Anterior shoulder pain

Anterior shoulder pain or pain in the front of the shoulder happens when your shoulder joint, muscles, and/or tendons get injured or strained. Your shoulder is made up of several joints combined with tendons and muscles that allow a great range of motion in your arm. Because so many different structures make up the shoulder, it is vulnerable to many different problems. The rotator cuff is a frequent source of anterior shoulder pain. Anterior shoulder pain is more common than posterior shoulder pain or pain in the back of the shoulder and it normally occurs as a result of injury to the glenohumeral (shoulder) joint and the resulting inflammation of the tendons attached to it, causing the rotator cuff to be unable to support the glenohumeral joint. This causes pain in the biceps and the front shoulder.

Shouder anatomy

Your shoulder is a complex joint that is capable of more motion than any other joint in your body. It is made up of three bones: your upper arm bone (humerus), your shoulder blade (scapula), and your collarbone (clavicle).

Your arm is kept in your shoulder socket by your rotator cuff. These muscles and tendons form a covering around the head of your upper arm bone and attach it to your shoulder blade.

There is a lubricating sac called a bursa between the rotator cuff and the bone on top of your shoulder (acromion). The bursa allows the rotator cuff tendons to glide freely when you move your arm.

The shoulder region includes the glenohumeral joint, the acromioclavicular joint, the sternoclavicular joint and the scapulothoracic articulation (Figure 1). The glenohumeral joint capsule consists of a fibrous capsule, ligaments and the glenoid labrum. Because of its lack of bony stability, the glenohumeral joint is the most commonly dislocated major joint in the body. Glenohumeral stability is due to a combination of ligamentous and capsular constraints, surrounding musculature and the glenoid labrum. Static joint stability is provided by the joint surfaces and the capsulolabral complex, and dynamic stability by the rotator cuff muscles and the scapular rotators (trapezius, serratus anterior, rhomboids and levator scapulae).

Scapular stability collectively involves the trapezius, serratus anterior and rhomboid muscles. The levator scapular and upper trapezius muscles support posture; the trapezius and the serratus anterior muscles help rotate the scapula upward, and the trapezius and the rhomboids aid scapular retraction.

Ball and socket. The head of your upper arm bone fits into a rounded socket in your shoulder blade. This socket is called the glenoid. A slippery tissue called articular cartilage covers the surface of the ball and the socket. It creates a smooth, frictionless surface that helps the bones glide easily across each other.

The glenoid is ringed by strong fibrous cartilage called the labrum. The labrum forms a gasket around the socket, adds stability, and cushions the joint.

Shoulder capsule. The joint is surrounded by bands of tissue called ligaments. They form a capsule that holds the joint together. The undersurface of the capsule is lined by a thin membrane called the synovium. It produces synovial fluid that lubricates the shoulder joint.

