Fascioliasis

Fascioliasis is a parasitic infection caused by Fasciola parasites, which are flat worms referred to as liver flukes 1. Two Fasciola species (types) infect people. The main species is Fasciola hepatica, which is also known as “the common liver fluke” or “the sheep liver fluke.” A related species, Fasciola gigantica, also can infect people. The adult (mature) flukes are found in the bile ducts (the duct system of the liver) of infected people and animals, such as sheep and cattle. In general, fascioliasis is more common in livestock and other animals than in people. Even so, the number of infected people in the world is thought to exceed two million 2.

Adult Fasciola hepatica flukes grow to become spiny-appearing, brown leaf-shaped, flatworms, typically around 30 mm by 15 mm in size and easily seen with the naked eye. Anteriorly, they have 2 suckers, a large one on the ventral side referred to as the acetabulum that allows the fluke to suction itself to the wall of the bile duct and remain in place so the smaller more anterior sucker may feed on the bile 3. As their name implies, Fasciola gigantica flatworms can grow up to 75 mm in length but are otherwise similar in appearance to their smaller counterparts 4.

Fascioliasis is found in more than 70 countries except Antarctica, especially where there are sheep or cattle. Fasciola gigantica has been found in some tropical areas, in parts of Africa and Asia, and also in Hawaii. Except for parts of Western Europe, human fascioliasis has mainly been documented in developing countries. For example, the areas with the highest known rates of human fascioliasis are in the Andean highlands of Bolivia and Peru. People usually become infected by eating raw watercress or other water plants contaminated with immature Fasciola parasite larvae. The young worms move through the intestinal wall, the abdominal cavity, and the liver tissue, into the bile ducts, where they develop into mature adult flukes that produce eggs. The pathology typically is most pronounced in the bile ducts and liver. Fasciola infection is both treatable and preventable.

The global prevalence of fascioliasis is estimated between 2.4 and 17 million and is typically under-reported and under-diagnosed. In the United States, sporadic cases are seen mainly in travelers and immigrants. Disease in cattle and livestock is more prevalent in the United States and varies in geographical location 5. Fasciola hepatica is endemic to Europe and Asia, occasionally seen in Northern Africa, Central and South America, and the Middle East, and sporadic cases rarely pop in the United States and the Caribbean 6. Fasciola gigantica infects domestic livestock across Asia, the Pacific Islands, and some parts of Northern Africa 4. In parts of Africa and Asia, the 2 species overlap, and their clinical presentations are indistinguishable. Cattle and sheep are the most common definitive hosts, but the flatworms often infect several other grazing animals in the wild. Humans who live in regions where cattle and sheep industries are prominent and who consume raw aquatic vegetation, watercress in particular, are at the highest risk of contracting the parasite 1.

There are 2 distinct phases of the fascioliasis infection:

The acute (hepatic) phase usually begins 6 to 12 weeks after ingestion of metacercariae from a contaminated water source. The first sign is usually very high fever, followed by right upper quadrant pain, hepatomegaly, and occasionally jaundice. Cell blood count (CBC) differential will show a marked peripheral eosinophilia. Patients often present with associated myalgias, urticarial rash, nausea, anorexia, and diarrhea. These symptoms are attributed to the Fasciola flatworms migrating through the liver parenchyma and setting off the inflammatory and immune responses along the way. Additional laboratory diagnostic clues include transaminitis, anemia, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and hypergammaglobulinemia. Early complications are rare but may be seen with high parasite load and include ascites, hemobilia, subcapsular hematomas, and rarely severe parenchymal liver necrosis. However, in most cases, acute symptoms generally resolve within 6 weeks, and the infection settles into the chronic phase 1.

Early extrahepatic manifestations are typically type III (immune complex deposition) or type IV (IgE) hypersensitivity-mediated. A reactive eosinophilic pneumonitis is nonspecific for helminth infections and is well described in literature 7. Overwhelming activation of the host’s immune system and inflammatory response can cause vasculitis. In the heart can lead to myocarditis which in turn can cause cardiac conduction abnormalities. In the brain cerebral vasculitis may lead to focal neurologic deficits or seizures but these are all highly uncommon. Generalized lymphadenopathy is often present 1.

