Cervical radiculopathy

Cervical radiculopathy also called a “pinched nerve” in the neck occurs when a nerve in the neck is compressed or irritated where it branches away from the spinal cord. This may cause neck pain that radiates into your shoulder, as well as muscle weakness and numbness that travels down the arm and into your hand.

Cervical radiculopathy is often caused by “wear and tear” changes that occur in the spine as we age, such as arthritis. In younger people, it is most often caused by a sudden injury that results in a herniated disk.

In most cases, cervical radiculopathy responds well to conservative treatment that includes medication and physical therapy.

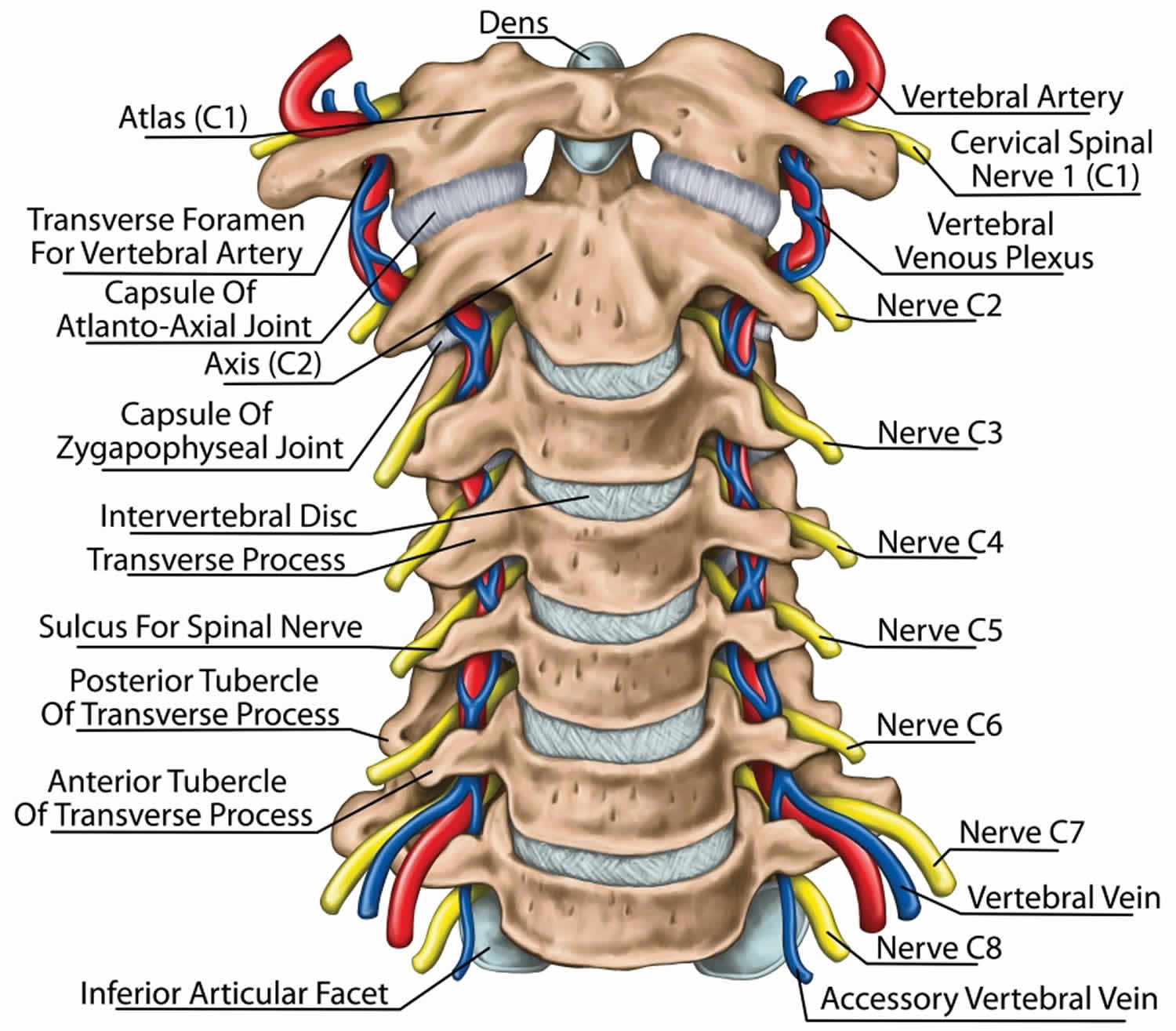

Cervical spine anatomy

Your spine is made up of 24 bones, called vertebrae, that are stacked on top of one another. These bones connect to create a canal that protects the spinal cord.

The seven small vertebrae that begin at the base of the skull and form the neck comprise the cervical spine.

Other parts of your spine include:

- Spinal cord and nerves. These “electrical cables” travel through the spinal canal carrying messages between your brain and muscles. Nerve roots branch out from the spinal cord through openings in the vertebrae (foramen).

