What is Cowden syndrome

Cowden syndrome is an inherited characterized by multiple noncancerous, tumor-like growths called hamartomas on various parts of the body and an increased risk of developing certain cancers 1. Almost everyone with Cowden syndrome develops hamartomas. These growths are most commonly found on the skin and mucous membranes (such as the lining of the mouth and nose), but they can also occur in the intestine and other parts of the body. The growth of hamartomas on the skin and mucous membranes typically becomes apparent by a person’s late twenties. People with Cowden syndrome usually have large head (macrocephaly), benign tumors of the hair follicle (trichilemmomas), and white papules with a smooth surface in the mouth (papillomatous papules), starting by the late 20s 2. Cowden syndrome is considered part of the PTEN Hamartoma Tumor Syndrome spectrum which also includes Bannayan-Riley-Ruvalcaba syndrome and Proteus syndrome. People who have Cowden syndrome are at an increased risk of developing certain types of cancer, particularly cancers of the breast, a gland in the lower neck called the thyroid, and the lining of the uterus (the endometrium). Other cancers that have been identified in people with Cowden syndrome include colorectal cancer, kidney cancer, and a form of skin cancer called melanoma. Compared with the general population, people with Cowden syndrome develop these cancers at younger ages, often beginning in their thirties or forties. Other diseases of the breast, thyroid, and endometrium are also common in Cowden syndrome. Additional signs and symptoms can include an enlarged head (macrocephaly) and a rare, noncancerous brain tumor called Lhermitte-Duclos disease. A small percentage of affected individuals have delayed development or intellectual disability.

Most Cowden syndrome cases are caused by mutations in the PTEN gene and are inherited in an autosomal dominant manner 3. Although the exact prevalence of Cowden syndrome is unknown, researchers estimate that it affects about 1 in 200,000 people 1.

The features of Cowden syndrome overlap with those of another disorder called Bannayan-Riley-Ruvalcaba syndrome. People with Bannayan-Riley-Ruvalcaba syndrome also develop hamartomas and other noncancerous tumors. Both conditions can be caused by mutations in the PTEN gene. Some people with Cowden syndrome have had relatives diagnosed with Bannayan-Riley-Ruvalcaba syndrome, and other individuals have had the characteristic features of both conditions. Based on these similarities, researchers have proposed that Cowden syndrome and Bannayan-Riley-Ruvalcaba syndrome represent a spectrum of overlapping features known as PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome instead of two distinct conditions.

Some people have some of the characteristic features of Cowden syndrome, particularly the cancers associated with this condition, but do not meet the strict criteria for a diagnosis of Cowden syndrome. These individuals are often described as having Cowden-like syndrome.

Cowden syndrome management typically includes screening for associated tumors and/or prophylactic surgeries 4.

