Excess sleepiness

Excessive sleepiness also known as excessive daytime sleepiness, is defined by having an increased pressure to fall asleep during typical wake hours 1. Excessive Daytime Sleepiness is a common complaint of many adults and children. It is the most common symptoms of people with sleep disorders. Excessive Daytime Sleepiness is a leading cause of fatalities from motor vehicle accident. Sleep problems contribute to more than 100,000 motor vehicle incidents that result in 71,000 personal injuries and 1,500 deaths annually 2. According to the National Transportation Safety Board, up to 52 percent of single vehicle crashes involving heavy trucks are fatigue-related, with the driver falling asleep in 17.6 percent of cases 3. Most sleep-related crashes involve adolescent and young adult male drivers 4. Sleepy adolescents also have significantly lower levels of academic performance, increased school tardiness, and lower graduation rates than other students 5. Daytime sleepiness has been linked to poor health on several standardized measurements, including impairment in all domains of the Medical Outcomes Study short form health survey (36 items) 6. It has also been associated with compromised professional performance, including that of physicians and judges 7. Reduced cognitive function related to excessive daytime sleepiness can affect the ability to gain or maintain employment, because patients with excessive daytime sleepiness may be misperceived as lazy or unmotivated.

Excessive Daytime Sleepiness is one of the most common sleep-related symptoms and it affects an estimated 20 percent of adults in the United States 8. People who have excessive sleepiness feel drowsy and sluggish most days, and these symptoms often interfere with their work, school, activities, or relationships. Although patients with excessive daytime sleepiness often complain of “fatigue,” excessive sleepiness is different from fatigue which is characterized by low energy and the need to rest (not necessarily sleep). Excessive sleepiness is also different from depression, in which a person may have a reduced desire to do normal activities, even the ones they used to enjoy. Persons with excessive daytime sleepiness are at risk of motor vehicle and work-related incidents, and have poorer health than comparable adults 9. The prevalence of excessive daytime sleepiness is highest in adolescents, older persons, and shift workers 10, but assessment of its true prevalence is difficult because of the subjective nature of the symptoms, inconsistencies in terminology, and a lack of consensus on methods of diagnosis and assessment. Some persons use subjective terminology (e.g., drowsiness, languor, inertness, fatigue, sluggishness) when describing symptoms of excessive daytime sleepiness 11.

Excessive sleepiness is not a disorder in itself, it is a serious symptom that can have many different causes. If you feel excessively sleepy, you and your doctor should investigate it further. The most common causes of excessive daytime sleepiness are sleep deprivation or poor sleep habits, such as reduced opportunity for sleep or irregular sleep schedule, a sleep disorder like obstructive sleep apnea and side effects from certain medications (sedating medications). Other potential causes of excessive daytime sleepiness include certain medical and psychiatric conditions and sleep disorders, such as narcolepsy. Obstructive sleep apnea is a particularly significant cause of excessive daytime sleepiness. An estimated 26 to 32 percent of adults are at risk of or have obstructive sleep apnea, and the prevalence is expected to increase. The evaluation and management of excessive daytime sleepiness is based on the identification and treatment of underlying conditions (particularly obstructive sleep apnea), and the appropriate use of activating medications.

