is the factor most closely associated with fatigue in non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis (nr-axSpA). If inflammation is extensive, then the body must use energy to deal with it, producing feelings of profound, chronic tiredness. The release of certain cell messengers (cytokines) during the inflammatory process also can produce the sensation of fatigue, as well as mild to moderate anemia in some cases, which itself can further exacerbate fatigue. When inflammation is well controlled and the disease is properly managed, fatigue often lessens and energy returns.

Uncontrolled pain and stiffness can make it difficult to sleep. Besides causing fatigue, sleep deprivation can increase pain, creating a feedback loop of pain causing sleeplessness, which then causes more pain, and so on.

For all these reasons, effective pain management is crucial. Though many people with non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis (nr-axSpA) respond well to medications alongside exercise and physical therapy, others experience more severe pain even with appropriate treatment. In these cases, it is important to work with your medical team to find appropriate solutions and design a comprehensive plan to treat the pain. Speaking with your rheumatologist about pain and fatigue is the first step.

Non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis diagnosis

Often a rheumatologist will test the blood for the HLA-B27 gene marker, and for higher-than-normal inflammatory markers such as erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP), which may indicate systemic inflammation. It is important to note that bloodwork is not always helpful, as not everyone with non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis (nr-axSpA) will have the HLA-B27 gene marker, or always show elevated inflammatory markers.

There is no association between non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis (nr-axSpA) and rheumatoid factor (RF) or antinuclear antibodies (associated with lupus).

Imaging tests such as an x-ray or MRI can be powerful tools in discovering inflammation or damage in the spine. However, those with non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis (nr-axSpA) will not have definitive damage to the sacroiliac (SI) joints visible on plain x-rays.

MRI of the sacroiliac (SI) joints can show evidence of inflammation not visible on x-rays. Therefore, MRI can be a very important tool in diagnosing non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis (nr-axSpA).

Non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis treatment

Non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis (nr-axSpA) treatment is similar to treatment for ankylosing spondylitis 34. Treatment goals should focus on relieving pain and stiffness, maintaining axial spine motion and functional ability, and preventing spinal complications. Non-pharmacologic interventions should include regular exercise, postural training, and physical therapy 35. First-line medication therapy is with long-term, daily non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Should NSAIDs not provide adequate relief, they can be combined with or substituted for tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (TNF-Is) such as adalimumab, infliximab, or etanercept. Treatment with secukinumab or ixekizumab is conditionally recommended in patients with non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis (nr-axSpA), because trials in Non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis (nr-axSpA) have not been reported 34. Response to NSAIDs should be assessed four to six weeks after initiation and twelve weeks following initiation of tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (TNF-Is) 7. Systemic glucocorticoids are not recommended, but local steroid injections may be considered. Specialist referrals may be warranted based on the patient’s clinical picture, potential complications, and extra-articular manifestations of the disease. Rheumatologists may assist in a formal diagnosis, management, and monitoring, while dermatologists, ophthalmologists, and gastroenterologists may assist with associated non-musculoskeletal features of ankylosing spondylitis 36, 37.

Enteropathic spondyloarthropathy

Enteropathic spondyloarthropathy also known as enteropathic arthropathy or enteropathic arthritis, is a type of seronegative spondyloarthropathy that is associated with the occurrence of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), the two best-known types of which are ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. About one in five people (20% of inflammatory bowel disease patients) with Crohn’s or ulcerative colitis will develop enteropathic arthritis 38.

The most common areas affected by enteropathic arthritis are the peripheral (limb) joints and, in some cases, the entire spine can become involved, as well. Abdominal pain and, possibly, bloody diarrhea associated with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) are also components of the disease.

A diagnosis of enteropathic arthritis is made through a complete medical examination including a history of symptoms and taking into account family history. Various tests may also be done to determine the presence of an inflammatory bowel disease and inflammatory arthritis.

Currently, there is no known cure for enteropathic arthritis but there are medications and therapies available to manage the symptoms of both the arthritis and bowel components of the disease.

Enteropathic arthritis causes

The precise causes of the enteropathic arthritis is unknown. Inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract may increase permeability, resulting in absorption of antigenic material, including bacterial antigens 39. These arthrogenic antigens may then localize in musculoskeletal tissues (including entheses and synovial membrane), thus eliciting an inflammatory response. Alternatively, an autoimmune response may be induced through molecular mimicry, in which the host’s immune response to these antigens cross reacts with self-antigens in synovial membrane and other target organs.

