Hereditary angioedema

Hereditary angioedema also known as HAE, hereditary angioneurotic edema or C1-esterase inhibitor deficiency (C1-INH-HAE), is a very rare and potentially life-threatening genetic disorder that is associated with recurrent attacks (also called episodes) of noninflammatory, nonpitting, self-limiting edema (swelling) affecting subcutaneous tissues and gastrointestinal and oropharyngeal mucosa without urticaria 1, 2. The frequency of attacks usually increases after puberty 3. Attacks most often affect 3 parts of the body: skin – the most common sites are the face (such as the lips and eyes), hands, arms, legs, genitals, and buttocks. Skin swelling can cause pain, dysfunction, and disfigurement, although it is generally not dangerous and is temporary. Gastrointestinal tract – the stomach, intestines, bladder, and/or urethra may be involved. This may cause symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal pain; abdominal angioedema attacks can lead to unnecessary surgery and delay in diagnosis, as well as to narcotic dependence due to severe pain; and cutaneous attacks can be disfiguring and disabling 4. Upper airway (such as the larynx and tongue) – this can cause upper airway obstruction and asphyxiation. The majority of attacks affecting the airway resolve before complete airway obstruction. Attacks may involve one area of the body at a time, or they may involve a combination of areas. They always go away on their own but last from 2 to 4 days. Attacks generally continue throughout life, but the frequency of attacks can be significantly reduced with therapy. While people with hereditary angioedema have reported various triggers of attacks, emotional stress, physical stress, and dental procedures are the most commonly reported triggers.

The typical signs and symptoms of hereditary angioedema start during childhood or adolescence, worsen during puberty, and persist throughout the patient’s lifetime 5. A retrospective analysis of 209 patients with hereditary angioedema by Bork et al 6 reported a mean age at disease onset of 11.2 years (range 1 to 40 years), with approximately 50% of patients having their first attack before age 10. After the onset of clinical symptoms, most patients with hereditary angioedema have recurrent attacks of edema with symptom-free intervals of less than 12 months, although considerable variability exists in attack frequency—untreated patients may have attacks every 7 to 14 days on average 7, while patients whose disease is well controlled with long-term prophylactic therapy may be symptom-free for a decade or more 6. The severity of attacks also varies considerably, even within affected families and even if they have the same genetic mutation 6.

Usual attacks start with a prodromal symptoms such as a transient reticular rash (erythema marginatum), skin tingling or vague complaints such as nausea, anxiety, fatigue, or flu-like symptoms 8. One-third of patients with hereditary angioedema experience early symptoms of erythema marginatum (Figure 6) that may be confused for urticaria (Figure 5). Erythema marginatum is a non-pruritic form of annular erythema more commonly associated with rheumatic fever. The lesions can be static or extend peripherally in a centrifugal way. This is followed by slowly progressive swelling that gradually subsides over 48 to 72 hours. The type of swelling seen in hereditary angioedema is not associated with the presence of urticaria and it is not responsive to the use of steroids and/or antihistamines. Oropharyngeal swelling is of great concern as it can lead to asphyxia and death if it not recognized or treated appropriately. These type of attacks are less frequent, but more than half of hereditary angioedema patients have at least 1 oropharyngeal attack during their life. Abdominal attacks carry significant morbidity and often require emergency visits, hospitalizations, and unnecessary procedures.

Hereditary angioedema attacks are accompanied by neither inflammatory nor allergic components, and therefore generally do not respond to treatment with antihistamines, epinephrine, or corticosteroids—this clinical feature often provides an important diagnostic clue 9.

Hereditary angioedema has an incidence of approximately 1 in 50,000 individuals 5. Hereditary angioedema shows no ethnic- or sex-based differences but tends to be more severe in women 7. Hereditary angioedema leads to about 15,000 to 30,000 emergency department visits per year 10.

Hereditary angioedema may be caused by the lack of or a dysfunctional C1 inhibitor (C1-INH) protein due to genetic changes (300 pathogenic variants) in the C1 inhibitor (C1-INH) gene (also called the SERPING1 gene) or in the F12 gene 11. In some cases, the cause is not yet known. These types are also characterized by abnormal complement protein levels. Most cases of hereditary angioedema are inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion, with approximately 25% of cases arising from de novo mutations (spontaneous mutation of the particular gene at conception). However, not all people with a SERPING1 genetic change will develop symptoms of hereditary angioedema. For this reason, the nomenclature has been developed to replace the initial use of type 1, 2, or 3 HAE. Instead, the names are hereditary angioedema with deficient C1-inhibitor (type 1 hereditary angioedema), hereditary angioedema with dysfunctional C1-inhibitor (type 2 hereditary angioedema), and hereditary angioedema with normal C1-inhibitor (type 3 hereditary angioedema). Though unique in the testing that leads to the diagnosis, they all behave similarly with angioedema 12.

3 types of hereditary angioedema 13:

- Hereditary angioedema with C1 inhibitor (C1-INH) deficiency (hereditary angioedema type 1) caused by mutations in the C1NH gene (also called the SERPING1 gene) 14

- Hereditary angioedema with dysfunctional C1 inhibitor (hereditary angioedema type 2) caused by mutations in the C1NH gene (also called the SERPING1 gene) 14

- Hereditary angioedema with normal C1 inhibitor (nC1-INH-HAE or hereditary angioedema type 3) caused by mutations in the coagulation factor XII (F12), plasminogen, angiopoietin 1, kininogen 1 and myoferlin gene 15. Hereditary angioedema with normal C1 inhibitor (nC1-INH-HAE) was previously referred to as type 3 hereditary angioedema, but this term is obsolete and should not be used 16.

- Based on these findings, 4 additional hereditary angioedema with normal C1-INH types were defined 17, 18, 19, 20:

- Hereditary angioedema with a specific mutation in the PLG gene (HAE-PLG),

- Hereditary angioedema with a specific mutation in the ANGPT1 gene (HAE-ANGPT1),

- Hereditary angioedema with a specific mutation in the KNG1 gene (HAE-KNG1), and

- Hereditary angioedema with a specific mutation in the MYOF gene (HAE-Myoferlin).

- When no mutation is detected in families with normal C1 inhibitor (nC1-INH-HAE), the disease is known as hereditary angioedema of unknown origin (U-HAE) 14

- Based on these findings, 4 additional hereditary angioedema with normal C1-INH types were defined 17, 18, 19, 20:

Hereditary angioedema type 1 is the most common, accounting for 85 percent of cases. Type 2 occurs in 15 percent of cases, and hereditary angioedema type 3 is very rare 21.