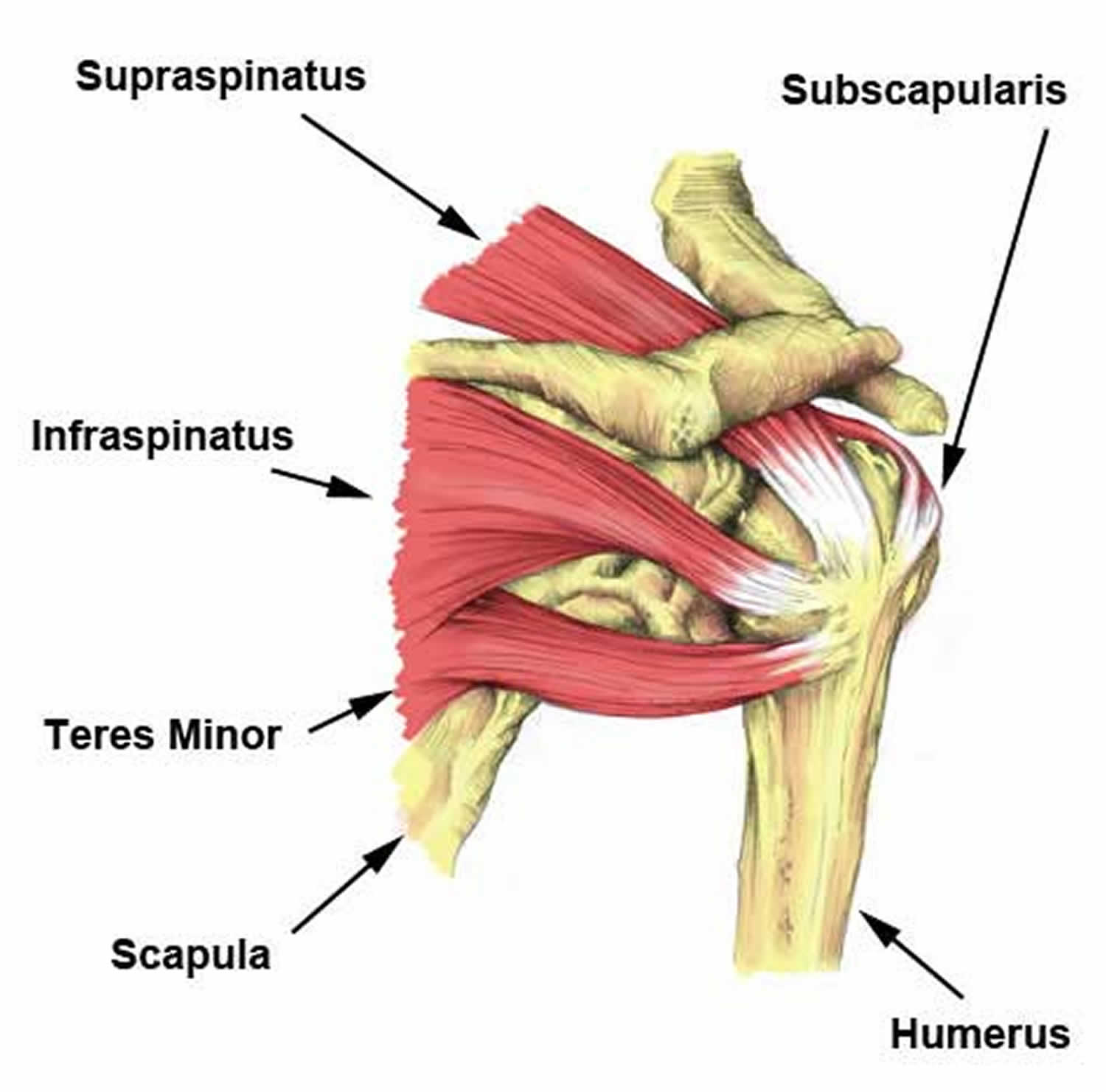

Rotator cuff. The rotator cuff is composed of four muscles: the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor and subscapularis (Figure 2). Four tendons surround the shoulder capsule and help keep your arm bone centered in your shoulder socket. This thick tendon material is called the rotator cuff. The cuff covers the head of the humerus and attaches it to your shoulder blade. The subscapularis facilitates internal rotation, and the infraspinatus and teres minor muscles assist in external rotation. The rotator cuff muscles depress the humeral head against the glenoid. With a poorly functioning (torn) rotator cuff, the humeral head can migrate upward within the joint because of an opposed action of the deltoid muscle.

Bursa. There is a lubricating sac called a bursa between the rotator cuff and the bone on top of your shoulder (acromion). The bursa helps the rotator cuff tendons glide smoothly when you move your arm.

Figure 1. Shoulder anatomy

Figure 2. Anterior shoulder muscles (rotator cuff muscles & tendons)

Anterior shoulder pain causes

Your shoulder joints are composed of bones – the humerus, the glenoid, the scapula, the acromion, and the clavicle combined with the muscles and tendons that form your rotator cuff, which is the all-important collection of bones and tissues that keeps your upper arm bone firmly tucked within your shoulder socket.

Injuries to the rotator cuff can cause anything from dull aches and pain and the associated issues with movement to severe pain and even immobility.

When your rotator cuff is injured or inflamed, you can experience anterior shoulder pain. It doesn’t matter how old you are or how active you are, front shoulder pain can hamper your mobility and have a negative effect on your lifestyle. The pain can also be worse at night.

Shoulder injuries like fractures, bone breakage, injured tendons or muscles are the typical causes of anterior shoulder pain. Repetitive strain on the muscles like lifting heavy objects or participating in sports that may strain the shoulder joints is another potential cause, and arthritis symptoms in the shoulder can also result in pain that radiates from the shoulder to the neck.