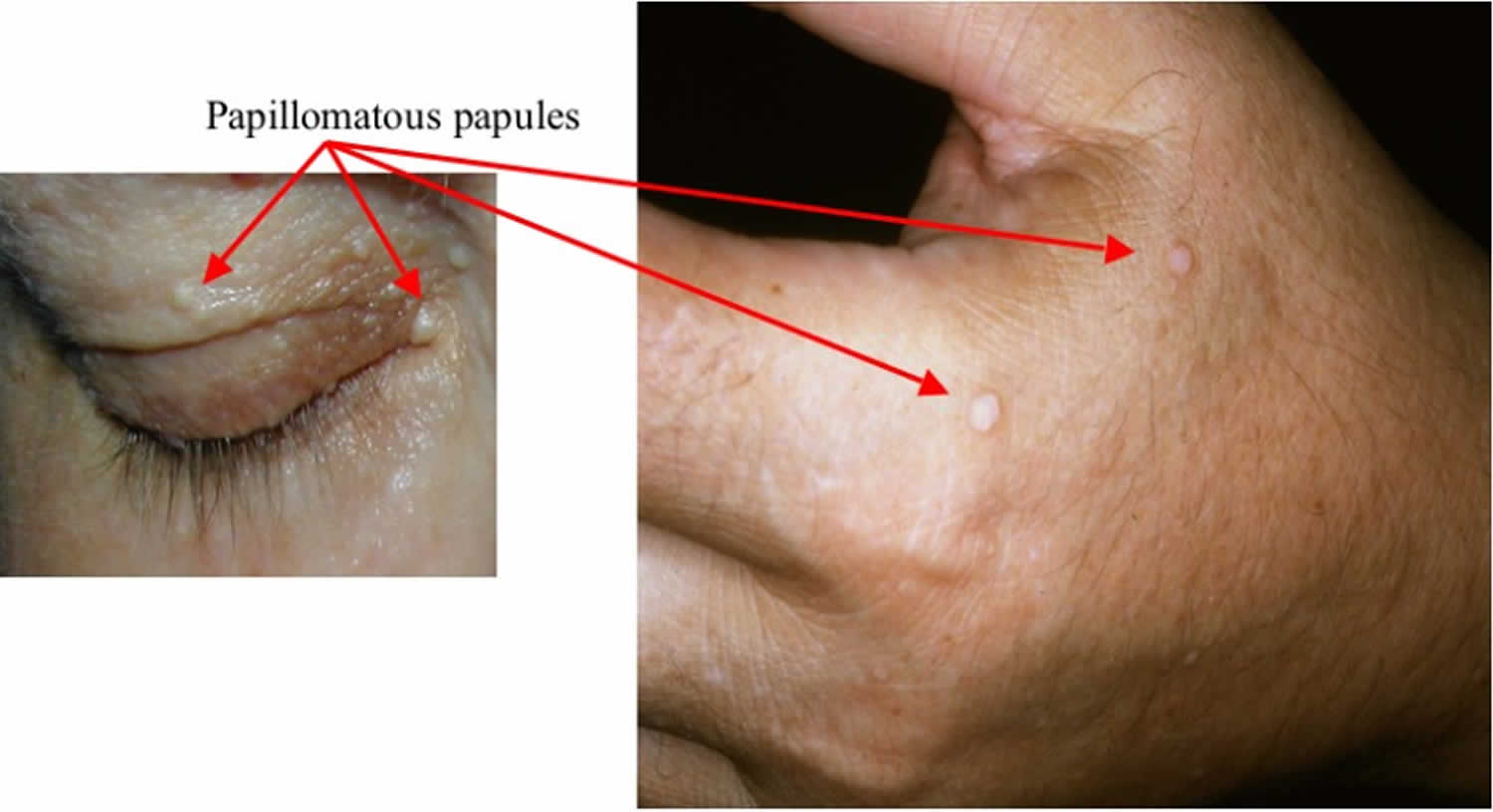

Figure 1. Cowden syndrome

Footnote: (a) From total thyroidectomy surgical scar; (b) trichilemmomas on the face; (c) pigmented verrucoid papules on the dorsum of the hands; (d) oral mucocutaneous papillomatosis; (e) gingival cobblestoning; and (f) palmar keratosis.

[Source 5]What causes Cowden syndrome?

Changes involving at least four genes, PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homolog), SDHB, SDHD, and KLLN, have been identified in people with Cowden syndrome or Cowden-like syndrome 1.

Most cases of Cowden syndrome and a small percentage of cases of Cowden-like syndrome result from mutations in the PTEN gene. The protein produced from the PTEN gene is a tumor suppressor, which means that it normally prevents cells from growing and dividing (proliferating) too rapidly or in an uncontrolled way. Mutations in the PTEN gene prevent the protein from regulating cell proliferation effectively, leading to uncontrolled cell division and the formation of hamartomas and cancerous tumors. The PTEN gene likely has other important functions within cells; however, it is unclear how mutations in this gene cause the other features of Cowden syndrome, such as macrocephaly and intellectual disability.

Other cases of Cowden syndrome and Cowden-like syndrome result from changes involving the KLLN gene. This gene provides instructions for making a protein called killin. Like the protein produced from the PTEN gene, killin probably acts as a tumor suppressor. The genetic change that causes Cowden syndrome and Cowden-like syndrome is known as promoter hypermethylation. The promoter is a region of DNA near the gene that controls gene activity (expression). Hypermethylation occurs when too many small molecules called methyl groups are attached to the promoter region. The extra methyl groups reduce the expression of the KLLN gene, which means that less killin is produced. A reduced amount of killin may allow abnormal cells to survive and proliferate inappropriately, which can lead to the formation of tumors.

