Dermatopolymyositis

Dermatopolymyositis is a family of autoimmune disorders that is characterized by inflammatory and degenerative changes in the muscles (polymyositis) or in the skin and muscles (dermatomyositis). As such, dermatopolymyositis includes both a distinctive skin rash and progressive muscular weakness. Dermatopolymyositis is a rare disease.

Classification of autoimmune myositis:

- Dermatomyositis: inflammation of voluntary muscles (myositis) in association with a rash. Dermatomyositis is an uncommon idiopathic inflammatory myopathy with skin manifestations that vary in severity. Dermatomyositis may affect people of any race, age or sex, although it is twice as common in women than in men. Incidence is estimated at 1 per 100 000 population, with peaks at ages 5–15 years in children and ages 45–60 years in adults 1. The onset of the disease is most common in those aged 50–70 years. Dermatomyositis rashes are commonly photosensitive; therefore, other diagnostic considerations include subacute cutaneous lupus, contact dermatitis, drug rash and phototoxic reaction.

- Polymyositis: myositis without rash

- Juvenile dermatomyositis or juvenile polymyositis: myositis and skin rash occurring in children < 18 years. Juvenile dermatomyositis is an inflammatory disease of the muscle (myositis), skin, and blood vessels. Patients with juvenile dermatomyositis have varying symptoms ranging from mild muscle weakness like difficulty getting out of a chair or difficulty turning over in bed to severe symptoms including profound weakness or difficulty swallowing. Patients can also develop rash or skin changes ranging from mild redness to more severe ulcer formation.

- Amyopathic dermatomyositis: typical skin rash develops without evidence of muscle involvement. Also called dermatomyositis sine myositis.

- Antisynthetase syndrome: myositis, arthritis, interstitial lung disease, mechanic’s hands and Raynaud phenomenon

Dermatomyositis is a multisystem autoimmune disease manifesting as an idiopathic inflammatory myopathy, characterized predominantly by cutaneous and muscular abnormalities 2. Patients with dermatomyositis display characteristic skin changes in addition to muscle weakness. Many consider dermatomyositis a paraneoplastic syndrome, as up to 32% of patients with dermatomyositis will develop cancer 2.

Dermatomyositis is an autoimmune disease with multiple dermatologic changes, chronic muscle inflammation, proximal muscle weakness and extramuscular manifestations, including interstitial lung disease 3. Immunologically, there are several autoantibody specificities, each associated with particular clinical features. Incidence of dermatomyositis is 1.0 per 100 000 person-years in British Columbia 4.

Dermatomyositis can be distinguished from polymyositis by the characteristic skin findings of dermatomyositis (see Symptoms and Signs). Muscle histopathology also differs. Dermatomyositis and polymyositis can manifest as pure muscle diseases or as part of antisynthetase syndrome when associated with arthritis (usually nonerosive), fever, interstitial lung disease, hyperkeratosis of the radial aspect of the digits (mechanic’s hands), and Raynaud syndrome.

Despite the gains in knowledge of dermatomyositis, the overall mortality is still up to sevenfold higher than that of the general population 5. Additionally, those with dermatomyositis have a substantially increased morbidity when compared with the population at large 6. The increased risk of malignant disease 5, cardiovascular events 7 and interstitial lung disease 8 in dermatomyositis is well-established. However, the risk of other comorbidities in dermatomyositis has been overlooked. Although an association with Sjögren syndrome has been shown in other autoimmune diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis 9, systemic lupus erythematosus 10 and systemic sclerosis 11, data on Sjögren syndrome in patients with dermatomyositis are sparse and mostly limited to case reports 12.

Necrotizing immune-mediated myopathies include signal recognition particle antibody–related myositis and statin-induced myositis, usually have an aggressive presentation, have very elevated creatine kinase (CK) levels, and do not involve extramuscular organs.

