What is aortic regurgitation

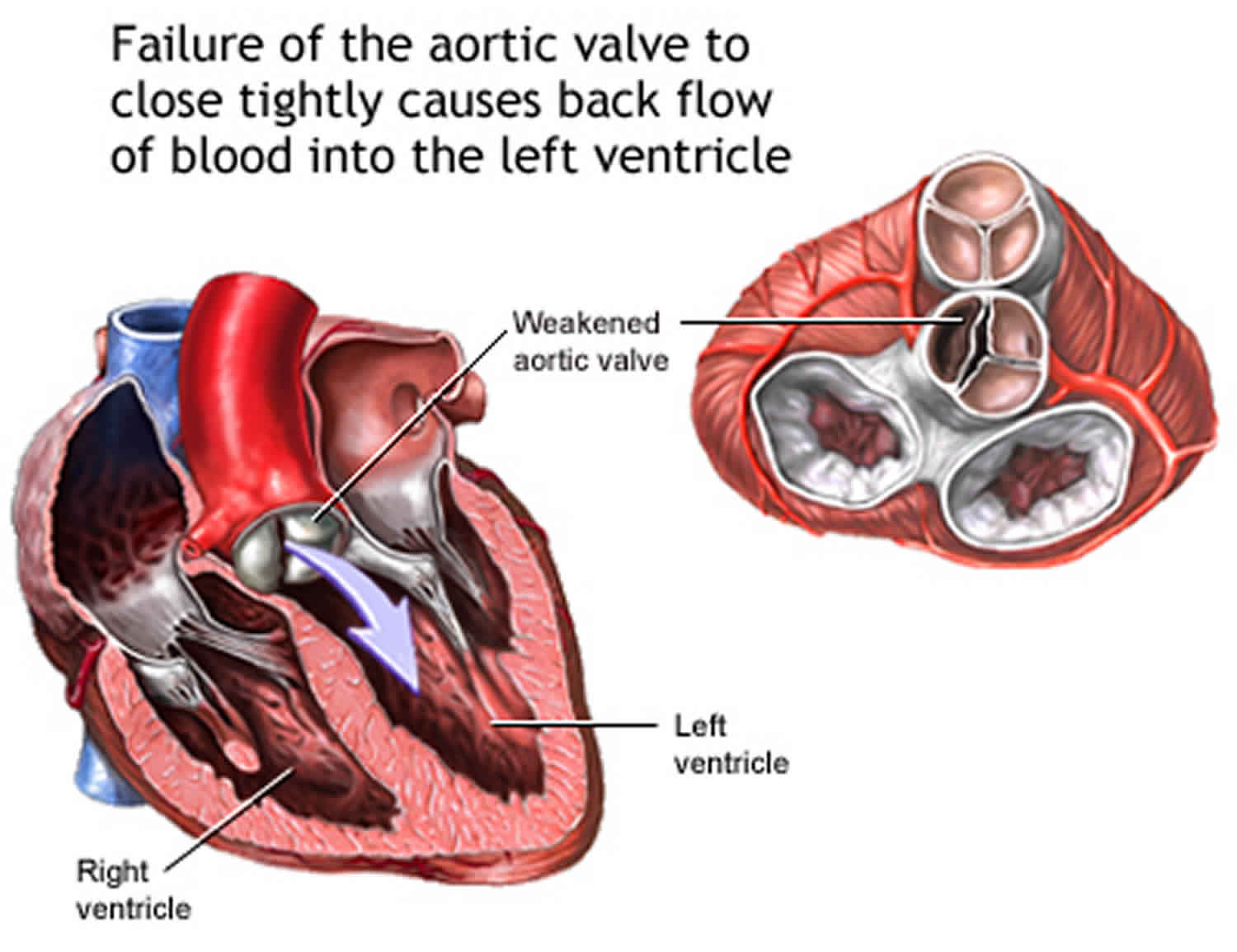

Aortic regurgitation also called aortic valve regurgitation, is a condition that occurs when your heart’s aortic valve doesn’t close tightly. Aortic regurgitation allows some of the blood that was pumped out of your heart’s main pumping chamber (left ventricle) to leak back into it. The leakage may prevent your heart from efficiently pumping blood to the rest of your body. As a result, you may feel fatigued and short of breath.

