Best supplements and vitamins for depression

Depression also called major depressive disorder or clinical depression, is a disorder of the brain that affects about 1 in 10 U.S. adults 1. There are a variety of causes, including genetic, biological, environmental, and psychological factors. Depression can happen at any age, but it often begins in teens and young adults. Experts estimate that some 5 percent of U.S. teens have moderate to severe major depression. Depression is much more common in women. Women can also get postpartum depression after the birth of a baby. Some people get seasonal affective disorder (SAD) in the winter. Depression is one part of bipolar disorder (also called manic depression).

The symptoms and severity of depression can vary from person to person. Your mood, thoughts, physical health, and behavior all may be affected.

If you have been experiencing some of the following signs and symptoms most of the day, nearly every day, for at least two weeks, you may be suffering from depression:

- Persistent sad, anxious, or “empty” mood

- Feelings of hopelessness, or pessimism

- Irritability

- Feeling irritable‚ easily frustrated‚ or restless (this can be a common symptom among adolescents)

- Feelings of guilt, worthlessness, or helplessness

- Loss of interest or pleasure in hobbies and activities that used to be fun

- Decreased energy or fatigue

- Moving or talking more slowly

- Feeling restless or having trouble sitting still

- Difficulty concentrating, remembering, or making decisions

- Difficulty sleeping, early-morning awakening, or oversleeping and feeling tired

- Eating more or less than usual or having no appetite and/or weight changes

- Thoughts of death or suicide, or suicide attempts

- Aches or pains, headaches, cramps, or digestive problems without a clear physical cause and/or that do not ease even with treatment

- Having trouble concentrating, remembering details, or making decisions

Not everyone who is depressed experiences every symptom. Some people experience only a few symptoms while others may experience many. To be diagnosed with depression, the symptoms must be present for at least two weeks. The severity and frequency of symptoms and how long they last will vary depending on the individual and his or her particular illness. Symptoms may also vary depending on the stage of the illness.

Two common forms of depression are:

- Major depression, which includes symptoms of depression most of the time for at least 2 weeks that typically interfere with one’s ability to work, sleep, study, and eat.

- Persistent depressive disorder (dysthymia), which often includes less severe symptoms of depression that last much longer, typically for at least 2 years. A person diagnosed with persistent depressive disorder may have episodes of major depression along with periods of less severe symptoms, but symptoms must last for two years to be considered persistent depressive disorder.

Other forms of depression include:

- Postpartum depression is much more serious than the “baby blues” (relatively mild depressive and anxiety symptoms that typically clear within two weeks after delivery) that many women experience after giving birth. Women with postpartum depression experience full-blown major depression during pregnancy or after delivery (postpartum depression). The feelings of extreme sadness, anxiety, and exhaustion that accompany postpartum depression may make it difficult for these new mothers to complete daily care activities for themselves and/or for their babies.

- Psychotic depression occurs when a person has severe depression plus some form of psychosis, such as having disturbing false fixed beliefs (delusions) or hearing or seeing upsetting things that others cannot hear or see (hallucinations). The psychotic symptoms typically have a depressive “theme,” such as delusions of guilt, poverty, or illness.

- Seasonal affective disorder (SAD) is characterized by the onset of depression during the winter months, when there is less natural sunlight. This depression generally lifts during spring and summer. Winter depression, typically accompanied by social withdrawal, increased sleep, and weight gain, predictably returns every year in seasonal affective disorder.

- Bipolar disorder is different from depression, but it is included in this list is because someone with bipolar disorder experiences episodes of extremely low moods that meet the criteria for major depression (called “bipolar depression”). But a person with bipolar disorder also experiences extreme high – euphoric or irritable – moods called “mania” or a less severe form called “hypomania.”

Examples of other types of depressive disorders newly added to the diagnostic classification of DSM-5 include disruptive mood dysregulation disorder (diagnosed in children and adolescents) and premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD).

Depression is usually treated with medications (antidepressants), psychotherapy or a combination of the two. If these treatments do not reduce symptoms, electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) and other brain stimulation therapies may be options to explore. DO NOT try to treat moderate or severe depression on your own.

Some people might consider supplements and vitamins such as St. John’s wort, S-Adenosyl-L-methionine (SAMe), vitamin D, vitamin B6, vitamin B12, folate (vitamin B9) and omega 3 (fish oil) for depression.

Examples of supplements that are sometimes used for depression include:

- St. John’s wort. Although this herbal supplement isn’t approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat depression in the U.S., it may be helpful for mild or moderate depression. St. John’s wort has been studied extensively for depression. Most studies show it works as well as antidepressants for mild-to-moderate depression. It has fewer side effects than most antidepressants. It may take 4 to 6 weeks before you see any improvement. St. John’s wort interacts with a large number of medications, including birth control pills, so check with your doctor if you are taking prescription medications. DO NOT use St. John’s wort to treat severe depression. But if you choose to use it, be careful — St. John’s wort can interfere with a number of medications, such as heart drugs, blood-thinning drugs, birth control pills, chemotherapy, HIV/AIDS medications and drugs to prevent organ rejection after a transplant. Also, avoid taking St. John’s wort while taking antidepressants because the combination can cause serious side effects.

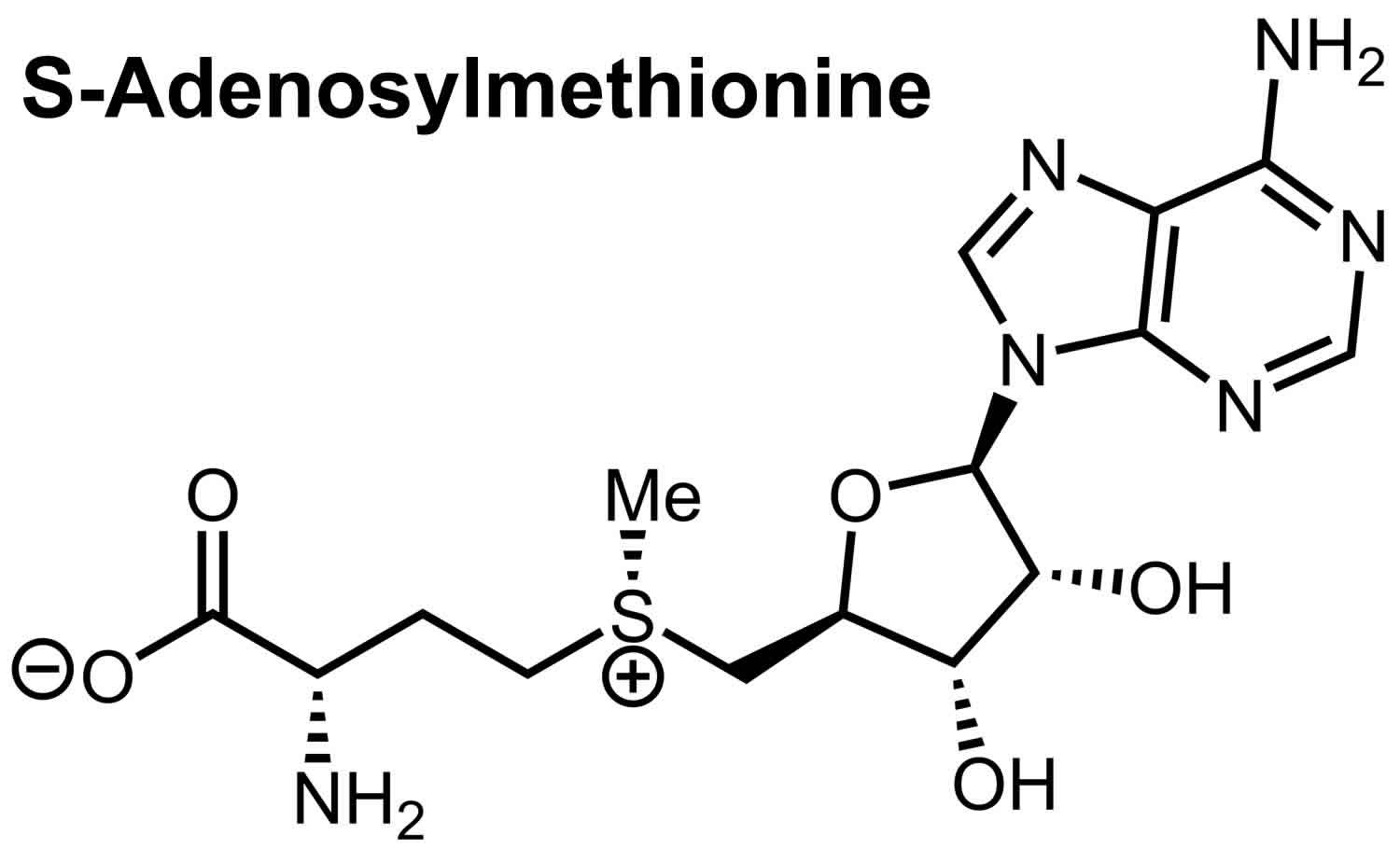

- SAMe is short for S-adenosylmethionine. Pronounced “sam-E,” this dietary supplement is a synthetic form of a chemical that occurs naturally in your body. SAMe (s-adenosyl-L-methionine) is a substance your body makes that may raise levels of the brain chemical dopamine. SAMe isn’t approved by the FDA to treat depression in the U.S. It may be helpful, but more research is needed. SAM-e has been studied for depression, but results are mixed and not all of the studies have been of good quality. Some of the studies suggest SAM-e can help relieve mild-to-moderate depression and may work faster than prescription antidepressants. If you are taking other medications for depression, talk to your doctor before taking SAMe because it may interact with them. SAM-e may trigger mania in people with bipolar disorder.

