Upper cross syndrome

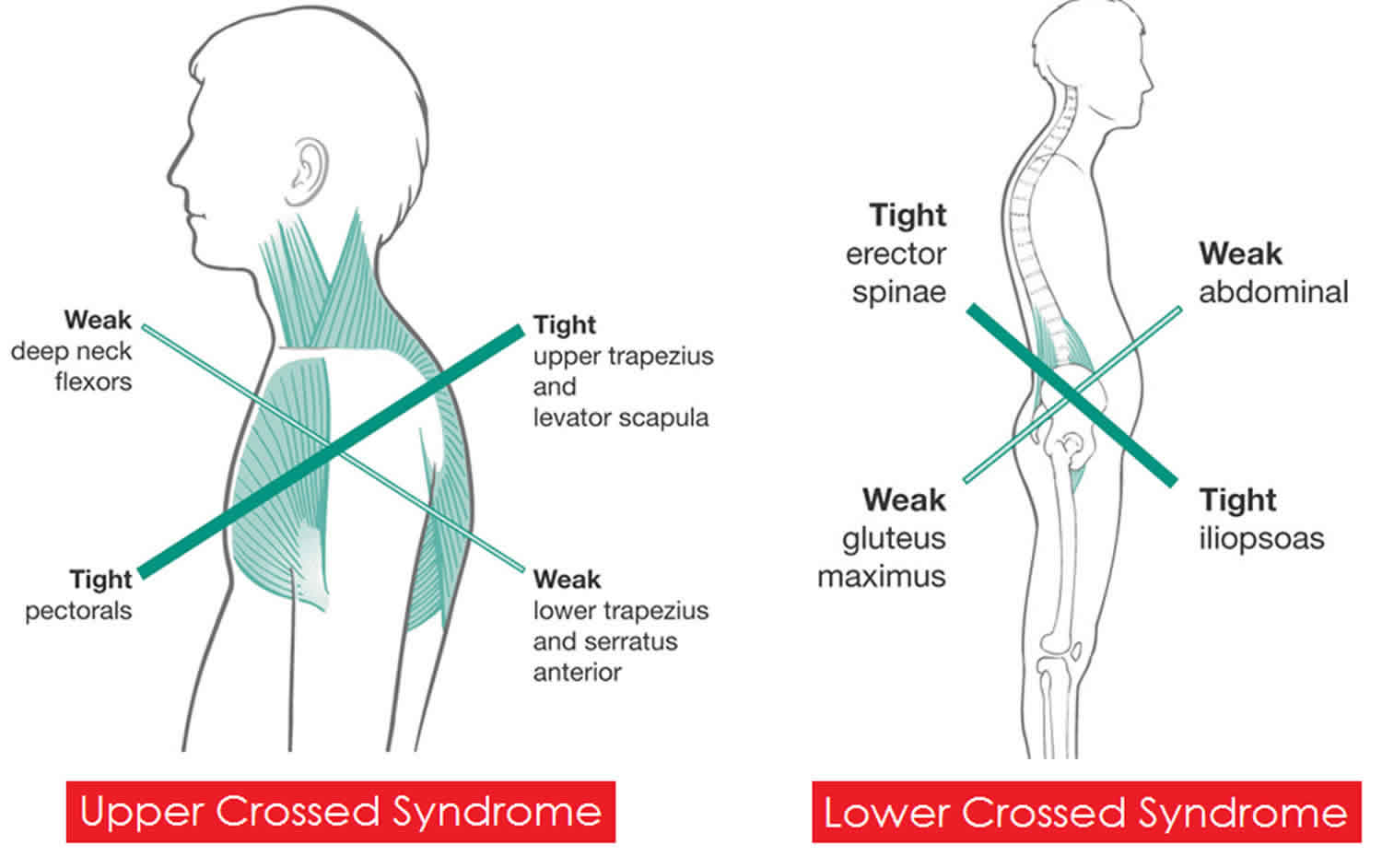

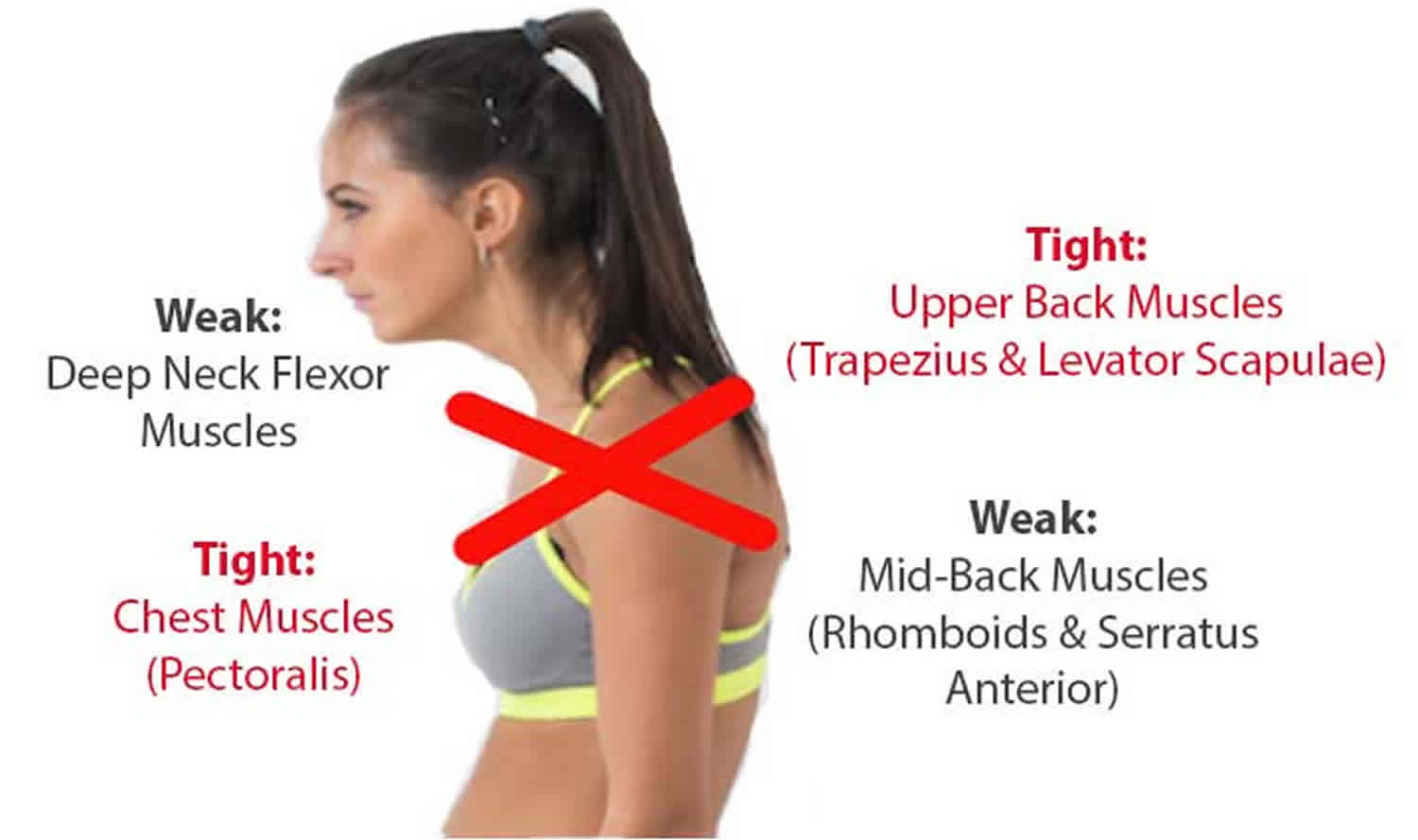

Upper cross syndrome occurs when the muscles in the neck, shoulders, and chest become deformed, usually as a result of poor posture. Upper crossed syndrome is caused by weak lower and middle trapezius, tight upper trapezius and levator scapulae, weak deep-neck flexors, tight suboccipital muscles and sternocleidomastoid, weak serratus anterior, and tight pectoralis major and minor 1. Upper crossed syndrome is caused by muscular imbalance that usually develops between tonic and weak muscles 2. The muscles that are typically the most affected are the upper trapezius and the levator scapula, which are the back muscles of the shoulders and neck. First, they become extremely strained and overactive. Then, the muscles in the front of the chest, called the major and minor pectoralis, become tight and shortened. When these muscles are overactive, the surrounding counter muscles are underused and become weak. The overactive muscles and underactive muscles can then overlap, causing an X shape to develop. Individuals who present with upper crossed syndrome will show a forward head-and-neck posture 3.

There are two types of muscles present in your body – the postural muscles such as pectoralis major, upper trapezius, and sternocleidomastoid and other phasic muscles such as deep-neck flexors, and lower trapezius 3. Predominantly static or postural muscles have a tendency to tighten. In various movements, they are activated more than the muscles that are predominantly dynamic and phasic in function, which have a tendency to develop weakness 4. Opposite group muscle imbalances in upper crossed syndrome give rise to postural disturbance 5.

Individuals who present with upper crossed syndrome will show a forward head posture, hunching of the thoracic spine (rounded upper back), elevated and protracted shoulders, scapular winging, and decreased mobility of the thoracic spine 6. Sometimes, manual material handling activities can cause musculoskeletal disorders 7, for example, the workers who do their work in inappropriate position and repeating the same action throughout their workday 8.

The simultaneous occurrence of forward head posture and rounded shoulder is nothing but upper crossed syndrome 9. Musculoskeletal injuries often affect both neck and upper limbs and can occur when performing a given professional activity that is repetitive and involves still posture as well as handling considerable load 10. Forward head posture is caused by maintaining an abnormal or inappropriate posture for a long time 11. Studies prove that causes of bad posture can be the occupation related; continuous working for long hours may result in postural defects and deviation 12.

Upper cross syndrome is usually a preventable condition. Practising proper posture is of vital importance in both preventing and treating the condition. Be aware of your posture and correct it if you find yourself adopting the wrong position.