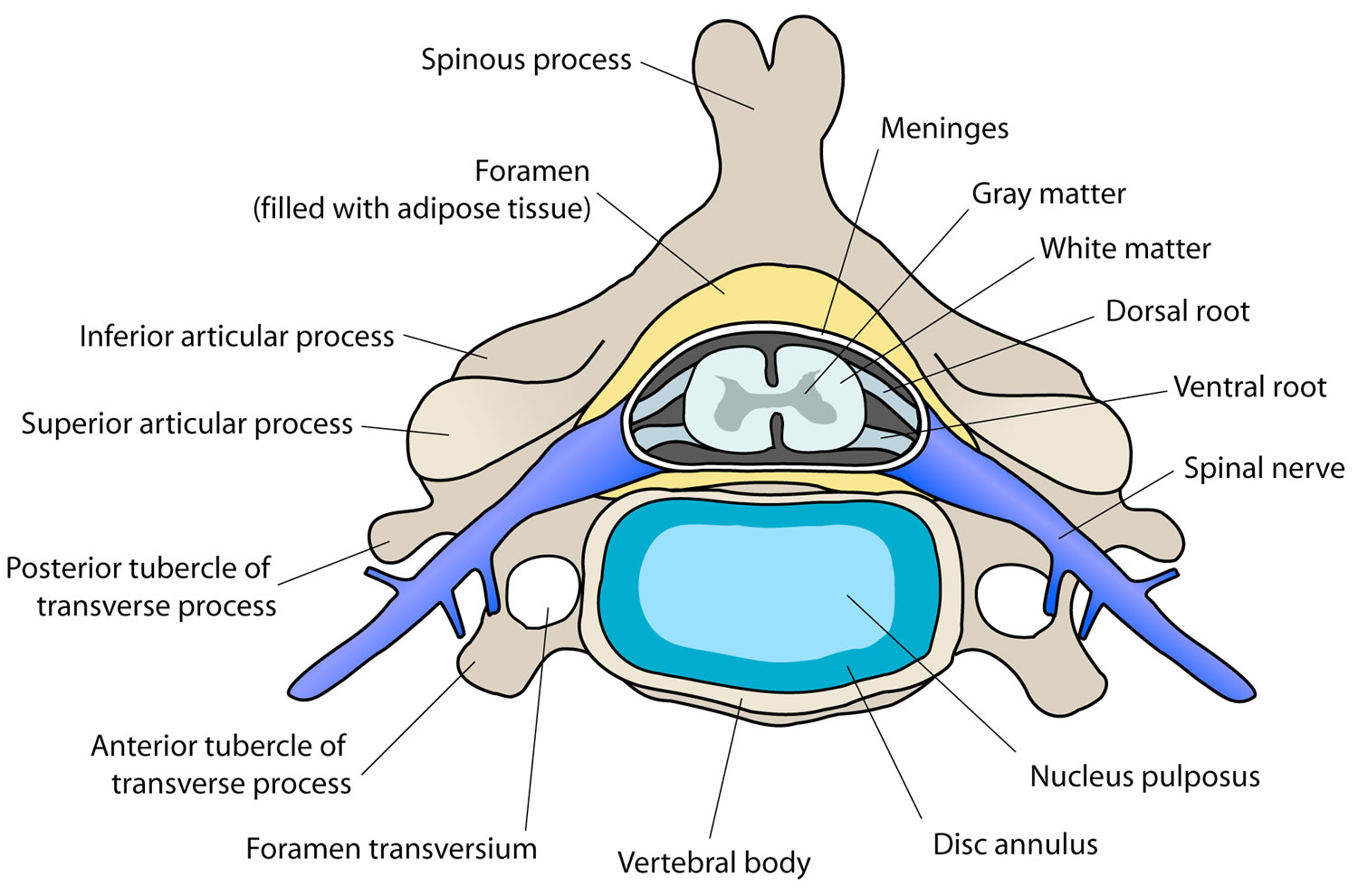

- Intervertrebral disks. In between your vertebrae are flexible intervertebral disks. They act as shock absorbers when you walk or run.

Intervertebral disks are flat and round and about a half inch thick. They are made up of two components:

- Annulus fibrosus. This is the tough, flexible outer ring of the disk.

- Nucleus pulposus. This is the soft, jelly-like center of the disk.

