What is ependymoma

Ependymoma is a type of brain tumor that begins in cells lining the spinal cord central canal (fluid-filled space down the center) or the ventricles (fluid-filled spaces) of the brain, collectively called the central nervous system (CNS). Ependymomas occur in both children and adults. Ependymomas in the lower half of the brain are more common among children. Ependymomas in the spine are more common among adults. Ependymomas occur slightly more often in males than females. Ependymomas constitute approximately 2-5% of adult intracranial gliomas and up to 10% of childhood central nervous system (brain and spinal cord) tumors 1. Ependymomas are the third most common brain tumor in children. About 30% of pediatric ependymomas are diagnosed in children younger than 3 years of age and then again at age 34 years.

Ependymomas can form anywhere in the central nervous system (CNS). Ependymomas often occur near the ventricles in the brain and the central canal of the spinal cord. On rare occasions, ependymomas can form outside the central nervous system (brain and spinal cord), such as in the ovaries. Ependymomas develop from ependymal cells (called radial glial cells). Ependymal cells are one of three types of glial cells that support the central nervous system (CNS).

Ependymomas rarely spread outside the brain and spinal cord. But ependymomas can spread to other areas of the central nervous system through cerebrospinal fluid (CSF).

The first step of ependymoma treatment is to remove as much of the ependymoma tumor as possible. Radiation is usually recommended for older children and adults following surgery, in some cases even if the ependymoma tumor was completely removed.

The role of chemotherapy in treating newly diagnosed ependymomas is not clear. However, it may be used to treat ependymoma tumors that have grown back after radiation therapy, or to delay radiation in infants and very young children.

