Clonorchiasis

Clonorchiasis is an infection with a liver fluke parasite Clonorchis sinensis that infect humans due to eating raw or undercooked fish, crabs, or crayfish from areas where the Clonorchis sinensis parasite is found 1. Clonorchis is found mainly in Korea, China, Taiwan, Northern Vietnam, Japan, and Asian Russia. Clonorchis is also known as the Chinese or oriental liver fluke (trematodes or worms). Travelers to Asia who consume raw or undercooked fish are at risk for liver fluke infection. Liver flukes infect the liver, gallbladder, and bile duct in humans. After ingestion, these liver flukes grow to adulthood inside the human biliary duct system. While most infected persons do not show any symptoms, Clonorchis infections that last a long time can result in severe symptoms and serious illness. Untreated, Clonorchis infections may persist for up to 25–30 years, the lifespan of the Clonorchis sinensis parasite. Adequately freezing or cooking fish will kill the parasite.

Diagnosis of Clonorchis infection is based on microscopic identification of the parasite’s eggs in stool specimens. Safe and effective medication is available to treat Clonorchis infections. Praziquantel or albendazole are the drugs of choice to treat Clonorchis infection.

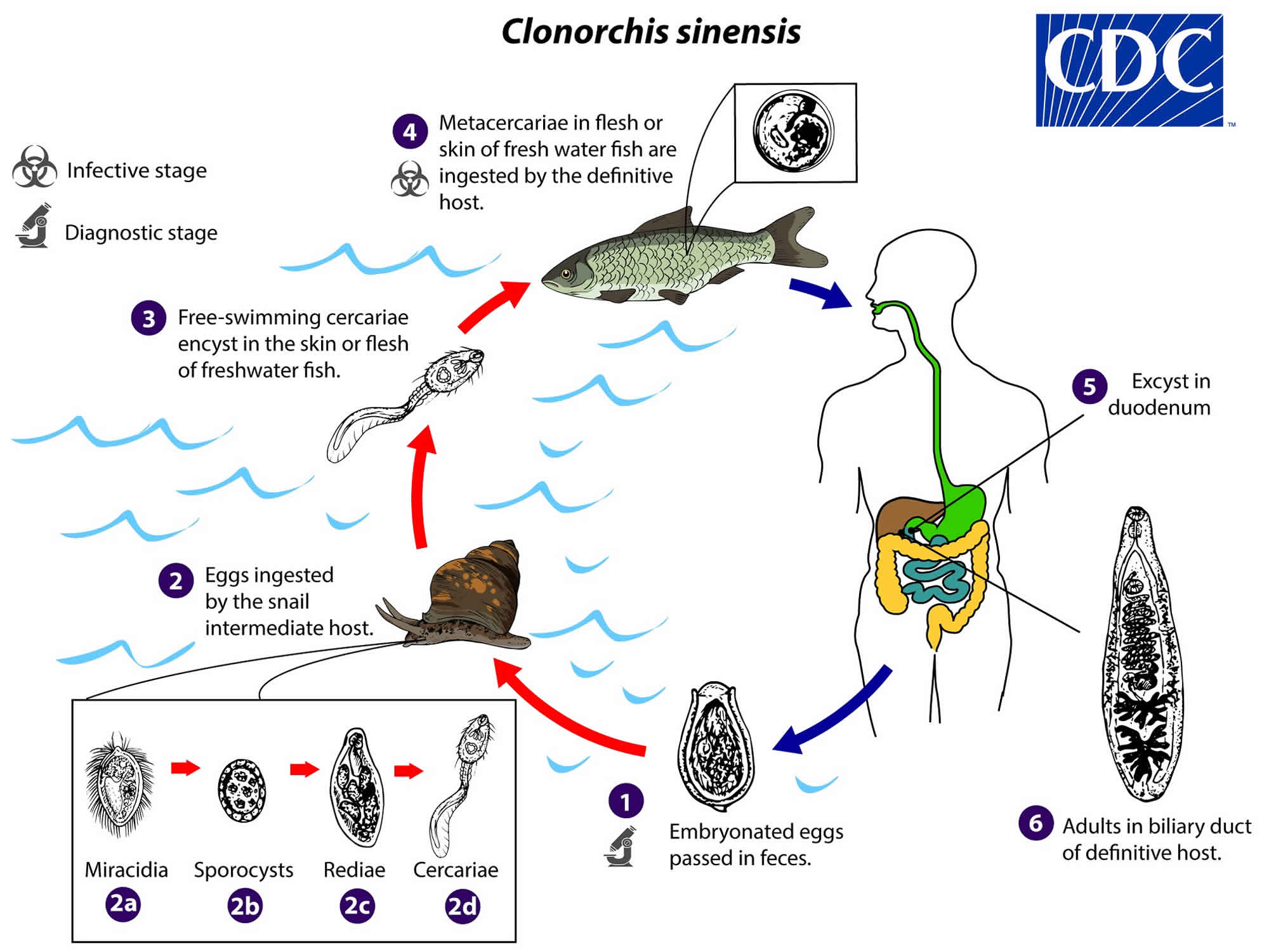

Clonorchis sinensis life cycle

The trematode Clonorchis sinensis (Chinese or oriental liver fluke) is an important foodborne pathogen and cause of liver disease in Asia. Clonorchis sinensis appears to be the only species in the genus involved in human infection.