The angioedema attacks are usually disfiguring, potentially causing severe morbidity and might be life threatening 13. Attacks vary in frequency and severity and are difficult to predict, although prodromal symptoms may precede. They generally progress over 24 hours and resolve within 2–5 days. Some members of the family often have similar symptoms 13. Hereditary angioedema is often confused with other causes of angioedema, including allergic angioedema; however, unlike histaminergic angioedema, which typically starts to swell in minutes and resolves in hours, swellings develop more slowly; do not respond well to treatment with corticosteroids, antihistamines, or adrenaline; and resolve in days (see Table 2). This confusion can sometimes lead to a delay in delivering appropriate treatment, resulting in severe consequences and even death. The swelling does not have well-defined borders, is usually not painful but bothersome, and develops owing to plasma leakage from postcapillary venules into the dermal layers of the skin. This leakage is mainly associated with the absence or dysfunction of a protein called C1-INH owing to a mutation in the SERPING1 gene 2, 22. The increase in vascular permeability that causes angioedema in hereditary angioedema is related to the mediators of the contact system or kallikrein-kinin pathway. C1-INH regulates the contact system through the inhibition of plasma kallikrein and coagulation factor FXIIa. This inhibition suppresses the formation of bradykinin. Bradykinin is a nonapeptide produced as a result of contact system activation. It binds to Bradykinin 2 receptors (B2R) on vascular endothelial cells, leading to increased vascular permeability and edema. Bradykinin concentrations increase acutely in patients with hereditary angioedema 23.

Management of hereditary angioedema involves treatment of sudden (acute) attacks and preventing attacks (prophylaxis) 3. Treatment for acute attacks in hereditary angioedema types 1 and 2 includes replacement with C1 inhibitor concentrates, a kallikrein inhibitor, or fresh-frozen plasma (by infusion). Sudden attacks involving the upper airway may involve intubation if stridor or signs of respiratory distress are present. Hereditary angioedema with normal C1 inhibitor levels (hereditary angioedema type 3) is treated similarly, however C1 inhibitor infusion is not effective. Prophylaxis may involve regular injections of C1 inhibitor concentrates, long-term androgen (male hormone) therapy, or antifibrinolytics.

The long-term outlook (prognosis) for hereditary angioedema varies depending on the frequency and location of attacks, and the severity of attacks in each person. Attacks generally continue throughout life, but the frequency of attacks can be significantly reduced with therapy.

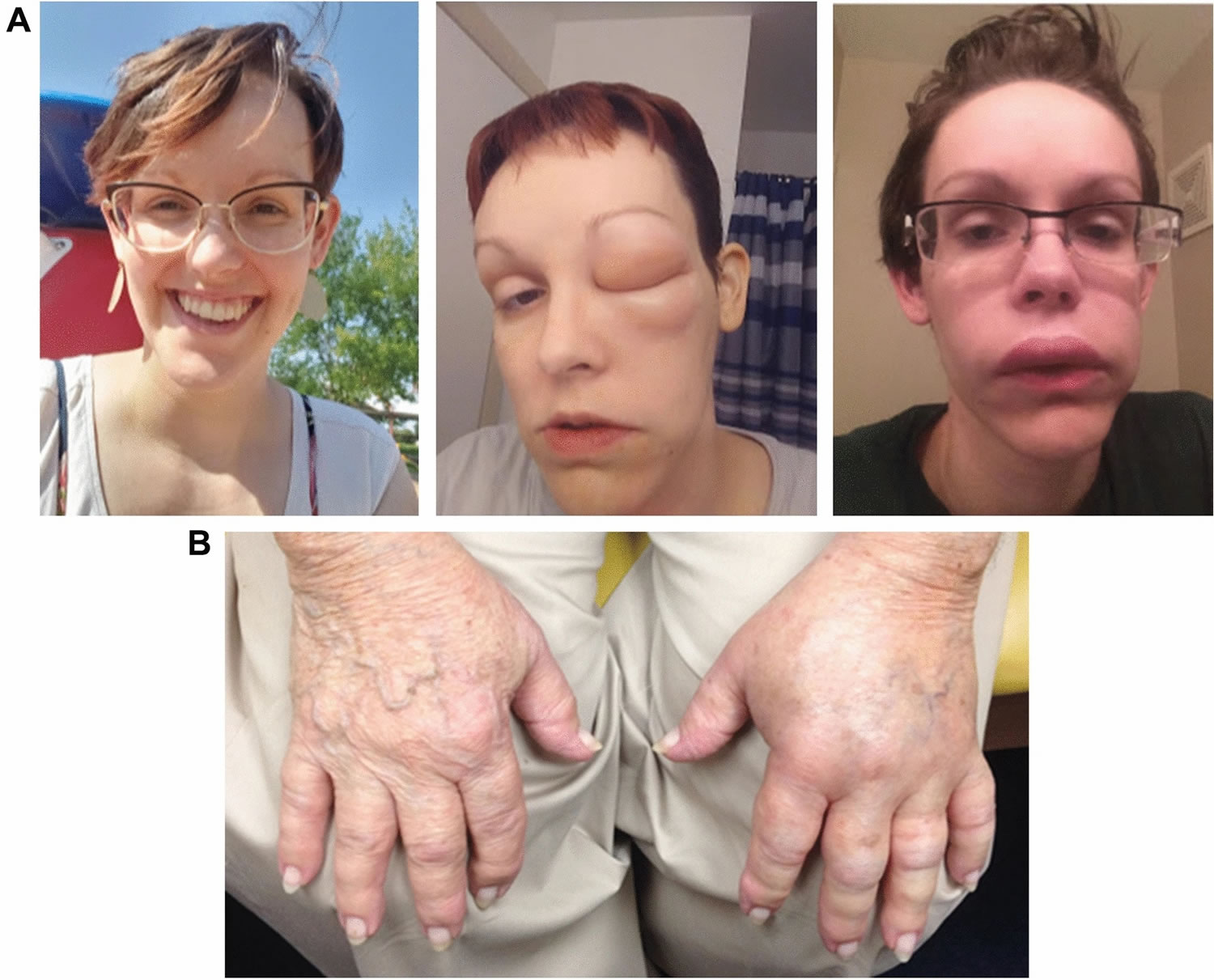

Figure 1. Hereditary angioedema

Footnotes: Photographs of hereditary angioedema attacks affecting (A) the face (baseline and during) and (B) hands

[Source 24 ]Figure 2. Angioedema eyes

Figure 3. Angioedema lips

Figure 4. Angioedema tongue

Figure 5. Hives (urticaria)

Figure 6. Erythema marginatum

Footnote: Photograph of erythema marginatum, a transient reticular rash that sometimes appears as a prodrome to hereditary angioedema attacks

[Source 24 ]What is angioedema?

Angioedema is swelling underneath the skin caused by fluid leakage from blood vessels into the surrounding skin and tissue 25, 13. There are multiple types of angioedema, including acute allergic angioedema, non-allergic drug reactions, idiopathic angioedema, acquired C1 inhibitor deficiency angioedema and hereditary angioedema (HAE). Angioedema is usually a reaction to a trigger, such as a medication or something you’re allergic to. Angioedema is most often characterized by a sudden onset or come on gradually over a few hours of short-lived swelling of the skin and mucous membranes. The nonpitting, localized swelling of the subcutaneous and mucosal tissues caused by angioedema normally lasts a few days 26. All parts of your body may be affected but swelling most often occurs around the eyes, lips, mouth, tongue, extremities, and genitalia. In severe cases the internal lining of the upper respiratory tract and intestines may also be affected causing breathing difficulties, tummy (abdominal) pain and dizziness. The swelling may be accompanied by a raised, itchy rash called hives (urticaria), which are more superficial, while angioedema affects the deeper layers of skin.

