Hepatic encephalopathy

Hepatic Encephalopathy also referred to as portosystemic encephalopathy, is a serious but treatable complex neuropsychiatric syndrome (if caught early and treated promptly) that causes temporary worsening of brain function in people with advanced liver disease or chronic liver failure, which in most cases in Western societies is caused by chronic alcohol abuse. There are approximately 7-11 million cases of hepatic encephalopathy prevalent in the United States, with approximately 150,000 patients newly diagnosed each year 1. Of the newly diagnosed patients, approximately 20% present with cirrhosis, and almost 60% of cases occur in the presence of chronic hepatitis C either alone or in combination with alcohol-related liver disease 2.

When your liver is damaged it can no longer remove toxic substances from your blood. These toxins build up and can travel through your body until they reach your brain, causing mental and physical symptoms of hepatic encephalopathy. These substances may be made by your body (ammonia), or substances that you take in (medicines). Hepatic encephalopathy may occur suddenly or it may develop slowly over time.

In some cases, hepatic encephalopathy is a short-term problem that can be corrected. It may also occur as part of a long-term (chronic) problem from liver disease that gets worse over time.

Hepatic encephalopathy occurs as a complication of advanced liver disease (e.g. 30-45% of patients with cirrhosis, 10-50% of patients with transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) procedure), which may be acute or chronic 1.

There is no specific test used to diagnose hepatic encephalopathy. Patients frequently are misdiagnosed, particularly in the early stages of hepatic encephalopathy, when symptoms occur that are common to a number of psychiatric disorders, such as euphoria, anxiety, depression, and sleep disorders. Once your doctor has determined you have hepatic encephalopathy, the first step is to identify and treat any factors that caused it.

Depending on the cause, treatment may include:

- Medicine to treat infections

- Procedures to stop active bleeding

- Therapy for kidney problems

- Stopping the use of certain medications that depress central nervous system function and can trigger hepatic encephalopathy

Triggers of hepatic encephalopathy include renal failure, gastrointestinal bleeding (e.g. esophageal varices), constipation, infection, medication non-compliance, excessive dietary protein intake, dehydration (e.g. fluid restriction, diuretics, diarrhea, vomiting, excessive paracentesis), electrolyte imbalance, consumption of alcohol, or consumption of certain sedatives, analgesics or diuretics all in the setting of chronic liver disease. In some cases, hepatic encephalopathy may occur following the creation of a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) procedure 3. In the case of chronic liver disease, as it tends to have an insidious onset, most patients do not seek treatment until late in the course of the disease – once complications develop.

Once any triggering factors have been addressed, treatment is aimed at lowering the level of ammonia and other toxins in your blood. Since these toxins originally arise in your gastrointestinal (GI) system, therapies are aimed at your gut to eliminate or reduce the production of toxins. The two types of medications used to do this are lactulose, a man-made sugar, and antibiotics.

It’s important to continue your treatment for as long as necessary to keep hepatic encephalopathy from coming back.

Once symptoms become severe, hepatic encephalopathy can quickly worsen and become a medical emergency resulting in prolonged hospitalization. But with continuous treatment, hepatic encephalopathy can usually be controlled. So it’s important to tell your doctor about any warnings signs you have as soon as you, or a family member or friend, notice them.

The best way to reduce the risk of hepatic encephalopathy recurrence is to manage your liver disease and stay on maintenance therapy with lactulose and/or rifaximin, as directed by your doctor.

Why is your liver important?

You only have one liver and it’s one of the largest and most important organs in your body. Your liver performs many jobs to keep you healthy including filtering everything that enters your body, such as food, drink and medicine.

After your intestines break down things that you eat or drink into their component parts, your liver is responsible for separating the good stuff from the bad. It sends the good things – such as vitamins and nutrients – into your bloodstream for your body to use and changes the bad or toxic things, making them harmless.