A small percentage of people with Cowden syndrome or Cowden-like syndrome have variations in the SDHB or SDHD gene. These genes provide instructions for making parts of an enzyme called succinate dehydrogenase (SDH), which is important for energy production in the cell. This enzyme also plays a role in signaling pathways that regulate cell survival and proliferation. Variations in the SDHB or SDHD gene alter the function of the SDH enzyme. Studies suggest that the defective enzyme may allow cells to grow and divide unchecked, leading to the formation of hamartomas and cancerous tumors. However, researchers are uncertain whether the identified SDHB and SDHD gene variants are directly associated with Cowden syndrome and Cowden-like syndrome. Some of the variants described above have also been identified in people without the features of these conditions.

When Cowden syndrome and Cowden-like syndrome are not related to changes in the PTEN, SDHB, SDHD, or KLLN genes, the cause of the conditions is unknown.

Cowden syndrome inheritance pattern

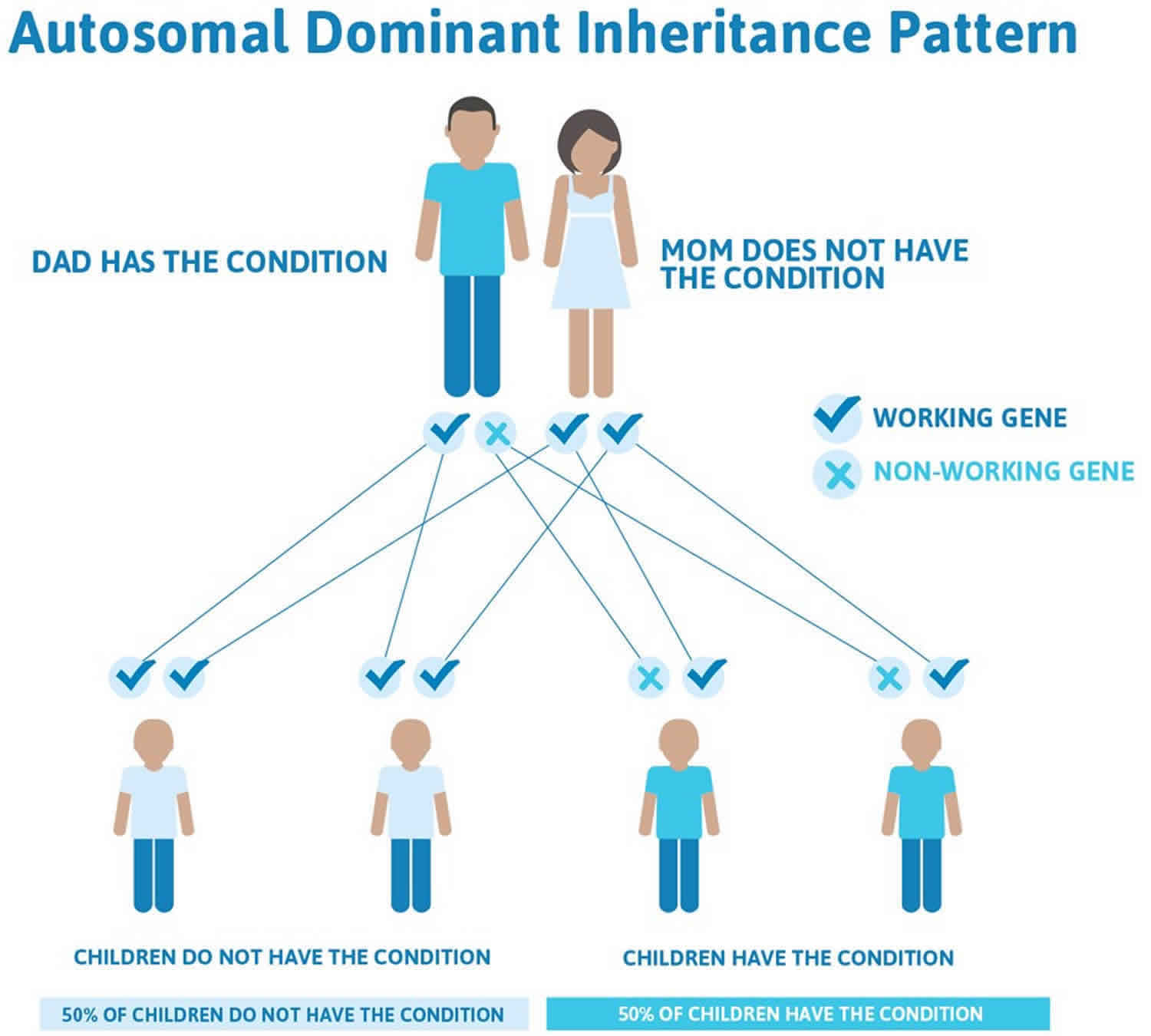

Cowden syndrome and Cowden-like syndrome are inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern, which means one copy of the altered gene in each cell is sufficient to cause the condition and increase the risk of developing cancer. In some cases, an affected person inherits the mutation from one affected parent. Other cases may result from new mutations in the gene. These cases occur in people with no history of the disorder in their family.

Often autosomal dominant conditions can be seen in multiple generations within the family. If one looks back through their family history they notice their mother, grandfather, aunt/uncle, etc., all had the same condition. In cases where the autosomal dominant condition does run in the family, the chance for an affected person to have a child with the same condition is 50% regardless of whether it is a boy or a girl. These possible outcomes occur randomly. The chance remains the same in every pregnancy and is the same for boys and girls.

- When one parent has the abnormal gene, they will pass on either their normal gene or their abnormal gene to their child. Each of their children therefore has a 50% (1 in 2) chance of inheriting the changed gene and being affected by the condition.

- There is also a 50% (1 in 2) chance that a child will inherit the normal copy of the gene. If this happens the child will not be affected by the disorder and cannot pass it on to any of his or her children.

Figure 2. Cowden syndrome autosomal dominant inheritance pattern