The chronic (biliary) phase usually begins about 6 months after acute infection once the flukes have settled into the bile ducts and may last up to a decade or more. Usually asymptomatic, but occasionally can present as chronic epigastric and right upper quadrant pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, hepatomegaly, jaundice, and failure to thrive. Peripheral eosinophilia will not likely be present. Chronic common bile duct obstructions may develop and lead to recurrent jaundice, cholelithiasis, pancreatitis, and more seriously, ascending cholangitis. Prolonged infection and/or high parasite load leads to chronic hepatobiliary damage and can result in chronic biliary cirrhosis, sclerosing cholangitis, and even cholangiocarcinoma 8.

Fasciola’s migration out of the intestine and up into the liver is not always perfect; sometimes they get lost. Ectopic fascioliasis is the term given to the infection occurring outside the hepatobiliary system. They may end up almost anywhere in the body. Their presence results in localized mononuclear, eosinophilic infiltration that causes secondary tissue damage from the host’s immune response. Frequently, when they get lost, they end up in the subcutaneous tissue of the abdominal wall, but they may also end up in the peritoneum, intestinal wall, lungs, heart, brain, muscles, or eyes. Traveling flatworms under the skin or fat tissue leave behind migrating, pruritic, erythematous, painful nodules 1 to 6 cm in diameter and may be seen or palpated. Occasionally nodules can become infected and turn into a local abscess 9. Another rare form of ectopic fascioliasis is Halzoun syndrome or pharyngeal fascioliasis. It is sometimes seen in the Middle East in areas where people eat raw liver. In this case, the metacercariae or young adult flukes living in the ingested liver attach themselves to the mucosa of the upper respiratory or digestive tract causing pharyngitis or esophagitis. Rarely edema and swelling of the upper airway can be so severe that patients have asphyxiated 10.

Fascioliasis is a treatable disease. Triclabendazole is the drug of choice. It is given by mouth, usually in two doses. Most people respond well to the treatment.

Can Fasciola be spread directly from one person or animal to another?

No. Fasciola cannot be passed directly from one person to another. The eggs passed in the stool of infected people (and animals) need to develop (mature) in certain types of freshwater snails, under favorable environmental conditions, to be able to infect someone else.

Under unusual circumstances, people might get infected by eating raw or undercooked sheep or goat liver that contains immature forms of the parasite.

Can people get infected with Fasciola in the United States?

Yes. It is possible, but few cases have been reported in published articles. Some cases have been documented in Hawaii, California, and Florida.

However, most reported cases in the United States have been in people, such as immigrants, who were infected in countries where fascioliasis is well known to occur.

Can fascioliasis be treated?

Yes. Fascioliasis is a treatable disease. Triclabendazole is the drug of choice. It is given by mouth, usually in two doses. Most people respond well to the treatment.

Fascioliasis cause

People get infected by accidentally ingesting (swallowing) the Fasciola parasite. The main way this happens is by eating raw watercress or other contaminated freshwater plants. Another way people might get infected is by ingesting contaminated water, such as by drinking it or by eating vegetables that were washed or irrigated with contaminated water.

Infective Fasciola larvae (metacercariae) are found in contaminated water, typically stuck to (encysted on) water plants or potentially floating in the water—such as in marshy areas, ponds, or flooded pastures. The main way people (and animals) become infected is by eating raw watercress or other contaminated water plants (for example, if the plants are eaten as a snack or in salads or sandwiches). Some data suggest people also might get infected by ingesting contaminated water, such as by drinking it or by eating vegetables that were washed or irrigated with contaminated water. Under unusual circumstances, infection might result from eating raw or undercooked sheep or goat liver that contains immature forms of the parasite.

