Atrophic rhinitis

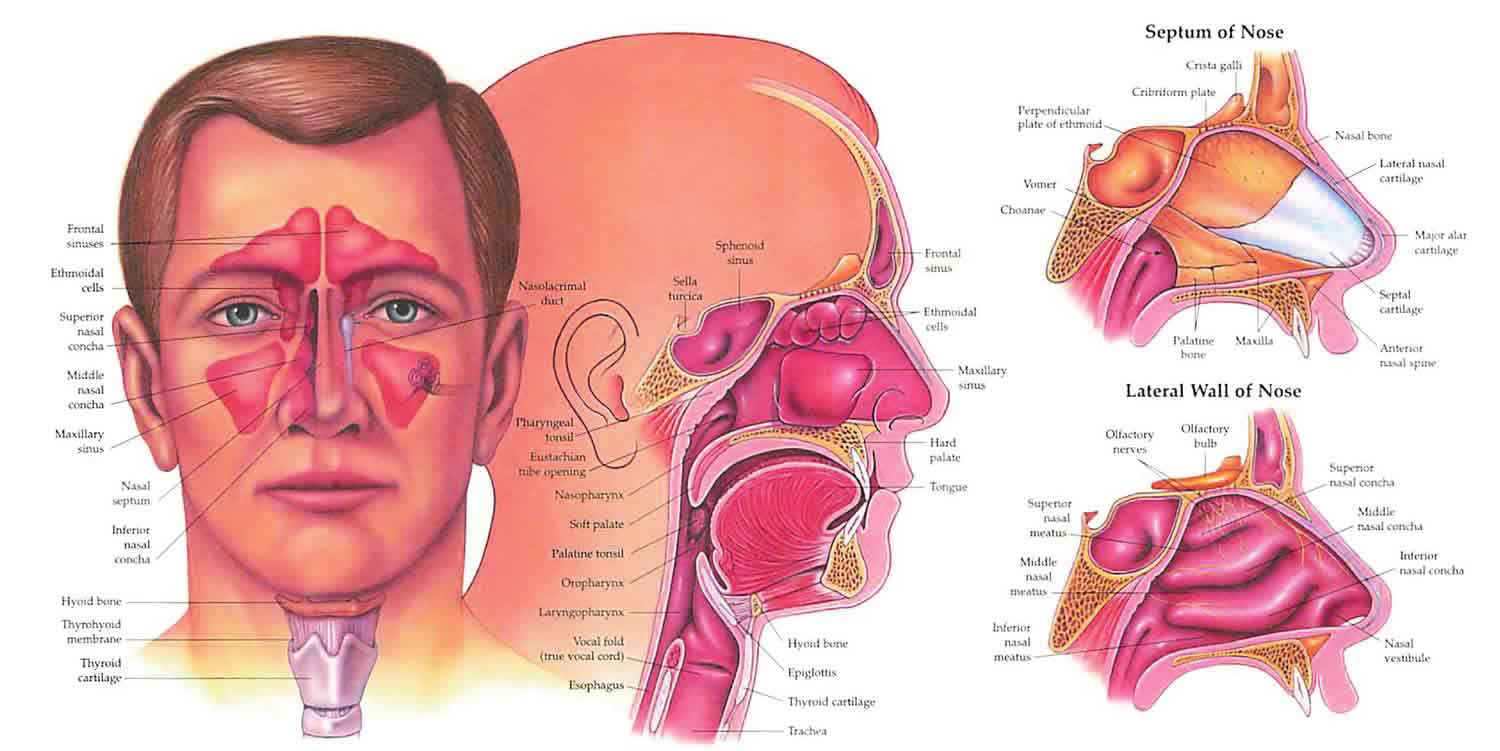

Atrophic rhinitis also called atrophic rhinosinusitis, is a chronic nasal condition with unknown cause 1. Atrophic rhinitis is characterized by the formation of thick dry crusts in a roomy nasal cavity, which has resulted from progressive wasting away or decrease in size (atrophy) of the mucous nasal lining (mucosa) and underlying bone of the turbinates. The various symptoms include strong offensive smell (fetor), crusting/nasal obstruction, nosebleeds, loss of smell (anosmia) or hallucination of disagreeable odor (cacosmia), secondary infection, maggot infestation, nasal deformity, pharyngitis, otitis media and even, rarely, extension into the brain and its membranes 1.