People with specific questions about genetic risks or genetic testing for themselves or family members should speak with a genetics professional.

Resources for locating a genetics professional in your community are available online:

- The National Society of Genetic Counselors (https://www.findageneticcounselor.com/) offers a searchable directory of genetic counselors in the United States and Canada. You can search by location, name, area of practice/specialization, and/or ZIP Code.

- The American Board of Genetic Counseling (https://www.abgc.net/about-genetic-counseling/find-a-certified-counselor/) provides a searchable directory of certified genetic counselors worldwide. You can search by practice area, name, organization, or location.

- The Canadian Association of Genetic Counselors (https://www.cagc-accg.ca/index.php?page=225) has a searchable directory of genetic counselors in Canada. You can search by name, distance from an address, province, or services.

- The American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (http://www.acmg.net/ACMG/Genetic_Services_Directory_Search.aspx) has a searchable database of medical genetics clinic services in the United States.

Cowden syndrome symptoms

Cowden syndrome is characterized primarily by multiple, noncancerous growths (called hamartomas) on various parts of the body. Approximately 99% of people who have Cowden syndrome will have benign growths on the skin and/or in the mouth by the end of their 20s. A majority of people with Cowden syndrome will also develop growths (called hamartomatous polyps) along the inner lining of the gastrointestinal tract.

People affected by Cowden syndrome also have an increased risk of developing certain types of cancer. Breast, thyroid, and endometrial (the lining of the uterus) cancers are among the most commonly reported tumors. The lifetime risk of developing breast cancer is 85%; for thyroid cancer the risk is approximately 35%; and the risk for endometrial cancer is about 28%.[1] Other associated cancers include colorectal cancer, kidney cancer, and melanoma. People with Cowden syndrome often develop cancers at earlier ages (before age 50) than people without a hereditary predisposition to cancer 3.

Other signs and symptoms of Cowden syndrome may include benign diseases of the breast, thyroid, and endometrium; a rare, noncancerous brain tumor called Lhermitte-Duclos disease; an enlarged head (macrocephaly); autism spectrum disorder; intellectual disability; and vascular (the body’s network of blood vessels) abnormalities 3.

