Cutaneous porphyria tarda

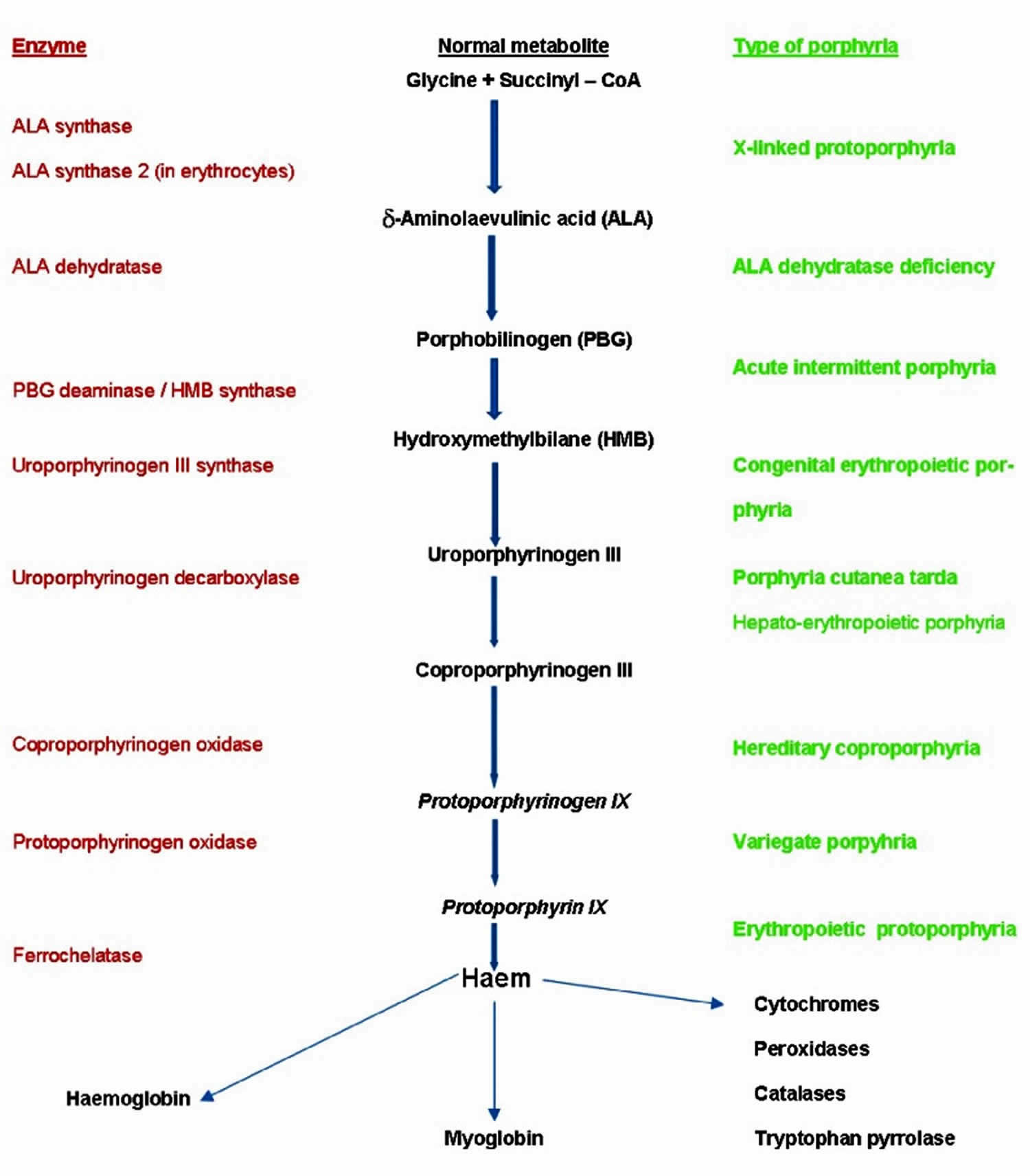

Porphyria cutanea tarda is the most common type of porphyria. The porphyrias are a group of rare metabolic disorders caused by inherited or acquired enzyme defects in the heme biosynthesis metabolic pathway ( Figure 1) 1. All the porphyrias except acute intermittent porphyria and the exceptionally rare aminolevulinic acid (ALA) dehydratase deficiency porphyria (Doss porphyria) can affect the skin 2. Historically, porphyrias have been subdivided into hepatic and erythropoietic forms, according to the site of expression of the dysfunctional enzyme 1. However, in a clinical approach, it is much more convenient to classify porphyria according to their clinical manifestations—as acute (neurovisceral) versus non-acute (cutaneous) porphyrias 3. In some of the acute porphyria types both neurovisceral and cutaneous symptoms may be present. The acute neurovisceral forms are characterized by overproduction of delta-aminolevulinic acid (ALA) and porphobilinogen, which are porphyrin precursors, at the initial steps of heme synthesis 4, while the cutaneous porphyrias are characterized by accumulation of porphyrins, which are the precursors at the final steps of the synthesis 5. This fundamental difference is the basis of the different clinical symptoms.

Cutaneous porphyrias important general points are that (1) they are a diverse group of conditions, all showing skin diseases strictly limited to sun-exposed skin areas with a predilection for the backs of the hands and the face, and are due to a problem in the haem biosynthetic pathway—so certain types of cutaneous porphyria rather than ‘cutaneous porphyria’ should be part of a differential diagnosis list—(2) it is visible light (not ultraviolet) that is relevant, and (3) all the cutaneous porphyrias can also be associated with complicating diseases in organs other than the skin 2. Two of the blistering (usually bullae, large blisters) and fragility (variegate porphyria and hereditary coproporphyria) porphyrias can also cause acute porphyria attacks. Acquired porphyria cutaneous tarda is the one porphyria that is not primarily inherited but is a consequence of chronic liver inflammation and liver iron overload. Erythropoietic protoporphyria can affect the biliary system and rarely the liver and is frequently associated with a mild anemia.

