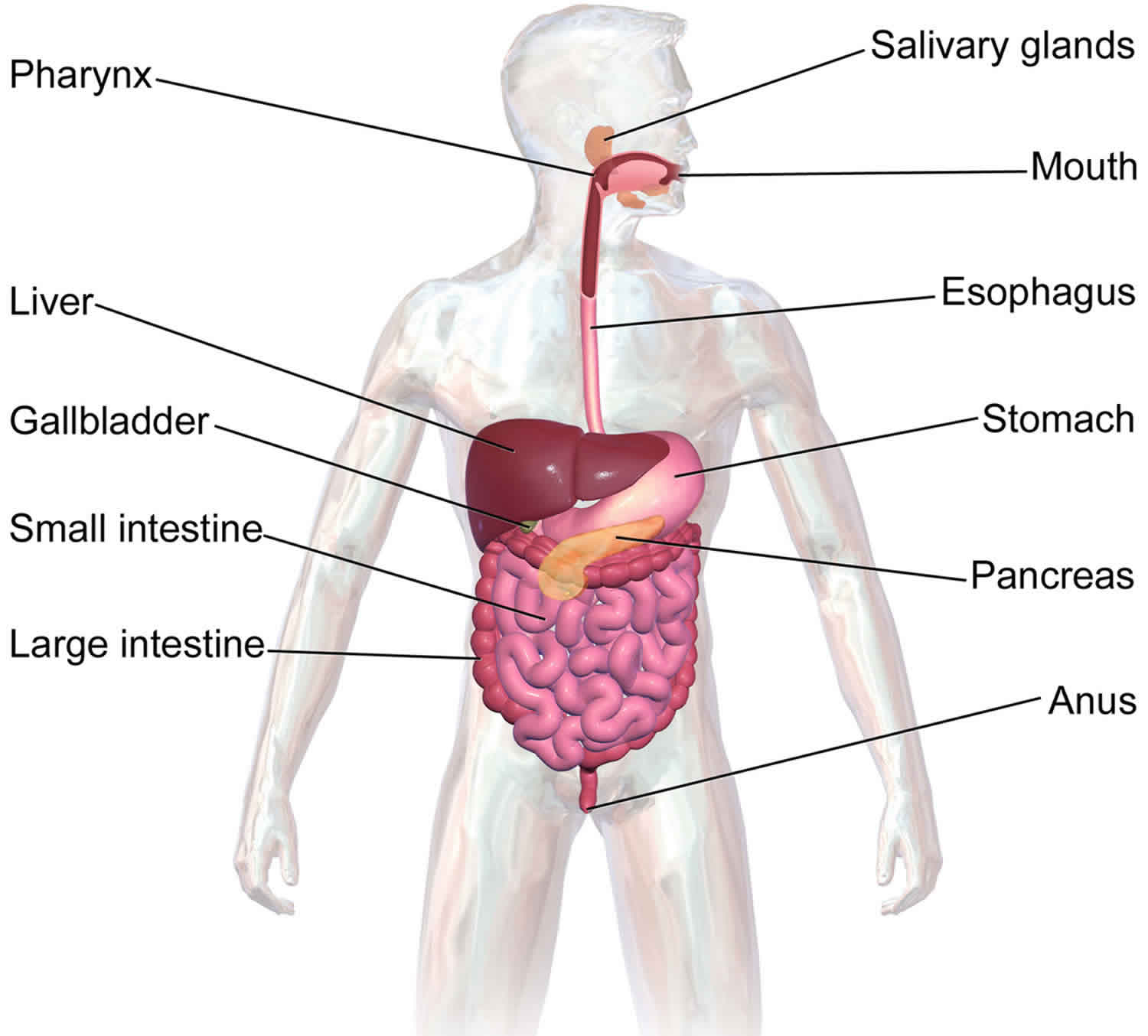

Gastrointestinal tract and system

Your gastrointestinal system breaks down the food you eat into nutrients such as carbohydrates, fats and proteins. They can then be absorbed into your bloodstream so your body can use them for energy, growth and repair. Unused materials are discarded as feces (or poop).

Your gastrointestinal system starts at your mouth, then your esophagus, stomach, small intestine, large intestine and anus. These organs are the specialized parts of a long, twisting tube called the gastrointestinal tract.

Other organs that form part of the gastrointestinal system are the pancreas, liver and gallbladder.

Each organ of the gastrointestinal system has an important role in digestion.

Mouth

When you eat, your teeth chew food into very small pieces. Glands in your cheeks and under your tongue produce saliva that coats the food, making it easier to be chewed and swallowed.

Saliva also contains enzymes that start the digestion of the carbohydrates in your food.

Esophagus

Your esophagus is the muscular tube that carries food from your mouth to your stomach after you swallow. A ring of muscle at the end of the esophagus relaxes to let food into your stomach and contracts to prevent stomach contents from escaping back up the esophagus.

Stomach

Your stomach wall produces gastric juice (hydrochloric acid and enzymes) that digests proteins. The stomach acts like a concrete mixer, churning and mixing food with gastric juice to form chyme – a thick, soupy liquid.

Small intestine

Bile from your gall bladder and enzymes in digestive juices from your pancreas empty into the upper section of your small intestine. These help break down protein into amino acids and fat into fatty acids. These smaller particles, along with sugars, vitamins and minerals, are absorbed into the bloodstream through the wall of your small intestine.

It is called small because it is about 3.5cm in diameter but it is about 5m long to provide lots of area for absorption. Most of the chemical digestion of proteins, fats and carbohydrates is completed in your small intestine.

Large intestine and anus

The lining of your large intestine absorbs water, mineral salts and vitamins. Undigested fiber is mixed with mucus and bacteria – which partly break down the fiber – to nourish the cells of the large intestine wall and so help keep your large intestine healthy. Feces are formed and stored in the last part of the large intestine (the rectum) before being passed out of the body through the anus.

Gastrointestinal disease

Gastroesophageal reflux disease

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) occurs when stomach acid contents frequently flow back up into your esophagus (the tube connecting your mouth and stomach). This backwash (acid reflux) can irritate the lining of your esophagus. It causes a burning sensation in the chest or throat.

Many people experience acid reflux from time to time. Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is mild acid reflux that occurs at least twice a week, or moderate to severe acid reflux that occurs at least once a week.

Most people can manage the discomfort of GERD with lifestyle changes and over-the-counter medications. But some people with GERD may need stronger medications or surgery to ease symptoms.

Seek immediate medical care if you have chest pain, especially if you also have shortness of breath, or jaw or arm pain. These may be signs and symptoms of a heart attack.

Make an appointment with your doctor if you:

- Experience severe or frequent gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms

- Take over-the-counter medications for heartburn more than twice a week

Gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms

Common signs and symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease include:

- A burning sensation in your chest (heartburn), usually after eating, which might be worse at night

- Chest pain

- Difficulty swallowing

- Regurgitation of food or sour liquid

- Sensation of a lump in your throat

If you have nighttime acid reflux, you might also experience:

- Chronic cough

- Laryngitis

- New or worsening asthma

- Disrupted sleep

Gastroesophageal reflux disease complications

Over time, chronic inflammation in your esophagus can cause:

- Narrowing of the esophagus (esophageal stricture). Damage to the lower esophagus from stomach acid causes scar tissue to form. The scar tissue narrows the food pathway, leading to problems with swallowing.