The possibility of becoming infected in the United States should be considered, despite the fact that few locally acquired cases have been documented. The prerequisites for the Fasciola life cycle exist in some parts of the United States. In addition, transmission because of imported contaminated produce could occur, as has been documented in Europe.

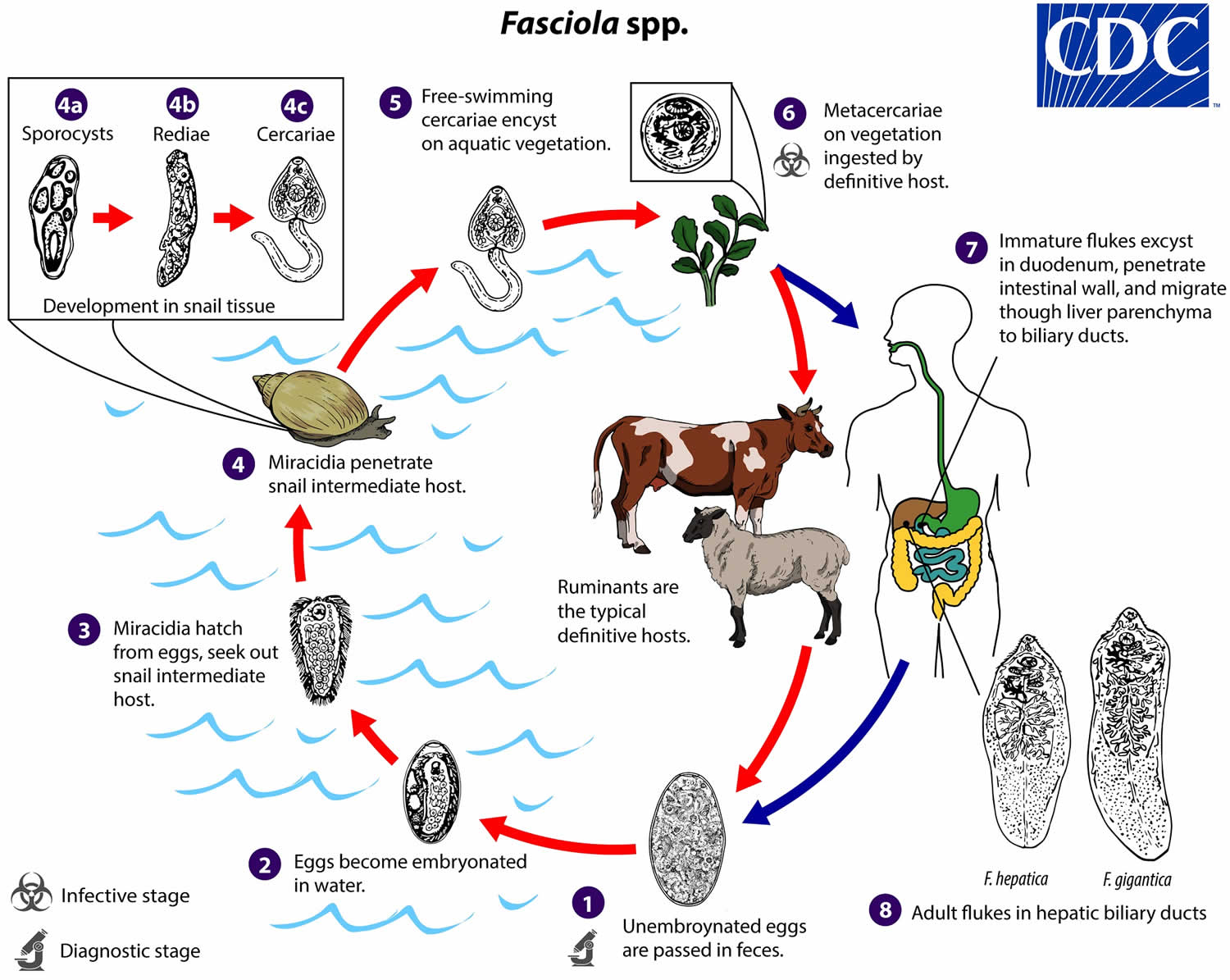

Fasciola life cycle

The trematodes Fasciola hepatica also known as the common liver fluke or the sheep liver fluke and Fasciola gigantica are large liver flukes (Fasciola hepatica: up to 30 mm by 15 mm; Fasciola gigantica: up to 75 mm by 15 mm) easily seen with the naked eye, which are primarily found in domestic and wild ruminants (their main definitive hosts) but also are causal agents of fascioliasis in humans.

