What is H. pylori

H. pylori is short for Helicobacter pylori, is a Gram negative, spiral-shaped bacteria that is known to be a major cause of peptic ulcer disease (ulcers in the lining of your stomach or your duodenum, the first part of your small intestine). H. pylori infection is associated with an increased risk of developing peptic ulcer disease, chronic gastritis, gastric (stomach) cancer – gastric B-cell lymphoma of mucosal-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT lymphoma), and invasive gastric adenocarcinoma 1. H. pylori colonizes half of the world’s human population 2. H. pylori typically colonizes the human stomach for years or even decades, often without adverse consequences 3. Most people don’t realize they have H. pylori infection, because they never get sick from it. If you develop signs and symptoms of a peptic ulcer (ulcers in the lining of your stomach or your duodenum, the first part of your small intestine), your doctor will probably test you for H. pylori infection. If you have H. pylori infection, it can be treated with antibiotics.

H. pylori is a common human pathogen that has existed in the stomach since as early as 60,000 years ago 4.

H. pylori is very common, especially in developing countries. The bacteria are present in (colonize) the stomachs and intestines of as many as 50% of the world’s population. Most of those affected will never have any symptoms, but the presence of H. pylori increases the risk of developing ulcers (peptic ulcer disease), chronic gastritis, and gastric (stomach) cancer. The bacteria decrease the stomach’s ability to produce mucus, making the stomach prone to acid damage and peptic ulcers.

The Maastricht V/Florence Consensus, the Kyoto Global Consensus and the Toronto Consensus reports have emphasized the importance of H. pylori in the pathogenesis of gastric diseases and recommended the eradication of H. pylori for preventing gastric cancer 5. Additionally, H. pylori eradication may rapidly decrease active inflammation in the gastric mucosa 6, prevent progression toward precancerous lesions 7 and reverse gastric atrophy before the development of intestinal metaplasia 8. Undoubtedly, the earliest possible eradication of H. pylori is highly beneficial.

Treatment usually involves a combination of antibiotics and drugs to reduce the amount of stomach acid produced, such as proton pump inhibitors and histamine receptor blockers, as well as a bismuth preparation, such as Pepto-Bismol®, taken for several weeks.