- An open sore in the esophagus (esophageal ulcer). Stomach acid can wear away tissue in the esophagus, causing an open sore to form. An esophageal ulcer can bleed, cause pain and make swallowing difficult.

- Precancerous changes to the esophagus (Barrett’s esophagus). Damage from acid can cause changes in the tissue lining the lower esophagus. These changes are associated with an increased risk of esophageal cancer.

Gastroesophageal reflux disease causes

Gastroesophageal reflux disease is caused by frequent acid reflux.

When you swallow, a circular band of muscle around the bottom of your esophagus (lower esophageal sphincter) relaxes to allow food and liquid to flow into your stomach. Then the sphincter closes again.

If the sphincter relaxes abnormally or weakens, stomach acid can flow back up into your esophagus. This constant backwash of acid irritates the lining of your esophagus, often causing it to become inflamed.

Risk factors for gastroesophageal reflux disease

Conditions that can increase your risk of gastroesophageal reflux disease include:

- Obesity

- Bulging of the top of the stomach up into the diaphragm (hiatal hernia)

- Pregnancy

- Connective tissue disorders, such as scleroderma

- Delayed stomach emptying

Factors that can aggravate acid reflux include:

- Smoking

- Eating large meals or eating late at night

- Eating certain foods (triggers) such as fatty or fried foods

- Drinking certain beverages, such as alcohol or coffee

- Taking certain medications, such as aspirin

Gastroesophageal reflux disease diagnosis

Your doctor might be able to diagnose gastroesophageal reflux disease based on a physical examination and history of your signs and symptoms.

To confirm a diagnosis of gastroesophageal reflux disease, or to check for complications, your doctor might recommend:

- Upper endoscopy. Your doctor inserts a thin, flexible tube equipped with a light and camera (endoscope) down your throat, to examine the inside of your esophagus and stomach. Test results can often be normal when reflux is present, but an endoscopy may detect inflammation of the esophagus (esophagitis) or other complications. An endoscopy can also be used to collect a sample of tissue (biopsy) to be tested for complications such as Barrett’s esophagus.

- Ambulatory acid (pH) probe test. A monitor is placed in your esophagus to identify when, and for how long, stomach acid regurgitates there. The monitor connects to a small computer that you wear around your waist or with a strap over your shoulder. The monitor might be a thin, flexible tube (catheter) that’s threaded through your nose into your esophagus, or a clip that’s placed in your esophagus during an endoscopy and that gets passed into your stool after about two days.

- Esophageal manometry. This test measures the rhythmic muscle contractions in your esophagus when you swallow. Esophageal manometry also measures the coordination and force exerted by the muscles of your esophagus.

- X-ray of your upper digestive system. X-rays are taken after you drink a chalky liquid that coats and fills the inside lining of your digestive tract. The coating allows your doctor to see a silhouette of your esophagus, stomach and upper intestine. You may also be asked to swallow a barium pill that can help diagnose a narrowing of the esophagus that may interfere with swallowing.

Gastroesophageal reflux disease treatment

Your doctor is likely to recommend that you first try lifestyle modifications and over-the-counter medications. If you don’t experience relief within a few weeks, your doctor might recommend prescription medication or surgery.

Over-the-counter medications

The options include:

- Antacids that neutralize stomach acid. Antacids, such as Mylanta, Rolaids and Tums, may provide quick relief. But antacids alone won’t heal an inflamed esophagus damaged by stomach acid. Overuse of some antacids can cause side effects, such as diarrhea or sometimes kidney problems.

- Medications to reduce acid production. These medications — known as H-2-receptor blockers — include cimetidine (Tagamet HB), famotidine (Pepcid AC), nizatidine (Axid AR) and ranitidine (Zantac). H-2-receptor blockers don’t act as quickly as antacids, but they provide longer relief and may decrease acid production from the stomach for up to 12 hours. Stronger versions are available by prescription.

- Medications that block acid production and heal the esophagus. These medications — known as proton pump inhibitors — are stronger acid blockers than H-2-receptor blockers and allow time for damaged esophageal tissue to heal. Over-the-counter proton pump inhibitors include lansoprazole (Prevacid 24 HR) and omeprazole (Prilosec OTC, Zegerid OTC).

Prescription medications

Prescription-strength treatments for gastroesophageal reflux disease include:

- Prescription-strength H-2-receptor blockers. These include prescription-strength famotidine (Pepcid), nizatidine and ranitidine (Zantac). These medications are generally well-tolerated but long-term use may be associated with a slight increase in risk of vitamin B-12 deficiency and bone fractures.

- Prescription-strength proton pump inhibitors. These include esomeprazole (Nexium), lansoprazole (Prevacid), omeprazole (Prilosec, Zegerid), pantoprazole (Protonix), rabeprazole (Aciphex) and dexlansoprazole (Dexilant). Although generally well-tolerated, these medications might cause diarrhea, headache, nausea and vitamin B-12 deficiency. Chronic use might increase the risk of hip fracture.

- Medication to strengthen the lower esophageal sphincter. Baclofen may ease gastroesophageal reflux disease by decreasing the frequency of relaxations of the lower esophageal sphincter. Side effects might include fatigue or nausea.

Surgery and other procedures

Gastroesophageal reflux disease can usually be controlled with medication. But if medications don’t help or you wish to avoid long-term medication use, your doctor might recommend:

- Fundoplication. The surgeon wraps the top of your stomach around the lower esophageal sphincter, to tighten the muscle and prevent reflux. Fundoplication is usually done with a minimally invasive (laparoscopic) procedure. The wrapping of the top part of the stomach can be partial or complete.

- LINX device. A ring of tiny magnetic beads is wrapped around the junction of the stomach and esophagus. The magnetic attraction between the beads is strong enough to keep the junction closed to refluxing acid, but weak enough to allow food to pass through. The Linx device can be implanted using minimally invasive surgery.

Lifestyle and home remedies

Lifestyle changes may help reduce the frequency of acid reflux. Try to:

- Maintain a healthy weight. Excess pounds put pressure on your abdomen, pushing up your stomach and causing acid to reflux into your esophagus.

- Stop smoking. Smoking decreases the lower esophageal sphincter’s ability to function properly.

- Elevate the head of your bed. If you regularly experience heartburn while trying to sleep, place wood or cement blocks under the feet of your bed so that the head end is raised by 6 to 9 inches. If you can’t elevate your bed, you can insert a wedge between your mattress and box spring to elevate your body from the waist up. Raising your head with additional pillows isn’t effective.

- Don’t lie down after a meal. Wait at least three hours after eating before lying down or going to bed.

- Eat food slowly and chew thoroughly. Put down your fork after every bite and pick it up again once you have chewed and swallowed that bite.

- Avoid foods and drinks that trigger reflux. Common triggers include fatty or fried foods, tomato sauce, alcohol, chocolate, mint, garlic, onion, and caffeine.