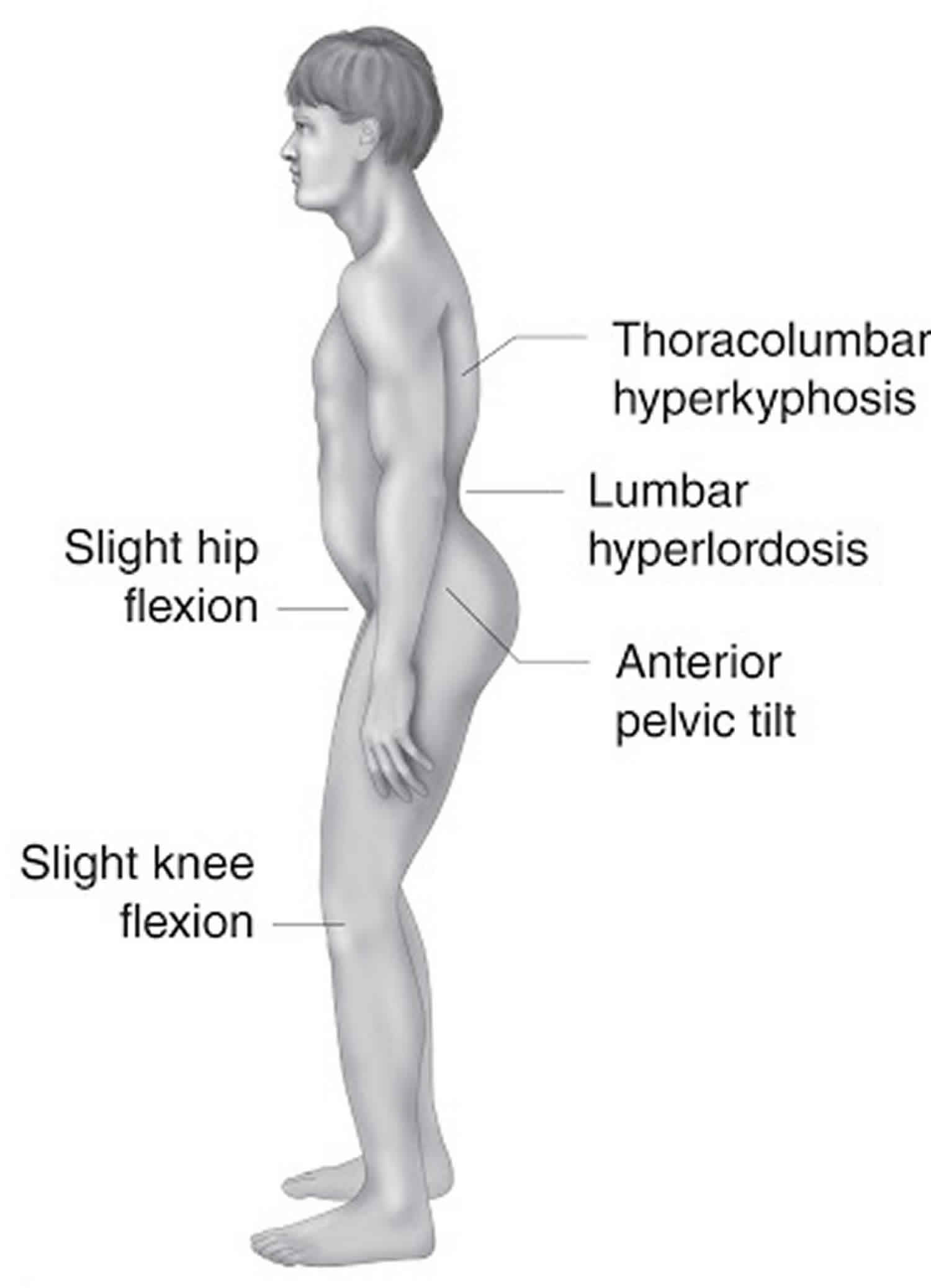

Figure 1. Upper cross syndrome

Upper cross syndrome causes

Most cases of upper cross syndrome arise because of continual poor posture. Specifically, standing or sitting for long periods with the head pushed forward.

People often adopt this position when they are:

- reading

- watching TV

- biking

- driving

- using a laptop, computer, or smartphone

In a small number of cases, upper cross syndrome can develop as the result of congenital defects or injuries.

Upper cross syndrome symptoms

People with upper cross syndrome display stooped, rounded shoulders and a bent-forward neck. The deformed muscles put strain on the surrounding joints, bones, muscles and tendons. This causes most people to experience symptoms such as:

- neck pain

- headache

- weakness in the front of the neck

- strain in the back of the neck

- pain in the upper back and shoulders

- tightness and pain in the chest

- jaw pain

- fatigue

- lower back pain

- trouble with sitting to read or watch TV

- trouble driving for long periods

- restricted movement in the neck and shoulders

- pain and reduced movement in the ribs

- pain, numbness, and tingling in the upper arms.

Upper cross syndrome diagnosis

Upper cross syndrome has a number of identifying characteristics that will be recognized by your physical therapist or doctor. These include:

- the head often being in a forward position

- the spine curving inward at the neck

- the spine curving outward at the upper back and shoulders

- rounded, protracted, or elevated shoulders

- the visible area of the shoulder blade sitting out instead of laying flat

If these physical characteristics are present and you are also experiencing the symptoms of upper cross syndrome, then your physical therapist or doctor will diagnose the condition.

Upper cross syndrome treatment

The treatment options for upper cross syndrome are chiropractic care, physical therapy and exercise. Usually a combination of all three is recommended.