Aortic valve regurgitation can develop suddenly or over decades. Once aortic valve regurgitation becomes severe, surgery is often required to repair or replace the aortic valve. Causes of acute aortic regurgitation include type A aortic dissection extending to the valve or damage to leaflets from infectious or noninfectious endocarditis 1. The same pathologies most commonly cause chronic aortic regurgitation in developing countries as aortic stenosis; calcific disease, congenital bicuspid valve issues, and Marfan syndrome 1. Other less common causes include complications following percutaneous aortic balloon valvuloplasties and transcatheter aortic valve replacements as well as a slew of inflammatory disorders including but not limited to systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, and Takayasu arteritis. The most prevalent cause of chronic aortic regurgitation in developing countries is rheumatic heart disease 2.

Aortic regurgitation has an estimated prevalence of 4.9%, also increasing with age until the sixth decade when incidence begins to decrease. This number, however, may be artificially low because up to 75% of aortic stenosis patients may have some degree of regurgitation that goes unreported 3.

You may not need treatment if you have no symptoms or only mild symptoms. However, you will need to see a health care provider for regular echocardiograms.

If your blood pressure is high, you may need to take blood pressure medicines to help slow the worsening of aortic regurgitation.

Diuretics (water pills) may be prescribed for symptoms of heart failure.

In the past, most people with heart valve problems were given antibiotics before dental work or an invasive procedure, such as colonoscopy. The antibiotics were given to prevent an infection of the damaged heart. However, antibiotics are now used much less often.

You may need to limit activity that requires more work from your heart. Talk to your provider.

Surgery to repair or replace the aortic valve corrects aortic regurgitation. The decision to have aortic valve replacement depends on your symptoms and the condition and function of your heart.

You may also need surgery to repair the aorta if it is widened.

Aortic regurgitation causes

Any condition that prevents the aortic valve from closing completely can cause aortic regurgitation. In aortic valve regurgitation, the valve between the lower left heart chamber (left ventricle) and the main artery that leads to the body (aorta) doesn’t close properly, which causes some blood to leak backward into the left ventricle each time your heart beats. When a large amount of blood comes back, the heart must work harder to force out enough blood to meet the body’s needs. This forces the left ventricle to hold more blood, possibly causing it to enlarge and thicken. The left lower chamber of the heart widens (dilates) and the heart beats very strongly (bounding pulse). Over time, the heart becomes less able to supply enough blood to the body.

In the past, rheumatic fever was the main cause of aortic regurgitation. The use of antibiotics to treat strep infections has made rheumatic fever less common. Therefore, aortic regurgitation is more commonly due to other causes. These include:

- Age-related changes to the heart. Calcium deposits can build up on the aortic valve over time, causing the aortic valve’s cusps to stiffen. This can cause the aortic valve to become narrow, and it may also not close properly.

- Ankylosing spondylitis

- Aortic dissection

- Congenital (present at birth) heart valve disease. You may have been born with an aortic valve that has only two cusps (bicuspid valve) or fused cusps rather than the normal three separate cusps. In some cases a valve may only have one cusp (unicuspid) or four cusps (quadricuspid), but this is less common. These congenital heart defects put you at risk of developing aortic valve regurgitation at some time in your life. If you have a parent or sibling with a bicuspid valve, it increases the risk that you may have a bicuspid valve, but it can also occur if you don’t have a family history of a bicuspid aortic valve.

- Endocarditis (infection of the heart valves)

- High blood pressure

- Marfan syndrome

- Reiter syndrome (also known as reactive arthritis)

- Syphilis

- Systemic lupus erythematosus

- Trauma to the chest

Aortic insufficiency is most common in men between the ages of 30 and 60.