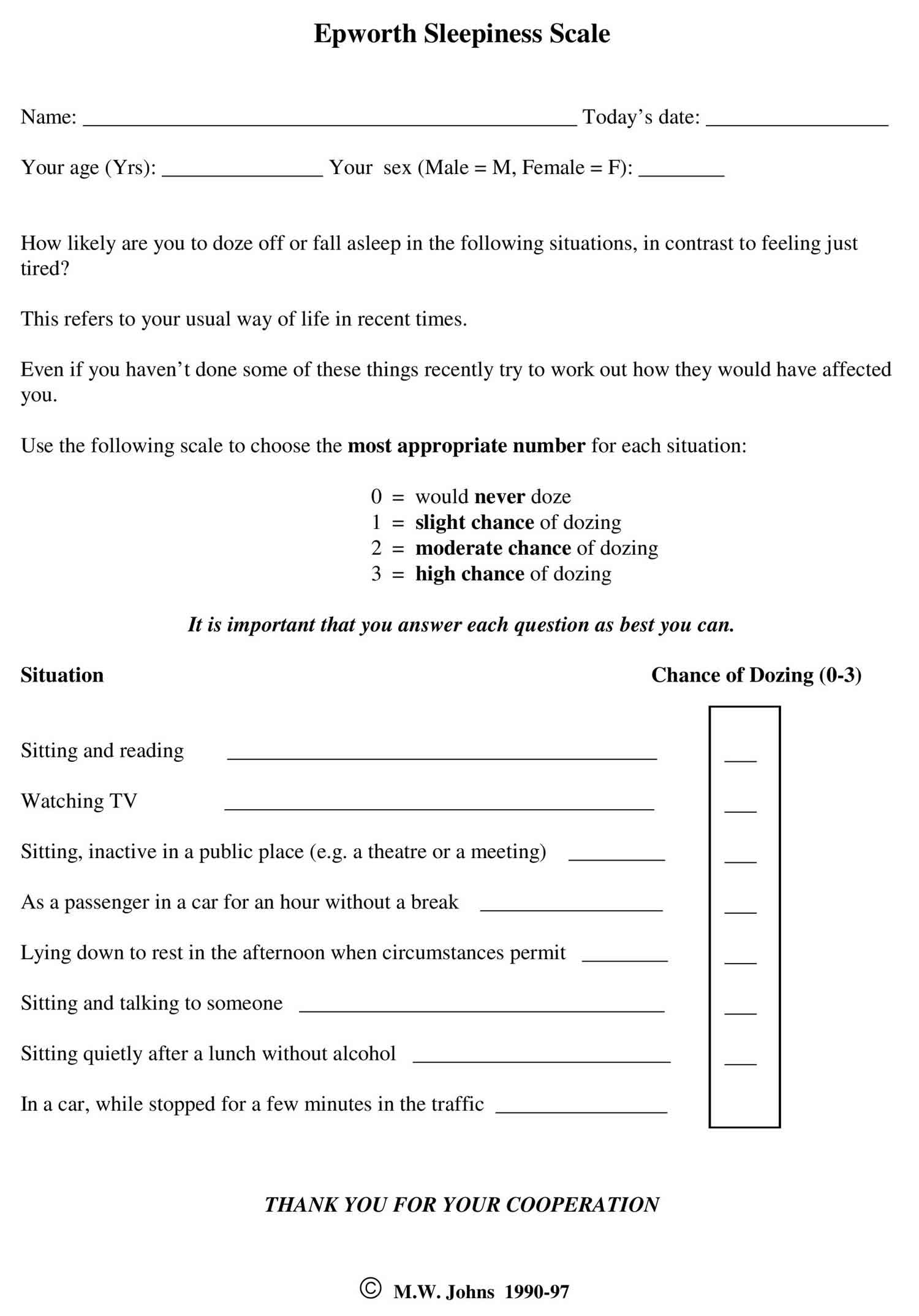

There are several questionnaires available to assess excessive daytime sleepiness. One of the most popular questionnaires is the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (see Figure 1 below). This scale uses eight questions composed of eight scenarios. The user rates the likelihood of falling asleep from 0 -3 points per scenario. The total is tallied up to a highest sleepiness score of 24. Once you and your doctor have determined the cause of excessive sleepiness, you can create a treatment plan together. For most people, that involves changing sleep habits and improving behaviors and elements of the sleep environment. For others, further medical tests or sleep studies may be indicated.

If you are frequently tired, work less productively, make mistakes, have lapses in judgment or wakefulness, or feel unable to enjoy or fully participate in life’s activities, don’t just “push through.” If you’ve been excessively tired for a long time, it may feel normal to you, but poor sleep and resulting excessive sleepiness can have drastic, long-term effects on your health (for example reduced sleep is tied to cardiovascular problems and weight gain), as well as how you think and feel. Not only that, when you go about your day overtired, you put yourself and others at risk, since motor vehicle accidents and other dangerous errors are often caused by sleepiness. If you’re feeling the symptom of excessive sleepiness, talk to your doctor so the two of you can take a closer look at your sleep habits and take steps to improve your health, and ultimately get you on the road to sleeping and feeling better.

Epworth sleepiness scale

Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) is a scale intended to measure ‘daytime sleepiness’ that is measured by use of a very short questionnaire. This can be helpful in diagnosing sleep disorders. Epworth Sleepiness Scale was introduced in 1991 by Dr Murray Johns of Epworth Hospital in Melbourne, Australia and subsequently modified it slightly in 1997.