Up to 20% of people will develop hives (urticaria) at some time in their life and around one in three of these will have angioedema as well. Having angioedema on its own (without hives) is much less common. Urticaria also known as hives is the development of transient localized edema (swelling) in the dermis, characterized by itchy welts (wheals) that range in size from small spots to large blotches and often co-exists with angioedema. Wheals are usually superficial skin-colored or pale swellings, surrounded by erythema (redness).

There are three major patterns of angioedema:

- Angioedema plus hives (urticaria): the hives itch and the angioedema is itchy, hot or painful.

- Angioedema alone: itchy, hot and red swellings, often large and uncomfortable.

- Angioedema alone: skin-colored swellings, not itchy or burning, often unresponsive to antihistamines.

Angioedema eventually disappears in most people. It may reappear following infection, when under stress or for no particular reason that can be identified. Occasionally it is a recurrent problem that reappears throughout life. Angioedema is seldom caused by a serious underlying disease, nor does it make you sick or cause damage to organs such as kidneys, liver or lungs.

Angioedema isn’t normally serious, but it can be a recurring problem for some people and can very occasionally be life-threatening if it affects your breathing. Treatment can usually help keep the swelling under control.

What is urticaria?

Urticaria is the medical term for hives (very itchy raised skin reactions known as weals). Hives are red swellings of the skin that occur in groups on any part of the skin. Angioedema is a swelling similar to urticaria, but the swelling is beneath the skin rather than on the surface. Urticaria and angioedema often occur together. A weal (or wheal) is a superficial skin-colored or pale skin swelling, usually surrounded by erythema (redness) that lasts anything from a few minutes to 24 hours.

The key point when attempting to distinguish urticaria from all other rashes is answering the question, “how long do the spots last” 27. With urticaria the answer must be minutes to hours, and by definition, always less than 24 hours 28. Because urticaria is due to dilation of blood vessels caused by histamine and other mediator release from mast cells or bradykinin activation, there is no tissue damage, other than scratch damage, and basically no pathologic cellular infiltration. If there are painful lesions lasting for more than 24 hours, even if they look like “hives”, consider alternative diagnoses such as contact dermatitis or urticarial vasculitis 28.

The name urticaria is derived from the common European stinging nettle Urtica dioica. Urticaria can be acute or chronic, spontaneous or inducible.

The most common form of urticaria is called spontaneous urticaria. Spontaneous urticaria is usually divided into ‘acute’ and ‘chronic’ forms. In ‘acute’ urticaria, the episode lasts up to six weeks. Chronic or long-lasting urticaria lasts for six weeks or more.

Urticaria is caused by the release of histamine and other chemicals from cells in the skin called mast cells. Urticaria is often thought of as an allergy but, in fact, it usually results from histamine release from mast cells due to other reasons.

Allergens in food, or medicine may sometimes cause acute urticaria. For young babies, in whom urticaria is rare, cow’s milk allergy is the commonest cause. As children grow up, they may react to different foods, including nuts, fruits or shellfish if they become allergic. Bee and wasp stings can cause acute urticaria.

However, a specific reason for urticaria is often not found. Chronic spontaneous urticaria may be autoimmune, the patient’s own antibodies that release histamine from mast cells. Tests for autoimmune urticaria are not routinely available and generally do not alter treatment. When a cause cannot be found, it is called ‘idiopathic’. Weals may be set off by a physical trigger, such as cold, pressure or friction. This type of urticaria is called inducible because hives are induced by a specific stimulus and are not spontaneous.

Some people with urticaria have other conditions, such as thyroid disease or other autoimmune disorders.

Types of angioedema

Angioedema can be classified into at least four types, acute allergic angioedema, non-allergic drug reactions, idiopathic angioedema, hereditary angioedema and acquired C1 inhibitor deficiency.

Whatever the cause of angioedema, the actual mechanism behind the swelling is the same in all cases. Small blood vessels in the subcutaneous and/or submucosal tissues leak watery liquid through their walls and cause swelling. This same mechanism occurs in urticaria but just closer to the skin surface.

Table 1. Types of angioedema

| Angioedema type | Clinical features |

|---|---|

| Acute allergic angioedema |

|

| Non-allergic drug reaction angioedema (drug-induced angioedema) |

|

| Idiopathic/chronic angioedema |

|

| Hereditary angioedema |

|

Acute allergic angioedema

Acute allergic angioedema almost always occurs with urticaria within 1-2 hours of exposure to the allergen. Allergic angioedema is where the body mistakes a harmless substance, such as a certain food, for something dangerous. It releases chemicals into the body to attack the substance, which cause the skin to swell. Swellings due to allergic reactions to foods or drugs are sometimes severe and dramatic, but usually resolve within 24 hours.

Angioedema can be triggered by an allergic reaction to 14:

- certain types of food – especially nuts, shellfish, milk and eggs

- some types of medication – including some antibiotics (penicillin), aspirin and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as ibuprofen, sulfa drugs and vaccines

- insect bites, venoms and stings – particularly wasp and bee stings

- natural rubber latex – a type of rubber used to make medical gloves, catheters, balloons, contraceptive devices and condoms

- radio contrast media

Drug-induced angioedema

Drug-induced angioedema also known as non-allergic drug reaction onset may be days to months after first taking the medication. Some medicines can cause angioedema – even if you’re not allergic to the medication. The swelling may occur soon after you start taking a new medication, or possibly months or even years later.

Medications that can cause angioedema include:

- Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, such as enalapril, lisinopril, perindopril and ramipril, which are used to treat high blood pressure

- Ibuprofen and other types of NSAID painkillers

- Angiotensin-2 receptor blockers (ARBs), such as andesartan, irbesartan, losartan, valsartan and olmesartan – another medication used to treat high blood pressure

Acquired C1 inhibitor deficiency

Acquired C1 inhibitor deficiency also called acquired angioedema (AEE) is acquired C1-esterase inhibitor deficiency (C1-INH) during life rather than inherited C1-esterase inhibitor deficiency (C1-INH) like hereditary angioedema (HAE). Acquired angioedema results from a lymphoproliferative disorder such as a B-cell lymphoma (type 1) or from the development of mainly immunoglobulin G antibodies against C1-INH (type 2). C1q measurement can help to distinguish acquired angioedema from hereditary angioedema. C1q levels are normal in hereditary angioedema but low in acquired angioedema, which otherwise has a similar C1-INH/C4 profile.

Acquired C1 inhibitor deficiency is caused by:

- May be due to B-cell lymphoma or antibodies against C1 inhibitor

- Associated with lymphoproliferative disorder and autoimmune disease e.g. systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)

- Age of onset is usually over 40 years

- No family history of angioedema

Inducible angioedema

Inducible angioedema is a form of chronic inducible urticaria. Rarely vibration (vibratory angioedema) and cold stimuli can induce angioedema. Localized vibratory urticaria is also due to a vibratory stimulus and is considered distinct from vibratory angioedema.