- Avoid tight-fitting clothing. Clothes that fit tightly around your waist put pressure on your abdomen and the lower esophageal sphincter.

Diverticulitis

Diverticulitis is a sometimes painful condition caused by inflammation or infection of abnormal pouches (diverticula) in the lower part of the large intestine. Diverticula are small, bulging pouches that can form in the lining of your digestive system. Diverticula are found most often in the lower part of the large intestine (colon). Diverticula are common, especially after age 40, and seldom cause problems.

Diverticulitis can cause severe abdominal pain, fever, nausea and a marked change in your bowel habits.

Mild diverticulitis can be treated with rest, changes in your diet and antibiotics. Severe or recurring diverticulitis may require surgery.

Diverticulitis causes

Diverticula usually develop when naturally weak places in your colon give way under pressure. This causes marble-sized pouches to protrude through the colon wall. Diverticulitis occurs when diverticula tear, resulting in inflammation or infection or both.

Risk factors for diverticulitis

Several factors may increase your risk of developing diverticulitis:

- Aging. The incidence of diverticulitis increases with age.

- Obesity. Being seriously overweight increases your odds of developing diverticulitis.

- Smoking. People who smoke cigarettes are more likely than nonsmokers to experience diverticulitis.

- Lack of exercise. Vigorous exercise appears to lower your risk of diverticulitis.

- Diet high in animal fat and low in fiber. A low-fiber diet in combination with a high intake of animal fat seems to increase risk, although the role of low fiber alone isn’t clear.

- Certain medications Several drugs are associated with an increased risk of diverticulitis, including steroids, opioids and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, such as ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin IB, others) and naproxen sodium (Aleve).

Diverticulitis prevention

To help prevent diverticulitis:

- Exercise regularly. Exercise promotes normal bowel function and reduces pressure inside your colon. Try to exercise at least 30 minutes on most days.

- Eat more fiber. A high-fiber diet decreases the risk of diverticulitis. Fiber-rich foods, such as fresh fruits and vegetables and whole grains, soften waste material and help it pass more quickly through your colon. Eating seeds and nuts isn’t associated with developing diverticulitis.

- Drink plenty of fluids. Fiber works by absorbing water and increasing the soft, bulky waste in your colon. But if you don’t drink enough liquid to replace what’s absorbed, fiber can be constipating.

Diverticulitis symptoms

The signs and symptoms of diverticulitis include:

- Pain, which may be constant and persist for several days. The lower left side of the abdomen is the usual site of the pain. Sometimes, however, the right side of the abdomen is more painful, especially in people of Asian descent.

- Nausea and vomiting.

- Fever.

- Abdominal tenderness.

- Constipation or, less commonly, diarrhea.

Diverticulitis complications

About 25 percent of people with acute diverticulitis develop complications, which may include:

- An abscess, which occurs when pus collects in the pouch.

- A blockage in your colon or small intestine caused by scarring.

- An abnormal passageway (fistula) between sections of bowel or the bowel and bladder.

- Peritonitis, which can occur if the infected or inflamed pouch ruptures, spilling intestinal contents into your abdominal cavity. Peritonitis is a medical emergency and requires immediate care.

Diverticulitis diagnosis

Diverticulitis is usually diagnosed during an acute attack. Because abdominal pain can indicate a number of problems, your doctor will need to rule out other causes for your symptoms.

Your doctor will likely start with a physical examination, which will include checking your abdomen for tenderness. Women generally have a pelvic examination as well to rule out pelvic disease.

After that, the following tests are likely:

- Blood and urine tests, to check for signs of infection.

- A pregnancy test for women of childbearing age, to rule out pregnancy as a cause of abdominal pain.

- A liver enzyme test, to rule out liver-related causes of abdominal pain.

- A stool test, to rule out infection in people who have diarrhea.

- A CT scan, which can identify inflamed or infected pouches and confirm a diagnosis of diverticulitis. CT can also indicate the severity of diverticulitis and guide treatment.

Diverticulitis treatment

Treatment depends on the severity of your signs and symptoms.

Uncomplicated diverticulitis

If your symptoms are mild, you may be treated at home. Your doctor is likely to recommend:

- Antibiotics to treat infection, although new guidelines state that in very mild cases, they may not be needed.

- A liquid diet for a few days while your bowel heals. Once your symptoms improve, you can gradually add solid food to your diet.

- An over-the-counter pain reliever, such as acetaminophen (Tylenol, others).

This treatment is successful in most people with uncomplicated diverticulitis.

Complicated diverticulitis

If you have a severe attack or have other health problems, you’ll likely need to be hospitalized. Treatment generally involves:

- Intravenous antibiotics

- Insertion of a tube to drain an abdominal abscess, if one has formed

Surgery

You’ll likely need surgery to treat diverticulitis if:

- You have a complication, such as a bowel abscess, fistula or obstruction, or a puncture (perforation) in the bowel wall

- You have had multiple episodes of uncomplicated diverticulitis

- You have a weakened immune system

There are two main types of surgery:

- Primary bowel resection. The surgeon removes diseased segments of your intestine and then reconnects the healthy segments (anastomosis). This allows you to have normal bowel movements. Depending on the amount of inflammation, you may have open surgery or a minimally invasive (laparoscopic) procedure.

- Bowel resection with colostomy. If you have so much inflammation that it’s not possible to rejoin your colon and rectum, the surgeon will perform a colostomy. An opening (stoma) in your abdominal wall is connected to the healthy part of your colon. Waste passes through the opening into a bag. Once the inflammation has eased, the colostomy may be reversed and the bowel reconnected.

Probiotics

Some experts suspect that people who develop diverticulitis may not have enough good bacteria in their colons. Probiotics — foods or supplements that contain beneficial bacteria — are sometimes suggested as a way to prevent diverticulitis. But that advice hasn’t been scientifically validated.

Follow-up care

Your doctor may recommend colonoscopy six weeks after you recover from diverticulitis, especially if you haven’t had the test in the previous year. There doesn’t appear to be a direct link between diverticular disease and colon or rectal cancer. But colonoscopy — which isn’t possible during a diverticulitis attack — can exclude colon cancer as a cause of your symptoms.

After successful treatment, your doctor may recommend surgery to prevent future episodes of diverticulitis. The decision on surgery is an individual one and is often based on the frequency of attacks and whether complications have occurred.

Peptic ulcers

Peptic ulcers are open sores that develop on the inside lining of your stomach and the upper portion of your small intestine. The most common symptom of a peptic ulcer is stomach pain.

Peptic ulcers include:

- Gastric ulcers that occur on the inside of the stomach

- Duodenal ulcers that occur on the inside of the upper portion of your small intestine (duodenum)

The most common causes of peptic ulcers are infection with the bacterium Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) and long-term use of aspirin and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (Advil, Aleve, others). Stress and spicy foods do not cause peptic ulcers. However, they can make your symptoms worse.

Peptic ulcer causes

Peptic ulcers occur when acid in the digestive tract eats away at the inner surface of the stomach or small intestine. The acid can create a painful open sore that may bleed.