Inclusion body myositis is a separate disorder that has clinical manifestations similar to chronic idiopathic polymyositis; however, it develops at an older age, frequently involves distal muscles (eg, hand and foot muscles) often with muscle wasting, has a slower progression, and does not respond to therapy (immunosuppressive therapy).

Autoimmune myositis can also overlap with other autoimmune rheumatic disorders—eg, systemic lupus erythematosus, systemic sclerosis, mixed connective tissue disease. These patients have symptoms and signs of the overlap disorders in addition to myositis (manifest as either dermatomyositis or polymyositis).

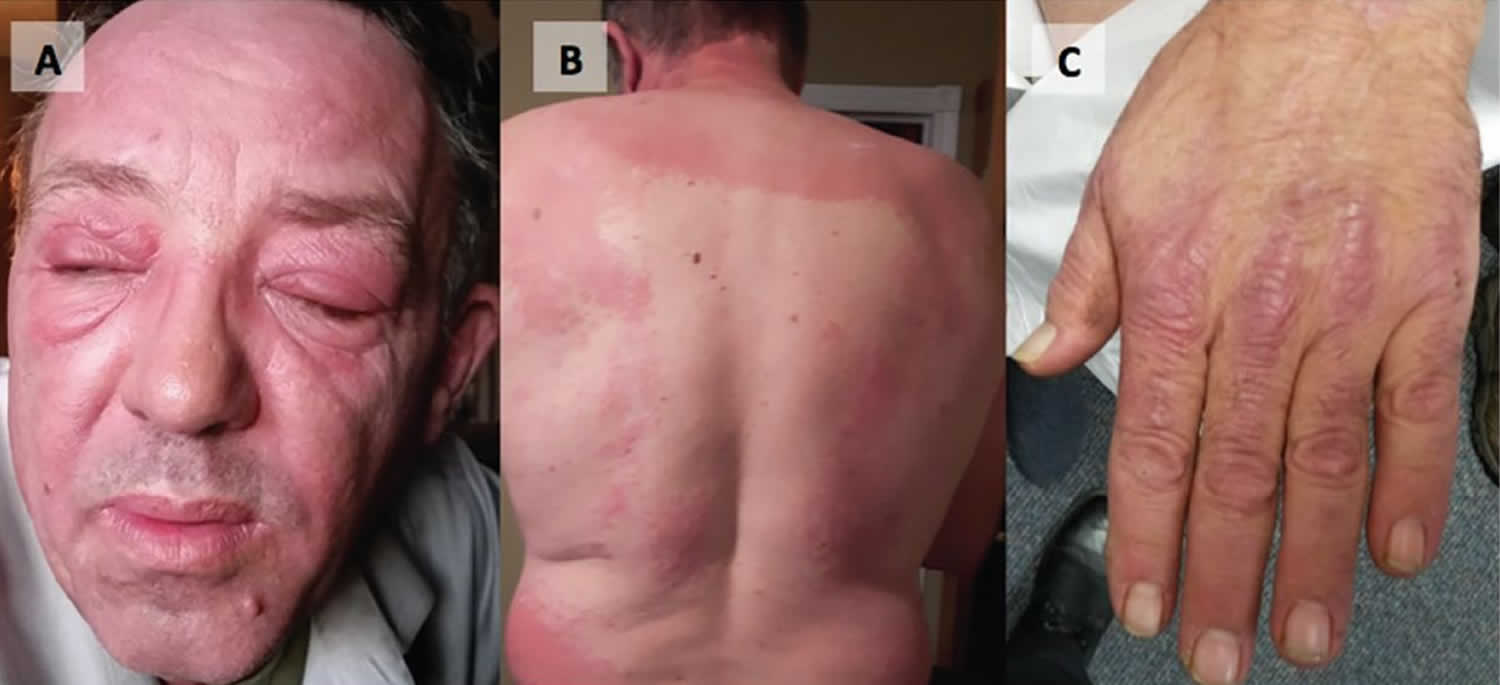

Figure 1. Juvenile dermatopolymyositis

Dermatopolymyositis causes

Dermatomyositis is considered one of the connective tissue diseases, like systemic sclerosis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Dermatomyositis is thought to be caused by microangiopathy affecting skin and muscle.

