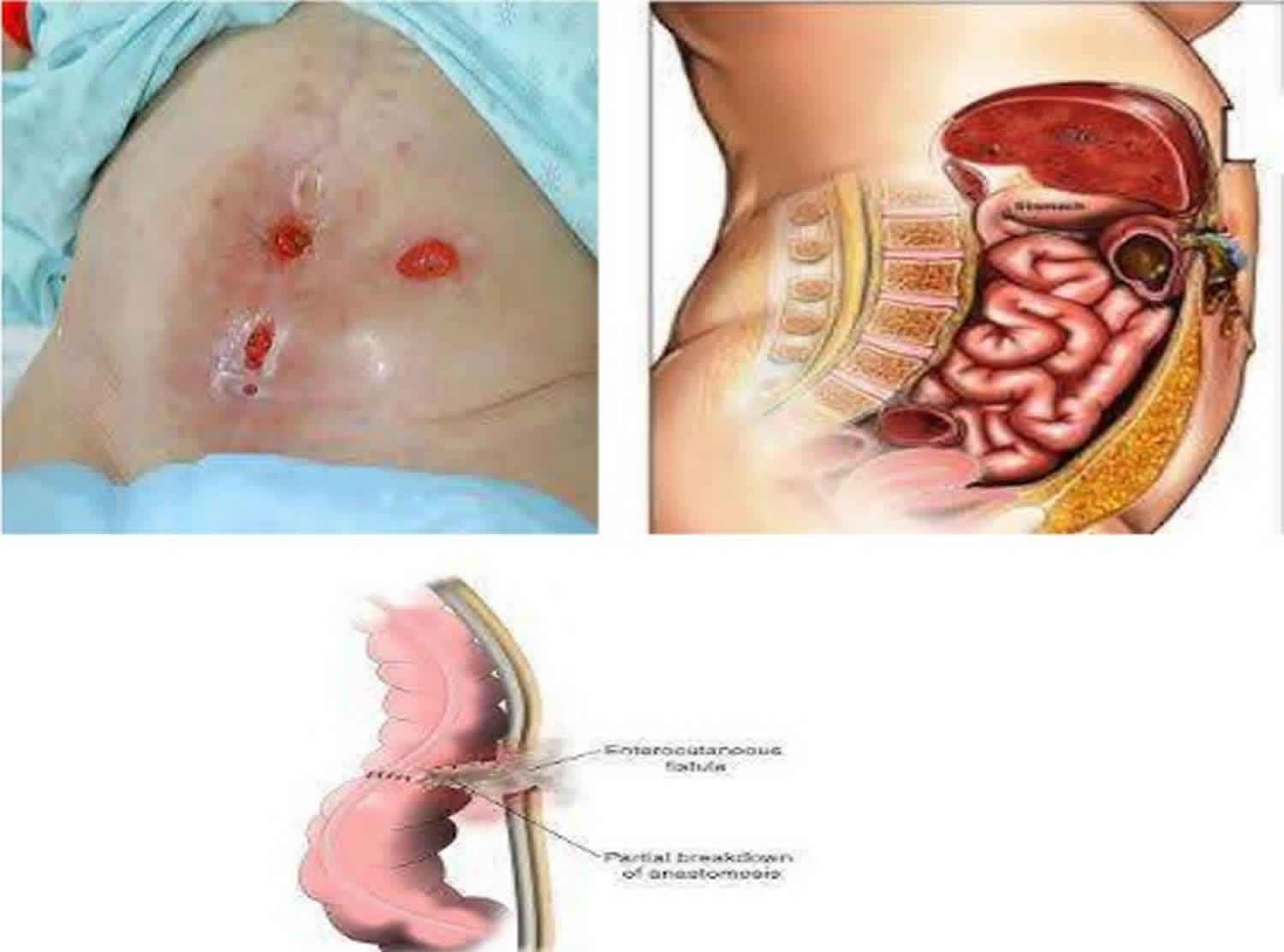

Enterocutaneous fistula

Enterocutaneous fistula is an abnormal connection or fistula that starts from the small intestine and ends or opens to the skin. When categorized physiologically, enterocutaneous fistula is differentiated based on fluid output. Low-output fistulas drain less than 200 ml of fluid per day, high-output fistulas drain greater than 500 ml of fluid per day, and medium-output fistulas fall between the two.