Your digestive tract is coated with a mucous layer that normally protects against acid. But if the amount of acid is increased or the amount of mucus is decreased, you could develop an ulcer. Common causes include:

- A bacterium. Helicobacter pylori bacteria commonly live in the mucous layer that covers and protects tissues that line the stomach and small intestine. Often, the H. pylori bacterium causes no problems, but it can cause inflammation of the stomach’s inner layer, producing an ulcer. It’s not clear how H. pylori infection spreads. It may be transmitted from person to person by close contact, such as kissing. People may also contract H. pylori through food and water.

- Regular use of certain pain relievers. Taking aspirin, as well as certain over-the-counter and prescription pain medications called nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) can irritate or inflame the lining of your stomach and small intestine. These medications include ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin IB, others), naproxen sodium (Aleve, Anaprox, others), ketoprofen and others. They do not include acetaminophen (Tylenol). Peptic ulcers are more common in older adults who take these pain medications frequently or in people who take these medications for osteoarthritis.

- Other medications. Taking certain other medications along with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as steroids, anticoagulants, low-dose aspirin, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), alendronate (Fosamax) and risedronate (Actonel), can greatly increase the chance of developing ulcers.

Risk factors for peptic ulcer

In addition to taking nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), you may have an increased risk of peptic ulcers if you:

- Smoke. Smoking may increase the risk of peptic ulcers in people who are infected with H. pylori.

- Drink alcohol. Alcohol can irritate and erode the mucous lining of your stomach, and it increases the amount of stomach acid that’s produced.

- Have untreated stress.

- Eat spicy foods.

Alone, these factors do not cause ulcers, but they can make them worse and more difficult to heal.

Peptic ulcer prevention

You may reduce your risk of peptic ulcer if you follow the same strategies recommended as home remedies to treat ulcers. It may also be helpful to:

- Protect yourself from infections. It’s not clear just how H. pylori spreads, but there’s some evidence that it could be transmitted from person to person or through food and water. You can take steps to protect yourself from infections, such as H. pylori, by frequently washing your hands with soap and water and by eating foods that have been cooked completely.

- Use caution with pain relievers. If you regularly use pain relievers that increase your risk of peptic ulcer, take steps to reduce your risk of stomach problems. For instance, take your medication with meals. Work with your doctor to find the lowest dose possible that still gives you pain relief. Avoid drinking alcohol when taking your medication, since the two can combine to increase your risk of stomach upset. If you need an NSAID, you may need to also take additional medications such as an antacid, a proton-pump inhibitor (PPI), an acid blocker or cytoprotective agent. A class of NSAIDs called COX-2 inhibitors may be less likely to cause peptic ulcers, but may increase the risk of heart attack.

Peptic ulcer symptoms

- Burning stomach pain

- Feeling of fullness, bloating or belching

- Fatty food intolerance

- Heartburn

- Nausea

The most common peptic ulcer symptom is burning stomach pain. Stomach acid makes the pain worse, as does having an empty stomach. The pain can often be relieved by eating certain foods that buffer stomach acid or by taking an acid-reducing medication, but then it may come back. The pain may be worse between meals and at night.

Nearly three-quarters of people with peptic ulcers don’t have symptoms.

Less often, ulcers may cause severe signs or symptoms such as:

- Vomiting or vomiting blood — which may appear red or black

- Dark blood in stools, or stools that are black or tarry

- Trouble breathing

- Feeling faint

- Nausea or vomiting

- Unexplained weight loss

- Appetite changes

Peptic ulcer complications

Left untreated, peptic ulcers can result in:

- Internal bleeding. Bleeding can occur as slow blood loss that leads to anemia or as severe blood loss that may require hospitalization or a blood transfusion.

- Severe blood loss may cause black or bloody vomit or black or bloody stools.

- Infection. Peptic ulcers can eat a hole through (perforate) the wall of your stomach or small intestine, putting you at risk of serious infection of your abdominal cavity (peritonitis).

- Obstruction. Peptic ulcers can block passage of food through the digestive tract, causing you to become full easily, to vomit and to lose weight through either swelling from inflammation or scarring.

Peptic ulcer diagnosis

In order to detect an ulcer, your doctor may first take a medical history and perform a physical exam. You then may need to undergo diagnostic tests, such as:

- Laboratory tests for H. pylori. Your doctor may recommend tests to determine whether the bacterium H. pylori is present in your body. He or she may look for H. pylori using a blood, stool or breath test. The breath test is the most accurate. Blood tests are generally inaccurate and should not be routinely used. For the breath test, you drink or eat something that contains radioactive carbon. H. pylori breaks down the substance in your stomach. Later, you blow into a bag, which is then sealed. If you’re infected with H. pylori, your breath sample will contain the radioactive carbon in the form of carbon dioxide. If you are taking an antacid prior to the testing for H pylori, make sure to let your doctor know. Depending on which test is used, you may need to discontinue the medication for a period of time because antacids can lead to false-negative results.

- Endoscopy. Your doctor may use a scope to examine your upper digestive system (endoscopy). During endoscopy, your doctor passes a hollow tube equipped with a lens (endoscope) down your throat and into your esophagus, stomach and small intestine. Using the endoscope, your doctor looks for ulcers. If your doctor detects an ulcer, small tissue samples (biopsy) may be removed for examination in a lab. A biopsy can also identify whether H. pylori is in your stomach lining. Your doctor is more likely to recommend endoscopy if you are older, have signs of bleeding, or have experienced recent weight loss or difficulty eating and swallowing. If the endoscopy shows an ulcer in your stomach, a follow-up endoscopy should be performed after treatment to show that it has healed, even if your symptoms improve.

- Upper gastrointestinal series. Sometimes called a barium swallow, this series of X-rays of your upper digestive system creates images of your esophagus, stomach and small intestine. During the X-ray, you swallow a white liquid (containing barium) that coats your digestive tract and makes an ulcer more visible.

Peptic ulcer treatment

Treatment for peptic ulcers depends on the cause. Usually treatment will involve killing the H. pylori bacterium, if present, eliminating or reducing use of NSAIDs, if possible, and helping your ulcer to heal with medication.

Medications can include:

- Antibiotic medications to kill H. pylori. If H. pylori is found in your digestive tract, your doctor may recommend a combination of antibiotics to kill the bacterium. These may include amoxicillin (Amoxil), clarithromycin (Biaxin), metronidazole (Flagyl), tinidazole (Tindamax), tetracycline (Tetracycline HCL) and levofloxacin (Levaquin). The antibiotics used will be determined by where you live and current antibiotic resistance rates. You’ll likely need to take antibiotics for two weeks, as well as additional medications to reduce stomach acid, including a proton pump inhibitor and possibly bismuth subsalicylate (Pepto-Bismol).

- Medications that block acid production and promote healing. Proton pump inhibitors — also called PPIs — reduce stomach acid by blocking the action of the parts of cells that produce acid. These drugs include the prescription and over-the-counter medications omeprazole (Prilosec), lansoprazole (Prevacid), rabeprazole (Aciphex), esomeprazole (Nexium) and pantoprazole (Protonix). Long-term use of proton pump inhibitors, particularly at high doses, may increase your risk of hip, wrist and spine fracture. Ask your doctor whether a calcium supplement may reduce this risk.