Epworth Sleepiness Scale is a self-administered questionnaire with 8 questions. The questionnaire asks the subject to rate his or her probability of falling asleep on a scale of increasing probability from 0 to 3 (0 = no chance of dozing 1 = slight chance of dozing 2 = moderate chance of dozing 3 = high chance of dozing) for eight different situations that most people engage in during their daily lives, though not necessarily every day. The scores for the eight questions are added together to obtain a single number. A number in the 0–9 range is considered to be normal while a number in the 10–24 range indicates that expert medical advice should be sought. For instance, scores of 11-15 are shown to indicate the possibility of mild to moderate sleep apnea, where a score of 16 and above indicates the possibility of severe sleep apnea or narcolepsy. Certain questions in the scale were shown to be better predictors of specific sleep disorders, though further tests may be required to provide an accurate diagnosis.

Figure 1. Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS)

Epworth Sleepiness Scale score

Epworth Sleepiness Scale is a scale intended to measure daytime sleepiness that is measured by use of a very short questionnaire. Epworth Sleepiness Scale can be helpful in diagnosing sleep disorders.

Sitting and reading

- 0 – no chance of dozing

- 1 – slight chance of dozing

- 2 – moderate chance of dozing

- 3 – high chance of dozing

Watching television

- 0 – no chance of dozing

- 1 – slight chance of dozing

- 2 – moderate chance of dozing

- 3 – high chance of dozing

Sitting, inactive in a public place (e.g. a theater or meeting)

- 0 – no chance of dozing

- 1 – slight chance of dozing

- 2 – moderate chance of dozing

- 3 – high chance of dozing

As a passenger in a car for an hour without a break

- 0 – no chance of dozing

- 1 – slight chance of dozing

- 2 – moderate chance of dozing

- 3 – high chance of dozing

Lying down to rest in the afternoon when circumstances permit

- 0 – no chance of dozing

- 1 – slight chance of dozing

- 2 – moderate chance of dozing

- 3 – high chance of dozing

Sitting and talking to someone

- 0 – no chance of dozing

- 1 – slight chance of dozing

- 2 – moderate chance of dozing

- 3 – high chance of dozing

Sitting quietly after a lunch without alcohol

- 0 – no chance of dozing

- 1 – slight chance of dozing

- 2 – moderate chance of dozing

- 3 – high chance of dozing

In a car, while stopped for a few minutes in the traffic

- 0 – no chance of dozing

- 1 – slight chance of dozing

- 2 – moderate chance of dozing

- 3 – high chance of dozing

Add up all the scores and write in the designated “total score box”.

Interpret the results as per the scale below.

- Score: 1- 6 = Enough Sleep

- Score: 7-8 = Tend to be sleepy during the day

- Score: 9- 15 = Very sleepy

- Score: 16+ = Dangerously sleepy

Your Score is less than 9 and in considered normal

Your Score is above 9 and its recommended that you should seek medical advice.

Epworth Sleepiness Scale interpretation

Epworth Sleepiness Scale is a self-administered questionnaire with 8 questions. Respondents are asked to rate, on a 0-3 scale (0 = no chance of dozing 1 = slight chance of dozing 2 = moderate chance of dozing 3 = high chance of dozing), their usual chances of dozing off or falling asleep while engaged in eight different activities. Most people engage in those activities at least occasionally, although not necessarily every day. The Epworth Sleepiness Scale score (the sum of 8 item scores, 0-3) can range from 0 to 24. The higher the Epworth Sleepiness Scale score, the higher that person’s average sleep propensity in daily life, or their ‘daytime sleepiness’. A number in the 0–9 range is considered to be normal while a number in the 10–24 range indicates that expert medical advice should be sought. For instance, scores of 11-15 are shown to indicate the possibility of mild to moderate sleep apnea, where a score of 16 and above indicates the possibility of severe sleep apnea or narcolepsy. Certain questions in the Epworth Sleepiness Scale were shown to be better predictors of specific sleep disorders, though further tests may be required to provide an accurate diagnosis.

Excessive daytime sleepiness causes

Excessive daytime sleepiness can occur secondary to sleep deprivation, medication effects, illicit substance use, obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), and other medical and psychiatric conditions 12. Excessive sleepiness caused by a primary hypersomnia of central origin (e.g., narcolepsy, idiopathic hypersomnia) is less common.