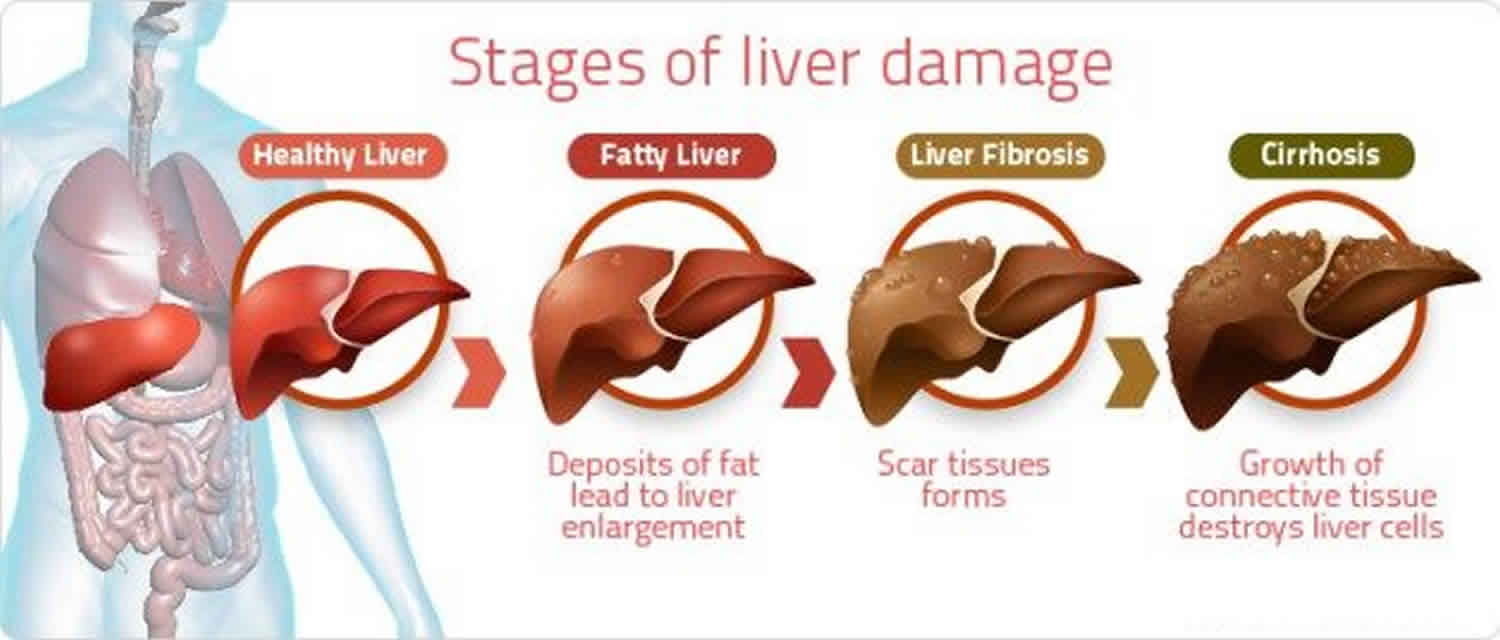

Hepatic encephalopathy is most often seen in people with chronic liver disease. Anything that damages your liver over many years – such as long-term alcohol abuse or chronic hepatitis – can cause it to form scar tissue (cirrhosis). As hard scar tissue replaces soft, healthy tissue two things begin to happen:

- The scarred tissue cannot carry out the process of changing toxins into harmless substances like a healthy liver normally would.

- The scarred tissue can block the flow of blood through the liver causing high blood pressure in the veins in and around your liver (called the portal venous system). This condition is known as portal hypertension.

When your liver can’t filter toxins from your blood or when blood flow through your liver is blocked, toxins build up in your bloodstream and can get into your brain.

Ammonia, which is produced by your body when proteins are digested, is one of the toxins that’s normally made harmless by your liver. But when ammonia, or a range of other toxic substances, build up in your body when your liver isn’t working well, it may affect your brain and cause hepatic encephalopathy.

What is liver cirrhosis?

Cirrhosis is the permanent scarring of the liver. The hard scar tissue replaces the soft healthy tissue. The liver will fail and will not work properly if cirrhosis is not treated.

The symptoms of cirrhosis may vary over time causing complications. Loss of appetite, tiredness, nausea, weight loss, abdominal pain, spider-like blood vessels or severe itching may be symptoms to look out for.