Factors that may play a part in its development are listed below.

- Genetic predisposition

- Underlying cancer (more likely in older people)

- Autoimmune defect (an immune reaction against self)

- Infectious or toxic agents acting as triggers

- Certain drugs, which include hydroxyurea, penicillamine, statins, quinidine, and phenylbutazone

The cause of autoimmune myositis seems to be an autoimmune reaction to muscle tissue in genetically susceptible people. Familial clustering occurs, and human leukocyte antigen (HLA) subtypes are associated with myositis. For example, the alleles of the 8.1 ancestral haplotype (HLA-DRB1*03-DQA1*05-DQB1*02) increase risk of polymyositis, dermatomyositis, and interstitial lung disease. Possible inciting events include viral myositis and underlying cancer. The association of cancer with dermatomyositis (less so with polymyositis) suggests that a tumor may incite myositis as the result of an autoimmune reaction against a common antigen in muscle and tumor.

Dermatopolymyositis symptoms

Dermatomyositis is characterised by cutaneous features and myositis.

Skin features

In many patients, the first sign of dermatomyositis is the presence of a symptomless, itchy or burning rash. The rash often, but not always, develops before the muscle weakness.

- Reddish or bluish-purple patches mostly affect sun-exposed areas.

- A violaceous rash may also affect cheeks, nose, shoulders, upper chest and elbows.

- Purple eyelids, which are described as heliotrope, as they resemble the heliotrope flower, Heliotropium peruvianum, which has small purple petals.

- A scaly scalp and thinned out hair may occur.

- Less commonly, there is poikiloderma, in which the skin is atrophic (pale, thin skin), red (dilated blood vessels) and brown (post-inflammatory pigmentation).

- Purple papules or plaques are found on bony prominences, especially the knuckles (Gottron papules).

- Ragged cuticles and prominent blood vessels on nail folds are best seen by capillaroscopy or dermoscopy.

Skin changes, which occur in dermatomyositis, tend to be dusky and erythematous. Photosensitivity and skin ulceration are visible. Periorbital edema with a purplish appearance (heliotrope rash) is relatively specific for dermatomyositis. Elsewhere, the rash may be slightly elevated and smooth or scaly; it may appear on the forehead, V of the neck and shoulders, chest and back, forearms and lower legs, elbows and knees, medial malleoli, and radiodorsal aspects of the proximal interphalangeal and metacarpophalangeal joints (Gottron papules—also a relatively specific finding). The base and sides of the fingernails may be hyperemic or thickened. Desquamating dermatitis with splitting of the skin may evolve over the radial aspects of the fingers. Subcutaneous and muscle calcification may occur, particularly in children. The primary skin lesions frequently fade completely but may be followed by secondary changes (eg, brownish pigmentation, atrophy, persistent neovascularization, scarring). Rash on the scalp may appear psoriaform and be intensely pruritic. Characteristic skin changes can occur in the absence of muscle disease, in which case the disease is called amyopathic dermatomyositis.

Myositis

Myositis almost always causes loss of muscle strength. Muscle weakness may arise at the same time as the dermatomyositis rash, or it may occur weeks, months or years later. Proximal muscles are affected, that is, those closest to the trunk (upper arms, thighs). Weakness in the large muscles around the neck, shoulders and hips. The first indication of myositis is when the following everyday movements become difficult:

- Climbing stairs or walking

- Rising from a sitting or crouching position

- Lifting objects

- Raising arms above the shoulders, such as when combing hair

- Difficulty swallowing (dysphagia)

- Choking while eating or aspiration (intake) of food into the lungs

- Little, if any, pain in the muscles

- Shortness of breath and cough

Occasionally the affected muscles ache and become tender to touch.

