Anterior interosseous nerve syndrome

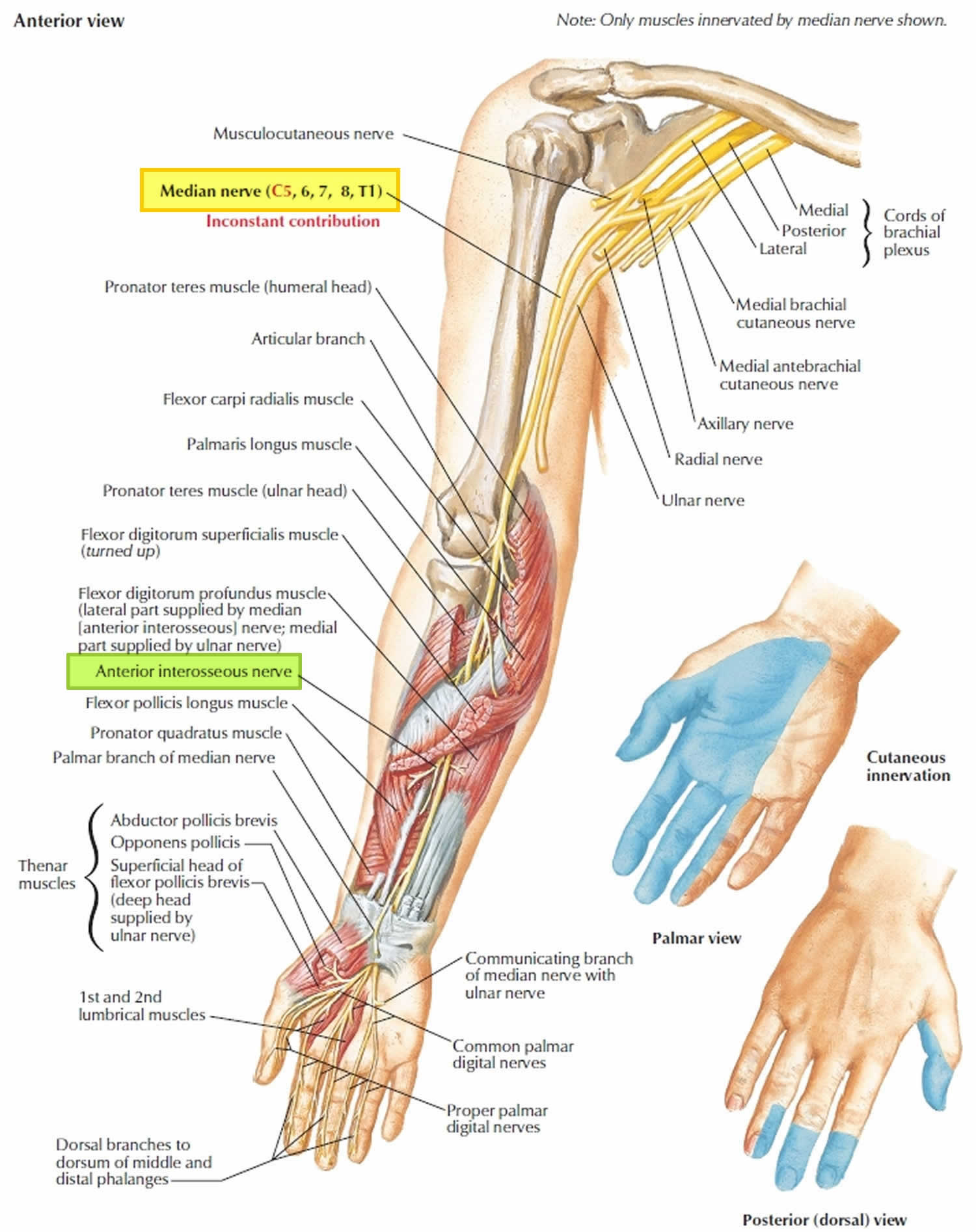

Anterior interosseous nerve syndrome also called Kiloh-Nevin syndrome or anterior interosseous syndrome, is a rare pure motor neuropathy that comprises less than 1% of all upper extremity nerve palsies, arising due to compression or inflammation of the anterior interosseous nerve of the forearm 1. The anterior interosseous nerve is purely a motor branch of the median nerve (it is the last major branch of the median nerve) that arises from its dorsomedial aspect, just inferior to the elbow, approximately 5–8-cm distal to the lateral epicondyle and 4 cm distal to the medial epicondyle 2. Anterior interosseous nerve runs deep in the forearm along the anterior interosseous membrane with the anterior interosseous artery. The anterior interosseous nerve innervates three muscles in the forearm: flexor pollicis longus, flexor digitorum profundus to the index and middle fingers and the pronator quadratus. Paresis or paralysis of the anterior interosseous nerve manifests clinically as weakness in the flexion of