Hereditary angioedema

Hereditary angioedema also known as HAE, hereditary angioneurotic edema or C1-esterase inhibitor deficiency (C1-INH-HAE), is a very rare and potentially life-threatening genetic disorder that is associated with recurrent attacks (also called episodes) of noninflammatory, nonpitting, self-limiting edema (swelling) affecting subcutaneous tissues and gastrointestinal and oropharyngeal mucosa without urticaria 1, 2. The frequency of attacks usually increases after puberty 3. Attacks most often affect 3 parts of the body: skin – the most common sites are the face (such as the lips and eyes), hands, arms, legs, genitals, and buttocks. Skin swelling can cause pain, dysfunction, and disfigurement, although it is generally not dangerous and is temporary. Gastrointestinal tract – the stomach, intestines, bladder, and/or urethra may be involved. This may cause symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal pain; abdominal angioedema attacks can lead to unnecessary surgery and delay in diagnosis, as well as to narcotic dependence due to severe pain; and cutaneous attacks can be disfiguring and disabling 4. Upper airway (such as the larynx and tongue) – this can cause upper airway obstruction and asphyxiation. The majority of attacks affecting the airway resolve before complete airway obstruction. Attacks may involve one area of the body at a time, or they may involve a combination of areas. They always go away on their own but last from 2 to 4 days. Attacks generally continue throughout life, but the frequency of attacks can be significantly reduced with therapy. While people with hereditary angioedema have reported various triggers of attacks, emotional stress, physical stress, and dental procedures are the most commonly reported triggers.

Idiopathic angioedema

Idiopathic angioedema is when the cause of angioedema is unknown or unidentified. One theory is that an unknown problem with the immune system might cause it to occasionally misfire. Idiopathic angioedema is frequently chronic and relapsing and usually occurs with urticaria.

Certain triggers may lead to swelling, such as:

- anxiety or stress

- minor infections

- hot or cold temperatures

- strenuous exercise

In very rare cases, the swelling may be associated with other medical conditions, such as lupus or lymphoma (cancer of the lymphatic system).

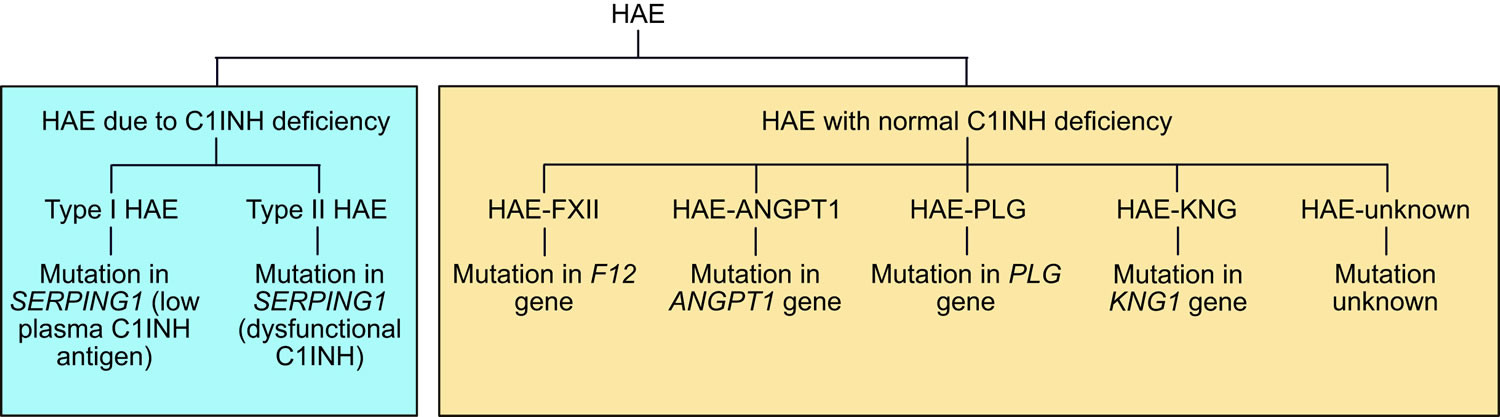

Types of hereditary angioedema

Hereditary angioedema can be broadly divided into 2 fundamental types: hereditary angioedema due to C1 esterase inhibitor deficiency (HAE-C1-INH) or hereditary angioedema with normal C1 esterase inhibitor (nC1-INH-HAE) (Figure 5). Hereditary angioedema due to C1 esterase inhibitor deficiency (HAE-C1-INH) is further divided into 2 subtypes: type 1 hereditary angioedema, characterized by deficient levels of C1INH protein and function; and type 2 hereditary angioedema, characterized by the normal level of C1INH protein that is dysfunctional, resulting in diminished C1INH functional activity 29. Both type 1 and type 2 hereditary angioedema are caused by mutations in the gene that encodes C1INH (SERPING1) 7. The estimated prevalence of type 1 and type 2 hereditary angioedema is 1 per 50,000, suggesting that there are approximately 6000 affected individuals in the United States.

Hereditary angioedema with normal C1 esterase inhibitor (nC1-INH-HAE) was first described in 2000 7 and is not as well understood as hereditary angioedema due to C1 esterase inhibitor deficiency (HAE-C1-INH). At the current time, there are 5 subtypes of hereditary angioedema with normal C1 esterase inhibitor (nC1-INH-HAE) based on the underlying mutation 30:

- Hereditary angioedema with a specific coagulation F12 (FXII) gene mutation (HAE-FXII) is due to mutations in F12, the gene encoding coagulation FXII 31

- Hereditary angioedema with a specific plasminogen gene mutation (HAE-PLG) is due to mutations in PLG, the gene encoding plasminogen 32

- Hereditary angioedema with a specific angiopoietin-1 gene mutation (HAE-ANGPT1) is due to mutations in ANGPT1, the gene encoding angiopoietin-1 33

- Hereditary angioedema with a specific kininogen-1 gene mutation (HAE-KNG1) is due to a mutation in the kininogen 1 gene 34

- Hereditary angioedema where the genetic background of the disease is still unknown (HAE-unknown) represents patients with hereditary angioedema with normal C1 esterase inhibitor (nC1-INH-HAE) for whom the responsible mutation has not yet been defined.

The overall prevalence of hereditary angioedema with normal C1 esterase inhibitor (nC1-INH-HAE) is not known. Hereditary angioedema with a specific coagulation F12 (FXII) gene mutation (HAE-FXII) comprises approximately 20% of hereditary angioedema with normal C1 esterase inhibitor (nC1-INH-HAE) cases in Europe but for reasons that are not clear is exceedingly rare in the United States 35.