Risk factors for aortic regurgitation

Risk factors of aortic valve regurgitation include:

- Older age

- Certain heart conditions present at birth (congenital heart disease)

- History of infections that can affect the heart

- Certain conditions that can affect the heart, such as Marfan syndrome

- Other heart valve conditions, such as aortic valve stenosis

- High blood pressure.

Aortic regurgitation prevention

For any heart condition, see your doctor regularly so he or she can monitor you and possibly catch aortic valve regurgitation or other heart condition before it develops or in the early stages, when it’s more easily treatable. If you have been diagnosed with a leaking aortic valve (aortic valve regurgitation) or a tight aortic valve (aortic valve stenosis), you’ll probably require regular echocardiograms to be sure the aortic valve regurgitation doesn’t become severe.

Also, be aware of conditions that contribute to developing aortic valve regurgitation, including:

- Rheumatic fever. If you have a severe sore throat, see a doctor. Untreated strep throat can lead to rheumatic fever. Fortunately, strep throat is easily treated with antibiotics.

- High blood pressure. Check your blood pressure regularly. Make sure it’s well-controlled to prevent aortic regurgitation.

Aortic regurgitation signs and symptoms

Most often, aortic valve regurgitation develops gradually, and your heart compensates for the problem. You may have no signs or symptoms for years, and you may even be unaware that you have aortic valve regurgitation. Symptoms may come on slowly or suddenly.

However, as aortic valve regurgitation worsens, signs and symptoms may include:

- Fatigue and weakness, especially when you increase your activity level

- Shortness of breath with exercise or when you lie down

- Waking up short of breath some time after falling asleep

- Swelling of the feet, legs, or abdomen

- Chest pain similar to angina (rare), discomfort or tightness, often increasing during exercise

- Lightheadedness or fainting

- Uneven, rapid, racing, pounding, or fluttering pulse (arrhythmia)

- Heart murmur

- Sensations of a rapid, fluttering heartbeat (palpitations)

- Bounding pulse

- Palpitations (sensation of the heart beating)

- Weakness that is more likely to occur with activity

Aortic regurgitation signs may include:

- Heart murmur that can be heard through a stethoscope

- Very forceful beating of the heart

- Bobbing of the head in time with the heartbeat

- Hard pulses in the arms and legs

- Low diastolic blood pressure

- Signs of fluid in the lungs

Contact your doctor right away if signs and symptoms of aortic valve regurgitation develop. Sometimes the first indications of aortic valve regurgitation are those of its major complication, heart failure. See your doctor if you have fatigue, shortness of breath, and swollen ankles and feet, which are common symptoms of heart failure.

Aortic valve regurgitation complications

Aortic valve regurgitation can cause complications, including:

- Heart failure

- Infections that affect the heart, such as endocarditis

- Heart rhythm abnormalities

- Death

Aortic regurgitation diagnosis

To diagnose aortic valve regurgitation, your doctor may review your signs and symptoms, discuss your and your family’s medical history, and conduct a physical examination. Your doctor may listen to your heart with a stethoscope to determine if you have a heart murmur that may indicate an aortic valve condition. A doctor trained in heart disease (cardiologist) may evaluate you.

Physical examination reveals a characteristic high‐pitched, blowing decrescendo diastolic murmur and as soon as aortic regurgitation becomes moderate to severe—low diastolic arterial blood pressure, widened pulse pressure, and bounding pulses. Often an increase in systolic pressure also takes place. Widened pulse pressure is a useful indicator of hemodynamically significant aortic regurgitation; however, its absence does not reliably exclude severe regurgitation.

Your doctor may order several tests to diagnose your condition, and determine the cause and severity of your condition. Tests may include:

- Echocardiogram. Sound waves directed at your heart from a wandlike device (transducer) held on your chest produces video images of your heart in motion. This test can help doctors closely look at the condition of the aortic valve and the aorta. It can help doctors determine the cause and severity of your condition, and see if you have additional heart valve conditions. Doctors may also use a 3-D echocardiogram. Doctors may conduct another type of echocardiogram called a transesophageal echocardiogram to get a closer look at the aortic valve. In this test, a small transducer attached to the end of a tube is inserted down the tube leading from your mouth to your stomach (esophagus).