- Medications to reduce acid production. Acid blockers — also called histamine (H-2) blockers — reduce the amount of stomach acid released into your digestive tract, which relieves ulcer pain and encourages healing. Available by prescription or over-the-counter, acid blockers include the medications ranitidine (Zantac), famotidine (Pepcid), cimetidine (Tagamet HB) and nizatidine (Axid AR).

- Antacids that neutralize stomach acid. Your doctor may include an antacid in your drug regimen. Antacids neutralize existing stomach acid and can provide rapid pain relief. Side effects can include constipation or diarrhea, depending on the main ingredients. Antacids can provide symptom relief, but generally aren’t used to heal your ulcer.

- Medications that protect the lining of your stomach and small intestine. In some cases, your doctor may prescribe medications called cytoprotective agents that help protect the tissues that line your stomach and small intestine. Options include the prescription medications sucralfate (Carafate) and misoprostol (Cytotec).

Follow-up after initial treatment

Treatment for peptic ulcers is often successful, leading to ulcer healing. But if your symptoms are severe or if they continue despite treatment, your doctor may recommend endoscopy to rule out other possible causes for your symptoms.

If an ulcer is detected during endoscopy, your doctor may recommend another endoscopy after your treatment to make sure your ulcer has healed. Ask your doctor whether you should undergo follow-up tests after your treatment.

Ulcers that fail to heal

Peptic ulcers that don’t heal with treatment are called refractory ulcers. There are many reasons why an ulcer may fail to heal, including:

- Not taking medications according to directions

- The fact that some types of H. pylori are resistant to antibiotics

- Regular use of tobacco

- Regular use of pain relievers — NSAIDs and aspirin — that increase the risk of ulcers

Less often, refractory ulcers may be a result of:

- Extreme overproduction of stomach acid, such as occurs in Zollinger-Ellison syndrome

- An infection other than H. pylori

- Stomach cancer

- Other diseases that may cause ulcer-like sores in the stomach and small intestine, such as Crohn’s disease

Treatment for refractory ulcers generally involves eliminating factors that may interfere with healing, along with using different antibiotics.

If you have a serious complication from an ulcer, such as acute bleeding or a perforation, you may require surgery. However, surgery is needed far less often than previously because of the many effective medications now available.

Lifestyle and home remedies

You may find relief from the pain of a stomach ulcer if you:

- Choose a healthy diet. Choose a healthy diet full of fruits, especially with vitamins A and C, vegetables, and whole grains. Not eating vitamin-rich foods may make it difficult for your body to heal your ulcer.

- Consider foods containing probiotics. These include yogurt, aged cheeses, miso, and sauerkraut.

- Consider eliminating milk. Sometimes drinking milk will make your ulcer pain better, but then later cause excess acid, which increases pain. Talk to your doctor about drinking milk.

- Consider switching pain relievers. If you use pain relievers regularly, ask your doctor whether acetaminophen (Tylenol, others) may be an option for you.

- Control stress. Stress may worsen the signs and symptoms of a peptic ulcer. Consider the sources of your stress and do what you can to address the causes. Some stress is unavoidable, but you can learn to cope with stress with exercise, spending time with friends or writing in a journal.

- Don’t smoke. Smoking may interfere with the protective lining of the stomach, making your stomach more susceptible to the development of an ulcer. Smoking also increases stomach acid.

- Limit or avoid alcohol. Excessive use of alcohol can irritate and erode the mucous lining in your stomach and intestines, causing inflammation and bleeding.

- Try to get enough sleep. Sleep can help your immune system, and therefore counter stress. Also, avoid eating shortly before bedtime.

Hemorrhoids

Hemorrhoids also called piles, are swollen veins in your anus and lower rectum, similar to varicose veins. Hemorrhoids have a number of causes, although often the cause is unknown. They may result from straining during bowel movements or from the increased pressure on these veins during pregnancy. Hemorrhoids may be located inside the rectum (internal hemorrhoids), or they may develop under the skin around the anus (external hemorrhoids).

Hemorrhoids are very common. Nearly three out of four adults will have hemorrhoids from time to time. Sometimes they don’t cause symptoms but at other times they cause itching, discomfort and bleeding.

Occasionally, a clot may form in a hemorrhoid (thrombosed hemorrhoid). These are not dangerous but can be extremely painful and sometimes need to be lanced and drained.

Fortunately, many effective options are available to treat hemorrhoids. Many people can get relief from symptoms with home treatments and lifestyle changes.

Bleeding during bowel movements is the most common sign of hemorrhoids. Your doctor can do a physical examination and perform other tests to confirm hemorrhoids and rule out more-serious conditions or diseases.

Also talk to your doctor if you know you have hemorrhoids and they cause pain, bleed frequently or excessively, or don’t improve with home remedies.

Don’t assume rectal bleeding is due to hemorrhoids, especially if you are over 40 years old. Rectal bleeding can occur with other diseases, including colorectal cancer and anal cancer. If you have bleeding along with a marked change in bowel habits or if your stools change in color or consistency, consult your doctor. These types of stools can signal more extensive bleeding elsewhere in your digestive tract.

Seek emergency care if you experience large amounts of rectal bleeding, lightheadedness, dizziness or faintness.

Hemorrhoids causes

The veins around your anus tend to stretch under pressure and may bulge or swell. Swollen veins (hemorrhoids) can develop from increased pressure in the lower rectum due to:

- Straining during bowel movements

- Sitting for long periods of time on the toilet

- Chronic diarrhea or constipation

- Obesity

- Pregnancy

- Anal intercourse

- Low-fiber diet

Hemorrhoids are more likely with aging because the tissues that support the veins in your rectum and anus can weaken and stretch.

Risk factors for hemorrhoids

As you get older, you’re at greater risk of hemorrhoids. That’s because the tissues that support the veins in your rectum and anus can weaken and stretch. This can also happen when you’re pregnant, because the baby’s weight puts pressure on the anal region.

Hemorrhoids prevention

The best way to prevent hemorrhoids is to keep your stools soft, so they pass easily. To prevent hemorrhoids and reduce symptoms of hemorrhoids, follow these tips:

- Eat high-fiber foods. Eat more fruits, vegetables and whole grains. Doing so softens the stool and increases its bulk, which will help you avoid the straining that can cause hemorrhoids. Add fiber to your diet slowly to avoid problems with gas.

- Drink plenty of fluids. Drink six to eight glasses of water and other liquids (not alcohol) each day to help keep stools soft.

- Consider fiber supplements. Most people don’t get enough of the recommended amount of fiber — 25 grams a day for women and 38 grams a day for men — in their diet. Studies have shown that over-the-counter fiber supplements, such as Metamucil and Citrucel, improve overall symptoms and bleeding from hemorrhoids. These products help keep stools soft and regular. If you use fiber supplements, be sure to drink at least eight glasses of water or other fluids every day. Otherwise, the supplements can cause constipation or make constipation worse.