- Omega-3 fatty acids (a combination of eicosapentaenoic acid [EPA] and docosahexaenoic acid [DHA]). These healthy fats are found in cold-water fish, flaxseed, flax oil, walnuts and some other foods. Omega-3 supplements are being studied as a possible treatment for depression. Omega-3 fatty acids may help relieve symptoms of depression, but evidence is mixed. While considered generally safe, in high doses, omega-3 supplements may interact with other medications. Although eating foods with omega-3 fatty acids appears to have heart-healthy benefits, more research is needed to determine if it has an effect on preventing or improving depression. Some studies suggest that fish oil, when taken with prescription antidepressants, works better than antidepressants alone. However, a review of several studies did not find any benefit. Preliminary studies suggest that one of the omega-3 fatty acids in fish oil called EPA helps relieve depression when taken with an antidepressant. Fish oil taken in high doses may increase the risk of bleeding. DO NOT take it if you also take blood thinners, such as warfarin (Coumadin), clopidogrel (Plavix), or daily aspirin.

- Saffron (Crocus satvius). Saffron extract may improve symptoms of depression, but more study is needed. One preliminary study found that it worked as well as Prozac, while another found that it worked as well as a low dose of Tofranil. Saffron can be dangerous or even life-threatening at high doses or when taken for a long time, so DO NOT take it without your doctor’s supervision. Pregnant women and people with bipolar disorder should not take saffron supplements. High doses can cause significant side effects.

- Ginkgo (Ginkgo biloba) standardized extract, 40 to 80 mg, 3 times daily, for depression. A few studies looking at gingko for treating memory problems in older adults seemed to show that it also improved symptoms of depression. One laboratory study found that gingko, when given to older rats, increased the number of serotonin-binding sites in their brains. It did not affect younger rats, so researchers thought that it might relieve depression in older adults by helping their brains respond better to serotonin. More research is needed. Gingko may increase the risk of bleeding, especially if you also take blood thinners such as warfarin (Coumadin), clopidogrel (Plavix), or aspirin. Ask your doctor before taking gingko.

- 5-HTP also known as 5-hydroxytryptophan, is a precursor to serotonin, meaning your body changes it to serotonin (5-HT). Serotonin is commonly known as a ‘happiness hormone’ 2. Surprisingly, a decrease in serotonin (5-HT) in the brain, measured by concentrations of serotonin metabolite 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA) in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), have not been found characteristic of depression itself, but rather of impulsivity 3, suicidality and a tendency to violence 4. Serotonin exerts its action via the serotonin-1A (5-HT1A) receptor which has been reported to play a role in both prognosis and diagnosis of depression 5 as reduced serotonin-1A (5-HT1A) receptor binding is associated with depression 6. Additionally, increased autoimmune responses to serotonin were found to correlate with successive depressive episodes 7. Serotonin-2A (5-HT2A) receptor can be found at blood platelets. The density of platelet serotonin-2A (5-HT2A) receptor tends to increase in patients with depression. However, it has been found to correlate more closely with suicidality than depression per se 8. Increased serotonin-2A (5-HT2A) receptor density could potentially serve as a marker of suicide risk (state marker of depression). 5-HTP may play a role in improving serotonin levels in your brain, a chemical that affects mood. Early studies suggest it may work like antidepressant drugs, but evidence is only preliminary and more research is needed. There is a safety concern that using 5-HTP may cause a severe neurological condition, but the link is not clear. In rare cases, contaminated 5-HTP was linked to a potentially fatal condition called eosinophilia-myalgia syndrome. Another safety concern is that 5-HTP could increase the risk of serotonin syndrome — a serious side effect — if taken with certain prescription antidepressants. Taking 5-HTP with other antidepressants can cause serotonin levels in the brain to rise to dangerous levels, a condition called serotonin syndrome. You should not take 5-HTP without your doctor’s supervision.

- Vitamin D. Vitamin D can be considered a neurosteroid, with vitamin D receptors being identified in areas involved with depression, such as the prefrontal cortex, hypothalamus, and substantia nigra 9. Vitamin D has been revealed to increase the expression of genes encoding for tyrosine hydroxylase (precursor of dopamine and norepinephrine) 9. Furthermore, a major dopamine metabolite in the striatum and accumbens has been found in methamphetamine-treated animals administered vitamin D 10. Recently, many studies have examined the relationship between vitamin D and depression symptoms, especially given the complexity of treating depression and the high prevalence of vitamin D deficiency. A systematic review summarizing the evidence from observational studies concluded that vitamin D deficiency is positively associated with depression in adults 11. However, based on these observations, it is not possible to conclude that there is a causal relationship between vitamin D and depression due to potential confounders including age, dietary intake, time spent outdoors, physical activity, smoking, alcohol use, etc 12. Many randomized controlled trials of vitamin D supplementation in depression have been reported, but their findings have been inconsistent. Although some randomized controlled trials indicate a promising effect of vitamin D supplementation on depression symptoms 13, 14, others show no such effect 15, 16.

- Vitamin B6 is a generic name for six compounds (vitamers) with vitamin B6 activity: pyridoxine, pyridoxal and pyridoxamine, which contains an amino group and their respective 5’-phosphate esters. Pyridoxal 5’ phosphate (PLP) and pyridoxamine 5’ phosphate (PMP) are the active coenzyme forms of vitamin B6 17. Vitamin B6 has been used for women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder. A few studies suggest that vitamin B6 may help relieve depression that occurs with premenstrual syndrome, although the evidence is mixed. The studies used high doses, which require a doctor’s supervision. Other studies suggest that B6 may also help with other types of depression. More research is needed.

- Studies have found that some people with depression may have low levels of folic acid, vitamin B12, or vitamin D. If you have depression, you may want to ask your doctor to check your levels. So far there is no proof that taking any of these vitamins helps relieve depression. But one study suggested that women who took folic acid supplements along with Prozac did better than those who took only Prozac.

Nutritional and dietary products aren’t monitored by the FDA the same way medications are. You can’t always be certain of what you’re getting and whether it’s safe. Also, because some herbal and dietary supplements can interfere with prescription medications or cause dangerous interactions, talk to your doctor or pharmacist before taking any supplements.

Moreover, no two people are affected the same way by depression and there is no “one-size-fits-all” for treatment. It may take some trial and error to find the treatment that works best for you.

Many people with depression benefit by making lifestyle changes, such as getting more exercise, cutting down on alcohol, giving up smoking and eating healthily.

Here are other tips that may help you or a loved one during treatment for depression:

- Try to be active and exercise. Just 30 minutes a day of walking can boost mood.

- Try to maintain a regular bedtime and wake-up time.

- Avoid using alcohol, nicotine, or drugs, including medications not prescribed for you.

- Eat regular, healthy meals.

- Set realistic goals for yourself.

- Try to spend time with other people and talk with people you trust about how you are feeling.

- Try not to isolate yourself, and let others help you.

- Expect your mood to improve gradually, not immediately.

- Do what you can as you can. Decide what must get done and what can wait.

- Postpone important decisions, such as getting married or divorced, or changing jobs until you feel better. Discuss decisions with others who know you well and have a more objective view of your situation.

- Continue to educate yourself about depression.

If someone you know is showing one or more of the following behaviors, he or she may be thinking about suicide. Don’t ignore these warning signs. Get help immediately.

- Talking about wanting to die or to kill oneself

- Looking for a way to kill oneself

- Talking about feeling hopeless or having no reason to live

- Talking about feeling trapped or in unbearable pain

- Talking about being a burden to others

- Increasing the use of alcohol or drugs

- Acting anxious or agitated; behaving recklessly

- Sleeping too little or too much

- Withdrawing or feeling isolated

- Showing rage or talking about seeking revenge

- Displaying extreme mood swings

Get Help

If you or someone you know needs help, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255. Trained crisis workers are available to talk 24 hours a day, 7 days a week.

If you think someone is in immediate danger, do not leave him or her alone—stay there and call your local emergency number.

If a loved one or friend is in danger of attempting suicide or has made an attempt:

- Make sure someone stays with that person

- Call your local emergency number immediately

- Or, if you can do so safely, take the person to the nearest hospital emergency room

- Call a suicide hotline number.

- In the U.S., call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 800-273-8255. Use that same number and press “1” to reach the Veterans Crisis Line. Or call the National Hopeline Network at 1-800-784-2433

- In the UK and Ireland – call the Samaritans at 116-123

- In Australia – call Lifeline Australia at 13-11-14

- In other countries – Visit International Association for Suicide Prevention at http://www.iasp.info/resources/Crisis_Centres or Suicide.org to find a helpline in your country at http://www.suicide.org/international-suicide-hotlines.html.

Never ignore comments or concerns about suicide. Always take action to get help!

- National Mental Health Association (NMHA) 18

NMHA works to improve the mental health of all Americans through advocacy, education, research, and service 18 or go here http://www.mentalhealthamerica.net/.

- American Foundation for Suicide Prevention 19

This group is dedicated to advancing the knowledge of suicide and the ability to prevent it 19 or go here https://afsp.org/. - National Suicide Prevention Lifeline 20

National Suicide Prevention Lifeline can help prevent suicide, you can call them at 1-800-273-8255. The Lifeline provides 24/7, free and confidential support for people in distress, prevention and crisis resources for you or your loved ones, and best practices for professionals 20 or go here https://suicidepreventionlifeline.org/. - Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance 21

The Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance (DBSA) provides hope, help, support, and education to improve the lives of people who have mood disorders and manic-depressive illnesses 21 or go here http://www.dbsalliance.org

- National Alliance on Mentally Illness 22

National Alliance on Mentally Illness offers resources and help for those with a mental illness 22 or go here http://www.nami.org.

- National Institute of Mental Health 23

NIMH offers information about the symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment of mental illnesses, and supports research to help those with mental illness 23 or go here https://www.nimh.nih.gov/index.shtml.

- National Strategy for Suicide Prevention 24

National Strategy for Suicide Prevention provides information, a listing of events, and publications on suicide prevention 24 or go here http://www.mentalhealth.org/what-to-look-for/suicidal-behavior.