Figure 7. Types of hereditary angioedema

[Source 16 ]Table 2. Types of hereditary angioedema

| Hereditary angioedema type | Gene | Nucleotide change | Protein change | Chromosome | First described by | Methods used |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hereditary angioedema due to C1 esterase inhibitor deficiency (HAE-C1-INH) | SERPING1 | Numerous | Numerous | 11 | Stoppa-Lyonnet et al. 36 | Southern blot analysis, linkage analysis |

| Hereditary angioedema with a specific coagulation F12 (FXII) gene mutation (HAE-FXII) | F12 | c.983C > A | p.T328K | 5 | Dewald and Bork 37 | Candidate gene, Sanger sequencing, linkage analysis |

| c.983C > G | p.T328R | 5 | Dewald and Bork 37 | Candidate gene, Sanger sequencing, linkage analysis | ||

| c.971_1018 + 24del72 | Indel | 5 | Bork et al. 38 | Sanger sequencing, linkage analysis | ||

| c.892_909dup | dup p.298_303 | 5 | Kiss et al. 39 | Sanger sequencing, linkage analysis | ||

| Hereditary angioedema with a specific plasminogen gene mutation (HAE-PLG) | PLG | c.988A > G | p.K330E | 6 | Bork et al. 32 | Whole exome sequencing, linkage analysis, Sanger sequencing |

| Hereditary angioedema with a specific angiopoietin-1 gene mutation (HAE-ANGPT1) | ANGPT1 | c.807G > T | p.A119S | 8 | Bafunno et al. 33 | Whole exome sequencing, linkage analysis |

| Hereditary angioedema with a specific kininogen-1 gene mutation (HAE-KNG1) | KNG1 | c.1136 T > A | p.M379K | 3 | Bork et al. 34 | Whole exome sequencing, linkage analysis, Sanger sequencing |

| Hereditary angioedema with a specific myoferlin gene mutation (HAE-Myoferlin) | MYOF | c.651G > T | p.R217S | 10 | Ariano et al. 40 | Whole exome sequencing, linkage analysis |

| Hereditary angioedema where the genetic background of the disease is still unknown (HAE-unknown) | nia | na | na | na | na | na |

Abbreviations: ANGPT1 = angiopoietin-1 gene; bp = base pairs; C1-INH = C1 esterase inhibitor; del = deletion; dup = duplication; F12 = coagulation factor XII gene; FXII = coagulation factor XII protein; KNG1 = kininogen-1 gene; na = not applicable; ni = not identified; MYOF = myoferlin gene; PLG = plasminogen gene

[Source 15 ]Hereditary angioedema type 1

Hereditary angioedema type 1 is the most common form which affects around 85% of people with hereditary angioedema – blood tests show low quantitative levels of C1-inhibitor protein.

Hereditary angioedema type 2

Hereditary angioedema type 2 affects the other 15% of people with hereditary angioedema who have normal or elevated levels of C1-inhibitor protein, but the protein does not function properly.

Hereditary angioedema type 3

Hereditary angioedema type 3 is an extremely rare form of hereditary angioedema where the levels of C1-inhibitor protein are normal (nC1-INH-HAE) – caused by mutations in the coagulation factor XII (F12), plasminogen, angiopoietin 1, kininogen 1 and myoferlin gene 15. Based on these findings, 4 additional hereditary angioedema with normal C1-inhibitor protein (C1-INH) types were defined 17, 18, 19, 20:

- Hereditary angioedema with a specific mutation in the PLG gene (HAE-PLG),

- Hereditary angioedema with a specific mutation in the ANGPT1 gene (HAE-ANGPT1),

- Hereditary angioedema with a specific mutation in the KNG1 gene (HAE-KNG1), and

- Hereditary angioedema with a specific mutation in the MYOF gene (HAE-Myoferlin).

Hereditary angioedema cause

Mutations in the SERPING1 gene cause hereditary angioedema type 1 and type 2. The SERPING1 gene provides instructions for making the C1 inhibitor (C1-INH) protein, which is important for controlling inflammation. C1 inhibitor blocks the activity of certain proteins that promote inflammation. Mutations that cause hereditary angioedema type 1 lead to reduced levels of C1 inhibitor (C1-INH) in the blood, while mutations that cause type 2 result in the production of a C1 inhibitor (C1-INH) that functions abnormally. Without the proper levels of functional C1 inhibitor (C1-INH), excessive amounts of a protein fragment (peptide) called bradykinin are generated. Bradykinin promotes inflammation by increasing the leakage of fluid through the walls of blood vessels into body tissues. Excessive accumulation of fluids in body tissues causes the episodes of swelling seen in individuals with hereditary angioedema type 1 and type 2.

Mutations in the F12 gene are associated with some cases of hereditary angioedema type 3. This gene provides instructions for making a protein called coagulation factor XII. In addition to playing a critical role in blood clotting (coagulation), factor XII is also an important stimulator of inflammation and is involved in the production of bradykinin. Certain mutations in the F12 gene result in the production of factor XII with increased activity. As a result, more bradykinin is generated and blood vessel walls become more leaky, which leads to episodes of swelling in people with hereditary angioedema type 3.

The cause of other cases of hereditary angioedema type 3 remains unknown. Mutations in one or more as-yet unidentified genes may be responsible for the disorder in these cases.