All the cutaneous porphyrias can have (either as a consequence of the porphyria or as part of the cause of the porphyria) involvement of other organs as well as the skin 2. The single commonest cutaneous porphyria in most parts of the world is acquired porphyria cutanea tarda (porphyria cutanea tarda type 1), which is usually due to chronic liver disease and liver iron overload 2. The next most common cutaneous porphyria is erythropoietic protoporphyria, is an inherited disorder in which the accumulation of bile-excreted protoporphyrin can cause gallstones and, rarely, liver disease. Some of the porphyrias that cause blistering (usually bullae) and fragility (clinically and histologically identical to porphyria cutanea tarda) can also be associated with acute neurovisceral porphyria attacks, particularly variegate porphyria and hereditary coproporphyria.

Management of porphyria cutanea tarda mainly consists of visible-light photoprotection measures while awaiting the effects of treating the underlying liver disease (if possible) and treatments to reduce serum iron and porphyrin levels. In erythropoietic protoporphyria, the underlying cause can be resolved only with a bone marrow transplant (which is rarely justifiable in this condition), so management consists particularly of visible-light photoprotection and, in some countries, narrowband ultraviolet B phototherapy. Afamelanotide is a promising and newly available treatment for erythropoietic protoporphyria and has been approved in Europe since 2014. Porphyria cutanea tarda increases the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with chronic liver disease 6.

Figure 1. Heme Synthesis Pathway – enzymes involved in the pathway and the associated porphyrias with the disruption of each specific enzyme

Footnote: Simplified porphyria–haem biosynthetic pathway illustrating the enzyme defects (decreased activity for all except aminolevulinic acid (ALA) synthase 2 with which increased activity causes X-linked protoporphyria) involved in the main porphyrias.

[Source 2 ]Figure 2. Porphyria cutanea tarda

Cutaneous porphyria causes

The cutaneous porphyria or porphyrias affecting the skin can be divided into (1) those that present mainly with visible light–exposed site bullae and fragility (most commonly porphyria cutanea tarda), (2) those, particularly erythropoietic protoporphyria, that present with neuropathic-type pain, edema, erythema, and lesions on exposed sites (acute phototoxic porphyria), and (3) the extremely rare, severe, and mutilating porphyrias such as congenital erythropoietic porphyria (Günther’s disease) 2. There are various classification schemes, but if the porphyrias are considered from the point of view of the clinical cutaneous features, this is now one of many porphyria classification schemes 1, 2, along with considerations of where in the body overproduction of porphyrin intermediates occurs (hepatic or erythropoietic) and whether it is mainly a neurovisceral attack porphyria or a cutaneous porphyria or where (which country) it was first described in detail (such as South African porphyria and Swedish porphyria).