Atrophic rhinitis may be categorized into two forms: primary (or idiopathic) and secondary, where it is a consequence of another condition or event 2:

- Primary atrophic rhinitis is seen primarily in young people in the developing world. Primary atrophic rhinitis is associated with mucosal colonization, predominantly with Klebsiella ozaenae, as well as other organisms. The primary presenting symptom is foul-smelling nasal discharge.

- Secondary atrophic rhinitis is seen with some regularity in the developed world and occurs in patients who underwent prior sinonasal trauma, surgery, radiation therapy, or have certain inflammatory conditions (granulomatous diseases).

Atrophic rhinitis is predominantly seen in young and middle‐aged adults, especially females (6:1.5) 3. Atrophic rhinitis prevalence varies in different regions of the world. It is a common condition in tropical countries such as India, Pakistan, China, the Philippines and Malaysia, in Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Central Africa, Eastern Europe (Poland), Mediterranean areas and Latin and South America 4. Primary atrophic rhinitis has a high prevalence in the arid regions bordering the great deserts of Saudi Arabia 5. A racial preference is seen amongst Asians, Hispanics and African‐Americans. Prevalence is low in equatorial Africa 6. In those countries with a higher prevalence, primary atrophic rhinitis can affect between 0.3% and 1.0% of the population. The majority of publications on atropic rhinitis are from India, China, Poland and other regions where the condition is common 7. An environmental influence is suggested by its enhanced prevalence in rural areas (69.6%) and amongst industrial workers (43.5%) 3. Atrophic rhinitis appears to be more common in lower socio‐economic classes, poor populations and those living in conditions of poor hygiene 8. In the last four to five decades there has been a notable decline in the incidence of atrophic rhinitis in North America, Britain and some parts of Europe, however such marked decline has not been reported in Asia and Africa 1.

A wide variety of treatments have been described in the literature, however treatment is usually conservative, for example, nasal irrigation and douches; nose drops (e.g. glucose-glycerine, liquid paraffin); antibiotics and antimicrobials; vasodilators (drugs that cause dilation of blood vessels) and prostheses 1. Surgical treatment aims to decrease the size of the nasal cavities, promote regeneration of normal mucosa, increase lubrication of dry nasal mucosa and improve the vascularity (blood flow) of the nasal cavities 1.

However, there is no evidence from randomized controlled trials concerning the long‐term benefits or risks of different treatment modalities for atrophic rhinitis 1. Further high‐quality research into this chronic disease, with a longer follow‐up period, is therefore required to establish this conclusively.

Atrophic rhinitis causes

The exact cause of primary atrophic rhinitis is unknown but many factors are implicated. Primary atrophic rhinitis is seen to have a polygenic inheritance in 15% to 30% of cases, while other studies have revealed either an autosomal dominant (67%) or autosomal recessive penetrance (33%) 9. Chronic bacterial infection of the nose or sinus may be one of the causes of primary atrophic rhinitis 10. Classically Klebsiella ozaenae has been implicated 3, but other infectious agents include Coccobacillus foetidus ozaenae, Bacillus mucosus, diphtheroids, Bacillus pertussis, Haemophilus influenzae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and proteus species. It is still not clear whether these bacteria cause atrophic rhinitis or are merely secondary invaders. It may be possible that superinfection with mixed flora causes ciliostasis leading to epithelial destruction and progressive mucosal changes. A developmental cause has been suggested, which considers atrophic rhinitis to be associated with poor pneumatization of the maxillary sinuses, congenitally spacious nasal cavities, excessively patent nasal cavities in relation to shape and type of the skull and platyrrhinia 8. Nutritional deficiency, especially of iron, fat soluble vitamins and proteins, has also been suggested 11. Phospholipid deficiency 12, autonomic dysfunction leading to excessive vasoconstriction 13 or reflex sympathetic dystrophic syndrome 14, endocrinal imbalances resulting in oestrogen deficiency 15, allergy 3, immune disorders 16 and biofilm formation have also been implicated in the cause of primary atrophic rhinitis.

