Astrovirus

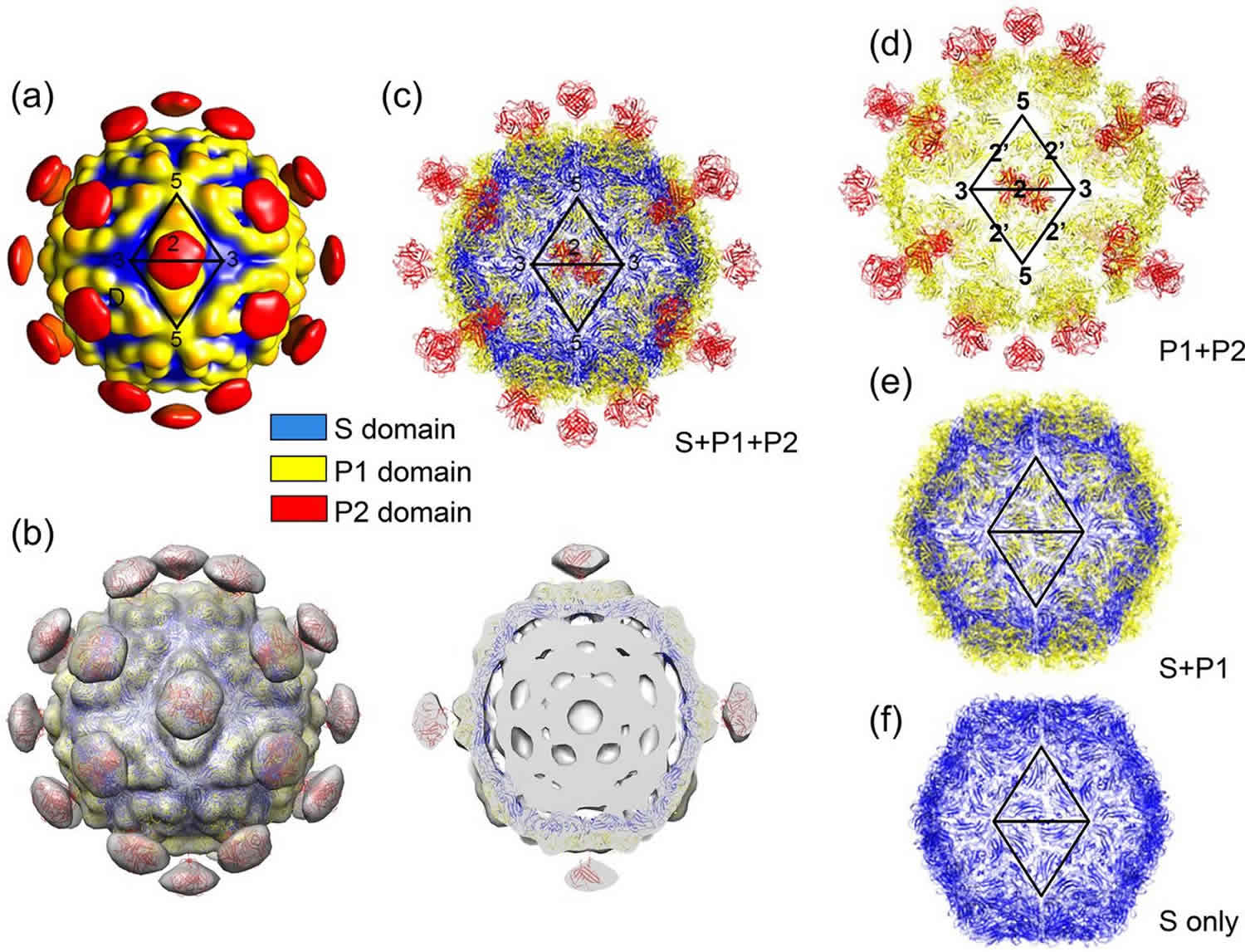

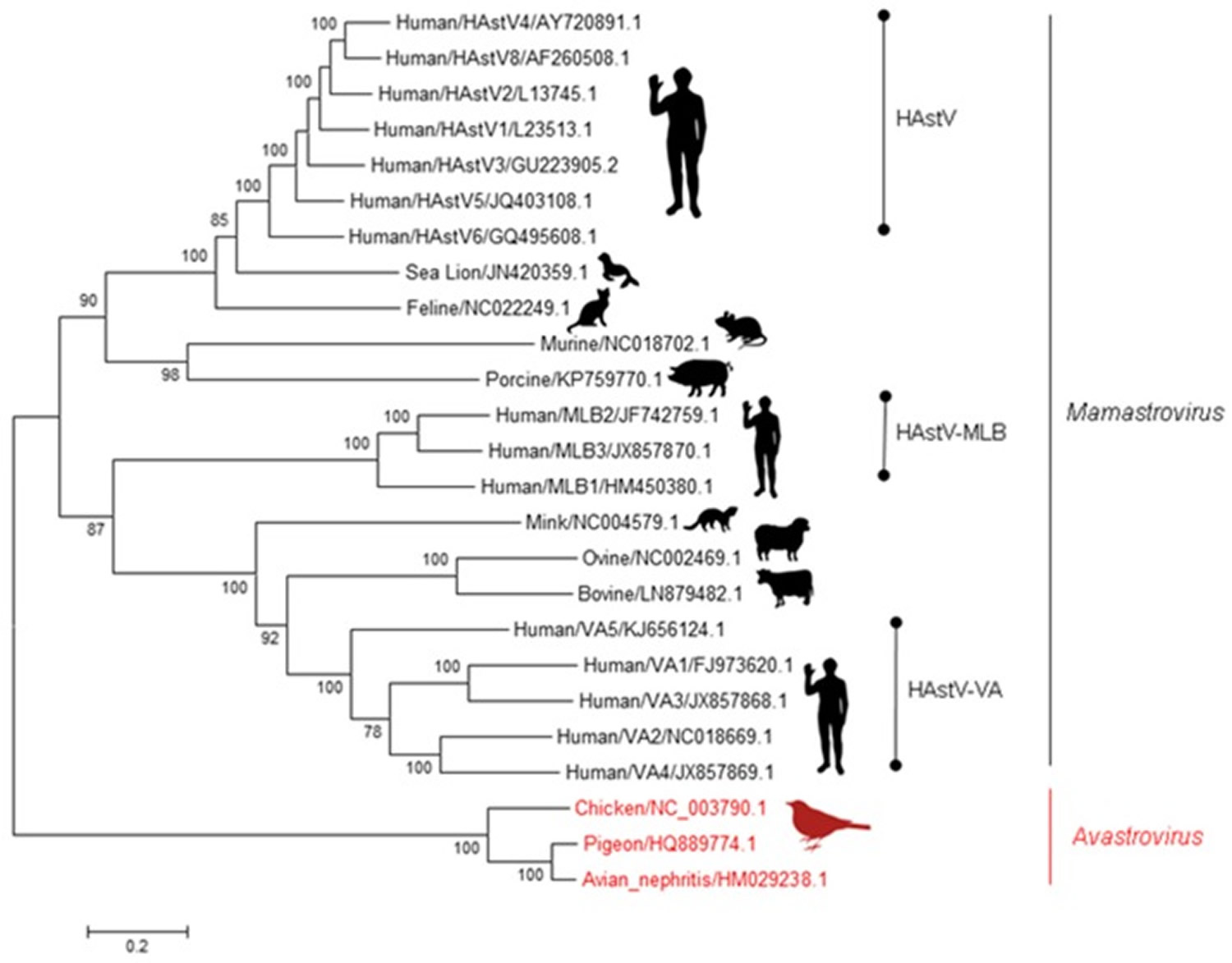

Astroviruses, family Astroviridae, are small, nonenveloped, single-stranded RNA viruses 1.. The family Astroviridae is currently divided into 2 genera: Mamastrovirus species that infect mammals, including humans, and Avastrovirus species infect poultry and other birds 2. Human astroviruses were first identified in 1975 3; until recently, only classic human astroviruses that belonged to the species Mamastrovirus 1 were recognized as human pathogens 4. Human astroviruses contribute to ≈10% of nonbacterial, sporadic gastroenteritis in children (around 90% of the population 9 years) 5, with the highest prevalence observed in community healthcare centers 6. Symptoms are generally mild, with patient hospitalization usually not required; asymptomatic carriage has been described in 2% of children 7.