Porphyria cutaneous tarda is due to a defective enzyme in the liver (uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase). This is involved in synthesis of the red pigment in blood cells (haem). Some families carry an enzyme that is prone to oxidation under certain circumstances, most often due to iron accumulation.

There are basically two forms of porphyria cutaneous tarda, type 1 and type 2.

Sporadic porphyria cutaneous tarda also called type 1 porphyria cutaneous tarda generally begins in mid-adult life after exposure to certain chemicals that increase the production of porphyrins (precursors of heme) in the liver. These include:

- alcohol (in 50% patients)

- estrogen eg oral contraceptive, hormone replacement (in 50% of affected women) or liver disease

- polychlorinated aromatic hydrocarbons (eg, dioxins, when porphyria cutaneous tarda is associated with chloracne).

- iron overload, due to excessive intake (orally or by blood transfusion), viral infections (hepatitis, especially hepatitis C, in 15%) or chronic blood disorders such as thalassemia (acquired hemochromatosis), or hereditary hemochromatosis (in 20%)

Type 1 porphyria cutaneous tarda usually first develops over the age of 40 and seems to be more common in men than in women. The most frequent presentation is with blisters, skin fragility, and delayed healing of wounds on the maximally photo-exposed sites of dorsal hands. Upon healing, the subepidermal blisters of porphyria cutaneous tarda typically result in milia; classically, these are seen on the maximally photo-exposed sites of the dorsal hands. In most porphyria cutaneous tarda patients, this means most frequent localisation over dorsal thenar eminences, proximal index and middle fingers, and thumbs. Different distributions can be seen dependent upon the patient’s occupation; for example, a taxi driver with more involvement of distal dorsal fingers and with finger nail changes, including onycholysis. Hypertrichosis also frequently appears; it often first manifests on the temples but can appear in areas that are not photo-exposed. Another frequent feature is pigmentation, particularly of areas that are photo-exposed, and is sometimes the only presenting sign. Solar urticaria is rarely seen on presentation 7, although urticarial responses can be found on monochromator phototesting 8.

Type 2 porphyria cutaneous tarda also called familial porphyria cutanea tarda, is familial and associated with abnormal genetic variants of uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase. The familial form accounts for 10-20% of all cases of porphyria cutanea tarda. Autosomal dominant hepatoerythropoietic porphyria (a severe rare homozygous form) also exists, but environmental factors are also important in the expression of the disease. Biochemically, minor rises in liver toxicity and ferritin concentrations are common. Liver biopsy usually shows fatty infiltration and inflammatory changes, with cirrhosis being present in a third of cases 9. Trigger factors are less often involved and onset of porphyria cutaneous tarda is often younger than in type 1 porphyria cutaneous tarda.

Cutaneous porphyria symptoms

Individuals with porphyria cutaneous tarda present with increasingly fragile skin on the back of the hands and the forearms. Features include:

- Sores (erosions) following relatively minor injuries

- Fluid filled blisters (vesicles and bullae)

- Tiny cysts (milia) arising as the blisters heal

- Increased sensitivity to the sun

Although these features may also occur on the face and neck as well, it is more common to notice mottled brown patches around the eyes and increased facial hair (hypertrichosis). Occasionally the skin becomes hardened (scleroderma) on the neck, face or chest. There may be small areas of permanent baldness (alopecia) or ulcers. Scleroderma-like changes are infrequent in porphyria cutaneous tarda but have been thoroughly reported 10. Many porphyria cutaneous tarda sufferers are not initially aware of the involvement of sunlight. This is because (1) it is visible (not ultraviolet) wavelength radiation that leads to the changes in the skin, so seasonal variation is not always apparent, and (2) it is mainly chronic, and not discrete episodes of, sunlight exposure that result in symptoms.