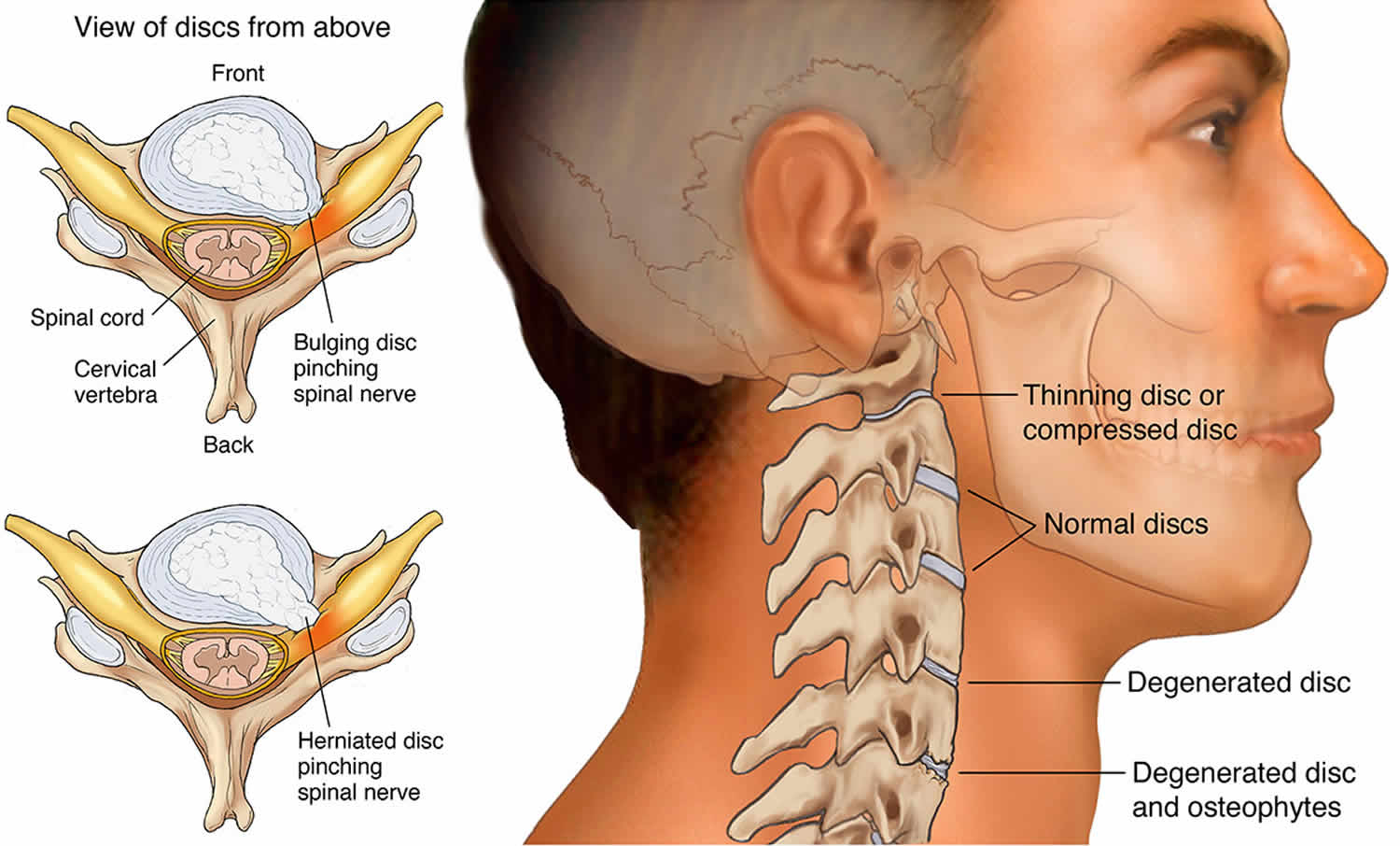

Figure 1. Cervical spine

Figure 2. Cervical disc

Cervical radiculopathy causes

Several conditions can put pressure on nerve roots in your neck.

The most common causes for cervical radiculopathy are:

- Herniated cervical disk. In this situation, the outer layer (annulus) of the disk cracks and the gel-like center (nucleus) breaks through. This causes the disk to protrude, putting pressure on the nerve that exits the spinal column at that point.

- Spinal stenosis. Sometimes, the space in the center of the vertebrae narrows and squeezes the spinal column and nerve roots.

- Degenerative disk disease. As we age, the water content in our body cells diminishes and other chemical changes occur that can cause the disk to shrink. Without sufficient cushioning, the vertebrae may begin to press against each other, pinching the nerve, or to form bony spurs.

- Other less common causes of mechanical compression of the nerves is from a tumor or infection. Either of these can reduce the amount of space in the spinal canal and compress the exiting nerve.

- Scoliosis can cause the nerves on one side of the spine to become compressed by the abnormal curve of the spine.

Cervical radiculopathy most often arises from degenerative changes that occur in the spine as you age or from an injury that causes a herniated, or bulging, intervertebral disk.

Degenerative changes

As the disks in the spine age, they lose height and begin to bulge. They also lose water content, begin to dry out, and become stiffer. This problem causes settling, or collapse, of the disk spaces and loss of disk space height.

As the disks lose height, the vertebrae move closer together. The body responds to the collapsed disk by forming more bone —called bone spurs—around the disk to strengthen it. These bone spurs contribute to the stiffening of the spine. They may also narrow the foramen—the small openings on each side of the spinal column where the nerve roots exit—and pinch the nerve root.

Degenerative changes in the disks are often called arthritis or spondylosis. These changes are normal and they occur in everyone. In fact, nearly half of all people middle-aged and older have worn disks and pinched nerves that do not cause painful symptoms. It is not known why some patients develop symptoms and others do not.