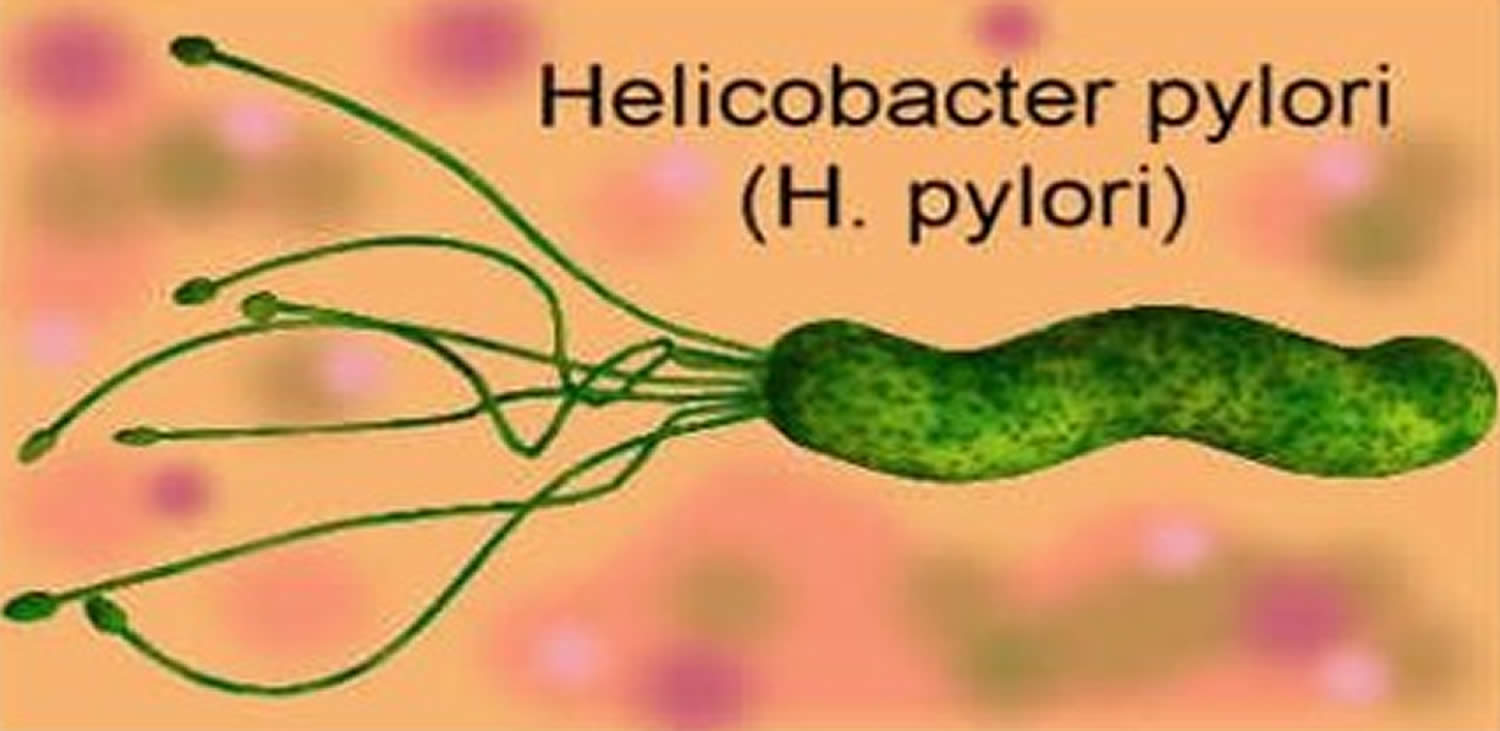

Figure 1. H. pylori (Helicobacter pylori) bacteria

Footnote: High resolution scanning electron micrograph of H. pylori in contact with human gastric epithelial cells. Magnification bar indicates 1 μm. H. pylori virulence factors including flagella (black arrows) and cag-T4SS pili (white arrows) are present on the bacterial cell surface during host-pathogen interaction. Flagella aid in cell motility through the mucus layer to penetrate host tissues. The cag-T4SS pili induce proinflammatory and oncogenic cellular responses.

[Source 9]H. pylori complications

Complications associated with H. pylori infection include:

- Ulcers. H. pylori can damage the protective lining of your stomach and small intestine. This can allow stomach acid to create an open sore (ulcer). About 10 percent of people with H. pylori will develop an ulcer.

- Inflammation of the stomach lining. H. pylori infection can irritate your stomach, causing inflammation (gastritis).

- Stomach cancer. H. pylori infection is a strong risk factor for certain types of stomach cancer.

Does everyone with H. pylori get ulcers?

No, many people have evidence of infection but have no symptoms of ulcerative disease. The reason why some people with H. pylori infections develop peptic ulcers and others do not is not yet understood.

Should everyone be tested for H. pylori?

Since the infection is very common and most people do not ever get ulcers, testing is generally only recommended for those who have signs and symptoms.

Does everyone treated for H. pylori get better?

The majority of people who successfully complete the combination antibiotic therapy get rid of these bacteria from their GI tract. However, resistance to some of the antibiotics may occur and, therefore, the bacteria may continue to multiply in spite of appropriate therapy.

Can I get another H. pylori infection after my treatment?

Treatment does not make a person immune, so there is always the potential for becoming infected again.

Is H. pylori contagious?

Yes, however the exact means of acquiring H. pylori is not always clear 10. Helicobacter pylori infects at least 50% of the world’s population 11. The H. pylori bacteria are believed to be transmitted by eating food or drinking water that has been contaminated with human fecal material, or possibly through contact with the stool, vomit, or saliva of an infected person. Exposure to family members with H. pylori seems to be the most likely opportunity for transmission. Person-to-person transmission is most commonly implicated with fecal/oral, oral/oral, or gastric/oral pathways 12; each has supportive biologic as well as epidemiologic evidence.

H. pylori infection symptoms

Most people with H. pylori infection will never have any signs or symptoms. It’s not clear why this is, but some people may be born with more resistance to the harmful effects of H. pylori.

When signs or symptoms do occur with H. pylori infection, they may include:

- An ache or burning pain in your abdomen

- Abdominal pain that’s worse when your stomach is empty

- Nausea

- Loss of appetite

- Frequent burping

- Bloating

- Unintentional weight loss

People can have gastrointestinal pain for many reasons; an ulcer caused by H. pylori is only one of them. Make an appointment with your doctor if you notice any persistent signs and symptoms that worry you. Seek immediate medical help if you experience:

- Severe or persistent abdominal pain

- Difficulty swallowing

- Bloody or black tarry stools

- Bloody or black vomit or vomit that looks like coffee grounds

How do you get H. pylori?

Helicobacter pylori infects at least 50% of the world’s population 11. Infection occurs in early life, before age 10 years 13. Because acute infection invariably passes undetected, however, the precise age of acquisition is unknown. In industrialized countries, infection rates are declining rapidly 14, but high rates of infection persist among disadvantaged and immigrant populations 15.

The mechanisms of H. pylori transmission are incompletely characterized and the exact means of acquiring H. pylori is not always clear 10. The H. pylori bacteria are believed to be transmitted by eating food or drinking water that has been contaminated with human fecal material, or possibly through contact with the stool, vomit, or saliva of an infected person. Exposure to family members with H. pylori seems to be the most likely opportunity for transmission. Person-to-person transmission is most commonly implicated with fecal/oral, oral/oral, or gastric/oral pathways 12; each has supportive biologic as well as epidemiologic evidence. Like many common gastrointestinal infections, infection is associated with conditions of crowding and poor hygiene 16 and with intrafamilial clustering 17. H. pylori organism has been recovered most reliably from vomitus and from stools during rapid gastrointestinal transit 18. These findings raise the hypothesis that gastroenteritis episodes provide the opportunity for H. pylori transmission.