- National Association of Anorexia Nervosa and Associated Disorders 25

National Association of Anorexia Nervosa and Associated Disorders is a national nonprofit organization for people with eating disorders and their families. In addition to its hotline counseling, National Association of Anorexia Nervosa and Associated Disorders operates an international network of support groups and offers referrals to health care professionals who treat eating disorders 25 or go here http://www.anad.org/.

Folate (vitamin B9)

Folate also known as vitamin B9, is a water-soluble B-vitamin that is naturally present in many foods. Your body needs folate to make DNA and other genetic material. Your body also needs folate for your cells to divide and for metabolism of amino acids 26. A form of folate, called folic acid, is used in fortified foods and most dietary supplements. Some dietary supplements also contain folate in the monoglutamyl form, 5-methyl-THF (also known as L-5- MTHF, 5-MTHF, L-methylfolate or methylfolate) 27. One of the most important folate-dependent reactions is the conversion of homocysteine to methionine in the synthesis of SAMe or S-adenosyl methionine, an important methyl donor 27. Another folate-dependent reaction, the methylation of deoxyuridylate to thymidylate in the formation of DNA, is required for proper cell division. An impairment of this reaction initiates a process that can lead to megaloblastic anemia, one of the hallmarks of folate deficiency 28. People with low blood levels of folate might be more likely to have depression. In addition, they might not respond as well to antidepressant treatment as people with normal folate levels.

Folate is naturally present in a wide variety of foods, including vegetables (especially dark green leafy vegetables), fruits and fruit juices, nuts, beans, peas, seafood, eggs, dairy products, meat, poultry, and grains (see Table 2) 28. Spinach, liver, asparagus, and brussels sprouts are among the foods with the highest folate levels.

In January 1998, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) began requiring manufacturers to add 140 mcg folic acid/100 g to enriched breads, cereals, flours, cornmeals, pastas, rice, and other grain products to reduce the risk of neural tube defects 29. Because cereals and grains are widely consumed in the United States, these products have become important contributors of folic acid to the American diet. The fortification program increased mean folic acid intakes in the United States by about 190 mcg/day 30. In April 2016, FDA approved the voluntary addition of up to 154 mcg folic acid/100 g to corn masa flour 31.

Since November 1, 1998, the Canadian government has also required the addition of 150 mcg folic acid/100 g to many grains, including enriched pasta, cornmeal, and white flour 32. Many other countries, including Costa Rica, Chile, and South Africa, have also established mandatory folic acid fortification programs 31.

Low vitamin B9 (Folate) status has been linked to depression and poor response to antidepressants in some, but not all, studies 27. The possible mechanisms are unclear but might be related to folate’s role in methylation reactions in the brain, neurotransmitter synthesis, and homocysteine metabolism 33. However, secondary factors linked to depression, such as unhealthy eating patterns and alcohol use disorder, might also contribute to the observed association between low folate status and depression 34.

In a population study of 2,948 people aged 15 to 39 years in the United States, serum and red blood cell folate concentrations were significantly lower in individuals with major depression than in those who had never been depressed 34. An analysis of 2005-2006 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data found that higher serum concentrations of folate were associated with a lower prevalence of depression in 2,791 adults aged 20 or older 33. The association was statistically significant in females, but not in males. However, another analysis showed no associations between folate intakes from both food and dietary supplements and depression among 1,368 healthy Canadians aged 67–84 years 35. Results from a study of 52 men and women with major depressive disorder showed that only 1 of 14 participants with low serum folate levels responded to antidepressant treatment compared with 17 of 38 with normal folate levels 36.

A few studies have examined whether folate status affects the risk of depression during pregnancy or after childbirth. A systematic review of these studies had mixed results 37. One study included in the review among 709 women in Singapore found that compared with women with higher plasma folate concentrations (mean 40.4 nmol/L [17.8 ng/mL]) at 26–28 weeks’ gestation, those with lower plasma folate concentrations (mean 27.3 nmol/L [12.0 ng/mL]) had a significantly higher risk of depression during pregnancy but not after giving birth 38. Another study of 2,856 women in the United Kingdom found no significant associations between red blood cell folate levels or folate intakes from food and dietary supplements before or during pregnancy and postpartum depressive symptoms 39. More recently, a cohort study of 1,592 Chinese women found a lower prevalence of postpartum depression in women who took folic acid supplements for more than 6 months during pregnancy than in those who took them for less time 40.

Studies have had mixed results on whether folic acid supplementation might be a helpful adjuvant treatment (therapy that is given in addition to the primary or initial therapy to maximize its effectiveness) for depression when used with traditional antidepressant medications. In a clinical trial in the United Kingdom, 127 patients with major depression were randomly assigned to receive either 500 mcg folic acid or placebo in addition to 20 mg of fluoxetine daily for 10 weeks 41. Although the effects in men were not statistically significant, women who received fluoxetine plus folic acid had a significantly greater improvement in depressive symptoms than those who received fluoxetine plus placebo. Another clinical trial in the United Kingdom randomized 475 adults with moderate to severe depression who were taking antidepressant medications to either 5,000 mcg folic acid or placebo daily for 12 weeks in addition to their antidepressants 42. Measures of depression did not improve in participants taking folic acid compared with those taking placebo. The authors of a systematic review and meta-analysis of four trials of folic acid (<5,000 mcg/day in two trials; 5,000 mcg/day in two trials) in combination with fluoxetine or other antidepressants in patients with major depressive disorder concluded that less than 5,000 mcg/day folic acid might be beneficial as an adjunct to serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) therapy 43. The authors noted, however, that this conclusion was based on low-quality evidence. Another meta-analysis of four clinical trials found that 500–10,000 mcg folic acid per day for 6–12 weeks as an adjunctive treatment did not significantly affect measures of depression compared with placebo 44.

Other studies have examined the effects of methylfolate (5-methyl-THF) supplementation as an adjuvant treatment to antidepressants, and results suggest that it might have more promise than folic acid 45, 43. In a clinical trial in 148 adults with major depressive disorder, supplementation with 7,500 mcg/day methylfolate (5-methyl-THF) for 30 days followed by 15,000 mcg/day for another 30 days, both in conjunction with SSRI treatment, did not improve measures of depression compared with SSRI treatment plus placebo 46. However, in a subsequent trial with the same study design in 75 adults, supplementation with 15,000 mcg/day 5-methyl-THF plus SSRI treatment for the full 60 days did significantly improve depression compared with SSRI treatment plus placebo 46.

The authors of a systematic review and meta-analysis of three trials of methylfolate (<15,000 mcg/day in one trial, and 15,000 mcg/day in two trials) in combination with fluoxetine or other antidepressants, concluded that 15,000 mcg/day 5-methylfolate (5-methyl-THF) might be an effective adjunct to SSRI therapy in patients with major depressive disorder, although they noted that this conclusion was based on low-quality evidence 43. In addition, evidence-based guidelines from the British Association for Psychopharmacology 47 and the Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments 46 state that methylfolate (5-methyl-THF) might be effective as an adjunct to SSRI treatment for depressive disorders.

Additional research is needed to fully understand the association between folate status and depression. Although limited evidence suggests that supplementation with certain forms and doses of folate might be a helpful adjuvant treatment (therapy that is given in addition to the primary or initial therapy to maximize its effectiveness) for depressive disorders, more research is needed to confirm these findings. In addition, many of the doses of folate used in studies of depression exceed the Tolerable Upper Intake Level (UL) and should be taken only under medical supervision. Tolerable Upper Intake Level (UL) is the Maximum daily intake unlikely to cause adverse health effects.

The amount of folate you need depends on your age. Average daily recommended amounts are listed below in micrograms (mcg) of dietary folate equivalents (DFEs). Table 1 lists the current Recommended Dietary Allowances (RDAs) for folate as mcg of dietary folate equivalents (DFEs). The the Food and Nutrition Board at the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine developed DFEs to reflect the higher bioavailability of folic acid than that of food folate 48. At least 85% of folic acid is estimated to be bioavailable when taken with food, whereas only about 50% of folate naturally present in food is bioavailable 49. Based on these values, the Food and Nutrition Board at the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine defined dietary folate equivalent (DFE) as follows:

- 1 mcg DFE = 1 mcg food folate

- 1 mcg DFE = 0.6 mcg folic acid from fortified foods or dietary supplements consumed with foods

- 1 mcg DFE = 0.5 mcg folic acid from dietary supplements taken on an empty stomach

The measure of mcg of dietary folate equivalent (DFE) is used because your body absorbs more folic acid from fortified foods and dietary supplements than folate found naturally in foods. Compared to folate found naturally in foods, you actually need less folic acid to get recommended amounts. For example, 240 mcg of folic acid and 400 mcg of folate are both equal to 400 mcg DFE. All women and teen girls who could become pregnant should consume 400 mcg of folic acid daily from supplements, fortified foods, or both in addition to the folate they get from following a healthy eating pattern.

Factors for converting mcg DFE to mcg for supplemental folate in the form of methylfolate (5-methyl-THF) have not been formally established.

For infants from birth to 12 months, the Food and Nutrition Board established an Adequate Intake (AI) for folate that is equivalent to the mean intake of folate in healthy, breastfed infants in the United States (see Table 1).

- Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA): Average daily level of intake sufficient to meet the nutrient requirements of nearly all (97%–98%) healthy individuals; often used to plan nutritionally adequate diets for individuals.

- Adequate Intake (AI): Intake at this level is assumed to ensure nutritional adequacy; established when evidence is insufficient to develop an RDA.

