GIST tumor

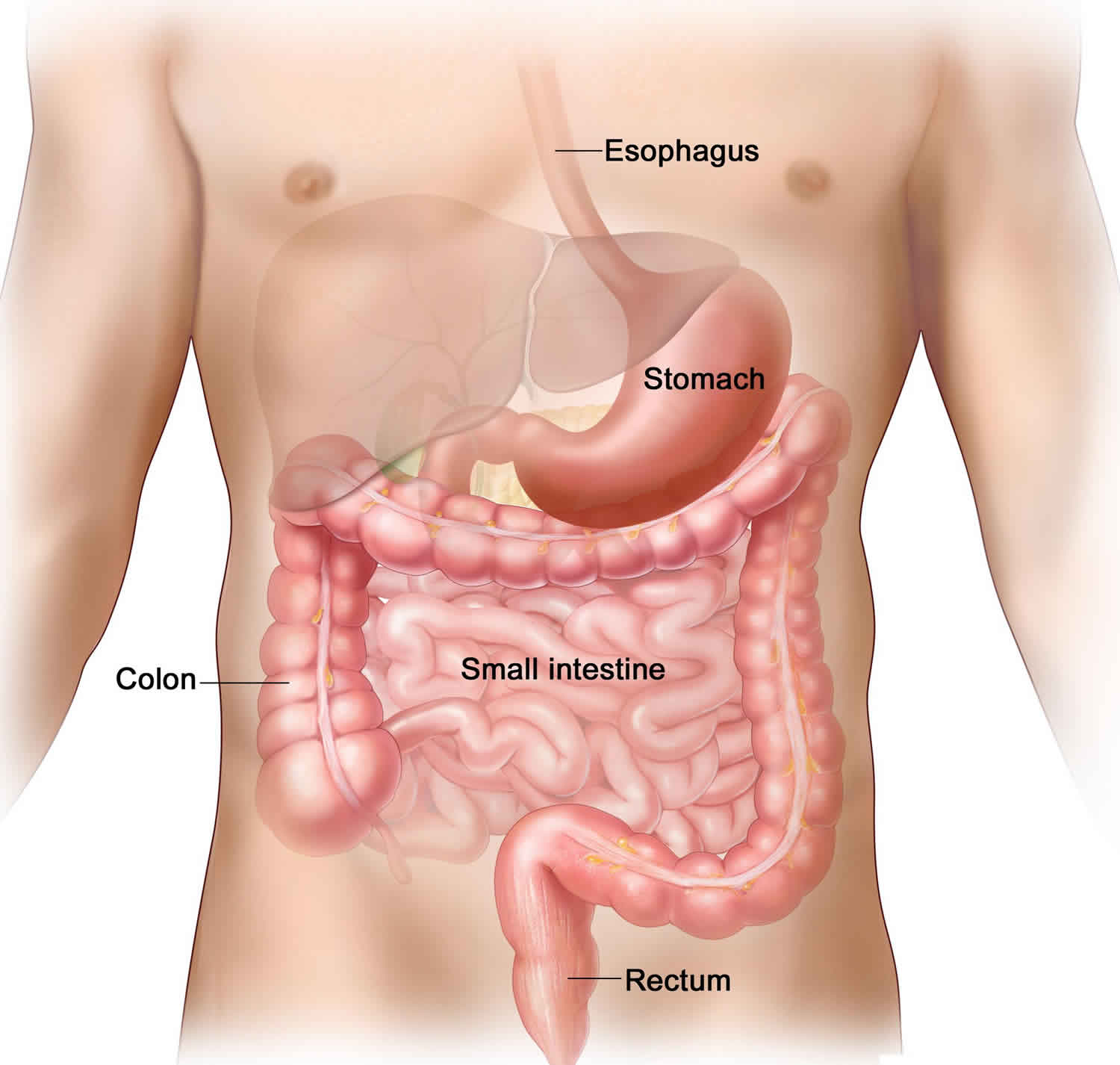

GIST tumor is short for gastrointestinal stromal tumor, is a rare type of tumor that occurs in the gastrointestinal tract, most commonly in the stomach or small intestine, but may be found anywhere in or near the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) may be malignant (cancer) or benign (not cancer). Some scientists believe that GISTs grow from specialized cells found in the gastrointestinal tract called interstitial cells of Cajal or precursors to these cells in the wall of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. GIST tumors are usually found in adults between ages 40 and 70; rarely, children and young adults develop GIST tumors. Approximately 5,000 new cases of GIST tumors are diagnosed in the United States each year. However, GIST tumors may be more common than this estimate because small tumors may remain undiagnosed.

Most gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) occur in the stomach or small intestine. These tumors often grow into the empty space inside the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, so they might not cause symptoms right away unless they are in a certain location or reach a certain size. Many GISTs don’t cause symptoms right away. Small tumors may cause no signs or symptoms. Sometimes they are found when a person has an exam or test done for another problem. However, some people with a GIST may experience pain or swelling in the abdomen, nausea, vomiting, loss of appetite, or weight loss. Sometimes, gastrointestinal stromal tumors cause bleeding, which may lead to low red blood cell counts (anemia) and consequently, weakness and tiredness. Bleeding into the intestinal tract may cause bloody or dark colored stools (poop) and bleeding into the throat or stomach may cause vomiting of blood.