Of particular interest is the strong association (80%) between reactive arthritis and human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-B27, an HLA class I molecule. A potentially arthrogenic, bacterially derived antigen peptide could fit in the antigen-presenting groove of the B27 molecule, resulting in a CD8+ T-cell response 39. HLA-B27 transgenic rats develop features of enteropathic arthropathy with arthritis and gut inflammation 39.

Sacroiliitis and spondylitis are associated with HLA-B27 (40% and 60%, respectively). HLA-B27 is not associated with peripheral arthritis, with the exception of reactive arthritis.

HLA accounts only for 40% of the genetic risk for spondyloarthropathy; other polymorphisms in non-HLA genes such tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and IL-23, involved in innate immune recognition and cytokine signaling pathways, are linked with spondyloarthropathy, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and psoriasis 40, 41,

Enteropathic arthritis symptoms

The symptoms of enteropathic arthritis can be divided in two groups:

- Symptoms of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)

- Arthritic symptoms in the joints and, possibly, elsewhere in your body.

- Axial arthritis (sacroiliitis and spondylitis) in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) has the following characteristics:

- Insidious onset of low back pain, especially in younger persons

- Morning stiffness

- Exacerbated by prolonged sitting or standing

- Improved by moderate activity

- More common in Crohn disease than in ulcerative colitis 42

- Independent of gastrointestinal symptoms

- Peripheral arthritis in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) demonstrates the following characteristics:

- Nondeforming and nonerosive

- More common in Crohn’s disease with colonic involvement than in ulcerative colitis

- May precede intestinal involvement, but usually concomitant or subsequent to bowel disease, as late as 10 years following the diagnosis

- Type 1 (pauciarticular [< 5 joints]) – Acute, self-limiting attacks, lasting less than 10 weeks; asymmetrical and affecting large joints, such as the knees, hips and shoulders; strong correlation to IBD activity, most frequently with extensive ulcerative colitis or colonic involvement in Crohn’s disease; associated with other extraintestinal manifestations of IBD 43

- Type 2 (polyarticular [>5 joints]) – Chronic, lasting months to years; more likely symmetrical, affecting small joints of the hands; independent of bowel activity 43

- Enthesitis affects the following parts of the body:

- Heel – Insertion of the Achilles tendon and plantar fascia

- Knee – Tibial tuberosity, patella

- Others – Buttocks, foot

- Extra-articular inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) demonstrates the following characteristics:

- Intestinal – Abdominal pain, weight loss, diarrhea, and hematochezia

- Skin – Pyoderma gangrenosum (in ulcerative colitis), erythema nodosum (in Crohn’s disease)

- Oral – Aphthous ulcers (in ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease)

- Ocular – Uveitis, anterior, nongranulomatous

- Systemic low-grade fever, secondary amyloidosis (in Crohn’s disease)

- Axial arthritis (sacroiliitis and spondylitis) in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) has the following characteristics:

Enteropathic spondyloarthropathy complications

Complications of enteropathic arthropathy are primarily related to inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and include the following:

- Chronic arthritis – Occasionally extra-articular involvement (uveitis)

- Secondary amyloidosis – Mainly with Crohn disease

- Toxicity of therapy

Enteropathic spondyloarthropathy diagnosis

A diagnosis of enteropathic arthritis is made through a complete medical examination including a history of symptoms and taking into account family history. Various tests may also be done to determine the presence of an inflammatory bowel disease and inflammatory arthritis.

Enteropathic spondyloarthropathy treatment

Treatment of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), including surgery, should always be the initial strategy to induce remission of peripheral arthritis 44.

Although nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are usually recommended as first-line therapy for spondyloarthropathies, in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), these agents may exacerbate gastrointestinal symptoms 45. Selection of more cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2)–selective NSAIDs may reduce the risk of bowel flares 46, 47. Corticosteroids may be used systemically or by local injection.

Sulfasalazine (2-3g/day) has been shown to be effective for treatment of the peripheral arthropathy associated with IBD, but not axial disease. [15] While methotrexate can be useful to treat bowel activity in Crohn disease (CD), its effect on joint disease with IBD is less certain.

Although not specifically indicated for an enteropathic arthropathy, the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) antagonists infliximab and adalimumab are indicated to treat ankylosing spondylitis and IBD, and may be effective for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) spondyloarthropathy (including axial involvement) 48, 49, 50, 51, 52.