Clonorchis sinensis eggs are discharged in the biliary ducts and in the stool in an embryonated state (number #1). Eggs are ingested by a suitable snail intermediate host (number #2). Eggs release miracidia (number #2a), which go through several developmental stages [sporocysts (number #2b), rediae (number #2c), and cercariae (number #2d)]. The cercariae are released from the snail and, after a short period of free-swimming time in water, they come in contact and penetrate the flesh of freshwater fish, where they encyst as metacercariae (number #3). Infection of humans occurs by ingestion of undercooked, salted, pickled, or smoked freshwater fish (number #4). After ingestion, the metacercariae excyst in the duodenum (number #5) and ascend the biliary tract through the ampulla of Vater (number #6). Maturation takes approximately one month. The adult flukes (measuring 10 to 25 mm by 3 to 5 mm) reside in small and medium sized biliary ducts.

Figure 1. Clonorchis sinensis life cycle

Clonorchis sinensis transmission

People become infected by eating raw or undercooked freshwater fish containing the Clonorchis larvae. Lightly salted, smoked, or pickled fish may contain infectious parasites. Drinking river water or other nonpotable water will not lead to infection with Clonorchis.

The eggs of Clonorchis are ingested by snails in fresh water. After the eggs hatch, infected snails will release microscopic larvae that can enter freshwater fish. People become infected when eating raw or undercooked fish that contains the larvae. After ingestion, the larvae grow into adult worms and live inside the human bile duct system. The life cycle takes three months to complete in humans. Infected people will then pass eggs in their stool or may cough them up.

Liver fluke infections occur mostly in people living in some areas where the parasites are found. Travelers to Asia who consume raw or poorly cooked fish are at risk for liver fluke infection. Chlonorchis is found in Asian countries including Korea, China, Taiwan, Northern Vietnam, Japan, and Asian Russia. Clonorchis infection has been reported in Asian immigrants in non-endemic areas. Some cases were found in people who had ingested imported freshwater fish (undercooked or pickled) containing parasitic cysts.

Can Clonorchis be transmitted person to person?

No. Clonorchis cannot be directly transmitted from person to person.

Clonorchis sinensis infection prevention

Do not eat raw or undercooked freshwater fish. Lightly salted, smoked, or pickled fish can contain infectious parasites. Drinking river water or other non-potable water will not lead to infection with Clonorchis.

The FDA recommends the following for fish preparation or storage to kill any parasites.

- Cooking: Cook fish adequately (to an internal temperature of at least 145° F [~63° C]).

- Freezing (Fish)

- At -4°F (-20°C) or below for at least 7 days (total time); or

- At -31°F (-35°C) or below until solid, and storing at -31°F (-35°C) or below for at least 15 hours; or

- At -31°F (-35°C) or below until solid and storing at -4°F (-20°C) or below for at least 24 hours.

Clonorchiasis symptoms

Most infected persons have no symptoms. Liver flukes infect the liver, gallbladder, and bile duct in humans. While most infected persons have no symptoms, infections that last a long time can result in severe symptoms and serious illness. Infections are not known to last longer than 25–30 years, the lifespan of the parasite.

In mild cases, symptoms may include indigestion, abdominal pain, diarrhea, or constipation. Most signs and symptoms are related to inflammation and intermittent obstruction of the bile ducts. In severe cases, abdominal pain, nausea, and diarrhea can occur.

Untreated, infection may persist for up to 30 years, the lifespan of the parasite. In infections that last a long time, an enlarged liver and malnutrition may occur. In areas where liver flukes are endemic and a person may have multiple long-standing untreated liver fluke infections, the inflammation of the gallbladder and ducts caused by the parasite has been associated with liver and bile duct cancers, including cholangiocarcinoma. Liver flukes are one of many factors that have been associated with cholangiocarcinoma. Other known risk factors for cholangiocarcinoma include hepatitis B, hepatitis C, alcoholic liver disease and other causes of bile duct inflammation. These risk factors are thought to be more common causes of cholangiocarcinoma in the United States than liver fluke infection. Most patients in Western countries do not have an identifiable risk factor for cholangiocarcinoma.

