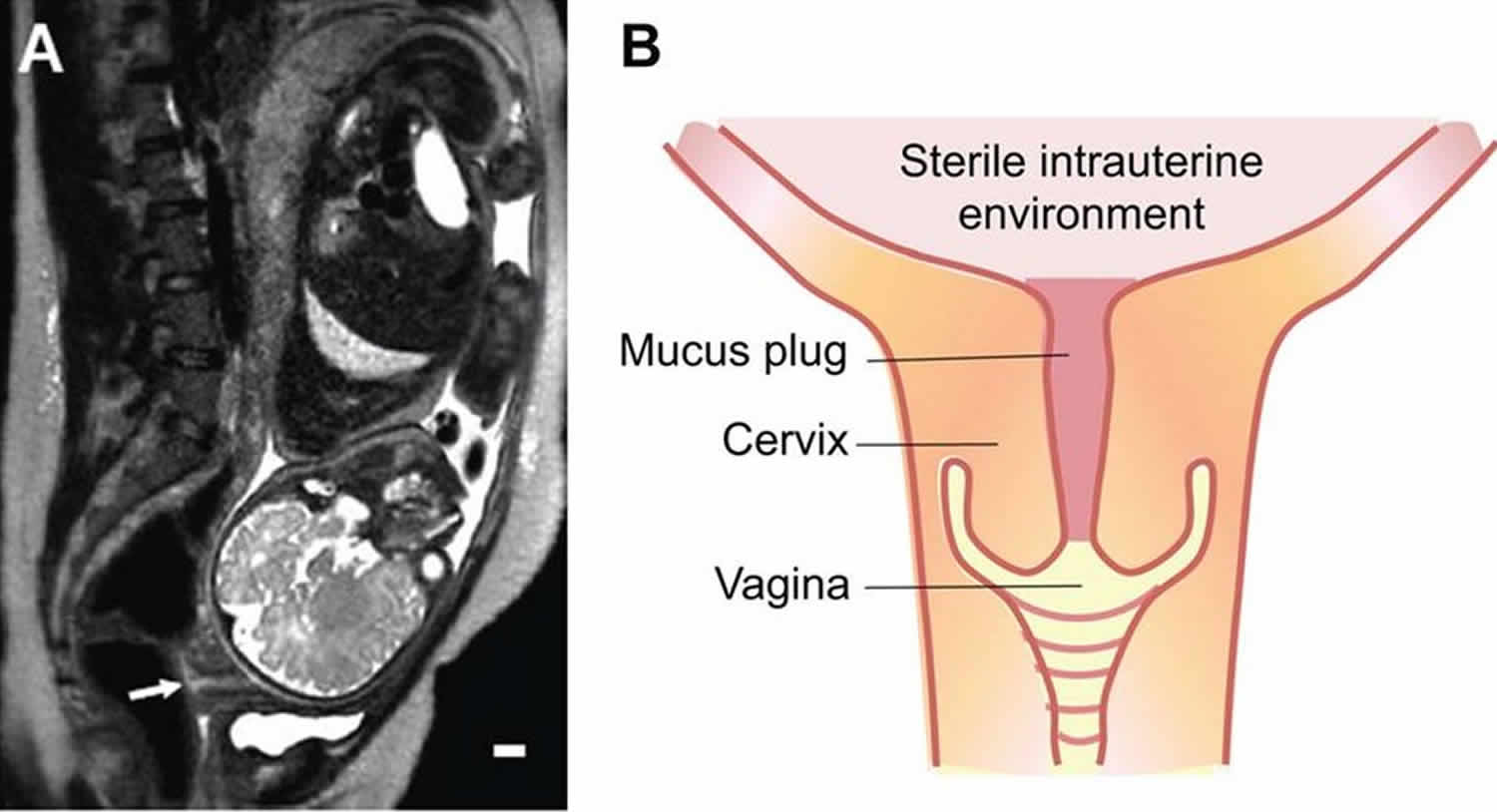

Cervical mucus plug

A cervical mucus plug (operculum) is a plug that fills and seals the cervical canal during pregnancy. It is formed by a small amount of cervical mucus. The cervical mucus plug acts as a protective barrier by deterring the passage of bacteria into the uterus, and contains a variety of antimicrobial agents, including immunoglobulins, and similar antimicrobial peptides to those found in nasal mucus. In the female reproductive system, cervical mucus prevents infection and helps the movement of the penis during sexual intercourse. When thin, cervical mucus helps the movement of spermatozoa. The consistency of cervical mucus varies depending on the stage of a woman’s menstrual cycle. At ovulation cervical mucus is clear, runny, and conducive to sperm; post-ovulation, mucus becomes thicker and is more likely to block sperm.