In this prospective study 11 of H. pylori infection and household gastroenteritis within a US immigrant population, researchers estimated an annualized H. pylori incidence rate of 7%, including 21% among children <2 years of age. Exposure to H. pylori–infected persons with gastroenteritis, particularly with vomiting, increased risk for new infection, and three quarters of definite or probable new infections were attributable to exposure to H. pylori infection with gastroenteritis. These findings indicate that in US immigrant homes, H. pylori transmission occurs in young children during household episodes of gastroenteritis.

Exposure to an infected household member with vomiting was associated with a 6-fold greater risk for new infection, whereas exposure to diarrhea elevated, but not significantly, the risk for new infection. These findings are consistent with prior research that shows that H. pylori is recovered reliably from vomitus (up to 30,000 CFU/mL) and can also can be grown from aerosolized vomitus collected at short distances (<1.2 m) 19. Epidemiologic investigations also implicate vomitus as an effective vehicle for gastro-oral transmission 20. Although found in diarrheal stools 19, H. pylori is not reliably grown from normal stools 21. The association between H. pylori and gastroenteritis is thus similar to that of other enteric pathogens that can be transmitted by vomitus or aerosolized vomitus or by the fecal-oral route 22. Although scientists cannot exclude other mechanisms of transmission in these homes, exposure to vomitus in an infected contact explained >50% of all new infections and >70% of definite and probable new infections.

In experimental exposure, acute infection causes mild to moderate epigastric discomfort or dyspepsia in most study participants within 2 weeks, but symptoms are unlikely to be clinically detected 23. Although H. pylori–specific IgM antibodies may appear within 4 weeks, the frequency of this response is variable, particularly in children and when, as here, the time of infection is unknown 24. Researchers did not observe a pronounced difference in the frequency or distribution of symptoms associated with new infection, although vomiting tended to be more frequent among persons with definite or probable new infections. Although the relatively small numbers of new cases may have limited the power of this analysis, no symptom complex was identified that would permit differentiation of acute H. pylori infection from other enteric processes. Because researchers did not establish the specific etiologic agent of gastroenteritis episodes, further studies are needed to more fully address this question.

Half of new infections were in children <2 years of age, and 2 of 3 were identified by a single unconfirmed stool conversion. Although H. pylori infection is acquired in early childhood, age of acquisition has been difficult to establish because of known limitations of existing noninvasive tests in very young children. In a Bogalusa, Louisiana, birth cohort, for example, the highest seroconversion rate (2%) was seen in children 4–5 years of age 25. Although stool antigen and urea breath tests are considered more accurate 26, studies in very young children are still limited. When the urea breath test was used, an annualized conversion rate of 20% was observed in the US–Mexican binational Pasitos cohort of children followed up from birth to 2 years 27. If, as suggested by this and other studies 28, 29, acquisition with transient infection in early life often precedes persistent infection, rates of acquisition might be elevated when exposure to gastroenteritis is frequent. Rates of acquisition among children in homes at high risk may nonetheless be meaningful measures of transmission risk.

In summary, this study 11 corroborates the conclusion that gastroenteritis, particularly with vomiting, in an H. pylori–infected person is a primary cause of transmission of H. pylori in humans. As with other enteric infections such as hepatitis A, shigellosis, and cholera, H. pylori infection rates have decreased dramatically with improvements in sanitary infrastructure and household hygienic practices. Despite these trends, acquisition and infection are likely to remain prevalent in households with preexisting H. pylori infection, crowded living conditions, and frequent gastroenteritis.

H. pylori causes

The exact way H. pylori infects someone is still unknown. H. pylori bacteria may be passed from person to person through direct contact with saliva, vomit or fecal matter. H. pylori may also be spread through contaminated food or water.

Risk factors

H. pylori is often contracted in childhood. Risk factors for H. pylori infection are related to living conditions in your childhood, such as:

- Living in crowded conditions. You have a greater risk of H. pylori infection if you live in a home with many other people.

- Living without a reliable supply of clean water. Having a reliable supply of clean, running water helps reduce the risk of H. pylori.

- Living in a developing country. People living in developing countries, where crowded and unsanitary living conditions may be more common, have a higher risk of H. pylori infection.

- Living with someone who has an H. pylori infection. If someone you live with has H. pylori, you’re more likely to also have H. pylori.

H. pylori prevention

In areas of the world where H. pylori infection and its complications are common, doctors sometimes test healthy people for H. pylori. Whether there is a benefit to treating H. pylori when you have no signs or symptoms of infection is controversial among doctors.