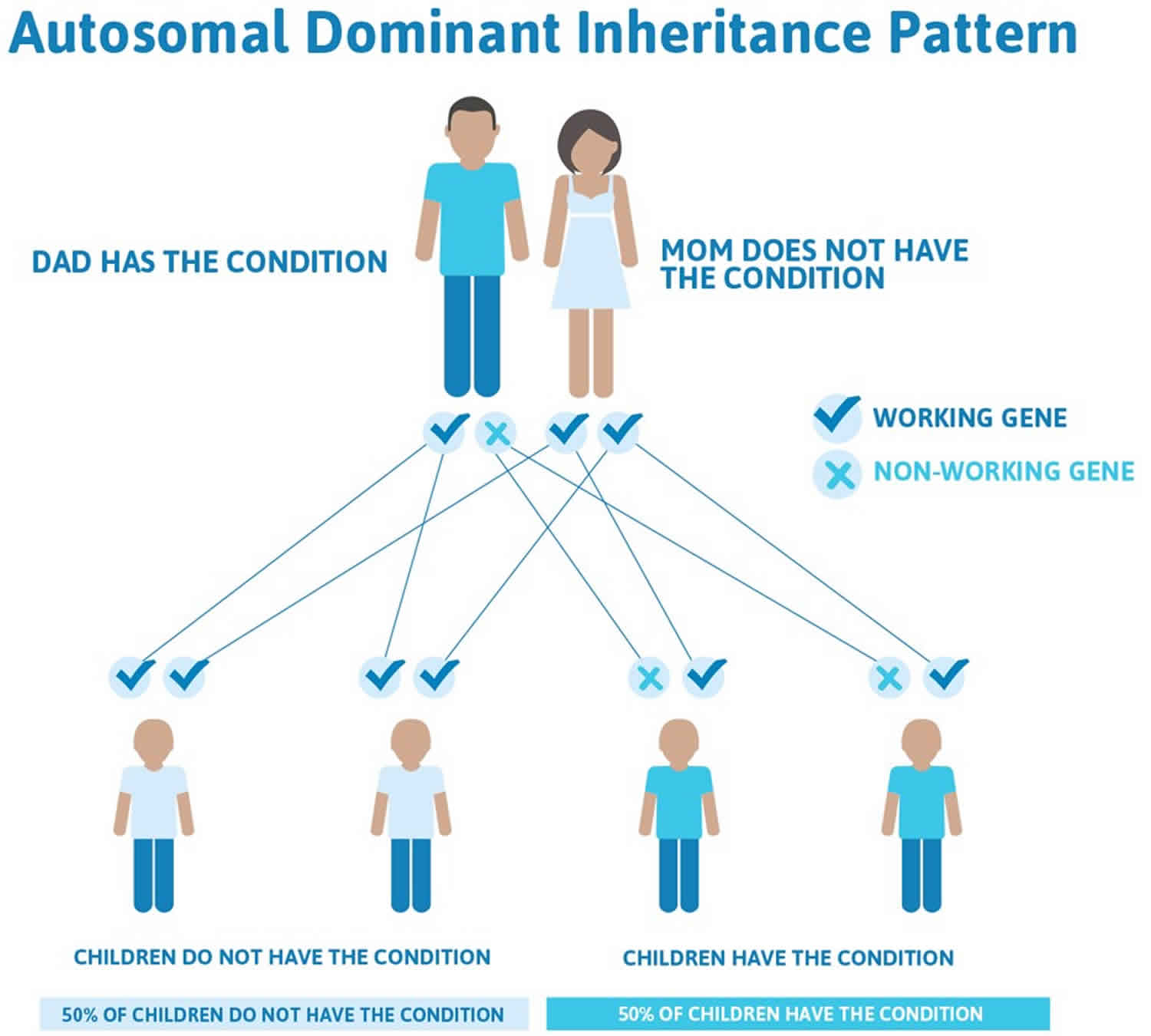

Hereditary angioedema inheritance pattern

Hereditary angioedema is inherited as an autosomal dominant trait. Genetic diseases are determined by two genes, one received from the father and one from the mother.

Autosomal dominant genetic disorders occur when only a single copy of an abnormal gene is necessary for the appearance of the disease.

Hereditary angioedema is an autosomal-dominant condition, meaning if one parent has the abnormal gene that codes for angioedema, half of their children will inherit the condition (their children have a 50% possibility of inheriting this disease regardless of the sex of the resulting child) 41. However, less commonly, there may be no family history of the condition, as hereditary angioedema may occur “spontaneously”. Around 25% of hereditary angioedema cases result from people who have a spontaneous mutation (de novo mutations) of the particular gene at conception. Subsequently, these people can pass the defective gene to their children 42.

Figure 8. Hereditary angioedema autosomal-dominant inheritance pattern

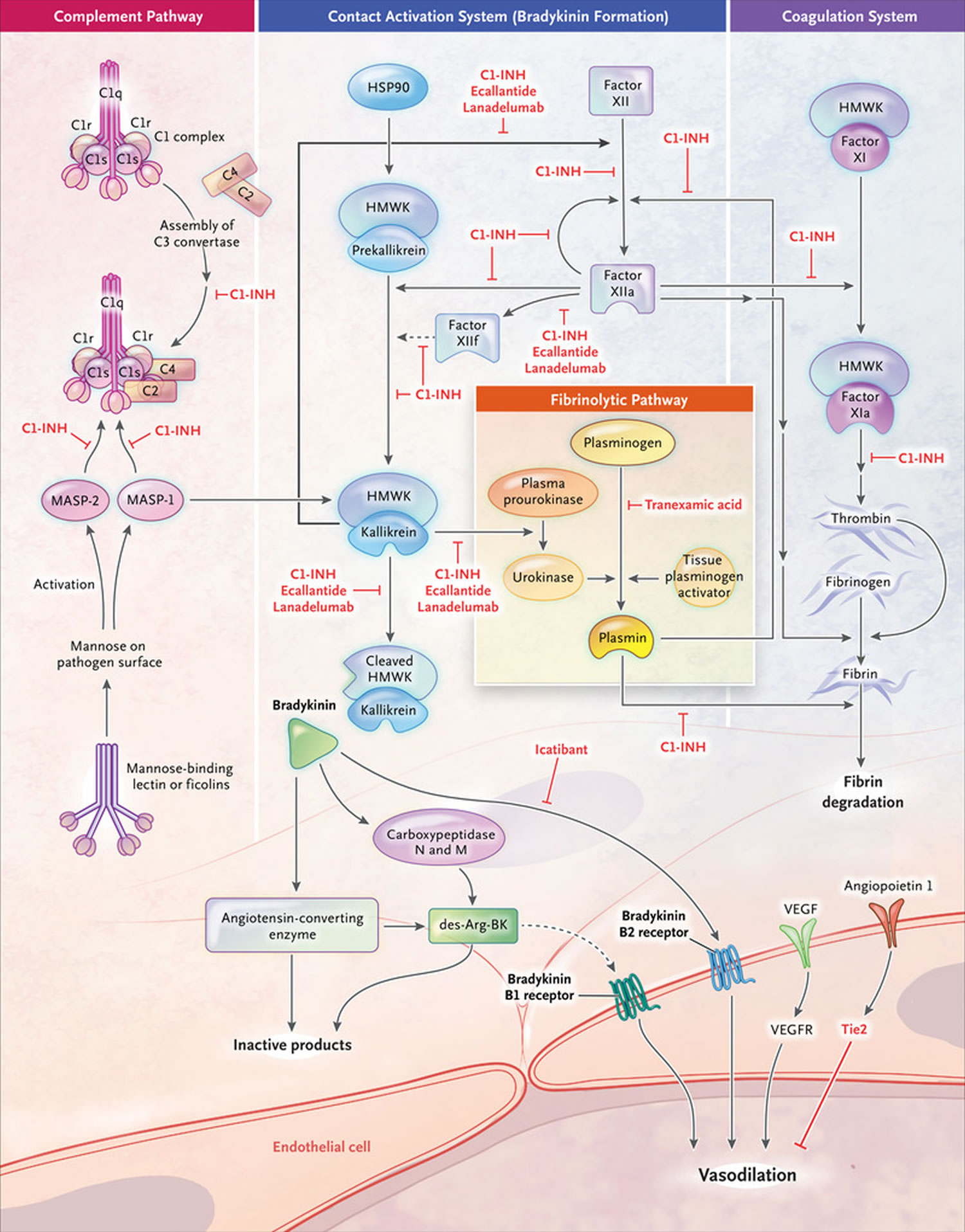

Pathophysiology of hereditary angioedema

C1 inhibitor (C1-INH) protein is a member of the serpin family of serine protease inhibitors, is a major regulator of the complement, contact, and coagulation cascades through inhibition of several complement proteases (C1r, C1s, and mannose-binding lectin-associated serine protease 1 and 2 [MASP]), contact system proteases (plasma kallikrein and coagulation factor XIIa), and coagulation factors (XIa and XIIa) 43. In hereditary angioedema, a deficiency of functional C1 inhibitor (C1-INH) allows for uncontrolled activation of these cascades, resulting in increased vascular permeability and the classic symptoms of swelling 9.