Normally during human pregnancy, the mucus is cloudy, clear, thick, and sticky. Toward the end of the pregnancy, when the cervix thins, some blood is released into the cervix which causes the mucus to become bloody. As the woman gets closer to labor, the mucus plug discharges as the cervix begins to dilate. The plug may come out as a plug, a lump, or simply as increased vaginal discharge over several days. The mucus may be tinged with brown, pink, or red blood, which is why the event is sometimes referred to as “bloody show”. Loss of the mucus plug does not necessarily mean that delivery or labor is imminent.

Having intercourse or a vaginal examination can also disturb the mucus plug and cause a woman to see some blood-tinged discharge, even when labor does not begin over the next few days.

The cervical canal is filled with mucus, a ubiquitous hydrogel that lines all wet surfaces in the body including the respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts. Its main gelforming constituents are the mucin glycoproteins, which entangle to form a viscoelastic hydrogel 1. The mucus barrier functions to both shield the underlying epithelia from infectious agents and other environmental particles/pathogens while allowing selective passage to nutrients, ions, gases, proteins and sperm 1. Cervical mucus is secreted from goblet cells within crypts lining the cervical canal 2 and, during pregnancy, condenses to form a large compact structure commonly known as the ‘‘cervical mucus plug’’ that is shed prior to delivery 3. The cervical mucus plug in normal pregnancy has properties of both innate and adaptive immunity 4, and is, therefore, thought to play a vital protective role during pregnancy 3. However, a detailed understanding of the barrier properties of cervical mucus is not understood.

The basic difference between the cervical mucus plug of pregnant women and the cervical mucus of non-pregnant women is that the cervical mucus plug is in direct contact with the supracervical region of the chorioamniotic membranes which contain amniotic fluid 5. As expected, several proteins documented in the amniotic fluid and the amnion were identified in the cervical mucus plug. Resistin and retinol binding protein 4 were present in the cervical mucus plugs, and scientists previously have shown these two adipokines are increased in amniotic fluid in the presence of intra-amniotic infection/inflammation6. Insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 1 (IGFBP1) is also detected in the amniotic fluid, and its 13.5 kD fragment is detected in cases with intra-amniotic infection 7. It is also noteworthy that apolipoprotin A-II and apoplipoprotein B-100 are components of cholesterol metabolism, which have been demonstrated in the amniotic fluid but not in the cervical mucus or the cervicovaginal fluid. Therefore, proteins in the amniotic fluid seem to be easily integrated into the cervical mucus plug. In this context, the cervical mucus plug is an ideal venue through which the changes in the intrauterine compartment could be coordinated with the uterine cervix throughout pregnancy. Furthermore, the findings strongly suggest a possibility that the cervical mucus plug can be used for the diagnosis of certain genetic and metabolic diseases of the fetus.