Cowden syndrome diagnosis

A diagnosis of Cowden syndrome is based on the presence of characteristic signs and symptoms. Genetic testing for a mutation in the PTEN gene can then be ordered to confirm the diagnosis. If a mutation in PTEN is not found, genetic testing for the other genes known to cause Cowden syndrome can be considered 3.

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network 2015 consensus clinical diagnostic criteria have been divided into three categories 6.:

- Pathognomonic criteria (criteria that is characteristic for a particular disease): mucosal and skin lesions

- Major criteria: breast cancer, macrocephaly, thyroid cancer and endometrial cancer

- Minor criteria: thyroid lesions, intellectual disability, hamartomatous intestinal polyps, fibrocystic disease of the breast, lipomas, fibromas, genital and

- urinary tumors or malformations, uterine fibroids

A diagnosis is given if a patient has the “pathognomonic” skin lesions, two or more major criteria, one major and 3 or more minor criteria, or 4 or more minor criteria. The diagnostic criteria for adults and children have some differences 7. The PTEN Cleveland Clinic Risk Calculator can be used to estimate the chance of finding a PTEN mutation in children and adults with signs and symptoms of Cowden syndrome.

Finding mutations in the PTEN gene or other causal genes confirms diagnosis.

Cowden syndrome treatment

Cowden syndrome management and treatment is multidisciplinary and is based on genotype. Once a PTEN germline mutation is identified, surveillance guidelines should be followed. Thyroid ultrasound should begin once a mutation is identified, even under the age of 18. A colonoscopy and biennial renal imaging should begin between the ages of 35-40. Women should perform monthly breast self-examinations and yearly breast screenings as well as transvaginal ultrasounds or endometrial biopsies beginning at the age of 30. Because Cowden syndrome is associated with an increased risk for certain types of cancer, management is typically focused on high-risk cancer screening. According to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network 2018 management guidelines for Cowden disease (multiple hamartoma syndrome), the recommended screening protocol for Cowden syndrome includes 8:

For women, guidelines are as follows:

- Breast awareness starting at age 18 years

- Clinical breast examinations every 6-12 months starting at age 25 years or 5-10 years prior to earliest breast cancer diagnosis in family (whichever comes first)

- Breast screening: (1) Annual mammography and breast MRI screening starting at age 30-35 years or 5-10 years prior to earliest breast cancer diagnosis in family (whichever comes first); (2) Age older than 75 years, management should be considered on an individual basis; (3) For women with a PTEN mutation who are treated for breast cancer, screening of remaining breast tissue with annual mammography and breast MRI should continue

- For endometrial cancer screening, encourage patient education and prompt response to symptoms (ie, abnormal bleeding); consider annual random endometrial biopsies and/or ultrasound beginning at age 30-35 years

- Discuss option of hysterectomy upon completion of childbearing

- Discuss option of risk-reducing mastectomy

- Address psychosocial, social, and quality-of-life aspects of undergoing risk-reducing mastectomy and/or hysterectomy

For men and women, guidelines are as follows:

- Annual history and physical examinations starting at age 18 years or 5 years before the youngest age of diagnosis of a component cancer in the family (whichever comes first), with particular attention to the thyroid examination

- Annual thyroid ultrasound starting at time of Cowden syndrome diagnosis, including in childhood or 5 years before the youngest age of diagnosis of a component cancer in the family (whichever comes first)

- Colonoscopy, starting at age 35 years, unless symptomatic or if close relative with colon cancer before age 40 years, then start 5-10 years before the earliest known cancer in the family; colonoscopy should be performed every 5 years, or more frequently if patient is symptomatic or polyps found

- Consider renal ultrasound starting at age 40 years, then every 1-2 years

- Dermatologic management may be indicated for some patients

- Consider psychomotor assessment in children at diagnosis and brain MRI if there are symptoms

- Education regarding the signs and symptoms of cancer

For risk to relatives, guidelines are as follows:

- Advise about possible inherited cancer risk to relatives, and give options for risk assessment and management

- Recommend genetic counseling and consideration of genetic testing for at-risk relatives

Pediatric (age <18 years)

- Yearly thyroid ultrasound examination (on identification of a PTEN pathogenic variant)

- Yearly skin check with physical examination

- Neurodevelopmental evaluation

If there are not any symptoms, observation alone is prudent. Cutaneous lesions should be removed only if malignancy is suspected or symptoms (e.g., pain, deformity, increased scarring) are serious. When symptomatic, topical agents (e.g., 5-fluorouracil), curettage, cryosurgery, or laser ablation may offer temporary relief 9.