Table 1. Recommended Dietary Allowances (RDAs) for Folate

| Age | Recommended Amount |

| Birth to 6 months | 65 mcg DFE |

| Infants 7–12 months | 80 mcg DFE |

| Children 1–3 years | 150 mcg DFE |

| Children 4–8 years | 200 mcg DFE |

| Children 9–13 years | 300 mcg DFE |

| Teens 14–18 years | 400 mcg DFE |

| Adults 19+ years | 400 mcg DFE |

| Pregnant teens and women | 600 mcg DFE |

| Breastfeeding teens and women | 500 mcg DFE |

Footnotes:

[Source 48 ]Folate is naturally present in:

- Beef liver

- Vegetables (especially asparagus, brussels sprouts, and dark green leafy vegetables such as spinach and mustard greens)

- Fruits and fruit juices (especially oranges and orange juice)

- Nuts, beans, and peas (such as peanuts, black-eyed peas, and kidney beans)

Folic acid is added to the following foods:

- Enriched bread, flour, cornmeal, pasta, and rice

- Fortified breakfast cereals

- Fortified corn masa flour (used to make corn tortillas and tamales)

The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s FoodData Central (https://fdc.nal.usda.gov) lists the nutrient content of many foods and provides a comprehensive list of foods containing folate arranged by nutrient content (https://ods.od.nih.gov/pubs/usdandb/Folate-Content.pdf) and by food name (https://ods.od.nih.gov/pubs/usdandb/Folate-Food.pdf).

Table 2. Folate and Folic Acid content of selected foods

| Food | Micrograms (mcg) DFE per serving | Percent DV* |

| Beef liver, braised, 3 ounces | 215 | 54 |

| Spinach, boiled, ½ cup | 131 | 33 |

| Black-eyed peas (cowpeas), boiled, ½ cup | 105 | 26 |

| Breakfast cereals, fortified with 25% of the DV† | 100 | 25 |

| Rice, white, medium-grain, cooked, ½ cup† | 90 | 22 |

| Asparagus, boiled, 4 spears | 89 | 22 |

| Brussels sprouts, frozen, boiled, ½ cup | 78 | 20 |

| Spaghetti, cooked, enriched, ½ cup† | 74 | 19 |

| Lettuce, romaine, shredded, 1 cup | 64 | 16 |

| Avocado, raw, sliced, ½ cup | 59 | 15 |

| Spinach, raw, 1 cup | 58 | 15 |

| Broccoli, chopped, frozen, cooked, ½ cup | 52 | 13 |

| Mustard greens, chopped, frozen, boiled, ½ cup | 52 | 13 |

| Bread, white, 1 slice† | 50 | 13 |

| Green peas, frozen, boiled, ½ cup | 47 | 12 |

| Kidney beans, canned, ½ cup | 46 | 12 |

| Wheat germ, 2 tablespoons | 40 | 10 |

| Tomato juice, canned, ¾ cup | 36 | 9 |

| Crab, Dungeness, 3 ounces | 36 | 9 |

| Orange juice, ¾ cup | 35 | 9 |

| Turnip greens, frozen, boiled, ½ cup | 32 | 8 |

| Peanuts, dry roasted, 1 ounce | 27 | 7 |

| Orange, fresh, 1 small | 29 | 7 |

| Papaya, raw, cubed, ½ cup | 27 | 7 |

| Banana, 1 medium | 24 | 6 |

| Yeast, baker’s, ¼ teaspoon | 23 | 6 |

| Egg, whole, hard-boiled, 1 large | 22 | 6 |

| Cantaloupe, raw, cubed, ½ cup | 17 | 4 |

| Vegetarian baked beans, canned, ½ cup | 15 | 4 |

| Fish, halibut, cooked, 3 ounces | 12 | 3 |

| Milk, 1% fat, 1 cup | 12 | 3 |

| Ground beef, 85% lean, cooked, 3 ounces | 7 | 2 |

| Chicken breast, roasted, 3 ounces | 3 | 1 |

Footnotes: * DV = Daily Value. The FDA developed DVs to help consumers compare the nutrient contents of foods and dietary supplements within the context of a total diet. The DV for folate is 400 mcg DFE for adults and children aged 4 years and older, where mcg DFE = mcg naturally occurring folate + (1.7 x mcg folic acid). The labels must list folate content in mcg DFE per serving and if folic acid is added to the product, they must also list the amount of folic acid in mcg in parentheses. The FDA does not require food labels to list folate content unless folic acid has been added to the food. Foods providing 20% or more of the DV are considered to be high sources of a nutrient, but foods providing lower percentages of the DV also contribute to a healthful diet.

† Fortified with folic acid as part of the folate fortification program.

[Source 50 ]Vitamin B6

Vitamin B6 is a generic name for six compounds (vitamers) with vitamin B6 activity: pyridoxine, pyridoxal and pyridoxamine, which contains an amino group and their respective 5’-phosphate esters. Pyridoxal 5’ phosphate (PLP) and pyridoxamine 5’ phosphate (PMP) are the active coenzyme forms of vitamin B6 17. Substantial proportions of the naturally occurring pyridoxine in fruits, vegetables, and grains exist in glycosylated forms that exhibit reduced bioavailability 51. Vitamin B6 is found in a wide variety of foods 51. The richest sources of vitamin B6 include fish, beef liver and other organ meats, potatoes and other starchy vegetables, and fruit (other than citrus). In the United States, adults obtain most of their dietary vitamin B6 from fortified cereals, beef, poultry, starchy vegetables, and some non-citrus fruits 52. About 75% of vitamin B6 from a mixed diet is bioavailable 53.

Vitamin B6 deficiency is uncommon in the United States; inadequate vitamin B6 status is usually associated with low concentrations of other B-complex vitamins, such as vitamin B12 and folate 17. People who don’t get enough vitamin B6 can have a range of symptoms, including anemia, itchy rashes, dermatitis with cheilosis (scaly skin on the lips and cracks at the corners of the mouth) and a swollen tongue (glossitis) 53. Other symptoms of very low vitamin B6 levels include depression, confusion, electroencephalographic abnormalities and a weak immune system. Infants who do not get enough vitamin B6 can become irritable or develop extremely sensitive hearing or seizures 17. Individuals with borderline vitamin B6 concentrations or mild deficiency might have no deficiency signs or symptoms for months or even years. In infants, vitamin B6 deficiency causes irritability, abnormally acute hearing, and convulsive seizures 17.

End-stage renal diseases, chronic renal insufficiency, and other kidney diseases can cause vitamin B6 deficiency 51. In addition, vitamin B6 deficiency can result from malabsorption syndromes, such as celiac disease, Crohn’s disease, and ulcerative colitis. Certain genetic diseases, such as homocystinuria, can also cause vitamin B6 deficiency 17. Some medications, such as antiepileptic drugs, can lead to deficiency over time.

A systematic review without meta-analysis for vitamin B-6 as treatment for depression revealed two randomized controlled trials showing no significant effects when compared with placebo 54.

The amount of vitamin B6 you need depends on your age. Average daily recommended amounts are listed below in milligrams (mg).

Table 3. Recommended Dietary Allowances (RDAs) for Vitamin B6

| Age | Recommended Amount |

| Birth to 6 months | 0.1 mg |

| Infants 7–12 months | 0.3 mg |

| Children 1–3 years | 0.5 mg |

| Children 4–8 years | 0.6 mg |

| Children 9–13 years | 1.0 mg |

| Teens 14–18 years (boys) | 1.3 mg |

| Teens 14–18 years (girls) | 1.2 mg |

| Adults 19–50 years | 1.3 mg |

| Adults 51+ years (men) | 1.7 mg |

| Adults 51+ years (women) | 1.5 mg |

| Pregnant teens and women | 1.9 mg |

| Breastfeeding teens and women | 2.0 mg |

Vitamin B6 is found naturally in many foods and is added to other foods. You can get recommended amounts of vitamin B6 by eating a variety of foods, including the following:

- Poultry, fish, and organ meats, all rich in vitamin B6.

- Potatoes and other starchy vegetables, which are some of the major sources of vitamin B6 for Americans.

- Fruit (other than citrus), which are also among the major sources of vitamin B6 for Americans.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA’s) FoodData Central (https://fdc.nal.usda.gov) lists the nutrient content of many foods and provides a comprehensive list of foods containing vitamin B6 arranged by nutrient content (https://ods.od.nih.gov/pubs/usdandb/VitaminB6-Content.pdf) and by food name (https://ods.od.nih.gov/pubs/usdandb/VitaminB6-Food.pdf).

Table 4. Vitamin B6 content of selected foods

| Food | Milligrams (mg) per serving | Percent DV* |

| Chickpeas, canned, 1 cup | 1.1 | 65 |

| Beef liver, pan fried, 3 ounces | 0.9 | 53 |

| Tuna, yellowfin, fresh, cooked, 3 ounces | 0.9 | 53 |

| Salmon, sockeye, cooked, 3 ounces | 0.6 | 35 |

| Chicken breast, roasted, 3 ounces | 0.5 | 29 |

| Breakfast cereals, fortified with 25% of the DV for vitamin B6 | 0.4 | 25 |

| Potatoes, boiled, 1 cup | 0.4 | 25 |

| Turkey, meat only, roasted, 3 ounces | 0.4 | 25 |

| Banana, 1 medium | 0.4 | 25 |

| Marinara (spaghetti) sauce, ready to serve, 1 cup | 0.4 | 25 |

| Ground beef, patty, 85% lean, broiled, 3 ounces | 0.3 | 18 |

| Waffles, plain, ready to heat, toasted, 1 waffle | 0.3 | 18 |

| Bulgur, cooked, 1 cup | 0.2 | 12 |

| Cottage cheese, 1% low-fat, 1 cup | 0.2 | 12 |

| Squash, winter, baked, ½ cup | 0.2 | 12 |

| Rice, white, long-grain, enriched, cooked, 1 cup | 0.1 | 6 |

| Nuts, mixed, dry-roasted, 1 ounce | 0.1 | 6 |

| Raisins, seedless, ½ cup | 0.1 | 6 |

| Onions, chopped, ½ cup | 0.1 | 6 |

| Spinach, frozen, chopped, boiled, ½ cup | 0.1 | 6 |

| Tofu, raw, firm, prepared with calcium sulfate, ½ cup | 0.1 | 6 |

| Watermelon, raw, 1 cup | 0.1 | 6 |

Footnote: *DV = Daily Value. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) developed DVs to help consumers compare the nutrient contents of foods and dietary supplements within the context of a total diet. The DV for vitamin B6 is 1.7 mg for adults and children age 4 years and older. FDA does not require food labels to list vitamin B6 content unless vitamin B6 has been added to the food. Foods providing 20% or more of the DV are considered to be high sources of a nutrient, but foods providing lower percentages of the DV also contribute to a healthful diet.