Chiropractic care

The tight muscles and poor posture that produce upper cross syndrome can cause your joints to become misaligned. A chiropractic adjustment from a licensed practitioner can help to realign these joints. This can increase range of motion in the affected areas. An adjustment also usually stretches and relaxes the shortened muscles.

Physical therapy

A physical therapist uses a combination of approaches. First, they offer education and advice related to your condition, such as why it’s occurred and how to prevent it in the future. They will demonstrate and practise exercises with you that you will need to continue with at home. They also use manual therapy, where they use their hands to relieve pain and stiffness and encourage better movement of the body.

Upper cross syndrome stretches

Lying down exercises

- Lay flat on the ground with a thick pillow placed about a third of the way up your back in alignment with your spine.

- Let your arms and shoulders roll out and your legs fall open in a natural position.

- Your head should be neutral and not feel stretched or strained. If it does, use a pillow for support.

- Stay in this position for 10–15 minutes and repeat this exercise several times per day.

Sitting down exercises

- Sit with your back straight, place your feet flat on the floor and bend your knees.

- Put your palms flat on the ground behind your hips and rotate your shoulders backward and down.

- Stay in this position for 3–5 minutes and repeat the exercise as many times as you can throughout the day.

Lower cross syndrome

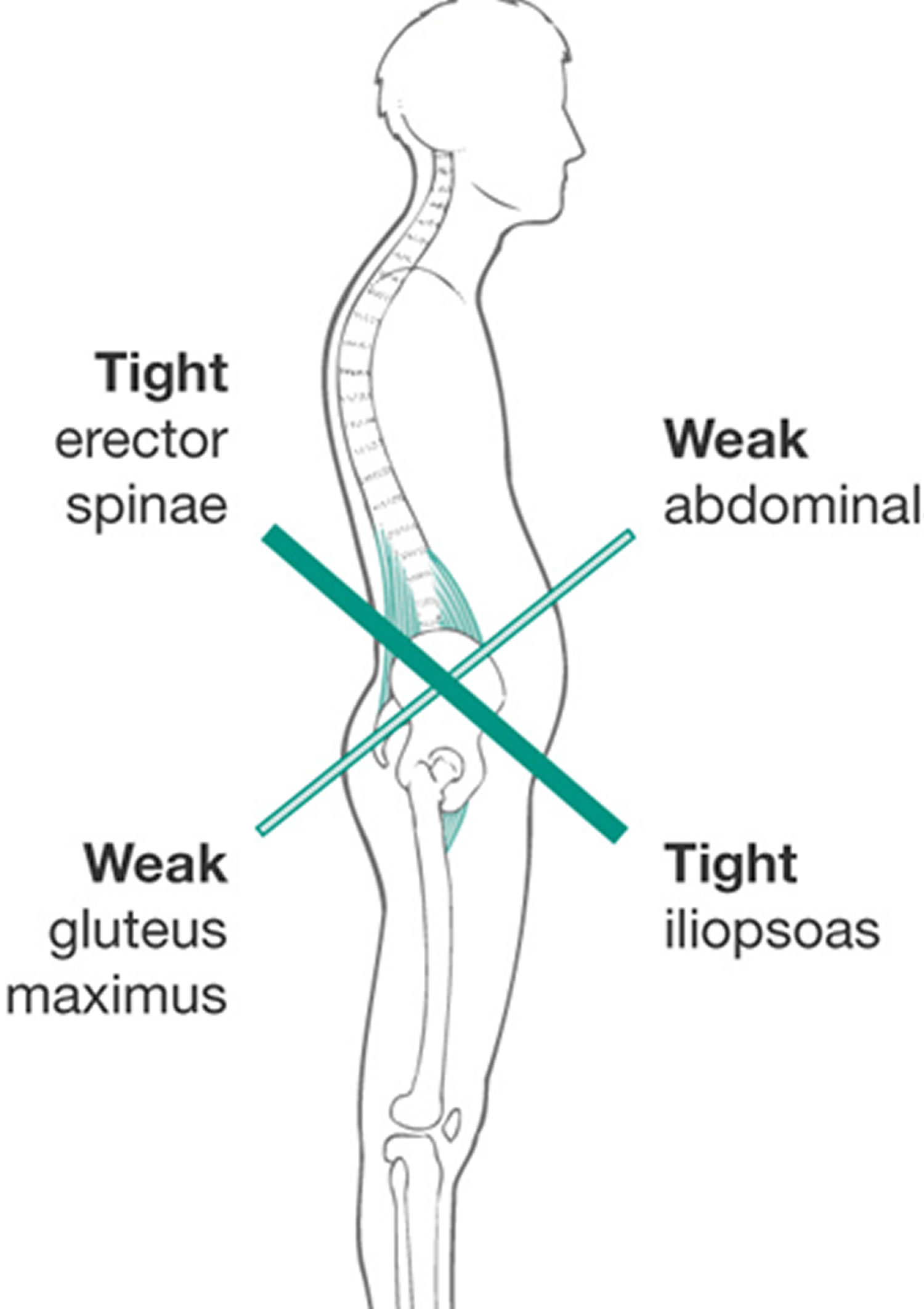

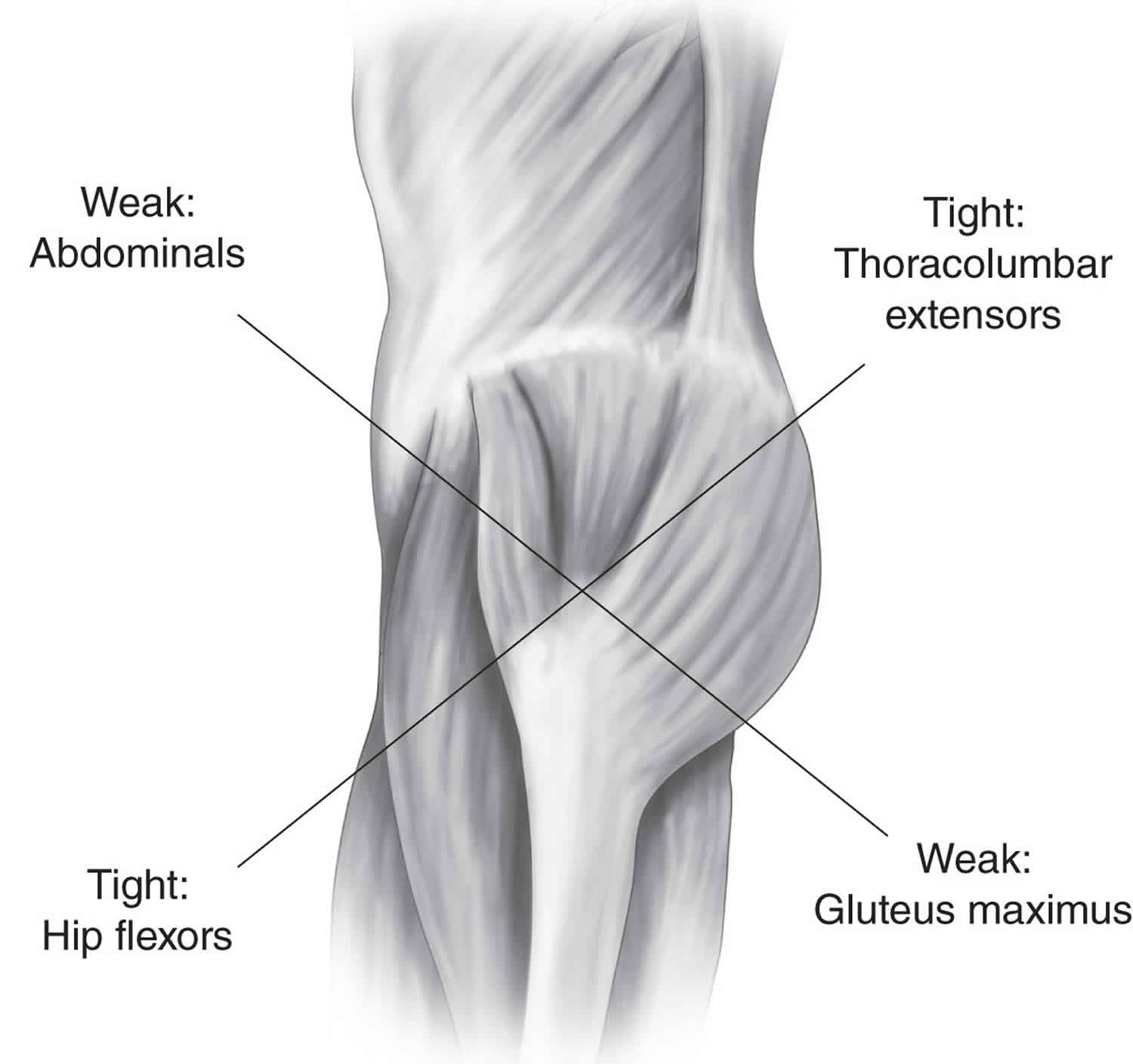

Lower cross syndrome also called Unterkreuz syndrome, pelvic crossed syndrome or distal crossed syndrome, is a neuromuscular condition in which there are tight and weak muscles. The lower cross syndrome is the result of muscle strength imbalances in the lower portion of the body. These imbalances can occur when muscles are constantly shortened or lengthened in relation to each other. The involved tight muscles are the thoracolumbar extensors and hip flexors, while the weak muscles are the abdominals and gluteus maximus. The ‘cross’ is due to a combination of tight muscles and weak muscles, which from a side view are seen as an X. Some people also experience upper cross syndrome at the same time.

The muscles involved with lower cross syndrome are:

- weak: abdominals and gluteus maximus

- tight: thoracolumbar extensors (erector spinae) and hip flexors (iliopsoas)

The lower cross syndrome is characterized by specific patterns of muscle weakness and tightness that cross between the dorsal and the ventral sides of the body. In lower cross syndrome there is overactivity and hence tightness of hip flexors and lumbar extensors. Along with this there is underactivity and weakness of the deep abdominal muscles on the ventral side and of the gluteus maximus and medius on the dorsal side 13. The hamstrings are frequently found to be tight in lower cross syndrome as well. This imbalance results in an anterior tilt of the pelvis, increased flexion of the hips, and a compensatory hyperlordosis in the lumbar spine.