- Electrocardiogram (ECG). In this test, wires (electrodes) attached to pads on your skin measure the electrical activity of your heart. An ECG can detect enlarged chambers of your heart, heart disease and abnormal heart rhythms.

- Chest X-ray. This enables your doctor to determine whether your heart is enlarged — a possible indicator of aortic valve regurgitation — or whether you have an enlarged aorta. It can also help doctors determine the condition of your lungs.

- Exercise tests or stress tests. Exercise tests help doctors see whether you have signs and symptoms of aortic valve disease during physical activity, and these tests can help determine the severity of your condition. If you are unable to exercise, medications that have similar effects as exercise on your heart may be used.

- Cardiac MRI. Using a magnetic field and radio waves, this test produces detailed pictures of your heart, including the aorta and aortic valve. This test may be used to determine the severity of your condition.

- Cardiac catheterization. This test isn’t often used to diagnose aortic valve regurgitation, but it may be used if other tests aren’t able to diagnose the condition or determine its severity. Doctors may also conduct cardiac catheterization prior to valve replacement surgery to see if there are obstructions in the coronary arteries, so they can be fixed at the time of the valve surgery. In cardiac catheterization, a doctor threads a thin tube (catheter) through a blood vessel in your arm or groin to an artery in your heart and injects dye through the catheter to make the artery visible on an X-ray. This provides your doctor with a detailed picture of your heart arteries and how your heart functions. It can also measure the pressure inside the heart chambers.

Aortic regurgitation grading

A valuable and simple parameter for grading aortic regurgitation is measurement of the narrowest width of the proximal regurgitant jet (vena contracta) by color doppler 4. A jet width < 0.3 cm is highly specific for mild aortic regurgitation whereas a width > 0.6 cm is highly specific for severe aortic regurgitation 5. In very eccentric jets this measurement becomes unreliable.

Evaluation of the flow pattern in the proximal descending aorta using Pulsed wave Doppler yields additional important information 5. Holodiastolic flow reversal is specific for severe aortic regurgitation, while no or only brief diastolic flow reversal indicates mild aortic regurgitation.

Continuous-wave Doppler can be used to measure regurgitant flow velocity of the aortic regurgitation jet, which reflects the diastolic pressure gradient between the aorta and the left ventricle. The rate of deceleration and the derived pressure half‐time correspond to the rate of equalisation of these pressures. With increasing aortic regurgitation severity, aortic diastolic pressure decreases more rapidly, the late diastolic jet velocity becomes lower, and pressure half‐time becomes shorter. A pressure half‐time > 500 ms is usually consistent with mild aortic regurgitation, whereas values < 200 ms (according to some authors < 300 ms) is considered compatible with severe aortic regurgitation 5. These measurements are not always reliable, as they are affected by other causes of elevated left ventricle diastolic pressure or low aortic diastolic pressure.

A more quantitative approach using Pulsed wave Doppler is based on comparison of measurements of aortic stroke volume at the level of the left ventricular outflow tract with mitral or pulmonic stroke volume 5. Effective regurgitant orifice area (EROA) can be calculated from the regurgitant stroke volume and the regurgitant jet velocity time integral by Continuous-wave Doppler: a regurgitant volume ⩾ 60 ml and effective regurgitant orifice area (EROA) ⩾ 0.30 cm² are consistent with severe aortic regurgitation. Assessment of PISA (proximal isovelocity surface area) constitutes an alternative quantitative approach, although considerably less experience exists for assessment of aortic regurgitation than with mitral regurgitation. The PISA (proximal isovelocity surface area) approach is limited by the interposition of valve tissue when imaging from the apex. Nevertheless, minimal or no flow convergence suggests mild regurgitation, whereas a larger flow convergence is consistent with severe aortic regurgitation. Quantitation using the PISA method has also been applied for aortic regurgitation 6 and has been reported to yield regurgitant volume and, when combined with Continuous-wave Doppler measurements of jet velocity, effective regurgitant orifice area (EROA). Both quantitative methods, however, suffer from intrinsic limitations and considerable sources of error exist. Many investigators therefore recommend an integrative approach utilizing all the parameters described above to provide an accurate judgement as a basis for clinical decision making.