[Source 50 ]Vitamin D

Vitamin D also known as “calciferol”, is fat-soluble vitamin you need for good health. Vitamin D helps your body absorb calcium, one of the main building blocks for strong bones. Together with calcium, vitamin D helps protect you from developing osteoporosis, a disease that thins and weakens your bones and makes them more likely to break. Without sufficient vitamin D, bones can become thin, brittle, or misshapen. Vitamin D sufficiency prevents rickets in children and osteomalacia in adults 55. Your body needs vitamin D for other functions too. Your muscles need it to move, and your nerves need it to carry messages between your brain and your body. Your immune system also need vitamin D to fight off invading bacteria and viruses. Many genes encoding proteins that regulate cell proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis are modulated in part by vitamin D 56. Vitamin D is also involved in various brain processes, and vitamin D receptors are present on neurons and glia in areas of the brain thought to be involved in the pathophysiology of depression 11.

Vitamin D is naturally present in a few foods, added to others, and available as a dietary supplement. In foods and dietary supplements, vitamin D has two main forms, vitamin D2 (ergocalciferol) and vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol), that differ chemically only in their side-chain structures 55. Both forms are well absorbed in the small intestine. Absorption occurs by simple passive diffusion and by a mechanism that involves intestinal membrane carrier proteins 57. The concurrent presence of fat in the gut enhances vitamin D absorption, but some vitamin D is absorbed even without dietary fat. Neither aging nor obesity alters vitamin D absorption from the gut 57.

Vitamin D is also produced by your body when ultraviolet (UV) rays from sunlight strike your skin and trigger vitamin D synthesis. Vitamin D obtained from sun exposure, foods, and supplements is biologically inert and must undergo two hydroxylations in your body for activation. The first hydroxylation, which occurs in the liver, converts vitamin D to 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D], also known as “calcidiol.” The second hydroxylation occurs primarily in the kidney and forms the physiologically active 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D [1,25(OH)2D], also known as “calcitriol” 58. Many tissues have vitamin D receptors, and some convert 25(OH)D to 1,25(OH)2D.

Serum concentration of 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D] is currently the main indicator of vitamin D status. It reflects vitamin D produced endogenously and that obtained from foods and supplements 58. In serum, 25(OH)D has a fairly long circulating half-life of 15 days 58. Serum concentrations of 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D] are reported in both nanomoles per liter (nmol/L) and nanograms per milliliter (ng/mL). One nmol/L is equal to 0.4 ng/mL, and 1 ng/mL is equal to 2.5 nmol/L.

Researchers have not definitively identified serum concentrations of 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D] associated with vitamin D deficiency (e.g., rickets), adequacy for bone health, and overall health. After reviewing data on vitamin D needs, an expert committee of the Food and Nutrition Board at the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine concluded that people are at risk of vitamin D deficiency at serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D] concentrations less than 30 nmol/L (12 ng/mL; see Table 6 for definitions of “deficiency” and “inadequacy”) 58. Some people are potentially at risk of inadequacy at 30 to 50 nmol/L (12–20 ng/mL). Levels of 50 nmol/L (20 ng/mL) or more are sufficient for most people. In contrast, the Endocrine Society stated that, for clinical practice, a serum 25(OH)D concentration of more than 75 nmol/L (30 ng/mL) is necessary to maximize the effect of vitamin D on calcium, bone, and muscle metabolism 59. The Food and Nutrition Board committee also noted that serum concentrations greater than 125 nmol/L (50 ng/mL) can be associated with adverse effects (Table 6).

Optimal serum concentrations of 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D] for bone and general health have not been established because they are likely to vary by stage of life, by race and ethnicity, and with each physiological measure used 60. In addition, although 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D] levels rise in response to increased vitamin D intake, the relationship is nonlinear 61. The amount of increase varies, for example, by baseline serum levels and duration of supplementation.

Table 5. Recommended Dietary Allowances (RDAs) for Vitamin D

| Age | Male | Female | Pregnancy | Lactation |

| 0-12 months* | 10 mcg (400 IU) | 10 mcg (400 IU) | ||

| 1–13 years | 15 mcg (600 IU) | 15 mcg (600 IU) | ||

| 14–18 years | 15 mcg (600 IU) | 15 mcg (600 IU) | 15 mcg (600 IU) | 15 mcg (600 IU) |

| 19–50 years | 15 mcg (600 IU) | 15 mcg (600 IU) | 15 mcg (600 IU) | 15 mcg (600 IU) |

| 51–70 years | 15 mcg (600 IU) | 15 mcg (600 IU) | ||

| >70 years | 20 mcg (800 IU) | 20 mcg (800 IU) |

Footnotes:

Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA): Average daily level of intake sufficient to meet the nutrient requirements of nearly all (97%–98%) healthy individuals; often used to plan nutritionally adequate diets for individuals.

*Adequate Intake (AI): Intake at this level is assumed to ensure nutritional adequacy; established when evidence is insufficient to develop an RDA.

[Source 58 ]Table 6. Serum 25-Hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D] Concentrations and Health

| nmol/L** | ng/mL* | Health status |

|---|---|---|

| <30 | <12 | Associated with vitamin D deficiency, leading to rickets in infants and children and osteomalacia in adults |

| 30 to <50 | 12 to <20 | Generally considered inadequate for bone and overall health in healthy individuals |

| ≥50 | ≥20 | Generally considered adequate for bone and overall health in healthy individuals |

| >125 | >50 | Emerging evidence links potential adverse effects to such high levels, particularly >150 nmol/L (>60 ng/mL) |

Footnotes:

* Serum concentrations of 25(OH)D are reported in both nanomoles per liter (nmol/L) and nanograms per milliliter (ng/mL).

** 1 nmol/L = 0.4 ng/mL and 1 ng/mL = 2.5 nmol/L.

A systematic review and meta-analysis of 14 observational studies that included a total of 31,424 adults (mean age ranging from 27.5 to 77 years) found an association between deficient or low levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D] and depression 11. Clinical trials, however, do not support these findings. For example, a meta-analysis of 9 trials with a total of 4,923 adult participants diagnosed with depression or depressive symptoms found no significant reduction in symptoms after supplementation with vitamin D 62. The trials administered different amounts of vitamin D (ranging from 10 mcg [400 IU]/day to 1,000 mcg [40,000 IU]/week). They also had different study durations (5 days to 5 years), mean participant ages (range, 22 years to 75 years), and baseline 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D] levels; furthermore, some but not all studies administered concurrent antidepressant medications.

Three trials conducted since that meta-analysis also found no effect of vitamin D supplementation on depressive symptoms. One trial included 206 adults (mean age 52 years) who were randomized to take a bolus dose of 2,500 mcg (100,000 IU) vitamin D3 followed by 500 mcg (20,000 IU)/week or a placebo for 4 months 63. Most participants had minimal or mild depression, had a low mean baseline 25(OH) level of 33.8 nmol/L (13.5 ng/mL), and were not taking antidepressants. The second trial included 155 adults aged 60–80 years who had clinically relevant depressive symptoms, no major depressive disorder, and serum 25(OH)D levels less than 50 to 70 nmol/L (20 to 28 ng/mL) depending on the season; in addition, they were not taking antidepressants 64, 65. Participants were randomized to take either 30 mcg (1,200 IU)/day vitamin D3 or a placebo for 1 year. In the VITAL trial described above, 16,657 men and women 50 years of age and older with no history of depression and 1,696 with an increased risk of recurrent depression (that had not been medically treated for the past 2 years) were randomized to take 50 mcg (2,000 IU)/day vitamin D3 (with or without fish oil) or a placebo for a median of 5.3 years 66. The groups showed no significant differences in the incidence and recurrent rates of depression, clinically relevant depressive symptoms, or changes in mood scores.

Overall, clinical trials did not find that vitamin D supplements helped prevent or treat depressive symptoms or mild depression, especially in middle-aged to older adults who were not taking prescription antidepressants. No studies have evaluated whether vitamin D supplements may benefit individuals under medical care for clinical depression who have low or deficient 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D] levels and are taking antidepressant medication.

Table 7. Vitamin D content of selected foods

| Food | Micrograms (mcg) per serving | International Units (IU) per serving | Percent DV* |

| Cod liver oil, 1 tablespoon | 34 | 1360 | 170 |

| Trout (rainbow), farmed, cooked, 3 ounces | 16.2 | 645 | 81 |

| Salmon (sockeye), cooked, 3 ounces | 14.2 | 570 | 71 |

| Mushrooms, white, raw, sliced, exposed to UV light, ½ cup | 9.2 | 366 | 46 |

| Milk, 2% milkfat, vitamin D fortified, 1 cup | 2.9 | 120 | 15 |

| Soy, almond, and oat milks, vitamin D fortified, various brands, 1 cup | 2.5-3.6 | 100-144 | 13-18 |

| Ready-to-eat cereal, fortified with 10% of the DV for vitamin D, 1 serving | 2 | 80 | 10 |

| Sardines (Atlantic), canned in oil, drained, 2 sardines | 1.2 | 46 | 6 |

| Egg, 1 large, scrambled** | 1.1 | 44 | 6 |

| Liver, beef, braised, 3 ounces | 1 | 42 | 5 |

| Tuna fish (light), canned in water, drained, 3 ounces | 1 | 40 | 5 |

| Cheese, cheddar, 1 ounce | 0.3 | 12 | 2 |

| Mushrooms, portabella, raw, diced, ½ cup | 0.1 | 4 | 1 |

| Chicken breast, roasted, 3 ounces | 0.1 | 4 | 1 |

| Beef, ground, 90% lean, broiled, 3 ounces | 0 | 1.7 | 0 |

| Broccoli, raw, chopped, ½ cup | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Carrots, raw, chopped, ½ cup | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Almonds, dry roasted, 1 ounce | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Apple, large | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Banana, large | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Rice, brown, long-grain, cooked, 1 cup | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Whole wheat bread, 1 slice | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Lentils, boiled, ½ cup | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Sunflower seeds, roasted, ½ cup | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Edamame, shelled, cooked, ½ cup | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Footnotes:

* DV = Daily Value. The FDA developed DVs to help consumers compare the nutrient contents of foods and dietary supplements within the context of a total diet. The DV for vitamin D is 20 mcg (800 IU) for adults and children aged 4 years and older. The labels must list vitamin D content in mcg per serving and have the option of also listing the amount in IUs in parentheses. Foods providing 20% or more of the DV are considered to be high sources of a nutrient, but foods providing lower percentages of the DV also contribute to a healthful diet.