In a cohort of 30 patients with enteropathic arthropathy affected by active articular and gastrointestinal disease, or axial active articular inflammation, adalimumab led to sustained improvement of both articular and gastrointestinal disease activities. Significant improvement was achieved at the earliest (6-months) assessment and maintained at the 12-months follow-up 53.

Etanercept and golimumab are indicated to treat ankylosing spondylitis 54, but neither has been shown to be helpful with bowel disease, and there have been reports of new-onset inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) with these 2 agents 55.

Vedolizumab is approved for treatment of moderate to severe Crohn disease. A systematic review found evidence that it may be effective in preventing the onset of enteropathic anthropathy but there was no strong evidence for the efficacy of vedolizumab for treating existing arthritis 56.

Enteropathic spondyloarthropathy prognosis

Enteropathic spondyloarthropathy prognosis depends mainly on the prognosis of the underlying inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Severe spinal inflammatory disease may occur, but this is rare.

Psoriatic spondyloarthropathy

Psoriatic spondyloarthropathy also known as psoriatic arthritis, is inflammatory arthritis associated with psoriasis. Psoriasis is a skin disease that causes itchy or sore patches of thick, red skin with silvery scales. You usually get them on your elbows, knees, scalp, back, face, palms and feet, but they can show up on other parts of your body. Psoriatic arthritis is usually negative for rheumatoid factor and hence classified as one of the seronegative spondyloarthropathies. Men and women are equally affected by psoriatic arthritis. The symptoms of psoriatic arthritis come and go but it is a lifelong condition that is usually progressive.

Up to 30 percent of people with psoriasis also develop psoriatic arthritis 57. In most cases (though not always), the psoriasis will precede the arthritis, sometimes by many years. When arthritis symptoms occur with psoriasis, it is called psoriatic arthritis (psoriatic spondyloarthropathy). In these cases, the joints at the end of the fingers are most commonly affected, causing inflammation and pain, but other joints like the wrists, knees, and ankles can also become involved. This is usually accompanied by symptoms in the fingernails and toenails, ranging from small pits in the nails to nearly complete destruction and crumbling as seen in reactive arthritis or fungal infections.

Patients with psoriasis who are more likely to subsequently get arthritis include those with the following characteristics 58:

- Psoriatic nail disease

- Flexural psoriasis, scalp psoriasis or post-auricular psoriasis

- Obesity

- Smoker

- Elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) at baseline.

About 20 percent of patients with psoriatic arthritis will develop spinal involvement, which is called psoriatic spondylitis 59. Inflammation of the spine can lead to complete fusion, as in ankylosing spondylitis or affect only certain areas such as the lower back or neck. Patients who are HLA-B27 positive are more likely than others to have their disease progress to the spine 59.

Psoriatic arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis are considered genetically and clinically related because both are inflammatory rheumatic diseases linked to the HLA-B27 gene 59. HLA-B27 is a powerful predisposing gene associated with several rheumatic diseases. The HLA-B27 gene itself does not cause disease, but can make people more susceptible. While a number of genes are linked to psoriatic arthritis, the highest predictive value is noted with HLA-B27.

Who gets psoriatic arthritis?

Psoriatic arthritis has an incidence of approximately 6 per 100,000 per year and a prevalence of about 1–2 per 1000 in the general population 58. Estimates of the prevalence of psoriatic arthritis among patients with psoriasis range between 4 and 30 per cent. In most patients, arthritis appears 10 years after the first signs of skin psoriasis 58. The first signs of psoriatic arthritis usually occur between the ages of 30 and 50 years of age 58. In approximately 13–17% of cases, arthritis precedes the skin disease 58.

Psoriatic arthritis causes

The exact cause of psoriatic arthritis is not known, but the main contributing factors to the development of psoriatic arthritis are a genetic predisposition, immune factors and the environment 58. In approximately 13–17% of cases, arthritis precedes the skin disease 58. Up to 40 percent of people with psoriatic arthritis have a close relative with the disease 59. If an identical twin has psoriatic arthritis, there is a 75 percent chance that the other twin will have it as well 59.

