Frontal lobe syndrome

Frontal lobe syndrome is a broad term used to describe the damage of higher functioning processes of the brain such as motivation, planning, social behavior, and language/speech production 1. Although the cause may range from trauma to neurodegenerative disease, regardless of the cause, frontal lobe syndrome poses a difficult and complicated condition for physicians. Classically considered unique among humans, the frontal lobes are involved in a variety of higher functioning processing, such as regulating emotions, social interactions, and personality. The frontal lobes are critical for more difficult decisions and interactions that are essential for human behavior. However, with the spread of neurosurgery and procedures such as lobotomy and leucotomy for treatment of psychiatric disorders, a variety of cases have illustrated the significant behavioral and personality changes due to frontal lobe damage. Harlow first described this collection of symptoms as “frontal lobe syndrome” after his research on the famous Phineas Gage who suffered a dramatic change in behavior as a result of trauma. Thus, an abnormality in the frontal lobe could dramatically change not only processing but personality and goal-oriented directed behavior 1.

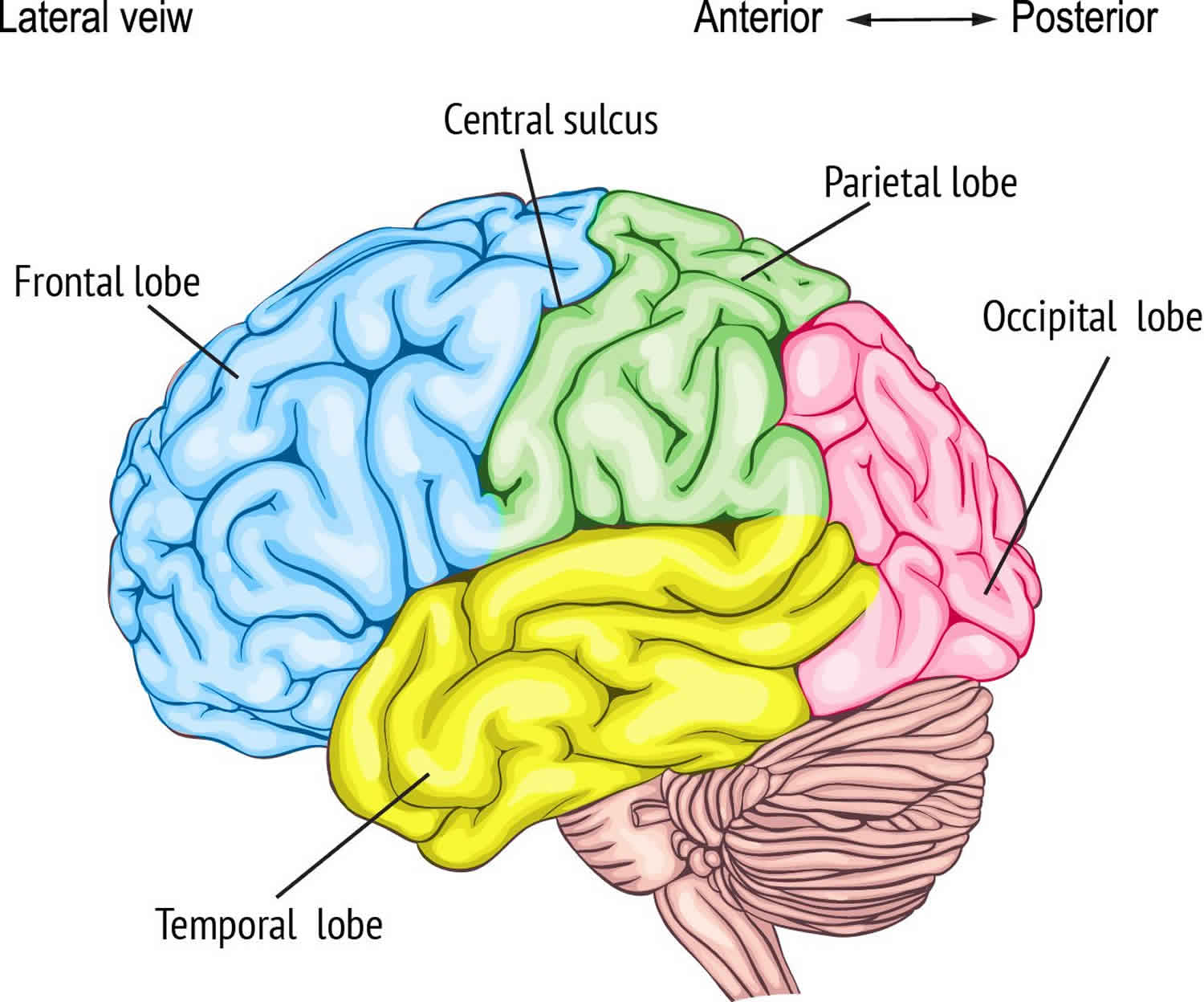

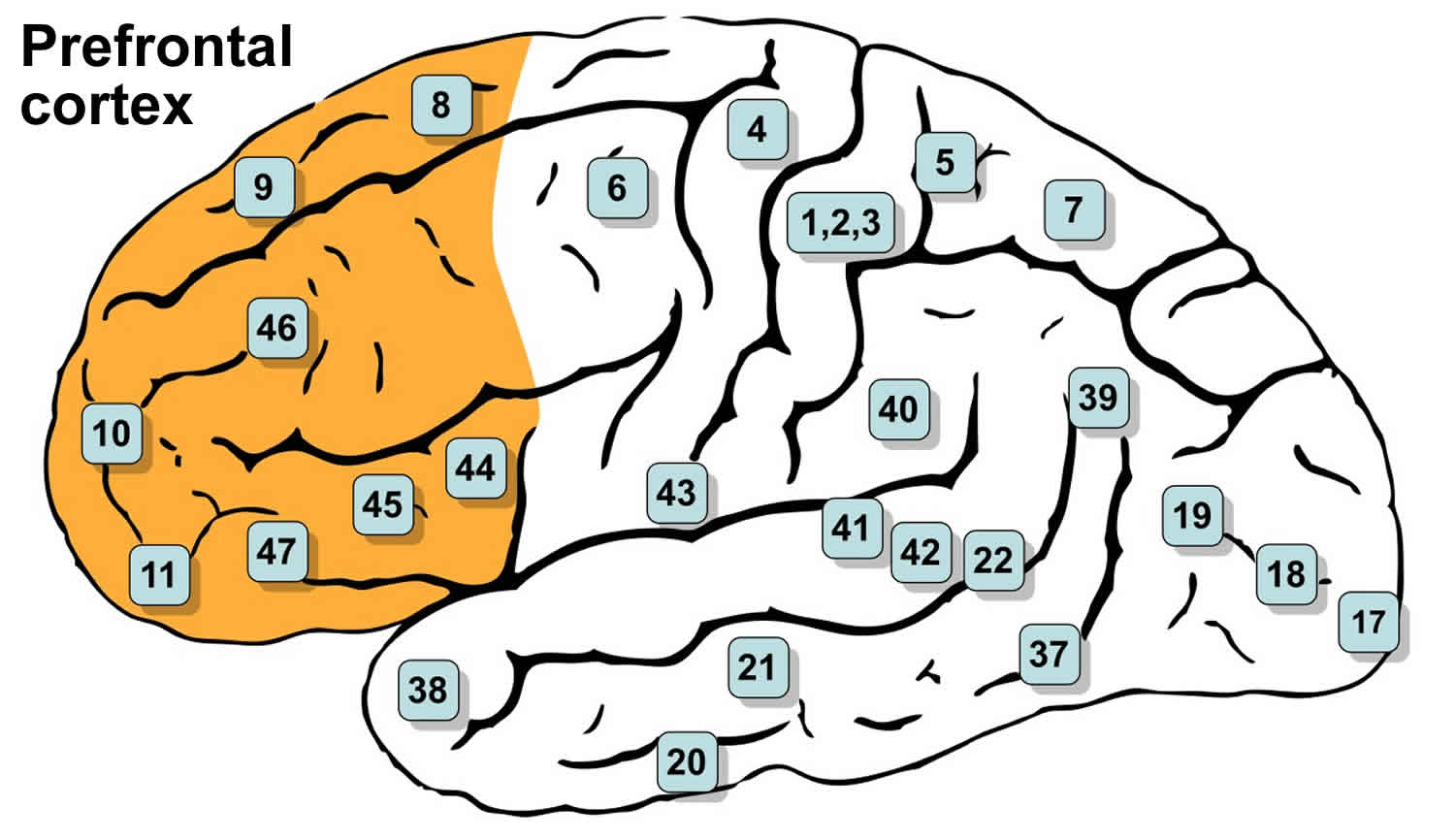

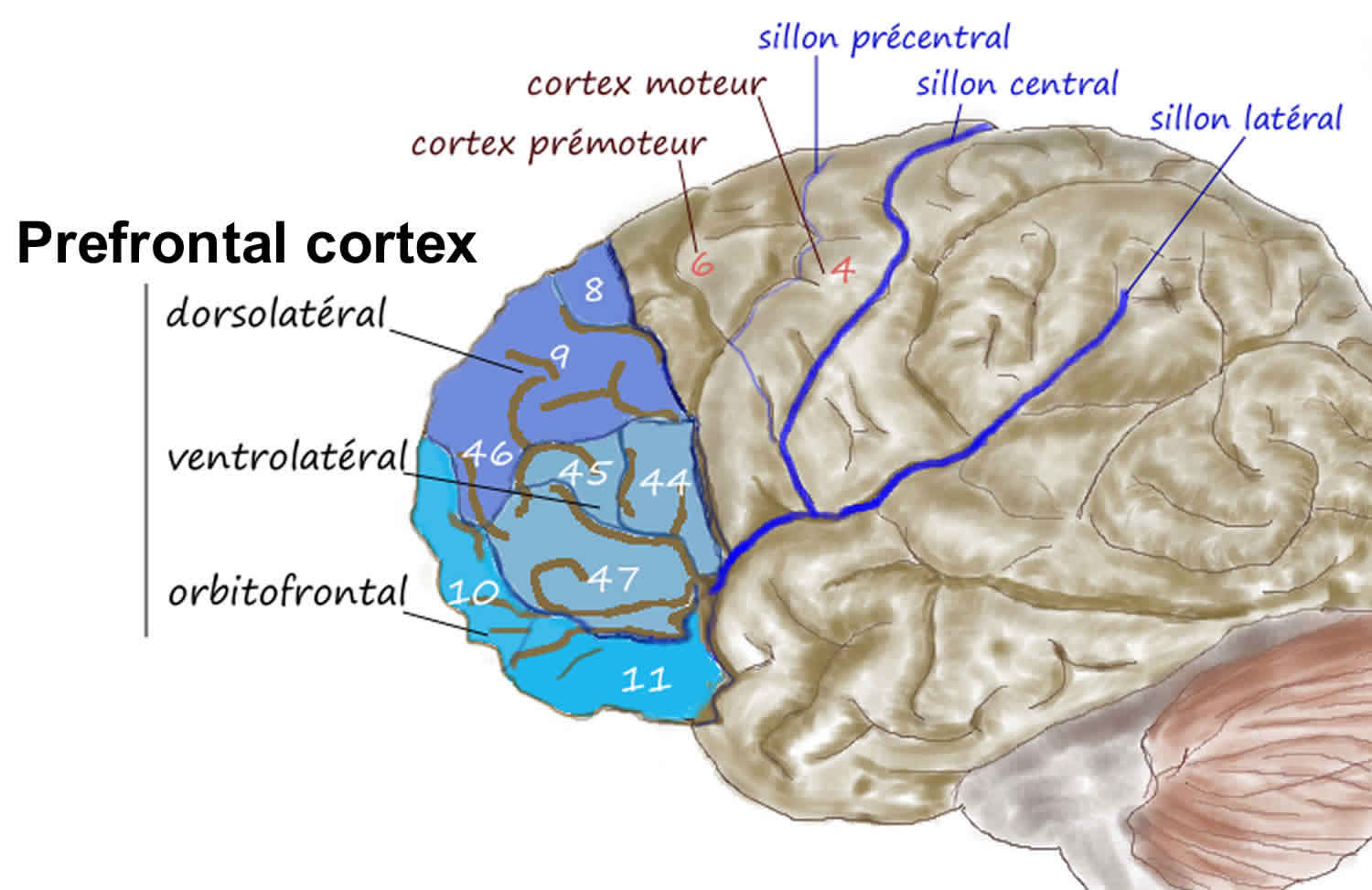

Neuroanatomically, the frontal lobe is the largest lobe of the brain lying in front of the central sulcus (directly behind the forehead). Frontal lobe is divided into 3 major areas defined by their anatomy and function. They are the primary motor cortex, the supplemental and premotor cortex, and the prefrontal cortex. The prefrontal cortex contains the Brodmann areas 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 24, 25, 32, 44, 45, 46, and 47 (see Figure 2). Damage to the primary motor, supplemental motor, and premotor areas lead to weakness and impaired execution of motor tasks of the contralateral side. The inferolateral areas of the dominant hemisphere are the expressive language area (Broca area, Brodmann areas 44 and 45), to which damage will result in a non-fluent expressive type of aphasia. Frontal lobe syndrome, in general, refers to a clinical syndrome resulting from damage, and impaired function of the prefrontal cortex, which is a large association area of the frontal lobe (see Figure 2). The areas involved may include the anterior cingulate, the lateral prefrontal cortex, the orbitofrontal cortex, and the frontal poles.

