Fertility preservation

Fertility preservation is a type of procedure aim to preserve fertility for people who wish to have children in the future and are at risk of losing their fertility. Infertility is functionally defined as the inability to conceive after 1 year of intercourse without contraception. For people who have been diagnosed with cancer, fertility preservation is an important consideration if there is a chance that their cancer treatment may affect their fertility. The likelihood that cancer treatment will harm your fertility depends on the type and stage of cancer, the type of cancer treatment, and your age at the time of treatment. Fortunately, there are now many fertility preservation options available to men and women with cancer and there are many people who have been able to start a family after cancer treatment.

Fertility preservation is beneficial in various circumstances, including where:

- You have a serious illness such as cancer and have to undergo treatment that may result in the loss of fertility.

- You want to have children but are not ready to do so now and are concerned about the effects ageing might have on your chances of having a family.

- You are at risk of early menopause.

- You have a genetic disorder that may limit fertility.

Increasingly, fertility preservation is now also being used for non-medical purposes. Egg freezing for social reasons has seen a rise in demand in recent years. Transgender people are also utilizing fertility preservation in order to have children in the future.

The ability to freeze (cryopreserve) sperm and embryos has been technically feasible and a widely practised procedure for more than a decade. Freezing eggs and ovarian tissue, however, has been much more difficult for a wide range of physiological reasons. Much scientific work has gone into developing the techniques to successfully cryopreserve mature oocytes and ovarian tissue. With the advances made so far, fertility specialists can now offer such treatment in selected cases.

Fertility preservation in cancer

If you’re being treated for cancer, you might have questions about fertility preservation. The estimated number of cancer survivors of reproductive age in the United States is now approaching half a million 1. Although cancer treatments have evolved to cause fewer harmful side effects in these patients, radiation therapy and many chemotherapy agents can still damage fertility.

Certain cancer treatments can harm your fertility. The effects might be temporary or permanent. Male and female fertility may be transiently or permanently affected by cancer treatment or only become manifest later in women through premature ovarian failure. The American Society of Clinical Oncology panel wishes to emphasize that female fertility may be compromised despite maintenance or resumption of cyclic menses. Regular menstruation does not guarantee normal fertility as any decrease in ovulatory reserve may result in a lower chance of subsequent conception and higher risk of early menopause. Even if women are initially fertile after cancer treatment, the duration of their fertility may be shortened by premature menopause.

Rates of permanent infertility and compromised fertility after cancer treatment vary and depend on many factors. The effects of chemotherapy and radiation therapy depend on the drug or size/location of the radiation field, dose, dose-intensity, method of administration (oral versus intravenous), disease, age, sex, and pretreatment fertility of the patient 2. Male infertility can result from the disease itself (best documented in patients with testicular cancer and Hodgkin’s lymphoma), anatomic problems (eg, retrograde ejaculation or anejaculation), primary or secondary hormonal insufficiency, or more frequently, from damage or depletion of the germinal stem cells. The measurable effects of chemotherapy or radiotherapy include compromised sperm number, motility, morphology, and DNA integrity. In females, fertility can be compromised by any treatment that decreases the number of primordial follicles, affects hormonal balance, or interferes with the functioning of the ovaries, fallopian tubes, uterus, or cervix. Anatomic or vascular changes to the uterus, cervix, or vagina from surgery or radiation may also prevent natural conception and successful pregnancy, requiring assisted reproductive technology or use of a gestational carrier.

Cancer treatments and their effects might include:

- Surgery. Fertility can be harmed by the surgical removal of the testicles, uterus or ovaries.

- Chemotherapy. The effects depend on the drug and the dose. The most damage is caused by drugs called alkylating agents and the drug cisplatin. Younger women who receive chemotherapy are less likely to become infertile than are older women.

- Radiation. Radiation can be more damaging to fertility than chemotherapy, depending on the location and size of the radiation field and the dose given. For example, high doses of radiation can destroy some or all of the eggs in the ovaries.

- Other cancer medications. Hormone therapies used to treat certain cancers, including breast cancer in women, can affect fertility. But the effects are often reversible. Once treatment stops, fertility might be restored.

The most frequent cause of impaired fertility in male cancer survivors is chemotherapy- or radiation-induced damage to sperm. The fertility of female survivors may be impaired by any treatment that damages immature eggs, affects the body’s hormonal balance, or injures the reproductive organs.

If you are planning cancer treatment and want to preserve your fertility, talk to your doctor and a fertility specialist as soon as possible. A fertility specialist can help you understand your options, answer questions and serve as your fertility advocate during your treatment.

Your fertility can be damaged by a single cancer therapy session, and for women, some methods of fertility preservation are typically done during certain phases of the menstrual cycle. Ask if you will need to delay cancer treatment to take fertility preservation steps and, if so, how this might affect your cancer.

How do I determine the best fertility preservation option for me?

Your medical team will consider the type of cancer you have, your treatment plan and the amount of time you have before treatment begins to help determine the best approach for you.

The diagnosis of cancer and the treatment process can be overwhelming. However, if you’re concerned about how cancer treatment might affect your fertility, you have options. Don’t wait. Getting information about fertility preservation methods before you begin cancer treatment can help you make an informed choice.

Can fertility preservation interfere with successful cancer therapy or increase the risk of recurring cancer?

There’s no evidence that current fertility preservation methods can directly compromise the success of cancer treatments. However, you could compromise the success of your treatment if you delay surgery or chemotherapy to pursue fertility preservation.

There appears to be no increased risk of cancer recurrence associated with most fertility preservation methods. However, there is a concern that reimplanting frozen tissue could reintroduce cancer cells — depending on the type and stage of cancer.

Should I have children after I’ve had cancer?

After a cancer diagnosis, many people wonder if they should even think about having children. They may question whether a genetic factor might have caused them to get cancer and if they might pass this cancer gene to their children. But only about 5% to 10% of cancers have a strong link to a gene that is passed on from parent to child.

Survivors also may worry that treatment with chemo or radiation could cause birth defects or other health problems for future children. Studies have found that babies conceived after cancer treatment don’t have birth defects or health problems any more often than babies whose parent didn’t have cancer. But problems are more likely if a baby is conceived during or too soon after cancer treatment, so it’s important to know how long to wait before trying to have a baby.

It helps to get as much information as you can before you make a decision that will affect the rest of your life as much as this one will. You might want to discuss these concerns with a genetic counselor, geneticist, reproductive specialist, and/or a mental health professional.

Depression, anxiety, and stress may affect your ability to think as clearly as you would like about your reproductive choices. Talk about these issues and concerns with the people whose opinions you value and trust – your spouse or partner, health care team, family, close friends, clergy, etc. There are support groups as well as health professionals who deal with fertility issues for people with cancer. Ask your doctor to refer you to one of these specialists.

Do children of cancer survivors have higher risks of getting cancer?

Research shows that no unusual cancer risk has been identified in the offspring of cancer survivors. The exception to this is in families who have true genetic cancer syndromes. If there’s a lot of cancer in your family, you might want to check with a genetic counselor to see if any of your potential children would have a higher than usual chance of having cancer.

Are the rates of birth defects higher in children born to cancer survivors who have had treatments like chemo and/or radiation therapy than in the general public?

So far studies suggest that children born to cancer survivors are only very slightly more at risk than others in the general public to have birth defects. In a very large study in Sweden and Denmark, over a period of 20 years, over 96% of children born after a father’s cancer treatment were healthy. There was a very small increase in risk of a major birth defect (about 1% if a child was conceived within two years of the father’s treatment).

After cancer treatment, how long should I wait to conceive?

There is no set time. It’s very important to discuss this with your doctor to find out what’s best for you. One study found a slightly higher rate of birth defects in children conceived within 6 to 24 months after a man’s cancer treatment.

Is pregnancy safe after cancer?

Despite concerns that pregnancy could cause cancer to return, studies to date have not shown this to be true for any type of cancer. Breast cancer is the type most people worry about because of the hormone changes that happen during pregnancy. So far, studies suggest that survival rates in women who become pregnant after breast cancer are as good as in women who do not. But this issue is still being studied. Every cancer is different, so it’s not possible to say for sure that it’s safe for all cancer survivors to become pregnant.