The primary mediator of vascular permeability in hereditary angioedema is bradykinin, a nonapeptide generated through activation of the complement system that binds to receptors (the B2 receptor) on vascular endothelial cells 9. Bradykinin is thought to promote vascular permeability by loosening the junctions between vascular endothelial cells through phosphorylation of vascular endothelial cell cadherin 9. Bradykinin is the primary mediator of swelling in hereditary angioedema. It is important for normal homeostasis, normal immune responses, inflammation, vascular tone and vascular permeability. Angioedema is primarily mediated through the B2 bradykinin receptor causing increased permeability. Experiments in C1INH-deficient mice demonstrate a persistent increase in vascular permeability mediated by enhanced bradykinin signaling that is reversible with administration of a B2 receptor inhibitor 44. By contrast, mice deficient in both C1 inhibitor (C1-INH) and B2 receptor show no increased vascular permeability 44. Expression of bradykinin is regulated by kallikrein in the contact cascade 45. B2 receptor and plasma kallikrein are important new drug targets in hereditary angioedema. In 2009, ecallantide (Kalbitor), a potent and specific inhibitor of plasma kallikrein, became the second agent (following Berinert) to be FDA-approved for the treatment of acute hereditary angioedema attacks, followed in 2011 by the B2 receptor antagonist icatibant (Firazyr) 46.

Figure 9. Hereditary angioedema pathophysiology

Footnotes: The principal mediator involved in hereditary angioedema during episodes of swelling is bradykinin, a byproduct of the plasma contact system. The C1 inhibitor (C1-INH) plays a significant role in the complement cascade, coagulation, and contact systems. As its name implies, it has an important inhibiting effect on the major proteases in these pathways, including activated Hageman factor, kallikrein, and plasmin, as illustrated in the figure above. The C1 inhibitor (C1-INH) is ultimately responsible for regulating the production of bradykinin. In this manner, episodes of trauma or stress can activate contact and complement pathways. In the setting of C1–inhibitor deficiency (type 1 hereditary angioedema) or C1–inhibitor dysfunction (type 2 hereditary angioedema), increased levels of bradykinin lead to recurrent episodes of angioedema. Hereditary angioedema with normal C1 inhibitor has been associated with defects in the coagulation cascade, although its underlying pathophysiology remains to be determined.

[Source 47 ]Hereditary angioedema symptoms

The characteristic symptom of hereditary angioedema is recurrent episodes of swelling of affected areas due to the accumulation of excessive body fluid (edema). The areas of the body most commonly affected include the hands, feet, eyelids, lips, and/or genitals. Edema may also occur in the mucous membranes that line the respiratory and digestive tracts, which is more common in people with hereditary angioedema than in those who have other forms of angioedema (i.e., acquired or traumatic). People with hereditary angioedemar typically have areas of swelling that are hard and painful, not red and itchy (pruritic). A skin rash (urticaria) rarely is present. About 25% of people with hereditary angioedema experience a flat, non-itching red rash that often occurs before or during an hereditary angioedema attack.

Symptoms associated with swelling in the digestive system (gastrointestinal tract) include nausea, vomiting, acute abdominal pain, and/or other signs of obstruction. Edema of the throat (pharynx) or voice-box (larynx) can result in pain, difficulty swallowing (dysphagia), difficulty speaking (dysphonia), noisy respiration (stridor), and potentially life-threatening asphyxiation.

The symptoms of hereditary angioedema may recur and can become more severe. A number of possible attack triggers have been proposed in hereditary angioedema, including exposure to cold, minor trauma, dental procedures, prolonged sitting or standing, exposure to certain foods, medications (eg, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, estrogen-containing contraceptives, hormone replacement therapies), chemicals, infection, viral illness, severe pain and emotional stress 41. However, many attacks occur without an obvious trigger, and the same trigger may not always provoke an attack in a specific individual 7. Elevated levels of female sex hormones have been linked to edema attacks in women in all 3 hereditary angioedema subtypes 48. Case studies have documented both initiation of and exacerbations of hereditary angioedema symptoms in women during puberty and after starting estrogen-containing oral contraceptives or hormone replacement therapy (HRT) 49.

In 1 study, approximately two-thirds of women with hereditary angioedema (either type 1 or hereditary angioedema with normal C1 inhibitor [hereditary angioedema type 3]) experienced an initial edema attack or worsening of both frequency and severity of attacks after starting oral contraceptives or HRT 49. Changing the formulation of the oral contraceptive had no effect; in a number of cases the attacks continued even when oral contraception was stopped altogether 49. Like the disease course, symptoms of hereditary angioedema are quite consistent. Nearly all patients suffer from skin swelling and recurrent abdominal pain; laryngeal edema attacks by contrast are rare but will occur in 50% of patients with hereditary angioedema at some time in their lives. Attacks are often preceded by nonerythematous rash (erythema marginatum), tingling sensations, anxiety, mood changes, or exhaustion. Symptoms gradually worsen over the first 24 hours and then slowly resolve, usually within 48 to 72 hours, although swelling sometimes persists for up to 5 days 48. While attacks typically involve a single site, some patients may have simultaneous or closely spaced episodes of cutaneous and abdominal involvement 48.

Cutaneous edema

Skin swelling, most commonly affecting the extremities, is the defining feature of hereditary angioedema in the vast majority of patients—upper extremities more than lower—followed by the face and genitals and, more rarely, the trunk and neck 6. In a retrospective analysis by Bork et al 6, recurrent skin swelling occurred in 201 of the 209 patients observed, of whom 196 (97.5%) had swelling of the extremities. Skin edema in hereditary angioedema is nonpitting and nonpruritic; blisters and compartment syndromes may accompany particularly severe cases 6. Typically, 1 site is involved, with the edema gradually spreading then receding over a period of days 6. Approximately one-third of cutaneous hereditary angioedema attacks are preceded by erythema marginatum, a nonprurutic, serpiginous rash that produces a map-like pattern on the skin 41. This symptom occurs more frequently in pediatric patients and is a potential diagnostic pitfall, as it can be mistaken for similar rashes accompanying childhood viral or bacterial illnesses, or may be misdiagnosed as urticaria 41, 50.

Abdominal symptoms

Recurrent abdominal pain resulting from edema of the gastrointestinal wall is reported in 70% to more than 90% of patients with hereditary angioedema 6. Symptoms can range from mild, intermittent abdominal discomfort to severe colicky pain accompanied by vomiting and/or diarrhea. Cases of hypovolemic shock resulting from fluid loss, plasma extravasation, and vasodilation have been reported in severe abdominal attacks 48. Abdominal episodes of hereditary angioedema can mimic a number of other conditions, including gastroenteritis, acute appendicitis, mesenteric lymphadentitis, and intussusception, among several less common conditions, which can lead to unnecessary emergency abdominal surgery 48. Abdominal ultrasound and computer-assisted tomography scans help with the differential diagnosis by detecting free peritoneal fluid, edematous intestinal mucosa, and liver structure abnormalities, but these signs are not clearly specific for angioedema 41. Hemoconcentration and leukocytosis are sometimes seen in association with abdominal hereditary angioedema attacks 48.