Table 1 summarizes the most important parameters to be considered and has been adapted from a consensus paper recently published in the US 7 and European literature.

Table 1. Grading of aortic regurgitation

| Mild | Moderate | Severe | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Specific signs for aortic regurgitation severity | Vena contracta <0.3 cm* | Intermediate values | Vena contracta >0.6 cm* | |

| Central jet width <25% of LVOT* | Intermediate values | Central jet ⩾65% of LVOT* | ||

| No or brief early diastolicflow reversal in descending aorta | Holodiastolic flow reversal in descending aorta | |||

| Flail or wide coaptation defect | ||||

| Supportive signs | PHT >500 ms | PHT <200 ms | ||

| No/minimal flow convergence* | Large flow convergence* | |||

| Moderate or greater LV enlargement | ||||

| Quantitative parameters† | ||||

| Reg volume (ml/beat) | <30 | 30–44 | 45–59 | ⩾60 |

| Reg fraction (%) | <30 | 30–39 | 40–49 | ⩾50 |

| EROA (cm2) | <0.10 | 0.10–0.19 | 0.20–0.29 | ⩾0.30 |

Footnotes: *At a Nyquist limit of 50–60 cm/s. †Quantitative parameters should be viewed with caution and only in the context of the other signs of severity because of the intrinsic limitations of quantitative measurement techniques.

Abbreviations: EROA, effective regurgitant orifice area; LV, left ventricle; LVF, left ventricular function; LVOT, left ventricular outflow tract; PHT, pressure half‐time; Reg, regurgitant.

[Source 8 ]Aortic regurgitation treatment

Treatment of aortic valve regurgitation depends on the severity of your condition, whether you’re experiencing signs and symptoms, and if your condition is getting worse.

If your symptoms are mild or you aren’t experiencing symptoms, your doctor may monitor your condition with regular follow-up appointments. Your doctor may recommend that you make healthy lifestyle changes and take medications to treat symptoms or reduce the risk of complications.

You may eventually need surgery to repair or replace the diseased aortic valve. In some cases, your doctor may recommend surgery even if you aren’t experiencing symptoms. If you’re having another heart surgery, doctors may perform aortic valve surgery at the same time. In some cases, you may need a section of the aorta (aortic root) repaired or replaced at the same time as aortic valve surgery if the aorta is enlarged.

If you have aortic valve regurgitation, consider being evaluated and treated at a medical center with a multidisciplinary team of cardiologists and other doctors and medical staff trained and experienced in evaluating and treating heart valve disease. This team can work closely with you to determine the most appropriate treatment for your condition.

Surgery to repair or replace an aortic valve is usually performed through a cut (incision) in the chest. In some cases, doctors may perform minimally invasive heart surgery, which involves the use of smaller incisions than those used in open-heart surgery.

Surgery options include:

Aortic valve repair

To repair an aortic valve, surgeons may conduct several different types of repair, including separating valve flaps (cusps) that have fused, reshaping or removing excess valve tissue so that the cusps can close tightly, or patching holes in a valve.

Doctors may use a catheter procedure to insert a plug or device to repair a leaking replacement aortic valve.

Aortic valve replacement

Aortic valve replacement is often needed to treat aortic valve regurgitation. In aortic valve replacement, your surgeon removes the damaged valve and replaces it with a mechanical valve or a valve made from cow, pig or human heart tissue (biological tissue valve). Another type of biological tissue valve replacement that uses your own pulmonary valve is sometimes possible.

Biological tissue valves degenerate over time and may eventually need to be replaced. People with mechanical valves will need to take blood-thinning medications for life to prevent blood clots. Your doctor will discuss with you the benefits and risks of each type of valve and discuss which valve may be appropriate for you.