You also need to know that pregnancy could be a problem if cancer treatment has damaged your heart, lungs, or other organs. When organs are damaged, the added physical stress of a pregnancy can lead to serious health problems for the mother and the growing fetus.

Radiation that reaches the uterus, especially if it was done when the woman was a child, can limit the ability of the uterus to stretch as the fetus grows. This creates an increased risk of a premature or low birth-weight baby, or even having a miscarriage.

If you are thinking about getting pregnant after cancer, it’s a good idea to first see a specialist in high-risk obstetrics to find out if you have any health risks because of your cancer treatment. Your cancer doctor can also talk with you about how your health, your cancer and cancer treatment, and your risk of cancer coming back might affect pregnancy and parenthood.

If I didn’t act to preserve my fertility before cancer treatment, is it too late or do I still have options?

The answer to this question depends on your type of cancer and treatment. This is something you need to discuss with your oncologist. You may need to see a fertility specialist.

After cancer, how will I know if I need to see a fertility specialist?

It’s best to discuss fertility with your oncologist first, because everyone’s cancer diagnosis and treatment is different. But if you’ve had trouble conceiving for 6 months, despite having sex at the right times of the month, you might have a fertility problem and should consider seeing a specialist.

Do fertility drugs cause cancer?

A few early studies suggested a link between some fertility drugs and cancer, but recent studies suggest there’s no direct link between the use of fertility drugs and breast, uterine, ovarian, or any hormone-related cancer. If you are getting any of the drugs that stimulate eggs, talk with your doctor or nurse about their short- and long-term risks and side effects.

How long can embryos, eggs, sperm and tissues be frozen?

Indefinitely. Samples have been stored for decades without damage. Most of the risk occurs in the freezing and thawing processes, so once they are frozen they can be stored for many years.

What role does age play in fertility for men after cancer?

In general, a man’s fertility will begin to decline between ages 40 and 50. But cancer treatment can affect fertility in men of all ages, including boys who have not yet reached puberty.

Chemo may be more damaging to sperm production in men who are over 40.

What role does age play in fertility for women after cancer?

For women, getting older is a factor in fertility whether you have cancer or not. The older you are, the harder it is to get pregnant. Many do not realize that fertility declines rapidly after age 35, even in healthy women. Cancer treatments that cause premature menopause affect a woman’s fertility.

Research suggests that the younger a woman is when she gets damaging cancer treatments, the less likely it is that she will become infertile. This may be because a younger woman has more eggs in reserve, so more eggs are likely to remain alive after treatment.

If it looks like I am fertile after treatment, should I use the sperm I froze before treatment?

Make this decision with the help of a fertility specialist. Most fertility specialists recommend that cancer survivors who recover fertility should try to conceive naturally with the sperm they are producing, but more research is needed in this area.

If it looks like I am fertile after treatment, should I use the embryos or eggs I froze before treatment?

Make this decision with the help of a fertility specialist or a reproductive endocrinologist. Most fertility specialists would recommend that cancer survivors who recover fertility should try to conceive naturally. There’s no proof of an increased risk of birth defects in children born after cancer treatment. If you have trouble getting pregnant naturally, however, your frozen eggs or embryos are a great backup.

Do cancer survivors have trouble adopting because of their medical history?

One study did show a bias of adoption agencies against allowing adoptions by cancer survivors. Most adoption agencies say they do not rule out cancer survivors as parents. But they often require medical exams and a letter from an oncologist saying that the cancer survivor has a good prognosis (outlook for survival).

Some agencies may require a cancer survivor be cancer-free for 5 years before applying for adoption. In recent years, all but a few countries have stopped allowing cancer survivors to adopt internationally.

Some discrimination clearly does occur both in domestic and international adoption. Yet, most cancer survivors who want to adopt can do so. You may be able to find an agency that has experience working with cancer survivors.

Fertility preservation for women with cancer

You should discuss your fertility preservation options with your doctor. Be sure that you understand the risks and chances of success of any fertility preservation option you are interested in, and keep in mind that no method works 100% of the time. Married women and those with long-term partners might want to include them in these discussions and decisions. Even married women should be aware that embryos created with a husband are often unable to be used if a divorce occurs. A woman has the most control over her future fertility if she freezes unfertilized eggs or ovarian tissue.

After cancer treatment, a woman’s body may recover naturally and produce mature eggs that can be fertilized. The medical team may recommend waiting anywhere from 6 months to 2 years before trying to get pregnant. Waiting 6 months may reduce the risk of birth defects from eggs damaged by chemotherapy or other treatments. The 2-year period is generally based on the fact that the risk of the cancer coming back (recurring) is usually highest in the first 2 years after treatment. The length of time depends on the type of cancer and the treatment used.

But women who have had chemo or radiation to the pelvis are also at risk for sudden, early menopause even after they start having menstrual cycles again. Menopause may start 5 to 20 years earlier than expected. Because of this, women should talk to their doctors about how long they should wait to try to conceive and why they should wait. It’s best to have this discussion before going on with a pregnancy plan.

How can women preserve fertility before cancer treatment?

Women who are about to undergo cancer treatment have various options when it comes to fertility preservation. For example 3:

- Embryo cryopreservation. This procedure involves harvesting eggs, fertilizing them and freezing them so they can be implanted at a later date. Research shows that embryos can survive the freezing and thawing process up to 90% of the time.

- Egg freezing (oocyte cryopreservation). In this procedure, you’ll have your unfertilized eggs harvested and frozen. Human eggs don’t survive freezing as well as human embryos.

- Radiation shielding. In this procedure, small lead shields are placed over the ovaries to reduce the amount of radiation exposure they receive.

- Ovarian transposition (oophoropexy). During this procedure, the ovaries are surgically repositioned in the pelvis so they’re out of the radiation field when radiation is delivered to the pelvic area. However, because of scatter radiation, ovaries aren’t always protected. After treatment, you might need to have your ovaries repositioned again to conceive.

- Surgical removal of the cervix. To treat early-stage cervical cancer, a large cone-shaped section of the cervix, including the cancerous area, is removed (cervical conization). The remainder of the cervix and the uterus are preserved. Alternatively, a surgeon can partially or completely remove the cervix and the connective tissues next to the uterus and cervix (radical trachelectomy).

Fertility-sparing surgery (for ovarian cancer)

This type of surgery might be an option in young women with ovarian cancer in only one ovary. The cancer must be one of the types that’s slow-growing and less likely to spread, like borderline, low malignant potential, germ cell tumors, or stromal cell tumors (typically Grade 1 and some Grade 2 epithelial ovarian cancers).

In this case, the surgeon can remove just the ovary with cancer, leaving the healthy ovary and the uterus (womb) in place. Studies have found that this does not affect long-term survival, and allows future fertility. If there’s a risk of the cancer coming back, the remaining ovary may be removed later, after the woman has finished having children.

GnRH agonist treatment (ovarian suppression)

Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists are long-acting hormone drugs that can be used to make a woman go into menopause for a short time. The goal of this treatment is to shut down the ovaries during cancer treatment to help protect them from damaging effects. The hope is that reducing activity in the ovaries during treatment will reduce the number of eggs that are damaged, so women will resume normal menstrual cycles after treatment. These hormones are usually given as a monthly shot starting a couple of weeks before chemo or pelvic radiation therapy begins. GnRH treatment is given the entire time a woman receiving cancer treatment and is available in injections that last either 1 month or 3 months.

Studies suggest that this method might help prolong fertility in some women, especially those 35 and younger, but results are not at all clear. Most research studies have not found it to improve later pregnancy rates. This treatment is considered experimental. If this treatment is used, it’s best done with a back-up method of preserving fertility like embryo freezing.

The injections are expensive and the drugs can weaken a woman’s bones if used for more than 6 months. The most common side effect is hot flashes. GnRH treatment can be useful to prevent heavy menstrual bleeding during chemo, especially for women with leukemia.

Ovarian tissue freezing

All or part of one ovary is removed by laparoscopy (a minor surgery where a thin, flexible tube is passed through a small cut near the navel to reach and look into the pelvis). The ovarian tissue is usually cut into small strips, frozen, and stored.