If you’re concerned about H. pylori infection or think you may have a high risk of stomach cancer, talk to your doctor. Together you can decide whether you may benefit from H. pylori screening.

H. pylori test

H. pylori testing detects an infection of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract caused by the Helicobacter pylori bacteria and to evaluate the effectiveness of treatment.

There are several different types of H. pylori testing that can be performed. Some are less invasive than others.

The stool antigen test and urea breath test are recommended for the diagnosis of an H. pylori infection and for the evaluation of the effectiveness of treatment. These tests are the most frequently performed because they are fast and noninvasive. Endoscopy-related tests may also be performed to diagnose and evaluate H. pylori but are less frequently performed because they are invasive.

Noninvasive Without Endoscopy

- Stool antigen test – detection of H. pylori in a stool sample. As with the breath test, proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) and bismuth subsalicylate can affect the results of this test, so your doctor will ask you to stop taking them for two weeks before the test.

- Urea breath test – detection of labeled carbon dioxide in the breath after drinking a solution

- An antibody test using a blood sample is not recommended for routine diagnosis or for evaluation of treatment effectiveness. This test detects antibodies to the bacteria and will not distinguish between a present and previous infection. If the antibody test is negative, then it is unlikely that a person has had an H. pylori infection. If ordered and positive, results should be confirmed using a stool antigen or breath test.

| Stool/fecal antigen test | Detects the presence of H. pylori antigen in a stool sample |

| Urea breath test | A person drinks a liquid containing a low level of radioactive material that is harmless or a nonradioactive material. If H. pylori is present in the person’s gastrointestinal tract, the material will be broken down into “labeled” carbon dioxide gas that is expelled in the breath. |

| H. pylori antibody testing | Test not recommended for routine diagnosis or for evaluation of treatment effectiveness. Detects antibodies to the bacteria and will not distinguish previous infection from a current one. If test is negative, then it is unlikely that a person has had an H. pylori infection. If ordered and positive, results should be confirmed using stool antigen or breath test. |

Invasive With Endoscopy and Tissue Biopsy

Invasive tests using an endoscopy procedure are less frequently performed than noninvasive tests because they require a tissue biopsy collection. Tests include:

- Histology – examination of tissue under a microscope

- Rapid urease testing – detects urease, an enzyme produced by H. pylori

- Culture – growing H. pylori in/on a nutrient solution

| Histology | Tissue examined under a microscope by a pathologist, who will look for H. pylori bacteria and any other signs of disease that may explain a person’s symptoms. |

| Rapid urease testing | H. pylori produces urease, an enzyme that allows it to survive in the acidic environment of the stomach. The laboratory test can detect urease in the tissue sample. |

| Culture | The bacteria are grown on/in a nutrient media; results can take several weeks. This test is necessary if the health practitioner wants to evaluate which antibiotic will likely cure the infection. |

| PCR (polymerase chain reaction) | Fragments of H. pylori DNA are amplified and used to detect the bacteria; primarily used in a research setting. |

When is H. pylori test ordered?

Since all patients with a positive test of active infection with H. pylori should be offered treatment, the critical issue is which patients should be tested for the infection.

H. pylori testing may be ordered when someone is experiencing gastrointestinal pain and has signs and symptoms of an ulcer. Some of these may include:

- Abdominal pain that comes and goes over time

- Unexplained weight loss

- Indigestion

- Feeling of fullness or bloating

- Nausea

- Belching

Some people may have more serious signs and symptoms that require immediate medical attention, including sharp, sudden, persistent stomach pain, bloody or black stools, or bloody vomit or vomit that looks like coffee grounds.

H. pylori testing may also be ordered when a person has completed a regimen of prescribed antibiotics to confirm that the H. pylori bacteria have been eliminated. A follow-up test is not performed on every person, however.

American College of Gastroenterology Recommendations 30:

- All patients with active peptic ulcer disease (ulcers in the lining of your stomach or your duodenum, the first part of your small intestine), a past history of peptic ulcer disease (unless previous cure of H. pylori infection has been documented), low-grade gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma, or a history of endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer should be tested for H. pylori infection. Those who test positive should be offered treatment for the infection.

- In patients with uninvestigated dyspepsia who are under the age of 60 years and without alarm features, non-endoscopic testing for H. pylori infection is a consideration. Those who test positive should be offered eradication therapy.

- When upper endoscopy is undertaken in patients with dyspepsia, gastric biopsies should be taken to evaluate for H. pylori infection. Infected patients should be offered eradication therapy.

- Patients with typical symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) who do not have a history of peptic ulcer disease need not be tested for H. pylori infection. However, for those who are tested and found to be infected, treatment should be offered, acknowledging that effects on GERD symptoms are unpredictable.

- In patients taking long-term low-dose aspirin, testing for H. pylori infection could be considered to reduce the risk of ulcer bleeding. Those who test positive should be offered eradication therapy.