Herniated disk

A disk herniates when its jelly-like center (nucleus) pushes against its outer ring (annulus). If the disk is very worn or injured, the nucleus may squeeze all the way through. When the herniated disk bulges out toward the spinal canal, it puts pressure on the sensitive nerve root, causing pain and weakness in the area the nerve supplies.

A herniated disk often occurs with lifting, pulling, bending, or twisting movements.

Risk factors for developing cervical radiculopathy

Risk factors for cervical radiculopathy are activities that place an excessive or repetitive load on the spine of neck. These include:

- Old age

- Degenerative joint disease

- High-impact sports

- Osteoporosis

- Accidental injuries to the neck

Cervical radiculopathy symptoms

In most cases, the pain of cervical radiculopathy starts at the neck and travels down the arm in the area served by the damaged nerve. This pain is usually described as burning or sharp. Certain neck movements—like extending or straining the neck or turning the head—may increase the pain. Other symptoms include:

- Tingling or the feeling of “pins and needles” in the fingers or hand

- Weakness in the muscles of the arm, shoulder, or hand

- Loss of sensation

Some patients also complain that certain movements may worsen the symptoms of cervical radicuolpathy. These include extending or straining the neck or turning the head.

Some patients report that pain decreases when they place their hands on top of their head and stretching the shoulder actually relieve cervical radiculopathy pain and discomfort. This movement may temporarily relieve pressure on the nerve root.

Cervical radiculopathy complications

It is important to receive prompt attention for cervical radiculopathy. Untreated conditions may progress and cause further injury. Advanced cervical radiculopathy can cause muscle wasting, and the symptoms may spread to the legs.

Cervical radiculopathy diagnosis

After discussing your medical history and general health, your doctor will ask you about your symptoms. He or she will then examine your neck, shoulder, arms and hands—looking for muscle weakness, loss of sensation, or any change in your reflexes.

Your doctor may also ask you to perform certain neck and arm movements to try to recreate and/or relieve your symptoms.

Imaging studies

- X-rays. These provide images of dense structures, such as bone. An x-ray will show the alignment of bones along your neck. It can also reveal whether there is any narrowing of the foramen and damage to the disks.

- Computed tomography (CT) scans. More detailed than a plain x-ray, a CT scan can help your doctor determine whether you have developed bone spurs near the foramen in your cervical spine.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans. These studies create better images of the body’s soft tissues. An MRI of the neck can show if your nerve compression is caused by damage to soft tissues—such as a bulging or herniated disk. It can also help your doctor determine whether there is any damage to your spinal cord or nerve roots.

- Electromyography (EMG). Electromyography measures the electrical impulses of the muscles at rest and during contractions. Nerve conduction studies are often done along with EMG to determine if a nerve is functioning normally. Together, these tests can help your doctor determine whether your symptoms are caused by pressure on spinal nerve roots and nerve damage or by another condition that causes damage to nerves, such as diabetes.

Cervical radiculopathy treatment

It is important to note that the majority of patients with cervical radiculopathy get better over time and do not need treatment. For some patients, the pain goes away relatively quickly—in days or weeks. For others, it may take longer.

It is also common for cervical radiculopathy that has improved to return at some point in the future. Even when this occurs, it usually gets better without any specific treatment.

In some cases, cervical radiculopathy does not improve, however. These patients require evaluation and treatment.

Nonsurgical treatment

Initial treatment for cervical radiculopathy is nonsurgical. Nonsurgical treatment options include:

- Soft cervical collar. This is a padded ring that wraps around the neck and is held in place with Velcro. Your doctor may advise you to wear a soft cervical collar to allow the muscles in your neck to rest and to limit neck motion. This can help decrease the pinching of the nerve roots that accompany movement of the neck. A soft collar should only be worn for a short period of time since long-term wear may decrease the strength of the muscles in your neck.

- Physical therapy. Specific exercises can help relieve pain, strengthen neck muscles, and improve range of motion. In some cases, traction can be used to gently stretch the joints and muscles of the neck.

- Medications. In some cases, medications can help improve your symptoms.

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). NSAIDs, including aspirin, ibuprofen, and naproxen, may provide relief if your pain is caused by nerve irritation or inflammation.

- Oral corticosteroids. A short course of oral corticosteroids may help relieve pain by reducing swelling and inflammation around the nerve.

- Narcotics. These medications are reserved for patients with severe pain that is not relieved by other options. Narcotics are usually prescribed for a limited time only.

- Steroid injection. In this procedure, steroids are injected near the affected nerve to reduce local inflammation. The injection may be placed between the laminae (epidural injection), in the foramen (selective nerve injection), or into the facet joint. Although steroid injections do not relieve the pressure on the nerve caused by a narrow foramen or by a bulging or herniated disk, they may lessen the swelling and relieve the pain long enough to allow the nerve to recover.