the interphalangeal joint of the thumb or the distal interphalangeal joints of the index and long fingers. An isolated anterior interosseous nerve palsy of these muscles is known as anterior interosseous nerve syndrome.

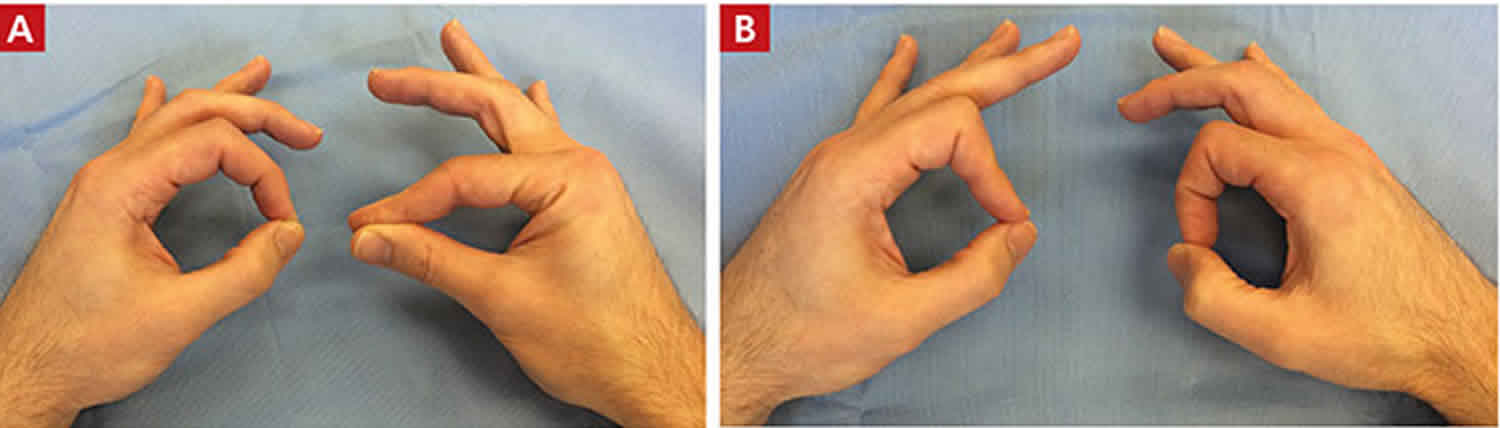

Patients with compression of the anterior interosseous nerve present with forearm discomfort similar to that in the pronator teres syndrome, but without any sensory deficit. Motor weakness and paralysis in the flexor pollicis longus, flexor digitorum profundus, and pronator quadratus muscles results in a characteristic pinch deformity and inability to make a fist (see the videos below). The common locations for anterior interosseous nerve entrapment are at the tendinous origin of the flexor digitorum superficialis muscle to the middle finger, at an accessory head of the flexor pollicis longus muscle, and at the tendinous origin of the deep head of the pronator teres muscle. Anterior interosseous nerve paralysis has also been reported as a result of trauma and injuries, such as fractures, lacerations, and penetrating wounds.