Affected individuals with no family history of GIST tumor typically have only one tumor called a sporadic GIST. People with a family history of GIST tumor called familial GIST often have multiple tumors and additional signs or symptoms, including noncancerous overgrowth (hyperplasia) of other cells in the gastrointestinal tract and patches of dark skin on various areas of the body. Some affected individuals have a skin condition called urticaria pigmentosa (also known as cutaneous mastocytosis), which is characterized by raised patches of brownish skin that sting or itch when touched.

These and other signs and symptoms may be caused by a GIST or by other conditions. Check with your doctor if you have any of the following:

- Blood (either bright red or very dark) in the stool or vomit.

- Pain in the abdomen, which may be severe.

- Feeling very tired.

- Trouble or pain when swallowing.

- Feeling full after only a little food is eaten.

GIST cells can sometimes spread to other parts of the body. For instance, GIST cells in the stomach might travel to the liver and grow there. When cancer cells do this, it’s called metastasis. To doctors, the cancer cells in the new place look just like the ones from the stomach.

Cancer is always named based on the place where it starts. So when a GIST spreads to the liver (or any other place), it’s still called a GIST. It’s not called liver cancer unless it starts from cells in the liver.

Your treatment depends on the size and position of the gastrointestinal stromal tumor and your general health. Your specialist will discuss this with you.

GIST tumor key points

- Gastrointestinal stromal tumor is a disease in which abnormal cells form in the tissues of the gastrointestinal tract.

- Genetic factors can increase the risk of having a gastrointestinal stromal tumor.

- Signs of gastrointestinal stromal tumors include blood in the stool or vomit.

- Tests that examine the GI tract are used to detect (find) and diagnose gastrointestinal stromal tumors.

- Very small GISTs are common.

- Certain factors affect prognosis (chance of recovery) and treatment options.

GIST tumor causes

Scientists do not know exactly what causes most gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs). But in recent years, scientists have made great progress in learning how certain changes in DNA can cause normal cells to become cancerous. Genetic changes in one of several genes are involved in the formation of GIST tumors. About 80 percent of cases are associated with a mutation in the KIT gene, and about 10 percent of cases are associated with a mutation in the PDGFRA gene. Mutations in the KIT and PDGFRA genes are associated with both familial and sporadic GIST tumors. A small number of affected individuals have mutations in other genes. A small number of GISTs, especially those in children, do not have changes in either of these genes. Many of these GIST tumors have changes in one of the SDH genes. Researchers are still trying to determine what other gene changes can lead to these cancers.

The KIT and PDGFRA genes provide instructions for making receptor proteins that are found in the cell membrane of certain cell types and stimulate signaling pathways inside the cell. Receptor proteins have specific sites into which certain other proteins, called ligands, fit like keys into locks. When the ligand attaches (binds), the KIT or PDGFRA receptor protein is turned on (activated), which leads to activation of a series of proteins in multiple signaling pathways. These signaling pathways control many important cellular processes, such as cell growth and division (proliferation) and survival.

Mutations in the KIT and PDGFRA genes lead to proteins that no longer require ligand binding to be activated. As a result, the proteins and the signaling pathways are constantly turned on (constitutively activated), which increases the proliferation and survival of cells. When these mutations occur in interstitial cells of Cajal or their precursors, the uncontrolled cell growth leads to GIST tumor formation.

Risk factors for gastrointestinal stromal tumor

A risk factor is anything that affects a person’s chance of getting a disease like cancer. Different cancers have different risk factors. Some risk factors, like smoking, can be changed. Others, like a person’s age or family history, can’t be changed.

But having a risk factor, or even several, does not mean that a person will get the disease. And many people who get the disease may have few or no known risk factors.

Currently, there are very few known risk factors for gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs).

Being older

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors can occur in people of any age, but they are rare in people younger than 40 and are most common in people aged 50 to 80.

Genetic syndromes

Most GISTs are sporadic (not inherited) and have no clear cause. In rare cases, though, GISTs have been found in several members of the same family. These family members have inherited a gene mutation (change) that can lead to GISTs.

Primary familial GIST syndrome: This is a rare, inherited condition that leads to an increased risk of developing GISTs. People with this condition tend to develop GISTs at a younger age than when they usually occur. They are also more likely to have more than one GIST.

Most often, this syndrome is caused by an abnormal KIT gene passed from parent to child. This is the same gene that is mutated (changed) in most sporadic GISTs. People who inherited this abnormal gene from a parent have it in all their cells, while people with sporadic GISTs only have it in the cancer cells.

Less often, a change in the PDGFRA gene causes this genetic syndrome. Defects in the PDGFRA gene are found in about 5% to 10% of sporadic GISTs.

Sometimes people with familial GIST syndrome also have skin spots like those seen in patients with neurofibromatosis (discussed below). Before tests for the KIT and PDGFRA genes became available, some of these people were mistakenly thought to have neurofibromatosis.

Neurofibromatosis type 1 (von Recklinghausen disease)

von Recklinghausen disease (neurofibromatosis type 1) is caused by a defect in the NF1 gene. This gene change may be inherited from a parent, but in some cases it occurs before birth, without being inherited.