Lower cross syndrome involves weakness of the trunk muscles: rectus abdominus, obliques internus abdominis, obliques externus abdominis and transversus abdominis, along with the weakness of the gluteal muscles: gluteus maximus, gluteus medius and gluteus minimus. These muscles are inhibited and substituted by activation of the superficial muscles.

There is co-existing over activity and tightness of the thoracolumbar extensors: erector spinae, multifidus, quadratus lumborum and latissimus dorsi; and that of the hip flexors: iliopsoas and tensor fasciae latae.

The hamstrings compensate for anterior pelvic tilt or an inhibited gluteus maximus.

Here is a picture to better depict why it is called lower cross syndrome.

Figure 2. Lower cross syndrome

Lower cross syndrome symptoms

This muscle imbalance creates joint dysfunction (ligamentous strain and increased pressure particularly at the L4-L5 and L5-S1 segments, the sacroiliac joint and the hip joint), joint pain (lower back, hip and knee) and specific postural changes such as: anterior pelvic tilt, increased lumbar lordosis, lateral lumbar shift, external rotation of hip and knee hyperextension. It also can lead to changes in posture in other parts of the body, such as: increased thoracic kyphosis and increased cervical lordosis 14.

There are two known subtypes of lower cross syndrome, A and B lower cross syndrome. The two types are similar and involve the same main muscle imbalance characteristics. For type A the imbalance manifests mainly in the hip, while for type B the imbalance mainly manifests in the lower back. The two subgroups can be distinguished based upon the altered postural alignment and also changed regional myofascial activation patterns. An observation of the lower pole of the thorax and the anterolateral abdominal wall shows whether there are problems with the activity level and balance between the diaphragm and transversus abdominis. Mostly, there is an underactivity of the deep transversus associated with either increased or decreased superficial activity in the obliques and rectus 14.

Type A lower cross syndrome

Type A lower cross syndrome is also called “the posterior pelvic crossed syndrome”. In this subgroup there is a domination of the axial extensor 14. Because the hip flexors are shortened, the pelvis is tilted anteriorly and the hip and knee are in slight flexion. Associated with this is an anterior translation of the thorax because of an increased thoraco-lumbar extensor activity. This gives an expression for the compensatory hyperlordosis of the lumbar spine and hyperkyphosis in the transition from thoracic to lumbar spine. This leads to a decrease in the quality of breathing and of the postural control. Above that the entire thorax will move up, due to the minimal inferior stabilization created by the abdominals. The infra-sternal angle will go up to more than 90° and the postero-inferior thorax will be hyper-stabilized through which it will cause a limited postero-lateral costo-vertebral movement 14.

The more anterior and elevated position of the thorax will disturb the stabilization synergies of the Lower Pelvic Unit. The patient will lift the thorax during inspiration which causes an upper chest breathing pattern. This means that the active exhalation will be difficult, because the abdominal activation fails to bring the thorax down and back into the more expiratory caudal (or neutral) position. The abdominal activation is also not sufficient to create the essential intra abdominal pressure. We will notice that the expiratory phase is shortened. This problem arises when the coordination and co-activation between the transverses and the diaphragm is missing. The patient is forced to use the Central Posterior Clinch behavior, which results in an overactivity of the psoas 14.