Once the diagnosis of anterior interosseous nerve syndrome is made, observation with an avoidance of aggravating activities, rest, and anti-inflammatory medication for several months has been suggested before decompression 3. Most patients with anterior interosseous nerve syndrome have an improvement without any surgical intervention 4. There is a role for physiotherapy and this should be directed specifically towards the pattern of pain and symptoms. Soft tissue massage, stretches and exercises in order to directly mobilise the nerve tissue may be used. Spinner et al. 5 recommended exploration if no signs of clinical and electromyographical improvement occur within 6–8 weeks. Nigst and Dick 6 recommended operative treatment in patients in whom there was no improvement after the conservative treatment for 8 weeks, since surgical decompression reduces the time needed for recovery. Hill et al. 7 recommended that exploration and external neurolysis be undertaken when there is no clinical and/or electromyographical improvement by 12 weeks after onset. However, spontaneous recovery in a later course has been described by several authors 4, 8, 9. For patients who have a space-occupying mass in the area, or who fail a several month course of nonsurgical treatment, surgical decompression has been recommended 4. Randomized controlled trials concerning the ideal duration of nonsurgical management and the timing of surgical intervention are still missing. In the absence of evidence suggesting neuritis, most authors still recommend a trial of conservative management for at least 12 weeks 9.

Figure 1. Anterior interosseous nerve

Anterior interosseous nerve syndrome causes

There are several documented causes of anterior interosseous nerve syndrome, the pathophysiology of which remains unclear. Causes for anterior interosseous nerve palsy can be divided into either traumatic or spontaneous (non traumatic) 10. Traumatic causes include: penetrating injuries, forearm fractures, venipuncture 11, cast fixation, slings 12, dressings 13, and a complication of open reduction and fixation of fractures 14. Anterior interosseous nerve dysfunction has been reported after elbow arthroscopy 15 and shoulder arthroscopy 16. The commonest of the spontaneous (non traumatic) causative factors are compression neuropathy 17, compartment syndrome 18 and brachial plexus neuritis (Kiloh-Nevin syndrome or neuralgic amyotrophy) 19.

The anterior interosseous nerve is susceptible to entrapment by soft tissue and by vascular and bony structures. According to Spinner 20, anterior interosseous nerve is vulnerable to injury or compression by the following:

- a tendinous origin of the deep head of pronator teres,

- a tendinous origin of flexor digitorum superficialis to the middle finger,

- thrombosis of the ulnar collateral vessels which cross it,

- accessory muscles and tendons from flexor digitorum superficialis,

- an aberrant radial artery,

- a thrombosed radial artery branch in the mid-forearm,

- a thrombosed ulnar artery,

- tendinous bands and osseous spurs,

- a tendinous origin of palmaris longus or flexor carpi radialis brevis,

- lacertus fibrosus,

- an enlarged bicipital tendon bursa.

Furthermore, the anterior interosseous nerve is prone to entrapment by anatomical variants such as an accessory head of flexor pollicis longus (Gantzer’s muscle); an anomalous head of the flexor pollicis longus 21.

Collins and Weber 22 considered entrapment to be by far the most common cause of anterior interosseous nerve palsy. Hill et al. 7 observed it in 24 of 28 cases of incomplete palsy. Schantz and Riegels-Nielson 23 found evidence of nerve compression in nine of 15 patients.

An incomplete syndrome in which only the flexor pollicis longus or the flexor digitorum profundus of the index finger is paralysed must be distinguished from flexor tendon rupture, flexor tendon adherence or adhesion, and stenosing tenosynovitis. The anterior interosseous nerve is usually compressed by fibrous bands that most commonly originate from the deep head of the pronator teres and the brachialis fascia 24.

Differential diagnosis consists of a noncompressive neuropathy, such as brachial neuritis, which may mimic the clinical manifestations of an anterior interosseous nerve neuropathy 25. A rupture of the flexor pollicis longus tendon is also possible in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. To exclude this differential diagnosis, the wrist should be passively flexed and extended to confirm that the patient has an intact tenodesis effect. A sudden onset of anterior interosseous nerve compression symptoms associated with a viral prodrome suggests the diagnosis of such a viral neuritis (Parsonage–Turner syndrome) 25.