- Patients initiating chronic treatment with a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) should be tested for H. pylori infection. Those who test positive should be offered eradication therapy. The benefits of testing and treating H. pylori in patients already taking NSAIDs remains unclear.

- Patients with unexplained iron deficiency anemia despite an appropriate evaluation should be tested for H. pylori infection. Those who test positive should be offered eradication therapy.

- Adults with idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) should be tested for H. pylori infection. Those who test positive should be offered eradication therapy.

- There is insufficient evidence to support routine testing and treating of H. pylori in asymptomatic individuals with a family history of gastric cancer or patients with lymphocytic gastritis, hyperplastic gastric polyps and hyperemesis gravidarum.

How is the sample collected for testing?

The sample collected depends on the test ordered. For the urea breath test, a breath sample is collected and then the person is given a liquid to drink. Another breath sample is collected at a timed interval. For the stool antigen test, a stool sample is collected in a clean container.

A more invasive test will require a procedure called an endoscopy, which involves putting a thin tube with a tiny camera on the end down the throat into the stomach. This allows for visualization of the stomach lining as well as the ability to take a small piece of tissue (a biopsy) from the lining for examination.

Is any test preparation needed to ensure the quality of the sample?

For the urea breath test, you may be instructed to refrain from taking certain medications:

- Four weeks before the test, do not take any antibiotics or oral bismuth subsalicylate (Pepto Bismol®).

- Two weeks before the test, do not take any prescription or over-the-counter proton pump inhibitors, such as omeprazole, lansoprazole, or esomeprazole.

- One hour before the test, do not eat or drink anything (including water).

If submitting a stool sample or having a tissue biopsy collected, it may be necessary to refrain from taking any antibiotics, antacids, or bismuth treatments for 14 days prior to the test.

If undergoing endoscopy, fasting after midnight on the night prior to the procedure may be required.

If someone uses antacids within the week prior to testing, the rapid urease test may be falsely negative. Antimicrobials, proton pump inhibitors, and bismuth preparations may interfere with all but the blood antibody test.

H. pylori breath test

During a H. pylori urea breath test, a person swallows a pill, drinks a liquid or eat or pudding containing a low level of radioactive tagged carbon molecules that is harmless or a nonradioactive material. If H. pylori is present in the person’s gastrointestinal tract, the material will be broken down in your stomach into “labeled” carbon dioxide gas that is expelled in your breath. You exhale into a bag, and your doctor uses a special device to detect the carbon molecules.

Acid-suppressing drugs known as proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), bismuth subsalicylate (Pepto-Bismol) and antibiotics can interfere with the accuracy of this test. Your doctor will ask you to stop taking those medications for a week or two weeks before you have the test.

The urea breath test is not typically recommended for young children. In children, the preferred test would be the stool antigen test.

What does the H. pylori test result mean?

A positive H. pylori stool antigen, breath test, or biopsy indicates that a person’s gastrointestinal pain is likely caused by a peptic ulcer due to these bacteria. Treatment with a combination of antibiotics and other medications will be prescribed to kill the bacteria and stop the pain and the ulceration.

A positive blood test for H. pylori antibody may indicate a current or previous infection. A different test for H. pylori such as the breath test may need to be done as follow up to determine whether the infection is a current one.

A negative test result means that it is unlikely that the individual has an H. pylori infection and their signs and symptoms may be due to another cause. However, if symptoms persist, additional testing may be done, including the more invasive tissue biopsy, to more conclusively rule out infection.

Why is the blood test for H. pylori antibodies not recommended?

The American Gastroenterology Association, the American College of Gastroenterologists, the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Society for Microbiology do not recommend the antibody blood test for routine use in diagnosing an H. pylori infection or evaluating its treatment as the test cannot distinguish between a present and previous infection. However, some health practitioners still use this test. If the blood test is negative, then it is unlikely that the person has had an H. pylori infection. If it is positive, then the presence of a current H. pylori infection should be confirmed with a stool antigen or breath test.

H. pylori treatment

H. pylori infections are usually treated with at least two different antibiotics at once, to help prevent the bacteria from developing a resistance to one particular antibiotic. Your doctor also will prescribe or recommend an acid-suppressing drug, to help your stomach lining heal.

Drugs that can suppress acid include:

- Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs). These drugs stop acid from being produced in the stomach. Some examples of PPIs are omeprazole (Prilosec, others), esomeprazole (Nexium, others), lansoprazole (Prevacid, others) and pantoprazole (Protonix, others).

- Histamine (H-2) blockers. These medications block a substance called histamine, which triggers acid production. Examples include cimetidine (Tagamet) and ranitidine (Zantac).

- Bismuth subsalicylate. More commonly known as Pepto-Bismol, this drug works by coating the ulcer and protecting it from stomach acid.