The pathophysiology of an enterocutaneous fistula is simple since it is nothing more than an abnormal connection between the small intestine and skin. Anything that causes a potential communication between the the small intestine and the epidermis can lead to the development of an enterocutaneous fistula. A constant stream of fluid traveling through this connection will keep the tract patent, and it will provide time for epithelial tissue to migrate into and cover the inner surface of the tract. Epithelialization of the tract will further stabilize the patency of the fistula. These factors contribute to the reasons why short, wide, high output fistulas are more prone to stabilize than long, narrow, low-output fistulas 1.

The most common cause of an enterocutaneous fistula is iatrogenic and occurs in the postoperative period. A history of trauma, inflammatory bowel disease, and oncologic surgery places patients at a high risk of developing enterocutaneous fistula.

Enterocutaneous fistula mortality rates vary from 6% to 33% 2. Incidence is dependent on the cause. Infected pancreatic necrosis has an extremely high incidence of 50%. Trauma patients have a 2% to 25% incidence, and abdominal sepsis has a 20% to 25% incidence 3.

Enterocutaneous fistulas are best managed by a multidisciplinary team that includes a stoma or wound care nurse, dietitian, and therapist. The key is to replace any fluids and electrolytes promptly because these patients can decompensate quickly. The source of sepsis has to be identified. The conventional therapy for an enterocutaneous fistula in the initial phase is always conservative 4. Immediate surgical therapy on presentation is contraindicated, because the majority of enterocutaneous fistulas spontaneously close as a result of conservative therapy. Surgical intervention in the presence of sepsis and poor general condition would be hazardous for the patient. However, patients who have an enterocutaneous fistula with adverse factors, such as a lateral duodenal fistula, an ileal fistula, a high-output fistula, or a fistula associated with a diseased bowel, may require early surgical intervention.

The outcomes depend on the cause of the enterocutaneous fistula; malignant cases usually have a poor outcome but those in patients with Crohn’s disease can take months or years to close.

Enterocutaneous fistula causes

It is estimated that 80% of enterocutaneous fistulas are of iatrogenic origin secondary to surgery 2. Surgical complications, such as enterotomies or intestinal anastomotic dehiscence, are known to be at high risk for the development of an enterocutaneous fistula. Trauma, malignancy, and inflammatory bowel disease increase risk of fistula development postoperatively. The 20% of fistulas not associated with surgery are caused by systemic diseases such as Crohn’s disease, radiation enteritis, malignancies, trauma, or ischemia 5.

The following scenario is an example of the events leading up to the development of an enterocutaneous fistula. A patient with a postoperative fever, leukocytosis, ileus, and abdominal tenderness is found to have a wound infection. The next step in treating this patient is to drain the abscess. However, one or two days after draining the abscess, enteric contents are observed in the wound. Finding enteric contents that are continually leaking into the wound establishes a diagnosis of an enterocutaneous fistula.

A helpful, commonly used acronym for remembering the factors that make fistula formation favorable and unlikely to spontaneously regress is “FRIEND.” The acronym is remembered easily with the mnemonic “the friends of the fistula” 6:

- F – Foreign body

- R – Radiation

- I – Inflammation or infection

- E – Epithelialization of the fistula tract

- N – Neoplasm

- D – Distal obstruction

Enterocutaneous fistula symptoms

Features suggestive of an enterocutaneous fistula (enterocutaneous fistula) include postoperative abdominal pain, tenderness, distention, enteric contents from the drain site, and the main abdominal wound. Tachycardia and pyrexia may also be present, as may signs of localized or diffuse peritonitis, including guarding, rigidity, and rebound tenderness.

