What is erythema nodosum

Erythema nodosum is a skin condition that produces red bumps under the skin that can be tender, usually on your lower legs and less commonly the thighs and forearms. Erythema nodosum happens when the layer of fat that everybody has under their skin becomes inflamed or irritated (panniculitis). Erythema nodosum is sometimes caused by some underlying disease or use of a medication, but about half the time there is no reason for it. The bumps of erythema nodosum can occur anywhere on the body but are most common on the shins. They look like raised bumps or bruises that change from pink to blue-brown. While the rash can be painful, it is harmless in itself. Erythema nodosum usually settles down without specific treatment over several weeks.

Erythema nodosum can be triggered by:

- a reaction to medicines such as the contraceptive pill or a sulfur-containing medication

- a throat infection

- pregnancy

Erythema nodosum can also come on in people who have:

- inflammatory bowel disease such as Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis

- tuberculosis and other infections

- sarcoidosis

But in about half of all people who get it, doctors can’t identify the cause.

How is erythema nodosum treated?

Your doctor will treat any illness that is causing erythema nodosum.

General treatment for erythema nodosum might include:

- anti-inflammatory medicine like ibuprofen (some people can’t take these – check with your doctor if unsure)

- support stockings or bandages

- resting, especially if your legs are sore and swollen

- raising your feet and legs

- cold packs

The bumps and patches last about two weeks before fading like a bruise. Most people find their erythema nodosum clears up in 2 to 4 weeks, without any need for medicine.

Although erythema nodosum may occur on its own, it is more often associated with a medication or with an underlying infection or medical condition (see causes below). Therefore, it is important to see your doctor in order to investigate any possible health problems.

Generally, people with erythema nodosum do quite well, especially once any underlying medical conditions have been treated.

Since erythema nodosum can be associated with underlying infections or health problems, a physician should be consulted within a few days of noticing the skin lesions.

Who’s at risk of erythema nodosum?

Erythema nodosum can occur in patients of any age, sex, or race. Erythema nodosum is most common in females (women are affected three to six times more than men), particularly in women between 25 and 40 years 1. In addition, erythema nodosum tends to occur in families who are exposed to the same trigger. While their cause to a particular individual may be unknown, people who receive immunity-weakening drugs (e.g., chemotherapy drugs), oral contraceptives, and antibiotics are more likely to develop them. Also, infections and cancers can predispose a person to developing erythema nodosum.

Most people with erythema nodosum are otherwise in good health but it is often associated with recent infection or illness.

What does erythema nodosum look like?