For some people, cirrhosis is diagnosed unintentionally. Cirrhosis often does not have any specific signs and symptoms in the early stage. The non-specific symptoms may be:

- Nausea

- Loss of appetite

- Fatigue

- Diarrhea

- Jaundice (yellowing of the skin and whites of the eyes)

As cirrhosis progresses, symptoms and complications can appear that make it apparent that the liver is not doing well. These could be the symptoms of hepatic encephalopathy and other complications due to cirrhosis. In addition to hepatic encephalopathy, following complications are signs of liver damage or cirrhosis:

- Fluid build up and painful swelling of the legs (edema) and abdomen (ascites)

- Bruising and bleeding easily

- Enlarged veins in the lower esophagus (esophageal varices) and stomach (gastropathy)

- Enlarged spleen (splenomegaly)

- Stone-like particles in gallbladder and bile duct (gallstones)

- Liver cancer (hepatocellular carcinoma)

Complications of cirrhosis may appear as jaundice (a yellow discoloration of the skin and whites of the eyes), gallstones, bruising and bleeding easily, fluid build-up and painful swelling of the legs (edema) and abdomen (ascites) or hepatic encephalopathy.

Chronic liver failure indicates that the liver has been failing gradually, possibly for years.

If the liver is failing, a liver transplant may be needed in some cases.

Who is at risk of hepatic encephalopathy?

Here are some facts about who gets hepatic encephalopathy:

- Most often seen in people with cirrhosis

- Can occur in people of any age who have acute or chronic liver disease

- Affects men and women equally

- More likely to occur in people that have had a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) procedure or surgical shunts

About 7 out of 10 people with cirrhosis develop minimal hepatic encephalopathy (Grade 0); the exact number isn’t known because symptoms are subtle at this stage, making it difficult to diagnose. What is known is that you are at least three times more likely to progress from minimal to obvious, or overt, symptoms of hepatic encephalopathy if it’s not diagnosed early. So communicate with your doctor right away if you suspect you may have hepatic encephalopathy so that treatment can be started as soon as possible.

People with chronic liver disease are at greater risk of developing a more chronic form of the disorder where symptoms get worse or continue to come back, known as “hepatic encephalopathy recurrence.” It isn’t known why some people experience hepatic encephalopathy recurrences and others do not, but there are several possible triggers.

Hepatic encephalopathy stages

The severity of hepatic encephalopathy is judged according to your symptoms. The most commonly used staging scale of hepatic encephalopathy is called the West Haven Grading System (a semi-quantitative grading of mental state – based on the level of dependence on therapy and the impairment in autonomy, behaviour, consciousness, intellectual function) 4:

- Grade 0: Minimal hepatic encephalopathy

- This stage is very hard to detect as changes in your memory, concentration and intellectual functioning are so minimal that they may not be outwardly noticeable, even to you. Coordination can be affected and although subtle, may impact your ability to drive a car. If you recently had poorer performance at work or have committed a number of traffic violations while driving, it would be worth bringing this to the attention of your healthcare provider. You may be referred for special testing, called neuropsychiatric testing, to evaluate your thinking abilities by doing a number of specifically designed tasks with a trained examiner. If your test reveals some deficits, your healthcare provider will likely schedule frequent follow-up visits to closely follow your condition. There are currently no medications approved by the FDA to treat minimal hepatic encephalopathy.

- Grade 1: Mild hepatic encephalopathy

- You may have a short attention span, notice mood changes like depression or irritability, and have sleep problems.

- Grade 2: Moderate hepatic encephalopathy

- You may keep forgetting things, have no energy and exhibit inappropriate behavior. Your speech may be slurred and you can have trouble doing mental tasks such as basic math. Your hands might shake and you can have difficulty writing.

- Grade 3: Severe hepatic encephalopathy

- You may be confused as to where you are or what day it is and be extremely sleepy, but can still be woken up. You may be unable to do basic mental tasks, feel extremely anxious and act strangely.

- Grade 4: Coma

- The last stage of hepatic encephalopathy is when the person becomes unconscious and slips into a coma.