After cancer treatment, the ovarian tissue can be thawed and placed in the pelvis. Once the transplanted tissue starts to function again, the eggs can be collected and fertilized in the lab. In another approach, the whole ovary is frozen with the idea of putting it back in the woman’s body after treatment, but this has not yet been done in humans.

Ovarian tissue removal does not usually require a hospital stay. It can be done either before or after puberty. Still, it’s experimental and has produced a small number of live births so far. Doctors are studying it now to learn the best methods for success. Faster freezing of the tissue (vitrification) has greatly improved outcomes over older, slow-freezing methods.

The ovarian tissue does grow a new blood supply and produces hormones after it’s transplanted, but some of the tissue usually dies and it may only last for a few months to several years. Because they last such a short time, ovarian tissues are usually only transplanted when a woman is ready to try for a pregnancy.

At this time, ovarian tissue freezing and transplant is not recommended for women with blood cancers (such as leukemias or lymphomas) or ovarian cancer due to the risk of putting cancer cells back in the body with the frozen tissue.

Ovarian tissue freezing costs vary a lot, so you will want to ask about the freezing and annual storage costs as well as removal and transplant expenses. In some patients, ovarian tissue can be removed as part of another necessary surgery so that some of the cost is covered by insurance.

Ovarian transposition

Ovarian transposition means moving the ovaries away from the target zone of radiation treatment. It’s a standard option for girls or women who are going to get pelvic radiation. It can be used either before or after puberty.

This procedure can often be done as outpatient surgery and does not require staying in the hospital (unless it is being done as part of a larger operation). Surgeons will usually move the ovaries above and to the side of the central pelvic area.

The success rates for this procedure have usually been measured by the percentage of women who regain their menstrual periods, not by rates of a live birth. Typically, about half the women start menstruating again.

It’s hard to estimate the costs of ovarian transposition, since this procedure may sometimes be done during another surgery that is covered by insurance. It’s usually best to move the ovaries just before starting radiation therapy, since they tend to fall back into their old places over time.

Radical trachelectomy

Radical trachelectomy is an option for cervical cancer patients who have very small, localized tumors. The cervix is removed but the uterus and the ovaries are left, and the uterus is connected to the upper part of the vagina. A special band or stitch is wrapped around the bottom of the uterus to tighten the opening while still allowing blood from your period to flow out and sperm to enter to fertilize an egg. Trachelectomy is a surgery used to treat early cervical cancer, so insurance should cover some or all of the costs. Talk to your doctor about this.

Trachelectomy appears to be just as successful as radical hysterectomy (removal of the uterus and cervix) in treating cervical cancer in certain women with small tumors. Women can become pregnant after the surgery, but are at risk for miscarriage and premature birth because the opening to the uterus may not close as strongly or tightly as before. These women will need specialized obstetrical care while they are pregnant, and the baby will need to be delivered by Cesarean section (C-section).

Progesterone therapy for early-stage uterine cancer

Younger women sometimes have endometrial hyperplasia (pre-cancerous changes in the cells that line the uterus) or an early-stage, slow-growing cancer of the lining of the uterus (adenocarcinoma). The usual treatment would be hysterectomy (surgery to remove the uterus). However, women with stage 1 Grade 1 endometrial cancer who still want to have a child can be treated instead with the hormone progesterone, via an intrauterine device or as a pill. Up to three-quarters of women respond well, allowing them time to try to get pregnant. Most have removal of the uterus, fallopian tubes, and both ovaries after giving birth. About 25% of women with hyperplasia, and up to 40% with uterine cancer have a recurrence within several years of progesterone therapy. Since they also have a high risk of ovarian cancer, many oncologists believe young women with uterine cancer should not freeze ovarian tissue and put it back into their bodies later on.

Options for women who are not fertile after cancer treatment

Adoption

Adoption is usually an option for anyone who wants to become a parent. Adoption can take place within your own country through a public agency or by a private arrangement, or internationally through private agencies. Some agencies specialize in placing children with special needs, older children, or siblings.

Most adoption agencies state that they do not rule out cancer survivors as potential parents. But agencies often require a letter from your doctor stating that you are cancer-free and can expect a healthy lifespan and a good quality of life. Some agencies or countries require a period of being off treatment and cancer-free before a cancer survivor can apply for adoption. Five years seems to be an average length of time.

There’s a lot of paperwork to complete during the adoption process, and at times it can seem overwhelming. Many couples find it helpful to attend adoption or parenting classes before adopting. These classes can help you understand the adoption process and give you a chance to meet other couples in similar situations. The process takes different lengths of time depending on the type of adoption you choose. Most adoptions can be completed in 1 to 2 years.

Costs of adopting vary greatly, from less than $4,000 (for a public agency, foster care, or special needs adoption) up to $50,000 (for some international adoptions, including travel costs).

You might be able to find an agency that has experience working with cancer survivors. Some discrimination clearly does occur both in domestic and international adoption. Yet, most cancer survivors who want to adopt can do so.

Donor eggs

Donor egg is an option for women who have a healthy uterus and are cleared by their doctors to carry a pregnancy but do not have any eggs or have healthy eggs to conceive with their own eggs. The process involves in vitro fertilization (IVF), in which mature eggs are removed from a woman’s ovaries, fertilized with sperm in the lab, and then put in a woman’s uterus to develop. In donor egg, eggs from a donor are used. Success rates for IVF are measured as the percent of cycles that end in the birth of a live baby. After age 40, this success rate goes way down if a woman uses her own eggs.

Older women or cancer survivors may have more chance of a having a baby by using donated eggs. Donated eggs come from women who have volunteered to go through a cycle of hormone stimulation and have their eggs collected. In the United States, donors can be known or anonymous. Some couples find their own donors through programs at infertility clinics or on the Internet. Some women have a sister, cousin, or close friend who is willing to donate her eggs without payment. Most egg donors are paid, however. There are also frozen egg banks available in which a women purchases a group of frozen eggs that are then send to a fertility center for IVF.

Per regulations, egg donors are carefully screened for sexually transmitted infections and genetic diseases. Every egg donor should also be screened by a mental health professional familiar with the egg donation process. These screenings are just as important for donors who are friends or family members. For known donors, everyone also needs to agree on what the donor’s relationship with the child will be, and be certain that the donor was not pressured emotionally or financially to donate her eggs. You want to be sure that everyone agrees about what the child will or will not be told in the future.

The success of the egg donation depends on carefully timing hormone treatment (to prepare the lining of the uterus) to be ready for an embryo to be placed inside. The eggs are taken from the donor and fertilized with the sperm. Embryos are then transferred to the recipient to produce pregnancy. If the woman receiving the donor eggs has ovarian failure (she’s in permanent menopause), she must take estrogen and progesterone to prepare her uterus for the embryo(s). After the transfer, the woman will continue to need hormone support until the placenta develops and can produce its own hormones.

Egg donation is often a successful treatment for infertility in women who can no longer produce healthy eggs. The entire process of donating eggs, fertilizing them with sperm, and implanting them usually takes 6 to 8 weeks per cycle. The major health risk for cancer survivors and babies is the risk of having twins or triplets. Responsible programs may transfer only 1 or 2 embryos to reduce this risk, freezing extras for a future cycle. The price of a donor egg cycle should include the price of IVF plus any payment to the egg donor, but it’s good to find out all the costs beforehand.

Donor embryos

Any woman who has a healthy uterus and can maintain a pregnancy can have in vitro fertilization (IVF) with donor embryos. IVF; a fertilized egg, an embryo, is put in a woman’s uterus to develop. This approach lets a couple experience pregnancy and birth together, but neither parent will have a genetic relationship to the child. Embryo donations usually come from a couple who has had IVF and used assisted reproductive technology and has extra frozen embryos. When that couple has fulfilled their family goals or for some other reason chooses not to use those frozen embryos, they might decide to donate them.

One problem with this option is that the couple donating the embryo may not agree to have the same types of genetic testing as is usually done for egg or sperm donors, and they may not want to supply a detailed health history. On the other hand, the embryos are free, so the cancer survivor only needs to pay the cost of getting her uterus ready and having the embryo placed.However, the costs are usually less for the intended parents than using an egg donor. Still, legal and medical fees can mount up.