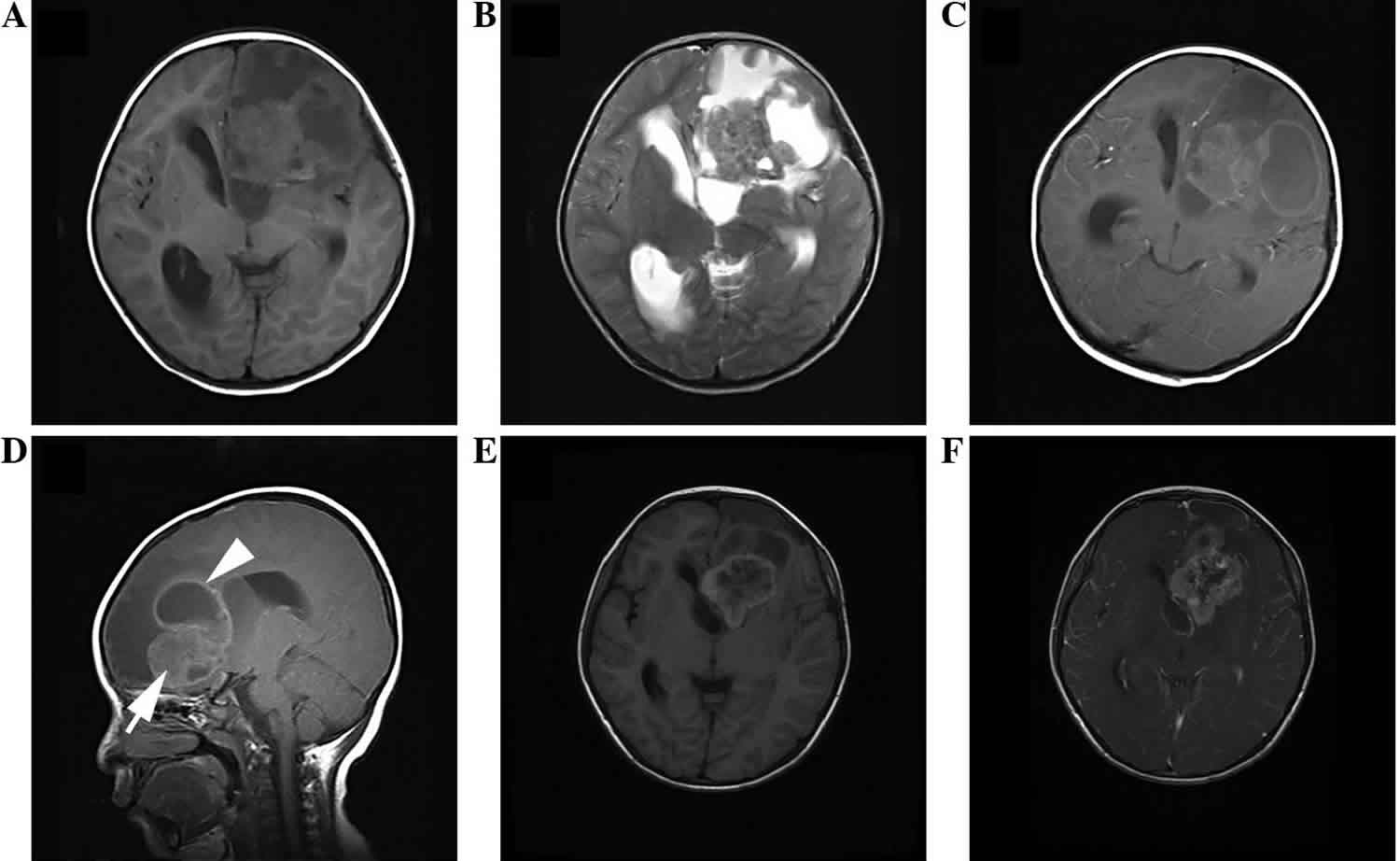

Figure 1. Anaplastic ependymoma

Footnote: Anaplastic ependymoma of the left temporal occipital lobe in a 54-year-old male. (A) Axial T1WI demonstrating an irregularly-lobulated hypointense mass. (B) Axial T2WI shows the heterogeneity of the lesion with hypointense, isointense and hyperintense (arrow) areas, with moderate peritumoral edema (arrowhead). (C) Axial and (D) coronal post-contrast T1WI demonstrating marked wreathlike enhancement with a thick wall. (E) Axial diffusion-WI showing moderate restriction of the tumor. (F) Axial T2WI displaying slightly patchy hyperintense (arrow).

Abbreviation: WI = weighted imaging.