World Health Congress of Gastroenterology Criteria

- Type A (acute)

- hepatic encephalopathy associated with acute liver failure, typically with cerebral edema

- Type B (bypass)

- hepatic encephalopathy caused by portal-systemic shunting (without associated intrinsic liver disease)

- Type C (cirrhosis)

- hepatic encephalopathy in patients with cirrhosis – subdivided into episodic, persistent and minimal encephalopathy

Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy

Minimal hepatic encephalopathy is a form of hepatic encephalopathy that is not associated with any grossly evident signs of cognitive dysfunction, but with cognitive deficits that can be demonstrated with neuropsychological testing. Minimal hepatic encephalopathy has been shown to impair overall quality of life and ability to work and has been associated with a higher risk of motor vehicle accidents. Patients with minimal hepatic encephalopathy are also more prone to falls and have an increased risk of their condition progressing to overt hepatic encephalopathy. Psychometric testing remains the standard for diagnosis of minimal hepatic encephalopathy – these include the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status and PSE-Syndrome-Test – which incorporate a number of neuropsychological tests aimed at measuring multiple domains of cognitive function (which tend to be more reliable than older tests focused on assessing single domains of cognitive function). Treatment with Rifaximin or lactulose has also been shown to improve the quality of life in patients with minimal hepatic encephalopathy, and Rifaximin has furthermore been shown to improve driving performance in simulated experiments. The combination of both Rifaximin and lactulose has been shown to prevent the recurrence of episodic hepatic encephalopathy over a period of 6 months follow-up 5.

Causes of hepatic encephalopathy

An important function of your liver is to make toxic substances in your body harmless. Hepatic encephalopathy can occur suddenly and you may become ill very quickly. Liver failure occurs if your liver has lost all of its function due to cirrhosis caused by different liver diseases. Hepatic encephalopathy is most often seen in people with chronic liver disease and is a major complication of cirrhosis.

Causes of hepatic encephalopathy may include:

- Hepatitis A or B infection (uncommon to occur this way)

- Blockage of blood supply to the liver

- Poisoning by different toxins or medicines

- Constipation

- Upper gastrointestinal bleeding

People with severe liver damage often suffer from hepatic encephalopathy. The end result of chronic liver damage is cirrhosis. Common causes of chronic liver disease are:

- Severe hepatitis B or C infection

- Alcohol abuse

- Autoimmune hepatitis

- Bile duct disorders such as primary biliary cirrhosis and primary sclerosing cholangitis

- Some medicines

- Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH)

- Metabolic diseases such as hemochromatosis, Wilson disease and alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency

Once you have liver damage, episodes of worsening brain function may be triggered by:

- Less body fluids (dehydration)

- Eating too much protein

- Low potassium or sodium levels

- Bleeding from the intestines, stomach, or food pipe (esophagus)

- Infections

- Kidney problems

- Low oxygen levels in the body

- Shunt placement or complications

- Surgery

- Narcotic pain or sedative medicines

Disorders that can appear similar to hepatic encephalopathy may include:

- Alcohol intoxication

- Alcohol withdrawal

- Bleeding under the skull

- Brain disorder caused by lack of vitamin B1

Hepatic encephalopathy triggers

An episode of hepatic encephalopathy may be triggered by any of the following things:

- Infections

- Constipation

- Dehydration: This happens when you don’t get enough water or other fluids.

- Bleeding from your intestines, stomach or esophagus (the tube that connects your mouth to your stomach). This is referred to as gastrointestinal, or GI, bleeding.

- Medications that affect your nervous system, such as sleeping pills, antidepressants or tranquilizers.

- Kidney problems

- An alcohol binge

- Surgery

- Having a portosystemic shunt: This is a tube that’s placed in your liver, sometimes called a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) procedure or a surgical procedure to reroute blood flow and relieve high blood pressure in the veins in and around your liver, a condition called portal hypertension.

Hepatic encephalopathy pathophysiology

Putative neurotoxins include ammonia, short-chain fatty acids, mercaptans, false neurotransmitters (e.g. tyramine, octopamine, beta-phenylethanolamines), manganese, and GABA – though ammonia is the most widely recognized 6.