Astrovirus infections were thought to be species-specific, yet turkey, chicken, and duck astroviruses share genetic features, indicating that cross-species transmission may be frequent 8. Poultry abattoir workers were three times more likely to test positive for antibodies against turkey astrovirus than people with no contact with poultry 9, and perhaps the most compelling evidence was the detection of astrovirus strains previously shown to be limited to human infections in non-human primates by real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) 10. These studies and others suggest that astroviruses can cross species barriers; however, whether these transmissions result in disease remains unclear.

Despite the high prevalence of astrovirus 11 and the advances made in the identification of novel genotypes, there is still little known about human astrovirus pathogenesis—especially among the different human astrovirus genotypes. Previous studies demonstrated that human astroviruss increase epithelial cell permeability by disrupting cellular tight junctional complexes 12. Since the intestinal tract depends on tight junctions to separate the lumen from the basal lamina, the loss of integrity increases ion, solute, and water trafficking across the compartments, reducing the ability of the intestine to reabsorb water and nutrients, leading to diarrhea. Additionally, extra-gastrointestinal astrovirus-associated disease has been reported in animals and humans 13, which could result from the increased intestinal permeability. The definite mechanisms underlying diarrhea and systemic spread remain an area of continual research; increasing our understanding of astrovirus disease will be integral for future treatment and prevention strategies. Recently, studies in both humans and animals have helped to elucidate the molecular and cellular attributes of astrovirus disease.

Figure 1. Astroviridae family

Footnote: A brief phylogenetic tree of the Astroviridae family. Phylogenetic tree with representative Avastrovirus (red) and Mamastrovirus (black) genotypes. Using full genome sequences, the evolutionary history was inferred using the Maximum Likelihood method based on the Kimura 2-parameter model. Trees were constructed using 500 bootstrapped replicates, with values above 70 shown. Branch lengths represent the number of substitutions per site.

Abbreviations: HAstV = Human astrovirus; MLB = Melbourne; VA = Virginia.

[Source 14 ]Human astrovirus infection

Within the years following the discovery of human astrovirus, eight distinct genotypes (human astrovirus type 1–8, also referred to as classical or canonical human clades) were identified, with infections caused by human astrovirus-1 shown to be the most prevalent worldwide 15. In the late 2000s, through pathogen discovery investigations of diarrheal outbreaks, two divergent human astrovirus genotypes were discovered: human astrovirus-MLB (Melbourne) clade containing at least three strains (MLB1, MLB2, MLB3) and the human astrovirus-VA/HMO (Virginia/Human-Mink-Ovine-like) clade containing at least five strains (VA1, VA2, VA3, VA4, VA5) 14. The human astrovirus-MLB and human astrovirus-VA/HMO viruses have been designated as non-canonical human genotypes. human astrovirus-MLB1 was initially discovered in pediatric stool samples from Australia 16, whereas human astrovirus-MLB2 and human astrovirus-MLB3 were discovered in India 17. The human astrovirus-VA1–VA3 viruses were first discovered in an outbreak of gastroenteritis in Virginia, USA 18; human astrovirus-VA4 in a cohort of Indian children with diarrhea 19; and human astrovirus-VA5 in a cohort in Gambia 20. The prevalence of the non-canonical viruses varies greatly according to geographic location 21, and their association with clinical disease remains somewhat of a mystery in comparison to the canonical strains.