Clonorchiasis complications

The liver flukes reside within the biliary tree and cause obstruction, inflammatory irritation, and fibrosis, which, when present for an extended time, can eventually lead to cholangiocarcinoma. Cholangiocarcinoma is the most severe and lethal outcome of a burdensome Clonorchis sinensis infection. This will usually present with vague symptoms such as right upper quadrant pain, nausea, vomiting, and obstructive jaundice. The mainstay of treatment for cholangiocarcinoma is surgical resection. The specific required procedure is dependent on the location of the lesion and is discussed more in-depth under the cholangiocarcinoma article 2.

Clonorchis sinensis diagnosis

Ova and parasite (O&P) stool examinations for liver fluke eggs is the only test available for the diagnosis of Clonorchis infection. More than one stool sample may be needed to identify the eggs. The eggs of Clonorchis are very similar to those of Opisthorchis, another liver fluke, but can be distinguished by microscopic features. Stool examination is unlikely to result in a diagnosis in persons whose only exposure to Clonorchis took place more than 25–30 years ago (the life span of a liver fluke), as the liver fluke must be living in order to produce eggs. Additionally, cysts containing the parasite can sometimes be detected by ultrasound, CT, or MRI.

Serologic testing for Clonorchis is not useful for patient management and is not available in the United States. In the absence of detection of liver flukes, there is no test available that can determine if liver fluke infection is the underlying cause of cholangiocarcinoma or other hepatobiliary conditions. Routine screening of asymptomatic individuals with a history of travel to endemic countries for liver fluke infection is not recommended.

Clonorchiasis treatment

Praziquantel or albendazole are the drugs of choice to treat Clonorchis sinensis infection.

- Praziquantel, adults, 75mg/kg/day orally, three doses per day for 2 days; the pediatric dosage is the same. Praziquantel should be taken with liquids during meals.

- Albendazole is an alternative drug; the dosage for adults is 10mg/kg/day for 7 days. The pediatric dosage is the same. Albendazole should be taken with food; a fatty meal increases the bioavailability.

Praziquantel

Treatment in pregnancy

- Pregnancy Category B: Either animal-reproduction studies have not demonstrated a fetal risk but there are no controlled studies in pregnant women or animal-reproduction studies have shown an adverse effect (other than a decrease in fertility) that was not confirmed in controlled studies in women in the first trimester (and there is no evidence of a risk in later trimesters).

- Praziquantel is pregnancy category B. There are no adequate and well-controlled studies in pregnant women. However, the available evidence suggests no difference in adverse birth outcomes in the children of women who were accidentally treated with praziquantel during mass prevention campaigns compared with those who were not. In mass prevention campaigns for which the World Health Organization (WHO) has determined that the benefit of treatment outweighs the risk, WHO encourages the use of praziquantel in any stage of pregnancy. For individual patients in clinical settings, the risk of treatment in pregnant women who are known to have an infection needs to be balanced with the risk of disease progression in the absence of treatment.

Treatment during breastfeeding

- Praziquantel is excreted in low concentrations in human milk. According to WHO guidelines for mass prevention campaigns, the use of praziquantel during lactation is encouraged. For individual patients in clinical settings, praziquantel should be used in breast-feeding women only when the risk to the infant is outweighed by the risk of disease progress in the mother in the absence of treatment.

Treatment in children

- The safety of praziquantel in children aged less than 4 years has not been established. Many children younger than 4 years old have been treated without reported adverse effects in mass prevention campaigns and in studies of schistosomiasis. For individual patients in clinical settings, the risk of treatment of children younger than 4 years old who are known to have an infection needs to be balanced with the risk of disease progression in the absence of treatment.

Albendazole

Treatment in pregnancy

- Albendazole is pregnancy category C. Data on the use of albendazole in pregnant women are limited, though the available evidence suggests no difference in congenital abnormalities in the children of women who were accidentally treated with albendazole during mass prevention campaigns compared with those who were not. In mass prevention campaigns for which the World Health Organization (WHO) has determined that the benefit of treatment outweighs the risk, WHO allows use of albendazole in the 2nd and 3rd trimesters of pregnancy. However, the risk of treatment in pregnant women who are known to have an infection needs to be balanced with the risk of disease progression in the absence of treatment.

Treatment during breastfeeding

- It is not known whether albendazole is excreted in human milk. Albendazole should be used with caution in breastfeeding women.

Treatment in children

- The safety of albendazole in children less than 6 years old is not certain. Studies of the use of albendazole in children as young as one year old suggest that its use is safe. According to WHO guidelines for mass prevention campaigns, albendazole can be used in children as young as 1 year old. Many children less than 6 years old have been treated in these campaigns with albendazole, albeit at a reduced dose.