Genetic factors

As in psoriasis of the skin, many patients with psoriatic arthritis may have a familial tendency toward the condition. A twin study found that arthritis was as common in dizygotic (fraternal) twins as in monozygotic (identical) twins so unknown environmental factors may also be important. First-degree relatives of patients with psoriatic arthritis have a 50-fold increased risk of developing psoriatic arthritis compared with the general population. It is unclear whether this is due to a genetic basis of psoriasis alone, or whether there is a special genetic predisposition to arthritis as well.

Immune factors

Psoriatic arthritis occurs as a result of abnormal interaction between the immune system and the joints. People with psoriatic arthritis seem to have an overactive immune system as evidenced by raised inflammatory markers, increased antibodies and T-lymphocytes.

Activated T cells (in particular CD8+ T cells) have generally been found in the skin and joints of patients with psoriatic arthritis. Several studies have demonstrated that pro-inflammatory cytokines secreted from activated T cells (especially tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), IL-17, IL-18 and IL-23) induce proliferation and activation of synovial and epidermal fibroblasts. CD8+, IL-17+ cells, natural killer (NK) cells and innate lymphoid (ILC3) cells are present in high concentrations in the synovial fluid and skin lesions in patients with psoriatic arthritis.

Environmental factors

Environmental factors implicated in the pathogenesis of psoriatic arthritis include infections (bacterial infections such as streptococci and Borrelia burgdorferi, the cause of Lyme disease; and viral infections such as rubella), trauma (Koebner phenomenon), moving to a new house, recurrent oral ulcers, obesity and bone fractures.

An inverse association with smoking has also been reported in HLA-C*06 allele negative patients 58.

Psoriatic arthritis symptoms

The symptoms of psoriatic arthritis, which vary from person to person, can change in severity. Skin symptoms typically (but not always) appear before the joints become involved, sometimes up to 10 years before. Without treatment, many of these symptoms can lead to progressive, permanent joint damage 59.

While psoriatic arthritis is a single disease, it can have many different symptoms that affect the skin and joints, including:

- Swelling of an entire finger or toe, sometime causing a “sausage” like appearance;

- General joint pain and stiffness, especially in the morning;

- Joint swelling;

- Back pain and stiffness, primarily in the lower back, neck, and upper back;

- Reduced range of motion;

- Painful, often throbbing joints;

- Psoriatic skin lesions;

- Nail changes, including small indentations, lifting and or discoloration of the fingernails or toenails, which occur in almost all patients;

- Generalized fatigue;

- Inflammatory eye conditions that can cause redness, pain, blurred vision, and sensitivity to light. Thirty percent of PsA patients have conjunctivitis, and seven percent have iritis.

People with psoriatic arthritis usually have some skin signs eventually 58.

Psoriatic arthritis develops after skin psoriasis in approximately 75% of patients 58. Remaining patients have either a simultaneous onset of skin and joint psoriasis (10%), or joint symptoms precede any skin problem (15%). The severity of the skin disease does not predict the severity of the joint disease 58.

Plaque psoriasis is the most common form of skin psoriasis seen with psoriatic arthritis. Joint symptoms may be exacerbated by a flare in skin psoriasis but quite commonly the skin symptoms behave independently of joint symptoms. Most people with psoriatic arthritis have mild psoriasis.

Psoriatic arthritis diagnosis

Diagnosing psoriatic arthritis can be tricky, primarily because it shares similar symptoms with other diseases such as osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, and gout. Because of this, misdiagnosis can often be a problem. Early diagnosis, however, is important because long-term joint damage can be warded off better in the first few months after symptoms arise.

The diagnosis of psoriatic arthritis is based on symptoms, an examination of skin and joints and compatible X-ray findings 58. Psoriatic arthritis may present with tendinitis, enthesitis or dactylitis, rather than swollen joints.

X-ray findings that are characteristic of psoriatic arthritis include:

- Changes affecting the joints at the end of the fingers and toes

- Asymmetrical joint involvement (particularly of the sacroiliac joints)

- Erosions: Destruction of the bone and cartilage adjacent to joint spaces

- “Pencil-in-cup” deformity: results from periarticular erosions and bone resorption giving the appearance of a pencil in a cup.

- Subluxation: slipping of the alignment of the joint

- Ankylosis: fusion of bones together across the joint space

- Wispy and dense bony outgrowths around joints (‘whiskering’ and ‘spurs’, respectively)

- Increased calcium salt deposition around the insertion of ligaments and tendons into the bone and other features of enthesopathy.