** Vitamin D is in the yolk.

[Source 67 ]Omega 3 fatty acids (fish oil)

Omega-3 fatty acids are found in foods, such as fish and flaxseed, and in dietary supplements, such as fish oil 68. The three main omega-3 fatty acids are alpha-linolenic acid (ALA), eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA). Alpha-linolenic acid (ALA) is found mainly in plant oils such as flaxseed, soybean, and canola oils 69. DHA (docosahexaenoic acid) and EPA (eicosapentaenoic acid) are present in fish, fish oils, krill oils and other seafood, but they are originally synthesized by microalgae, not by the fish. When fish consume phytoplankton that consumed microalgae, they accumulate the omega-3s in their tissues 69.

Alpha-linolenic acid (ALA) is an essential fatty acid, meaning that your body can’t make it, so you must get it from the foods and beverages you consume. Your body can convert some alpha-linolenic acid (ALA) into EPA (eicosapentaenoic acid) and then to DHA (docosahexaenoic acid), but only in very small amounts 68. Therefore, getting DHA (docosahexaenoic acid) and EPA (eicosapentaenoic acid) from foods (and dietary supplements if you take them) is the only practical way to increase levels of these omega-3 fatty acids in your body.

Omega-3s are important components of the membranes that surround each cell in your body. DHA (docosahexaenoic acid) levels are especially high in retina (eye), brain, and sperm cells. Omega-3s also provide calories to give your body energy and have many functions in your heart, blood vessels, lungs, immune system, and endocrine system (the network of hormone-producing glands).

A deficiency of omega-3s can cause rough, scaly skin and a red, swollen, itchy rash. Omega-3 deficiency is very rare in the United States. According to data from the 2011–2012 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), most children and adults in the United States consume recommended amounts of omega-3s as ALA 70. Among children and teens aged 2–19 the average daily ALA intake from foods is 1.32 g for females and 1.55 g for males. In adults aged 20 and over, the average daily ALA intake from foods is 1.59 g in females and 2.06 g in males.

Consumption of DHA and EPA from foods contributes a very small amount to total daily omega-3 intakes (about 40 mg in children and teens and about 90 mg in adults) 70. Use of dietary supplements containing omega-3s also contributes to total omega-3 intakes. Fish oil is one of the most commonly used nonvitamin/nonmineral dietary supplements by U.S. adults and children 71, 72. Data from the 2012 National Health Interview Survey indicate that 7.8% of U.S. adults and 1.1% of U.S. children use supplements containing fish oil, omega-3s, and/or DHA or EPA 71, 72. According to an analysis of 2003–2008 NHANES data, use of these supplements adds about 100 mg to mean daily ALA intakes, 10 mg to mean DHA intakes, and 20 mg to mean EPA intakes in adults 73.

A deficiency of essential fatty acids—either omega-3s or omega-6s—can cause rough, scaly skin and dermatitis 74. Plasma and tissue concentrations of DHA decrease when an omega-3 fatty acid deficiency is present. However, there are no known cut-off concentrations of DHA or EPA below which functional endpoints, such as those for visual or neural function or for immune response, are impaired.

It’s uncertain whether omega-3 fatty acid supplements are helpful for depression. Although some studies have found conflicting evidence, a high-quality 2015 Cochrane review of 26 studies that included more than 1,400 people on supplementation with omega-3 fatty acids (1,000 to 6,600 mg/day EPA, DHA, and/or other omega-3s) versus placebo in patients with major depression concluded that if there is a small-to-modest beneficial effect on depressive symptoms, but it may be too small to be meaningful 75. One additional randomized controlled trial with a very low sample size showed similar effects of omega-3 fatty acids on severity and response rates in comparison with antidepressant drug treatment 76. Other analyses have suggested that if omega-3s do have an effect, EPA may be more beneficial than DHA and that omega-3s may best be used in addition to antidepressant medication rather than in place of it 77. However, all meta-analyses were based on very low quality of evidence because of limitations of the study quality, significant heterogeneity, imprecision and a possibly high risk of publication bias. Furthermore, omega-3s have not been shown to relieve symptoms of depression that occur during pregnancy or after childbirth.

A 2016 meta-analysis of 26 studies found a 17% lower risk of depression with higher fish intake 78.

Table 8. Recommended daily intake for Omega-3s

| Age | Male | Female | Pregnancy | Lactation |

| Birth to 6 months* | 0.5 g | 0.5 g | ||

| 7–12 months* | 0.5 g | 0.5 g | ||

| 1–3 years** | 0.7 g | 0.7 g | ||

| 4–8 years** | 0.9 g | 0.9 g | ||

| 9–13 years** | 1.2 g | 1.0 g | ||

| 14–18 years** | 1.6 g | 1.1 g | 1.4 g | 1.3 g |

| 19-50 years** | 1.6 g | 1.1 g | 1.4 g | 1.3 g |

| 51+ years** | 1.6 g | 1.1 g |

Footnotes:

*As total omega-3s

**As alpha-linolenic acid (ALA)

[Source 74 ]Table 9. Omega-3 content of selected foods

| Food | Grams per serving | ||

| ALA (alpha-linolenic acid) | DHA (docosahexaenoic acid) | EPA (eicosapentaenoic acid) | |

| Flaxseed oil, 1 tbsp | 7.26 | ||

| Chia seeds, 1 ounce | 5.06 | ||

| English walnuts, 1 ounce | 2.57 | ||

| Flaxseed, whole, 1 tbsp | 2.35 | ||

| Salmon, Atlantic, farmed cooked, 3 ounces | 1.24 | 0.59 | |

| Salmon, Atlantic, wild, cooked, 3 ounces | 1.22 | 0.35 | |

| Herring, Atlantic, cooked, 3 ounces* | 0.94 | 0.77 | |

| Canola oil, 1 tbsp | 1.28 | ||

| Sardines, canned in tomato sauce, drained, 3 ounces* | 0.74 | 0.45 | |

| Mackerel, Atlantic, cooked, 3 ounces* | 0.59 | 0.43 | |

| Salmon, pink, canned, drained, 3 ounces* | 0.04 | 0.63 | 0.28 |

| Soybean oil, 1 tbsp | 0.92 | ||

| Trout, rainbow, wild, cooked, 3 ounces | 0.44 | 0.4 | |

| Black walnuts, 1 ounce | 0.76 | ||

| Mayonnaise, 1 tbsp | 0.74 | ||

| Oysters, eastern, wild, cooked, 3 ounces | 0.14 | 0.23 | 0.3 |

| Sea bass, cooked, 3 ounces* | 0.47 | 0.18 | |

| Edamame, frozen, prepared, ½ cup | 0.28 | ||

| Shrimp, cooked, 3 ounces* | 0.12 | 0.12 | |

| Refried beans, canned, vegetarian, ½ cup | 0.21 | ||

| Lobster, cooked, 3 ounces* | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.1 |

| Tuna, light, canned in water, drained, 3 ounces* | 0.17 | 0.02 | |

| Tilapia, cooked, 3 ounces* | 0.04 | 0.11 | |

| Scallops, cooked, 3 ounces* | 0.09 | 0.06 | |

| Cod, Pacific, cooked, 3 ounces* | 0.1 | 0.04 | |

| Tuna, yellowfin, cooked 3 ounces* | 0.09 | 0.01 | |

| Kidney beans, canned ½ cup | 0.1 | ||

| Baked beans, canned, vegetarian, ½ cup | 0.07 | ||

| Ground beef, 85% lean, cooked, 3 ounces** | 0.04 | ||

| Bread, whole wheat, 1 slice | 0.04 | ||

| Egg, cooked, 1 egg | 0.03 | ||

| Chicken, breast, roasted, 3 ounces | 0.02 | 0.01 | |

| Milk, low-fat (1%), 1 cup | 0.01 | ||

Footnotes:

*Except as noted, the USDA database does not specify whether fish are farmed or wild caught.

**The USDA database does not specify whether beef is grass fed or grain fed.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s FoodData Central (https://fdc.nal.usda.gov) lists the nutrient content of many foods and provides a comprehensive list of foods containing alpha-linolenic acid (ALA) arranged by nutrient content (https://ods.od.nih.gov/pubs/usdandb/ALA-Content.pdf) and by food name (https://ods.od.nih.gov/pubs/usdandb/ALA-Food.pdf), foods containing DHA (docosahexaenoic acid) arranged by nutrient content (https://ods.od.nih.gov/pubs/usdandb/DHA-Content.pdf) and by food name (https://ods.od.nih.gov/pubs/usdandb/DHA-Food.pdf), and foods containing EPA (eicosapentaenoic acid) arranged by nutrient content (https://ods.od.nih.gov/pubs/usdandb/EPA-Content.pdf) and by food name (https://ods.od.nih.gov/pubs/usdandb/EPA-Food.pdf).