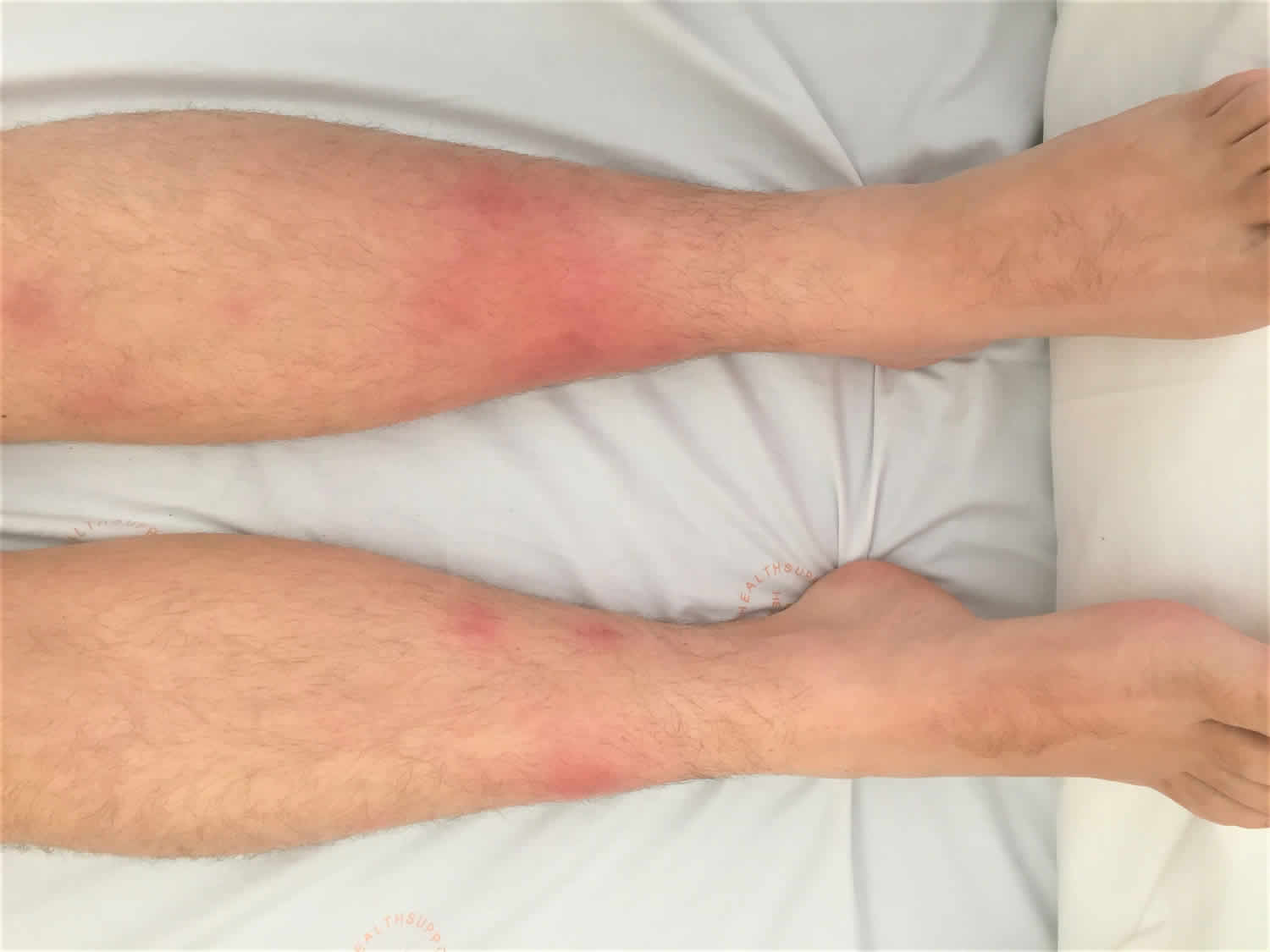

Erythema nodosum is characterised by the sudden development of red, painful nodules over the shins and/or lower legs. At first, the lesions are a bright red colour and are raised above the skin. After 1 to 2 weeks, they flatten and become a darker red/purple color. The nodules usually do not form pus and do not ulcerate. They usually heal without scarring. Leg ache and ankle swelling are common in the initial phase. In rare cases, other sites such as upper thighs, upper arms and face can be involved. Other symptoms can include fever, lethargy, abdominal pain, diarrhea and joint pain.

Figure 1. Erythema nodosum

Erythema nodosum causes

Erythema nodosum is considered to be a hypersensitivity response to different provoking agents. This leads to activation of the immune system and inflammation of the fat layer in the skin.

The condition can be triggered by a wide variety of stimuli such as previous streptococcal throat infection, pregnancy, tuberculosis, medications, inflammatory bowel disease (ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease), sarcoidosis and rarely malignancy. Less common causes include infection such as Yersinia enterocolitica and Mycoplasma. Various drugs (such as the oral contraceptive pill, salicylates, sulphonamide drugs, iodine/bromide and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) may also precipitate the condition. However, more than fifty per cent of cases have no identifiable cause.

Common causes of erythema nodosum are:

- Idiopathic: No obvious etiology have been found in about 30% to 50% of published cases

- Throat infections; these may be due to streptococccus or viral in origin.

- Other bacterial infections, such as Mycoplasma pneumoniae.

- Sarcoidosis; erythema nodosum is often associated with enlargement of the lymph nodes (bihilar lymphadenopathy) in the lungs in sarcoidosis. This is known as Löfgren syndrome. It may result in a dry cough or some shortness of breath.