Most women who use the donor embryo procedure must get hormone treatments to prepare the lining of the uterus and ensure the best timing of the embryo transfer. The embryo is thawed and transferred to the woman’s uterus to develop and grow. After the embryo is transferred, the woman stays on hormone support until blood work shows that the placenta is making hormones on its own.

There’s no published research on the success rates of embryo donation, so it’s important that you research the IVF success rates of the centers you may use.

Surrogacy

Surrogacy is an option for women who cannot carry a pregnancy, either because they no longer have a working uterus, or would be at high risk for a health problem if they got pregnant. There are 2 types of surrogate mothers:

- A gestational carrier is a healthy female who receives the embryos created from the egg and sperm of the intended parents or from egg or sperm donors. The gestational carrier does not contribute her own egg to the embryo and has no genetic relationship to the baby.

- A traditional surrogate is usually a woman who becomes pregnant through artificial insemination with the sperm of the male in the couple (or a sperm donor) who will raise the child. She gives her egg (which is fertilized with his sperm in the lab), and carries the pregnancy. She is the genetic mother of the baby.

Surrogacy can be a legally complicated and expensive process. Surrogacy laws vary, so it’s important to have an attorney help you make the legal arrangements with your surrogate. You should consider the laws of the state where the surrogate lives, the state where the child will be born, and the state where you live. It’s also very important that the surrogate mother be evaluated and supported by an expert mental health professional as part of the process. Very few surrogacy agreements go sour, but when they do, typically this step was left out.

Fertility preservation for men with cancer

Cancer or more often cancer treatments, can interfere with some parts of the reproductive process and affect your ability to have children. Different types of treatments can have different effects.

How cancer treatments can affect fertility in men:

- Hormone production can be disrupted

- Testicles may not make healthy sperm or any sperm at all

- The process of sperm ejaculation can be disrupted

Cancer, or more often cancer treatments, can interfere with some parts of the reproductive process and affect your ability to have children. Different types of treatments can have different effects.

Ideally, discussions about fertility preservation should take place before cancer treatments begin. Doctors don’t always remember to bring this up, so you might have to bring it up yourself.

Many types of chemotherapy and radiation therapy involving the testicles and/or pelvic areas can result in sperm DNA damage. This DNA damage can potentially cause failure to fertilize the egg or pregnancies that end in miscarriage for the couple. If a child is conceived using sperm with damaged DNA, the sperm genetic abnormalities can be inherited by the child. These DNA changes can result in serious and even life-threatening abnormalities in that child.

It is very important to discuss with your doctor if you can have unprotected sex both during and after cancer treatment. Your medical team may recommend waiting anywhere from 6 months to 2 years before trying to have a child by natural means or resuming unprotected sexual intercourse. It’s best to have this discussion with your medical team and with your partner before planning attempts to achieve a pregnancy or resuming unprotected sexual activity. Your treatment history, including chemotherapy drugs and dosages administered and radiation location and dosages given, will all be considered.

How chemotherapy can affect male fertility

During puberty (usually around age 13 to 14), a boy’s testicles start making sperm, and they normally will keep doing so for the rest of his life. Cancer treatment during childhood, however, can damage testicles and affect their ability to produce sperm.

Chemotherapy (chemo) works by killing cells in the body that are dividing quickly. Since sperm cells divide quickly, they are an easy target for damage by chemo. Permanent infertility can result if all the immature cells in the testicles that divide to make new sperm (spermatogonial stem cells) are damaged to the point that they can no longer produce maturing sperm cells.

The risk of the chemo causing infertility varies depending on:

- The patient’s age. For example, men older than 40 may be less likely to recover their fertility after treatment.

- The type of drug(s) used. Some drugs are more likely to affect fertility than others (see lists below).

- The doses of drugs given. The higher the doses of chemo, the longer it takes for sperm production to get back to normal after treatment, and the more likely it is to stop.

After chemo treatment, sperm production slows down or might stop altogether. Some sperm production usually returns in 1 to 4 years, but it can take up to 10 years. If sperm production has not recovered within 4 years, it’s less likely to return.

Chemo drugs that are linked to the highest risk of infertility in males include:

- Actinomycin D

- Busulfan

- Carboplatin

- Carmustine

- Chlorambucil

- Cisplatin

- Cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan®)

- Cytarabine

- Ifosfamide

- Lomustine

- Melphalan

- Nitrogen mustard (mechlorethamine)

- Procarbazine

Higher doses of these drugs are more likely to cause permanent fertility changes , and combinations of drugs can have greater effects. The risks of permanent infertility are even higher when males are treated with both chemo and radiation therapy to the belly (abdomen) or pelvis.

Some drugs, such as those listed here, have a lower risk of causing infertility in males, as long as they are given in low to moderate doses:

- 5-fluorouracil (5-FU)

- 6-Mercaptopurine (6-MP)

- Bleomycin

- Cytarabine (Cytosar®)

- Dacarbazine

- Daunorubicin (Daunomycin®)

- Doxorubicin (Adriamycin®)

- Epirubicin

- Etoposide (VP-16)

- Fludarabine

- Methotrexate

- Mitoxantrone

- Thioguanine (6-TG)

- Thiotepa

- Vinblastine (Velban®)

- Vincristine (Oncovin®)

Talk to your doctor about the chemo drugs you will get and the fertility risks that come with them.

How targeted and immune therapies can affect male fertility

Targeted drugs attack cancer cells differently from standard chemo drugs. These drugs have been used a lot more in recent years, but little is known about their effects on fertility or problems during pregnancy. The small amount of data available on a group of targeted drugs called tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), such as imatinib (Gleevec®), suggest that pregnancies started by young males getting tyrosine kinase inhibitors are probably not at an increased risk of complications or birth defects. Still, there’s not enough research available to know that it’s safe to start a pregnancy while taking these drugs. At this time, the recommendation is if you are taking tyrosine kinase inhibitors talk to a doctor before starting a pregnancy.

Males taking thalidomide or lenalidomide have a high risk of causing birth defects in a fetus exposed to these drugs, which can stay in semen for a few months after treatment ends. Oncologists recommend that males and any sexual partner who is able to get pregnant use extremely effective forms of birth control, for example a condom for the man and a long-acting hormone contraceptive or IUD for the woman.

How hormone therapy can affect male fertility

Some hormone therapies used to treat prostate or other cancers can affect sperm production and your ability to have a child. These drugs can also cause sexual side effects, such as a lower sex drive and problems with erections, while patients are taking them. The decrease in sperm production and the sexual side effects usually start to improve once these drugs are stopped.

How bone marrow or stem cell transplant can affect male fertility

Having a bone marrow or stem cell transplant usually means the patient will receive high doses of chemo and sometimes radiation to the whole body before the procedure. In most cases, these procedures have the side of effect of permanently preventing a man from making sperm. This results in life-long changes to fertility.

How radiation therapy can affect male fertility

Radiation treatments use high-energy rays to kill cancer cells. Radiation aimed directly at testicles, or to nearby pelvic areas can affect a male’s fertility. Radiation at high doses kills the stem cells that produce sperm.

Radiation is aimed directly at the testicles to treat some types of testicular cancer and childhood leukemia. Young males with seminoma, a type of cancer of the testicle, may have radiation to the groin area, very close to their remaining testicle. Even when a man gets radiation to treat a tumor in his abdomen (belly) or pelvis, his testicles may still end up getting enough radiation to harm sperm production.

Sometimes radiation to the brain affects the hypothalamus and pituitary gland. The hypothalamus and pituitary gland work together to produce two important hormones called LH and FSH. These hormones are released into the bloodstream and signal the testicles to make testosterone and also to produce sperm. When cancer or cancer treatments interfere with these signals, sperm production can be decreased and infertility can occur.

You may be fertile when you’re getting radiation treatments, but your sperm may be damaged by exposure to the radiation.

For this reason, it is important to talk to your doctor about how long you should wait to resume unprotected sexual activity or try for a pregnancy. Current recommendations range from 6 months to 2 years after treatment is completed, and your doctor will be able to consider your circumstances and give you more specific information about how long you should wait.