The type of enterocutaneous fistula, as based on the output of the enteric contents, also determines the patient’s health status and how the patient may respond to therapy. enterocutaneous fistulas are usually classified into three categories, as follows 7:

- Low-output fistula (< 200 mL/day),

- Moderate-output fistula (200-500 mL/day)

- High-output fistula (>500 mL/day)

Skin excoriation is one of the complications that can lead to significant morbidity in patients with enterocutaneous fistula. When the enteric contents are more fluid than solid, this becomes a difficult problem; the skin excoriation makes it difficult to put a collecting bag or dressings over the fistula, and more leakage leads to an increase in the excoriation.

Enterocutaneous fistula complications

Patients with enterocutaneous fistula present with associated complications, such as sepsis, fluid and electrolyte abnormalities, and malnutrition.

The degree of sepsis depends on the state of the enterocutaneous fistula. If the fistula forms a direct tract through which the bowel contents are draining onto the skin, then the sepsis may be minimal, whereas if the fistula forms an indirect tract through which the bowel contents are draining into an abscess cavity and then onto the skin, the degree of sepsis may be higher. In the presence of extensive peritoneal contamination or generalized peritonitis with enterocutaneous fistula, the patient can be toxic due to severe sepsis.

Leakage of protein-rich enteric contents, intra-abdominal sepsis, or electrolyte imbalance–related paralytic ileus, as well as a general feeling of ill health, leads to reduced nutritional intake by these patients, resulting in malnutrition. Nearly 70% of patients with enterocutaneous fistulas may have malnutrition, and it is a significant prognostic factor for spontaneous fistula closure 8.

Sepsis, malnutrition, and electrolyte imbalance are the predominant factors that lead to death in patients with enterocutaneous fistula 9. Rarely, intestinal failure can occur as one of the complications of enterocutaneous fistula, which results in significant morbidity and mortality 10.

A high-output fistula increases the possibility of fluid and electrolyte imbalance and malnutrition.

Enterocutaneous fistula diagnosis

Ultrasound, CT scan, and fistulography are three imaging modalities that can be used to help characterize a enterocutaneous fistula. Small bowel follow-through and endoscopy studies may also be helpful. Imaging is important for determining whether or not all of the fluid traveling through the fistula is coming out of the external opening. In some cases, fluid can be partially leaking into the abdomen and can then lead to the formation of an abscess. CT scan with oral contrast is considered the single best radiologic test since it can identify the tract, abdominal leaking, intra-abdominal abscesses, distal obstruction, and foreign bodies. Fistulography is used less often but can be useful when CT or ultrasound is unavailable or inconclusive. It is performed by injecting contrast into the external opening of the enterocutaneous fistula and taking plain film radiographs of the area.

Enterocutaneous fistula treatment

The first step in patient management is stabilization. Patients are at a high risk for electrolyte imbalances, sepsis, and malnutrition. Controlling all three of these factors is essential for survival. Electrolyte abnormalities and fluid balance need to be monitored closely because these patients can develop severe derangements quickly. Electrolyte losses vary depending on the location of the fistula in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract and the amount of output. Any deficiencies need to be replaced. In septic patients, a source needs to be identified and appropriately treated. Sepsis is documented as being responsible for two-thirds of mortality in these patients. Intra-abdominal abscesses are common and should be high on the differential as the source of sepsis. The Surviving Sepsis Campaign guidelines should be followed when treating these patients. Most patients will need parenteral nutrition, but a subset of patients may be able to tolerate an enteral elemental diet if the fistula is distal in the gastrointestinal tract and the output from the fistula is not increased by starting feeds. Either way, adequate nutrition is a well-established, essential component to treat these patients properly. Another important variable to stabilize is the output from the fistula. The fluid needs to be properly contained as not to damage the surrounding skin and to increase odds of healing. Various methods of wound care can aid in preventing skin loss, minimizing pain, and allowing the patient to function on a daily basis. Such strategies are typically similar to ostomy bag appliances, but some will require a more customized plan for containing the fistula output.