Figure 3. Type A lower cross syndrome

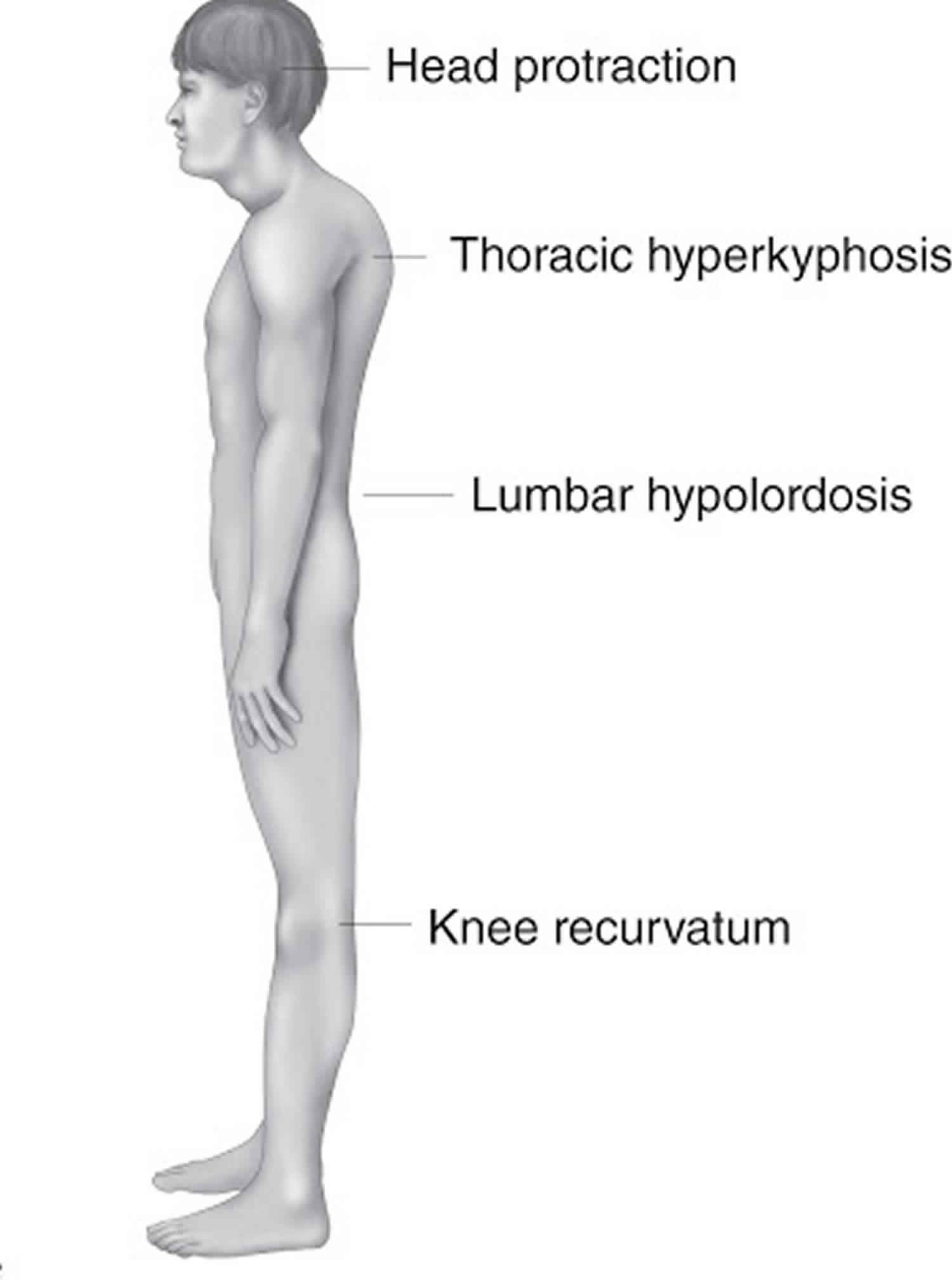

Type B lower cross syndrome

Type B lower cross syndrome is also called “the anterior pelvic crossed syndrome”. In this type the abdominal muscles are too weak and too short. This is associated with a predominant tendency of the axial flexor activity 14. The compensation is reflected by a minimal hypolordosis of the lumbar spine, a hyperkyphosis of the thoracic spine and protraction of the head. The pelvis is postured more anteriorly and the knees are in hyperextension 15.

Figure 4. Type B lower cross syndrome

Lower cross syndrome diagnosis

Examination for lower cross syndrome should follow the same patterns as for examining a patient for low back pain.

Some specific examination points for lower cross syndrome include the following:

- Observation in erect standing and gait

- Position of the pelvis. There is usually an increase of anterior tilt of the pelvis. This can be associated with increased lumbar lordosis.

- Next the shape, size and tone of the tightened/inhibited muscles.

- Active examination 16:

- Hip extension – is examined to analyze the hyperextension phase of the hip in gait. Use straight leg lifting.

- Hip abduction –the patient with lower cross syndrome, will combine the abduction with an lateral rotation and a flexion of the hip.

- Trunk curl up – is tested to estimate the interplay between usually strong iliopsoas and the abdominal muscles.

- Passive examination 16:

- Hip flexors are tested with the patient in a modified Thomas position. This test can be influenced by the stretch of the joint capsule and thus more specific test should be performed to confirm the tightness of the adductors. Confirmation of tightness is clear when excessive soft tissue resistance and decreased range of motion are encountered on application of pressure.

- The tightness of Hamstrings is tested with a straight leg test.

- Thigh adductors are tested with the patient lying supine at the edge of the plinth. Tight hamstrings may contribute to the range limitation. If this situation occurs, bending the knee should increase the range of movement.

- The piriformis muscle is tested with the patient in a supine position. If the muscle is tight, the end feel is hard and may be associated with pain deep in the buttocks.

- Quadratus lumborum is difficult to examine. In principle, passive trunk side bending is tested while the patient assumes a side-lying position. The reference point is the level of inferior angle of the scapula. A simpler screening test entails observation of the spinal curve during active lateral flexion of the trunk.

- Spinal erectors are also difficult to examine. As a screening test, forward bending in a short sit allows observation of the gradual curvature of the spine.

- Triceps surae are tested by performing passive dorsiflexion of the foot. Normally, the therapist should be able to achieve passive dorsiflexion to 90 degrees.

Lower cross syndrome treatment

A tight muscle should be stretched efficiently. Stretching of tight muscles results in improved strength of inhibited antagonistic muscles, probably mediated via the Sherrington’s law of reciprocal innervation 17.

This may involve purely soft tissue approaches. Stretch the specific muscle for a duration of 15 seconds. A five week active stretching program significantly increases active and passive ROM in the lower extremity 17.

The solution for these common patterns is to identify both the shortened and the weakened structures and to set about normalizing their dysfunctional status. This might involve:

- Deactivating trigger points and removing muscular adhesions. Perform myofascial release and trigger-point massage to the gluteus muscles, iliopsoas and tensor fasciae latae 18.

- Laser or ultrasound therapy on the gluteus medius and tensor fasciae latae.

- Regaining the normal lumbar flexion mobility

- Core stabilization exercises to strengthen the abdominal muscles.