Onset of autoimmune myositis may be acute (particularly in children) or insidious (particularly in adults). Polyarthralgias, Raynaud syndrome, dysphagia, pulmonary symptoms (eg, cough, dyspnea), and constitutional complaints (notably fever, fatigue, and weight loss) may also occur. Severe disease is characterized by dysphagia, dysphonia, and/or diaphragmatic weakness.

Muscle weakness may progress over weeks to months. However, it takes destruction of 50% of muscle fibers to cause symptomatic weakness (ie, muscle weakness indicates advanced myositis). Patients may have difficulty raising their arms above their shoulders, climbing steps, or rising from a sitting position. Sometimes muscle tenderness and atrophy develop. Patients may require the use of a wheelchair or become bedridden because of weakness of pelvic and shoulder girdle muscles. The flexors of the neck may be severely affected, causing an inability to raise the head from the pillow. Involvement of pharyngeal and upper esophageal muscles may impair swallowing and predispose to aspiration. Muscles of the hands, feet, and face are not involved except in inclusion body myositis, in which distal involvement, especially of the hands, is characteristic. Limb contractures may eventually develop.

Joint manifestations include polyarthralgia or polyarthritis, often with swelling, effusions, and other characteristics of nondeforming arthritis. They occur more often in a subset with Jo-1 or other antisynthetase antibodies.

Visceral involvement (except that of the pharynx and upper esophagus) is less common in autoimmune myositis than in some other rheumatic disorders (eg, systemic lupus erythematosus, systemic sclerosis). Occasionally, and especially in patients with antisynthetase antibodies, interstitial lung disease (manifested by dyspnea and cough) is the most prominent manifestation. Cardiac involvement, especially conduction disturbances and ventricular dysfunction, can occur. Gastrointestinal symptoms, more common among children, are due to an associated vasculitis and may include abdominal pain, hematemesis, melena, and ischemic bowel perforation.

Dermatopolymyositis diagnosis

A doctor suspects dermatomyositis when patients complain of trouble doing tasks that require muscle strength, or when they get certain rashes or breathing problems. Most people with dermatomyositis have little or no pain in their muscles. A doctor will do a muscle strength exam to find if true muscle weakness is present.

The following tests usually confirm the diagnosis of dermatomyositis:

- A blood test to detect raised circulating muscle enzymes: creatine kinase (CK) and sometimes aldolase, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and lactic dehydrogenase (LDH)

- A blood test to detect autoantibodies: non-specific antinuclear antibody (ANA) is found in most patients, specific Anti-Mi-2 is found in one quarter and Anti-Jo-1 in a few, usually those who have lung disease, and are diagnostic of antisynthetase syndrome.

- Electromyography (EMG) testing – to gauge electrical activity in muscle

- Skin biopsy of the rash: the microscopic appearance of an interface dermatitis is similar to systemic (acute) lupus erythematosus

- A biopsy of a weak muscle (a small piece of muscle tissue is removed for testing)

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan of muscles – to try to show abnormal muscle

In adults, dermatomyositis and, to a much lesser extent, polymyositis at times may be linked to cancer. Therefore, all adults with these diseases should have full body examination and tests to rule out cancer.

As proposed by Bohan and Peter in 1975 13, a definite diagnosis requires 4 or more of the following criteria:

- symmetric proximal weakness,

- elevated levels of serum muscle enzymes,

- characteristic electromyography changes,

- characteristic muscle biopsy changes, and

- typical skin lesions that may include scalp dermatosis, heliotrope rash, photosensitive poikiloderma, V sign (rash on anterior neck), shawl sign, Gottron papules or Holster sign (rash over lateral hip).

About 10% of patients will have amyopathic dermatomyositis with no apparent muscle involvement, frequently associated with anti-MDA5 antibody. Other manifestations may include arrhythmias, interstitial lung disease and inflammatory arthritis 14.