People affected by this syndrome often have many benign (non-cancerous) tumors that form in nerves, called neurofibromas, starting at an early age. These tumors form under the skin and in other parts of the body. These people also typically have tan or brown spots on the skin (called café au lait spots).

People with this condition have a higher risk of GISTs, as well as some other types of cancer.

Carney-Stratakis syndrome

People with this rare inherited condition have an increased risk of GISTs (most often in the stomach), as well as nerve tumors called paragangliomas. GISTs often develop when these people are in their teens or 20s. They are also more likely to have more than one GIST.

Carney-Stratakis syndrome is caused by a change in one of the succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) genes, which is passed from parent to child.

GIST tumor symptoms

People with an early stage GIST often do not have any symptoms. So an early stage GIST may be found when people are having tests for other medical conditions.

GIST tumors tend to be fragile tumors that can bleed easily. In fact, they are often found because they cause bleeding into the GI tract. Signs and symptoms of this bleeding depend on how fast it occurs and where the tumor is located.

- Brisk bleeding into the esophagus or stomach can cause the person to throw up blood. When the blood is thrown up it may be partially digested, so it might look like coffee grounds.

- Brisk bleeding into the stomach or small intestine can make bowel movements (stools) black and tarry.

- Brisk bleeding into the large intestine is likely to turn the stool red with visible blood.

- If the bleeding is slow, it often doesn’t cause the person to throw up blood or have a change in their stool. Over time, though, slow bleeding can lead to a low red blood cell count (anemia), and make a person feel tired and weak.

Bleeding from the GI tract can be very serious. If you have any of these signs or symptoms, see a doctor right away.

Most GISTs are diagnosed in later stages of the disease. The symptoms of an advanced GIST are likely to include:

- Pain or discomfort in the belly (abdomen)

- A feeling of fullness

- A mass or swelling in the abdomen

- Feeling full after eating only a small amount of food

- Being sick

- Loss of appetite

- Nausea and vomiting

- Blood in your stools or vomit

- Feeling very tired

- A low red blood cell count (anemia)

- Weight loss

- Problems swallowing (for tumors in the esophagus)

Sometimes GIST tumor grows large enough to block the passage of food through the stomach or intestine. This is called an obstruction, and it can cause severe abdominal pain and vomiting. Because GISTs are often fragile, they can sometimes rupture, which can lead to a hole (perforation) in the wall of the GI tract. This can also result in severe abdominal pain. Emergency surgery might be needed in these situations.

Other medical conditions apart from cancer can cause these symptoms. If you have these symptoms, especially if they last for more than a few days, you should see your doctor. A GIST is rare so they are more likely to be caused by something less serious, but it is always best to check.

Can gastrointestinal stromal tumors be found early?

At this time, no effective screening tests have been found for gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs), so routine testing of people without any symptoms is not recommended.

Many GISTs are found because of symptoms a person is having, but some GISTs may be found early by chance. Sometimes they are seen on an exam for another problem, like during colonoscopy to look for colon cancer. Rarely, a GIST may be seen when an imaging test, like a computed tomography (CT) scan or barium study, is done for another reason. Some GISTs may also be found incidentally (unexpectedly) during abdominal surgery for another problem.

GIST tumor diagnosis

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) are often found because a person is having signs or symptoms. Others are found during exams or tests for other problems. But these symptoms or initial tests aren’t usually enough to know for sure if a person has a GIST or another type of gastrointestinal (GI) tumor. If a gastrointestinal stromal tumor is suspected, you will need further tests to confirm the diagnosis.

Imaging tests

Imaging tests use x-rays, magnetic fields, or radioactive substances to create pictures of the inside of the body. Imaging tests may be done for a number of reasons, including:

- To help find out if a suspicious area might be cancer

- To learn how far cancer has spread

- To help determine if treatment has been effective

- To look for signs that the cancer has come back

Most people who have or might have a gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) will have one or more of these tests.

Barium x-rays

Barium x-rays are not used as much today as in the past. In many cases they are being replaced by endoscopy – where the doctor actually looks into your colon or stomach with a narrow fiber-optic scope (see below).

For these types of x-rays, a chalky liquid containing barium is used to coat the inner lining of the esophagus, stomach, and intestines. This makes abnormal areas of the lining easier to see on x-ray. These tests are sometimes used to diagnose gastrointestinal stromal tumors, but they can miss some small intestine tumors.

You will probably have to fast starting the night before the test. If the colon is being examined, you might need to take laxatives and/or enemas to clean out the bowel the night before or the morning of the exam.

Barium swallow: This is often the first test done if someone is having a problem swallowing. For this test, you drink a liquid containing barium to coat the inner lining of the esophagus. A series of x-rays is then taken over the next few minutes.

Upper GI series: This test is similar to the barium swallow, except that x-rays are taken after the barium has time to coat the stomach and the first part of the small intestine. To look for problems in the rest of the small intestine, more x-rays can be taken over the next few hours as the barium passes through. This is called a small bowel follow through.

Enteroclysis: This test is another way to look at the small intestine. A thin tube is passed through your mouth or nose, down your esophagus, and through your stomach into the start of the small intestine. Barium is sent through the tube, along with a substance that creates more air in the intestines, causing them to expand. Then x-rays are taken of the intestines. This test can give better images of the small intestine than a small bowel follow through, but it is also more uncomfortable.