Common causes of excessive daytime sleepiness:

- Primary hypersomnias of central origin

- Narcolepsy (0.02 to 0.18 percent of population)

- Idiopathic hypersomnia (10 percent of patients with suspected narcolepsy)

- Other rare primary hypersomnias (example: Kleine-Levin syndrome)

- Secondary hypersomnias

- Sleep disorders

- Sleep-related breathing disorders

- Excessive daytime sleepiness secondary to obstructive sleep apnea (general population prevalence is 2 percent of women and 4 percent of men)

- Behavioral sleep deprivation

- Especially common in adolescents and shift workers

- Other sleep disorders: Includes circadian rhythm sleep disorders, sleep-related movement disorders

- Sleep disorders

- Medical or psychiatric conditions

- Medication effects: Includes prescription, nonprescription, and drugs of abuse

- Psychiatric conditions: Especially depression

- Medical conditions: Includes head trauma, stroke, cancer, inflammatory conditions, encephalitis, neurodegenerative conditions

Hypersomnia due to secondary causes is much more common than primary hypersomnia 12.

Sleep deprivation

Sleep deprivation is probably the most common cause of excessive daytime sleepiness. Symptoms can occur in healthy persons after even mild sleep restriction. Studies that restricted healthy adults to six hours of sleep per night for 14 successive nights showed a cumulative significant impairment of neurobiological functions 13. Symptoms of sleep deprivation can occur after only one night of sleep loss 13 and persons who are chronically sleep deprived are often unaware of their increasing cognitive and performance deficits 6. Paradoxically, most types of chronic insomnia (including primary insomnia, psychopathological insomnia, and paradoxical insomnia) are associated with daytime hyperarousal rather than excessive daytime sleepiness. The presence of excessive daytime sleepiness in a patient with insomnia suggests a comorbidity such as a sleep-related breathing disorder or a mood disorder 14.

Medication and drug side effects

Sleepiness is the most commonly reported side effect of pharmacologic agents that act on the central nervous system. The modulation of sleep and wakefulness is a complex process involving multiple factors and systems. Although no single chemical neurotransmitter has been identified as necessary or sufficient in the control of sleep, most drugs with clinical sedative or hypnotic actions affect one or more of the central neurotransmitters implicated in the neuromodulation of sleep and wakefulness, including dopamine, epinephrine, norepinephrine, acetylcholine, serotonin, histamine, glutamate, γ-aminobutyric acid, and adenosine 15.

Ethanol is the most widely used agent with sedative effects 16. Nonprescription sleeping pills and other medications containing sedating H1 antihistamines, such as diphenhydramine (Benadryl), hydroxyzine (Atarax, brand no longer available in the United States), or triprolidine (Zymine) are also commonly used. Sedating antihistamines, longer-acting benzodiazepines, and sedating antidepressants are associated with decreased performance on driving tests and increased rates of next-day motor vehicle incidents attributed to daytime sleepiness 14. Of the antihypertensive medications in widespread use, tiredness, fatigue, and daytime sleepiness are side effects commonly associated with beta blockers such as propranolol (Inderal), but sedation is also the most common side effect reported for the alpha2-agonists clonidine (Catapres) and methyldopa (Aldomet, brand no longer available in the United States). Sedation is also commonly reported by patients taking anticonvulsant or antipsychotic medications. Among drugs of abuse, marijuana has significant sedating effects. Adolescents abusing stimulants such as amphetamines and cocaine may experience persistent daytime sedation after long episodes of drug-induced wakefulness.

Medication classes commonly associated with daytime sleepiness 15:

- Alpha-adrenergic blocking agents

- Anticonvulsants (e.g., hydantoins, succinimides)

- Antidepressants (monoamine oxidase inhibitors, tricyclics, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors)

- Antidiarrhea agents

- Antiemetics

- Antihistamines

- Antimuscarinics and antispasmodics

- Antiparkinsonian agents

- Antipsychotics

- Antitussives

- Barbiturates

- Benzodiazepines, other gamma-aminobutyric acid affecting agents, and other anxiolytics