- Ivory phalanx: increased radiodensity of an entire phalanx as a result of periosteal and endosteal bone formation.

MRI and ultrasound can also aid diagnosis, by identifying enthesitis, tendinitis and ligamentous inflammation.

There are no diagnostic blood tests for psoriatic arthritis but tests may be done to help confirm the diagnosis and rule out other causes.

- Markers of inflammation, ESR (erythrocyte sedimentation rate) and CRP, may reflect the severity of the inflammation in the joints.

- Rheumatoid factor is usually negative but may be positive in up to 10% of patients with psoriatic arthritis.

- Anti-CCP (anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide) is also usually negative but may be positive in up to 7% of patients with psoriatic arthritis.

- HLA-B27 testing

Classification criteria, such as CASPAR criteria, are mainly used for research purposes. Several screening questionnaires have also been developed, such as Toronto Psoriatic Arthritis Screen (ToPAS2), to help to identify patients with psoriatic arthritis.

Psoriatic arthritis treatment

Some treatments for joint psoriasis are also effective for skin psoriasis, so treatment plans may take both skin and joint disease into account 58.

The principles of psoriatic arthritis treatment include early and aggressive treatment in order to prevent joint deformity and resulting morbidity 58. The choice of treatment depends on disease manifestation (pattern of joint involvement, the severity of joint vs skin involvement, the swelling and stiffness, the extent of pain, non-articular involvement) in addition to factors regarding safety (regarding comorbidities), tolerability and patient preference 58.

Non-pharmacological management strategies are important; these include physical and occupational therapy, exercise, prescription of orthotics, and education regarding the disease and about joint protection, disease management, and the proper use of medications 58. Patients should receive assistance in weight reduction and management of cardiovascular risk factors and other comorbidities.

Those with very mild arthritis may require treatment only when their joints are painful and may stop therapy when they feel better. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs such as ibuprofen (Motrin or Advil) or naproxen (Aleve) are used as initial treatment.

If the arthritis does not respond, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) may be prescribed. These include sulfasalazine (Azulfidine), methotrexate (Rheumatrex, Trexall, Otrexup, Rasuvo), cyclosporine (Neoral, Sandimmune, Gengraf), and leflunomide. Sometimes combinations of these drugs may be used together. Azathioprine (Imuran) may help those with severe forms of psoriatic arthritis.

Other treatments include biologics, typically starting with TNF inhibitors such as adalimumab (Humira), certolizumab pegol (Cimzia), etanercept (Enbrel), golimumab (Simponi), infliximab (Remicade). Other biologics used for psoriatic arthritis include the IL-17 inhibitors secukinumab (Cosentyx) and ixekizumab (Taltz), or other classes as ustekinumab (Stelara) and abatacept (Orencia). Newer oral medications, such as tofacitinib (Xeljanz) have also been shown to be effective.

In general, a stepwise approach to pharmacological treatment is adopted 58:

- Step one

- If arthritis is mild and limited to a few joints and the skin disease is not severe, the skin is treated with topical therapies or phototherapy and the joint disease is managed with pain relief (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, heat and ice) and possibly corticosteroid injections into the joint.

- Step two

- Non-biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) improve symptoms of pain and stiffness, but none have been shown to prevent progressive joint damage and all have the potential for serious side effects. The following medications have a beneficial effect on joint disease and psoriasis:

- Methotrexate

- Ciclosporin

- Leflunomide

- Apremilast.

- Systemic steroids may help arthritis but can often cause a flare of psoriasis on reduction in dose or discontinuation.

- Non-biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) improve symptoms of pain and stiffness, but none have been shown to prevent progressive joint damage and all have the potential for serious side effects. The following medications have a beneficial effect on joint disease and psoriasis:

- Step three

- Biological TNF-alpha inhibitors. Biologic response modifiers licensed for use in psoriatic arthritis are:

- Adalimumab

- Etanercept

- Infliximab

- Golimumab.

- Biological TNF-alpha inhibitors. Biologic response modifiers licensed for use in psoriatic arthritis are:

- Step four

- Other agents that are under investigation or are available include:

- Abatacept: (CTLA4-Ig) a selective T-cell co-stimulation modulator

- Tofacitinib: a Janus kinase (JAK1 and 3) inhibitor

- Secukinumab, brodalumab, ixekizumab: anti-IL-17 therapies

- Ustekinumab: a human monoclonal antibody to the shared p40 subunit of IL-13 and IL-23

- Filgotinib: a JAK1 inhibitor

- Guselkumab: an anti-leukin (IL)-23 monoclonal antibody

- Upadacitinib: JAK inhibitor.