[Source 67 ]St John’s Wort

St. John’s wort also known as Hypericum perforatum, Klamath weed or goat weed, is a perennial flowering shrub native to Europe and Asia and was brought to the United States by European colonists. The flowers and leaves of St. John’s wort contain active ingredients such as hyperforin. The name St. John’s wort apparently refers to John the Baptist, as the plant blooms around the time of the feast of St. John the Baptist in late June (June 24). It is also said its red pigment symbolizes the blood of St. John. The word wort is an Old English term for plant. Hypericum is derived from the Greek words hyper (above) and eikon (icon or image). Historically, St. John’s wort has been used for a variety of conditions, including kidney and lung ailments, insomnia, and depression, and to aid wound healing. Currently, St. John’s wort is promoted for depression, menopausal symptoms, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), somatic symptom disorder (a condition in which a person feels extreme, exaggerated anxiety about physical symptoms), obsessive-compulsive disorder, and other conditions. Topical use (applied to the skin) of St. John’s wort is promoted for various skin conditions, including wounds, bruises, and muscle pain.

There has been extensive research on the use of St. John’s wort for depression and on its interactions with medications. Several studies support the therapeutic benefit of St. John’s wort in treating mild to moderate depression 79, 80, 81, 76, 82. In fact, some research has shown St. John’s wort supplement to be as effective as several prescription antidepressants 81. In comparison with standard antidepressants, St. John’s wort showed comparable severity reductions, response, remission, and relapse rates 76. However, it’s unclear whether St. John’s wort is beneficial in the treatment of severe depression and for time periods longer than 12 weeks 83. While there may be public interest in St. John’s wort to treat depression, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has not approved its use as an over-the-counter or prescription medicine for depression. In research studies, taking St. John’s wort by mouth for up to 12 weeks has seemed to be safe. But because St. John’s wort interacts with many medications, it might not be safe for many people, especially those who take conventional medicines, particularly if you take any prescription drugs 84. St. John’s wort is known to affect metabolism of a number of drugs and can cause serious side effects. Combining St. John’s wort with certain antidepressants can lead to a potentially life-threatening increase of serotonin, a brain chemical targeted by antidepressants. St. John’s wort can also limit the effectiveness of many prescription medicines, including birth control pills, digoxin, some HIV drugs and cancer medications, and others 85.

St. John’s wort can also weaken the effects of many medicines, including crucially important medicines such as:

- Antidepressants

- Birth control pills

- Cyclosporine, which prevents the body from rejecting transplanted organs

- Some heart medications, including digoxin and ivabradine

- Some HIV drugs, including indinavir and nevirapine

- Some cancer medications, including irinotecan and imatinib

- Warfarin, an anticoagulant (blood thinner)

- Certain statins, including simvastatin.

Little safety information on St. John’s wort for pregnant women, during breastfeeding or in children is available, so it is especially important to talk with health experts if you are pregnant or nursing or are considering giving a dietary supplement to a child. St. John’s wort has caused birth defects in laboratory animals. Breastfeeding infants of mothers who take St. John’s wort can experience colic, drowsiness, and fussiness.

St. John’s wort may cause increased sensitivity to sunlight, especially when taken in large doses. Other side effects can include insomnia, anxiety, dry mouth, dizziness, gastrointestinal symptoms, fatigue, headache, or sexual dysfunction. Therefore, if you consider using St. John’s wort for depression, you should seek professional advise 86. Clinical studies on the use of St. John’s wort for depression have utilized liquid tinctures and standardized solid extracts (0.3% hypericin—300 mg three times a day) 87.

5 HTP

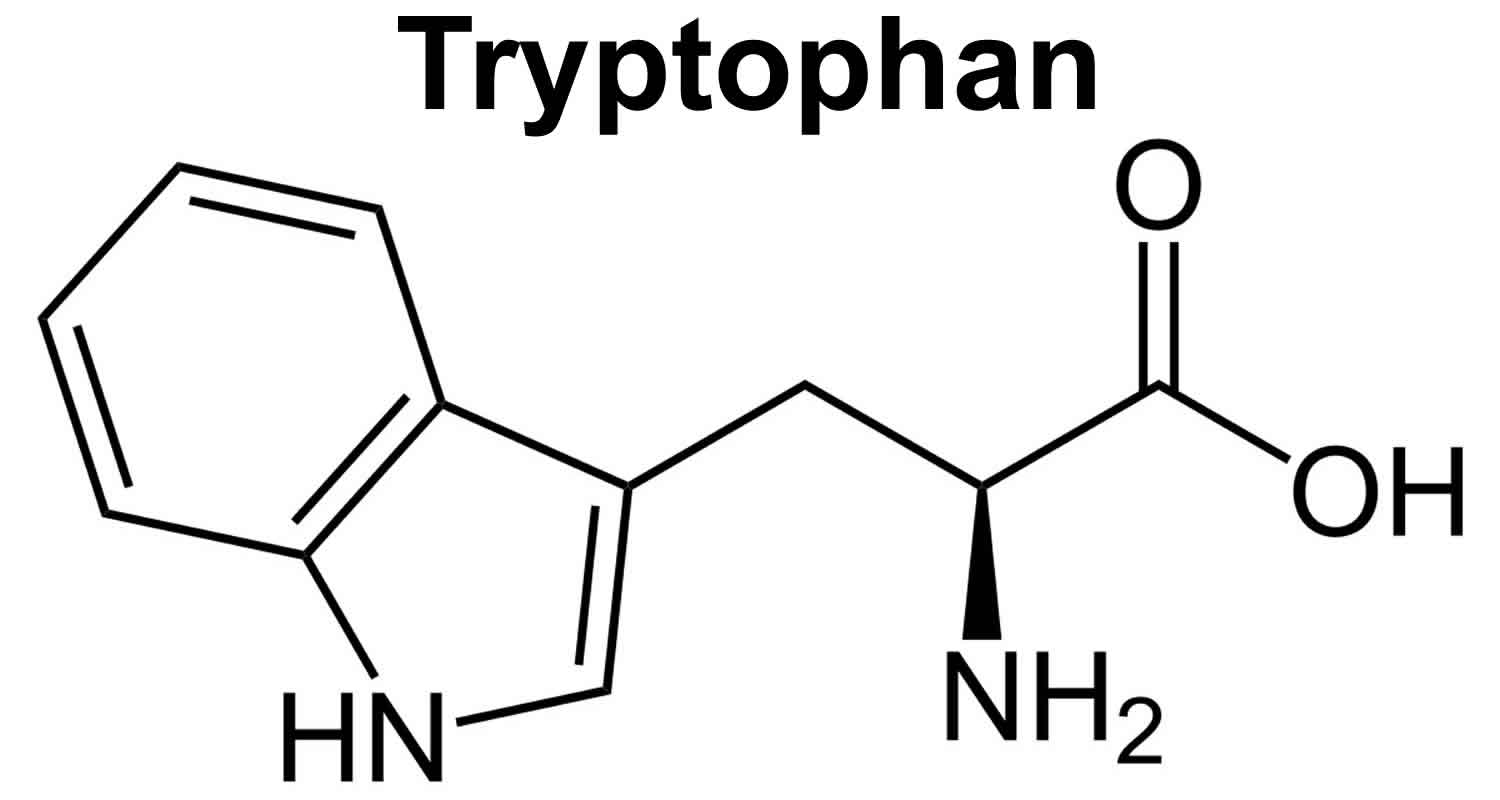

5-HTP also known as 5-hydroxytryptophan, is a chemical that your body makes from tryptophan (an essential amino acid that you get from food) 88. You can’t get 5-HTP from food. The essential amino acid tryptophan (L-tryptophan), which your body uses to make 5-HTP, can be found in turkey, chicken, milk, potatoes, pumpkin, sunflower seeds, turnip and collard greens, and seaweed. However, eating foods with tryptophan does not increase 5-HTP levels very much. After tryptophan is converted into 5-HTP, the chemical is changed into another chemical called serotonin also known as 5-hydroxytryptamine (a neurotransmitter that relays signals between brain cells). 5-HTP dietary supplements help raise serotonin levels in the brain. Since serotonin helps regulate mood and behavior, 5-HTP may have a positive effect on sleep, mood, anxiety, appetite, and pain sensation.

As a supplement, 5-HTP is commercially produced by extraction from the seeds of the African plant called Griffonia simplicifolia. In the United States 5-HTP is regulated as a food supplement. There is no U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved drug on the market containing 5-HTP as an active pharmaceutical ingredient 89. According to Jacobsen et al 89, no dosage form of 5-HTP has ever been formally developed as a drug and approved by a regulatory body for the treatment of a disease.

Therapeutic use of 5-HTP bypasses the conversion of tryptophan (L-tryptophan) into 5-HTP by the enzyme tryptophan hydrolase, which is the rate-limiting step in the synthesis of serotonin 88. Tryptophan hydrolase can be inhibited by numerous factors, including stress, insulin resistance, vitamin B6 deficiency, and insufficient magnesium 88. In addition, these same factors can increase the conversion of tryptophan to kynurenine via tryptophan oxygenase, making tryptophan unavailable for serotonin production.

Serotonin levels in the brain are highly dependent on levels of 5-HTP and L-tryptophan in the central nervous system (brain and spinal cord) 88. 5-HTP easily crosses the blood-brain barrier, not requiring the presence of a transport molecule. Tryptophan, on the other hand, requires use of a transport molecule to gain access to the central nervous system. Since it shares this transport molecule with several other amino acids, the presence of these competing amino acids can inhibit L-tryptophan transport into the brain.

5-HTP acts primarily by increasing levels of serotonin within the central nervous system. Other neurotransmitters and central nervous system chemicals, such as melatonin, dopamine, norepinephrine, and beta-endorphin have also been shown to increase following oral administration of 5-HTP 90.