Under normal conditions, ammonia is produced by bacteria in the gastrointestinal tract (e.g. breakdown product of amines, amino acids, purines, and urea) followed by metabolism and clearance by the liver. In the case of cirrhosis or advanced liver dysfunction, however, there is either a decrease in the number of functioning hepatocytes, portosystemic shunting, or both, resulting in decreased ammonia clearance and hyperammonemia.

Once ammonia crosses the blood brain barrier, it has multiple neurotoxic effects. These include alterations in molecular transport (e.g. amino acids, electrolytes, water) in astrocytes and neurons, increased synthesis of glutamine from glutamate by astrocytes, inhibition of excitatory and inhibitory postsynaptic potential generation, impaired amino acid metabolism, and impaired energy utilization as a result of increased GABA activity.

Hepatic encephalopathy signs and symptoms

Hepatic encephalopathy encompasses a range of mental and physical symptoms depending on the severity of the condition. Symptoms of hepatic encephalopathy are graded on a scale of grades 1 to 4. Symptoms may begin slowly and gradually get worse, or they may occur suddenly and be severe from the start.

Early hepatic encephalopathy symptoms may be mild and include:

- Breath with a musty or sweet odor

- Changes in sleep patterns

- Changes in thinking

- Mild confusion

- Forgetfulness

- Personality or mood changes

- Poor concentration and judgment

- Worsening of handwriting or loss of other small hand movements

Mild to moderate symptoms of hepatic encephalopathy may include the following mental and physical changes:

- Mental

- Mild confusion

- Short attention span

- Forgetfulness

- Mood swings

- Personality changes

- Inappropriate behavior

- Difficulty doing basic math

- Physical

- Change in sleep patterns (like sleeping during the day and staying up at night)

- Difficulty writing or doing other small hand movements

- Breath that smells musty or sweet

- Slurred speech

Severe hepatic encephalopathy symptoms may include:

- Abnormal movements or shaking of hands or arms called “flapping tremor” or asterixis

- Agitation, excitement, or seizures (occur rarely)

- Disorientation

- Drowsiness or confusion

- Behavior or personality changes

- Jumbled, slurred speech that can’t be understood

- Slowed or sluggish movement

- Extreme sleepiness

People are often not able to care for themselves because of these symptoms.

In the most severe form of hepatic encephalopathy, people can become unresponsive, unconscious and enter a coma.

Signs of hepatic encephalopathy may include:

- Shaking of the hands (“flapping tremor”) when trying to hold arms in front of the body and lift the hands

- Problems with thinking and doing mental tasks

- Marked confusion

- Severe anxiety or fearfulness

- Disorientation regarding time and place

- Inability to perform mental tasks such as doing basic math

- Signs of liver disease, such as yellow skin and eyes (jaundice) and fluid collection in the abdomen (ascites)

- Musty odor to the breath and urine

Hepatic encephalopathy diagnosis

Hepatic encephalopathy is difficult to diagnose in alcoholic patients because no single clinical or laboratory test is sufficient to establish the diagnosis. Patients frequently are misdiagnosed, particularly in the early stages of hepatic encephalopathy, when symptoms occur that are common to a number of psychiatric disorders, such as euphoria, anxiety, depression, and sleep disorders.

A hepatic encephalopathy diagnosis is based on a combination of three things:

- Your medical history;

- Your symptoms;

- A thorough clinical exam by your healthcare provider.

The following characteristics have been proposed as helpful in diagnosing hepatic encephalopathy in alcoholic cirrhotic patients 7:

- History of liver disease.

- A slowing (i.e., reduced frequency) of brain waves measured by electroencephalography (EEG).

- Impaired performance on neuropsychological tests assessing visuospatial and perceptual–motor control (e.g., line–drawing tests and number connection tests).

- Asterixis (“flapping tremor”).

- Foul–smelling breath associated with liver disease (i.e., fetor hepaticus).

- Enhanced rate of breathing (i.e., hyperventilation).