- Beta-adrenergic blocking agents

- Genitourinary smooth muscle relaxants

- Opiate agonists and partial opiate agonists

- Skeletal muscle relaxants

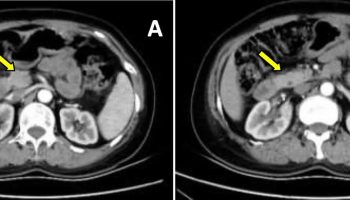

Obstructive sleep apnea

Excessive daytime sleepiness is the most common symptom of obstructive sleep apnea. A sleep disorder caused by blockage of the upper airway, obstructive sleep apnea results in episodes of cessation of breathing (apneas) or a reduction in airflow (hypopneas), and is defined as greater than or equal to five apneic or hypopneic episodes per hour of sleep. These events induce recurrent hypoxia and repetitive arousals from sleep. For adults 30 to 60 years of age, the prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea has been estimated to be 9 percent for women and 24 percent for men. In patients with obstructive sleep apnea, approximately 23 percent of women and 16 percent of men experience excessive daytime sleepiness 17. Sleep-related breathing disorders may be significantly under-recognized as causes of excessive daytime sleepiness. One study estimated that 93 percent of women and 82 percent of men with moderate to severe obstructive sleep apnea are undiagnosed 18. Furthermore, 26 to 32 percent of U.S. adults are at risk of developing or currently have obstructive sleep apnea. Because increasing age and obesity are significant risk factors for obstructive sleep apnea, the prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea is set to increase rapidly. By 2025, obesity will affect 18% of men and over 21% of women worldwide, and that severe obesity will affect 6% of all men and 9% of all women around the world. In some nations, obesity is already present in more than one-third of the adult population and contributes significantly to overall poor health and high annual medical costs 19.

Persons with obstructive sleep apnea have an increased risk of motor vehicle incidents because of their impaired vigilance 18. In 2000, more than 800,000 drivers in the United States were involved in obstructive sleep apnea-related motor vehicle collisions, resulting in 1,400 deaths 20. Approximately 25 percent of persons with untreated obstructive sleep apnea report frequently falling asleep while driving 21. Because of associated daytime sleepiness, reduced vigilance, and inattention, persons with obstructive sleep apnea may have work performance difficulties and are at a high risk of being involved in occupational incidents 22.

Other secondary hypersomnias

Many medical conditions can cause secondary excessive daytime sleepiness, including head trauma, stroke, tumors, inflammatory conditions, encephalitis, and genetic and neurodegenerative diseases. Psychiatric conditions, especially depression, can also result in excessive daytime sleepiness. Sleep disorders such as circadian rhythm disorders (e.g., jet lag, shift work disorder), periodic limb movement disorder, and restless legs syndrome can also contribute to significant levels of daytime sleepiness in some persons.

Primary hypersomnias

Narcolepsy, the most common of the primary hypersomnias, is reported to affect 0.02 to 0.18 percent of the adult population, but may be significantly underdiagnosed. Approximately 25 to 30 percent of patients with narcolepsy have associated cataplexy (i.e., sudden and transient loss of muscle tone associated with emotions) 23. Less common are the other primary hypersomnias of central origin, including idiopathic hypersomnia, menstrual hypersomnia, and Kleine-Levin syndrome (a rare form of recurrent hypersomnia most common in male adolescents) 12.

Excessive daytime sleepiness symptoms

Excessive sleepiness or excessive daytime sleepiness is defined by having an increased pressure to fall asleep during typical wake hours 1. People who have excessive sleepiness feel drowsy and sluggish most days, and these symptoms often interfere with their work, school, activities, or relationships. Although patients with excessive daytime sleepiness often complain of “fatigue,” excessive sleepiness is different from fatigue which is characterized by low energy and the need to rest (not necessarily sleep). Excessive sleepiness is also different from depression, in which a person may have a reduced desire to do normal activities, even the ones they used to enjoy. Persons with excessive daytime sleepiness are at risk of motor vehicle and work-related incidents, and have poorer health than comparable adults 9. The prevalence of excessive daytime sleepiness is highest in adolescents, older persons, and shift workers 10, but assessment of its true prevalence is difficult because of the subjective nature of the symptoms, inconsistencies in terminology, and a lack of consensus on methods of diagnosis and assessment. Some persons use subjective terminology (e.g., drowsiness, languor, inertness, fatigue, sluggishness) when describing symptoms of excessive daytime sleepiness 11.

Excessive daytime sleepiness diagnosis

To diagnose your excessive daytime sleepiness, your doctor may make an evaluation based on your signs and symptoms, an examination, and tests. Your doctor may refer you to a sleep specialist in a sleep center for further evaluation. Your doctor also may refer you to an ear, nose and throat doctor to rule out any anatomic blockage in your nose or throat.