Although Fasciola hepatica and Fasciola gigantica are distinct species, “intermediate forms” that are thought to represent hybrids of the two species have been found in parts of Asia and Africa where both species are endemic. These forms usually have intermediate morphologic characteristics (e.g. overall size, proportions), possess genetic elements from both species, exhibit unusual ploidy levels (often triploid), and do not produce sperm. Further research into the nature and origin of these forms is ongoing.

Regardless of whether the host is bovine or human, the life cycle remains the same. Adult liver flukes release un-embryonated eggs into their host’s bile ducts which then pass into their stools. The host defecates in the environment near or within a pond or steam. Eggs become embryonated when they reach a water source and hatch into free-swimming miracidia that seek out an intermediate host, one of several species of amphibious snail. The miracidium will bore itself directly into the tissues of the snail. Once inside, miracidia go through several metamorphoses first becoming sporocysts that give rise to mother rediae which in turn produce daughter rediae. Germ balls develop inside the daughter rediae that become cercariae which will grow and bore back out of the snail to again become free-swimming in the environment. They go on to encyst as metacercariae on aquatic vegetation and are eaten by their definitive host 11.

The flatworms most commonly cause infection when humans when they eat vegetation contaminated with metacercariae, for example, watercress. Metacercariae excyst in the duodenum, and similarly in the snail, and penetrate through the intestinal wall into the peritoneum. From there, they migrate cephalad, boring through the parenchyma of the liver before finally settling in the biliary ducts. In 3 to 4 months they develop into adults, occupying the large biliary ducts primarily and laying more than 20,000 eggs per day. Adults can live up to 13 years in a human host if untreated 3.

The migrating metacercariae cause parenchymal liver damage, setting off a cascade of inflammatory and immune responses leading to a constellation of acute symptoms. Adult flukes may partially or completely obstruct the bile ducts, over time causing fibrosis, hypertrophy, and later dilation of the proximal biliary tree. Parasite load is typically positively correlated with the degree of liver damage 1.

Figure 1. Fasciola life cycle

Footnote: Immature eggs are discharged in the biliary ducts and passed in the stool (number 1). Eggs become embryonated in freshwater over ~2 weeks (number 2); embryonated eggs release miracidia (number 3), which invade a suitable snail intermediate host (number 4). In the snail, the parasites undergo several developmental stages (sporocysts [number 4a], rediae [number 4b], and cercariae [number 4c]). The cercariae are released from the snail (number 5) and encyst as metacercariae on aquatic vegetation or other substrates. Humans and other mammals become infected by ingesting metacercariae-contaminated vegetation (e.g., watercress) (number 6). After ingestion, the metacercariae excyst in the duodenum (number 7) and penetrate through the intestinal wall into the peritoneal cavity. The immature flukes then migrate through the liver parenchyma into biliary ducts, where they mature into adult flukes and produce eggs (number 8). In humans, maturation from metacercariae into adult flukes usually takes about 3–4 months; development of Fasciola gigantica may take somewhat longer than Fasciola hepatica.

Fascioliasis prevention

People can protect themselves by not eating raw watercress and other water plants, especially from Fasciola–endemic grazing areas. As always, travelers to areas with poor sanitation should avoid food and water that might be contaminated. Vegetables grown in fields that might have been irrigated with polluted water should be thoroughly cooked, as should viscera from potentially infected animals.

No vaccine is available to protect people against Fasciola.

In some areas of the world where fascioliasis is found (endemic), special control programs are in place or are planned. The types of control measures depend on the setting (such as epidemiologic, ecologic, and cultural factors). Strict control of the growth and sale of watercress and other edible water plants is important.