Secondary atrophic rhinitis, however, is known to occur as a consequence of many factors. These include local injury involving extensive accidental maxillofacial and nasal trauma/surgery notably turbinate surgery 17, recurrent acute and chronic suppurative infections of the nose/paranasal sinuses, viral exanthems in children, chronic granulomatous disorders of nose (tuberculosis, lupus vulgaris, syphilis, leprosy, rhinoscleroma, yaws, pinta) 18, typhoid fever 19 and AIDS 20. Radiation‐induced atrophic rhinitis is well reported, especially in those receiving chemotherapeutic agents and decongestants 21. Uncommon causes include occupational exposure to phosphorite and apatite dusts 22, anhydrotic ectodermal dysplasia 23, osteochondroplastic trachobronchopathy 24 and ichthyosis vulgaris 25.

Atrophic rhinitis symptoms

Atrophic rhinitis is characterized by the formation of thick dry crusts in a roomy nasal cavity, which has resulted from progressive wasting away or decrease in size (atrophy) of the mucous nasal lining (mucosa) and underlying bone of the turbinates. The various symptoms include strong offensive smell (fetor), crusting/nasal obstruction, nosebleeds, loss of smell (anosmia) or hallucination of disagreeable odor (cacosmia), secondary infection, maggot infestation, nasal deformity, pharyngitis, otitis media and even, rarely, extension into the brain and its membranes 1.

Atrophic rhinitis diagnosis

A diagnosis of atrophic rhinitis is essentially clinical and based on a triad of characteristics: foetor, greenish crusts and roomy nasal cavities. Such a full‐blown clinical picture is usually seen during later stages and the early course of disease may consist of disorder of the sense of smell (cacosmia) only, with the presence of thick nasal crusts. In the latter situation the turbinates may look normal. Two histopathological variants of atrophic rhinitis were described by Taylor and Young in 1961, depending upon the vascular involvement 26. Type 1 atrophic rhinitis is more common (50% to 80%) and is characterized by endarteritis obliterans, periarteritis and periarterial fibrosis of terminal arterioles as a result of chronic infection with round cell and plasma cell infiltration. In contrast, type 2 is less common (20% to 50%) and shows capillary vasodilation with active bone resorption. While type 1 atrophic rhinitis is likely to improve with the vasodilator effects of estrogen, type 2 atrophic rhinitis is not amenable to such therapy. It is important to exclude primary chronic sinus suppuration, suppurating adenoidal disease in adolescents, and neglected foreign body/rhinoliths in unilateral cases before diagnosing primary atrophic rhinitis. Similarly, general and systemic examination should thoroughly evaluate the possibilities of atrophic rhinitis secondary to tuberculosis, leprosy, scleroma and syphilis. Investigations, including haematological work‐up, radiological assessments and biopsy 8, mainly aim to exclude secondary causes of atrophic rhinitis and other granulomatous conditions. Apart from haemoglobin estimation (anemia), total leucocyte count or differential leucocyte count and general blood picture may show leucocytosis (infection) or a microcytic hypochromic picture (iron deficiency anemia), raised erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) (tuberculosis and granulomatous infection) and blood sugar (diabetes), which are important considerations in diagnosis. Serum protein and plasma vitamin level estimations are necessary to exclude malnutrition. In selected suspicious cases, autoimmune assays for immunological study, radiology of paranasal sinuses for assessment of bony framework, venereal disease research laboratory (VDRL) test (for syphilis), chest X‐ray and Mantoux test or enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (for tuberculosis), and ear lobe puncture/smear and nasal biopsy (for leprosy ‐ morphological and bacteriological indices) may be needed. Nasal biopsies may be performed for Young and Taylor classification and for secondary atrophic rhinitis related to nasal granuloma such as lupus, leprosy, scleroma and gumma.