- Don’t strain. Straining and holding your breath when trying to pass a stool creates greater pressure in the veins in the lower rectum.

- Go as soon as you feel the urge. If you wait to pass a bowel movement and the urge goes away, your stool could become dry and be harder to pass.

- Exercise. Stay active to help prevent constipation and to reduce pressure on veins, which can occur with long periods of standing or sitting. Exercise can also help you lose excess weight that may be contributing to your hemorrhoids.

- Avoid long periods of sitting. Sitting too long, particularly on the toilet, can increase the pressure on the veins in the anus.

Hemorrhoids symptoms

Signs and symptoms of hemorrhoids may include:

- Painless bleeding during bowel movements — you might notice small amounts of bright red blood on your toilet tissue or in the toilet

- Itching or irritation in your anal region

- Pain or discomfort

- Swelling around your anus

- A lump near your anus, which may be sensitive or painful (may be a thrombosed hemorrhoid)

Hemorrhoid symptoms usually depend on the location.

- Internal hemorrhoids. These lie inside the rectum. You usually can’t see or feel these hemorrhoids, and they rarely cause discomfort. But straining or irritation when passing stool can damage a hemorrhoid’s surface and cause it to bleed. Occasionally, straining can push an internal hemorrhoid through the anal opening. This is known as a protruding or prolapsed hemorrhoid and can cause pain and irritation.

- External hemorrhoids. These are under the skin around your anus. When irritated, external hemorrhoids can itch or bleed.

- Thrombosed hemorrhoids. Sometimes blood may pool in an external hemorrhoid and form a clot (thrombus) that can result in severe pain, swelling, inflammation and a hard lump near your anus.

Hemorrhoids complications

Complications of hemorrhoids are very rare but include:

- Anemia. Rarely, chronic blood loss from hemorrhoids may cause anemia, in which you don’t have enough healthy red blood cells to carry oxygen to your cells.

- Strangulated hemorrhoid. If the blood supply to an internal hemorrhoid is cut off, the hemorrhoid may be “strangulated,” another cause of extreme pain.

Hemorrhoids diagnosis

Your doctor may be able to see if you have external hemorrhoids simply by looking. Tests and procedures to diagnose internal hemorrhoids may include examination of your anal canal and rectum:

- Digital examination. During a digital rectal exam, your doctor inserts a gloved, lubricated finger into your rectum. He or she feels for anything unusual, such as growths. The exam can suggest to your doctor whether further testing is needed.

- Visual inspection. Because internal hemorrhoids are often too soft to be felt during a rectal exam, your doctor may also examine the lower portion of your colon and rectum with an anoscope, proctoscope or sigmoidoscope.

Your doctor may want to examine your entire colon using colonoscopy if:

- Your signs and symptoms suggest you might have another digestive system disease

- You have risk factors for colorectal cancer

- You’re middle-aged and haven’t had a recent colonoscopy

Hemorrhoids treatment

Home remedies

You can often relieve the mild pain, swelling and inflammation of hemorrhoids with home treatments. Often these are the only treatments needed.

- Eat high-fiber foods. Eat more fruits, vegetables and whole grains. Doing so softens the stool and increases its bulk, which will help you avoid the straining that can worsen symptoms from existing hemorrhoids. Add fiber to your diet slowly to avoid problems with gas.

- Use topical treatments. Apply an over-the-counter hemorrhoid cream or suppository containing hydrocortisone, or use pads containing witch hazel or a numbing agent.

- Soak regularly in a warm bath or sitz bath. Soak your anal area in plain warm water 10 to 15 minutes two to three times a day. A sitz bath fits over the toilet.

- Keep the anal area clean. Bathe (preferably) or shower daily to cleanse the skin around your anus gently with warm water. Avoid alcohol-based or perfumed wipes. Gently pat the area dry or use a hair dryer.

- Don’t use dry toilet paper. To help keep the anal area clean after a bowel movement, use moist towelettes or wet toilet paper that doesn’t contain perfume or alcohol.

- Apply cold. Apply ice packs or cold compresses on your anus to relieve swelling.

- Take oral pain relievers. You can use acetaminophen (Tylenol, others), aspirin or ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin IB, others) temporarily to help relieve your discomfort.

With these treatments, hemorrhoid symptoms often go away within a week. See your doctor if you don’t get relief in a week, or sooner if you have severe pain or bleeding.

Medications

If your hemorrhoids produce only mild discomfort, your doctor may suggest over-the-counter creams, ointments, suppositories or pads. These products contain ingredients, such as witch hazel, or hydrocortisone and lidocaine, that can relieve pain and itching, at least temporarily.

Don’t use an over-the-counter steroid cream for more than a week unless directed by your doctor because it may cause your skin to thin.

External hemorrhoid thrombectomy

If a painful blood clot (thrombosis) has formed within an external hemorrhoid, your doctor can remove the clot with a simple incision and drainage, which may provide prompt relief. This procedure is most effective if done within 72 hours of developing a clot.

Minimally invasive procedures

For persistent bleeding or painful hemorrhoids, your doctor may recommend one of the other minimally invasive procedures available. These treatments can be done in your doctor’s office or other outpatient setting and do not usually require anesthesia.

- Rubber band ligation. Your doctor places one or two tiny rubber bands around the base of an internal hemorrhoid to cut off its circulation. The hemorrhoid withers and falls off within a week. This procedure is effective for many people. Hemorrhoid banding can be uncomfortable and may cause bleeding, which might begin two to four days after the procedure but is rarely severe. Occasionally, more-serious complications can occur.

- Injection (sclerotherapy). In this procedure, your doctor injects a chemical solution into the hemorrhoid tissue to shrink it. While the injection causes little or no pain, it may be less effective than rubber band ligation.

- Coagulation (infrared, laser or bipolar). Coagulation techniques use laser or infrared light or heat. They cause small, bleeding, internal hemorrhoids to harden and shrivel. While coagulation has few side effects and may cause little immediate discomfort, it’s associated with a higher rate of hemorrhoids coming back (recurrence) than is the rubber band treatment.

Surgical procedures

If other procedures haven’t been successful or you have large hemorrhoids, your doctor may recommend a surgical procedure. Your surgery may be done as an outpatient or may require an overnight hospital stay.

- Hemorrhoid removal. In this procedure, called hemorrhoidectomy, your surgeon removes excessive tissue that causes bleeding. Various techniques may be used. The surgery may be done with a local anesthetic combined with sedation, a spinal anesthetic or a general anesthetic. Hemorrhoidectomy is the most effective and complete way to treat severe or recurring hemorrhoids. Complications may include temporary difficulty emptying your bladder and resulting urinary tract infections. Most people experience some pain after the procedure. Medications can relieve your pain. Soaking in a warm bath also may help.

- Hemorrhoid stapling. This procedure, called stapled hemorrhoidectomy or stapled hemorrhoidopexy, blocks blood flow to hemorrhoidal tissue. It is typically used only for internal hemorrhoids. Stapling generally involves less pain than hemorrhoidectomy and allows for earlier return to regular activities. Compared with hemorrhoidectomy, however, stapling has been associated with a greater risk of recurrence and rectal prolapse, in which part of the rectum protrudes from the anus. Complications can also include bleeding, urinary retention and pain, as well as, rarely, a life-threatening blood infection (sepsis). Talk with your doctor about the best option for you.