Anterior interosseous nerve syndrome signs and symptoms

True anterior interosseous nerve syndrome presentation will present with motor deficits only. Patients with anterior interosseous nerve syndrome are typically unable to form an “O” by using the index finger and thumb due to paralysis of flexor pollicis longus and the radial flexor digitorum profundus (impaired flexion of the interphalangeal joint of the thumb and the distal interphalangeal joint of the index finger). The patients will lose the ability to button their shirts or turn on their car keys to start it. On physical examination, the Pinch Grip test is positive where patients will not be able to demonstrate the “OK” sign, instead clamping the sheet between an extended thumb and index finger 26. No sensory changes should be appreciated. Most patients experience poorly localized pain in the forearm and cubital fossa. This pain is usually the primary complaint. There are no sensations of numbness, tingling, or sensory deficits. The absence of sensory deficits in anterior interosseous nerve syndrome differentiates it from carpal tunnel syndrome and other nerve palsies (e.g., pronator syndrome, Parsonage-Turner syndrome), which usually lead to decreased sensation, tingling, or numbness in the upper limb. The flexor pollicis longus, the radial part of the flexor digitorum profundus and pronator quadratus are affected in complete anterior interosseous nerve syndrome. However, incomplete anterior interosseous nerve syndrome occurs when isolated flexor pollicis longus or flexor digitorum profundus of the index finger is either paretic or paralyzed 27. An isolated weakness of the thumb may indicate isolated involvement of the particular fascicle that innervates the flexor pollicis longus 28.

Anterior interosseous nerve syndrome diagnosis

Important elements in the diagnosis of anterior interosseous nerve syndrome are electrodiagnostic studies. They confirm the diagnosis and objectively assess the severity of the neuropathy. Sensory nerve conduction studies of the median nerve should be normal as there is no sensory innervation to the anterior interosseous nerve. More proximal lesions can be ruled out by electromyography (EMG). Also, EMG is helpful for distinguishing anterior interosseous nerve syndrome from a flexor tendon rupture in patients with severe rheumatoid disease who have such limited wrist motion that the determination of an intact tenodesis effect is impossible. MRI is not commonly used in the diagnosis of anterior interosseous nerve syndrome, although there is literature describing the MRI findings associated with anterior interosseous nerve syndrome in which increased signal intensity can be seen in the anterior interosseous nerve-innervated muscles on T2-weighted, fat-saturated images or short inversion time inversion recovery sequences 29. On fluid-sensitive sequences such as short tau inversion recovery (STIR), proton density or T2-weighted fat saturated images, an increased signal intensity within some or all muscle groups innervated by the anterior interosseous nerve could be seen. The most reliable finding is increased signal intensity within the pronator quadratus 30:1155–1162. Epub 2007 Oct 16.)).

Anterior interosseous nerve syndrome treatment

While most cases of anterior interosseous nerve syndrome improve spontaneously without surgical intervention, its optimal treatment remains controversial. Conservative management with rest, analgesia (steroids or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [NSAIDs]), physiotherapy and splinting has been generally advocated 31. Meanwhile, early surgical exploration and neurolysis have demonstrated promising results 32. Other options include observation for spontaneous recovery, in which surgical intervention is indicated after 3 months of failed recovery 33. Although surgical decompression did not achieve full recovery, improvement of power has been achieved.

If motor function does not recover, tendon transfer will restore the function satisfactorily. The brachioradialis is a good substitute for restoring flexion of the interphalangeal joint of the thumb. The transfer of the tendon of flexor digitorum profundus of the ring or middle finger to that of the index finger at the wrist can provide satisfactory flexion of the distal phalanx of the index finger 34. Schantz and Riegels-Nielson 23 recommend delay in the use of tendon transfer until one year after the onset of palsy. However, further investigations are warranted to delineate the optimal treatment of anterior interosseous nerve syndrome.