Doctors may also conduct a catheter procedure to insert a replacement valve into a failing biological tissue valve that is no longer working properly. Other procedures using catheters to repair or replace aortic valves to treat aortic valve regurgitation continue to be researched.

Lifestyle and home remedies

You’ll have regular follow-up appointments with your doctor to monitor your condition.

While lifestyle changes can’t prevent or treat your condition, your doctor might suggest that you incorporate several heart-healthy lifestyle changes into your life. These may include:

- Eating a heart-healthy diet. Eat a variety of fruits and vegetables, low-fat or fat-free dairy products, poultry, fish, and whole grains. Avoid saturated and trans fat, and excess salt and sugar.

- Maintaining a healthy weight. Aim to keep a healthy weight. If you’re overweight or obese, your doctor may recommend that you lose weight.

- Getting regular physical activity. Aim to include about 30 minutes of physical activity, such as brisk walks, into your daily fitness routine. Ask your doctor for guidance before starting to exercise, especially if you’re considering competitive sports.

- Managing stress. Find ways to help manage your stress, such as through relaxation activities, meditation, physical activity, and spending time with family and friends.

- Avoiding tobacco. If you smoke, quit. Ask your doctor about resources to help you quit smoking. Joining a support group may be helpful.

- Controlling high blood pressure. If you’re taking blood pressure medication, ensure you take it as your doctor has prescribed.

For women with aortic valve regurgitation, it’s important to talk with your doctor before you become pregnant. Your doctor can discuss with you which medications you can safely take, and whether you may need a procedure to treat your valve condition prior to pregnancy.

You’ll likely require close monitoring by your doctor during pregnancy. Doctors may recommend that women with severe valve conditions avoid pregnancy to avoid the risk of complications.

Aortic regurgitation prognosis

Surgery can cure aortic insufficiency and relieve symptoms, unless you develop heart failure or other complications. People with angina or congestive heart failure due to aortic regurgitation do poorly without treatment.

- Wenn P, Zeltser R. Aortic Valve Disease. [Updated 2019 Jun 2]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2019 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK542205[↩][↩]

- Akinseye OA, Pathak A, Ibebuogu UN. Aortic Valve Regurgitation: A Comprehensive Review. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2018 Aug;43(8):315-334.[↩]

- Osnabrugge RL, Mylotte D, Head SJ, Van Mieghem NM, Nkomo VT, LeReun CM, Bogers AJ, Piazza N, Kappetein AP. Aortic stenosis in the elderly: disease prevalence and number of candidates for transcatheter aortic valve replacement: a meta-analysis and modeling study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013 Sep 10;62(11):1002-12.[↩]

- Tribouilloy C M, Enriquez‐Sarano M, Bailey K R. et al Assessment of severity of aortic regurgitation using the width of the vena contracta: a clinical color Doppler imaging study. Circulation 2000102558–564[↩]

- Zoghbi W A, Enriquez‐Sarano M, Foster E. et al Recommendations for evaluation of the severity of native valvular regurgitation with two‐dimensional and Doppler echocardiography. J Am Soc 200316777–802.Guideline recommending the use of the various echo‐Doppler parameters for grading AR severity.[↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Tribouilloy C M, Enriquez‐Sarano M, Fett S L. et al Application of the proximal flow convergence method to calculate the effective regurgitant orifice area in aortic regurgitation. J Am Coll Cardiol 1998321032–1039[↩]

- Recommendations for evaluation of the severity of native valvular regurgitation with two-dimensional and Doppler echocardiography. Zoghbi WA, Enriquez-Sarano M, Foster E, Grayburn PA, Kraft CD, Levine RA, Nihoyannopoulos P, Otto CM, Quinones MA, Rakowski H, Stewart WJ, Waggoner A, Weissman NJ, American Society of Echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2003 Jul; 16(7):777-802.[↩]

- Maurer G. Aortic regurgitation. Heart. 2006;92(7):994–1000. doi:10.1136/hrt.2004.042614 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1860728[↩]