How surgery can affect male fertility

Surgery offers the greatest chance of cure for many types of cancer, especially those that have not spread to other parts of the body. But surgery on certain parts of the reproductive system can cause infertility.

Surgery for testicular cancer

The surgical removal of a testicle is called an orchiectomy. This is a common treatment for testicular cancer. As long as a man has one healthy testicle, he can continue to make sperm after surgery. (Less than 5% of males develop cancer in both testicles). But some with testicular cancer have poor fertility because the remaining testicle is not truly normal. For this reason, sperm banking before the testicle is removed is now recommended for those interested in saving their fertility .

Testicle removal (both testicles) for prostate cancer

Some with prostate cancer that has spread beyond the nearby area may have both testicles removed to stop testosterone production and slow the growth of prostate cancer cells. This surgery is called a bilateral orchiectomy. These males cannot father children unless they banked sperm before surgery.

Surgery to remove the prostate (radical prostatectomy)

For prostate cancer that has not spread beyond the gland, surgery to remove the prostate gland and seminal vesicles is one of the treatment options. The prostate and seminal vesicles together produce semen. The prostate is usually removed by one of two approaches. A robotic radical prostatectomy is performed using a robot to operate through several very small openings in the abdomen. Surgery removes the prostate gland and leaves males with no semen production and no ejaculation of sperm after the surgery. With sexual stimulation, males can still have orgasm, but no fluid comes out of the penis. Prostate surgery also can damage the nerves that allow a man to get an erection, This means he might not be able to get an erection sufficient for sexual intercourse.

Even if a patient can get an erection, if there’s no semen coming from the penis during orgasm, he cannot conceive a child during sex. The testicles still make sperm, but the tubes (vas deferens) that deliver sperm from the scrotum to the urethra are cut and tied off during removal of the prostate gland. This blocks the path of sperm. However, even after removing the prostate gland, there still are ways to get sperm from the testicle.

Surgery to remove the bladder (radical cystectomy)

Surgery to treat some bladder cancers is much like a radical prostatectomy, except the bladder is also removed along with the prostate and seminal vesicles. This procedure is called radical cystectomy.

Because this surgery removes the bladder and prostate gland, there is no semen production and no ejaculation of sperm after the surgery. With sexual stimulation, males can still have orgasm, but no fluid comes out of the penis.

Surgery to remove the bladder also can damage the nerves that allow a man to get an erection, causing erectile dysfunction (ED). This means he cannot get an erection sufficient for sexual penetration.

Even if you can get an erection, if there’s no semen coming from the penis during orgasm, you cannot conceive a child during sex. The testicles still make sperm, but the upper urinary tube for sperm (vas deferens) are cut and tied off during removal of the bladder and prostate gland. This blocks the path of sperm. However, even after removal of the bladder and prostate gland, there are ways to remove sperm from the testicle or its sperm storage area and use them to fertilize eggs.

Surgery that interferes with ejaculation

A few types of cancer surgery can damage nerves that are needed to ejaculate semen. They include removing lymph nodes in the belly (abdomen), which may be part of the surgery for testicular cancer and some colorectal cancers. Nerves are often damaged when lymph nodes are removed, and this can cause problems ejaculating. Sometimes surgery can permanently damage the nerves to the prostate and seminal vesicles that normally cause these organs to squeeze and relax to move the semen out of the body.

When these operations affect the nerves, a man still makes semen, but it doesn’t come out of the penis when he has an orgasm (climax). Instead it can flow backward into his bladder (called retrograde ejaculation) or goes nowhere.

In cases of retrograde ejaculation, medicines can sometimes restore normal ejaculation of semen. At orgasm, the internal valve at the bladder entrance closes, the prostate contracts and semen is ejaculated from the penis at orgasm. In the United States, pseudoephedrine sulfate (Sudafed) is the most common medicine used to restore normal ejaculation. Because it does not help everyone and may only work for a few doses, pseudoephedrine sulfate is usually taken only for the fertile week of the woman’s cycle.

Fertility specialists can sometimes gather sperm from these males using several types of treatments including electrical stimulation of ejaculation.

What can men do to preserve fertility before cancer treatment?

Men also can take steps to preserve their fertility before undergoing cancer treatment. For example 3:

- Sperm cryopreservation. This procedure involves freezing and storing sperm at a fertility clinic or sperm bank for use at a later date. Samples are frozen and can be stored for years.

- Radiation shielding. In this procedure, small lead shields are placed over the testicles to reduce the amount of radiation exposure they receive.

Radiation shielding

Radiation treatment can cause infertility through the permanent destruction of the sperm stem cells in the testicle. Testicular tissue damage is unavoidable if both testicles need to be directly radiated. When the radiation is directed at other structures in the pelvic area, the x-rays can often scatter and thus result in indirect testicular injury. Fertility may sometimes be preserved in these males by covering the testicles with a lead shield. If radiation is aimed at one testicle (as for some testicular cancers), the other testicle should be shielded if possible. Some boys with leukemia need radiation directly to both testicles to destroy the cancer cells. Shielding is not possible for these patients.

If you are getting radiation near your testicles, there is often a risk of damaging the sperm due to x-ray scatter. Doctors often advise men to avoid unprotected intercourse and efforts to achieve a pregnancy for 6 months after completion of radiation treatment.

Patients receiving radiation therapy should talk with their cancer team about the risks of infertility with the radiation treatment and the length of time they will need to avoid unprotected sexual activity afterward. For these reasons, patients should consider sperm banking to avoid the waiting period and also to possibly raise the odds of successful conception later on.

Options for men who are not fertile after cancer treatment

Use of donor sperm

Using donor sperm (also called donor insemination) is an inexpensive and simple way for men who are infertile after cancer treatment to become a parent. Major sperm banks in the United States collect sperm from young men who go through a detailed screening of their physical health, family health history, educational and emotional history, and even some genetic testing. Donors are also tested for sexually transmitted diseases, including HIV (the virus that causes AIDS) and the hepatitis B and C viruses. Couples may be able to choose a donor who will remain anonymous, one who provides personal information but does not want to make his identity known, or one who is willing to have contact with the child later in life.

Intrauterine insemination (IUI) with donor sperm is done by an obstetrician/gynecologist doctor in his or her office. The donor sperm are placed into the female partner’s uterus at the time of ovulation using a small flexible tube called a catheter. If needed, the woman’s doctor might prescribe hormones to cause more than one egg to mature and be released, which will increase the chances of fertilization and a pregnancy. As mentioned above, pregnancy rates for intrauterine insemination (IUI) typically range from 5%-15% per attempt when the female partner is healthy. Couples will commonly try the intrauterine insemination (IUI) approach up to 3 to 4 times.

The cost of donor sperm varies, but averages about $700 a sample, which does not include the cost of the insemination or the cost of hormones when they are used for the female. Be sure to ask for a list of all fees and charges, since these differ from one center to another.

Adoption

Adoption is usually an option for anyone who wants to become a parent. Adoption can take place within your own country through a public agency or by a private arrangement, or internationally through private agencies. Foster care systems specialize in placing children with special needs, older children, or siblings.

Most adoption agencies or foster care systems state that they do not rule out cancer survivors as potential parents. But they often require a letter from your doctor stating that you are cancer-free and can expect a healthy lifespan and a good quality of life. Some agencies or countries require a period of being off treatment and cancer-free before a cancer survivor can apply for adoption. Five years seems to be an average length of time. Unfortunately, only a handful of countries allow cancer survivors to adopt internationally.

There’s a lot of paperwork to complete during the adoption process, and at times it can seem overwhelming. Many couples find it helpful to attend adoption or parenting classes before adopting. These classes can help you understand the adoption process and give you a chance to meet other couples in similar situations. The process takes different lengths of time depending on the type of adoption you choose.

Costs of adopting vary greatly, from less than $4,000 (for a public agency, foster care, or special needs adoption) up to $50,000 (for some international adoptions, including travel costs).

You may be able to find an agency that has experience working with cancer survivors. Some discrimination clearly does occur both in domestic and international adoption. Yet, most cancer survivors who want to adopt can do so. Cancer survivors have legal protections (including against discrimination during adoption proceedings) under the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA).