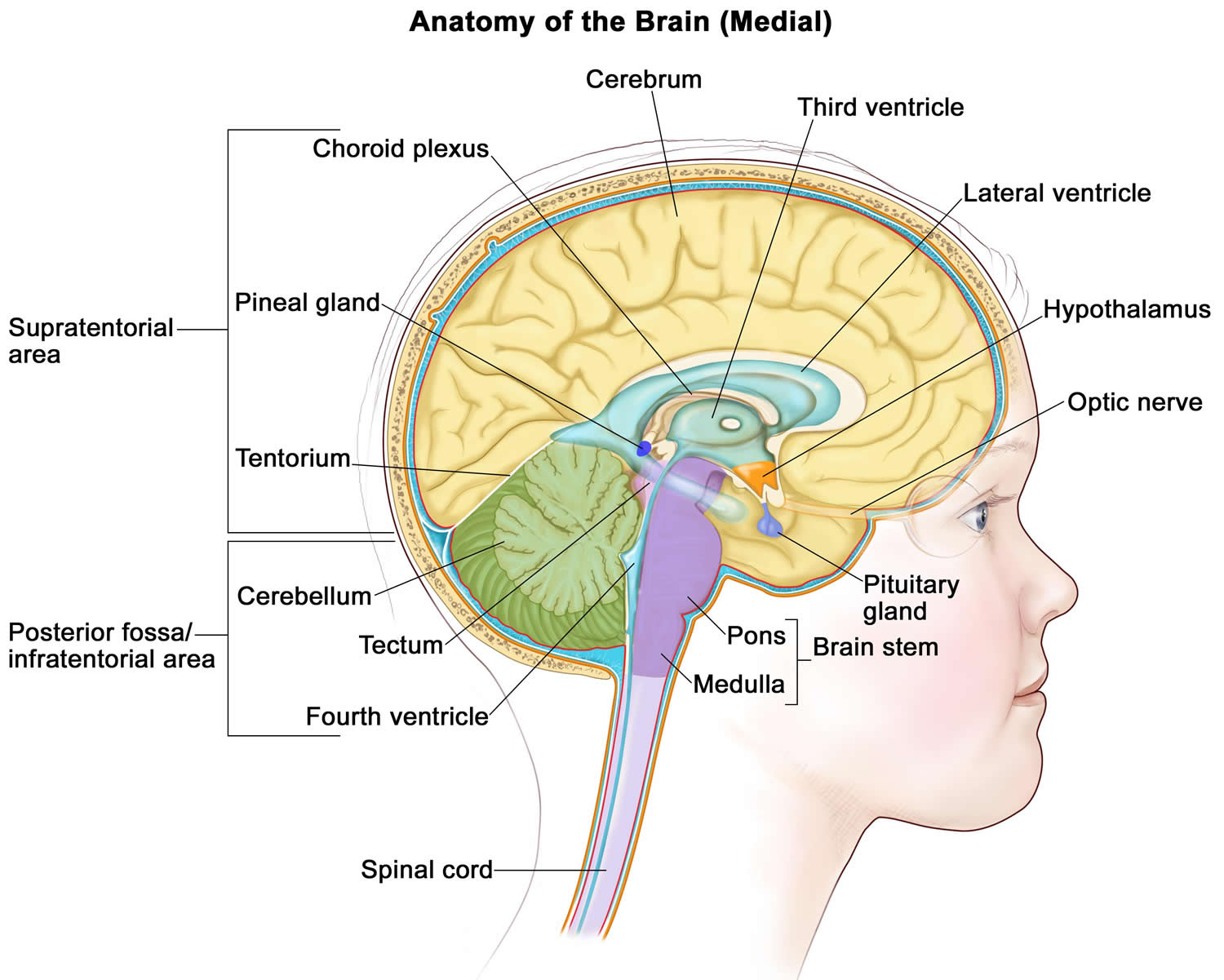

[Source 2 ]Figure 2. Brain anatomy

Ependymoma grades

Ependymomas are grouped in three grades based on their characteristics. Within each grade, are different ependymoma subtypes. Molecular testing is used to help identify subtypes that are related to location and disease characteristics.

- Grade 1 ependymomas are low grade tumors. This means the tumor cells grow slowly. The subtypes include subependymoma and myxopapillary ependymoma. Both are more common in adults than in children. Myxopapillary tumors usually occur in the spine.

- Subependymomas: Typically slow-growing tumors.

- Myxopapillary ependymomas: Typically slow-growing tumors.

- Grade 2 ependymomas are low grade tumors and can occur in either the brain or the spine. Ependymomas grade 2 is the most common of the ependymal tumors. Ependymomas grade 2 type can be further divided into the following subtypes, including cellular ependymomas, papillary ependymomas, clear cell ependymomas, and tancytic ependymomas.

- Grade 3 ependymomas are malignant (cancerous) ependymomas. This means they are fast-growing ependymoma tumors. The subtypes include anaplastic ependymomas. These most often occur in the brain, but can also occur in the spine. Anaplastic ependymomas are malignant in terms of their biological behavior, and patients with anaplastic ependymomas are at high risk of metastasis and relapse, which are responsible for the poor prognosis 3. A combination of surgery, radiation therapy and chemotherapy can improve the patient outcome 4.

Ependymomas are classified as either differentiated (low-grade or grade 2) or anaplastic (malignant or grade 3) tumors. Most are cellular tumors consisting of uniform polygonal cells in a collagenous background with well-defined cytoplasmic borders. Ependymomas are soft, grayish, or red tumors which may contain cysts or mineral calcifications and occasional hemorrhage. Some groups of cells form clusters around a circumscribed central space (ependymal rosette). Anaplastic ependymomas have features that resemble glioblastoma multiforme. Glioblastoma multiforme may have high mitotic activity, endothelial proliferation, and necrosis. A very highly cellular, embryonal form of ependymal tumor occurring in infants and children younger than age 5 years is the ependymoblastoma 5. Ependymoblastoma is biologically and pathologically distinct from the other types of ependymomas. The ependymoblastoma often disseminates along the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) pathways and requires irradiation of the craniospinal axis. Children with ependymoblastoma rarely live more than 2 to 3 years. Ependymoblastomas are most likely a form of PNET (Primitive Neuro Ectodermal Tumors) with ependymal differentiation, and are treated in the same fashion as medulloblastoma. This variant of ependymoma should be regarded as distinct from malignant (anaplastic) ependymoma in terms of treatment.

Ependymoma causes

The cause of ependymomas is not known. Ependymomas are tumors that resemble normal ependymal cells and tend to occur along the surfaces of the ventricles. They may also occur in the parenchyma adjacent to the ventricle or anywhere along the entire length of the spinal canal and the filum terminale. More than 60% of ependymomas occur infratentorially, most of which occur in the posterior fossa, and arising predominantly from the fourth ventricle. Most supratentorial ependymomas are parenchymal rather than intraventricular in location, and occur most frequently in the frontal and parietal lobes. Tumor extension may occur along the leptomeninges, around the medulla and upper cervical cord to the conus, and along nerve roots; ependymal cells may be found in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF).

Ependymoma symptoms

Symptoms related to an ependymoma depend on the tumor’s location and size. In babies, increased head size may be one of the first symptoms. Irritability, sleeplessness, and vomiting may develop as the tumor grows. In older children and adults, nausea, vomiting, and headache are the most common symptoms.

Clinically, patients may present with subtle signs and symptoms for years before the diagnosis is made or may present abruptly with obstructive hydrocephalus or an expanding ependymoma of the spinal cord. Other focal findings include visual field defects, focal seizures, headache, nausea, and vomiting.