You’ll have a physical examination, and your doctor will examine the back of your throat, mouth and nose for extra tissue or abnormalities. Your doctor may measure your neck and waist circumference and check your blood pressure.

A sleep specialist may conduct additional evaluations to diagnose your condition, determine the severity of your condition and plan your treatment. The evaluation may involve overnight monitoring of your breathing and other body functions as you sleep.

There are several tests that can be done to diagnose sleepiness, which will determine whether the individual has primary (originating in the brain) or secondary (originating as a result of another disease) sleepiness. First, the physician will look for other obvious sleep disorders that could be causing the excessive sleepiness, with the primary goal being to determine if there are treatable medical conditions present. These tests could include polysomnography, subjective scales such as the Epworth Sleepiness Scale and the Stanford Sleepiness Scale, as well as objective tests like the multiple sleep latency test. The physician will usually make the diagnosis when symptoms have been present for three consecutive months and there are no other underlying diseases.

Tests to detect dyssomnias include:

- Polysomnography. During this sleep study, you’re hooked up to equipment that monitors your heart, lung and brain activity, breathing patterns, arm and leg movements, and blood oxygen levels while you sleep. You may have a full-night study, in which you’re monitored all night, or a split-night sleep study. In a split-night sleep study, you’ll be monitored during the first half of the night. If you’re diagnosed with obstructive sleep apnea, staff may wake you and give you continuous positive airway pressure for the second half of the night. Polysomnography can help your doctor diagnose obstructive sleep apnea and adjust positive airway pressure therapy, if appropriate. This sleep study can also help rule out other sleep disorders that can cause excessive daytime sleepiness but require different treatments, such as leg movements during sleep (periodic limb movements) or sudden bouts of sleep during the day (narcolepsy).

- The Multiple Sleep Latency Test (MSLT) and Maintenance of Wakefulness Test (MWT) are tests that are performed in a sleep center. The patient is instructed to try to fall asleep (MSLT) or try to stay awake (MWT). These tests are usually performed during the daytime after a nighttime sleep study. They usually consist of 4 or 5 nap time tests.

- Home sleep apnea testing. Under certain circumstances, your doctor may provide you with an at-home version of polysomnography to diagnose obstructive sleep apnea. This test usually involves measurement of airflow, breathing patterns and blood oxygen levels, and possibly limb movements and snoring intensity.

Changes in Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Regulations for Obstructive Sleep Apnea Home Sleep Testing and CPAP (continuous positive airway pressure) Treatment 24

- Obstructive sleep apnea diagnosis is based on an apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) > 15 or an AHI > 5 to 15 associated with daytime sleepiness, impaired cognition, mood disorders, or insomnia, or documented hypertension, ischemic heart disease, or history of smoking

- Apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) is based on standard polysomnography or home sleep testing

- Home sleep testing must only be performed by a physician with board certification in sleep medicine or a physician who is an active staff member of a sleep laboratory or clinic accredited by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine or the Joint Commission

- CPAP is initially limited to a 12-week period, with coverage extended for persons whose symptoms improve based on follow-up physician re-evaluation and with objective evidence of CPAP utilization.

Figure 2. Excessive daytime sleepiness diagnostic algorithm

Footnote: Algorithm for the diagnosis and treatment of conditions that cause excessive daytime sleepiness.

Abbreviations: CPAP = continuous positive airway pressure; OSA = obstructive sleep apnea

Quantifying excessive daytime sleepiness

Subjective assessment of symptoms using questionnaires and clinical assessment of behavioral impact may not accurately reflect the degree of physiologic sleepiness 25. The effects of sleepiness on daytime performance can be assessed by tests of complex reaction time and coordination, or by tests that assess complex behavioral tasks likely to be affected by sleepiness (e.g., driving performance) 26. Performance measures are susceptible to influences that are not task related (e.g., motivation, distraction, comprehension of instructions); therefore, the results of performance tests and questionnaires do not always correlate 11.

The most common tests for assessing psychological variations in daytime sleepiness are the Multiple Sleep Latency Test (MSLT) and the Maintenance of Wakefulness Test (MWT). Both of these tests use modified polysomnography to assess sleep onset latency (i.e., the amount of time it takes to fall asleep) during a series of waking nap periods. Overnight polysomnography is required before the MSLT or MWT to assess the disordered sleep pattern and test for significant obstructive sleep apnea. To diagnose narcolepsy without cataplexy, the Multiple Sleep Latency Test (MSLT) must demonstrate hypersomnolence and early onset of rapid eye movement sleep. The Maintenance of Wakefulness Test (MWT) can be used to assess improvements in waking performance after treatment in persons with excessive daytime sleepiness who could potentially be dangerous to self and others, such as commercial drivers and airplane pilots 27.