Conservative management

The general consensus for managing anterior interosseous nerve syndrome includes a period of rest, observation, and splinting of the elbow near 90 degrees of flexion (or position of most comfort for the patient). The majority of patients will experience improvement between 6 and 12 weeks of activity modification.

Other modalities to consider include NSAIDs and physical therapy modalities (including pain modalities and massage techniques if tolerated)

Surgical decompression

Surgical treatment consists of exploration, neurolysis, and decompression after several months of failed nonoperative modalities. The literature reports 75% or greater positive outcomes following surgery, with higher rates reported in patients with an identifiable, clear space-occupying mass.

Unless a clear cause is identified, surgical intervention is typically offered only in select cases, and the option is discussed following at least three months of failed conservative treatment 35.

During median nerve surgical decompression, meticulous dissection is necessary to establish exact sites of compression. It is critical in the identification and release of compressing edges or fibrous bands 36.

Anterior interosseous nerve syndrome prognosis

Anterior interosseous nerve syndrome prognosis is usually good, and most cases don’t require surgical treatment 37. If conservative therapy fails beyond three months, surgery might be offered in select cases.

- Wu F, Ismaeel A, Siddiqi R. Anterior interosseous nerve palsy following the use of elbow crutches. N Am J Med Sci. 2011;3(6):296-298. doi:10.4297/najms.2011.3296 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3336923[↩]

- Aljawder A, Faqi MK, Mohamed A, Alkhalifa F. Anterior interosseous nerve syndrome diagnosis and intraoperative findings: A case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2016;21:44-47. doi:10.1016/j.ijscr.2016.02.021 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4802332[↩]

- Lubahn J, Cermak M. Uncommon nerve compression syndromes of the upper extremity. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1998;6:378–386.[↩]

- Miller-Breslow A, Terrono A, Millender LH. Nonoperative treatment of anterior interosseous nerve paralysis. J Hand Surg. 1990;15A:493–496.[↩][↩][↩]

- Spinner M. The anterior interosseous nerve syndrome: with special attention to its variations. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1970;52A:84–94.[↩]

- Nigst H, Dick W. Syndromes of compression of the median nerve in the proximal forearm (pronator teres syndrome; anterior interosseous nerve syndrome) Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1979;93:307–312. doi: 10.1007/BF00450231[↩]

- Hill NA, Howard FM, Huffer BR. The incomplete anterior interosseous nerve syndrome. J Hand Surg Am. 1985;10:4–16.[↩][↩]

- Seror P. Anterior interosseous nerve lesions: clinical and electrophysiological features. J Bone Joint Surg. 1996;78B:238–241.[↩]

- Sood MK, Burke FD. Anterior interosseous nerve palsy: a review of 16 cases. J Hand Surg. 1997;B22:64–68.[↩][↩]

- Komaru Y, Inokuchi R. Anterior interosseous nerve syndrome. QJM. 2017;110(4):243. doi:10.1093/qjmed/hcw227[↩]

- Puhaindran ME, Wong HP. A case of anterior interosseous nerve syndrome after peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) line insertion. Singap Med J. 2003;44:653–655.[↩]

- O’Neill DB, Zarins B, Gelberman RH, Keating TM, Louis D. Compression of the anterior interosseous nerve after use of a sling for dislocation of the acromioclavicular joint: a report of two cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1990;72:1100–1102.[↩]

- Casey PJ, Moed BR. Fractures of the forearm complicated by palsy of the anterior interosseus nerve caused by a constrictive dressing. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1997;79:122–124.[↩]

- Joist A., Joosten U., Wetterkamp D. Anterior interosseous nerve compression after supracondylar fracture of the humerus: a metaanalysis. J. Neurosurg. 1999 Jun;90(6):1053–1056.[↩]

- Kelly EW, Morrey BF, O’Driscoll SW. Complications of elbow arthroscopy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83:25–34.[↩]