Atrophic rhinitis treatment

A wide variety of treatment modalities have been described in the literature. The mainstay of treatment is conservative and includes the following:

- Nasal irrigation and douches

- Glucose‐glycerine nose drops

- Liquid paraffin nose drops

- Estradiol in arachis oil

- Kemicetine anti‐ozaena solution

- Chloramphenicol or streptomycin drops

- Placental extract

- Acetylcholine with or without pilocarpine

- Antibiotics and antimicrobials

- Iron, zinc, protein and vitamin (A and D) supplements

- Vasodilators

- Prostheses

- Vaccines

Surgical treatment aims to:

- decrease the size of nasal cavities by submucosal injection and insertion of various substances and implants (type A);

- promote regeneration of normal mucosa by classical Young’s operation and its modifications 27 (type B);

- increase lubrication of dry nasal mucosa (Raghav Sharan’s operation) (type C); and

- improve the vascularity of the nasal cavities by stellate ganglion block, cervical sympathectomy, pterygopalatine fossa block and juxta‐nasal sympathectomy (type D).

Based on the evidence discussed earlier, the mainstay of surgical management for atrophic rhinitis has been Young’s operation, while conservative management has mainly focused on lubrication of the nasal mucosa and removal of crusts. However, it is to be noted that there are methodological deficiencies in these earlier studies that either limit the validity of the findings or lead to reservations in arriving at definitive conclusions.

Some interesting observations can be made regarding the single randomized controlled trial 28 in the light of the established literature. This is the first randomized controlled trial reported to date and is from the Indian subcontinent. It compared oral rifampicin with submucosal injection of placentrex. This randomized controlled trial included three groups (1: alkaline nasal douche or control group; 2: submucosal placentrex injection group; 3: oral rifampicin group) with histological, endoscopic and subjective (as per established questionnaire) outcomes measured for a 12‐week follow‐up period. They described that the group 3 patients remained asymptomatic until the end of six months after completion of therapy, however this assessment was not based on a validated subjective questionnaire as had been used at the end of the 12‐week follow‐up period. None of the secondary outcomes were reported subsequent to that 12‐week follow‐up analysis. The best outcome was seen in group 3 followed by group 2 (the average disease‐free interval being 2.7 months); while the control group I had the lowest disease cure rate with all the patients having a moderate degree of crusting at the end of 12‐week therapy. The authors 28 mention that this control group showed the least consistent result on follow‐up with “almost all symptoms” recurring within two weeks of discontinuation of therapy. It is not clear from the loose statement “almost all symptoms” which were the specific symptoms that recurred and what their severity was. Furthermore, it was interesting to note that, with respect to histological criteria only, there was a significant difference in the outcomes of group 3 versus group 1 or group 2, while no significant difference was seen in outcomes between group 2 and group 1. In terms of endoscopic objective outcomes, the behaviour of these groups was somewhat different. The effectiveness of improving endoscopic signs was significantly increased in patients in group 2 and group 3 as compared to group 1. However, on the contrary the subjective improvement scores at 12 weeks in comparison with the 2nd week showed statistically significant improvement in all three groups. Thereafter the sustained improvement was reported only in the subjective outcomes. At this point it is to be stressed again that these improvements in histological and endoscopic criteria along with subjective improvement based on the specific questionnaire were reported only until the end of the 12‐week follow‐up period. The sustained subjective improvement involving “almost all symptoms” was based more on overall subjective reporting of the patients rather than on the established symptom scoring.

The limitations of this randomized controlled trial were multifold. Firstly the sample size was small and the follow‐up period did not satisfy the inclusion criteria amongst all groups (2.7 months in group 2 and two weeks in group 1, with no long‐term consequences). Secondly a loose criteria of subjective improvement was used after the 12‐week follow‐up period in group 3 without using a validated symptom scoring. Thirdly the potential for bias was reflected by inadequate sequence generation, inadequate allocation concealment and no blinding being considered in the study. However, despite the above limitations the authors of this randomized controlled trial should be given credit for importantly comparing the disease prognosis, albeit in the short‐term, based on the modalities used. Oral rifampicin showed the most promising results with regards to objective, subjective and histopathological improvement with maximum disease‐free interval on regular follow‐up, as compared to submucosal placentrex injection.