Astrovirus infections are of clinical concern in the immunocompromised population due to their increased severity of symptoms and extra-gastrointestinal involvement 21. Human astrovirus has also been suggested to be the causative agent in encephalitis and meningitis, which was brought to light in a case report of a 15-year old boy with X-linked agammaglobulinemia by Quan et al. 22. The patient was admitted to a psychiatric ward due to cognitive decline, became comatose, and died 71 days post admission. RNA was extracted from the patient’s biopsy and postmortem samples, and sequenced and amplified with virus-specific primers, but results were negative. As an alternative approach, next-generation sequencing was utilized to identify the presence of human astrovirus in the biopsy samples. Consequently, there have now been nine cases of astrovirus-associated encephalitis and meningitis reported in predominately immunocompromised patients, although one case was in an individual without overt immunosuppression 23. Interestingly, in eight out of the nine cases, a non-canonical strain was detected in patient samples. Next-generation sequencing identified human astrovirus-VA1 in a nasopharyngeal specimen from a child with an acute respiratory infection in Tanzania, but it is unclear if human astrovirus-VA1 was responsible for the respiratory disease 24. These studies suggest that astroviruses have systemic potential, reiterating the importance of studying astrovirus pathogenesis of both canonical and non-canonical subtypes, especially since infections caused by non-canonical viruses do not appear to be rare in immunocompromised populations. In a cohort of immunocompromised pediatric oncology patients, while human astrovirus-1 was identified in 50% of samples, human astrovirus-VA2 and human astrovirus-MLB1 were also present in 21% and 13% of samples, respectively 25. However, it was noted that the PCR screening used in this study was unable to detect other members of the human astrovirus-VA and human astrovirus-MLB clades, meaning that these genotypes may be even more prevalent than reported. With improved molecular techniques for detection and diagnosis, surveillance efforts will afford a better understanding of prevalence.

There are many parallels that can be drawn between human and animal astrovirus disease, but the area remains understudied. Like humans, many of the animals infected with astrovirus exhibit diarrhea, including turkeys 26, chickens 27, calves 28, lambs 29, piglets 30, and deer 31. However, there is a subset of animals that are asymptomatic 32. Much like the human astroviruses, the impact of the asymptomatic infection on epidemiology and transmission in animal astrovirus remains unclear. Chicken astrovirus has been associated with “white chick” condition that causes a decrease in hatch-rate and an increase in chick mortality and weakness 33. Along with this, there is evidence of astrovirus-associated encephalitis and meningitis in mink and cows 13 and respiratory disease in calves 34. As with the human viruses, improved molecular techniques would lead to a better understanding of prevalence and genotype-specific astrovirus disease.

Astrovirus transmission

Astrovirus is most frequently transmitted through a fecal-oral route 35. Contaminated food, water, or fomites have been suspected in several breakouts. Adults usually do not develop gastroenteritis when deliberately given astrovirus in volunteer studies 35. In outbreaks in military barracks and childcare settings, adults may have been exposed to high doses of virus and only then have fallen ill. Astrovirus is believed to replicate in the intestinal tissue of the jejunum and ileum. Volunteer studies with healthy adults found that the average incubation period for astrovirus infection was 3 to 4 days.

Astrovirus prevention

There is no vaccine for astrovirus. Personal hygiene and decontamination of outbreak settings are important to reducing transmission and infection. Individuals can continue to shed astrovirus in their feces several days after illness resolves, and so should continue to take precautions after recovering from overt illness.

Although the survival of classic human astrovirus in drinking water is high, disinfection treatments of 2 hours with 1 mg/ml of free chlorine is quite effective 36. However, genogroup B is somewhat more resistant to chlorine disinfection than genogroup A 37, suggesting that differences in environmental persistence may exist between strains. Astrovirus survival and inactivation in food matrices have not been extensively studied, probably because only a few human astrovirus food-borne outbreaks have been described 38 and because efforts have been dedicated to the application of emerging technologies for the inactivation of other viral agents, such as norovirus and hepatitis A virus 39. Regarding disinfection of contaminated fomites, 90% alcohol has been proved useful 40. Unfortunately, no information on inactivation is yet available for nonclassic human astroviruss.