- Elevated concentrations of ammonia in the serum2 after a period of fasting. (2 The serum is the clear portion of the blood that remains after blood cells, platelets, and blood–clotting molecules have been removed.)

- Reduced awareness or consciousness.

Although these signs and symptoms are useful tools for diagnosing hepatic encephalopathy, they also occur in brain disorders caused by metabolic disturbances and therefore are not specific to hepatic encephalopathy. Furthermore, whether and to what extent a patient displays each symptom may vary depending on fluctuations in the patient’s medical and drug status or diet. For example, sedatives or meals high in protein frequently trigger episodes of hepatic encephalopathy in alcoholic patients with cirrhosis. Thus, an asymptomatic cirrhotic patient frequently begins to show signs of hepatic encephalopathy following ingestion of large amounts of protein, which is a source of ammonia. Also, small doses of sedatives may trigger overt encephalopathy in these patients.

Tests done may include:

- Complete blood count or hematocrit to check for anemia

- CT scan of the head or MRI

- Electroencephalogram (EEG)

- Liver function tests

- Prothrombin time

- Serum ammonia level

- Sodium level in the blood

- Potassium level in the blood

- BUN (blood urea nitrogen) and creatinine to see how the kidneys are working

Blood tests can identify abnormalities associated with liver and kidney dysfunction, infections, bleeding and other conditions that may contribute to hepatic encephalopathy. However, these tests are not specific to hepatic encephalopathy and simply aid in making the Hepatic Encephalopathy diagnosis which is based on your history and symptoms. Ammonia levels are sometimes used, but these values alone cannot diagnose hepatic encephalopathy.

Because many of the symptoms of hepatic encephalopathy also occur in people with other types of brain disease or damage – such as stroke, brain tumor, or bleeding inside the skull – your healthcare provider may order specialized pictures of your brain to rule these out.

These imaging tests, as they’re called, are obtained by using various types of equipment and will likely include MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) and CT (computerized tomography) scans. In addition, your doctor may order an EEG (electroencephalogram), a test that measures the electrical activity of your brain, to look for brain wave changes associated with hepatic encephalopathy.

Since there is no specific “hepatic encephalopathy test” the diagnosis of hepatic encephalopathy is often referred to as a diagnosis of exclusion. This means that it’s important for your doctor to exclude – or rule out – other possible causes for your symptoms in order to correctly diagnose you with hepatic encephalopathy.

Hepatic encephalopathy treatment

Treatment of hepatic encephalopathy depends upon the cause. Because hepatic encephalopathy is a complicated condition, a multidisciplinary approach is often required to manage it.

If you’ve been given a diagnosis of hepatic encephalopathy, it’s likely you’ve had liver disease for many years that progressed to cirrhosis, which means you’ve probably been under the care of a liver specialist. Liver specialists can include the following healthcare providers:

- Hepatologists: Physicians who specialize in the treatment of people with liver diseases.

- Gastroenterologists: Physicians who specialize in the treatment of people with disorders of the digestive organs, including the liver.

- Nurse practitioners whose practice concentrates on people with liver disease. Nurse practitioners are registered nurses who are prepared – through advanced education and clinical training – to assume some of the duties formerly assumed only by physicians. They can provide a wide range of healthcare services, including the diagnosis and management of common, as well as complex medical conditions.

- Physicians assistants whose practice concentrates on people with liver disease. Physicians assistants practice medicine under the supervision of a physician. They take medical histories, provide diagnostic screenings, order and interpret tests, prescribe medication and perform medical procedures.

Additionally, you may be followed by a primary care physician. These are internists or family physicians that provide preventative care and disease management, often in consultation with your liver specialist.

At times, you may be referred to other members of the healthcare team such as a:

- Nutritionist or dietician for information about food intake and meal planning

- Mental health therapist to help you deal with emotional issues such as depression and anxiety

- Social worker or case manager to assist you in accessing health and social services such as Medicaid, disability and financial assistance

Hepatic encephalopathy treatment options

The therapies used for hepatic encephalopathy treatment vary depending upon a number of factors including:

- The precipitating cause, or triggering event

- Your specific symptoms

- The severity of the disorder

- The severity of your underlying liver disease

- Your age and general health

The first step is to identify and treat precipitating factors such as infection, gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding, certain drugs or kidney dysfunction. Hepatic encephalopathy treatment therapies may include medications to treat infections, medications or procedures to control bleeding, stopping the use of medications that can trigger an episode and any appropriate therapy for kidney issues.