Cervical plug during pregnancy

The cervical mucus plug differs from the cervical secretions of non-pregnant women, and is the ultimate sealant of the uterine cavity during pregnancy 5. Although several studies have analyzed biochemical properties of large glycoproteins in the cervical mucus plug, comprehensive information about its protein composition is yet unavailable. The primary finding is that several proteins documented in the amniotic fluid and the chorioamniotic membranes are found in the cervical mucus plug in addition to a variety of proteins involved in the immune response such as complements and neutrophil defensins 5. The results of this study 5 further underscore the functional significance of the cervical mucus plug as a critical ‘gate-keeper’ based on its physiological and immunologic properties 8. Mucus glycoproteins (mucins) are the core proteins of the cervical mucus plug, provide the structural framework, and inhibit diffusion of large molecules and bacteria 9. Cervical mucus plug proteins such as lactoferrin, lysozyme, neutrophil defensin, haptoglobin, and leukocyte elastase inhibitor are involved in host defense, and also have been found in cervical mucus, cervicovaginal fluid, and amniotic fluid 10. Peptidoglycan recognition protein was also detected in our analysis. In addition to this catalogue of anti-microbial peptides, the T-cell inhibitory molecule, glycodelin-A, which is largely produced by decidua, and pregnancy zone protein were also detected. Pregnancy zone protein belongs to the alpha 2 macroglobulin family, and can bind vascular endothelial grvowth factor, placental growth factor, and glycodelin-A, all of which have critical biological importance in pregnancy 11. Pregnancy zone protein is an effective carrier of glycodelin-A, and these two molecules showed synergistic inhibitory effects on T cell proliferation and IL-2 production 12. Therefore, the cervical mucus plug appears to protect the intrauterine fetal compartments from both the spread of microbial pathogens and the maternal anti-fetal immune response.

- Critchfield, Agatha & Yao, Grace & Jaishankar, Aditya & Friedlander, Ronn & Lieleg, Oliver & Doyle, Patrick & Mckinley, Gareth & House, Michael & Ribbeck, Katharina. (2013). Cervical Mucus Properties Stratify Risk for Preterm Birth. PloS one. 8. e69528. 10.1371/journal.pone.0069528. [↩][↩]

- Chantler E, Elstein M (1986) STRUCTURE AND FUNCTION OF CERVICAL-MUCUS. Seminars in Reproductive Endocrinology 4: 333–342.[↩]

- Becher N, Waldorf KA, Hein M, Uldbjerg N (2009) The cervical mucus plug: Structured review of the literature. Acta Obstetricia Et Gynecologica Scandinavica 88: 502–513.[↩][↩]

- Hein M, Petersen AC, Helmig RB, Uldbjerg N, Reinholdt J (2005) Immunoglobulin levels and phagocytes in the cervical mucus plug at term of pregnancy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 84: 734–742.[↩]

- Lee DC, Hassan SS, Romero R, et al. Protein profiling underscores immunological functions of uterine cervical mucus plug in human pregnancy. J Proteomics. 2011;74(6):817–828. doi:10.1016/j.jprot.2011.02.025 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3111960[↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Romero R, Kusanovic JP, Gotsch F, Erez O, Vaisbuch E, Mazaki-Tovi S, Moser A, Tam S, Leszyk J, Master SR, Juhasz P, Pacora P, Ogge G, Gomez R, Yoon BH, Yeo L, Hassan SS, Rogers WT. Isobaric labeling and tandem mass spectrometry: a novel approach for profiling and quantifying proteins differentially expressed in amniotic fluid in preterm labor with and without intra-amniotic infection/inflammation. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2010;23:261–280.[↩]

- Bujold E, Romero R, Kusanovic JP, Erez O, Gotsch F, Chaiworapongsa T, Gomez R, Espinoza J, Vaisbuch E, Mee KY, Edwin S, Pisano M, Allen B, Podust VN, Dalmasso EA, Rutherford J, Rogers W, Moser A, Yoon BH, Barder T. Proteomic profiling of amniotic fluid in preterm labor using two-dimensional liquid separation and mass spectrometry. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2008;21:697–713.[↩]

- Hein M, Petersen AC, Helmig RB, Uldbjerg N, Reinholdt J. Immunoglobulin levels and phagocytes in the cervical mucus plug at term of pregnancy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2005;84:734–742.[↩]

- Becher N, Waldorf KA, Hein M, Uldbjerg N. The cervical mucus plug: structured review of the literature. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2009;88:502–513.[↩]

- Panicker G, Lee DR, Unger ER. Optimization of SELDI-TOF protein profiling for analysis of cervical mucous. J Proteomics. 2009;71:637–646.[↩]

- Tayade C, Esadeg S, Fang Y, Croy BA. Functions of alpha 2 macroglobulins in pregnancy. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2005;245:60–66.[↩]

- Skornicka EL, Kiyatkina N, Weber MC, Tykocinski ML, Koo PH. Pregnancy zone protein is a carrier and modulator of placental protein-14 in T-cell growth and cytokine production. Cell Immunol. 2004;232:144–156.[↩]