Excessive daytime sleepiness treatment

Excessive daytime sleepiness treatment will depend greatly on the underlying cause of sleepiness and whether it is a primary or secondary sleep disorder. Sometimes treatment of excessive daytime sleepiness can be as simple as discontinuing or modifying the use of medication (all prescription and nonprescription medications) and drugs of abuse. Other times, catching up on sleep will alleviate the excessive sleepiness; however, more often than not, it is more appropriate to treat the underlying cause than it is to treat the symptom. Most common treatments include the use of stimulant medications like amphetamines to help the individual stay awake throughout the day. In addition, behavioral therapy, sleep hygiene, and education are usually added to a treatment regimen.

In obstructive sleep apnea—the most dangerous and physiologically disruptive cause of excessive daytime sleepiness—treatment with positive pressure devices (e.g., CPAP) during sleep improves symptoms of daytime sleepiness for most patients 28. The effects of other treatments for obstructive sleep apnea (e.g., medications, dental appliances, surgery) on daytime sleepiness have not been well documented 29.

Modafinil (Provigil) is considered to be the first-line activating agent for the treatment of excessive daytime sleepiness. It is indicated for the treatment of persistent sleepiness associated with obstructive sleep apnea in patients already being treated with CPAP, and for the treatment of daytime sleepiness in patients with shift work disorder 30. Modafinil is pharmacologically distinct from and has a much lower potential for abuse (Schedule IV) than the amphetamines, and has a generally benign side-effect profile. Other medications that must be used with caution to induce alertness in somnolent patients include the amphetamines (dextroamphetamine [Dexedrine], methylphenidate [Ritalin]) and pemoline (Cylert, not available in the United States). The amphetamines are Schedule II prescription drugs and are considered to have a high potential for abuse. Side effects of amphetamines include personality changes, tremor, hypertension, headaches, and gastroesophageal reflux 31. Pemoline can cause hepatic toxicity in susceptible patients. The use of activating agents is inappropriate in hypersomnolent patients with untreated obstructive sleep apnea—although daytime sleepiness may be improved with these agents, the patient remains at risk from the pathophysiologic consequences of untreated obstructive sleep apnea.

Medical and legal considerations

Legal requirements for reporting excessive daytime sleepiness that may impair driving vary from state to state 32. The physician treating patients with excessive daytime sleepiness (or patients using drugs likely to affect driving performance) has the responsibility to make a clinical assessment of the patient’s overall risk of unsafe driving, and to document driving recommendations and precautions. A physician should report patients who fail to comply with treatment, particularly high-risk persons such as airline pilots, truck, bus, and occupational drivers, and those with a history of recent sleepiness-associated incidents.

References- https://www.sleepassociation.org/sleep-disorders/more-sleep-disorders/excessive-daytime-sleepiness/

- National Sleep Foundation. State of the states report on drowsy driving. November 2007.

- NTSB. Factors that affect fatigue in heavy truck accidents safety study. Washington, DC: National Transportation Safety Board; 1995.

- Masa JF, Rubio M, Findley LJ. Habitually sleepy drivers have a high frequency of automobile crashes associated with respiratory disorders during sleep. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162(4 pt 1):1407–1412.

- Pagel JF, Forister N, Kwiatkowki C. Adolescent sleep disturbance and school performance: the confounding variable of socioeconomics. J Clin Sleep Med. 2007;3(1):19–23.

- Sforza E, de Saint Hilaire Z, Pelissolo A, Rochat T, Ibanez V. Personality, anxiety and mood traits in patients with sleep-related breathing disorders: effect of reduced daytime alertness. Sleep Med. 2002;3(2):139–145.

- Chen I, Vorona R, Chiu R, Ware JC. A survey of subjective sleepiness and consequences in attending physicians. Behav Sleep Med. 2008;6(1):1–15.

- Johnson EO. Sleep in America: 2000. Results from the National Sleep Foundation’s 2000 Omnibus sleep poll. Washington, DC: The National Sleep Foundation; 2000.