- Tuberculosis (TB); erythema nodosum occurs with the primary infection with tuberculosis. Tuberculosis in the United States is currently uncommon.

- Pregnancy or the oral contraceptive pill; erythema nodosum may occur after the first 2 or 3 cycles on the pill. Erythema nodosum may occur in pregnancy, clear after delivery, then recur in subsequent pregnancies.

- Other drugs; other drugs which have been reported to cause erythema nodosum include: sulfonamides, saliclyates, other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), bromides, iodides and gold salts.

- Inflammatory bowel disease (ulcerative colitis or Crohn disease)

- Other causes; there are many other causes of erythema nodosum but these are uncommon in the US.

Erythema nodosum leprosum is a particular variant of erythema nodosum that affects some people being treated for leprosy, and is more usually called type 2 lepra reaction.

Infections

Bacterial

- Streptococcal infections-most common infectious etiology commonly streptococcal pharyngitis(28-48%)

- Chlamydia

- Syphilis

- Coccidioidomycosis

- Tuberculosis

- Mycobacteria

- Leprosy

- Yersinia species (in Europe), salmonella, campylobacter gastroenteritis

- Mycoplasma pneumonia

- Tularemia

- Cat scratch disease (Bartonella species)

- Leptospirosis

- Brucellosis

- Psittacosis

- Chlamydia trachomatous

- Lymphogranuloma venereum

- Histoplasmosis

- Psittacosis

Viral

- Infectious mononucleosis

- Hepatitis B, Hepatitis C

- Human immunodeficiency virus(HIV)

- Herpes simplex virus(HSV)

- Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) or mononucleosis

- Para vaccinia

Fungal

- Coccidioidomycosis

- Histoplasmosis

- Blastomycosis

Parasitic

- Amebiasis

- Giardiasis

Non infectious causes

Drugs

- Antibiotics- penicillins, sulfonamides

- Miscellaneous drugs- Oral contraceptives, bromides, iodides, TNF-alpha inhibitor

Cancer

- Leukemia

- Lymphoma

- Occult malignancies

Inflammatory Bowel Disease

- Crohn’s disease

- Ulcerative colitis

Other causes

- Sarcoidosis-Lofgren’s syndrome(triad of erythema nodosum, acute arthritis, and hilar lymphadenopathy)

- Pregnancy

- Whipple disease

- Behcet disease

Erythema nodosum sarcoidosis

Sarcoidosis is the second most common cause of erythema nodosum 2. Skin eruptions in the course of sarcoidosis are observed in 25% of patients. Often the lesions are symmetrical on the extensor surface of both lower limbs. Other skin lesions, predominantly chronic, are lupus pernio, maculopapular lesions, sarcoid discs and scars 3.

Coincidence of such a triad of symptoms as erythema nodosum, arthritis and hilar lymphadenopathy in the course of sarcoidosis is called Löfgren syndrome. This syndrome is usually the early stage of sarcoidosis, which has an acute course and a good prognosis. It is important to remember that the enlargement of the hilar lymph nodes is not specific for Löfgren syndrome and can also occur in such diseases as lymphoma, tuberculosis, coccidioidomycosis, histoplasmosis or acute infections caused by Chlamydia pneumoniae 4.

As proven recently, occurrence of erythema nodosum in sarcoidosis is related to polymorphism in the promoter region of the TNF gene in the 308th position of both sexes 2. Additionally, women demonstrated an association with polymorphism of intron 1 in the tumor necrosis factor β (TNF-β) gene (lymphotoxin α) – located adjacent to the TNF-α gene. It is also worth mentioning that oestradiol takes part in up-regulation of TNF, which can potentially be an important factor determining the frequency of developing of erythema nodosum between the genders. Confirmation of the hypothesis may be the fact that erythema nodosum occurs with the same frequency in men and women in the prepubertal period. Considering the role of TNF-α, it is possible that monoclonal antibody directed against this cytokine may be effective in sarcoidosis treatment 5.