Fascioliasis symptoms

Human fascioliasis is usually recognized as an infection of the bile ducts and liver, but infection in other parts of the body can occur. Some infected people don’t ever feel sick.

Some people feel sick early on in the infection, symptoms can occur as a result of the Fasciola immature flukes migrating from the intestines to and through the liver. Symptoms can include gastrointestinal problems such as nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain/tenderness. Fever, rash, and difficulty breathing may occur. Symptoms from the acute (migratory) phase can start as soon as a few days after the exposure (typically, <1–2 weeks) and can last several weeks or months.

Some people feel sick during the chronic phase of the infection (after the parasite settles in the bile ducts), when adult flukes are in the bile ducts (the duct system of the liver). The symptoms, if any, associated with this phase can start months to years after the exposure. For example, symptoms can result from inflammation and blockage of bile ducts, which can be intermittent. Inflammation of the gallbladder and pancreas also can occur.

Both the acute and chronic phases of fascioliasis can be symptomatic or symptom free. Nonspecific clinical features of both phases can include the following:

- Fever, which can be intermittent;

- Malaise;

- Abdominal pain, in the right upper quadrant, epigastrium, or more diffuse/generalized;

- Other abdominal symptoms (such as anorexia, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, change in bowel habits, and weight loss) and signs such as hepatomegaly (an enlarged liver) and jaundice;

- Eosinophilia, which is more prominent and less variable during the acute phase than in the chronic phase;

- Anemia, especially in children; and

- Transaminitis (during the chronic phase, laboratory testing also can indicate hepatobiliary obstruction).

Acute fascioliasis (Acute phase)

The acute phase is also referred to as the migratory, invasive, hepatic, parenchymal, or larval phase. Immature larval flukes migrate through the intestinal wall, the peritoneal cavity, the liver capsule, and hepatic tissue and, ultimately, to the bile ducts. The acute phase lasts up to approximately 3 to 4 months and ends when the larvae reach and mature in the bile ducts. Larval migration, especially through the liver, can result in tissue destruction, inflammation, local or systemic toxic/allergic reactions, and internal bleeding. Symptoms, in addition to those listed above, can include urticaria, cough, and shortness of breath. This phase can be life threatening in sheep infected with large inocula of parasites. However, severe illness is uncommon in people, although some young children have intense abdominal pain.

Chronic fascioliasis (Chronic phase)

The chronic phase is also referred to as the biliary or adult phase. The chronic phase begins when immature larvae reach the bile ducts, mature into adult flukes, and start producing eggs. The eggs are passed from the bile ducts into the intestines and then into the feces. During this phase, the patient may be asymptomatic for months, years, or indefinitely. The only finding on routine blood testing might be peripheral eosinophilia, which typically is less prominent than during the acute phase.

Some experts differentiate between an asymptomatic latent phase and a symptomatic obstructive phase, which only some patients experience. The symptoms, if any, can be similar to those during the acute phase or can be more focal/discrete, such as clinical manifestations associated with cholangitis and biliary obstruction, which can be intermittent; cholecystitis and gallstones; or pancreatitis (also see below regarding ectopic infection). Fibrosis of the liver may occur.

On the basis of limited data, the life span of adult flukes in people might be 5 to 10 years or even longer (up to 13.5 years has been reported).

Involvement of ectopic sites

Fasciola parasites usually go to the liver and bile ducts. However, larval flukes also can migrate to ectopic (aberrant) sites, such as the pancreas, lungs, subcutaneous tissue, genitourinary tract, eyes, or brain. Fasciola parasites at ectopic sites may or may not mature into adult flukes. For example, subadult worms might emerge through the skin.

In addition, in the past, some cases of a syndrome known as Halzoun (a local, Middle Eastern term) —i.e., an acute hypersensitivity reaction involving the buccopharyngeal mucosa and upper respiratory tract in persons who ingested raw or undercooked sheep or goat liver—were attributed to temporary pharyngeal attachment of larval Fasciola flukes. However, whether Fasciola spp. (versus other parasites or agents) can cause this pharyngeal syndrome is unclear.