People with an ependymoma in the brain may have headaches, nausea, vomiting and dizziness. People with an ependymoma in the spine may have back pain, numbness and weakness in their arms, legs or trunk, problems with sexual, and urinary or bowel problems.

Ependymoma location

The various types of ependymomas appear in different locations within the brain and spinal column. Subependymomas usually appear near a ventricle. Myxopapillary ependymomas tend to occur in the lower part of the spinal column. Ependymomas are usually located along, within, or next to the ventricular system. Anaplastic ependymomas are most commonly found in the brain in adults and in the lower back part of the skull (posterior fossa) in children. They are rarely found in the spinal cord.

Ependymoma diagnosis

The neuroimaging of ependymomas is nonspecific, but some findings are useful that suggest the diagnosis, including calcification associated with a fourth ventricular tumor. They tend to extend out of the fourth ventricle into the cerebellum, foramen magnum, cerebellopontine angle, and upper cervical arachnoid space. The MRI appearance of ependymomas is heterogeneous. The solid portions are hypointense on T1WI and hyperintense on T2WI. Almost all ependymomas are contrast enhancing, although the enhancement is often irregular and patchy. Intratumoral cysts are more common in supratentorial ependymomas and usually have slightly higher intensity signal than CSF on T1WI. Because many lesions may be confused with ependymomas (such as primitive neuroectodermal tumors [PNETs]), treatment should not proceed without histologic verification of the tumor and an assessment of the degree of anaplasia.

Ependymoma treatment

The first treatment for an ependymoma is surgery, if possible. The goal of surgery is to obtain tissue to determine the tumor type and to remove as much tumor as possible (gross total resection) without causing more symptoms for the person. Unfortunately, extensive resection is often impossible, particularly for lesions of the posterior fossa or for spinal cord ependymomas involving the cauda equina. Supratentorial lesions are more amenable to gross total resection. In patients older than age 3 years with gross total resections of low-grade nondisseminated ependymomas, deferring further adjuvant therapy may be a viable option. In one study, all 5 patients with the above tumor profile were alive after a median follow-up of 44 months, with a median progression-free survival over 38 months.178 Low-grade ependymoma of the spine may be managed with surgery alone if the resection is complete. Staging is a critical aspect in the management of ependymomas. This involves an MRI of the brain and the entire spinal cord with contrast, as well as CSF cytology to rule out neuraxis dissemination.

After surgery, there is no standard treatment for ependymomas. Many people won’t need other treatment after surgery. For other people, treatments may include radiation, chemotherapy or clinical trials. Clinical trials, with new chemotherapy, targeted therapy, or immunotherapy drugs, may also be available and can be a possible treatment option. Treatments are decided by the patient’s healthcare team based on the patient’s age, remaining tumor after surgery, tumor type, and tumor location.

Several retrospective series strongly suggest an advantage to the addition of radiation therapy in improving survival 6. In the series by Ernestus and colleagues 7, patients with supratentorial grade 2 ependymomas treated with radiation had a median survival 185 months. The benefit of postoperative irradiation was even more striking in patients who underwent only a partial resection: the median disease-free survival was 9 months in patients undergoing surgery only, but was more than 108 months in those who received postoperative radiation therapy. Survival was only 21 months for those with grade 3 tumors despite irradiation. Other trials have documented the radiosensitivity of ependymomas. The literature does not identify, however, the optimal perimeters of the radiation field for treating ependymomas in specified locations or whether the craniospinal axis should always be included in the field. The risk of spinal subarachnoid metastasis is greatest with infratentorial anaplastic ependymomas (approximately 30%) and is least likely with supratentorial low-grade ependymomas (5% to 10%). There is also a risk of intraventricular and intracranial spread from a malignant supratentorial lesion. For these reasons, the extent of the irradiated field is an important issue. Salazar and colleagues reported a local control rate of 12% using small-volume fields, as compared to 78% control with whole-brain irradiation in a group of patients with low-grade ependymomas 8. The 5-year survival rate was 12% with partial-brain and 67% with whole-brain treatment. Other series show no benefit to craniospinal irradiation 9. Because the primary site of recurrence of both low- and high-grade ependymomas is usually within the local radiation field, whole-brain or craniospinal irradiation is probably not indicated. Staging is a critical aspect in the management of ependymomas. The consensus management approach is to give focal irradiation after maximal resection to the resection cavity and to the surrounding tissue area, rather than craniospinal axis irradiation if there is no evidence of dissemination.