- Other agents that are under investigation or are available include:

- Step five

- In some cases, the joint disease may require orthopedic surgery.

Psoriatic arthritis prognosis

Most people with psoriatic arthritis will have ongoing problems with arthritis throughout the rest of their life. Remissions are uncommon; occurring in less than 20% of patients with less than 10% of patients having a complete remission off all medication with no signs of joint damage on X-rays. People with severe psoriatic arthritis have been reported to have a shorter lifespan than average.

Features associated with a relatively good prognosis are:

- Male sex

- Fewer joints involved

- Good functional status at presentation

- Previous remission in symptoms.

Features associated with a poor prognosis include:

- ESR > 15 mm/hr or raised CRP at presentation

- Failure of previous medication trials

- Absence of nail changes

- Joint damage (clinically or radiographically)

- HLA-B27-, -B39-, or -DQw3-positive status.

Living with psoriatic arthritis

Many people with psoriatic arthritis develop stiff joints and muscle weakness due to lack of use. Proper exercise is especially important to improve your overall health and keep your joints flexible. Walking is an excellent way to get exercise. A walking aid or shoe inserts will help to avoid undue stress on feet, ankles, or knees affected by arthritis. An exercise bike provides another good option, as well as yoga and stretching exercises to help with relaxation.

Aqua therapy can be beneficial as some people with psoriatic arthritis find it easier to move in water. Many people with psoriatic arthritis also benefit from physical and occupational therapy to strengthen muscles, protect joints from further damage, and increase flexibility.

Reactive arthritis

Reactive arthritis also known as Reiter’s syndrome, is a type of arthritis that follows a bacterial infection at a different site, commonly triggered by a bacterial infection in the digestive or urinary tract or the genitals 60. Reactive arthritis may also cause inflammation of your eyes, skin and urinary and genital systems. The knee and ankle joints are frequently affected by reactive arthritis, and many people experience pain in the sacroiliac joints in their lower back as well. Reactive arthritis is a type of seronegative spondyloarthropathy, a group of arthritis conditions that typically involve the sacroiliac joints in the lower back, and entheses (places where tendons or ligaments attach to bones). Foot pain in people with reactive arthritis is usually due to inflammation of entheses.

Reactive arthritis can have any or all of these features:

- Pain and swelling of certain joints, often the knees and/or ankles

- Swelling and pain at the heels

- Extensive swelling of the toes or fingers

- Persistent low back pain, which tends to be worse at night or in the morning

Some patients with reactive arthritis also have eye redness and irritation. Still other signs and symptoms include burning with urination and a rash on the palms or the soles of the feet.

The exact cause of reactive arthritis is unknown. However, it most often follows a bacterial infection, but the joint itself is not infected. Reactive arthritis most often occurs in men between the ages of 20 and 40, although it does sometimes affect women. Reactive arthritis may follow an infection in the urethra after unprotected sex. The most common bacteria that cause such infections is called Chlamydia trachomatis. Reactive arthritis can also follow a bacterial gastrointestinal infection (Campylobacter, Salmonella, Shigella and Yersinia) such as food poisoning. In up to one half of people thought to have reactive arthritis, there may be no infection.

Chlamydia most often transmits by sex. Chlamydia often has no symptoms but can cause a pus-like or watery discharge from the genitals. The bowel bacteria can cause diarrhea. If you develop arthritis within one month of a gastrointestinal or a genital infection – especially with a discharge – see your doctor.

Certain genes may make you more likely to get reactive arthritis. Some patients with reactive arthritis carry a gene called HLA-B27. Patients who test positive for HLA-B27 often have a more sudden and severe onset of symptoms. They also are more likely to have chronic (long-lasting) symptoms. Yet, patients who are HLA-B27 negative (do not have the gene) can still get reactive arthritis after exposure to an organism that causes it.

Reactive arthritis is rare in young children, but it may occur in teenagers. Reactive arthritis may occur in children ages 6 to 14 after Clostridium difficile gastrointestinal infections.

Reactive arthritis diagnosis is largely based on symptoms of the inducing infections and clinical features on physical exam typical of reactive arthritis. If indicated, doctors might order a test for Chlamydia infection or test for the HLA-B27 gene. The test for Chlamydia uses a urine sample or a swab of the genitals.