If hepatic encephalopathy presents as a medical emergency requiring immediate hospitalization, life support may be necessary to help with breathing or blood circulation, particularly if there’s a loss of consciousness. Patients at risk for aspiration or respiratory compromise should be prophylactically intubated and monitored in the ICU. In the case of patients with concomitant alcohol withdrawal, medications that depress the central nervous system (e.g. benzodiazepines) should be avoided 8.

Once the precipitating factors have been addressed, treatment is aimed at lowering the level of ammonia and other toxins in your blood. Since these toxins originally arise in your gastrointestinal system, therapies are aimed at your gut to eliminate or reduce the production of toxins. The two medicines used most often to treat hepatic encephalopathy are lactulose, a synthetic or man-made sugar, and certain antibiotics. Sometimes lactulose and antibiotics are used together.

Medications

If changes in brain function are severe, a hospital stay may be needed. In the hospital:

- Bleeding in the digestive tract must be stopped.

- Infections, kidney failure, and changes in sodium and potassium levels need to be treated.

Lactulose

- Lactulose/lactitol (a non-absorbable osmotic laxative that also helps convert ammonia to non-absorbable ammonium in the gastrointestinal tract) works by drawing water from your body into your colon, which softens stools and causes you to have more bowel movements. This helps to lessen the absorption of toxins in your intestines by flushing toxins out of your system.

- Reduces the amount of ammonia in your blood by drawing the ammonia into the colon where it is removed from the body.

- Helps during hepatic encephalopathy recurrences and also makes them less likely to occur.

Antibiotics

- Antibiotics (e.g. rifaximin, neomycin/paromomycin/metronidazole, or vancomycin) are often given empirically due to the frequency of infection as an underlying cause.

- Antibiotics work by stopping the growth of certain bacteria that create toxins from your digested food. By reducing these bacteria, antibiotics reduce the amount of toxins produced in your body.

- Help to prevent hepatic encephalopathy recurrences and reduce the chance of being hospitalized due to hepatic encephalopathy.

- A few different antibiotics are used to treat hepatic encephalopathy. Your healthcare provider will choose the one that’s best for you.

LOLA (L-ornithine and L-aspartate preparation)

- LOLA (L-ornithine and L-aspartate preparation) increases the use of ammonia in the urea cycle to produce urea.

Zinc

- Zinc is used to correct underlying deficiency common in cirrhotic patients) either alone or in combination with each other and/or antibiotics.

Medication compliance

In order to get maximum benefit from your medications, it’s important to take them as prescribed – meaning taking the right dose, the right way, at the right time, for as long as necessary. With proper adherence to therapy, the progression of hepatic encephalopathy can be slowed and sometimes even stopped.

Adhering to other aspects of your treatment plan is also important. Communicating with members of your healthcare team, keeping your medical appointments, getting the necessary lab tests, and eating an appropriate diet will help to maximize your chance of treatment success and minimize potential problems.

Rehabilitation care

Patients with hepatic encephalopathy are at risk for recurrent episodes of encephalopathy.

Protein restriction is only of use in patients with acute flare ups and is not justified in chronic cases. These patients need nutrition as they have a high catabolic rate and severe wasting.

Vegetable protein is better tolerated compared to animal protein.

Medications should be used with caution; one should avoid constipation, blood thinners and use prophylaxis against spontaneous bacterial peritonitis.

Liver transplant

When the liver can no longer perform its vital functions a liver transplant may be the only option. A liver transplant is the process of replacing a damaged liver with a donated, healthy liver from someone else. Most of the time, a liver is donated from someone who has died. In rare cases, a living person donates a portion of their liver. Liver transplants require that the blood type and body size of the donor match the person receiving the liver transplant. Donated livers come from living and non-living donors. Liver transplant surgery usually takes between four and twelve hours. Most patients stay in the hospital for up to three weeks after surgery. There are currently over 17,000 patients waiting for a liver transplant here in the United States. Historically between 5,000 to 6,000 liver transplants happen annually. In the U.S., there are more people who need a liver transplant than there are donated livers. The major reason for liver transplants here in the U.S. is hepatitis C.