Gastrointestinal infection

If you have a gastrointestinal infection, it means that disease-causing microorganisms (‘bugs’ or germs) have found their way into your gut, which is part of your digestive system.

An infection of the gastrointestinal is sometimes called a gastrointestinal infection, or gastroenteritis.

People commonly get infected by:

- eating or drinking contaminated water or food (often called food poisoning)

- coming into contact with infected people, or contaminated objects such as cutlery, taps, toys or nappies.

Bowel infections are common in Australia, but it’s also common to get one when travelling overseas.

Common types of gastrointestinal infection

Many different types of organism can cause gastrointestinal infections. Some of the more common ones found in Australia are listed below.

Bowel infections caused by viruses include:

- Rotavirus – common in young children; spreads easily through contact with contaminated vomit or feces

- Norovirus – highly contagious and spreads easily in places like child care centers, nursing homes and cruise ships.

Bowel infections caused by bacteria include:

- Campylobacter – often linked with eating contaminated chicken; people most at risk are the young, the elderly, travelers and people who are malnourished

- Salmonella – usually spread via contaminated meat, poultry or eggs

- Shigella – most common in travelers to developing countries.

Bowel infections caused by parasites include:

- Giardia – spread in the feces of infected people and animals; most common in young children, hikers, and travelers

- Cryptosporidiosis – spread by contaminated food or water

- Amebiasis – mostly affects young adults; usually spread via contaminated water or food.

If you often get gastrointestinal symptoms like diarrhea, it could be a sign that you have an underlying condition such as diverticulitis, Crohn’s disease, irritable gastrointestinal syndrome or ulcerative colitis. You should see your doctor for advice.

Gastrointestinal infection prevention

Many gastrointestinal infections can be prevented by taking care with what you eat and drink, and by following good hygiene practices.

- Cook foods such as meat and eggs thoroughly.

- Wash your hands regularly, especially before touching food.

- When traveling to developing nations, only use bottled water for drinking and teeth cleaning, and avoid ice and raw foods.

- Avoid close contact with people who have a gastrointestinal infection.

Gastrointestinal infection symptoms

The symptoms of a gastrointestinal infection can vary depending on the cause. Some common symptoms include:

- diarrhea

- nausea

- vomiting

- crampy abdominal pain

- fever

- headache.

Some people also get blood in their stools, known as dysentery, which can be caused by some bacteria and parasites.

You should see a doctor if you have:

- severe symptoms

- a high temperature (fever)

- blood or mucus in your stools

- diarrhea that lasts longer than 2 or 3 days

- signs of dehydration, such as excessive thirst or not passing much urine.

Babies should see a doctor urgently if:

- they have passed 6 or more diarrhea stools in 24 hours

- they have vomited 3 or more times in 24 hours

- they are unwell – less responsive, not feeding well, feverish or not passing much urine

- vomiting has lasted more than a day.

Toddlers and young children should see a doctor if:

- they have diarrhea and vomiting at the same time

- they have diarrhea that’s particularly watery, has blood in it or lasts for longer than 2 or 3 days

- they have severe or continuous stomach ache.

Gastrointestinal infection diagnosis

To diagnose the cause of your symptoms, your doctor may ask some questions and examine you. They might also do some tests, such as:

- fecal testing (stool sample)

- blood tests

- endoscopy (such as colonoscopy) to look inside your gastrointestinal tract.

In some cases, you might be referred to an infectious diseases service.

Gastrointestinal infection treatment

Most gastrointestinal infections clear up after a few days. However, it’s important that you drink plenty of fluids, including water and oral rehydration drinks, available from a pharmacist, to avoid dehydration.

Diarrhea causes a lot of fluids to be lost from the body, so take special care of vulnerable people like the very young, the very old and those in poor health.

Some people need antibiotics for gastrointestinal infections caused by parasites and bacteria. If your symptoms persist, see a doctor.

Gastrointestinal bleeding

Gastrointestinal bleeding can fall into two broad categories: upper and lower sources of bleeding. The anatomic landmark that separates upper and lower bleeds is the ligament of Treitz, also known as the suspensory ligament of the duodenum. This peritoneal structure suspends the duodenojejunal flexure from the retroperitoneum. Bleeding that originates above the ligament of Treitz usually presents either as hematemesis or melena whereas bleeding that originates below most commonly presents as hematochezia. Hematemesis is the regurgitation of blood or blood mixed with stomach contents. Melena is dark, black, and tarry feces that typically has a strong characteristic odor caused by the digestive enzyme activity and intestinal bacteria on hemoglobin. Hematochezia is the passing of bright red blood via the rectum.

Upper gastrointestinal bleeding is more common than lower gastrointestinal bleeding 1:

- Upper gastrointestinal bleeding approx. 67/100,000 population

- Lower gastrointestinal bleeding approx. 36/100,000 population

- More common with increasing age

- More common in men

- Overall incidence is decreasing nationwide

Upper gastrointestinal bleeding

- Peptic ulcer disease (can be secondary to excess gastric acid, H. pylori infection, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) overuse, or physiologic stress)

- Esophagitis

- Gastritis and Duodenitis

- Varices

- Portal Hypertensive Gastropathy

- Angiodysplasia

- Dieulafoy’s lesion (bleeding dilated vessel that erodes through the gastrointestinal epithelium but has no primary ulceration; can any location along the GI tract 2

- Gastric Antral Valvular Ectasia (GAVE; also known as watermelon stomach)

- Mallory-Weiss tears

- Cameron lesions (bleeding ulcers occurring at the site of a hiatal hernia 3

- Aortoenteric fistulas

- Foreign body ingestion

- Post-surgical bleeds (post-anastomotic bleeding, post-polypectomy bleeding, post-sphincterotomy bleeding)

- Upper gastrointestinal tumors

- Hemobilia (bleeding from the biliary tract)

- Hemosuccus pancreaticus (bleeding from the pancreatic duct)

Lower gastrointestinal bleeding

- Diverticulosis (colonic wall protrusion at the site of penetrating vessels; over time mucosa overlying the vessel can be injured and rupture leading to bleeding)

- Angiodysplasia

- Infectious Colitis

- Ischemic Colitis

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease

- Colon cancer

- Hemorrhoids

- Anal fissures

- Rectal varices

- Dieulafoy’s lesion (more rarely found outside of the stomach, but can be found throughout gastrointestinal tract)

- Radiation-induced damage following treatment of abdominal or pelvic cancers

- Post-surgical (post-polypectomy bleeding, post-biopsy bleeding)

Gastrointestinal bleeding complications

- Respiratory Distress

- Myocardial Infarction

- Infection

- Shock

- Death

Gastrointestinal bleeding diagnosis

Lab tests

- Complete blood count

- Hemoglobin/Hematocrit

- INR, PT, PTT

- Lactate

- Liver function tests

Diagnostic studies

- Upper Endoscopy

- Can be diagnostic and therapeutic

- Allows visualization of the upper gastrointestinal tract (typically including from the oral cavity up to the duodenum) and treatment with injection therapy, thermal coagulation, or hemostatic clips/bands