It is considered that biopsy confirmation in patients presenting with classical Löfgren syndrome with symmetrical bilateral hilar adenopathy is usually not necessary. On the other hand, if there is asymmetrical hilar adenopathy or clinical suspicion of either malignancy or tuberculosis, a histopathological examination should be undertaken 6. To distinguish skin lesions taking tuberculosis into consideration, the QuantiFERON-TB Gold assay can be used, as it is characterized by high sensitivity and specificity, and it detects the MTB antigen-specific interferon γ (IFN-γ) 7.

The use of systemic steroids is a matter of debate and should be considered if underlying conditions such as infection or malignancy have been excluded. Oral prednisone at a dosage of 60 mg every morning is a typical dose (a general rule is 1 mg per kg per day). Patients should be treated until complete resolution of skin lesions 8.

Furthermore, our clinical experience has shown that if the chest radiography is within normal limits but there is a clinical suspicion of sarcoidosis, high-resolution chest computed tomography should be performed. High-resolution chest computed tomography provides better diagnostic performance of lung alterations such as hilar adenopathy or nodular infiltrates compared to chest X-ray.

Erythema nodosum and pregnancy

The high incidence of erythema nodosum in females suggests that it is related to sex hormones, confirmed by the more frequent occurrence during pregnancy and when using oral contraceptive pills. Erythema nodosum occurs among 4.6% of pregnant women 8.

The role of sex hormones in the aetiopathology of erythema nodosum and its influence on the immunological system are not sufficiently known. Contraceptive pills were described as the most common drug causing erythema nodosum, and reduced incidence of erythema nodosum after the 1980s was observed, when low-oestrogen contraceptive drugs were introduced 9.

One mechanism of estrogens’ influence on the immunological system is modulating it to increase the production of cytokines by T-cells and macrophages. In vitro research on mouse models showed that the supply of estrogens results in an increasing number of cells producing inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin 10 (IL-10) and IL-6. It confirmed the earlier research by Dayan et al. 10 which revealed that the use of tamoxifen and anti-estrogens leads to elevated levels of IL-2 and IFN-γ and to decreased levels of IL-10, IL-1 and TNF-α.

Some researchers argue that more important than the levels of estrogens and progesterone in the cause of erythema nodosum are the proportions of these two hormones, as there has been no description of any cases of erythema nodosum among women treated with high-dose estrogens therapy in breast cancer treatment. Erythema nodosum usually occurs in the first trimester of pregnancy when the level of progesterone is lower than in the next stage of gestation. Administration of tamoxifen and anti-estrogens such as aromatase inhibitors was associated with occurrence of the erythema nodosum 9. This raises the suspicion that it may have a correlation with the aforementioned elevated level of IFN-γ, caused by use of tamoxifen, which takes part in the inflammatory response with formation of granuloma, as it happens in erythema nodosum 11. Interferon γ plays a role in gestation as well, where it is produced by NK cells of the uterus, leading to dilatation and thickening of spiral arteries in order to provide the best nutrition to the fetus 12.

Occurrence of erythema nodosum in one of several gestations of the same woman or only once in many cycles of using contraceptive pills indicates that female sex hormones play mainly a role of modulators of the immune system, rather than directly impacting the pathomechanism of erythema nodosum.

Erythema nodosum cancer

Erythema nodosum may be the first sign of an existent neoplastic disease. Paraneoplastic erythema nodosum most often occurs with Hodgkin’s lymphoma, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and leukaemia, but it has also been linked to solid tumors 13. The pathogenesis of malignancy-associated erythema nodosum is unknown. It is suggested that paraneoplastic erythema nodosum is caused by an altered immune system response to a malignancy.

In cases associated with cancer, erythema nodosum coincides or appears shortly before the diagnosis of the neoplasm. Skin lesions which recur chronically or persist for a long time require exclusion of an underlying malignant disease. Clinical features such as weight loss, fever, age at onset over 50, poor response to treatment and atypical laboratory investigations (e.g. hypergammaglobulinaemia, long-lasting anaemia, thrombocytopenia) are helpful in distinguishing paraneoplastic erythema nodosum from non-neoplastic conditions. It is also known that erythema nodosum may indicate tumour relapse. For this reason, development of skin lesions in patients with previously treated malignancy requires oncological vigilance.