Immediately assessing how severe these types of injuries are goes a long way towards finding effective treatments, which may range from cold therapy and pain meds to physiotherapy and even shoulder surgery.

The presence of another preexisting health condition like arthritis that causes shoulder soreness can also result in front shoulder pain.

Anterior shoulder pain can be also be the result of high muscle tension at key trigger points.

Common types of anterior shoulder pain include:

- Acromioclavicular joint injury – Localized pain in the clavicle caused by the overuse of the shoulder.

- Adhesive capsulitis – Stiffness in the shoulder joint that can lead to the loss of movement during abduction and external rotation.

- Biceps tendonitis – When the tendons and muscles are damaged by lifting up and carrying heavy objects.

- Shoulder impingement syndrome – When the tendons on your shoulder blade rub together, causing pain in the front of the shoulder.

- Labral tear – Torn cartilage in the shoulder region, causing deep, severe pain.

- Rotator cuff tear or tendinopathy – An injury causing severe pain when you rotate your shoulder and the general weakening of the tendons in your shoulder joints.

- Shoulder arthritis – This progressive condition causes pain in the shoulder and surrounding areas and can be at least partially treated by removing the loose fragments of bone cartilage, and other tissue from the shoulder joint.

The rotator cuff is a common source of pain in the shoulder. Pain can be the result of:

- Tendinitis. The rotator cuff tendons can be irritated or damaged.

- Bursitis. The bursa can become inflamed and swell with more fluid causing pain.

- Impingement. When you raise your arm to shoulder height, the space between the acromion and rotator cuff narrows. The acromion can rub against (or “impinge” on) the tendon and the bursa, causing irritation and pain.

Rotator cuff pain is common in both young athletes and middle-aged people. Young athletes who use their arms overhead for swimming, baseball, and tennis are particularly vulnerable. Those who do repetitive lifting or overhead activities using the arm, such as paper hanging, construction, or painting are also susceptible.

Pain may also develop as the result of a minor injury. Sometimes, it occurs with no apparent cause.

Anterior shoulder pain prevention

While injuries and other shoulder conditions often cannot be helped, there are some things you can do to prevent or decrease the possibility of front shoulder pain, including things such as:

- Working on your overall strength, flexibility, and fitness

- Performing proper stretches and warm up work before any significant physical activity

- Allowing for plenty of recovery time between workouts

- Working with a professional and accredited physical trainer when you do work out

- Using proper gear and equipment during workouts and any sports you participate in.

Anterior shoulder pain symptoms

Some of the common symptoms of this type of shoulder pain are swelling, tenderness, and pain in front shoulder joint, severe pain and stiffness in the shoulder, a continuous or ongoing feeling of discomfort, decreased strength, and limited mobility of the affected shoulder, including the inability to lift heavier objects or difficulty lowering that arm.

Rotator cuff pain commonly causes local swelling and tenderness in the front of the shoulder. You may have pain and stiffness when you lift your arm. There may also be pain when the arm is lowered from an elevated position.

Beginning symptoms may be mild. Patients frequently do not seek treatment at an early stage. These symptoms may include:

- Minor pain that is present both with activity and at rest

- Pain radiating from the front of the shoulder to the side of the arm

- Sudden pain with lifting and reaching movements

- Athletes in overhead sports may have pain when throwing or serving a tennis ball

As the problem progresses, the symptoms increase:

- Pain at night

- Loss of strength and motion

- Difficulty doing activities that place the arm behind the back, such as buttoning or zippering

If the pain comes on suddenly, the shoulder may be severely tender. All movement may be limited and painful.

Self-massaging areas that are painful can be a way to start to assess the issue before you can see a medical professional – sensitivity to pressure and pain are a sign that your shoulder muscles are not healthy.

Anterior shoulder pain diagnosis

Determining the cause of anterior shoulder pain can be complicated. After discussing your symptoms and medical history, your doctor will examine your shoulder. He or she will check to see whether it is tender in any area or whether there is a deformity. To measure the range of motion of your shoulder, your doctor will have you move your arm in several different directions. He or she will also test your arm strength.

Your doctor will check for other problems with your shoulder joint. He or she may also examine your neck to make sure that the pain is not coming from a “pinched nerve,” and to rule out other conditions, such as arthritis.