Barium enema: This test (also known as a lower GI series) is used to look at the inner surface of the large intestine. For this test, the barium solution is given through a small, flexible tube inserted in the anus while you are lying on the x-ray table. When the colon is about half full of barium, you roll over so the barium spreads throughout the colon. For a regular barium enema, x-rays are then taken. After the barium is put in the colon, air may be blown in to help push the barium toward the wall of the colon and better coat the inner surface. Then x-rays are taken. This is called an air-contrast barium enema or double-contrast barium enema.

Computed tomography (CT) scan

A CT scan uses x-rays to make detailed, cross-sectional images of your body. Unlike a regular x-ray, a CT scan creates detailed images of the soft tissues in the body.

CT scans can be useful in patients who have (or might have) GISTs to find the location and size of a tumor, as well as to see if it has spread into the abdomen or the liver.

In some cases, CT scans can also be used to guide a biopsy needle precisely into a suspected cancer. However, this can be risky if the tumor might be a GIST (because of the risk of bleeding and a possible increased risk of tumor spread), so these types of biopsies are usually done only if the result might affect the decision on treatment. See the biopsy information below.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan

Like CT scans, MRI scans show detailed images of soft tissues in the body. But MRI scans use radio waves and strong magnets instead of x-rays.

MRI scans can sometimes be useful in people with GISTs to help find the extent of the cancer in the abdomen, but usually CT scans are enough. MRIs can also be used to look for cancer that might havecome back (recurred) or spread (metastasized) to distant organs, particularly in the brain or spine.

Positron emission tomography (PET) scan

For a PET scan, you are injected with a slightly radioactive form of sugar, which collects mainly in cancer cells. A special camera is then used to create a picture of areas of radioactivity in the body. The picture is not detailed like a CT or MRI scan, but a PET scan can look for possible areas of cancer spread in all areas of the body at once.

Some newer machines can do both a PET and CT scan at the same time (PET/CT scan). This lets the doctor see areas that “light up” on the PET scan in more detail.

PET scans can be useful for looking at GISTs, especially if the results of CT or MRI scans aren’t clear. This test can also be used to look for possible areas of cancer spread to help determine if surgery is an option.

PET scans can also be helpful in finding out if a drug treatment is working, as they can often give an answer quicker than CT or MRI scans. The scan is usually obtained about 4 weeks after starting the medicine. If the drug is working, the tumor will stop taking up the radioactive sugar. If the tumor still takes up the sugar, your doctor may decide to change your drug treatment.

Endoscopy

For these tests, the doctor puts a flexible lighted tube (endoscope) with a tiny video camera on the end into the body to see the inner lining of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. If abnormal areas are found, small pieces can be biopsied (removed) through the endoscope. The biopsy samples can be looked at under the microscope to find out if they contain cancer and if so, what kind of cancer it is.

GISTs are often below the surface (mucosa) of the inner lining of the gastrointestinal tract. This can make them harder to see with endoscopy than more common gastrointestinal tract tumors, which typically start in the mucosa. The doctor may see only a bulge under the normally smooth surface if a GIST is present. GISTs that are below the mucosa are also harder to biopsy through the endoscope. This is one reason that many GISTs are not diagnosed before surgery.

If the tumor breaks through the inner lining of the gastrointestinal tract and is easy to see on endoscopy, there is a greater chance that the GIST is cancerous (malignant).

Upper endoscopy

Upper endoscopy is also known as esophagogastroduodenoscopy. For this procedure, an endoscope is passed through the mouth and down the throat to look at the inner lining of the esophagus, stomach, and first part of the small intestine. Biopsy samples may be taken from any abnormal areas.

Upper endoscopy can be done in a hospital, in an outpatient surgery center, or in a doctor’s office. You are typically given medicine through an intravenous (IV) line to make you sleepy before the exam. The exam itself usually takes 10 to 20 minutes, but it might take longer if a tumor is seen or if biopsy samples are taken. If medicine is given to make you sleepy, you will need someone you know to drive you home (not just a cab or rideshare service).

Colonoscopy (lower endoscopy)

For this test, a type of endoscope known as a colonoscope is inserted through the anus and up into the colon. This lets the doctor look at the inner lining of the rectum and colon and to take biopsy samples from any abnormal areas.

To get a good look at the inside of the colon, it must be cleaned out before the test. Your doctor will give you specific instructions. You might need to follow a special diet for a day or more before the test. You will also likely have to drink a large amount of a liquid laxative the evening before, which means you will spend a lot of time in the bathroom.

A colonoscopy can be done in a hospital, in an outpatient surgery center, or in a doctor’s office. You will be given intravenous (IV) medicine to make you feel relaxed and sleepy during the procedure. The exam typically takes 15 to 30 minutes, but it can take longer if a tumor is seen and/or a biopsy taken. Because medicine is given to make you sleepy, you will need someone you know to drive you home (not just a cab or rideshare service).

Capsule endoscopy

Unfortunately, neither upper endoscopy nor colonoscopy can reach all areas of the small intestine. Capsule endoscopy is one way to look at the small intestine.

This procedure does not actually use an endoscope. Instead, you swallow a capsule (about the size of a large vitamin pill) that contains a light source and a very small camera. Like any other pill, the capsule goes through the stomach and into the small intestine. As it travels through the intestine (usually over about 8 hours), it takes thousands of pictures. These images are transmitted electronically to a device worn around your waist. The pictures can then be downloaded onto a computer, where the doctor can view them as a video. The capsule passes out of the body during a normal bowel movement and is discarded.