A decision then needs to be made on how to treat the gastrointestinal itself. There are some cases in which immediate surgical correction may be appropriate, but the majority of fistulas are treated non-operatively. This is because 90% of fistulas close on their own within 5 weeks of medical management. Depending on the surgeon, 2 to 3 months of will be attempted before the surgical correction of a fistula is considered. This waiting period gives the fistula an appropriate amount of time to close spontaneously. It also decreases the morbidity and mortality of surgical correction. When initiating medical management, the factors mentioned in the previous section that promotes fistula development should be evaluated. All modifiable variables should be corrected to increased chances of spontaneous closure. Low-output fistulas are more likely to close than higher output fistulas. Longer fistula tract length is associated with a higher chance of closing.

The goal of medical management is to decrease gastrointestinal output and encourage spontaneous closure. Nasogastric tubes should be avoided. In high output fistulas, proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) and H2 blockers can be used to decrease gastric secretions. Antidiarrheals, such as loperamide, are also effective in reducing the output of high-output fistulas. Octreotide, a somatostatin analog, has been extensively studied for controlling fistula output. It has been shown to decrease output, increase spontaneous closure, and decrease hospital stay, but has never been shown to decrease mortality. If a fistula has over one liter per day of output, an octreotide trial can be attempted. After 72 hours if there is a significant reduction in volume, the medication can be continued.

If the gastrointestinal does not resolve with medical management, surgical management will then be considered. Operating on gastrointestinals is fraught with difficulties, and there is a high risk for recurrence. Surgical approach may be difficult due to previous surgeries and adhesions. The bowel must be run carefully, and extreme care must be taken to not cause any accidental enterotomies during lysis of adhesion and bowel mobilization. As long as the bowel looks healthy, the best option is to excise the fistula tract and resect a small amount of associated bowel followed by an anastomosis to reestablish bowel continuity. To decrease recurrence rate, one must make sure to close the fascia where the fistula tract was traversing. As long as medical management, proper nutrition, and an appropriate waiting time precede the operation, permanent resolution of an enterocutaneous fistula occurs in 80% to 95% of cases.

Enterocutaneous fistula surgery

Enterocutaneous fistula prognosis

Enterocutaneous fistula is a common condition in most general surgical wards. Mortality has fallen significantly since the late 1980s, from as high as 40-65% to as low as 5-20%, largely as a result of advances in intensive care, nutritional support, antimicrobial therapy, wound care, and operative techniques 11. Even so, the mortality is still high, in the range of 30-35%, in patients with high-output enterocutaneous fistulas.

Once a patient develops an enterocutaneous fistula, the morbidity associated with the surgical procedure or the primary disease increases, affecting the patient’s quality of life, lengthening the hospital stay, and raising the overall treatment cost. Malnutrition, sepsis, and fluid electrolyte imbalance are the primary causes of mortality in patients with an enterocutaneous fistula.

Another factor that may be a predictor for poor healing outcomes is psoas muscle density, which can reflect sarcopenia 12. Assessment of psoas muscle density can identify patients with enterocutaneous fistula who will have poorer outcomes, and these patients may benefit from additional interventions and recovery time before operative repair.

If sepsis is not controlled, progressive deterioration occurs and patients succumb to septicemia. Other sepsis-related complications include intra-abdominal abscess, soft-tissue infection, and generalized peritonitis 13.

However, patients with an enterocutaneous fistula with favorable factors for spontaneous closure have a good prognosis and a lower mortality.

Favorable factors for spontaneous closure

Spontaneous closure of an enterocutaneous fistula is determined by certain anatomic factors. Fistulas that have a good chance of healing include the following:

- End fistulas (eg, those arising from leakage through a duodenal stump after Pólya gastrectomy)

- Jejunal fistulas

- Colonic fistulas

- Continuity-maintained fistulas – These allow the patient to pass stool

- Small-defect fistulas

- Long-tract fistulas

In addition, a fistulous tract of more than 2 cm has a higher possibility of spontaneous closure. Spontaneous closure is also possible if the bowel-wall disruption is partial and other factors are favorable. If the disruption is complete, surgical intervention is necessary to restore intestinal continuity.