Characteristically, the urine is darker than usual, with a reddish or tea-colored hue.

The clinical appearance of variegate porphyria is similar but the biochemical abnormality is different.

Cutaneous porphyria diagnosis

Diagnosis of the porphyrias is as with other conditions starts with history and examination. If a cutaneous porphyria like porphyria cutaneous tarda is in the differential, a porphyrin plasma scan (plasma spectrofluorimetry) and quantitative urine porphyrins are appropriate initial tests 11. If these are positive, then fluorescent high-performance liquid chromatography on urine and stool porphyrins are appropriate in order to differentiate among porphyria cutaneous tarda, variegate porphyria, and hereditary coproporphyria. If acquired porphyria cutaneous tarda is strongly suspected, it is appropriate to start investigating for underlying causes, including iron accumulation, chronic hepatitis B or C, or HIV, even while still investigating to determine whether the patient does have porphyria cutaneous tarda. If erythropoietic protoporphyria is considered, then it is appropriate to request a porphyrin plasma scan and quantitative erythrocyte protoporphyrin.

- Skin biopsy : characteristic changes are seen which differentiates porphyria cutaneous tarda from other blistering diseases.

- Examination of the urine with a Wood’s lamp: may reveal coral pink fluorescence due to excessive porphyrins.

- 24 hour urine porphyrin profile: total porphryins are usually elevated 5- to 20-fold above the upper reference limit. Most of the excreted porphyrins are uroporphyrin and a 7-carboxyl porphyrin.

Other important tests include:

- Complete blood count to assess hemoglobin levels.

- Measurement of iron stores, which may be increased in over 30% of patients.

- Liver enzymes because the liver sometimes does not function normally.

- Fasting blood sugar because of the increased incidence of diabetes.

- Antinuclear antibodies because of the increased incidence of lupus erythematosus (SLE).

- Viral hepatitis studies

- A liver ultrasound is often done (particularly to look for hepatocellular carcinoma) but liver biopsy is rarely indicated. In areas where there is a high prevalence of HIV, patients should always undergo HIV serologic testing. In areas where there is a low prevalence, the occurrence of HIV testing is expected to be low, but investigation must still take place if there are other pointers to this diagnosis (such as mouth ulcers, chronic diarrhoea, weight loss, or behavioural risk factors) or, regardless of the presence or absence of behavioural/lifestyle risk factors, if the porphyria cutaneous tarda presentation is unusual (for example, in a young woman who drinks little alcohol) and initial investigations have been unrewarding.

If a blood ferritin shows iron stores are increased, further investigations may include transferrin saturation and genotyping for hereditary hemochromatosis.

Cutaneous porphyria treatment

Management involves eliminating the causes of underlying liver disease and iron overload when possible. Patients should be advised to avoid alcohol (irrespective of whether or not it is thought to be the cause of the primary liver insult), medications containing iron must be stopped, and estrogens should be stopped or changed to low systemic dose transdermal preparations. When possible, viral hepatitis should be treated, and several porphyria cutaneous tarda patients over the past two decades have been cured by some of the newer anti–hepatitis C drugs. The likelihood of hepatitis C treatment being effective is possibly increased if iron overload is addressed first 12. Iron overload is usually treated by venesection. Iron chelation therapy (with desferrioxamine or one of the newer oral iron chelators) is an alternative approach that can be useful when iron overload is associated with anemia (such as in a hemodialysis patient with porphyria cutaneous tarda) 13.

Another approach, which can be combined with venesection, is to treat with low-dose chloroquine or hydroxychloroquine. These drugs are thought to work by increasing porphyrin excretion. Chloroquine rather than hydroxychloroquine is usually used, as there is more experience in using this in porphyria cutaneous tarda and the doses used (such as 250 mg chloroquine phosphate weekly) are low enough that ocular toxicity is not an important concern 14. Owing to the risks of severe hepatotoxicity, higher doses should not be used. While patients await the effects of these treatments, adopting sunlight avoidance measures is important. Visible-light exposure can be lowered by behavioural avoidance, wearing suitable clothing (for example, dark-coloured driving gloves), and applying a large-particle-size titanium dioxide sunblock. Also, protecting the hands from trauma during manual work and leisure activities (such as gardening) by wearing gloves is beneficial. For male patients, the use of an emulsifying ointment as an alternative to shaving foam, applied for 10 minutes before shaving, can help reduce facial shaving trauma.