Medical therapy

Systemic therapy with retinoids may temporarily control some of the cutaneous lesions of Cowden disease (multiple hamartoma syndrome); however, recurrence of lesions is typical after treatment is discontinued 10. Topical treatment usually is unsatisfactory.

Rapamycin has shown great promise in both regression of cutaneous lesions and prevention of the development of manifestations of Cowden disease (multiple hamartoma syndrome) in a mouse model with a PTEN deletion. In the mouse model, rapamycin inhibited a key downstream target, mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), which caused rapid regression of Cowden disease (multiple hamartoma syndrome)–like lesions 11. At this time, however, use of rapamycin, should be limited to clinical trials. A clinical trial is currently underway that is studying the effects of rapamycin on syndromes with PTEN mutations.

Surgical Care

Surgical care of facial papules may include the following:

- Chemical peels

- Laser resurfacing

- Surgery and/or shave excisions only if symptomatic or malignancy is suspected because surgical removal may be complicated by recurrence or keloid formation

Cowden syndrome life expectancy

Morbidity and mortality from Cowden disease (multiple hamartoma syndrome) primarily is associated with increased frequency of malignant tumors. Benign tumors that develop in Cowden disease (multiple hamartoma syndrome) patients also can cause significant morbidity. At least 40% of Cowden disease (multiple hamartoma syndrome) patients have a minimum of one malignant primary tumor, although with long-term follow-up care, this number may be higher. Yen et al 12 have reported patients with more than 1 malignancy. Many of the cancers are curable if detected early. Close follow-up care of these patients is necessary. When advanced cancers occur before diagnosis is made, a poor outcome is common.

- Cowden syndrome. https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/condition/cowden-syndrome[↩][↩][↩]

- Cowden syndrome. https://rarediseases.info.nih.gov/diseases/6202/cowden-syndrome[↩]

- Eng C. PTEN Hamartoma Tumor Syndrome. 2001 Nov 29 [Updated 2016 Jun 2]. In: Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, et al., editors. GeneReviews® [Internet]. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 1993-2019. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1488[↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Daly MB & cols. Genetic/Familial High-Risk Assessment: Breast and Ovarian. National Comprehensive Cancer Network.[↩]

- Aslam, A.K., & Coulson, I.H. (2013). Cowden syndrome (multiple hamartoma syndrome). Clinical and experimental dermatology, 38 8, 957-9[↩]

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Genetic/Familial High-Risk Assessment: Breast and Ovarian. Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. 2015[↩]

- Cowden syndrome. https://www.orpha.net/consor/cgi-bin/Disease_Search.php?lng=EN&data_id=243[↩]

- Cowden Disease (Multiple Hamartoma Syndrome) Guidelines. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1093383-guidelines[↩]

- Hildenbrand C, Burgdorf WH, Lautenschlager S. Cowden syndrome-diagnostic skin signs. Dermatology. 2001;202:362–6.[↩]

- Cnudde F, Boulard F, Muller P, Chevallier J, Teron-Abou B. [Cowden disease: treatment with acitretine]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1996. 123(11):739-41.[↩]

- Squarize CH, Castilho RM, Gutkind JS. Chemoprevention and treatment of experimental Cowden’s disease by mTOR inhibition with rapamycin. Cancer Res. 2008 Sep 1. 68(17):7066-72.[↩]

- Yen BC, Kahn H, Schiller AL, Klein MJ, Phelps RG, Lebwohl MG. Multiple hamartoma syndrome with osteosarcoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1993 Dec. 117(12):1252-4.[↩]