Fascioliasis diagnosis

Fascioliasis is exceedingly rare in the United States, but should be on the differential for any patient with the combination of abdominal pain (especially right upper quadrant), transaminitis, and marked peripheral eosinophilia. Even more suspicion should arise if a patient has traveled to endemic areas of Europe, Asia, or the Pacific, and their dietary history includes watercress ingestion or consumption of raw vegetables washed in potentially contaminated water. Often there is a delay in the diagnosis of this disease even in endemics areas due to its rarity and nonspecific acute symptoms 12.

Fascioliasis is diagnosed by examining stool (fecal) specimens under a microscope. The diagnosis is confirmed if Fasciola eggs are seen. However, egg production typically does not start until approximately 3 to 4 months after the exposure, whereas antibodies to the parasite may become detectable 2 to 4 weeks postexposure. Even during the chronic phase of infection, more than one stool specimen may need to be examined to find the parasite, especially in people with light infections.

Sometimes eggs are found by examining duodenal contents or bile.

Infected people don’t start passing eggs until they have been infected for several months; people don’t pass eggs during the acute phase of the infection. Therefore, early on, the infection has to be diagnosed in other ways than by examining stool. Even during the chronic phase of infection, it can be difficult to find eggs in stool specimens from people who have light infections.

A cautionary note is that Fasciola eggs can be difficult to distinguish on the basis of morphologic criteria from the eggs of Fasciolopsis buski, which is an intestinal fluke. This distinction has treatment implications. Infection with Fasciolopsis buski is treated with praziquantel, which typically is not effective therapy for fascioliasis.

False fascioliasis (pseudofascioliasis) refers to the presence of Fasciola eggs in the stool because of recent ingestion of contaminated liver (containing noninfective eggs). The potential for misdiagnosis can be avoided by having the patient follow a liver-free diet for several days before repeating stool examinations. In addition, serologic testing may be useful to exclude infection.

Certain types of blood tests can be helpful for diagnosing Fasciola infection, including routine blood work and tests that detect antibodies (an immune response) to the parasite.

Various types of immunodiagnostic tests for Fasciola have been developed. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) provides serologic testing using an immunoblot assay that detects IgG antibody to FhSAP2, a recombinant antigen derived from Fasciola hepatica. As always, test results should be interpreted in context, with expert consultation. In general, serologic testing can be useful:

- During the acute phase of infection, before the onset of egg production;

- During the chronic phase, in cases with low-level or sporadic production of eggs; and

- In cases of ectopic infection, in which eggs are not found in stool.

Other types of testing can provide supportive evidence (such as eosinophilia) or parasitologic confirmation (for example, if flukes are seen by imaging or by histopathology). The following are examples of additional types of testing:

- Routine blood work, including a complete blood count (with a differential white blood cell count) and blood chemistries;

- Abdominal imaging, such as ultrasonography, computerized axial tomography (CAT scan), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI scan), and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP);

- Ultrasound, cholangiogram, and ERCP are helpful during the biliary stage and may show the mobile, leaf-like flukes in biliary ducts or gallbladder, and are often associated with stones. Irregular common bile duct wall thickening, hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, and/or peri-portal lymphadenopathy are often present, especially in acute phase 13

- Rarely, one might also identify adult flukes in the biliary tree during endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatograhy (ERCP) during assessment in a patient with biliary obstruction. Occasionally capsular liver nodules can be seen by a surgeon during a diagnostic laparoscopy, but with no further clinical history are nonspecific. Liver biopsy is not routinely warranted as serology if much more specific, sensitive, and cost effective 13

- Computerized Tomography scan may show multiple, nodular, small (approximately 25 mm in diameter), branching, subcapsular lesions in the parenchyma of the liver. These tortuous tracks are left behind by the migrating parasites. Necrotic areas may be seen on scans utilizing inravaenous (IV) contrast 14. Subcapsular hematoma, capsular thickening, or parenchymal calcifications can also be seen 15

- Histopathologic examination of a biopsy specimen of liver or other pertinent tissue.