The early diagnosis of cancer in patients with paraneoplastic erythema nodosum is very important and can be achieved by complete medical history taking, physical examination and age-appropriate cancer screening. Skin lesions usually respond to treatment of underlying cancer. Unfortunately, malignancy-associated erythema nodosum is considered to be a marker of poor prognosis 13.

Erythema nodosum and inflammatory bowel disease

Skin disorders, after arthritis, uveitis and aphthous stomatitis, are one of the most common extra-intestinal manifestations of inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD). Erythema nodosum is the most common cutaneous manifestation in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases, occurring in 4–15% of Crohn’s disease cases and in 3–10% of ulcerative colitis cases 2. It is also more prevalent in women.

It is presumed that skin lesions of erythema nodosum correlate with the activity of bowel disease, and in patients with Crohn’s disease colonic involvement is observed more often 14.

Erythema nodosum usually parallels inflammatory bowel disease activity, although it may precede the diagnosis of inflammatory bowel diseases by up to five years. Treatment targeted at the underlying cause usually leads to resolution of the skin lesions 15.

There are some reports that erythema nodosum in patients with Crohn’s disease is associated with the T-cell immune response to common antigens of intestinal and skin bacteria. In addition, there are suggestions that genetic factors also play a role in the pathogenesis of skin lesions in inflammatory bowel diseases – mainly variants of the TRAF3IP2 gene encoding a protein involved in inflammatory reactions by activating cytokines. The presence of ANCA and HLA-B27 antigen in patients with erythema nodosum and inflammatory bowel disease also argues in favour of the important role of genetic factors 16.

Erythema nodosum differential diagnosis

- Non-suppurative infectious dermphypodermitis diagnosis is easy

- Nodular hypodermitis with vascular involvement (periarteritis nodosa, and superficial thrombophlebitis) and damage to deep vessels of medium to sometimes large diameter is associated with hypodermic septal or lobular involvement. Nodules can become necrotic. The diagnosis is primarily histological.

- Lobular hypodermitis or panniculitis involves lesions that are primarily greasy. The diagnosis is primarily histological, hence the absolute need for biopsy control. Several entities have been distinguished. The nodules can liquefy, fistulate, and leave a scar.

Erythema nodosum symptoms

Erythema nodosum appears as one or more reddish, warm, and painful lumps (nodules), ranging in size from 1–10 cm. Painful red lumps or nodules gradually appear on the skin over a period of up to 10 days. They usually appear on the legs, from the knees down. They can also appear on the thighs, arms or face. The lumps can be as small as a grape or as big as an orange. They gradually turn purple, like an old bruise, before fading away.

The most common locations for erythema nodosum include:

- Shins

- Knees, ankles, or thighs

- Forearms

- Face and neck

Other erythema nodosum symptoms can include:

- swollen legs

- fever

- feeling unwell or tired

- aching joints and muscles

The onset of erythema nodosum may be associated with fever, generalized achiness, leg swelling, or joint pain.

Individual nodules of erythema nodosum usually last from 1–2 weeks, but new lesions may continue to appear for up to 6 weeks. When an individual lesion of erythema nodosum has resolved, it may leave behind a temporary bruise, which subsequently fades to normal-appearing skin.

Erythema nodosum complications

Erythema nodosum is uncomfortable, but not dangerous in most cases. In most people, erythema nodosum resolve within 4 to 6 weeks. However, leg pain and swelling of the ankles may persist for weeks after this. Children usually have a shorter illness than adults.

Relapses tend to occur more commonly in those with erythema nodosum of unknown cause and erythema nodosum not associated with respiratory tract infections. Complications from erythema nodosum are highly uncommon.

Erythema nodosum diagnosis

Erythema nodosum is diagnosed by a doctor based on how the erythema nodosum bumps look and feel. Sometimes a biopsy (sample) of your skin is taken to make sure the diagnosis is right. If your doctor suspects that there is some other illness causing your erythema nodosum, they might ask you to have other tests.