There are many things that are taken into consideration when getting evaluated for a liver transplant. You need to be healthy enough to tolerate the surgery and recovery period – which is long – and have a support system in place that can help you through the process. Your doctor will determine if your liver disease is severe enough that referral for a transplant is appropriate.

The process to be eligible for a liver transplant is:

- Person’s doctor refers him or her to be seen at a transplant center;

- At the transplant center, the transplant team evaluates the person’s overall physical and mental health, plan to pay for transplant related medical expenses, and emotional support family and friends will provide;

- Based on the findings, the team decides if the person is eligible for a liver transplant;

- If the person is eligible, the center will add him or her to the transplant waiting list.

The waiting list is prioritized so the sickest people are at the top of the list. The time a person spends on the waiting list depends on:

- Blood type

- Body size

- Stage of liver disease

- Overall health

- Availability of a matching liver

Most patients return to a regular lifestyle six months to a year after a successful liver transplant. In some patients, the liver disease they had before the transplant comes back and they may need treatment or another transplant.

Hepatic encephalopathy prognosis

With or without treatment, the prognosis for most patients with hepatic encephalopathy is poor. The development of hepatic encephalopathy negatively impacts patient survival. None of the current treatments are curative, and liver transplant is not readily available for most patients. The occurrence of encephalopathy severe enough to lead to hospitalization is associated with a survival probability of 42% at 1 year of follow-up and 23% at 3 years 9.

Approximately 30% of patients dying of end-stage liver disease experience significant encephalopathy, approaching coma 10.

- Mandiga P, Foris LA, Kassim G, et al. Hepatic Encephalopathy. [Updated 2019 Jun 14]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2019 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430869[↩][↩]

- Acharya C, Bajaj JS. Current Management of Hepatic Encephalopathy. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2018 Nov;113(11):1600-1612.[↩]

- Fiati Kenston SS, Song X, Li Z, Zhao J. Mechanistic insight, diagnosis, and treatment of ammonia-induced hepatic encephalopathy. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019 Jan;34(1):31-39.[↩]

- Taş A, Yalçın MS, Sarıtaş B, Kara B. Comparison of prognostic systems in cirrhotic patients with hepatic encephalopathy. Turk J Med Sci. 2018 Jun 14;48(3):543-547.[↩]

- Tapper EB, Parikh ND, Waljee AK, Volk M, Carlozzi NE, Lok AS. Diagnosis of Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy: A Systematic Review of Point-of-Care Diagnostic Tests. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2018 Apr;113(4):529-538.[↩]

- Levitt DG, Levitt MD. A model of blood-ammonia homeostasis based on a quantitative analysis of nitrogen metabolism in the multiple organs involved in the production, catabolism, and excretion of ammonia in humans. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2018;11:193-215.[↩]

- Tarter, R.E.; Arria, A.; and Van Thiel, D.H. Liver–brain interactions in alcoholism. In: Hunt, W.A., and Nixon, S.J., eds. Alcohol–Induced Brain Damage. NIAAA Research Monograph No. 22. Rockville, MD: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 1993. pp 415–429.[↩]

- Oey RC, de Wit K, Moelker A, Atalik T, van Delden OM, Maleux G, Erler NS, Takkenberg RB, de Man RA, Nevens F, van Buuren HR. Variable efficacy of TIPSS in the management of ectopic variceal bleeding: a multicentre retrospective study. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2018 Nov;48(9):975-983.[↩]

- Bustamante J, Rimola A, Ventura PJ, et al. Prognostic significance of hepatic encephalopathy in patients with cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 1999 May. 30(5):890-5.[↩]

- Ferenci P. Hepatic encephalopathy. Haubrich WS, Schaffner F, Berk JE, eds. Bockus Gastroenterology. 5th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: WB Saunders; 1995. 1998-2003.[↩]