The use of the essential amino acid L-tryptophan as a dietary supplement was discontinued in 1989 due to an outbreak of eosinophilia-myalgia syndrome (EMS) that was traced to a contaminated synthetic L-tryptophan from a single manufacturer. In 1989, the presence of a contaminant called Peak X was found in tryptophan supplements. Researchers believed that an outbreak of eosinophilic myalgia syndrome (a potentially fatal disorder that affects the skin, blood, muscles, and organs) could be traced to the contaminated tryptophan, and the FDA pulled all tryptophan supplements off the market. Since then, Peak X was also found in some 5-HTP supplements, and there have been a few reports of eosinophilic myalgia syndrome associated with taking 5-HTP. However, the level of Peak X in 5-HTP was not high enough to cause any symptoms, unless very high doses of 5-HTP were taken. Because of this concern, however, you should talk to your health care provider before taking 5-HTP, and make sure you get the supplement from a reliable manufacturer.

The primary concern regarding 5-HTP is the possibility of an eosinophilia-myalgia syndrome (EMS) similar to the illness linked to contaminated L-tryptophan. The contamination identified in certain batches of L-tryptophan has been related to production methods using bacterial fermentation and subsequent inadequate filtration. This is unlikely to occur with 5-HTP, since it is produced by extraction from plant sources. Two cases of eosinophilia-myalgia syndrome-like symptoms have been described in patients taking 5-HTP. One case reported in 1980 involved the use of very high doses (1400 mg daily) 91. Because contamination of L-tryptophan was not identified as a factor in eosinophilia-myalgia syndrome (EMS) until 1990, the product consumed by this patient was not tested for contamination. The second case involved a mother and two children who were confirmed to have taken contaminated 5-HTP 92.

5-HTP has since become a popular dietary supplement in lieu of the removal of L-tryptophan from the market. Because of its chemical and biochemical relationship to L-tryptophan, 5-HTP has been under vigilance by consumers, industry, academia and government for its safety. However, no definitive cases of toxicity have emerged despite the worldwide usage of 5-HTP for last 20 years, with the possible exception of one unresolved case of a Canadian woman. Extensive analyses of several sources of 5-HTP have shown no toxic contaminants similar to those associated with L-tryptophan, nor the presence of any other significant impurities.

5-HTP has shown promising antidepressant effects, but poor pharmacokinetics limits the therapeutic potential 93. A slow-release delivery mode would be predicted to overcome the pharmacokinetic limitations of 5-HTP, substantially enhance the pharmacological action, and transform 5-HTP into a clinically viable drug.

Native 5-HTP immediate release is a poor serotonergic antidepressant. As discussed below, effective antidepressant therapy requires sustained, minimally fluctuating serotonin (5-HT) elevation 94. A half life (T1/2) = 2 hours means that even at thrice-daily dosing 5-HTP plasma levels will fluctuate at least 5-fold at steady-state. This contrasts to the less than 0.3-fold steady-state plasma fluctuations of most SSRIs 95 (Figure 2). Furthermore, 5-HTP’s fast-onset adverse events likely results from the rapid absorption and resultant serotonin (5-HT) spikes upon administration. Co-administering a peripheral amino acid decarboxylase inhibitor (DCI) (e.g. carbidopa) with 5-HTP will modestly extend the T1/2, several-fold enhance exposure, and not affect TMax 96. Including a peripheral amino acid decarboxylase inhibitor (DCI) in a 5-HTP SR (slow release) drug could be beneficial, but could complicate formulation development, dosing, and safety.

5-HTP may help treat a wide variety of conditions related to low serotonin levels, including the following:

- Depression: Preliminary studies indicate that 5-HTP may work as well as certain antidepressant drugs to treat people with mild-to-moderate depression 97, 98, 99, 100, 101. Like the class of antidepressants known as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), which includes fluoxetine (Prozac) and sertraline (Zoloft), 5-HTP increases the levels of serotonin in the brain. One study compared the effects of 5-HTP to fluvoxamine (Luvox) in 63 people and found that those who were given 5-HTP did just as well as those who received Luvox. They also had fewer side effects than the Luvox group. However, these studies were too small to say for sure if 5-HTP works. More research is needed.

- Fibromyalgia: Research suggests that 5-HTP can improve symptoms of fibromyalgia, including pain, anxiety, morning stiffness, and fatigue. Many people with fibromyalgia have low levels of serotonin, and doctors often prescribe antidepressants. Like antidepressants, 5-HTP raises levels of serotonin in the brain. However, it does not work for all people with fibromyalgia. More studies are needed to understand its effect.

- Insomnia: In one study, people who took 5-HTP went to sleep quicker and slept more deeply than those who took a placebo. Researchers recommend 200 to 400 mg at night to stimulate serotonin, but it may take 6 to 12 weeks to be fully effective.

- Migraines and other headaches: Antidepressants are sometimes prescribed for migraine headaches. Studies suggest that high doses of 5-HTP may help people with various types of headaches, including migraines. However, the evidence is mixed, with other studies showing no effect.

- Obesity: A few small studies have investigated whether 5-HTP can help people lose weight. In one study, those who took 5-HTP ate fewer calories, although they were not trying to diet, compared to those who took placebo. Researchers believe 5-HTP led people to feel more full (satiated) after eating, so they ate less. A follow-up study, which compared 5-HTP to placebo during a diet and non-diet period, found that those who took 5-HTP lost about 2% of body weight during the non-diet period and another 3% when they dieted. Those taking placebo did not lose any weight. However, doses used in these studies were high, and many people experienced side effects such as nausea. If you are seriously overweight, see your health care provider before taking any weight-loss aid. Remember that you will need to change your eating and exercise habits to lose more than a few pounds.

Initial dosage for 5-HTP is usually 50 mg three times a day with meals. If clinical response is inadequate after two weeks, dosage may be increased to 100 mg three times a day 102. For insomnia, the dosage is usually 100-300 mg before bedtime. Because some patients may experience mild nausea when initiating treatment with 5-HTP, it is advisable to begin with 50 mg doses and titrate upward 88.

Side effects of 5-HTP are generally mild and may include nausea, heartburn, gas, feelings of fullness, and rumbling sensations in some people. At high doses, serotonin syndrome, a dangerous condition caused by too much serotonin in the body, could develop. Talk to your doctor before taking higher-than-recommended doses. People with high blood pressure or diabetes should talk to their doctor before taking 5-HTP.

People with liver disease, pregnant women, and women who are breastfeeding should not take 5-HTP.

Do NOT take 5-HTP without medical advice if you are using any of the following medications:

- An antidepressant;

- Carbidopa: Taking 5-HTP with carbidopa, a medication used to treat Parkinson disease, may cause a scleroderma-like illness. Scleroderma is a condition where the skin becomes hard, thick, and inflamed.

- Narcotic medicine;

- Tramadol: Tramadol is used for pain relief and sometimes prescribed for people with fibromyalgia, may raise serotonin levels too much if taken with 5-HTP. Serotonin syndrome has been reported in some people taking the two together.

- Cough medicine that contains dextromethorphan: Taking 5-HTP with dextromethorphan, found in cough syrups, may cause serotonin levels to increase to dangerous levels, a condition called serotonin syndrome.

- Meperidine (Demerol): Taking 5-HTP with Demerol may cause serotonin levels to increase to dangerous levels, a condition called serotonin syndrome.

- Triptans (used to treat migraines): 5-HTP can increase the risk of side effects, including serotonin syndrome, when taken with these medications:

- Naratriptan (Amerge)

- Rizatriptan (Maxalt)

- Sumatriptan (Imitrex)

- Zolmitriptan (Zomig)

Some antidepressant medications that can interact with 5-HTP include:

- SSRIs: Citalopram (Celexa), escitalopram (Lexapro), fluvoxamine (Luvox), paroxetine (Paxil), fluoxetine (Prozac), sertraline (Zoloft)

- Tricyclics: Amitriptyline (Elavil), nortriptyline (Pamelor), imipramine (Tofranil)

- Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs): Phenelzine, (Nardil), tranylcypromine (Parnate)

- Nefazodone (Serzone)

If you take antidepressants, you should not take 5-HTP without your doctor’s supervision. These medications could combine with 5-HTP to cause serotonin syndrome, a dangerous condition involving mental changes, hot flashes, rapidly fluctuating blood pressure and heart rate, and possibly coma.

This list is not complete. Other drugs may interact with 5-HTP, including prescription and over-the-counter medicines, vitamins, and herbal products. Not all possible interactions are listed here.

Figure 1. Synthesis of 5-HTP from tryptophan

Footnotes: (A) 5-hydroxytryptamine (serotonin) metabolic pathway. Synthesis of 5-HTP from tryptophan via TPH 1 (periphery) or TPH 2 (CNS) is the rate-limiting step in 5-HT synthesis. 5-HTP is rapidly converted to 5-hydroxytryptamine (serotonin) by the ubiquitous enzyme amino acid decarboxylase. 5-hydroxytryptamine (serotonin) is metabolized to 5-HIAA, 5-hydroxytryptamine (serotonin) main metabolite, by monoamine oxidase. (B) Simplified schematic of regulatory elements of CNS 5-HTExt. Drugs interacting with each element are indicated. (C) Schematic for adjunct 5-HTP SR mechanism-of-action. Adjunct exogenous 5-HTP increases endogenous 5-hydroxytryptamine (serotonin) synthesis, increasing availability of 5-hydroxytryptamine (serotonin) for net release by concomitant SERT inhibitor treatment.

Abbreviations: 5-HT = 5-hydroxytryptamine (serotonin); 5-HTExt = extracellular 5-HT; 5-HTP = 5-hydroxytryptopan; 5-HIAA = 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid; AADC = aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase, also known as DOPA decarboxylase; MOA = monoamine oxidase; MOA I = monoamine oxidase inhibitor; SERT= serotonin transporter; SERT I = serotonin transporter inhibitor; SR = slow-release; TPH = tryptophan hydroxylase.

[Source 103]Figure 2. 5-HTP pharmacokinetics simulation