This test requires no sedation – you can just continue normal daily activities as the capsule travels through the gastrointestinal tract. This technique is fairly new, and the best ways to use it are still being studied. One disadvantage is that any abnormal areas seen can’t be biopsied during the test.

Double balloon enteroscopy

This is another way to look at the small intestine. The small intestine is too long and has too many curves to be examined well with regular endoscopy. But this method gets around these problems by using a special endoscope that is made of 2 tubes, one inside the other.

You are given intravenous (IV) medicine to help you relax, or even general anesthesia (so that you are asleep). The endoscope is then inserted either through the mouth or the anus, depending on if there is a specific part of the small intestine to be examined.

Once inside the small intestine, the inner tube, which has the camera on the end, is advanced forward about a foot as the doctor looks at the lining of the intestine. Then a balloon on the end of the endoscope is inflated to anchor it. The outer tube is then pushed forward to near the end of the inner tube and is anchored in place with a second balloon. The first balloon is deflated and the endoscope is advanced again. This process is repeated over and over, letting the doctor see the intestine a foot at a time. The test can take hours to complete.

This test may be done along with capsule endoscopy. The main advantage of this test over capsule endoscopy is that the doctor can take a biopsy if something abnormal is seen. Like other forms of endoscopy, because you are given medicine to make you sleepy for the procedure, someone you know will need to drive you home (not just a cab or rideshare service).

Endoscopic ultrasound

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) is a type of imaging test that uses an endoscope. Ultrasound uses sound waves to take pictures of parts of the body. For most ultrasound exams, a wand-like probe (called a transducer) is placed on the skin. The probe gives off sound waves and detects the pattern of echoes that come back.

For an endoscopic ultrasound (EUS), the ultrasound probe is on the tip of an endoscope. This allows the probe to be placed very close to (or on top of) a tumor in the wall of the gastrointestinal tract. Like a regular ultrasound, the probe gives off sound waves and then detects the echoes that bounce back. A computer then translates the echoes into an image of the area being looked at.

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) can be used to find the precise location of the GIST and to determine its size. It is useful in finding out how deeply a tumor has grown into the wall of the gastrointestinal tract. The test can also help show if the tumor has spread to nearby lymph nodes or has started growing into other tissues nearby. In some cases it may be used to help guide a biopsy (see below).

You are typically given medicine before this procedure to make you sleepy. Because of this, you need to have someone you know drive you home (not just a cab or rideshare service).

Biopsy

Even if something abnormal is seen on an imaging test such as a barium x-ray or CT scan, these tests often cannot tell if the abnormal area is a GIST, some other type of tumor (benign or cancerous), or some other condition (like an infection). The only way to know what it is for sure is to remove cells from the area. This procedure is called a biopsy. The cells are then sent to a lab, where a doctor called a pathologist looks at them under a microscope and might do other tests on them.

Not everyone who has a tumor that might be a GIST needs a biopsy before treatment. If the doctor suspects a tumor may be a GIST, biopsies are usually done only if they will help determine treatment options. GISTs are often fragile tumors that tend to break apart and bleed easily. Any biopsy must be done very carefully, because of the risk that the biopsy might cause bleeding or possibly increase the risk of cancer spreading.

There are several ways to biopsy a gastrointestinal tract tumor.

Endoscopic biopsy

Biopsy samples can be obtained through an endoscope. When a tumor is found, the doctor can insert biopsy forceps (pincers or tongs) through the tube to take a small sample of the tumor.

Even though the sample will be very small, doctors can often make an accurate diagnosis. However, with GISTs, sometimes the biopsy forceps can’t go deep enough to reach the tumor because it’s underneath the inner lining of the stomach or intestine.

Bleeding from a GIST after a biopsy is rare, but it can be a serious problem. If this occurs, doctors can sometimes inject drugs into the tumor through an endoscope to constrict blood vessels and stop the bleeding.

Needle biopsy

Sometimes, a biopsy is done using a thin, hollow needle to remove pieces of the area. The most common way to do this is during an endoscopic ultrasound (described above). The doctor uses the ultrasound image to guide a needle on the tip of the endoscope into the tumor.

Less often, the doctor may place a needle through the skin and into the tumor while guided by an imaging test such as a CT scan.

Surgical biopsy

If a sample can’t be obtained from an endoscopic or needle biopsy, or if the result of a biopsy wouldn’t affect treatment options, your doctor might recommend waiting until surgery to remove the tumor to get a sample of it.

If the surgery is done through a large cut (incision) in the abdomen, it is called a laparotomy. Sometimes the tumor can be sampled (or small tumors can be removed) using a thin, lighted tube called a laparoscope, which lets the surgeon see inside the belly through a small incision. The surgeon can then sample (or remove) the tumor using long, thin surgical tools that are passed through other small incisions in the abdomen. This is known as laparoscopic or keyhole surgery.

Lab tests of biopsy samples

Once tumor samples are obtained, a pathologist looks at them under a microscope. The pathologist might be able to tell that a tumor is most likely a GIST just by looking at the cells. But sometimes further lab tests might be needed to be sure.