Astrovirus symptoms

Astrovirus infection causes gastroenteritis, which is characterized by the production of copious, watery diarrhea that lasts for 2 to 3 days, followed for complaints such as nausea, vomiting, fever, malaise, anorexia, headaches and abdominal pain for up to 4 days 41. However, many of the human astrovirus infections in healthy children and adults tend to be asymptomatic 42. The consequence of these asymptomatic cases on the epidemiology and transmission of astrovirus remain unclear. Further research is needed to understand the clinical disease associated with the different human astrovirus genotypes.

Astrovirus diagnosis

Due to the lack of readily available viral testing capabilities in most clinics and emergency departments, acute viral gastroenteritis is a clinical diagnosis. Therefore, patients who appear clinically well-hydrated and who lack risk factors for severe disease do not necessarily warrant further testing. Diagnostics are used to help rule out other causes of the patient’s symptoms. Complete blood counts may reveal a mild leukocytosis in a patient with viral gastroenteritis. Other serum inflammatory markers may also show mild elevation. Patients who are suffering from significant dehydration may demonstrate hemoconcentration on complete blood count testing as well as electrolyte disturbances on chemistry panels. Dehydration may also present as acute kidney injury, evidenced by changes in the blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine on chemistry panel.

Imaging studies of the abdomen most often appear normal. CT scans may reveal mild, diffuse colonic wall thickening or other inflammatory changes of the bowel. However, there are no specific findings, and CT scanning should be performed to rule out other, more severe etiologies. Stool studies may be obtained, but readily available laboratory testing assays assess only for bacterial causes and do not diagnose specific viral causes. Patients with bloody stool, high fever, severe abdominal pain, or severe dehydration warrant stool studies as these symptoms are not consistent with simple viral gastroenteritis.

Astrovirus treatment

The treatment of astrovirus gastroenteritis is based on symptomatic support 43. The most important goal of treatment is to maintain hydration status and effectively counter fluid and electrolyte losses 44. Fluid therapy is a fundamental part of treatment. Intravenous fluids may be administered to those individuals who appear dehydrated or to those unable to tolerate oral fluids. Antiemetic medications such as ondansetron or metoclopramide may be used to assist with controlling nausea and vomiting symptoms. Patients demonstrating severe dehydration or intractable vomiting may require hospital admission for continued intravenous fluids and careful monitoring of electrolyte status. Electrolyte abnormalities may be addressed on an individual level, although often these are caused by an overall fluid volume depletion which, when corrected, will also cause electrolytes to normalize. Both saline and lactated Ringer’s solutions appear to be effective for the treatment of dehydration due to viral gastroenteritis.

Debate exists over antidiarrheal medication usage. Medications such as diphenoxylate/atropine or loperamide are not recommended in patients who are 65 or older. Younger patients may benefit from antimotility medications 45. However, some feel that if a patient can maintain a well-hydrated status, antidiarrheal treatment should not be initiated. For oral rehydration, some studies have shown that commercially available oral rehydration solutions containing electrolytes are superior to sports drinks and other forms of oral rehydration 46. However, a recent study using children with mild dehydration demonstrated no differences between children receiving oral rehydration solutions versus ad lib oral intake 47. No specific nutritional recommendations are universal for patients with viral gastroenteritis. A diet of banana, rice, apples, tea, and toast is often advised, but several studies have failed to show any significant outcome difference when compared to regular diets 48.

Most patients who present to outpatient clinics or the emergency department with acute viral gastroenteritis can be discharged home safely. Adults often benefit from antiemetic medications at home although home antiemetic medication is not recommended in young children. Patients who may benefit from hospital observation or admission are those that demonstrate signs or symptoms of dehydration, intractable vomiting, severe electrolyte disturbances, significant renal failure, severe abdominal pain, or pregnancy.

Astrovirus prognosis

Astrovirus infection is generally mild and self-limiting, rarely leading to severe dehydration, hospitalization, or death. Symptoms usually resolve on their own, although individuals may continue to shed virus in their feces for days afterward. Persistent gastroenteritis occasionally occurs.