Child-free living

Many couples, with or without cancer, decide they prefer not to have children. Child-free living allows a couple to pursue other life goals, such as career, travel, or volunteering in ways that help others. If you are unsure about having children, talk with your spouse or partner. If you are having trouble agreeing on the future, talking with a mental health professional may help you both think more clearly about the issues and make the best decision.

What can parents do to preserve the fertility of a child who has cancer?

Fertility should be discussed with children treated for cancer as soon as they are old enough to understand. Your consent and your child’s might be required before a procedure can be done.

If your child has begun puberty, options might include oocyte or sperm cryopreservation.

Girls who have cancer treatment before puberty can opt for ovarian tissue cryopreservation. During this procedure, ovarian tissue is surgically removed, frozen and later thawed and reimplanted.

One method being researched to preserve fertility in boys who have cancer treatment before puberty is a procedure in which testicular tissue is surgically removed and frozen.

Can cancer treatment increase the risk of health problems in children conceived afterward?

As long as you don’t expose your baby to cancer treatments in utero, cancer treatments don’t appear to increase the risk of congenital disorders or other health problems for future children.

However, if you receive a cancer treatment that affects the functioning of your heart or lungs or if you receive radiation in your pelvic area, talk to a specialist before becoming pregnant to prepare for possible pregnancy complications.

Egg freezing

Egg freezing also called oocyte cryopreservation, is an established method of trying to preserve fertility in women so you can attempt a pregnancy with in-vitro fertilization (IVF) treatment in future. Biologically, eggs can be stored indefinitely. You must let the clinic know if you change address so that they can contact you if the storage time limit is approaching. Egg freezing (oocyte cryopreservation) may be a good choice for women who do not have a partner. It also gives women in a relationship more complete control over the future use of frozen genetic material. For now, most fertility storage centers and courts give a man control over embryos created with his sperm, so if a breakup or divorce happens, a woman may not be able to use the embryos for a pregnancy.

There are two reasons why women may choose to freeze their eggs. The first is for health reasons; in particular, for women who wish to preserve their fertility before undergoing cancer treatment. The second is for personal and social reasons as many women may not be ready to have a child during their most fertile years.

You may consider freezing your eggs because you are:

- facing medical treatment that may affect your fertility, such as some forms of cancer treatment

- concerned about your fertility declining as you get older and feel you are not currently in a position to have a child

- at risk of premature menopause or suffer from endometriosis which involves the ovaries.

For egg freezing, mature eggs are removed and frozen before being fertilized with sperm. This process might also be called egg banking. When the woman is ready to become pregnant, the eggs can then be thawed, fertilized, and implanted in her uterus.

The steps involved

- Step 1. Before you agree to the freezing and storage of your eggs, your doctor will explain the process involved, including the risks and chance of success. Your clinic should also offer you the opportunity to discuss your feelings and any concerns you may have with a specialist counsellor.

- Step 2. You will be screened for infectious diseases, including HIV and Hepatitis B and C.

- Step 3. You will have a course of fertility drugs (usually daily injections for 8-14 days) and the development of follicles (fluid filled sacs containing eggs) will be monitored with ultrasound examinations and blood tests.

- Step 4. When the eggs are mature they will be retrieved in an ultrasound guided procedure under light anaesthetic. This is usually done in a hospital and requires you to be there for about four hours.

- Step 5. The eggs are then frozen and stored in liquid nitrogen.

When you are ready to attempt a pregnancy, your eggs are thawed and then fertilized with your partner’s or a donor’s sperm. If healthy embryos develop, one is transferred to the uterus and any remaining embryos can be frozen for later use.

Collecting the eggs typically takes 10 to 14 days, depending on where a woman is in her menstrual cycle. During the process, a woman takes injectable hormone medications for, on average, 8 to14 days, to allow several eggs to develop in the ovaries at once (often about 12 eggs in a woman under age 35). She comes in for monitoring ultrasounds to measure the follicles, where the eggs develop, about 3 to 5 times during the process. The eggs are then collected during outpatient surgery, usually with a light anesthetic (drugs given to make you sleepy while it’s done). An ultrasound is used to guide a needle through the upper part of the vagina and into the ovary to collect the eggs.

Some women might not be able to follow the schedule of hormone shots described. This could include women who have fast-growing cancers (who cannot delay cancer treatment). A concern has been that women with breast cancer or other estrogen-dependent tumors could increase tumor growth because of the high levels of estrogen caused by the hormone shots. However, research has not shown any increase in cancer recurrence in women with breast cancer who go through a hormone cycle to freeze eggs or embryos, and recent recommendations suggest good evidence that it is safe.

Traditionally, egg freezing has been more difficult than freezing embryos. This is because the egg is the largest cell in the human body and has a lot of water so ice crystals can form and damage the egg. However, a new method of freezing called vitrification has made egg freezing more efficient and successful. The methods and success rates of egg freezing have greatly improved in the past several years and it’s no longer considered experimental. Many fertility centers now report success rates much the same as using unfrozen eggs.

Another option for women undergoing fertility preservation, especially if a large number of eggs are retrieved, is to freeze half the eggs and fertilize the other half with sperm from a partner or donor and then freeze embryos. The benefit of this is that freezing embryos is still more efficient than freezing eggs but it allows a woman more flexibility if her relationship status changes or if she wants to avoid having excess frozen embryos.

If you are looking at egg freezing, ask how many live births the facility has had using frozen eggs. You might also want to ask how many eggs is recommended, on average, to produce a single live birth. This will depend largely on your age. You will want to know the cost of the procedure (including all the medicines), annual storage costs of the frozen eggs, and the estimated costs of fertilizing and implanting later. Egg freezing usually costs slightly less than embryo freezing.

An important note about freezing

If you have frozen eggs, embryos, or ovarian tissue, it’s important to stay in contact with the cryopreservation facility to be sure that any yearly storage fees are paid and your address is updated.

Important questions to ask your doctor

A study of fertility clinics in the US found that the information about egg freezing available on their websites was inadequate. It is important that you are well-informed about all aspects of egg freezing before you decide to proceed. Here are some questions you may wish to ask your doctor:

- Does this clinic use the vitrification method to freeze eggs?

- What is the clinic’s success rate for egg freezing?

- How many eggs have been thawed at this clinic and how many live births have resulted from these thawed eggs?

- What is my chance of having a baby from frozen eggs, considering my personal circumstances such as my age and estimated ovarian reserve (a measure of how many eggs you are likely to produce)?

- How many eggs should I store to have a reasonable chance of having a baby? (Remember that you might require more than one stimulated cycle to retrieve enough eggs to give you an acceptable chance of success further down the track)

- What is the approximate total cost, bearing in mind that I may need more than one stimulation and egg retrieval procedure to yield enough eggs?

Egg freezing success rates

Successful pregnancy rates vary from center to center. Centers with the most experience usually have better success rates and costs vary, too. The method for freezing eggs varies between clinics but studies show that the most effective method for freezing eggs is a rapid method called ‘vitrification’.