Apart from the various treatment modalities mentioned above, many other authors have suggested the use of rifampicin, co‐trimoxazole and ciprofloxacin 29 in atrophic rhinitis, while the use of sesame oil to combat nasal dryness has been suggested by Johnsen et al 30. None of the studies have helped in establishing the ideal management protocol but have suggested a definite role of combating nasal dryness by either using lubricants or reducing evaporation from the mucosal surface. It may be possible that atrophic rhinitis, which has a multifactorial etiology, may or may not respond to a particular modality of treatment targeting one specific aetiology, thereby resulting in variable responses across studies.

Contrary to the popular belief that extensive surgery results in iatrogenic secondary atrophy, Fang 31 reported a definite improvement with endoscopic sinus surgery in a subpopulation of atrophic rhinitis, pointing towards its infectious origin.

At a 100‐year old university hospital 32 doctors have been using liquid paraffin‐based lubricants for decades without a single incidence of paraffin granuloma being reported. In extremely severe cases with complications they traditionally opt for Young’s operation. Antibiotics are considered for a longer duration only in the presence of documented chronic infection. Unfortunately, despite having a rich clinical experience, no randomized controlled trials have yet been undertaken at that institute but currently researchers are pursuing a randomized controlled trial comparing Young’s operation and nasal lubrication 32.

- Interventions for atrophic rhinitis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 15 February 2012 https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD008280.pub2[↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Atrophic rhinosinusitis. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/atrophic-rhinosinusitis[↩]

- Bunnag C, Jareoncharsri P, Tansuriyawong P, Bhothisuwan W, Chantarakul N. Characteristics of atrophic rhinitis in Thai patients at the Siriraj Hospital. Rhinology 1999;37:125‐30.[↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Lobo CJ, Hartley C, Farrington WT. Closure of the nasal vestibule in atrophic rhinitis – a new non‐surgical technique. Journal of Laryngology and Otology 1998;112:543‐6.[↩]

- Kameswaran M. Fibreoptic endoscopy in atrophic rhinitis. Journal of Laryngology and Otology 1991;105:1014‐7.[↩]

- Weir N, Golding‐Wood DG. Infective rhinitis and sinusitis. In: Mackay IS, Bull TR editor(s). Scott Brown’s Otolaryngology. 6th Edition. Oxford: Butterworth‐Heinemann, 1997:4:4,8,26‐8.[↩]

- Dutt SN, Kameswaran M. The etiology and management of atrophic rhinitis. Journal of Laryngology and Otology 2005;119:843‐52.[↩]

- Chaturvedi VN. Atrophic rhinitis and nasal miasis. In: Kameswaran S, Kameswaran M editor(s). ENT Disorders in a Tropical Environment. 2nd Edition. MERF Publications, 1999:119‐28.[↩][↩][↩]

- Amreliwala MS, Jain SKT, Raizada RM, Sinha V, Chaturvedi VN. Atrophic rhinitis: an inherited condition. Indian Journal of Clinical Practice 1993;4:43‐6.[↩]

- Artiles F, Bordes A, Conde A, Dominguez S, Ramos JL, Suarez S. Chronic atrophic rhinitis and Klebsiella ozaenae infection. Enfermedades Infecciosas y Microbiología Clínica 2000;18:299‐300.[↩]

- Zakrzewski J. On the etiology of systemic ozaena [Polish]. Otolaryngologia Polska 1993;47:452‐8.[↩]

- Sayed RH, Abou Elhamd KE, Abdel‐Kadar M, Saleem TH. Study of surfactant level in cases of primary atrophic rhinitis. Journal of Laryngology and Otology 2000;114:254‐9.[↩]

- Ruskin JL. A differential diagnosis and therapy of atrophic rhinitis and ozaena. Archives of Otolaryngology 1932;15:222‐57.[↩]