Shoulder exam

Specifically, rotator cuff strength and/or pathology can be assessed via the following examinations:

1. Supraspinatus

- Jobe’s test: a positive test is pain/weakness with resisted downward pressure while the patient’s shoulder is at 90 degrees of forward flexion and abduction in the scapular plane with the thumb pointing toward the floor.

- Drop arm test: the patient’s shoulder is brought into a position of 90 degrees of shoulder abduction in the scapular plane. The examiner initially supports the limb and then instructs the patient to slowly adduct the arm to the side of the body. A positive test includes the patient’s inability to maintain the abducted position of the shoulder and/or an inability to adduct the arm to the side of the trunk in a controlled manner.

2. Infraspinatus

- Strength testing is performed while the shoulder is positioned against the side of the trunk, the elbow is flexed to 90 degrees, and the patient is asked to externally rotate (external rotation) the arm while the examiner resists this movement.

- External rotation lag sign: the examiner positions the patient’s shoulder in the same position, and while holding the wrist, the arm is brought into maximum external rotation. The test is positive if the patient’s shoulder drifts into internal rotation once the examiner removes the supportive external rotation force at the wrist.

3. Teres Minor

- Strength testing is performed while the shoulder positioned at 90 degrees of abduction and the elbow is also flexed to 90 degrees. Teres minor is best isolated for strength testing in this position while external rotation is resisted by the examiner.

- Hornblower’s sign: the examiner positions the shoulder in the same position and maximally external rotations the shoulder under support. A positive test occurs when the patient is unable to hold this position, and the arm drifts into internal rotation once the examiner removes the supportive external rotation force.

4. Subscapularis

- Internal rotation lag sign: the examiner passively brings the patient’s shoulder behind the trunk (about 20 degrees of extension) with the elbow flexed to 90 degrees. The examiner passively internal rotations the shoulder by lifting the dorsum of the handoff of the patient’s back while supporting the elbow and wrist. A positive test occurs when the patient is unable to maintain this position once the examiner releases support at the wrist (i.e., the arm is not maintained in internal rotation, and the dorsum of the hand drifts toward the back).

- Passive external rotation range of motion (ROM): a partial or complete tear of the subscapularis (SubSc) can manifest as an increase in passive external rotation compared to the contralateral shoulder.

- Lift-off test: more sensitive/specific for lower subscapularis pathology. In the same position as the internal rotation lag sign position, the examiner places the patient’s dorsum of the hand against the lower back and then resists the patient’s ability to lift the dorsum of the hand away from the lower back.

- Belly press: more sensitive/specific for upper subscapularis pathology. The examiner has the patient’s arm at 90 degrees of elbow flexion, and internal rotation testing is performed by the patient pressing the palm of his/her hand against the belly, bringing the elbow in front of the plane of the trunk. The elbow is initially supported by the examiner, and a positive test occurs if the elbow is not maintained in this position upon the examiner removing the supportive force.

5. External impingement

- Neer impingement sign: positive if the patient reports pain with passive shoulder forward flexion beyond 90 degrees.

- Neer impingement test: positive test occurs after a subacromial injection is given by the examiner and the patient reports improved symptoms upon repeating the forced passive forward flexion beyond 90 degrees.

- Hawkins test: positive test occurs with the examiner passively positioning the shoulder and elbow at 90 degrees of flexion in front of the body; the patient will report pain when the examiner passively internal rotation’s the shoulder.

6. Internal impingement

Internal impingement test: the patient is placed in a supine position and the shoulder is brought into terminal abduction and external rotation; a positive test consists of the reproduction of the patient’s pain.

Imaging tests

X-rays. Becauses x-rays do not show the soft tissues of your shoulder like the rotator cuff, plain x-rays of a shoulder with rotator cuff pain are usually normal or may show a small bone spur. A special x-ray view, called an “outlet view,” sometimes will show a small bone spur on the front edge of the acromion.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and ultrasound. These studies can create better images of soft tissues like the rotator cuff tendons. They can show fluid or inflammation in the bursa and rotator cuff. In some cases, partial tearing of the rotator cuff will be seen.