Prior research has sought to identify the major areas where lesions may occur to cause the behavioral changes in frontal lobe disorders.

Ventromedial Orbitofrontal Cortex

Commonly known to cause “frontal lobe personality”, lesions in the orbitofrontal areas classically cause dramatic changes in behavior leading to impulsivity and a lack of judgment. Lesions are usually found in Broadmann’s areas 10, 11, 12, and 47 is associated with a loss of inhibition, emotional lability, and inability to function appropriately in social interactions. The most popular case involving a lesion in this area is the case of Phineas Gage who had major behavioral changes after his trauma. However, in a study by Tranel and Damasio et al., a variety of other etiologies such as stroke and neoplasms may cause “frontal lobe personality” 2.

Anterior Cingulate and Dorsolateral Syndromes

Lesions in the areas around Brodmann areas 9 and 46 may cause deficits within working memory, rule-learning, planning, attention, and motivation 3. Recent studies have reinforced that dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (Broadmann’s areas 8, 9, 10 and 46) is critical for working memory function and in particular for monitoring and manipulating the content of working memory. Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex may also affect attention as several cases have documented patients complaining of attentional deficits after brain trauma 4. There are also psychiatric implications due to injury to dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. Previous studies have researched how lesions in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex may cause “pseudo-depressive” syndrome associated with dorsolateral prefrontal cortex associated with a loss of initiative, decreased motivation, reduced verbal output, and behavioral slowness (abulia). Other processing issues include rule learning, task switching, planning/ problem solving, and novelty detection and exogenous attention 3. The anterior cingulate cortex is important for the motivation behind attention, but may also be involved in a variety of psychiatric disorders such as depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) 5.

A new area of research within the dorsolateral frontal cortices revolves around “intuition.” The frontal lobes can communicate with the limbic system and association cortex. In turn, this emotional influence associated with abstract decision to create more efficient or “intuitive” decision in a short span of time 6.