- Excessive Daytime Sleepiness. Am Fam Physician. 2009 Mar 1;79(5):391-396. https://www.aafp.org/afp/2009/0301/p391.html

- Friedman NS. Determinants and measurements of daytime sleepiness. In: Pagel JF, Pandi-Perumal SR, eds. Primary Care Sleep Medicine: A Practical Guide. Totowa, N.J.: Humana Press; 2007:61–82.

- Buysse DJ. Drugs affecting sleep, sleepiness, and performance. In: Monk TH, ed. Sleep, Sleepiness, and Performance. Chichester: Wiley; 1991:4–31.

- American Academy of Sleep Medicine. The International Classification of Sleep Disorders: Diagnostic & Coding Manual. 2nd ed. Westchester, Ill.: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2005.

- Van Dongen H, Maislin G, Mullington JM, Dinges DF. The cumulative cost of additional wakefulness: dose-response effects on neurobehavioral functions and sleep physiology from chronic sleep restriction and total sleep deprivation [published correction appears in Sleep. 2004; 27(4):600]. Sleep. 2003;26(2):117–126.

- Pagel JF. Sleep disorders in primary care: evidence-based clinical practice. In: Pagel JF, Pandi-Perumal SR, eds. Primary Care Sleep Medicine: A Practical Guide. Totowa, N.J.: Humana Press; 2007:1–14.

- Pagel JF. Medications that induce sleepiness. In: Lee-Chiong TL, ed. Sleep: A Comprehensive Handbook. Hoboken, N.J.: Wiley-Liss; 2006:175–182.

- Sateia MJ, Doghramji K, Hauri PJ, Morin CM. Evaluation of chronic insomnia. An Amerrican Academy of Sleep Medicine review. Sleep. 2000;23(2):243–308.

- Young T, Evans L, Finn L, Palta M. Estimation of the clinically diagnosed proportion of sleep apnea syndrome in middle-aged men and women. Sleep. 1997;20(9):705–706.

- Young T, Peppard PE, Gottlieb DJ. Epidemiology of obstructive sleep apnea: a population health perspective. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165(9):1217–1239.

- World Kidney Day 10 March 2017. https://www.who.int/life-course/news/events/world-kidney-day-2017/en/

- Sassani A, Findley LJ, Kryger M, Goldlust E, George C, Davidson TM. Reducing motor-vehicle collisions, costs, and fatalities by treating obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Sleep. 2004;27(3):453–458.

- Findley LJ, Levinson MP, Bonnie RJ. Driving performance and automobile accidents in patients with sleep apnea. Clin Chest Med. 1992;13(3):427–435.

- Lindberg E, Carter N, Gislason T, Janson C. Role of snoring and daytime sleepiness in occupational accidents. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164(11):2031–2035.

- Thorpy MJ. Cataplexy associated with narcolepsy: epidemiology, pathophysiology and management. CNS Drugs. 2006;20(1):43–50.

- https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Coverage/Coverage-with-Evidence-Development/CPAP

- Roehrs T, Carskadon MA, Dement WC, Roth T. Daytime sleepiness and alertness. In: Kryger MH, Roth T, Dement WC, eds. Principles and Practice of Sleep Medicine. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, Pa.: Saunders; 2000:43–52.

- George CF. Vigilance impairment: assessment by driving simulators. Sleep. 2000;23(suppl 4):S115–S118.

- Kreiger J. Clinical approach to excessive daytime sleepiness. Sleep. 2000;23(suppl 4):S95–S98.

- Findley L, Smith C, Hooper J, Dineen M, Suratt PM. Treatment with nasal CPAP decreases automobile accidents in patients with sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161(3 pt 1):857–859.

- Veasey SC, Guilleminault C, Strohl KP, Sanders MH, Ballard RD, Magalang UJ. Medical therapy for obstructive sleep apnea: a review by the Medical Therapy for Obstructive Sleep Apnea Task Force of the Standards of Practice Committee of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. Sleep. 2006;29(8):1036–1044.

- Czeisler CA, Walsh JK, Roth T, et al. Modafinil for excessive sleepiness associated with shift-work sleep disorder [published correction appears in N Engl J Med. 2005;353(10):1078]. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(5):476–486.

- Wilens TE, Biederman J. The stimulants. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1992;15(1):191–222.

- Boehlecke BA. Medicolegal aspects of obstructive sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome. In: Pagel JF, Pandi-Perumal SR, eds. Primary Care Sleep Medicine: A Practical Guide. Totowa, N.J.: Humana Press; 2007:155–160.