Dermatopolymyositis treatment

The primary aim of treatment is to control the skin disease and muscle disease. Corticosteroids are the drugs of choice initially. An oral corticosteroid such as prednisone in moderate to high dose is the mainstay of medical therapy and is given to slow down the rate of disease progression.

For acute disease, adults receive oral prednisone 1 mg/kg (usually about 40 to 60 mg) once a day. For severe disease with dysphagia or respiratory muscle weakness, treatment usually starts with pulse corticosteroid therapy (eg, methylprednisolone 0.5 to 1 g IV once a day for 3 to 5 days).

Serial measurements of creatinine kinase (CK) provide the best early guide of therapeutic effectiveness. However, in patients with widespread muscle atrophy, levels are occasionally normal despite chronic, active myositis. MRI findings of muscle edema or high CK levels generally differentiate a relapse of myositis from corticosteroid-induced myopathy. Aldolase is an alternative, being less specific for muscle injury than CK, but can be positive in patients with myositis and normal CK levels. Enzyme levels fall toward or reach normal in most patients in 6 to 12 weeks, followed by improved muscle strength. Once enzyme levels have returned to normal, prednisone can be gradually reduced. CK normalization usually precedes return of muscle strength. If muscle enzyme levels rise, the dose is increased.

The overall goal is to minimize corticosteroid exposure, which is why a second drug (typically methotrexate, tacrolimus, or azathioprine as first-line noncorticosteroid drugs) is started at the same time as corticosteroids or shortly after so that prednisone can be tapered to a maximum dose of 5 mg a day, ideally within about 6 months. IV immune globulin is a good option for patients who do not respond rapidly to therapy, develop infectious complications with high-dose corticosteroids and other immunosuppressants, or who are undergoing chemotherapy. Some experts may use a combination of all 3 therapies in severe cases or when corticosteroid toxicity is present. Children require initial doses of prednisone of 30 to 60 mg/m2 once a day.

Occasionally, patients treated chronically with high-dose corticosteroids become increasingly weak after the initial response because of a superimposed, painless corticosteroid myopathy. In these patients, CK remains normal even though the patients are weaker.

Myositis associated with cancer is more refractory to corticosteroids. Cancer-associated myositis may remit if the tumor is removed.

People with an autoimmune disorder are at higher risk of atherosclerosis and should be closely monitored. Patients on long-term corticosteroid therapy should receive osteoporosis prophylaxis. Prophylaxis for opportunistic infections, such as Pneumocystis jirovecii (see prevention of Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia), should be added if combination immunosuppressive therapy is used.

Hydroxychloroquine may reduce the photosensitive rash. Note that adverse cutaneous reactions to hydroxychloroquine are reported to affect more than 30% of patients with dermatomyositis, compared to a lower risk of rash in patients with cutaneous lupus erythematosus 15.

Immunosuppressive or cytotoxic drugs may also be used including methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil, azathioprine, cyclophosphamide, ciclosporin, high dose intravenous immunoglobulin and experimentally, biologics such as rituximab.

- Diltiazem, a calcium channel blocker usually prescribed for high blood pressure, may reduce calcinosis.

- Colchicine has also been reported to reduce calcinosis.

- Patients should strictly avoid excessive sun exposure and use sun protection, including fully covering clothing and broad-spectrum sunscreens to minimise the harmful effects of the sun on already damaged and photosensitive skin.

- Bedrest may be required for severely inflamed muscles

- Physical therapy and activity are recommended to keep the muscles and joints moving.

- Those with difficulty swallowing should avoid eating food before bedtime and raise the bed head for sleeping.