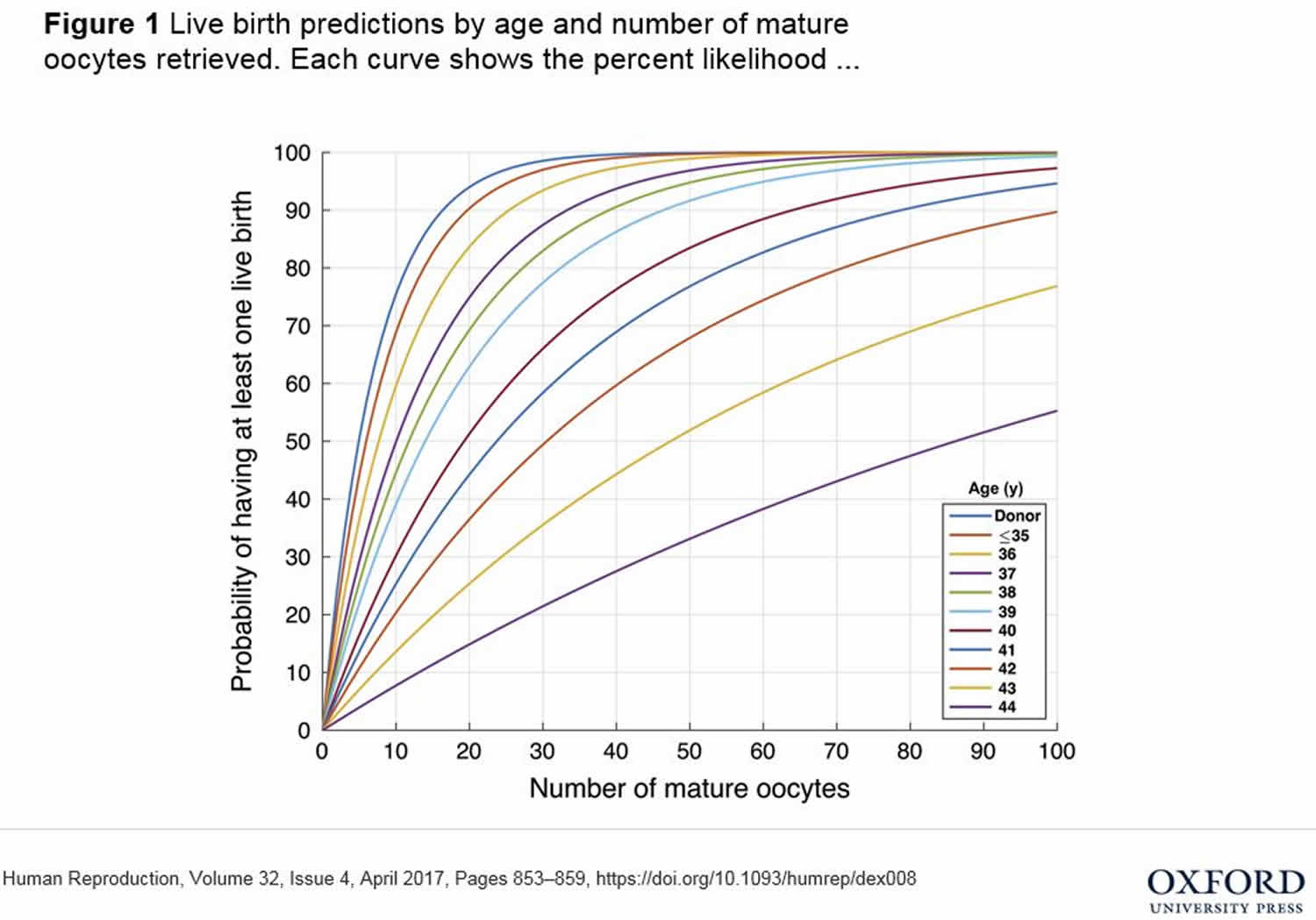

The chance of a live birth from frozen ‘vitrified’ eggs is similar to the chance from ‘fresh’ eggs which are usually used in IVF treatment. The two most important factors that determine the chance of having a baby from frozen eggs are your age when your eggs are frozen and the number of eggs that are stored.

The number and quality of the eggs that develop when the ovaries are stimulated decline with increasing age. A woman in her early thirties might have 15-20 eggs available for freezing after the hormone stimulation, but for women in their late thirties and early forties the number is usually much lower. Also, as women age they are more likely to have eggs with chromosomal abnormalities.

The number of eggs available for freezing and their quality is important because in every step there is a risk that some are lost. Of the eggs that are retrieved, some may not be suitable for freezing, some may not survive the freezing and thawing processes, and some may not fertilise or develop into normal embryos. Of the embryos that are transferred, only some will result in a pregnancy, and some pregnancies miscarry.

The following graph, published in the journal Human Reproduction in 2017, estimates the probability of a live birth according to how many mature eggs a woman freezes at various ages. The graph shows that a woman who freezes 10 eggs at the age of 44 has about an 8 per cent chance of having a baby, whereas a woman who freezes 10 eggs under the age of 35 has about a 70 per cent chance.

Figure 1. Egg freezing success rates by age

Risks associated with egg freezing

A small proportion of women have an excessive response to the fertility drugs that are used to stimulate the ovaries. In rare cases this causes ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS), a potentially serious condition. Bleeding and infection are very rare complications of the egg retrieval procedure.

Egg freezing is still a relatively new technique and the long-term health of babies born as a result is not known. However, it is reassuring that their health at birth appears to be similar to that of other children.

The other risk to consider is that egg freezing does not guarantee you will have a baby. In the UK, the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority says only 18 per cent of women who use their own thawed eggs in IVF treatment currently end up having a baby.

Freezing of eggs for fertility cost

The cost of egg freezing varies between clinics. In most cases there is only a Medicare rebate provided for egg freezing for medical reasons, which means that women who choose to freeze their eggs for other reasons may have considerable out-of-pocket expenses.

Clinics usually charge for:

- management of the hormone stimulation of your ovaries (devising a plan for your treatment and prescribing medication)

- the drugs used to stimulate the ovaries

- the egg collection procedure which may include admission to a private hospital and fees for an anesthetist

- freezing and storage of the eggs.

Medicare does not cover the storage of frozen eggs, regardless of whether they are stored for medical or other reasons. This may cost hundreds of dollars for each year your eggs are stored. There will also be costs involved when you decide to use the eggs to try to conceive. The process of thawing the eggs, fertilizing them with sperm, and growing embryos for transfer into the uterus can cost thousands of dollars in out-of-pocket expenses not covered by Medicare.

Embryo freezing

Embryo freezing also called embryo cryopreservation, is the most established and successful method of preserving a woman’s fertility today. Mature eggs are removed from a woman’s ovaries and fertilized in the lab. This is called in vitro fertilization (IVF). Sometimes thousands of sperm are put in a sterile dish with each egg. Sometimes one sperm is injected into each egg using a special lab equipment under a microscope. The embryos are then frozen to be used after cancer treatment.

Embryo freezing (embryo cryopreservation) works well for women who already have a partner, though single women can still freeze embryos using donor sperm.

The process of collecting eggs for embryo freezing is the same as for egg freezing (see above). Eggs are collected during outpatient surgery, usually with a light anesthetic (drugs are given to make you sleepy while it’s done). An ultrasound is used to see the ovaries and the fluid sacs (follicles) that contain ripe eggs. A needle is guided through the upper vagina, into each follicle to collect the eggs. The eggs are inseminated with sperm and the embryos that develop are then frozen and stored.

A woman will have a better chance of a successful pregnancy if several embryos are stored. A woman’s age will play a large role in the chances of pregnancy, with a younger age at the time of egg retrieval resulting in higher pregnancy rates. The quality of the embryos also makes a difference, however. Some labs freeze embryos when they are only 2 cells. When they are thawed, these embryos are nourished while they develop further. Once embryos have had 5 days to grow they reach the blastocyst stage. Some embryos do not make it that far. Blastocysts are much more likely to implant and begin a pregnancy than are 2-cell embryos. Some labs let the embryos develop into blastocysts before freezing them. An advantage of using blastocysts in a replacement cycle is that only one, or at most 2 can be placed in the woman’s uterus. For women under age 35, a single embryo transfer is the safest way of using IVF to get pregnant to avoid multiple pregnancy. Although many couples say they would like to have twins, a twin pregnancy is much higher risk to the babies and mother, and should be avoided as much as possible.

An important note about freezing

If you have frozen eggs, embryos, or ovarian tissue, it’s important to stay in contact with the cryopreservation facility to be sure that any yearly storage fees are paid and your address is updated.

Embryo freezing success rates

Successful pregnancy rates vary from center to center. Centers with the most experience usually have better success rates and costs vary, too.

Sperm freezing and storage

Sperm freezing and storage also known as sperm banking, is the procedure whereby sperm cells are frozen to preserve them for future use. Scientists freeze the sperm using a special media then keep sperm in liquid nitrogen at minus 320.8 °F (-196 °C), and it can be stored for many years while maintaining a reasonable quality.