Figure 1. Frontal lobe

Figure 2. Prefrontal cortex (Brodmann areas 8, 9, 10, 11, 44, 45, 46 and 47)

Frontal lobe syndrome causes

The cause of frontal lobe syndrome includes an array of diseases ranging from closed head trauma (that may cause orbitofrontal cortex damage) to cerebrovascular disease, brain tumors compressing the frontal lobe, brain infections, mental retardation, and neurodegenerative disease 1. Other causes include epilepsy with frontal lobe foci, HIV, multiple sclerosis, normal pressure hydrocephalus and early onset dementia.

Frontal lobe syndrome due to neurodegenerative disorders is usually caused by 2 main histopathologies: alpha-synuclein and tau protein. Tauopathies that impair the frontal lobes include frontotemporal dementia, chronic traumatic encephalopathy, supranuclear palsy, corticobasal degeneration and advanced Alzheimer disease. If tau is hyperphosphorylated, the protein dissociates from microtubules and creates aggregates that are insoluble 7. The Braak stages classify the degree to which neurofibrillary tangles exist. In contrast, alpha-synuclein is associated with multiple system atrophy, Parkinson disease, and diffuse Lewy body dementia.

Frontal lobe syndrome symptoms

The most important element in testing patients with frontal lobe impairment is to perform a thorough neurologic exam. History should also be obtained from family and close contacts to get a “real idea” of how the patient lives. One of the seeming paradoxes of frontal lobe dysfunction is that informants may complain about the patient’s “inability to do anything,” yet on at least cursory mental status testing, the patient appears normal or only mildly impaired. This dissociation should be a clue that frontal lobe dysfunction may be present. Symptoms of possible frontal lobe dysfunction that should be probed include change in performance at work and changes organizing and executing difficult tasks such as holiday dinners or travel itineraries 8. The examiner should inquire about the following changes:

- Appropriateness of behavior: Does the patient say things that he or she would never have said before, such as “You are so fat” or “That is a really ugly dress”?

- Patient’s table manners: Does the patient now take food and start eating before everyone else, or take food from other people’s plates without asking?

- Patient’s empathy and ability to infer the mental state of others: This kind of dysfunction often leads to inappropriate behavior.

- Possible apathy: Does the patient care less about hobbies, family members, and finances than previously?

- An increase or decrease in the patient’s sexuality or in his or her judgment about possible liaisons.

In addition to these data, the examiner should obtain careful developmental, head trauma, and social histories, including educational and personal attainments. The examiner should also probe about possible substance abuse, whether the patient was a victim of past abuse (physical, sexual, or psychiatric) and about major psychiatric stressor (eg, deaths of friends or family, divorce or separation, job loss or financial reversals). Indeed, a detailed past psychiatric history is required.

During the exam, it is important to note for behavioral changes such as abulia (absence of willpower or an inability to act decisively), inappropriate jocularity (Witzelsucht), insight impairment, confabulation, utilization behavior and environmental dependency (i.e., patients putting on glasses that are not theirs), perseveration, persistence, spontaneous frontal release signs, and incontinence. A mental status exam should be completed to evaluate attention (digit span forward and backward, months forward and backward), memory, perseveration and set shifting ability (Luria alternating sequencing, Trails B, Wisconsin card sorting test), ability to suppress inappropriate response (auditory, visual go-no-go tasks, Stroop testing), word generation (FAS word generation), abstract reasoning, judgement, language, and testing for hemineglect. Other exams include olfaction, optokinetic nystagmus testing (with lesions contralateral to the decreased fast phase), hemiparesis or upper motor neuron signs, motor impersistence, gegenhalten (inability to relax muscles for testing of passive range of motion), primitive reflexes, frontal magnetic gait disturbance, and skull shape to suggest a frontal meningioma. However, during the exam, it is important to note if the patient was subject to past abuse, recent trauma or psychiatric stress.