- Bosch A, Pintó RM, Guix S. Human astroviruses. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2014;27:1048–74.[↩]

- Guix S, Bosch A, Pintó RM. Astrovirus taxonomy. In: Schultz-Cherry S, editor. Astrovirus research: essential ideas, everyday impacts, future directions. New York: Springer Science + Business Media; 2013. p. 97–119.[↩]

- Appleton H, Higgins PG. Viruses and gastroenteritis in infants. Lancet. 1975;305:1297.[↩]

- Cordey, S., Vu, D., Schibler, M., L’Huillier, A. G., Brito, F., Docquier, M.Kaiser, L. (2016). Astrovirus MLB2, a New Gastroenteric Virus Associated with Meningitis and Disseminated Infection. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 22(5), 846-853. https://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid2205.151807[↩]

- Prevalence of antibodies to astrovirus types 1 and 3 in children and adolescents in Norfolk, Virginia. Mitchell DK, Matson DO, Cubitt WD, Jackson LJ, Willcocks MM, Pickering LK, Carter MJ. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1999 Mar; 18(3):249-54.[↩]

- Finkbeiner SR, Holtz LR, Jiang Y, Rajendran P, Franz CJ, Zhao G, Human stool contains a previously unrecognized diversity of novel astroviruses. Virol J. 2009;6:161.[↩]

- Moser LA, Schultz-Cherry S. Pathogenesis of astrovirus infection. Viral Immunol. 2005;18:4–10.[↩]

- Bosch A., Pintó R.M., Guix S. Human astroviruses. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2014;27:1048–1074. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00013-14[↩]

- Meliopoulos V.A., Kayali G., Burnham A., Oshansky C.M., Thomas P.G., Gray G.C., Beck M.A., Schultz-Cherry S. Detection of antibodies against turkey astrovirus in humans. PLoS ONE. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096934[↩]

- Karlsson E.A., Small C.T., Freiden P., Feeroz M.M., Iv F.A.M., San S., Hasan M.K., Wang D., Jones-Engel L., Schultz-Cherry S. Non-human primates harbor diverse mammalian and avian astroviruses including those associated with human infections. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11:e1005225. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005225[↩]

- Matusi S., Greenburg H. Astroviruses. Fields Virol. 1996;3:811–824.[↩]

- Moser L.A., Carter M., Schultz-Cherry S. Astrovirus increases epithelial barrier permeability independently of viral replication. J. Virol. 2007;81:11937–11945. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00942-07[↩]

- Li L., Diab S., McGraw S., Barr B., Traslavina R., Higgins R., Talbot T., Blanchard P., Rimoldi G., Fahsbender E., et al. Divergent astrovirus associated with neurologic disease in cattle. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2013;19:1385–1392. doi: 10.3201/eid1909.130682[↩][↩]

- Johnson C, Hargest V, Cortez V, Meliopoulos VA, Schultz-Cherry S. Astrovirus Pathogenesis. Viruses. 2017;9(1):22. Published 2017 Jan 22. doi:10.3390/v9010022 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5294991[↩][↩]

- Grazia S.D., Martella V., Chironna M., Bonura F., Tummolo F., Calderaro A., Moschidou P., Giammanco G.M., Medici M.C. Nationwide surveillance study of human astrovirus infections in an Italian paediatric population. Epidemiol. Infect. 2013;141:524–528. doi: 10.1017/S0950268812000945[↩]

- Finkbeiner S.R., Le B.-M., Holtz L.R., Storch G.A., Wang D. Detection of Newly Described Astrovirus MLB1 in Stool Samples from Children. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2009;15:441–444. doi: 10.3201/1503.081213[↩]

- Jiang H., Holtz L.R., Bauer I., Franz C.J., Zhao G., Bodhidatt L., Shrestha S.K., Kang G., Wang D. Comparison of novel MLB-clade, VA-clade and classic human astroviruses highlights constrained evolution of the classic human astrovirus nonstructural genes. Virology. 2013;436:8–14. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2012.09.040[↩]

- Finkbeiner S.R., Li Y., Ruone S., Conrardy C., Gregoricus N., Toney D., Virgin H.W., Anderson L.J., Vinjé J., Wang D., et al. Identification of a Novel Astrovirus (Astrovirus VA1) Associated with an Outbreak of Acute Gastroenteritis. J. Virol. 2009;83:10836–10839. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00998-09[↩]