Serology has become the fastest and most efficient way to test for fascioliasis in recent years. Titers against fasciola antigens become positive during the early phase of parasite migration and are detectable 2 to 4 weeks following initial exposure to the host’s immune system. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) techniques have largely replaced stool ova and parasite testing because of its fast turn-around, sensitivity, and quantification 16. Serum fasciola antigen levels often positively correlate with the degree of infection 17. It also takes 5 to 7 weeks after initial infection before adult worms are mature enough to produce eggs; thus, there are no eggs in stool during the acute phase of the infection. Antigen levels positively correlate with the infectious burden. Successful treatment and extermination of the parasites correlate with a decline in the ELISA titers to fasciola antigens. Antibodies may still be detectable at low levels for years. The assay becomes undetectable in approximately 65% of patients one month following successful treatment. Some patients will have a low positive titer for life without any evidence of active infection 18.

Fascioliasis treatment

The drug of choice for treatment of fascioliasis is triclabendazole. The drug is given by mouth, usually in two doses (10 mg/kg daily). Most people respond well to the treatment.

Triclabendazole is an imidazole derivative and works by preventing the polymerization of tubulin into microtubules rendering cells incapable of producing their cytoskeletal structures. It is effective against all stages of fascioliasis with a cure rate of over 90% 19.

In February 2019, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved triclabendazole for treatment of fascioliasis in patients at least 6 years of age 20.

As with all medications, use of triclabendazole should be individualized.

Triclabendazole is given orally, with food, to improve absorption. According to the FDA-approved product label 20, the recommended dosage regimen (for patients at least 6 years of age) is two doses of 10 mg/kg given 12 hours apart.

Triclabendazole resistance has been documented, particularly in infected animals but also in some infected humans.

- Triclabendazole during pregnancy: There are no available data on the use of triclabendazole in pregnant women to inform a drug-associated risk for major birth defects, miscarriage, or adverse maternal or fetal outcomes.

- Triclabendazole during breastfeeding: According to the product label 20, there are no data on the presence of triclabendazole in human milk, the effects on the breastfed infant, or the effects on milk production. Published animal data indicate that triclabendazole is detected in goat milk when administered as a single dose to one lactating animal. When a drug is present in animal milk, it is likely that the drug will be present in human milk. The developmental and health benefits of breastfeeding should be considered along with the mother’s clinical need for triclabendazole and any potential adverse effects on the breastfed infant from the medication or from the underlying maternal condition.

- Triclabendazole in children: According to the product label 20, which addresses treatment of fascioliasis, the safety and effectiveness of triclabendazole have been established for pediatric patients aged 6 years and older (the age group for which the drug has been approved by FDA for treatment of fascioliasis) but have not been established for younger patients.

Additional perspective about therapy

On the basis of limited data, nitazoxanide might be effective therapy in some patients. The drug is given orally, with food. The dosage regimen for adults is 500 mg oral twice a day for 7 days.

Praziquantel, which is active against most trematodes (flukes), typically is not active against Fasciola parasites. Therefore, praziquantel therapy is not recommended for fascioliasis.

In some patients who have biliary tract obstruction, manual extraction of adult flukes (e.g., via endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography [ERCP]) may be indicated.