- Lower Endoscopy/Colonoscopy

- Can be diagnostic and therapeutic

- Allows visualization of the lower gastrointestinal tract (including the colon and terminal ileum) and treatment with injection therapy, thermal coagulation, or hemostatic clips/bands

- Push enteroscopy

- Allows further visualization of the small bowel

- Deep small bowel enteroscopy

- Allows further visualization of the small bowel

- Nuclear Scintigraphy

- Tagged red blood cell scan

- Detects bleeding occurring at a rate of 0.1 to 0.5mL/min using technetium-99m (can only detect active bleeding 4

- Can be helpful to localize angiographic and surgical interventions

- CT Angiography

Allows for identification of an actively bleeding vessel - Standard angiography

- Meckel’s scan

- Nuclear medicine scan to look for ectopic gastric mucosa

Gastrointestinal bleeding treatment

Acute management of gastrointestinal bleeding typically involves an assessment of the appropriate setting for treatment followed by resuscitation and supportive therapy while investigating the underlying cause and attempting to correct it.

Risk stratification

Specific risk calculators attempt to help identify patients who would benefit from ICU level of care; most stratify based on mortality risk. The AIMS65 score and the Rockall Score calculate the mortality rate of upper gastrointestinal bleeds. There are two separate Rockall scores; One is calculated before endoscopy and identifies pre-endoscopy mortality, whereas the second score is calculated post-endoscopy and calculates overall mortality and re-bleeding risks. The Oakland Score is a risk calculator that attempts to help calculate the probability of a safe discharge in lower gastrointestinal bleeds.[10]

Setting

- ICU: Patients with hemodynamic instability, continuous bleeding, or those with a significant risk of morbidity/mortality should undergo monitoring in an intensive care unit to facilitate more frequent observation of vital signs and more emergent therapeutic intervention.

- General Medical Ward: Most other patients can undergo monitoring on a general medical floor. However, they would likely benefit from continuous telemetry monitoring for earlier recognition of hemodynamic compromise

- Outpatient: Most patients with gastrointestinal bleeding will require hospitalization. However, some young, healthy patients with self-limited and asymptomatic bleeding may be safely discharged and evaluated on an outpatient basis.

Treatments

- Nothing by mouth

- Provide supplemental oxygen if patient hypoxic (typically via nasal cannula, but patients with ongoing hematemesis or altered mental status may require intubation). Avoid nasal intermittent positive pressure ventilation (NIPPV) due to the risk of aspiration with ongoing vomiting.

- Adequate IV access – at least two large-bore peripheral IVs (18 gauge or larger) or a centrally placed cordis

- IV fluid resuscitation (with Normal Saline or Lactated Ringer’s solution)

- Type and Cross

- Transfusions

- Red blood cell transfusion: Typically started if hemoglobin is < 7g/dL, including in patients with coronary heart disease[11][12]

- Platelet transfusion started if platelet count < 50,000/microL

- Prothrombin complex concentrate: Transfuse if INR > 2

- Medications

- Proton-pump inhibitors (PPIs): Used empirically for upper gastrointestinal bleeds and can be continued or discontinued upon identification of the bleeding source

- Prokinetic Agents: Given to improve visualization at the time of endoscopy

- Vasoactive medications: Somatostatin and its analog octreotide can be used to treat variceal bleeding by inhibiting vasodilatory hormone release[13]

- Antibiotics: Considered prophylactically in patients with cirrhosis to prevent translocation, especially from endoscopy

- Anticoagulant/antiplatelet agents: Should be stopped if possible in acute bleeds

- Consider the reversal of agents on a case-by-case basis dependent on the severity of bleeding and risks of reversal

- Other

- Consider nasogastric tube lavage if necessary to remove fresh blood or clots to facilitate endoscopy

- Placement of a Blakemore or Minnesota tube should be considered in patients with hemodynamic instability/massive gastrointestinal bleeds in the setting of known varices, which should be done only once the airway is secured. This procedure carries a significant complication risk (including arrhythmias, gastric or esophageal perforation) and should only be done by an experienced provider as a temporizing measure.

- Surgery should be consulted promptly in patients with massive bleeding or hemodynamic instability who have bleeding that is not amenable to any other treatment

Gastrointestinal prognosis

Limited studies exist regarding the prognosis following gastrointestinal bleeding.

For upper gastrointestinal bleeds, in-hospital mortality rates are approximately 10% based on observational studies. This rate holds steady up to 1-month post-hospitalization for gastrointestinal bleed. Long-term follow-up of patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding shows that at three years after admission mortality rates from all causes approach 37%.

Mortality rates were higher in women than in men when adjusted for age, which differs from that of lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Patients with multiple hospitalizations for gastrointestinal bleeding carry higher mortality rates. Long-term prognosis was worst in patients who suffered from malignancies and variceal bleeds. The prognosis was worse with advancing age 7.

For lower gastrointestinal bleeds, all-cause in-hospital mortality is low—less than 4%. Death from lower gastrointestinal bleeding itself is rare, with most in-hospital mortality occurring from other comorbid conditions. Increased risk of death corresponded to increasing age (as seen in cases of upper gastrointestinal bleeding as well), comorbid conditions, and intestinal ischemia. Other negative prognostic factors include secondary bleeding (onset of bleed after being hospitalized for a different condition), patients with pre-existing coagulopathies, hypovolemia, transfusion requirement, and male sex. Not surprisingly, the lowest risks of mortality are associated with more benign causes of lower gastrointestinal bleeding such as hemorrhoids, anal fissures, and colon polyps 8. Long-term follow-up studies in patients with lower gastrointestinal bleeding are not common.

- Wuerth BA, Rockey DC. Changing Epidemiology of Upper Gastrointestinal Hemorrhage in the Last Decade: A Nationwide Analysis. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2018 May;63(5):1286-1293[↩]

- Lee YT, Walmsley RS, Leong RW, Sung JJ. Dieulafoy’s lesion. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2003 Aug;58(2):236-43[↩]

- Weston AP. Hiatal hernia with cameron ulcers and erosions. Gastrointest. Endosc. Clin. N. Am. 1996 Oct;6(4):671-9[↩]

- Dusold R, Burke K, Carpentier W, Dyck WP. The accuracy of technetium-99m-labeled red cell scintigraphy in localizing gastrointestinal bleeding. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 1994 Mar;89(3):345-8.[↩]

- Funaki B. Endovascular intervention for the treatment of acute arterial gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Gastroenterol. Clin. North Am. 2002 Sep;31(3):701-13[↩]

- Walker TG. Acute gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Tech Vasc Interv Radiol. 2009 Jun;12(2):80-91[↩]

- Roberts SE, Button LA, Williams JG. Prognosis following upper gastrointestinal bleeding. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(12):e49507[↩]

- Strate LL, Ayanian JZ, Kotler G, Syngal S. Risk factors for mortality in lower intestinal bleeding. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2008 Sep;6(9):1004-10; quiz 955[↩]