Table 1. Recommended first-line therapies for H pylori infection

| Regimen | Drugs (doses) | Dosing frequency | Duration (days) | FDA approval |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clarithromycin triple | PPI (standard or double dose) | BID | 14 | Yesa |

| Clarithromycin (500 mg) | ||||

| Amoxicillin (1 grm) or Metronidazole (500 mg TID) | ||||

| Bismuth quadruple | PPI (standard dose) | BID | 10–14 | Nob |

| Bismuth subcitrate (120–300 mg) or subsalicylate (300 mg) | QID | |||

| Tetracycline (500 mg) | QID | |||

| Metronidazole (250–500 mg) | QID (250) | |||

| TID to QID (500) | ||||

| Concomitant | PPI (standard dose) | BID | 10–14 | No |

| Clarithromycin (500 mg) | ||||

| Amoxicillin (1 grm) | ||||

| Nitroimidazole (500 mg)c | ||||

| Sequential | PPI (standard dose)+Amoxicillin (1 grm) | BID | 5–7 | No |

| PPI, Clarithromycin (500 mg)+Nitroimidazole (500 mg)c | BID | 5–7 | ||

| Hybrid | PPI (standard dose)+Amox (1 grm) | BID | 7 | No |

| PPI, Amox, Clarithromycin (500 mg), Nitroimidazole (500 mg)c | BID | 7 | ||

| Levofloxacin triple | PPI (standard dose) | BID | 10–14 | No |

| Levofloxacin (500 mg) | QD | |||

| Amox (1 grm) | BID | |||

| Levofloxacin sequential | PPI (standard or double dose)+Amox (1 grm) | BID | 5–7 | No |

| PPI, Amox, Levofloxacin (500 mg QD), Nitroimidazole (500 mg)c | BID | 5–7 | ||

| LOAD | Levofloxacin (250 mg) | QD | 7–10 | No |

| PPI (double dose) | QD | |||

| Nitazoxanide (500 mg) | BID | |||

| Doxycycline (100 mg) | QD | |||

| BID, twice daily; FDA, Food and Drug Administration; PPI, proton pump inhibitor; TID, three times daily; QD, once daily; QID, four times daily. a Several PPI, clarithromycin, and amoxicillin combinations have achieved FDA approval. PPI, clarithromycin and metronidazole is not an FDA-approved treatment regimen. b PPI, bismuth, tetracycline, and metronidazole prescribed separately is not an FDA-approved treatment regimen. However, Pylera, a combination product containing bismuth subcitrate, tetracycline, and metronidazole combined with a PPI for 10 days is an FDA-approved treatment regimen. c Metronidazole or tinidazole. | ||||

Table 2. Recommended salvage therapies for H pylori infection (use if first line therapies failed)

| Regimen | Drugs (doses) | Dosing frequency | Duration (days) | FDA approval |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bismuth quadruple | PPI (standard dose) | BID | 14 | Noa |

| Bismuth subcitrate (120–300 mg) or subsalicylate (300 mg) | QID | |||

| Tetracycline (500 mg) | QID | |||

| Metronidazole (500 mg) | TID or QID | |||

| Levofloxacin triple | PPI (standard dose) | BID | 14 | No |

| Levofloxacin (500 mg) | QD | |||

| Amox (1 grm) | BID | |||

| Concomitant | PPI (standard dose) | BID | 10–14 | No |

| Clarithromycin (500 mg) | BID | |||

| Amoxicillin (1 grm) | BID | |||

| Nitroimidazole (500 mg) | BID or TID | |||

| Rifabutin triple | PPI (standard dose) | BID | 10 | No |

| Rifabutin (300 mg) | QD | |||

| Amox (1 grm) | BID | |||

| High-dose dual | PPI (standard to double dose) | TID or QID | 14 | No |

| Amox (1 grm TID or 750 mg QID) | TID or QID | |||

| BID, twice daily; FDA, Food and Drug Administration; PPI, proton pump inhibitor; TID, three times daily; QD, once daily; QID, four times daily. a PPI, bismuth, tetracycline, and metronidazole prescribed separately is not an FDA-approved treatment regimen. However, Pylera, a combination product containing bismuth subcitrate, tetracycline, and metronidazole combined with a PPI for 10 days is an FDA-approved treatment regimen. | ||||

American College of Gastroenterology – strong recommendation

Bismuth quadruple therapy consisting of a PPI, bismuth, tetracycline, and a nitroimidazole for 10–14 days is a recommended first-line treatment option. Bismuth quadruple therapy is particularly attractive in patients with any previous macrolide exposure or who are allergic to penicillin 30.

Concomitant therapy consisting of a PPI, clarithromycin, amoxicillin and a nitroimidazole for 10–14 days is a recommended first-line treatment option 30.

American College of Gastroenterology – Conditional recommendation

Clarithromycin triple therapy consisting of a PPI, clarithromycin, and amoxicillin or metronidazole for 14 days remains a recommended treatment in regions where H. pylori clarithromycin resistance is known to be <15% and in patients with no previous history of macrolide exposure for any reason 30.