If after a period of time nonsurgical treatment does not relieve your symptoms, your doctor may recommend surgery. There are several surgical procedures to treat cervical radiculopathy. The procedure your doctor recommends will depend on many factors, including what symptoms you are experiencing and the location of the involved nerve root.

Cervical radiculopathy surgery

When symptoms of cervical radiculopathy persist or worsen despite nonsurgical treatment, your doctor may recommend surgery.

The primary goal of surgery is to relieve your symptoms by decompressing, or relieving pressure on, the compressed nerves in your neck. Other goals of surgery include:

- Improving neck pain

- Maintaining stability of the spine

- Improving alignment of the spine

- Preserving range of motion in the neck

In most cases, surgery for cervical radiculopathy involves removing pieces of bone or soft tissue (such as a herniated disk) or both. This relieves pressure by creating more space for the nerves to exit the spinal canal.

There are three surgical procedures commonly performed to treat cervical radiculopathy. They are:

- Anterior cervical diskectomy and fusion

- Artificial disk replacement

- Posterior cervical laminoforaminotomy

The procedure your doctor recommends will depend on a number of factors–most importantly, the type and location of your problem. Other factors include:

Your preference for a procedure

Your doctor’s preference and experience

Your overall health and medical history (including whether you have had prior neck surgery)

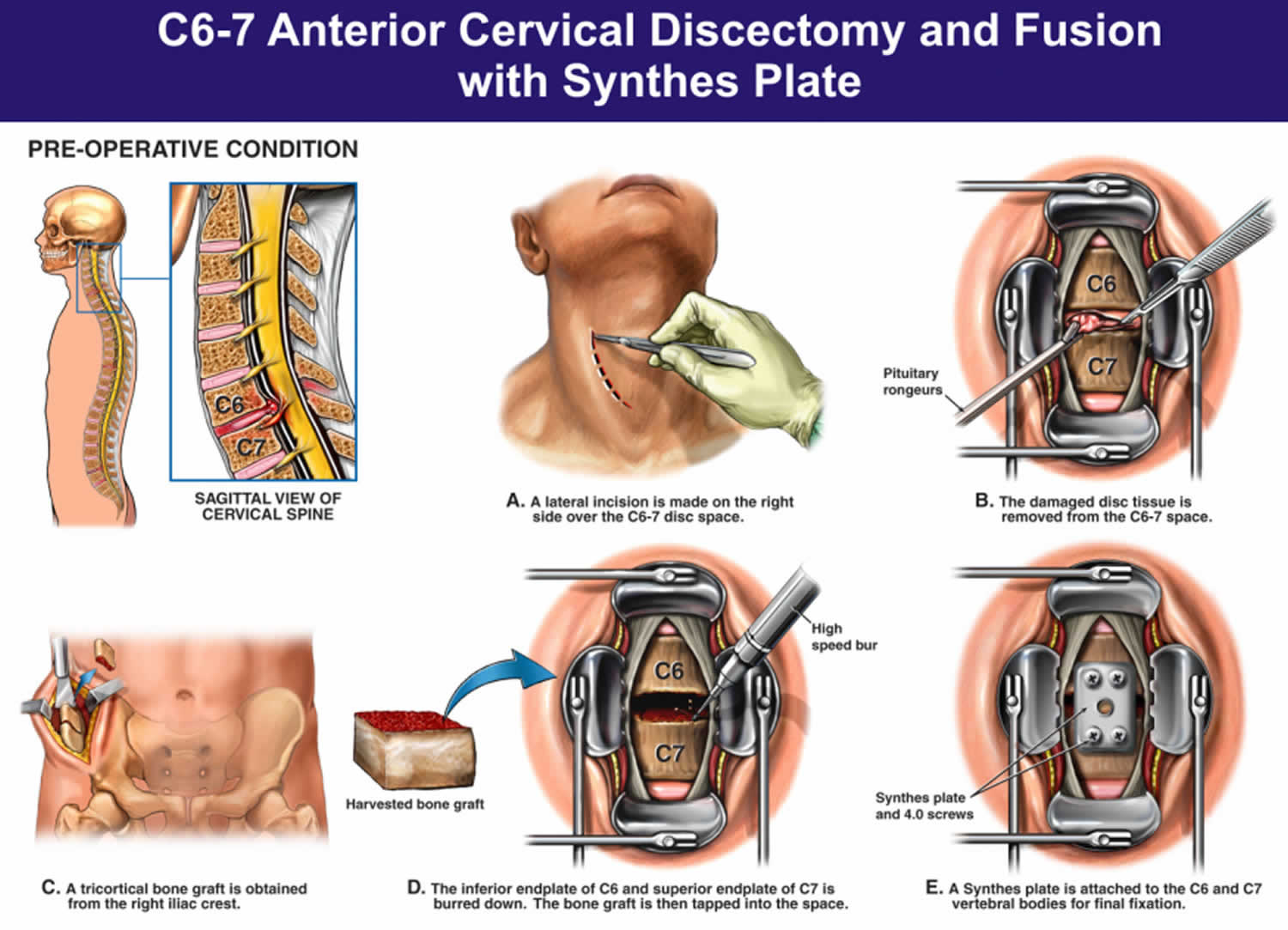

Anterior cervical diskectomy and fusion

Anterior cervical discectomy and fusion is the most commonly performed procedure to treat cervical radiculopathy. The procedure involves removing the problematic disk or bone spurs and then stabilizing the spine through spinal fusion.