Your doctor might order:

- complete blood count and C-reactive protein (CRP) and/or erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR)

- ASO (anti-streptolysin O) titer (a test for streptococcal infection)

- throat swab to test for streptococcal infection (test for group A streptococci)

- chest X-ray for tuberculosis

- phlegm test

- urine test

- stool culture to test for Yersinia enterocolitica

- calcium levels,

- ACE level (to test for sarcoidosis)

- Mantoux test or QuantiFERON gold (tests for active tuberculosis)

Erythema nodosum treatment

After diagnosing you with erythema nodosum, your doctor will attempt to identify a possible cause, such as medication, infection, or medical condition. The doctor may order diagnostic tests such as blood work, a chest X-ray, or a throat culture. If an underlying cause is identified, then your doctor will treat it appropriately (for example, by discontinuing a medication, prescribing antibiotics for an infection, or treating a health problem).

Once those investigations and treatments are under way, your health care provider may try the following measures to make you more comfortable:

- Restriction of physical activity or bed rest if pain and/or swelling is severe

- Firm supportive bandages or light compression stockings should be worn

- Anti-inflammatory medications such as ibuprofen (aspirin should NOT be given to any child aged 18 years or younger)

- Potassium iodide (SSKI) solution has been reported to be effective, most often given as drops added to orange juice, but is not easy to obtain.

- Oral tetracyclines have anti-inflammatory properties and may reduce discomfort and duration of disease

- Steroids (either taken in pill form or injected directly into the lesions)

Mild cases of erythema nodosum subside in 3 to 6 weeks. Cropping of new lesions may occur within this time, especially if the patient is not resting. Sometimes, erythema nodosum may become a chronic or persistent disorder lasting for 6 months and occasionally for years.

- Hafsi W, Badri T. Erythema, Nodosum. [Updated 2018 Oct 27]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2018 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470369[↩]

- Chowaniec M, Starba A, Wiland P. Erythema nodosum – review of the literature. Reumatologia. 2016;54(2):79-82. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4918048/[↩][↩][↩]

- Grzelewska-Rzymowska I. Sarkoidoza – choroba ogólnoustrojowa. Alergia. 2012;2:23–31[↩]

- Requena L, Sánchez YE. Erythema nodosum. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2007;26:114–122.[↩]

- McDougal KE, Fallin MD, Moller D, et al. the ACCESS Research Group Variation in the lymphotoxin-α/tumor necrosis factor locus modifies risk of erythema nodosum in sarcoidosis. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:1921–1926.[↩]

- Costabel U, Guzman J, Drent M. Diagnostic approach to sarcoidosis. Eur Respir Monograph. 2005;10:259–260[↩]

- Chen S, Chen J, Chen L, et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection is associated with the development of erythema nodosum and nodular vasculitis. PLoS One. 2013;8(5):e62653[↩]

- Schwartz RA, Nervi SJ. Erythema nodosum: a sign of systemic disease. Am Fam Physician. 2007;75:695–700.[↩][↩]

- Acosta KA, Haver MC, Kelly B. Etiology and therapeutic management of erythema nodosum during pregnancy: an update. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2013;14:215–220.[↩][↩]

- Verthelyir D. Sex hormones as immunomodulators in health and disease. International Immunopharmacology. 2001;6:983–993.[↩]

- Dayan M, Zinger H, Kalush F, et al. The beneficial effects of treatment with tamoxifen and anti-estradiol antibody on experimental systemic lupus erythematosus are associated with cytokine modulations. Immunology. 1997;90:101–108.[↩]

- Majkowska-Wojciechowska B. Zmiany układu immunologicznego wraz z wiekiem. Żywność dla Zdrowia. 2010;13:10–13.[↩]

- Sendur OF. Paraneoplastic rheumatic disorders. Turk J Rheumatol. 2012;27:18–23.[↩][↩]

- Huang BL, Chandra S, Shih DQ. Skin manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease. Front Physiol. 2012;3:1–6.[↩]

- Cowan JT, Graham MG. Evaluating the clinical significance of erythema nodosum. Patient Care. 2005:56–58.[↩]

- Faulkes RE. Upper limb erythema nodosum: the first presentation of Crohn’s disease. Clin Case Rep. 2014;2:183–185.[↩]