Immunohistochemistry: For this lab test, a part of the sample is treated with man-made antibodies that will attach only to a certain protein. The antibodies cause color changes if the protein is present, which can be seen under a microscope.

Some of the proteins most often tested for if GIST is suspected are KIT (also known as CD117) and DOG1. Most GIST cells have these proteins, but cells of most other types of cancer do not, so tests for these proteins can help tell whether a gastrointestinal tumor is a GIST or not. Other proteins, such as PDGFRA, might be tested for as well.

Molecular genetic testing: If the doctor is still unsure if the tumor is a GIST, testing might be done to look for mutations in the KIT or PDGFRA genes themselves, as most GIST cells have mutations in one or the other. Less often, tests might be done to look for changes in other genes, such as SDH.

Mitotic rate: If a GIST is diagnosed, the doctor will also look at the cancer cells in the sample to see how many of them are actively dividing into new cells. This is known as the mitotic rate. A low mitotic rate means the cancer cells are growing and dividing slowly, while a high rate means they are growing quickly. The mitotic rate is an important part of the stage of the cancer.

Blood tests

Your doctor may order some blood tests if he or she thinks you may have a GIST.

There are no blood tests that can tell for sure if a person has a GIST. But blood tests can sometimes point to a possible tumor (or to its spread). For example, a complete blood count (CBC) can tell if you have a low red blood cell count (that is, if you are anemic). Some people with GIST may become anemic because of bleeding from the tumor. Abnormal liver function tests may mean that the GIST has spread to your liver.

Blood tests are also done to check your overall health before you have surgery or while you get other treatments such as targeted therapy.

Gastrointestinal stromal tumor stages

After someone is diagnosed with GIST tumor, doctors will try to figure out if it has spread, and if so, how far. This process is called staging. The stage of a cancer describes how much cancer is in the body. It helps determine how serious the cancer is and how best to treat it. Doctors also use a cancer’s stage when talking about survival statistics.

The stages for gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) range from stages I (1) through IV (4). As a rule, the lower the number, the less the cancer has spread. A higher number, such as stage IV, means cancer has spread more. And within a stage, an earlier letter means a lower stage. Although each person’s cancer experience is unique, cancers with similar stages tend to have a similar outlook and are often treated in much the same way.

The staging system most often used for GIST tumors is the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) TNM system, which is based on 4 key pieces of information:

- The extent of the tumor (T): How large is the cancer?

- The spread to nearby lymph nodes (N): Has the cancer spread to nearby lymph nodes?

- The spread (metastasis) to distant sites (M): Has the cancer spread to distant organs such as the liver?

- The mitotic rate is a lab test measurement of how fast the cancer cells are growing and dividing. It is described as either low or high. A low mitotic rate predicts a better outcome.

Numbers or letters after T, N, and M provide more details about each of these factors. Higher numbers mean the cancer is more advanced. Once a person’s T, N, and M categories have been determined, this information is combined in a process called stage grouping to assign an overall stage. The stage grouping for GIST tumors depends on where the tumor starts:

- The stomach or the omentum (the omentum is an apron-like layer of fatty tissue that hangs over the organs in the abdomen.) OR

- The small intestine, esophagus, colon, rectum, or peritoneum. (The peritoneum is a layer of tissue that lines the organs and walls of the abdomen. Tumors in these locations are more likely to grow quickly compared to GISTs that start in the stomach or omentum.)

The staging system in the table below uses the pathologic stage (also called the surgical stage). It is determined by examining tissue removed during an operation. Sometimes, if surgery is not possible right away or at all, the cancer will be given a clinical stage instead. This is based on the results of a physical exam, biopsy, and imaging tests. The clinical stage will be used to help plan treatment. Sometimes, though, the cancer has spread further than the clinical stage estimates, and might not predict the patient’s outlook as accurately as a pathologic stage.

The system described below is the most recent American Joint Committee on Cancer system, effective January 2018. Cancer staging can be complex, so ask your doctor to explain it to you in a way you understand.

Table 1. GIST that starts in the stomach or the omentum stages

| American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) stage | Stage grouping | Mitotic rate | Stage description* |

| IA | T1 or T2 N0 M0 | Low | The cancer is:

It has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant sites (M0). The mitotic rate is low. |

| IB | T3 N0 M0 | Low | The cancer is larger than 5 cm (2 inches) but not more than 10 cm (T3). It has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant sites (M0). The mitotic rate is low. |

| II | T1 N0 M0 | High | The cancer is 2 cm or smaller (T1). It has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant sites (M0). The mitotic rate is high. |

| OR | |||

| T2 N0 M0 | High | The cancer is larger than 2 cm but not more than 5 cm (T2). It has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant sites (M0). The mitotic rate is high. | |

| OR | |||

| T4 N0 M0 | Low | The cancer is larger than 10 cm (T4). It has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant sites (M0). The mitotic rate is low. | |

| IIIA

| T3 N0 M0 | High | The cancer is larger than 5 cm (2 inches) but not more than 10 cm(T3). It has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant sites (M0). The mitotic rate is high. |

| IIIB | T4 N0 M0 | High | The cancer is larger than 10 cm (T4). It has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant sites (M0). The mitotic rate is high. |

| IV | Any T N1 M0 | Any rate | The cancer is any size (Any T) AND it has spread to nearby lymph nodes (N1). It has not spread to distant sites (M0). The cancer can have any mitotic rate. |

| OR | |||

| Any T Any N M1 | Any rate | The cancer is any size (Any T) AND it might or might not have spread to nearby lymph nodes (Any N). It has spread to distant sites such as the liver(M1). The cancer can have any mitotic rate. | |

Footnote:

*The following additional categories are not listed in the table above:

- TX: Main tumor cannot be assessed due to lack of information.