Sequential therapy consisting of a PPI and amoxicillin for 5–7 days followed by a PPI, clarithromycin, and a nitroimidazole for 5–7 days is a suggested first-line treatment option 30.

Hybrid therapy consisting of a PPI and amoxicillin for 7 days followed by a PPI, amoxicillin, clarithromycin and a nitroimidazole for 7 days is a suggested first-line treatment option 30.

Levofloxacin triple therapy consisting of a PPI, levofloxacin, and amoxicillin for 10–14 days is a suggested first-line treatment option 30.

Fluoroquinolone sequential therapy consisting of a PPI and amoxicillin for 5–7 days followed by a PPI, fluoroquinolone, and nitroimidazole for 5–7 days is a suggested first-line treatment option 30.

Your doctor may recommend that you undergo testing for H. pylori at least four weeks after your treatment. If the tests show the treatment was unsuccessful, you may undergo another round of treatment with a different combination of antibiotic medications.

What factors predict successful eradication when treating H. pylori infection?

The main determinants of successful H. pylori eradication are the choice of regimen, the patient’s adherence to a multi-drug regimen with frequent side-effects, and the sensitivity of the H. pylori strain to the combination of antibiotics administered.

Resistance to clarithromycin, metronidazole and, increasingly, levofloxacin limits the success of the common eradication regimens in use today. The frequency of multi-drug resistance to these antibiotics appears to be increasing in prevalence. In general, H. pylori resistance to amoxicillin, tetracycline and rifabutin remains rare (under 5% for each currently).

The presence of clarithromycin resistance reduces the success of clarithromycin triple therapy by ~50% 31. Levofloxacin resistance lowers success rates of levofloxacin-containing regimens by ~20–40%, although data addressing the clinical impact of levofloxacin resistance are very limited 32. For metronidazole, where in vitro resistance to H. pylori is quite high worldwide, the effect on H. pylori eradication is less predictable. Metronidazole resistance reduces eradication rates by ~25% in triple therapies but less so in quadruple therapies and when PPIs are included in the regimen 31. Increasing the dose and duration of metronidazole also improves outcomes in metronidazole-resistant strains, demonstrating that, unlike clarithromycin and levofloxacin, in vitro metronidazole resistance is not an absolute predictor of eradication failure 33. Indeed, multiple mechanisms of metronidazole resistance in H. pylori have been described and the definition and measurement of metronidazole resistance among H. pylori strains remain to be adequately standardized.

- Helicobacter pylori infection and related gastrointestinal diseases. Makola D, Peura DA, Crowe SE. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2007 Jul; 41(6):548-58. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17577110/[↩]

- Helicobacter pylori gastritis and gastric MALT-lymphoma. Stolte M. Lancet. 1992 Mar 21; 339(8795):745-6.[↩]

- Consequences of Helicobacter pylori infection in children. Pacifico L, Anania C, Osborn JF, Ferraro F, Chiesa C. World J Gastroenterol. 2010 Nov 7; 16(41):5181-94. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2975089/[↩]

- Age of the association between Helicobacter pylori and man. Moodley Y, Linz B, Bond RP, Nieuwoudt M, Soodyall H, Schlebusch CM, Bernhöft S, Hale J, Suerbaum S, Mugisha L, van der Merwe SW, Achtman M. PLoS Pathog. 2012; 8(5):e1002693. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3349757/[↩]

- The Toronto Consensus for the Treatment of Helicobacter pylori Infection in Adults. Fallone CA, Chiba N, van Zanten SV, Fischbach L, Gisbert JP, Hunt RH, Jones NL, Render C, Leontiadis GI, Moayyedi P, Marshall JK. Gastroenterology. 2016 Jul; 151(1):51-69.e14.[↩]

- A five-year follow-up study on the pathological changes of gastric mucosa after H. pylori eradication. Zhou L, Sung JJ, Lin S, Jin Z, Ding S, Huang X, Xia Z, Guo H, Liu J, Chao W. Chin Med J (Engl). 2003 Jan; 116(1):11-4.[↩]

- The benefit of mass eradication of Helicobacter pylori infection: a community-based study of gastric cancer prevention. Lee YC, Chen TH, Chiu HM, Shun CT, Chiang H, Liu TY, Wu MS, Lin JT. Gut. 2013 May; 62(5):676-82.[↩]

- Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy to prevent gastric cancer in healthy asymptomatic infected individuals: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Ford AC, Forman D, Hunt RH, Yuan Y, Moayyedi P. BMJ. 2014 May 20; 348():g3174.[↩]

- Haley KP, Gaddy JA. Helicobacter pylori: Genomic Insight into the Host-Pathogen Interaction. International Journal of Genomics. 2015;2015:386905. doi:10.1155/2015/386905. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4334614/[↩]

- Gastroenteritis and Transmission of Helicobacter pylori Infection in Households. https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/12/11/06-0086_article[↩][↩]