The goals of anterior cervical diskectomy and fusion are to:

- Restore alignment of the spine

- Maintain the space available for the nerve roots to leave the spine

- Limit motion across the degenerated segment of the spine

Anterior cervical discectomy and fusion procedure

An “anterior” approach means that the doctor will approach your neck from the front. He or she will operate through a 1- to 2-inch incision along the neck crease. The exact location and length of your incision may vary depending on your specific condition.

During the procedure, your doctor will remove the problematic disk and any additional bone spurs, if necessary. The disk space is restored to the height it was prior to the disk wearing out. This makes more room for the nerves to leave the spine and aids in decompression.

Spinal fusion

After the disk space has been cleared out, your doctor will use spinal fusion to stabilize your spine. Spinal fusion is essentially a “welding” process. The basic idea is to fuse together the vertebrae so that they heal into a single, solid bone. Fusion eliminates motion between the degenerated vertebrae and takes away some spinal flexibility. The theory is that if the painful spine segments do not move, they should not hurt.

All spinal fusions use some type of bone material, called a bone graft, to help promote the fusion. The small pieces of bone are placed into the space left where the disk has been removed. Sometimes larger, solid pieces are used to provide immediate structural support to the vertebrae.

In some cases, the doctor may implant a metal, plastic, or bone spacer between the two adjoining vertebrae. This spacer, or “cage,” usually contains bone graft material to allow a spinal fusion to occur between the two vertebrae.

After the bone graft is placed or the cage is inserted, your doctor will use metal screws, plates and rods to increase the rate of fusion and further stabilize the spine.

Bone graft sources

The bone graft will come from either your own bone (autograft) or from a donor (allograft). If an autograft is used, the bone is usually taken from your hip area. Harvesting the bone graft requires an additional incision during your surgery. It lengthens surgical time and may cause increased pain after the operation. Your doctor will talk to you about the advantages and disadvantages of using an autograft versus an allograft, as well as a traditional bone graft versus a cage.