- Arjona R, Riancho JA, Aguado JM, Salesa R, González-Macías J. Fascioliasis in developed countries: a review of classic and aberrant forms of the disease. Medicine (Baltimore). 1995 Jan;74(1):13-23.[↩][↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Fasciola Epidemiology & Risk Factors. https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/fasciola/epi.html[↩]

- Kaya M, Beştaş R, Cetin S. Clinical presentation and management of Fasciola hepatica infection: single-center experience. World J. Gastroenterol. 2011 Nov 28;17(44):4899-904.[↩][↩]

- Soliman MF. Epidemiological review of human and animal fascioliasis in Egypt. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2008 Jun 01;2(3):182-9.[↩][↩]

- Weisenberg SA, Perlada DE. Domestically acquired fascioliasis in northern California. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2013 Sep;89(3):588-91.[↩]

- Mas-Coma S. Epidemiology of fascioliasis in human endemic areas. J. Helminthol. 2005 Sep;79(3):207-16.[↩]

- Bayhan Gİ, Batur A, Taylan-Özkan A, Demirören K, Beyhan YE. A pediatric case of Fascioliasis with eosinophilic pneumonia. Turk. J. Pediatr. 2016;58(1):109-112.[↩]

- Prueksapanich P, Piyachaturawat P, Aumpansub P, Ridtitid W, Chaiteerakij R, Rerknimitr R. Liver Fluke-Associated Biliary Tract Cancer. Gut Liver. 2018 May 15;12(3):236-245.[↩]

- Kim AJ, Choi CH, Choi SK, Shin YW, Park YK, Kim L, Choi SJ, Han JY, Kim JM, Chu YC, Park IS. Ectopic Human Fasciola hepatica Infection by an Adult Worm in the Mesocolon. Korean J. Parasitol. 2015 Dec;53(6):725-30.[↩]

- Saleha AA. Liver fluke disease (fascioliasis): epidemiology, economic impact and public health significance. Southeast Asian J. Trop. Med. Public Health. 1991 Dec;22 Suppl:361-4.[↩]

- Hawramy TA, Saeed KA, Qaradaghy SH, Karboli TA, Nore BF, Bayati NH. Sporadic incidence of Fascioliasis detected during hepatobiliary procedures: a study of 18 patients from Sulaimaniyah governorate. BMC Res Notes. 2012 Dec 21;5:691.[↩]

- Cabada MM, White AC. New developments in epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment of fascioliasis. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2012 Oct;25(5):518-22.[↩]

- Sezgin O, Altintaş E, Dişibeyaz S, Saritaş U, Sahin B. Hepatobiliary fascioliasis: clinical and radiologic features and endoscopic management. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2004 Mar;38(3):285-91.[↩][↩]

- Teke M, Önder H, Çiçek M, Hamidi C, Göya C, Çetinçakmak MG, Hattapoğlu S, Ülger BV. Sonographic findings of hepatobiliary fascioliasis accompanied by extrahepatic expansion and ectopic lesions. J Ultrasound Med. 2014 Dec;33(12):2105-11.[↩]

- Dias LM, Silva R, Viana HL, Palhinhas M, Viana RL. Biliary fascioliasis: diagnosis, treatment and follow-up by ERCP. Gastrointest. Endosc. 1996 Jun;43(6):616-20.[↩]

- Gonzales Santana B, Dalton JP, Vasquez Camargo F, Parkinson M, Ndao M. The diagnosis of human fascioliasis by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using recombinant cathepsin L protease. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7(9):e2414[↩]

- Hassan MM, Saad M, Hegab MH, Metwally S. Evaluation of circulating Fasciola antigens in specific diagnosis of fascioliasis. J Egypt Soc Parasitol. 2001 Apr;31(1):271-9.[↩]

- Shehab AY, Hassan EM, Basha LM, Omar EA, Helmy MH, El-Morshedy HN, Farag HF. Detection of circulating E/S antigens in the sera of patients with fascioliasis by IELISA: a tool of serodiagnosis and assessment of cure. Trop. Med. Int. Health. 1999 Oct;4(10):686-90.[↩]

- Villegas F, Angles R, Barrientos R, Barrios G, Valero MA, Hamed K, Grueninger H, Ault SK, Montresor A, Engels D, Mas-Coma S, Gabrielli AF. Administration of triclabendazole is safe and effective in controlling fascioliasis in an endemic community of the Bolivian Altiplano. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2012;6(8):e1720[↩]

- https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2019/208711s000lbl.pdf[↩][↩][↩][↩]