- Finkbeiner S.R., Holtz L.R., Jiang Y., Rajendran P., Franz C.J., Zhao G., Kang G., Wang D. Human stool contains a previously unrecognized diversity of novel astroviruses. Virol. J. 2009;6:161. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-6-161[↩]

- Meyer C.T., Bauer I.K., Antonio M., Adeyemi M., Saha D., Oundo J.O., Ochieng J.B., Omore R., Stine O.C., Wang D., et al. Prevalence of classic, MLB-clade and VA-clade Astroviruses in Kenya and the Gambia. Virol. J. 2015;12 doi: 10.1186/s12985-015-0299-z[↩]

- Vu D.-L., Cordey S., Brito F., Kaiser L. Novel human astroviruses: Novel human diseases? J. Clin. Virol. 2016;82:56–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2016.07.004[↩][↩]

- Quan P.-L., Wagner T.A., Briese T., Torgerson T.R., Hornig M., Tashmukhamedova A., Firth C., Palacios G., Baisre-De-Leon A., Paddock C.D., et al. Astrovirus encephalitis in boy with X-linked agammaglobulinemia. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2010;16:918–925. doi: 10.3201/eid1606.091536[↩]

- Lum S.H., Turner A., Guiver M., Bonney D., Martland T., Davies E., Newbould M., Brown J., Morfopoulou S., Breuer J., et al. An emerging opportunistic infection: Fatal astrovirus (VA1/HMO-C) encephalitis in a pediatric stem cell transplant recipient. Transpl. Infect. Dis. 2016 doi: 10.1111/tid.12607[↩]

- Cordey S., Brito F., Vu D.-L., Turin L., Kilowoko M., Kyungu E., Genton B., Zdobnov E.M., D’Acremont V., Kaiser L. Astrovirus VA1 identified by next-generation sequencing in a nasopharyngeal specimen of a febrile Tanzanian child with acute respiratory disease of unknown etiology. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2016;5:e99. doi: 10.1038/emi.2016.98[↩]

- Cortez V., Freiden P., Zhengming G., Anderson E., Hayden R., Schultz-Cherry S. Diverse astrovirus genotypes co-circulated causing persistent infection in pediatric oncology patients, 2008–2011 in Memphis, Tennessee, USA. Emerg. Infect. Dis. accepted.[↩]

- McNulty M.S., Curran W.L., McFerran J.B. Detection of astroviruses in turkey faeces by direct electron microscopy. Vet. Rec. 1980;106:561. doi: 10.1136/vr.106.26.561.[↩]

- Yamaguchi S., Imada T., Kawamura H. Characterization of a picornavirus isolated from broiler chicks. Avian Dis. 1979;23:571–581. doi: 10.2307/1589732[↩]

- Woode G.N., Bridger J.C. Isolation of small viruses resembling astroviruses and caliciviruses from acute enteritis of calves. J. Med. Microbiol. 1978;11:441–452. doi: 10.1099/00222615-11-4-441[↩]

- Snodgrass D.R., Gray E.W. Detection and transmission of 30 nm virus particles (astroviruses) in faeces of lambs with diarrhoea. Arch. Virol. 1977;55:287–291. doi: 10.1007/BF01315050[↩]

- Bridger J.C. Detection by electron microscopy of caliciviruses, astroviruses and rotavirus-like particles in the faeces of piglets with diarrhoea. Vet. Rec. 1980;107:532–533.[↩]

- Tzipori S., Menzies J.D., Gray E.W. Detection of astrovirus in the faeces of red deer. Vet. Rec. 1981;108:286. doi: 10.1136/vr.108.13.286[↩]

- Hoshino Y., Zimmer J.F., Moise N.S., Scott F.W. Detection of astroviruses in feces of a cat with diarrhea. Brief report. Arch. Virol. 1981;70:373–376. doi: 10.1007/BF01320252[↩]