For most people, signs and symptoms of reactive arthritis come and go, eventually disappearing within a few weeks or up to 12 months. But the signs and symptoms of reactive arthritis may become chronic (long-lasting) in some people. Doctors tailor treatment to each individual’s symptoms, and therapy typically involves a combination of medications and exercise.

Who gets reactive arthritis?

The bacteria that cause reactive arthritis are very common and anyone can get reactive arthritis, and it occurs worldwide. In theory, anyone who becomes infected with bacterial infection in their digestive or urinary tract or the genitals might develop reactive arthritis. Yet very few people with bacterial diarrhea actually go on to have serious reactive arthritis. What remains unclear is the role of Chlamydia infection (a sexually transmitted infection) that has no symptoms. It is possible that some cases of arthritis of unknown cause are due to Chlamydia.

Certain factors can increase your risk of developing reactive arthritis, including:

- Sex. Both men and women can get reactive arthritis, but men are more likely to develop it as a result of a sexually transmitted infection. Men and women are equally affected if the condition is from a gastrointestinal infection.

- Age. It occurs most often in people between ages 20 and 40.

- Genetics. People who have a gene called HLA-B27 have a higher risk of getting reactive arthritis and of experiencing more severe and more long-lasting symptoms. But people who lack HLA-B27 can still get the condition.

- HIV infection. Having AIDS or being infected with HIV increases the risk of reactive arthritis.

Reactive arthritis tends to occur most often in men between ages 20 and 50. Some patients with reactive arthritis carry a gene called HLA-B27. Patients who test positive for HLA-B27 often have a more sudden and severe onset of symptoms. They also are more likely to have chronic (long-lasting) symptoms. Yet, patients who are HLA-B27 negative (do not have the gene) can still get reactive arthritis after exposure to an organism that causes it.

Patients with weakened immune systems due to HIV and AIDS can also develop reactive arthritis.

Reactive arthritis causes

Reactive arthritis is triggered by a bacterial infection, frequently a sexually transmitted genitals or urinary tract infection or food-borne bacterial infection, but it is separate from the infection and typically sets in after the infection has cleared. You might not be aware of the triggering infection if it causes mild symptoms or none at all. The bacteria that cause reactive arthritis are very common. The bacteria that commonly trigger reactive arthritis are Salmonella, Yersinia, Campylobacter, Shigella, and Chlamydia, but only a minority of people infected with them develop reactive arthritis. The bacteria cause arthritis by distorting your body’s defense against infections, as well as your genetic environment. How exactly each of these factors plays a role in the disease likely varies from patient to patient. Scientists do not fully understand why some people are predisposed to getting reactive arthritis.

Numerous bacteria can cause reactive arthritis. Some are transmitted sexually, and others are foodborne. The most common ones include:

Reactive arthritis isn’t contagious. However, the bacteria that cause it can be transmitted sexually or in contaminated food. Only a few of the people who are exposed to these bacteria develop reactive arthritis.

Genetics seems to partly explain susceptibility to reactive arthritis, as many affected individuals have a gene called HLA-B27. However, many people who get reactive arthritis lack the HLA-B27 genetic marker so there are other, as yet unknown, genetic and environmental contributing factors.

Risk factors for reactive arthritis

Certain factors increase your risk of reactive arthritis:

- Age. Reactive arthritis occurs most frequently in adults between the ages of 20 and 40.

- Sex. Women and men are equally likely to develop reactive arthritis in response to foodborne infections. However, men are more likely than are women to develop reactive arthritis in response to sexually transmitted bacteria.

- Hereditary factors. A specific genetic marker has been linked to reactive arthritis. But most people who have this marker never develop the condition.

Reactive arthritis prevention

Genetic factors appear to play a role in whether you’re likely to develop reactive arthritis. Though you can’t change your genetic makeup, you can reduce your exposure to the bacteria that may lead to reactive arthritis.

Store your food at proper temperatures and cook it properly. Doing these things help you avoid the many foodborne bacteria that can cause reactive arthritis, including salmonella, shigella, yersinia and campylobacter. Some sexually transmitted infections can trigger reactive arthritis. Use condoms to help lower your risk.