Dermatopolymyositis prognosis

Most patients will require treatment throughout their lifetime, but dermatomyositis completely resolves in about one-in-five patients. Long remissions (even apparent recovery) occur in up to 50% of treated patients within 5 years, more often in children. Relapse, however, may still occur at any time. Overall 5-year survival rate is 75% and is higher in children. Death in adults is preceded by severe and progressive muscle weakness, dysphagia, undernutrition, aspiration pneumonia, or respiratory failure with superimposed pulmonary infection. Death in children with dermatomyositis may be a result of bowel vasculitis. Dermatomyositis and polymyositis have been linked to an increased cancer risk.

Patients who have a disease affecting their heart or lungs, or who also have underlying cancer, do less well and may ultimately die from their disease.

- Bendewald MJ, Wetter DA, Li X, et al. Incidence of dermatomyositis and clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis: a population-based study in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Arch Dermatol 2010;146:26–30.[↩]

- Laidler NK. Dermatomyositis as a paraneoplastic phenomenon in oesophageal cancer. BMJ Case Reports CP 2018;11:e227387.[↩][↩]

- Sex differential association of dermatomyositis with Sjögren syndrome. Chia-Chun Tseng, Shun-Jen Chang, Wen-Chan Tsai, Tsan-Teng Ou, Cheng-Chin Wu, Wan-Yu Sung, Ming-Chia Hsieh, Jeng-Hsien Yen. CMAJ Feb 2017, 189 (5) E187-E193; DOI: 10.1503/cmaj.160783[↩]

- Avina-Zubieta JA, Sayre EC, Bernatsky S, et al. Adult prevalence of systemic autoimmune rheumatic diseases (SARDs) in British Columbia, Canada [abstract]. Arthritis Rheum 2011; 63(Suppl 10):1846.[↩]

- Kuo CF, See LC, Yu KH, et al. Incidence, cancer risk and mortality of dermatomyositis and polymyositis in Taiwan: a nationwide population study. Br J Dermatol 2011;165:1273–9.[↩][↩]

- Marie I. Morbidity and mortality in adult polymyositis and dermatomyositis. Curr Rheumatol Rep 2012;14:275–85.[↩]

- Rai SK, Choi HK, Sayre EC, et al. Risk of myocardial infarction and ischaemic stroke in adults with polymyositis and dermatomyositis: a general population-based study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2016;55:461–9.[↩]

- Chen YJ, Wu CY, Shen JL. Predicting factors of interstitial lung disease in dermatomyositis and polymyositis. Acta Derm Venereol 2007;87:33–8.[↩]

- Bettero RG, Cebrian RF, Skare TL. Prevalence of ocular manifestation in 198 patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a retrospective study. Arq Bras Oftalmol 2008;71:365–9.[↩]

- Chambers SA, Charman SC, Rahman A, et al. Development of additional autoimmune diseases in a multiethnic cohort of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus with reference to damage and mortality. Ann Rheum Dis 2007; 66:1173–7.[↩]

- Muangchan C, Baron M, Pope J. Canadian Scleroderma Research Group. The 15% rule in scleroderma: the frequency of severe organ complications in systemic sclerosis. A systematic review. J Rheumatol 2013;40:1545–56.[↩]

- Ortigosa LC, Reis VM. Dermatomyositis: analysis of 109 patients surveyed at the Hospital das Clínicas (HCFMUSP), São Paulo, Brazil. An Bras Dermatol 2014;89:719–27.[↩]

- Bohan A, Peter JB. Polymyositis and dermatomyositis (first of two parts). N Engl J Med. 1975;292(7):344-347. doi:10.1056/NEJM197502132920706[↩]

- Bailey EE, Fiorentino DF. Amyopathic dermatomyositis: definitions, diagnosis, and management. Curr Rheumatol Rep 2014;16:465.[↩]

- Pelle MT, Callen JP. Adverse cutaneous reactions to hydroxychloroquine are more common in patients with dermatomyositis than in patients with cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138(9):1231-1233. doi:10.1001/archderm.138.9.1231[↩]