- Sajewicz-Krukowska J., Pać K., Lisowska A., Pikuła A., Minta Z., Króliczewska B., Domańska-Blicharz K. Astrovirus-induced “white chicks” condition—Field observation, virus detection and preliminary characterization. Avian Pathol. 2016;45:2–12. doi: 10.1080/03079457.2015.1114173[↩]

- Ng T.F.F., Kondov N.O., Deng X., van Eenennaam A., Neibergs H.L., Delwart E. A Metagenomics and case-control study to identify Viruses Associated with bovine respiratory disease. J. Virol. 2015;89:5340–5349. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00064-15[↩]

- Astroviridae. https://web.stanford.edu/group/virus/astro/2004ambili/Astrohome.html[↩][↩]

- Abad FX, Pinto RM, Villena C, Gajardo R, Bosch A. 1997. Astrovirus survival in drinking water. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:3119–3122.[↩]

- Morsy El-Senousy W, Guix S, Abid I, Pinto RM, Bosch A. 2007. Removal of astrovirus from water and sewage treatment plants, evaluated by a competitive reverse transcription-PCR. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:164–167. doi:10.1128/AEM.01748-06.[↩]

- Le Guyader FS, Le Saux JC, Ambert-Balay K, Krol J, Serais O, Parnaudeau S, Giraudon H, Delmas G, Pommepuy M, Pothier P, Atmar RL. 2008. Aichi virus, norovirus, astrovirus, enterovirus, and rotavirus involved in clinical cases from a French oyster-related gastroenteritis outbreak. J. Clin. Microbiol. 46:4011–4017. doi:10.1128/JCM.01044-08[↩]

- Kingsley DH. 2013. High pressure processing and its application to the challenge of virus-contaminated foods. Food Environ. Virol. 5:1–12. doi:10.1007/s12560-012-9094-9.[↩]

- Kurtz JB, Lee TW, Parsons AJ. 1980. The action of alcohols on rotavirus, astrovirus and enterovirus. J. Hosp. Infect. 1:321–325. doi:10.1016/0195-6701(80)90008-0[↩]

- Mitchell D.K., Matson D.O., Cubitt W.D., Jackson L.J., Willcocks M.M., Pickering L.K., Carter M.J. Prevalence of antibodies to astrovirus types 1 and 3 in children and adolescents in Norfolk, Virginia. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 1999;18:249–254. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199903000-00008[↩]

- Méndez-Toss M., Griffin D.D., Calva J., Contreras J.F., Puerto F.I., Mota F., Guiscafré H., Cedillo R., Muñoz O., Herrera I., et al. Prevalence and Genetic Diversity of Human Astroviruses in Mexican Children with Symptomatic and Asymptomatic Infections. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2004;42:151–157. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.1.151-157.2004[↩]

- Thielman NM, Guerrant RL. Clinical practice. Acute infectious diarrhea. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004 Jan 01;350(1):38-47.[↩]

- Stuempfig ND, Seroy J. Viral Gastroenteritis. [Updated 2019 Jun 17]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2019 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK518995[↩]

- Guerrant RL, Van Gilder T, Steiner TS, Thielman NM, Slutsker L, Tauxe RV, Hennessy T, Griffin PM, DuPont H, Sack RB, Tarr P, Neill M, Nachamkin I, Reller LB, Osterholm MT, Bennish ML, Pickering LK., Infectious Diseases Society of America. Practice guidelines for the management of infectious diarrhea. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2001 Feb 01;32(3):331-51.[↩]

- King CK, Glass R, Bresee JS, Duggan C., Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Managing acute gastroenteritis among children: oral rehydration, maintenance, and nutritional therapy. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2003 Nov 21;52(RR-16):1-16.[↩]

- Freedman SB, Willan AR, Boutis K, Schuh S. Effect of Dilute Apple Juice and Preferred Fluids vs Electrolyte Maintenance Solution on Treatment Failure Among Children With Mild Gastroenteritis: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2016 May 10;315(18):1966-74.[↩]

- DuPont HL. Guidelines on acute infectious diarrhea in adults. The Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 1997 Nov;92(11):1962-75.[↩]