- Avoid alcohol, estrogen, and iron.

- If using pesticides, be very careful to avoid contact with polychlorinated aromatic hydrocarbons (eg. 2,4,5T).

- Apply an opaque sun-block and cover up when outside; the responsible light is the “Soret” band at 400 nm which is unfortunately not blocked by most sunscreens.

- Use tanning cream containing dihydroxyacetone: this can block the responsible light to some extent.

- Phlebotomy (removal of blood) — up to 500 ml blood is removed every one to two weeks until the haemoglobin and iron levels drop to low normal levels. It may take 3 to 6 months to improve. Venesection may need to be repeated after a year or more.

- Antimalarial tablets, ie, low-dose chloroquine or hydroxychloroquine may be recommended, but must be used cautiously. This medication makes the porphyrins more soluble so more are excreted in the urine.

- Autologous red cell transfusion (this is a blood transfusion using the patient’s own red cells that have been washed to remove plasma thereby reducing the circulating porphyrins).

- Porphyria cutaneous tarda in patients with hepatitis C may resolve with treatment with direct acting antiviral drugs.

- Edel Y, Mamet R. Porphyria: What Is It and Who Should Be Evaluated?. Rambam Maimonides Med J. 2018;9(2):e0013. Published 2018 Apr 19. doi:10.5041/RMMJ.10333 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5916231[↩][↩]

- Dawe R. An overview of the cutaneous porphyrias. F1000Res. 2017;6:1906. Published 2017 Oct 30. doi:10.12688/f1000research.10101.1 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5664971[↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Karim Z, Lyoumi S, Nicolas G, Deybach JC, Gouya L, Puy H. Porphyrias: a 2015 update. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2015;39:412–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinre.2015.05.009[↩]

- Bissell DM, Lai JC, Meister RK, Blanc PD. Role of delta-aminolevulinic acid in the symptoms of acute porphyria. Am J Med. 2015;128:313–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2014.10.026[↩]

- Schulenburg-Brand D, Katugampola R, Anstey AV, Badminton MN. The cutaneous porphyrias. Dermatol Clin. 2014;32:369–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.det.2014.03.001[↩]

- Porphyria cutanea tarda. Elder GH. Semin Liver Dis. 1998; 18(1):67-75.[↩]

- Dawe RS, Clark C, Ferguson J: Porphyria cutanea tarda presenting as solar urticaria. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141(3):590–1. 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1999.03076.x[↩]

- Ichihashi M, Hasei K, Horikawa T: A case of porphyria cutanea tarda with experimental light urticaria. Br J Dermatol. 1985;113(6):745–50. 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1985.tb02411.x[↩]

- Elder GH. Porphyria cutanea tarda: a multifactorial disease. In: Champion RH, Pye RJ, editors. Recent advances in dermatology. No 8. Edinbrugh: Churchill Livingstone; 1990. pp. 55–70.[↩]

- Karamfilov T, Buslau M, Dürr C, et al. : [Pansclerotic porphyria cutanea tarda after chronic exposure to organic solvents]. Hautarzt. 2003;54(5):448–52. 10.1007/s00105-002-0448-3[↩]

- Woolf J, Marsden JT, Degg T, et al. : Best practice guidelines on first-line laboratory testing for porphyria. Ann Clin Biochem. 2017;54(2):188–98. 10.1177/0004563216667965[↩]

- Fontana RJ, Israel J, LeClair P, et al. : Iron reduction before and during interferon therapy of chronic hepatitis C: results of a multicenter, randomized, controlled trial. Hepatology. 2000;31(3):730–6. 10.1002/hep.510310325[↩]

- Vasconcelos P, Luz-Rodrigues H, Santos C, et al. : Desferrioxamine treatment of porphyria cutanea tarda in a patient with HIV and chronic renal failure. Dermatol Ther. 2014;27(1):16–8. 10.1111/dth.12024[↩]

- Elder GH: The cutaneous porphyrias. Semin Dermatol. 1990;9(1):63–9.[↩]