- Perry S, Sanchez Md, Yang S, Haggerty TD, Hurst P, Perez-Perez G, et al. Gastroenteritis and Transmission of Helicobacter pylori Infection in Households. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12(11):1701-1708. https://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid1211.060086[↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Brown LM. Helicobacter pylori: epidemiology and routes of transmission. Epidemiol Rev. 2000;22:283–97[↩][↩]

- Malaty HM, El-Kasabany A, Graham DY, Miller CC, Reddy SG, Srinivasan SR, Age at acquisition of Helicobacter pylori infection: a follow-up study from infancy to adulthood. Lancet. 2002;359:931–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08025-X[↩]

- Parsonnet J. The incidence of Helicobacter pylori infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1995;9(Suppl 2):45–51[↩]

- Everhart JE, Kruszon-Moran D, Perez-Perez GI, Tralka TS, McQuillan G. Seroprevalence and ethnic differences in Helicobacter pylori infection among adults in the United States. J Infect Dis. 2000;181:1359–63[↩]

- Mendall MA, Goggin PM, Molineaux N, Levy J, Toosy T, Strachan D, Childhood living conditions and Helicobacter pylori seropositivity in adult life. Lancet. 1992;339:896–7[↩]

- Konno M, Fujii N, Yokota S, Sato K, Takahashi M, Sato K, Five-year follow-up study of mother-to-child transmission of Helicobacter pylori infection detected by a random amplified polymorphic DNA fingerprinting method. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:2246–50.[↩]

- Parsonnet J, Shmuely H, Haggerty T. Fecal and oral shedding of Helicobacter pylori from healthy infected adults. JAMA. 1999;282:2240–5[↩]

- Parsonnet J, Shmuely H, Haggerty T. Fecal and oral shedding of Helicobacter pylori from healthy infected adults. JAMA. 1999;282:2240–5.[↩][↩]

- Luzza F, Mancuso M, Imeneo M, Contaldo A, Giancotti L, Pensabene L, Evidence favouring the gastro-oral route in the transmission of Helicobacter pylori infection in children. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;12:623–7.[↩]

- Haggerty T, Shmuely H, Parsonnet J. Helicobacter pylori in cathartic stools of subjects with and without cimetidine-induced hypochlorhydria. J Med Microbiol. 2003;52:189–91.[↩]

- hmuely H, Samra Z, Ashkenazi S, Dinari G, Chodick G, Yahav J. Association of Helicobacter pylori infection with Shigella gastroenteritis in young children. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:2041–5.[↩]

- Graham DY, Opekun AR, Osato MS, El-Zimaity HM, Lee CK, Yamaoka Y, Challenge model for Helicobacter pylori infection in human volunteers. Gut. 2004;53:1235–43.[↩]

- Nurgalieva ZZ, Conner ME, Opekun AR, Zheng CQ, Elliott SN, Ernst PB, B-cell and T-cell immune responses to experimental Helicobacter pylori infection in humans. Infect Immun. 2005;73:2999–3006[↩]

- Malaty HM, El-Kasabany A, Graham DY, Miller CC, Reddy SG, Srinivasan SR, Age at acquisition of Helicobacter pylori infection: a follow-up study from infancy to adulthood. Lancet. 2002;359:931–5.[↩]

- Vaira D, Vakil N. Blood, urine, stool, breath, money, and Helicobacter pylori. Gut. 2001;48:287–9.[↩]

- Goodman KJ, O’Rourke K, Day RS, Wang C, Nurgalieva Z, Phillips CV, Dynamics of Helicobacter pylori infection in a US-Mexico cohort during the first two years of life. Int J Epidemiol. 2005;34:1348–55.[↩]

- Thomas JE, Dale A, Harding M, Coward WA, Cole TJ, Weaver LT. Helicobacter pylori colonization in early life. Pediatr Res. 1999;45:218–23.[↩]

- Kumagai T, Malaty HM, Graham DY, Hosogaya S, Misawa K, Furihata K, Acquisition versus loss of Helicobacter pylori infection in Japan: results from an 8-year birth cohort study. J Infect Dis. 1998;178:717–21.[↩]

- Treatment of Helicobacter pylori Infection. Am J Gastroenterol 2017; 112: 212–238; doi:10.1038/ajg.2016.563. http://gi.org/guideline/treatment-of-helicobacter-pylori-infection/[↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Fischbach L, Evans EL. Meta-analysis: the effect of antibiotic resistance status on the efficacy of triple and quadruple first-line therapies for Helicobacter pylori. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2007;26:343–357.[↩][↩]

- Kuo CH, Hu HM, Kuo FC et al. Efficacy of levofloxacin-based rescue therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection after standard triple therapy: a randomized controlled trial. J Antimicrob Chemother 2009;63:1017–1024.[↩]

- Smith SM, O’Morain C, McNamara D. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing for Helicobacter pylori in times of increasing antibiotic resistance. World J Gastroenterol 2014;20:9912–9921.[↩]