Figure 3. Anterior cervical discectomy and fusion

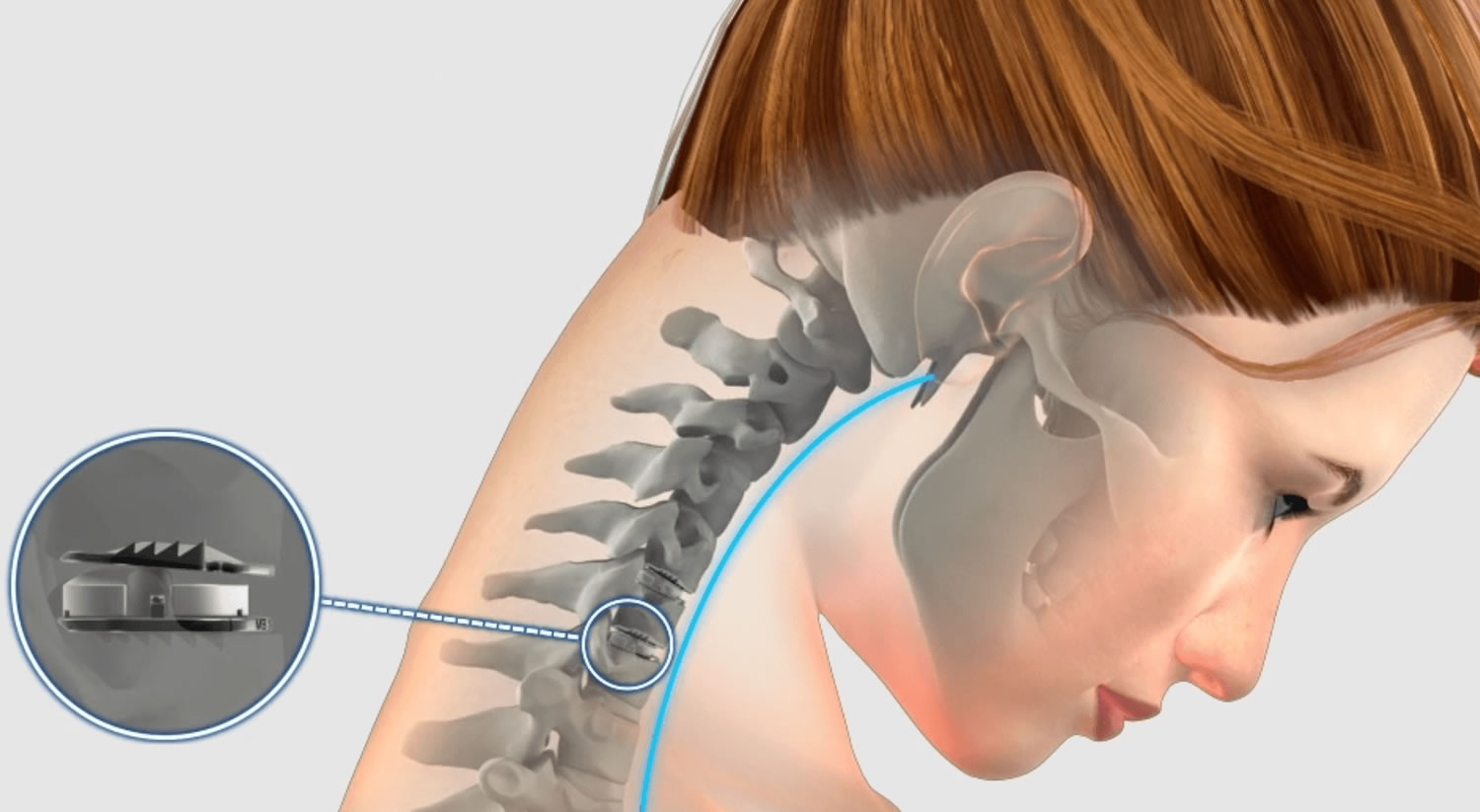

Artificial disk replacement

This procedure involves removing the degenerated disk and replacing it with artificial parts, as is done in hip or knee replacement. The goal of disk replacement is to allow the spinal segment to keep some flexibility and maintain more normal motion.

Similar to anterior cervical discectomy and fusion, your doctor will use an “anterior” approach for the surgery—making a 1- to 2-inch incision along the neck crease. The exact location and length of your incision may vary depending on your specific condition.

During the surgery, your doctor will remove your problematic disc and then insert an artificial disc implant into the disc space. The implant is made of all metal or metal and plastic. It is designed to maintain the motion between the vertebrae after the degenerated disk has been removed. The implant may help restore the height between the vertebrae and widen the passageway for the nerve roots to exit the spinal canal.

Although no longer considered a new technology, the development of artificial disc replacement is more recent than that of anterior cervical discectomy and fusion. To date, the outcomes of artificial disc replacement surgery are promising and are comparable to that of anterior cervical discectomy and fusion surgery. The long-term outcomes are still being researched.

Artificial disc replacement may be an option for you, depending on the type and location of your problem. Your doctor will talk with you about your options.