Reactive arthritis symptoms

Some people with reactive arthritis have mild symptoms, while others have severe symptoms that limit daily activities. The signs and symptoms of reactive arthritis typically start 1 to 6 weeks after exposure to a triggering infection of the digestive or urinary tract or genitals, but the infection has usually resolved by the time symptoms arise. The onset is typically fairly sudden, usually over the course of a few days.

Reactive arthritis is characterized by inflammation of the joints, eyes, and urinary tract, but not everyone with the condition will experience all three, or they might not occur at the same time.

The main symptoms of reactive arthritis are:

- Joint pain and stiffness. The joint pain associated with reactive arthritis most commonly occurs in the knees, ankles and feet. Pain may also occur in the heels, low back or buttocks.

- Joints may become painful, red, and swollen, especially the large joints of the lower limbs, such as the knees and ankles. Morning stiffness or nighttime pain is typical. The affected joints are usually on one side of the body. There may be pain in the lower back and buttocks as well.

- Pain in the heel or foot pain is a sign of enthesitis (inflammation at a place where a tendon or ligament attaches to a bone).

- Swollen, inflamed, painful fingers or toes (dactylitis) may also occur.

- Eye inflammation. Many people who have reactive arthritis also develop eye inflammation (conjunctivitis).

- Conjunctivitis (inflammation of the transparent layer that covers the white part of the eye and lines the eyelids) and uveitis (inflammation of the middle part of the eye) can cause redness, pain, burning, itching, crusted eyelids, blurred vision, or sensitivity to light.

- Inflammation of the urinary tract. Increased frequency and discomfort during urination may occur, as can inflammation of the prostate gland or cervix.

- This symptom is more common when reactive arthritis happens after an infection of the genitals or urinary tract.

- In women, urinary tract inflammation can develop into inflammation of the cervix, fallopian tubes, vulva, or vagina.

- Increased urinary frequency and burning while urinating are signs of urinary tract inflammation.

- Enthesitis or inflammation of tendons and ligaments where they attach to bone. This happens most often in the heels and the sole of the feet.

- Swollen toes or fingers. In some cases, toes or fingers might become so swollen that they look like sausages.

- Low back pain. The pain tends to be worse at night or in the morning.

Other symptoms of reactive arthritis include:

- Skin problems. Reactive arthritis can affect skin in a variety of ways, including small ulcers in the mouth and a rash on the soles of the feet and palms of the hands. Skin rash (keratoderma blennorrhagica) consisting of reddish, raised bumps, usually on the palms or soles. The bumps may merge, forming a larger scaly rash.

- Fatigue or feeling generally unwell.

- Fever.

- Weight loss.

- Diarrhea and abdominal pain.

- In men, small, painless ulcers on the penis.

- Thickened nails.

The symptoms of reactive arthritis often clear up on their own within a few weeks or months, but they may become chronic (long-lasting) in some people.

Reactive arthritis diagnosis

Reactive arthritis diagnosis is largely based on your symptoms and clinical features on physical exam typical of reactive arthritis. During the physical exam, your doctor is likely to check your joints for swelling, warmth and tenderness, and test range of motion in your spine and affected joints. Your doctor might also check your eyes for inflammation and your skin for rashes.

If indicated, doctors might order a test for Chlamydia infection or test for the HLA-B27 gene. The test for Chlamydia uses a urine sample or a swab of the genitals. Having HLA-B27 is consistent with having reactive arthritis, but it is not definitive as people who test HLA-B27 negative can still have reactive arthritis, and not everyone who tests HLA-B27 positive has the condition.

Your doctor might recommend that a sample of your blood be tested for:

- Evidence of past or current infection

- Signs of inflammation.

- Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (sed rate) and C-reactive protein. These blood tests are measures of inflammation, but they are not specific for reactive arthritis. A positive test result can indicate any inflammatory disorder. A negative test result does not rule out reactive arthritis because these markers are usually not elevated in the chronic form of the condition.

- Antibodies associated with other types of arthritis.

- Rheumatoid factor (RF) and anticyclic citrullinated peptide (anti-CCP) antibody tests, which are associated with rheumatoid arthritis.

- Antinuclear antibody (ANA) test, which is associated with systemic lupus erythematosus.

- A genetic marker linked to reactive arthritis

Bacterial cultures

- Culturing your stool and urine specimens may reveal the presence of bacteria that frequently trigger reactive arthritis. But a negative result is not conclusive because in most cases, the infection has cleared by the time arthritic symptoms arise.

Joint fluid tests