- Re-education of posture and body usage. It is necessary to relearn the specific activiation of every element within the Lower Pelvic Unit. This will establish the important fundamental patterns of intra-pevlic control and will also integrate these patterns into basis functional patterns of movement control iniated from the pelvis.

- Retraining patients with Posterior Pelvic Crossed Syndrome

- It is important to improve the active exhalation, which will bring the thorax caudally on a stable pelvis. It is important to assist the patient, while maintaining the neutral position.. While executing this exercise, it is crucial that the patient breaths down and not up. The patient has to be able to create sufficient intra-abdominal pressure , while maintaining a regular breathing pattern.

- The patient has to lie down on his back, in supine supported hip flexion to eliminate gravity. The therapist asks the patient to ‘breathe down to the lower placed hand’. It is then important to encourage an active and long exhalation. This gives the patient the sense of the required action. When the correct pattern is mastered it can be progressed into unsupported hip flexion. It is important to push the ribs wide and back, without lifting the thorax. To realize this, the client is asked to push out sideways into the hands of the therapist 19.

Iliopsoas stretch (and rectus femoris) 20.

The patient is placed in Thomas position. The not-stretched side is maximally flexed to stabilize the pelvis and flatten the lumbar spine. The other leg is normally in flexed position because of the tightness of the iliopsoas. Push this leg into the neutral position (onto the table). Hold this position 15 seconds.

If you want to integrate the rectus femoris into this stretch, bend the knee more than 90° while performing the iliopsoas stretch.

Figure 5. Iliopsoas stretch

Erector spinae stretch 20.

The patient lies supine in the fetal position, their knees to their chest with their arms wrapped around their knees. Exhale and stretch. Hold this position for 15 seconds.

Figure 6. Erector spinae stretch

- Muscolino J. Upper crossed syndrome. J Aust Tradit Med Soc. 2015;21:80–5.[↩]

- Yoo WG, Yi CH, Kim MH. Effects of a ball-backrest chair on the muscles associated with upper crossed syndrome when working at a VDT. Work. 2007;29:239–44.[↩]

- Mujawar JC, Sagar JH. Prevalence of Upper Cross Syndrome in Laundry Workers. Indian J Occup Environ Med. 2019;23(1):54–56. doi:10.4103/ijoem.IJOEM_169_18 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6477943[↩][↩]

- Weon JH, Oh JS, Cynn HS, Kim YW, Kwon OY, Yi CH, et al. Influence of forward head posture on scapular upward rotators during isometric shoulder flexion. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2010;14:367–74.[↩]

- Evans O, Patterson K. Predictors of neck and shoulder pain in non-secretarial computer users. Int J Ind Ergon. 2000;26:357–65.[↩]

- Introduction to the Ergonomics of Manual Material Handling. Diunduhdari: Diakses Tanggal Maret; 2012. Public Education Section Department of Business and Consumer Business Oregon OSHA.[↩]

- Etika M, Indah P, Rafsanjan F. Jurnal Ilmiah Teknik Industri. 5. Vol. 5. Diunduhdari: Diakses Tanggal; 2006. Analisis Manual Material Handling Menggunakan Niosh Equation. 4 Maret 2014.[↩]

- Janda V. Muscles and Motor Control in Cervicogenic Disorders. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1994.[↩]

- Buckle PW, Devereux JJ. The nature of work-related neck and upper limb musculoskeletal disorders. Appl Ergon. 2002;33:207–17.[↩]

- Neuman DA. Kinesiology of the Musculoskeletal System. 2nd ed. Singapore: Mosby; 2009.[↩]

- Kumar B. Poor posture and its causes. Int J Phys Educ Sports Health. 2016;3:177–8.[↩]

- Kaushik V, Charpe NA. Effect of body posture on stress experienced by worker. Stud Home Comm Sci. 2008;2:1–5.[↩]

- Key J. The Pelvic Crossed Syndromes: A reflection of imbalanced function in the myofascial envelope; a further exploration of Janda’s work. Journal of bodywork and movement therapies. 2010 July;14:299-301[↩]

- Ishida, H., Hirose, R., Watanabe, S., 2012. Comparison of changes in the contraction of the lateral abdominal muscles between the abdominal drawing-in maneuver and breathe held at the maximum expiratory level. Man. Ther. 17 (5), 427- 431.[↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Chaitow L., DeLany J.W., (2002). Clinical application of neuromuscular techniques: the lower body: Churchill livingstone. (p.26,36).[↩]

- Liebenson C. Rehabilitation of the Spine: A Practioner’s Manaul. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007.[↩][↩]

- Roberts, J., & Wilson, K. (1999). Effect of stretching duration on active and passive range of motion in the lower extremity. Br J Sports Med , 259-263.[↩][↩]

- Simons D.G., Understanding Effective Treatments of Myofascial Trigger Points: Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies, 2002, Volume 6, issue 2.[↩]

- Key J. (2013), ‘The core’: Understanding it, and retraining its dysfunction, Journal of Bodywork; Movement Therapies 17, p. 541- 559[↩]

- Liebenson, C. (2007). Evaluation of Muscular Imbalance. In Rehabilitation of the Spine: A Practitioner’s Manual (p. 209). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.[↩][↩]