Figure 4. Artificial disc replacement

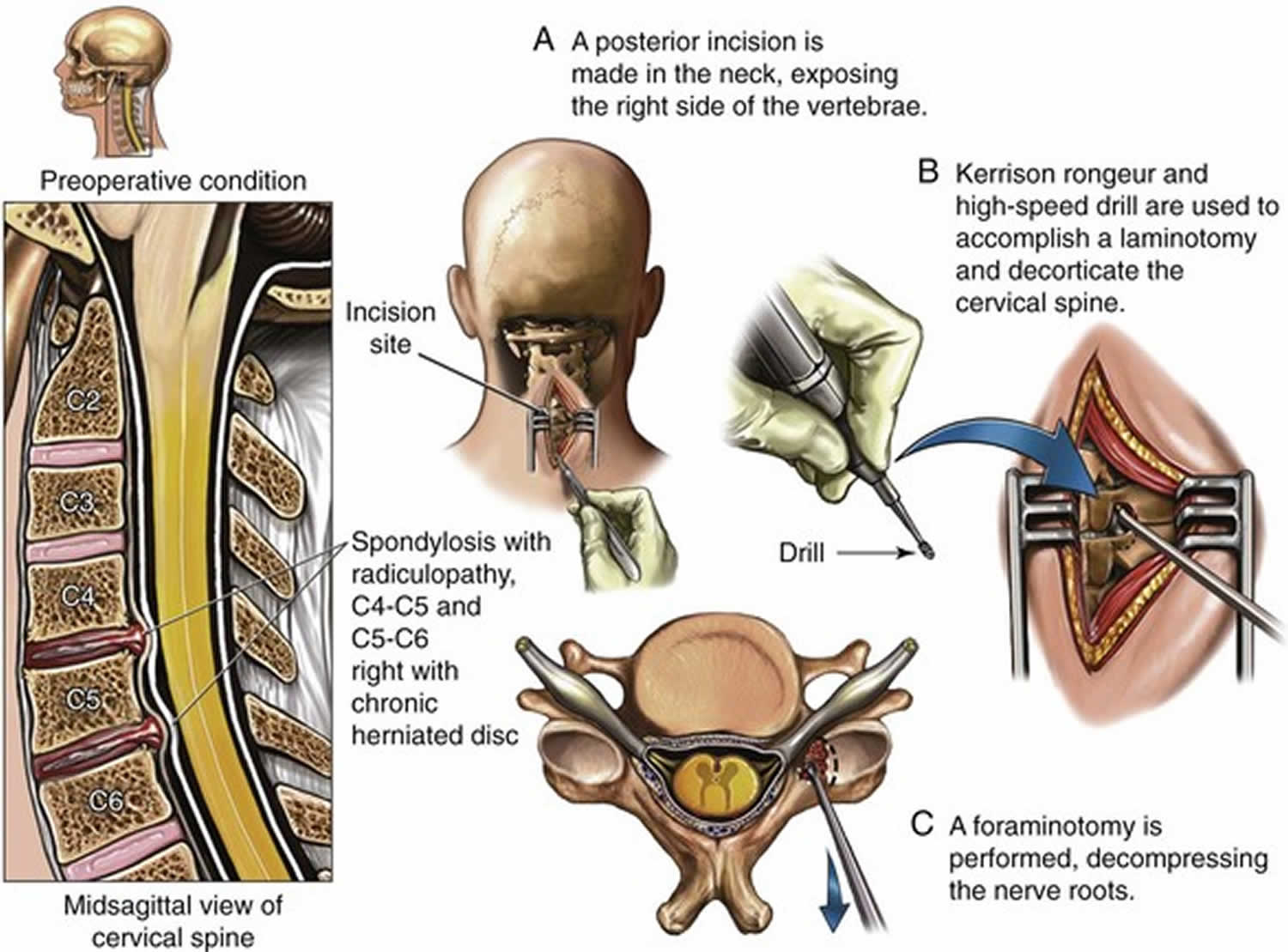

Posterior cervical laminoforaminotomy

“Posterior” refers to the back part of your body. In this procedure, the doctor will make a 1- to 2-inch incision along the midline of the back of the neck. The exact location and size of your scar may vary depending on your condition.

During a posterior cervical laminoforaminotomy, the doctor uses a burr and other specialized tools to thin down the lamina—the bony arch that forms the backside of the spinal canal. Removing this allows the doctor better access to the damaged nerve.

He or she then removes the bone, bone spurs, and tissues that are compressing the nerve root. If your compression is due to a herniated disk, your doctor will remove the portion of the disk that is compressing the nerve, as well.

Unlike anterior cervical discectomy and fusion, posterior cervical laminoforaminotomy does not require spinal fusion to stabilize the spine. Because of this, you will maintain better range of motion in your neck and your recovery will be quicker.

The procedure can be performed as open surgery, in which your doctor uses a single, larger incision to access your spine. It can also be done using a minimally invasive method, where several smaller incisions are made. Your doctor will discuss with you whether posterior cervical laminoforaminotomy is an option for you and, if so, how the surgery will be performed.

Figure 5. Posterior cervical laminoforaminotomy

Cervical radiculopathy surgery complications

As with any surgical procedure, there are risks associated with cervical spine surgery. Possible complications can be related to the approach used, the bone graft, healing, and long-term changes. Before your surgery, your doctor will discuss each of the risks with you and will take specific measures to help avoid potential complications.

General risks

The possible risks and complications for any cervical spine surgery include:

- Infection

- Bleeding

- Nerve injury

- Spinal cord injury

- Reaction to anesthesia

- The need for additional surgery in the future

- Failure to relieve symptoms

- Tear of the sac covering the nerves (dural tear)

- Life-threatening medical problems, such as heart attack, lung complications, or stroke

Anterior cervical diskectomy and fusion and artificial disk replacement risks

There are additional potential risks and complications when an anterior approach is used in spine surgery. They include:

- Misplaced, broken, or loosened plates, screws, or implants

- Soreness or difficulty with swallowing

- Voice changes

- Breathing difficulty

- Injury to the esophagus

- Pain at the site the bone was taken from—if an autograft is used

- Nonunion of the spinal fusion (in anterior cervical discectomy and fusion)

Recovery

After surgery, you will typically stay in the hospital for 1 or 2 days. This will vary, however, depending on the type of surgery you have had and how many disk levels were involved.

Most patients are able to walk and eat on the first day after surgery. It is normal to have difficulty swallowing solid foods for a few weeks or have some hoarseness following anterior cervical spine surgery.

You may need to wear a soft or a rigid cervical collar at first. How long you should wear it will depend on the type of surgery you have had.

After spinal fusion, it may take from 6 to 12 months for the bone to become solid. Because of this, your doctor will give you specific restrictions for some time period after your surgery. Right after your operation, your doctor may recommend only light activity, like walking. As you regain strength, you will be able to slowly increase your activity level.

Physical therapy

Usually by 4 to 6 weeks, you can gradually begin to do range-of-motion and strengthening exercises. Your doctor may prescribe physical therapy during the recovery period to help you regain full function.

Return to work

Most people are able to return to a desk job within a few days to a few weeks after surgery. They may be able to return to full activities by 3 to 4 months, depending on the procedure. For some people, healing may take longer.

Outcomes

Most patients experience favorable outcomes after surgery for cervical radiculopathy. In most cases, they experience relief from their pain and other symptoms and are able to successfully return to the activities of daily life after a period of recovery.