Sperm banking is the most well established method of fertility preservation for men. It’s a fairly easy and successful way for men who have entered adolescence to store sperm for future use. It’s usually offered before cancer treatment, to males who might want to have children in the future but sometimes doctors might not mention this option. If you know you might want to father a baby later, ask about it. Your doctor can refer you to a reproductive urologist for sperm banking, or the cancer doctor might arrange it himself or herself. You might be able to find a sperm bank yourself with an online search.

Many males with cancer will have semen samples showing that the ejaculate volume, sperm count, sperm motility, or percentage of sperm with normal shape is low. This is a very common finding in males with cancer. It is important for patients to know that they can and should store the sperm even if they have reduced sperm quality or quantity. The only requirement is that the sperm be alive. Boys as young as 12 or 13 years old will often be able to successfully bank sperm. If they have started puberty, there is a good chance that they are making sperm and can produce a semen sample for freezing.

In sperm banking, a male provides one or more samples of his semen, ideally by ejaculating. Semen collection is usually done by masturbation in a private room at a sperm bank facility or hospital, although sometimes arrangements can be made for the patient to bring a sample that he collected at home into the lab.

The sperm needs to be received in the lab within one hour after ejaculation. The man ejaculates (has a sexual climax with the release of semen from the urethral opening at the tip of his penis) through masturbation or with the help of stimulation from a partner. The semen is collected in a sterile cup. Sperm is not usually collected during intercourse because it could be contaminated with bacteria and vaginal fluid. For men with strong religious rules against masturbation, some banks facilitate semen collection during intercourse using a special silicone collection condom.

A vibratory stimulation device (“vibrator”) can be used to help to a man ejaculate if he is having difficulty. Difficulty reaching climax and ejaculation can occur in a patient who is not comfortable with masturbation, in males with a lot of stress or anxiety, in males on certain medications such as narcotic pain medications or antidepressants, and in males with certain physical or anatomical changes to the penis prevent normal sexual stimulation.

If you live far from any lab or sperm bank, you might be able to use a mail-in kit. Some sperm banks provide these kits to patients. The man collects his sample at home, mixes it with a special protective chemical, and express mails it to the sperm bank right away. Some sperm may die with this increased time requirement, so if you can collect a sample and immediately deliver it to a lab, it is a better option.

Once the sperm bank gets the sample, they test it to see how many sperm cells it contains (this is the sperm count), what percentage of the sperm are able to swim (which is called motility), and what percentage have a normal shape (called morphology). The sperm cells are then frozen and stored.

Sperm banking is an option for males who might want to have children after completing cancer treatment, even if they aren’t sure that they will one day want to father a child. By storing sperm, male cancer patients can decide this issue later and leave their options open. If the samples are not used, they can be discarded or donated for research.

Other ways to collect sperm

From the urine (for males with retrograde ejaculation)

Sometimes the nerves that are needed to ejaculate semen or close the valve at the entrance to the bladder are damaged during cancer surgery or radiation treatment. When this happens, the male might still make semen, but it might not come out of his penis at orgasm. Instead, it might flow backward into his bladder (called retrograde ejaculation). This is not painful or harmful, though the urine may look cloudy afterward because there’s semen in it.

Fertility specialists are often able to collect sperm from the urine of these males and use these sperm to help achieve a pregnancy. These sperm can sometimes be placed into the female partner’s uterus at the time of ovulation using a small flexible tube called a catheter.

Electroejaculation

Ejaculation is a complex process that is necessary for the release of sperm from the body. Some males will be unable to ejaculate due to stress, anxiety, or other psychological causes. This situation is common in males newly diagnosed with cancer who are trying to bank sperm. Additionally, some young adolescent males who may have had no prior experience with masturbation might not be able to produce a semen sample. For these patients, electroejaculation can be used to successfully stimulate the pelvic nerves that cause contraction of the epididymis, vas deferens, prostate gland, seminal vesicles, and pelvic muscles that cause the release of sperm. The electroejaculation procedure is done with the patient asleep under an anesthetic.

Several other conditions can also cause an inability to ejaculate. First, men with a history of injury to the belly (abdominal) nerves or pelvic nerves can lose the ability to ejaculate. These nerve injuries occur most commonly after surgery or radiation therapy in the belly (abdominal) or pelvic areas. The inability to ejaculate can also occur in men on certain medications, such as narcotic pain relievers and antidepressants. These medicines are used in many patients with cancer and can negatively affect fertility preservation efforts. Finally, some men will have swelling, inflammation, or other changes in the anatomy of the penis or pelvic tissue that will interfere with the penile stimulation that is needed to cause ejaculation.

Small numbers of infertility clinics have the equipment necessary to perform electroejaculation.. A probe is put into the rectum and a low voltage electrical current is used to stimulate ejaculation. The semen that is collected by electroejaculation can either be used immediately or cryopreserved for future use. Either way, two options exist for ultimate use of the sperm. It can be used in IUI (where the sperm is delivered into the uterus through a catheter at the time of ovulation) or IVF (where mature eggs are removed from a woman’s ovaries and joined with the sperm in the lab to create embryos, which are then transferred into the female partner’s uterus).

Sperm extraction and aspiration procedures

These procedures are options for collecting sperm from men who do not have sperm in their semen, either before or after cancer treatments. Both require minor surgery performed by a urologist.

- In percutaneous epididymal sperm aspiration (PESA), a needle is inserted through the scrotal skin and into the epididymis (the coiled tubes that sit on top of the testicle). Suction is applied to the needle, and sperm are aspirated out through the needle.

- In a microsurgical epididymal sperm aspiration (MESA) procedure, a small incision is made in the scrotal skin, and an operating microscope is used to remove sperm from the epididymis under microscopic vision. Sperm extraction from the epididymis is typically only performed when sperm production is normal and a blockage exists within the sperm delivery system.

- In testicular sperm extraction (TESE), a small incision is made in the scrotal skin, and tiny pieces of testicular tissue are removed inspected for sperm cells.

- A micro-TESE procedure is similar, except an operating microscope is used to inspect and help select the areas of testicular tissue that are removed.

Testicular sperm extraction (TESE) and Micro-TESE procedures are commonly done on men with either normal or decreased sperm production. This contrasts with sperm extraction from the epididymis, which is typically only performed when sperm production is normal but the sperm delivery system is blocked.

With both epididymal and testicular sperm extraction techniques, if mature sperm are found, they can be used right away for in vitro fertilization with intracytoplasmic sperm injection (IVF-ICSI) or frozen for future use.

An important note about freezing sperm

It’s important to stay in contact with the sperm bank so that yearly storage fees are paid and your address is updated. Once a couple is ready to have a child, the frozen sperm is sent to their fertility specialist. Some sperm banks will destroy and discard sperm samples when patients lose touch with them.

Using sperm for intrauterine insemination (IUI)

If the thawed sperm sample contains at least 5-10 million motile (actively swimming) sperm, it can potentially be used for IUI. The thawed sperm are washed and concentrated, and then they are place in a sterile solution called media. When the woman is at her most fertile time of the month, this fluid is introduced into her uterus by inserting a tiny tube called a catheter through her vagina, into the small opening in her cervix, and up into the uterus.

This procedure usually just takes a few minutes and is performed in an obstetrician/gynecologist doctor’s office. Sometimes the woman takes hormones to mature more than 1 egg before the sperm is placed in her uterus to increase the chance of pregnancy. This is called superovulation.

Using sperm for in vitro fertilization (IVF) and in vitro fertilization with intracytoplasmic sperm injection (IVF-ICSI)

With IVF, after eggs are retrieved from the woman, each is cleaned and placed in a sterile dish with several thousand sperm. The goal is for one of the sperm to then fertilize the egg. This often works well when the sperm cells have good motility (swimming power). After freezing and thawing, however, motility can sometimes be low. Currently, it is more common to inject a sperm into each egg, getting around that problem and increasing the odds of successful fertilization. This procedure is called IVF-ICSI, which stands for in vitro fertilization with intracytoplasmic sperm injection. Sometimes it’s just called ICSI. With ICSI, a single viable sperm is injected directly into an egg to fertilize it, resulting in an embryo that can then be transferred back into the female partner’s uterus to achieve a pregnancy.