- T0: No evidence of a primary tumor.

- NX: Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed due to lack of information.

Table 2. GIST of the small intestine, esophagus, colon, rectum, or peritoneum

| American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) stage | Stage grouping | Mitotic rate | Stage description* |

| I | T1 or T2 N0 M0 | Low | The cancer is:

It has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant sites (M0). The mitotic rate is low. |

| II | T3 N0 M0 | Low | The cancer is larger than 5 cm (2 inches) but not more than 10 cm(T3). It has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant sites (M0). The mitotic rate is low. |

| IIIA | T1 N0 M0 | High | The cancer is 2 cm or smaller (T1). It has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant sites (M0). The mitotic rate is high. |

| OR | |||

| T4 N0 M0 | Low | The cancer is larger than 10 cm (T4). It has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant sites (M0). The mitotic rate is low. | |

| IIIB | T2 N0 M0 | High | The cancer is larger than 2 cm but not more than 5 cm (T2). It has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant sites (M0). The mitotic rate is high. |

| OR | |||

| T3 N0 M0 | High | The cancer is larger than 5 cm (2 inches) but not more than 10cm (T3). It has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant sites (M0). The mitotic rate is high. | |

| OR | |||

| T4 N0 M0 | High | The cancer is larger than 10 cm (T4). It has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant sites (M0). The mitotic rate is high. | |

| IV | Any T N1 M0 | Any rate | The cancer is any size (Any T) AND it has spread to nearby lymph nodes (N1). It has not spread to distant sites (M0). The cancer can have any mitotic rate. |

| OR | |||

| Any T Any N M1 | Any rate | The cancer is any size (Any T) AND it might or might not have spread to nearby lymph nodes (Any N). It has spread to distant sites such as the liver(M1). The cancer can have any mitotic rate. | |

Footnote:

*The following additional categories are not listed in the table above:

- TX: Main tumor cannot be assessed due to lack of information.

- T0: No evidence of a primary tumor.

- NX: Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed due to lack of information.

Resectable versus unresectable tumors

The American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging system gives a detailed summary of how far a GIST has spread. But for treatment purposes, doctors are often more concerned about whether the tumor can be removed (resected) completely with surgery.

Whether or not a tumor is resectable depends on its size and location, if it has spread to other parts of the body, and if a person is healthy enough for surgery:

- Tumors that can clearly be removed without causing major health problems are defined as resectable.

- Tumors that can’t be removed completely (because they have spread or for other reasons) are described as unresectable.

- In some cases, doctors may describe a tumor as marginally resectable or borderline resectable if it’s not clear if it can be removed completely.

If a tumor is considered unresectable or marginally resectable when it is first found, treatments such as targeted therapy may be used first to try to shrink the tumor enough to make it resectable.

GIST tumor treatment

There are different types of treatment for patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Some treatments are standard (the currently used treatment), and some are being tested in clinical trials. A treatment clinical trial is a research study meant to help improve current treatments or obtain information on new treatments for patients with cancer. When clinical trials show that a new treatment is better than the standard treatment, the new treatment may become the standard treatment. Patients may want to think about taking part in a clinical trial. Some clinical trials are open only to patients who have not started treatment.

Four types of standard treatment are used:

Surgery

Surgery is usually the main treatment for GIST. If the GIST has not spread and is in a place where surgery can be safely done, the tumor and some of the tissue around it may be removed. Sometimes surgery is done using a laparoscope (a thin, lighted tube) to see inside the body. Small incisions (cuts) are made in the wall of the abdomen and a laparoscope is inserted into one of the incisions. Instruments may be inserted through the same incision or through other incisions to remove organs or tissues.

Your surgeon aims to remove as much of the cancer as possible with a border of healthy tissue (clear margin) around it. Having a border of healthy tissue without any cancer cells is important as it lowers the risk of the cancer coming back.

Surgery might cure a smaller GIST. But it might not be possible for a surgeon to remove a larger GIST completely.

GIST can sometimes spread to other parts of the body. This spread is called a secondary or metastases. In some situations, it might be possible for a surgeon to remove these secondaries.

GIST in the stomach means your surgeon might need to remove all or part of your stomach. They may also need to remove your spleen. Surgery to the stomach is a big operation and it will take some time to adjust your eating afterwards. You will probably have to eat small, frequent meals (about two hourly) for quite a long time after the operation.

Targeted cancer drugs

Targeted cancer drugs also known as targeted therapy is a type of treatment that uses drugs or other substances to identify and attack specific cancer cells without harming normal cells.

Tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) are targeted therapy drugs that block signals needed for tumors to grow. They block chemical messengers (enzymes) called tyrosine kinases. Tyrosine kinases help to send growth signals in cells, so blocking them stops the cell growing and dividing. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors may be used to treat GISTs that cannot be removed by surgery or to shrink GISTs so they become small enough to be removed by surgery. Imatinib mesylate and sunitinib are two tyrosine kinase inhibitors used to treat GISTs. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors are sometimes given for as long as the tumor does not grow and serious side effects do not occur.

Imatinib (Glivec)

You might have imatinib to treat a GIST that can’t be completely removed with surgery, or which has spread before surgery.

Some people with GIST have a higher risk of their cancer coming back after surgery. This is called a high risk GIST. Imatinib can help to reduce the chances of the GIST coming back. So in this situation, your doctor may recommend you take imatinib for up to 3 years after your operation.

You may also have imatinib to shrink a GIST before surgery, so that your surgeon can remove it more easily. Sometimes a surgeon can completely remove a GIST after treatment with imatinib.

Protein testing for imatinib

Your doctor needs a sample of your GIST to carry our protein testing. This sample might be from when you had a biopsy to diagnose GIST, or an operation to remove the GIST. The cells are tested to see if they have a receptor on their surface called CD117.

This CD117 protein is made by a gene called c-kit. A fault in this gene causes the c-kit gene to make too much CD117 protein. Most GISTs have c-kit gene mutations.

If the GIST cells are CD117 positive, imatinib is likely to work very well. But it can work even for GISTs that are CD117 negative.

Sunitinib (Sutent)

Your doctor might recommend that you have sunitinib (Sutent) in one of the following situations:

- imatinib has stopped working

- you have had severe side effects with imatinib treatment

You must have GIST that cannot be completely removed or has spread.

Regorafenib (Stivarga)

Regorafenib (Stivarga) is used to treat advanced GIST. Your doctor might recommend regorafenib if you have had treatment with imatinib and sunitinib and these drugs:

- have not worked

- or caused bad side effects

Advanced GIST means you cannot have surgery to remove the GIST, or it has spread. You must be fairly fit and well to have this drug.

Watchful waiting

Watchful waiting is closely monitoring a patient’s condition without giving any treatment until signs or symptoms appear or change.

Supportive care

If a GIST gets worse during treatment or there are side effects, supportive care is usually given. The goal of supportive care is to prevent or treat the symptoms of a disease, side effects caused by treatment, and psychological, social, and spiritual problems related to a disease or its treatment. Supportive care helps improve the quality of life of patients who have a serious or life-threatening disease. Radiation therapy is sometimes given as supportive care to relieve pain in patients with large tumors that have spread.

Clinical trials

For some patients, taking part in a clinical trial may be the best treatment choice. Clinical trials are part of the cancer research process. Clinical trials are done to find out if new cancer treatments are safe and effective or better than the standard treatment.

Many of today’s standard treatments for cancer are based on earlier clinical trials. Patients who take part in a clinical trial may receive the standard treatment or be among the first to receive a new treatment.

Patients who take part in clinical trials also help improve the way cancer will be treated in the future. Even when clinical trials do not lead to effective new treatments, they often answer important questions and help move research forward.

Information about clinical trials is available from the National Cancer Institute website (https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/treatment/clinical-trials/search). Use the National Cancer Institute clinical trial search to find National Cancer Institute-supported cancer clinical trials that are accepting patients. You can search for trials based on the type of cancer, the age of the patient, and where the trials are being done.

GIST tumor survival rates

Survival rates can give you an idea of what percentage of people with the same type and stage of cancer are still alive a certain amount of time (usually 5 years) after they were diagnosed. They can’t tell you how long you will live, but they may help give you a better understanding of how likely it is that your treatment will be successful.

Keep in mind that survival rates are estimates and are often based on previous outcomes of large numbers of people who had a specific cancer, but they can’t predict what will happen in any particular person’s case. These statistics can be confusing and may lead you to have more questions. Talk with your doctor about how these numbers may apply to you, as he or she is familiar with your situation.

A relative survival rate compares people with the same type and stage of gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) to people in the overall population. For example, if the 5-year relative survival rate for a specific stage of GIST is 94%, it means that people who have that cancer are, on average, about 94% as likely as people who don’t have that cancer to live for at least 5 years after being diagnosed.

Table 3. GIST tumors 5-year relative survival rates (Based on people diagnosed with GIST between 2008 and 2014.)

| Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Stage | 5-Year Relative Survival Rate |

| Localized | 94% |

| Regional | 83% |

| Distant | 52% |

| All SEER stages combined | 83% |

Footnote:

- Localized: The cancer is limited to the organ where it started.

- Regional: The cancer has grown into nearby structures or spread to nearby lymph nodes.

- Distant: The cancers has spread to distant parts of the body such as the liver.

These numbers apply only to the stage of the cancer when it is first diagnosed. They do not apply later on if the cancer grows, spreads, or comes back after treatment.

These numbers don’t take everything into account. Survival rates are grouped based on how far the cancer has spread, but your age, overall health, cancer resectability, how well the cancer responds to treatment, and other factors can also affect your outlook.

People now being diagnosed with GIST may have a better outlook than these numbers show. Treatments improve over time, and these numbers are based on people who were diagnosed and treated at least five years earlier.

[Source 1 ]- Survival Rates for Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/gastrointestinal-stromal-tumor/detection-diagnosis-staging/survival-rates.html[↩]