- Ghosh P. Primary atrophic rhinitis. A new hypothesis for its etiopathogenesis. Indian Journal of Otolaryngology 1987;39:7‐13.[↩]

- Zohar Y, Talmi YP, Strauss M, Finkelstein Y, Shvilli Y. Ozena revisited. Journal of Otolaryngology 1990;19:345‐9.[↩]

- Medina L, Benazzo M, Bertino G, Montecucco CM, Danesino C, Martinetti M, et al. Clinical, genetic and immunological analysis of a family affected by ozaena. European Archives of Oto‐Rhino‐Laryngology 2003;260:390‐4.[↩]

- Moore EL, Kern EB. Atrophic rhinitis: a review of 242 cases. American Journal of Rhinology 2001;15:355‐61.[↩]

- Mehta L, Kasbekar V, Apte N, Antia NH. Evolution of nasal mucosa lesions in leprosy (histological study). Leprosy in India 1981;53:11‐6.[↩]

- Singh I, Yadav SP, Wig U. Atrophic rhinitis ‐ an unusual complication of typhoid fever. Medical Journal of Australia 1992;157:287.[↩]

- Xu Q, Dong M, Wu Y. The clinical features of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) of ear, nose, throat, head and neck [Chinese]. Lin Chuang Er Bi Yan Hou Ke Za Zhi 1999;13:552‐3.[↩]

- Chen Y, Huang G, Huang Z, Wen W, Xie C. Analysis of nasal complications after radiotherapy in patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma by logistic regression (in Chinese). Lin Chuang Er Bi Yan Hou Ke Za Zhi 2003;17:461‐3.[↩]

- Mickiewicz L, Mikulski t, Kuzna‐Grygiel W, Swiech Z. Assessment of nasal mucosa in workers exposed to the prolonged effect of phosphorite and apatite dusts. Polish Journal of Occupational Medicine and Environmental Health 1993;6:277‐85.[↩]

- Sinha V, Sinha S. Anhidrotic ectodermal dysplasia presenting as atrophic rhinitis and maggots. Indian Pediatrics 2003;40:1105‐6.[↩]

- Wiatr E, Pirozynski M, Dobrzynski P. Osteochondroplastic tracheobronchopathy ‐ relations to rhinitis atrophica and iron deficiency [Polish]. Pneumonologia i Alergologia Polska 1993;61:641‐6.[↩]

- Reisser C, Enzmann H, Gunzel S, Anton‐Lamprecht I, Born IA. Ozaena and allergic rhinitis in ichthyosis vulgaris [German]. Laryngorhinootologie 1992;71:302‐6.[↩]

- Taylor M, Young A. Histopathological and histochemical studies on atrophic rhinitis. Journal of Laryngology and Otology 1961;75:574‐90.[↩]

- Kholy A, Habib O, Abdel‐Monem MH, Abu Safia S. Septal mucoperichondrial flap for closure of nostril in atrophic rhinitis. Rhinology 1998;36:202‐3.[↩]

- Jaswal A, Jana AK, Sikder B, Nandi TK, Sadhukhan SK, Das A. Novel treatment of atrophic rhinitis: early results. European Archives of Oto‐Rhino‐Laryngology 2008;265:1211‐7.[↩][↩]

- Nielsen BC, Olinder‐Nielsen A‐M, Malmborg A‐S. Successful treatment of ozena with ciprofloxacin. Rhinology 1995;33(2):57‐60.[↩]

- Johnsen J, Bratt BM, Michel BO, Glennow C, Petruson B. Pure sesame oil vs isotonic sodium chloride solution as treatment for dry nasal mucosa. Archives of Otolaryngology ‐ Head and Neck Surgery 2001;127:1353‐6.[↩]

- Fang SY, Jin YT. Application of endoscopic sinus surgery to primary atrophic rhinitis? A clinical trial. Rhinology (Utrecht) 1998;36:122‐7.[↩]

- Mishra A. Effect of surgical vs. non‐surgical management on olfactory status in primary atrophic rhinitis. Indian Council of Medical Research.[↩][↩]