Frontal lobe syndrome diagnosis

Before a diagnosis of a frontal lobe syndrome, it is important to rule out other causes that may cause cognitive impairment, for example, B12, thyroid function, and syphilis serology if applicable. In regards to imaging, MRI may be done to evaluate for atrophy, hematomas, vascular and microvascular pathology. Although not as specific or sensitive, CT may be done to rule out acute bleeds or hydrocephalus. If there is clinical suspicion for frontotemporal dementia (FTD), neurologists may consider a deoxyglucose PET scan showing decreased activity in the frontal lobe with sparing of the temporal-parietal areas 9.

Laboratory studies

- Choice of blood tests depends on clinical setting.

- In many cases, tests of thyroid function, vitamin B-12 level, and serology for syphilis are appropriate.

- In other instances, testing for HIV or connective tissue disorders is indicated.

Frontal lobe syndrome treatment

Treatment depends on the type of pathology present. For some types of dementia, such as Lewy body, acetylcholinesterase inhibitors have been proven beneficial. In contrast, acetylcholinesterase inhibitors in frontotemporal dementia have not been proven helpful 10. Nonmedical treatments include physical and occupational therapy, especially in diseases such as frontotemporal dementia. Speech therapy may also be helpful for symptoms like aphasia, apraxia, and dysarthria. Pimavanserin, a selective serotonin 5-HT2A inverse agonist, has been suggested as a new therapy for synuclein-associated psychosis 11. Furthermore, as executive functioning decline, it is imperative to provide general support at home such as a caretaker.

Frontal lobe syndrome prognosis

The prognosis of frontal lobe syndrome depends on the underlying cause. However, for neurodegenerative diseases, there is no cure.

- Pirau L, Lui F. Frontal Lobe Syndrome. [Updated 2018 Dec 19]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2019 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532981[↩][↩][↩]

- Damasio H, Grabowski T, Frank R, Galaburda AM, Damasio AR. The return of Phineas Gage: clues about the brain from the skull of a famous patient. Science. 1994 May 20;264(5162):1102-5.[↩]

- Szczepanski SM, Knight RT. Insights into human behavior from lesions to the prefrontal cortex. Neuron. 2014 Sep 03;83(5):1002-18.[↩][↩]

- Daffner KR, Mesulam MM, Holcomb PJ, Calvo V, Acar D, Chabrerie A, Kikinis R, Jolesz FA, Rentz DM, Scinto LF. Disruption of attention to novel events after frontal lobe injury in humans. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 2000 Jan;68(1):18-24.[↩]

- Yücel M, Wood SJ, Fornito A, Riffkin J, Velakoulis D, Pantelis C. Anterior cingulate dysfunction: implications for psychiatric disorders? J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2003 Sep;28(5):350-4.[↩]

- McCrea SM. Intuition, insight, and the right hemisphere: Emergence of higher sociocognitive functions. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2010;3:1-39.[↩]

- Guo T, Noble W, Hanger DP. Roles of tau protein in health and disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2017 May;133(5):665-704.[↩]

- Cruz-Oliver DM, Malmstrom TK, Allen CM, Tumosa N, Morley JE. The Veterans Affairs Saint Louis University Mental Status Exam (SLUMS Exam) and the Mini-Mental Status Exam as Predictors of Mortality and Institutionalization. J Nutr Health Aging. 2012. 16(7):636-41.[↩]

- Ismail Z, Nguyen MQ, Fischer CE, Schweizer TA, Mulsant BH. Neuroimaging of delusions in Alzheimer’s disease. Psychiatry Res. 2012 May 31;202(2):89-95.[↩]

- Kerchner GA, Tartaglia MC, Boxer A. Abhorring the vacuum: use of Alzheimer’s disease medications in frontotemporal dementia. Expert Rev Neurother. 2011 May;11(5):709-17.[↩]

- Cummings J, Isaacson S, Mills R, Williams H, Chi-Burris K, Corbett A, Dhall R, Ballard C. Pimavanserin for patients with Parkinson’s disease psychosis: a randomised, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2014 Feb 08;383(9916):533-40.[↩]