- Sisco M, Dumanian GA. Anterior interosseous nerve syndrome following shoulder arthroscopy. J Bone Joint Surg. 2007;89A:392–395. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00445[↩]

- Lipscomb PR, Burleson RJ. Vascular and neural complications in supracondylar fractures in children. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1955;37A:487–492.[↩]

- Xing SG, Tang JB. Entrapment neuropathy of the wrist, forearm, and elbow. Clin Plast Surg. 2014 Jul;41(3):561-88.[↩]

- Schollen W., Degreef I., De Smet L. Kiloh-Nevin syndrome: a compression neuropathy or brachial plexus neuritis? Acta Orthop. Belg. 2007;73(3):315–318.[↩]

- Spinner P.C., Amadio R.J. Compressive neuropathies of the upper extremity. Clin. Plast. Surg. 2003;30:155–173.[↩]

- Degreef I., De Smet L. Anterior interosseous nerve paralysis due to Gantzer’s muscle. Acta Orthop. Belg. 2004;70:482–484.[↩]

- Collins DN, Weber ER. Anterior interosseous nerve syndrome. South Med J. 1983;76:1533–1537. doi: 10.1097/00007611-198312000-00019[↩]

- Schantz K, Riegels-Nielsen P. The anterior interosseous nerve syndrome. J Hand Surg Br. 1992;17(5):510–512. doi: 10.1016/S0266-7681(05)80232-3[↩][↩]

- Spinner M. Injuries to the major branches of peripheral nerves of the forearm. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1978. pp. 160–227.[↩]

- Parsonage M, Turner J. Neuralgic amyotrophy: the shoulder-girdle syndrome. Lancet. 1948;1:973–978. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(48)90611-4[↩][↩]

- Berger R.A. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2004. Hand Surgery. ISBN: 0781728746.[↩]

- Hill NA, Howard FM, Huffer BR. The incomplete anterior interosseous nerve syndrome. J Hand Surg Am. 1985;10(1):4-16. doi:10.1016/s0363-5023(85)80240-9[↩]

- Proudman TW, Menz PJ. An anomaly of the median artery associated with the anterior interosseous nerve syndrome. J Hand Surg Br. 1992;17(5):507-509. doi:10.1016/s0266-7681(05)80231-1[↩]

- Dunn AJ, Salonen DC, Anastakis DJ. MR imaging findings of anterior interosseous nerve lesions. Skelet Radiol. 2007;36:1155–1162. doi: 10.1007/s00256-007-0382-7[↩]

- Dunn A.J.1, Salonen D.C., Anastakis D.J. MR imaging findings of anterior interosseous nerve lesions. Skeletal Radiol. 2007;36(December (12[↩]

- Seki M., Nakamura H., Kono H. Neurolysis is not required for young patients with a spontaneous palsy of the anterior interosseous nerve: retrospective analysis of cases managed non-operatively. J. Bone Joint Surg. Br. 2006;88(12):1606–1609.[↩]

- Schantz K., Riegels-Nielsen P. The anterior interosseous nerve syndrome. J. Hand Surg. Br. 1992;17(5):510–512.[↩]

- Ulrich D., Piatkowski A., Pallua N. Anterior Interosseous nerve syndrome: retrospective analysis of 14 patients. Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. 2011;131(11):1561–1565.[↩]

- Nagano A. Spontaneous anterior interosseous nerve palsy. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2003;85:313–318. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.85B3.14147[↩]

- Strohl AB, Zelouf DS. Ulnar Tunnel Syndrome, Radial Tunnel Syndrome, Anterior Interosseous Nerve Syndrome, and Pronator Syndrome. Instr Course Lect. 2017 Feb 15;66:153-162.[↩]

- Schulte-Mattler WJ, Grimm T. [Common and not so common nerve entrapment syndromes: diagnostics, clinical aspects and therapy]. Nervenarzt. 2015 Feb;86(2):133-41.[↩]

- Akhondi H, Varacallo M. Anterior Interosseous Syndrome. [Updated 2020 Aug 10]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK525956[↩]