Unfavorable factors for spontaneous closure

When an enterocutaneous fistula is associated with adverse factors, then spontaneous closure does not commonly occur, and surgical intervention, despite its associated risks, is frequently required. In these patients, the outcome is less likely to be good 14.

Factors preventing the spontaneous closure of an enterocutaneous fistula can be remembered by using the acronym FRIEND, which represents the following 6:

- Foreign body

- Radiation

- Inflammation/infection/inflammatory bowel disease

- Epithelialization of the fistula tract

- Neoplasm

- Distal obstruction – A distal obstruction prevents the spontaneous closure of an enterocutaneous fistula, even in the presence of other favorable factors; if present, surgical intervention is needed to relieve the obstruction

In addition, lateral duodenal, ligament of Treitz, and ileal fistulas have less tendency to spontaneously close 13.

- Singh H, Mandavdhare H, Sharma V. All that fistulises is not Crohn’s disease: Multiple entero-enteric fistulae in intestinal tuberculosis. Pol Przegl Chir. 2019 Jan 03;91(1):35-37.[↩]

- Cowan KB, Cassaro S. Fistula, Enterocutaneous. [Updated 2019 Jun 4]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2019 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459129[↩][↩]

- Chang J, Li CC, Achtari M, Stoufi E. Crohn’s disease initiated with extraintestinal features. BMJ Case Rep. 2019 Apr 20;12(4).[↩]

- Enterocutaneous Fistula Treatment & Management. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1372132-treatment[↩]

- Sunday-Adeoye I, Eni UE, Ekwedigwe KC, Isikhuemen ME, Daniyan BC, Yakubu EN, Eliboh MO, Uguru IE. Enterocutaneous Fistula Coexisting with Enterovesical Fistula: A Rare Complication of Ovarian Cystectomy. Afr J Reprod Health. 2019 Mar;23(1):139-149.[↩]

- Prickett D, Montgomery R, Cheadle WG. External fistulas arising from the digestive tract. South Med J. 1991 Jun. 84(6):736-9.[↩][↩]

- Berry SM, Fischer JE. Classification and pathophysiology of enterocutaneous fistulas. Surg Clin North Am. 1996 Oct. 76(5):1009-18.[↩]

- Tong CY, Lim LL, Brody RA. High output enterocutaneous fistula: a literature review and a case study. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2012. 21(3):464-9.[↩]

- Campos AC, Andrade DF, Campos GM, et al. A multivariate model to determine prognostic factors in gastrointestinal fistulas. J Am Coll Surg. 1999 May. 188(5):483-90.[↩]

- Williams LJ, Zolfaghari S, Boushey RP. Complications of enterocutaneous fistulas and their management. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2010 Sep. 23(3):209-20.[↩]

- Dudrick SJ, Maharaj AR, McKelvey AA. Artificial nutritional support in patients with gastrointestinal fistulas. World J Surg. 1999 Jun. 23(6):570-6.[↩]

- Lo WD, Evans DC, Yoo T. Computed Tomography-Measured Psoas Density Predicts Outcomes After Enterocutaneous Fistula Repair. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2018 Jan. 42 (1):176-185.[↩]

- Evenson AR, Fischer JE. Current management of enterocutaneous fistula. J Gastrointest Surg. 2006 Mar. 10(3):455-64.[↩][↩]

- Martinez JL, Luque-de-León E, Ballinas-Oseguera G, Mendez JD, Juárez-Oropeza MA, Román-Ramos R. Factors predictive of recurrence and mortality after surgical repair of enterocutaneous fistula. J Gastrointest Surg. 2012 Jan. 16 (1):156-63; discussion 163-4.[↩]