Anterior shoulder pain treatment

The first goal of treating front shoulder pain is reducing the swelling and inflammation, alleviating the pain, and improving the range of motion and lifting capabilities of the affected shoulder joints. In planning your treatment, your doctor will consider your age, activity level, and general health.

Nonsurgical treatment

In most cases, initial treatment is nonsurgical. Although nonsurgical treatment may take several weeks to months, many patients experience a gradual improvement and return to function.

Rest. Your doctor may suggest rest and activity modification, such as avoiding overhead activities.

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Drugs like ibuprofen and naproxen reduce pain and swelling.

Physical therapy. A physical therapist will initially focus on restoring normal motion to your shoulder. Stretching exercises to improve range of motion are very helpful. If you have difficulty reaching behind your back, you may have developed tightness of the posterior capsule of the shoulder (capsule refers to the inner lining of the shoulder and posterior refers to the back of the shoulder). Specific stretching of the posterior capsule can be very effective in relieving pain in the shoulder.

Once your pain is improving, your therapist can start you on a strengthening program for the rotator cuff muscles.

Steroid injection. If rest, medications, and physical therapy do not relieve your pain, an injection of a local anesthetic and a cortisone preparation may be helpful. Cortisone is a very effective anti-inflammatory medicine. Injecting it into the bursa beneath the acromion can relieve pain.

Anterior shoulder pain exercises

Exercises that can help reduce anterior shoulder pain. There are three types of exercises that are commonly used to reduce pain in the front shoulder. These should be performed under the supervision of a trained medical professional such as a physical therapist upon the advice or prescription on an orthopedic shoulder surgeon.

These exercises include:

- Range of Motion Exercises – These movements help you achieve a full range of motion in your shoulder joints by ensuring your shoulders are moved in different directions. This helps your joints become more flexible and you’ll have more strength with a better sense of balance, helping to reduce your anterior shoulder pain. The most common range of motion exercises for shoulder pain are pendulum and flexion exercises.

- Stretching Exercises – Focusing on the flexibility and elasticity of the tendons in your shoulder joint, these exercises carefully and deliberately stretch and elongate the muscles and tendons, improving the range of motion and overall muscle control. The standard stretching movements are seating and standing flexion along with external rotations.

- Strengthening Exercises – Also referred to as strength training, these types of physiotherapy programs utilize resistance and weights to build up muscle strength and size in your shoulders, improving the stability of the joints.

Remember these particular types of exercises should only be done under the advice of your physician or surgeon and well after recovery since they can cause muscle fatigue and soreness, which could cause existing pain to become increasingly worse.

Common exercises include scapular depressions and abductions, shoulder flexions, internal rotations, external rotations, scapular protractions, scapular retractions, and shoulder extensions.

All these exercises should only be done after recovery from the initial injury and any corresponding surgery or other treatments.

Surgical treatment

When nonsurgical treatment does not relieve pain, your doctor may recommend surgery.

The goal of surgery is to create more space for the rotator cuff. To do this, your doctor will remove the inflamed portion of the bursa. He or she may also perform an anterior acromioplasty, in which part of the acromion is removed. This is also known as a subacromial decompression. These procedures can be performed using either an arthroscopic or open technique.

Arthroscopic technique

In arthroscopy, thin surgical instruments are inserted into two or three small puncture wounds around your shoulder. Your doctor examines your shoulder through a fiberoptic scope connected to a television camera. He or she guides the small instruments using a video monitor, and removes bone and soft tissue. In most cases, the front edge of the acromion is removed along with some of the bursal tissue.

Your surgeon may also treat other conditions present in the shoulder at the time of surgery. These can include arthritis between the clavicle (collarbone) and the acromion (acromioclavicular arthritis), inflammation of the biceps tendon (biceps tendonitis), or a partial rotator cuff tear.

Open surgical technique. In open surgery, your doctor will make a small incision in the front of your shoulder. This allows your doctor to see the acromion and rotator cuff directly.

Rehabilitation

After surgery, your arm may be placed in a sling for a short period of time. This allows for early healing. As soon as your comfort allows, your doctor will remove the sling to begin exercise and use of the arm.

Your doctor will provide a rehabilitation program based on your needs and the findings at surgery. This will include exercises to regain range of motion of the shoulder and strength of the arm. It typically takes 2 to 4 months to achieve complete relief of pain, but it may take up to a year.