Chemotherapy unfortunately has only a minor role in these tumors, and may be most useful in the treating of recurrent ependymoma. Adjuvant chemotherapy does not improve overall survival in ependymoma patients. Despite their frequent posterior fossa location, ependymomas, unlike PNETs, are fairly chemoresistant. These tumors are occasionally sensitive to several agents, including the nitrosoureas and platinum compounds. A Center for Cancer Genomics study randomized pediatric patients with newly diagnosed posterior fossa ependymomas into two groups: those who received craniospinal axis irradiation, and those who received craniospinal axis irradiation and an adjuvant chemotherapy regimen of Lomustine (CCNU), vincristine, and prednisone for 1 year. There was no difference in outcome between the two groups, suggesting that this chemotherapy regimen does not improve survival of infratentorial ependymoma patients.184 Much more research is needed to find new agents to treat ependymoma.

Ependymoma prognosis

One of the most important ependymoma prognostic variables is the amount of residual tumor after resection 9. Children with low-grade nondisseminated ependymomas that have been completely resected have the best prognosis, whereas incomplete resection or dissemination carries a poor prognosis. The retrospective series by Horn and colleagues 9 evaluated the outcome of 83 children with ependymoma treated at 11 institutions between the years 1987 and 1991. This is an important contemporary review and the data is useful as a baseline from which to compare new trials. In this review, the overall survival at 5 and 7 years was 57% and 46%, respectively; event-free survival for the same periods was 42% and 33%. Patients younger than age 3 years had significantly worse outcome. Univariate analysis revealed that young age, subtotal resection, and grade 3 histology were important adverse risk factors for event-free survival. Overall survival was negatively influenced by the same factors, with high-grade histology having only borderline significance in a multivariate analysis. Most patients (89%) progressed at the original tumor location. Adjuvant chemotherapy or craniospinal axis irradiation did not significantly influence outcome. The authors concluded that improvement of local control is an important goal for future studies.

There are conflicting data concerning the prognostic implications of anaplasia in these tumors 10. Ross and Rubinstein reviewed a series of 15 patients classified as having anaplastic ependymomas (excluding cases of ependymoblastoma) in an attempt to correlate pathology with survival; postoperative survival was not found to correlate with anaplastic histology. The median survival for 10 patients with malignant tumors was 8.8 years; 5 patients who had tumor recurrence died within 13 months to 6 years (median 2.5 years). In their review, Horn and colleagues 9 found World Health Organization (WHO) grade 3 histology a significant adverse risk factor for overall survival and event-free survival in univariate analyses, but only of borderline significance in overall survival when correcting for other factors, such as extent of disease 9.

- Pan E, Prados MD. Ependymoma. In: Kufe DW, Pollock RE, Weichselbaum RR, et al., editors. Holland-Frei Cancer Medicine. 6th edition. Hamilton (ON): BC Decker; 2003. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK13559[↩]

- Leng, X., Tan, X., Zhang, C., Lin, H., & Qiu, S. (2016). Magnetic resonance imaging findings of extraventricular anaplastic ependymoma: A report of 11 cases. Oncology Letters, 12, 2048-2054. https://doi.org/10.3892/ol.2016.4825[↩]

- Martínez León MI, Denis Vidal M and Lara Weil B: Magnetic resonance imaging of infratentorial anaplastic ependymoma in children. Radiologia. 54:59–64. 2012.[↩]

- Shim KW, Kim DS and Choi JU: The history of ependymoma management. Childs Nerv Syst. 25:1167–1183. 2009.[↩]

- Mork SJ , Rubinstein LJ . Ependymoblastoma. A reappraisal of a rare embryonal tumor. Cancer. 1985;55:1536–42.[↩]

- Shaw EG , Evans RG , Scheithauer BW . et al. Postoperative radiotherapy of intracranial ependymoma in pediatric and adult patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1987;13:1457–62.[↩]

- Ernestus RI , Wilcke O , Schroder R . Intracranial ependymomas: prognostic aspects. Neurosurg Rev. 1989;12:157–63.[↩]

- Salazar OM , Castro-Vita H , VanHoutte P . et al. Improved survival in cases of intracranial ependymoma after radiation therapy. Late report and recommendations. J Neurosurg. 1983;59:652–9.[↩]

- Horn B , Heideman R , Geyer R . et al. A multi-institutional retrospective study of intracranial ependymoma in children: identification of risk factors. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 1999;21:203–11.[↩][↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Robertson PL , Zeltzer PM , Boyett JM . et al. Survival and prognostic factors following radiation therapy and chemotherapy for ependymomas in children: a report of the Children’s Cancer Group [see comments] J Neurosurg. 1998;88:695–703.[↩]