Laryngeal edema

Laryngeal edema is a rare but potentially fatal clinical manifestation of hereditary angioedema. While less than 1% of all swelling episodes involve the larynx, approximately half of all patients with hereditary angioedema have a laryngeal attack at some point in their lives 48. Before the availability of agents to specifically treat hereditary angioedema, mortality associated with laryngeal edema was approximately 30% 48. Data from 123 patients suggested that, on average, patients experienced their first episode of laryngeal edema at a later age (26.2 years) compared with their first skin swelling (15.4 years) or abdominal pain attack (16.2 years) 51. However, laryngeal edema has been reported in patients as young as 3 years 51. Pediatric patients present a particular diagnostic challenge because laryngeal edema may be misdiagnosed as allergic asthma or epiglottitis 41. Further, compared with adults, asphyxiation in children may develop more quickly due to their smaller airway diameter.20 An important diagnostic clue is that standard medications (ie, antihistamines, corticosteroids, and epinephrine) normally effective for alleviating acute airway edema in children are generally ineffective for laryngeal hereditary angioedema attacks 41.

Clinical symptoms of laryngeal edema include voice changes (eg, hoarseness or deepening of the voice), a feeling of tightness or a lump in the throat, and dysphagia 6. Patients with advanced swelling often have aphonia (ie, loss of voice) and fear of asphyxiation with substantial anxiety. Upper airway obstruction is usually caused by laryngeal and glottal edema 51. In some patients, laryngeal edema may be accompanied by swelling of the soft palate, including the uvula and the tongue 6. The time from onset of laryngeal edema to maximal swelling has been reported to range from 8 to 12 hours, but may be shorter or considerably longer 51. Local trauma, such as dental work, endoscopy, and intubation during general anesthesia, has been reported to trigger laryngeal swelling in some patients with hereditary angioedema 51.

Other symptoms

Less common but clinically important manifestations of hereditary angioedema may include neurological, pulmonary, renal, urinary, and musculoskeletal symptoms, many of these having been only recently identified 6. Edema of the soft palate, uvula, and, rarely, the tongue has occurred, both separately and in conjunction with laryngeal edema. Severe headache accompanied by other neurological symptoms, such as vision disturbances, impaired balance, and disorientation, has recently been reported in patients with hereditary angioedema 6. Recurrent pulmonary and esophageal symptoms have been documented in a number of patients, including chest pain, shortness of breath, and severe pain while swallowing food 6. Because the symptoms resolved relatively rapidly after administration of C1INH concentrate, they were suggestive of an underlying hereditary angioedema etiology rather than a surgical emergency. Pulmonary involvement in hereditary angioedema is controversial and the underlying pathology is not well understood 6. Urinary symptoms of hereditary angioedema may include difficulty of urination, pain while urinating, and bladder spasm. Pain and swelling of the shoulder and hip joints and muscles of the neck, back, and arms has been reported in some patients 6.

Hereditary angioedema diagnosis

The diagnosis of hereditary angioedema should be considered in individuals presenting with recurrent and transient episodes cutaneous angioedema attacks, abdominal pain, or upper airway angioedema, together with a family history, particularly if the swelling is not responsive to antihistamines or steroid therapy. The diagnosis should also be considered if swelling episodes are not associated with hives. The absence of a family history, however, is not a disqualifying feature, since up to 25% of HAE patients have spontaneous C1INH mutations 52. Published guidelines for the diagnosis of hereditary angioedema are available 53.

The differential diagnosis of hereditary angioedema includes the following:

- Immediate hypersensitivity (immunoglobulin E–mediated) reactions;

- Urticaria/angioedema syndromes (including idiopathic angioedema);

- ACE inhibitor–induced angioedema; and

- Acquired angioedema syndromes associated with underlying malignant or rheumatologic disease.

Unlike hereditary angioedema, the main mediator of angioedema in the setting of hypersensitivity reactions or urticaria/angioedema syndromes is histamine, not bradykinin. Bradykinin is responsible for recurrent episodes of swelling seen in hereditary angioedema and in acquired angioedema and ACE inhibitor–induced angioedema syndromes 54.

The diagnosis of hereditary angioedema should be confirmed by laboratory tests. Screening for hereditary angioedema due to C1-esterase inhibitor deficiency (C1-INH-HAE) is based on the measurement of plasma levels of complement factor 4 (C4) levels, which is low in most cases 55. Measurement of complement factor 4 (C4) is generally considered a valuable, cost-effective test for hereditary angioedema in patients with unexplained recurrent edema because normal C4 levels, particularly at the time of a swelling episode, almost always indicate an alternate etiology 56. Some clinicians, however, advocate testing for C1-esterase inhibitor (C1INH) regardless of C4 levels to avoid possible false negatives—1 study of diagnostic assays for hereditary angioedema reported a sensitivity of low C4 of just 81% 57. Despite the best available evidence, 1 recent survey of US allergists/immunologists and primary care physicians who treat hereditary angioedema found that only 64% of respondents used C4 testing to aid in the diagnosis of hereditary angioedema 56. Almost 84% reported that they used C1INH level and function testing 56.

Virtually all patients with hereditary angioedema have persistent low levels of antigenic C4, although about 2% of patients have been reported to have normal C4 levels between edema attacks 58. Given that cases with normal C4 levels have been described, joint assessment of serum antigenic C4 and C1-esterase inhibitor (C1-INH) levels and C1 esterase inhibitor (C1-INH) function is advised 55. Functional C1INH is a specialized test and should be obtained from an experienced laboratory to avoid sample mishandling or misinterpretation 58. A normal C4 and functional C1INH result rules out both type 1 and type 2 hereditary angioedema, but does not rule out hereditary angioedema with normal C1INH (hereditary angioedema type 3) 58. At this point, there is no validated assay for diagnosing this type of hereditary angioedema. A minority of patients with normal C1INH (hereditary angioedema type 3) have mutations in genes encoding coagulation factor XII; testing for this mutation may have some utility in women with recurrent, unexplained edema and an established family history of hereditary angioedema 59.

C1q measurement can help to distinguish acquired angioedema (AEE) from hereditary angioedema (HAE). C1q levels are normal in hereditary angioedema but low in acquired angioedema, which otherwise has a similar C1-INH/C4 profile. The diagnosis should be confirmed by screening for the C1NH or SERPING1 gene 55. De novo mutations can be present in up to 25% of cases 55.

The vast majority of patients found to have C1 esterase inhibitor deficiency have hereditary angioedema (HAE), approximately 10% are acquired angioedema (AAE) and can be secondary to lymphoproliferative disease or autoimmune disorders. 50% of cases of hereditary angioedema (HAE) start before puberty but onset can be in adult life. Acquired angioedema (AAE) starts in adult life.

Table 3. Criteria for the diagnosis of hereditary angioedema

| Weight | Criteria |

|---|---|

| Hereditary angioedema with C1 inhibitor (C1-INH) deficiency | |

| Required | A history of recurrent angioedema in the absence of concomitant urticaria and no concomitant use of medication known to cause angioedema |

| Required | Low (<50% of normal) C1INH antigenic or functional level |

| Required | Low C4 level (either at baseline or during an attack) |

| Supportive | Demonstration of a pathologic SERPING1 mutation (not required for diagnosis) |

| Family history of recurrent angioedema | |

| Age of symptom onset <40 | |

| Hereditary angioedema with normal C1 inhibitor (nC1-INH-HAE) | |

| Required | A history of recurrent angioedema in the absence of concomitant urticaria and no concomitant use of medication known to cause angioedema |

| Required | Documented normal or near normal C4, C1-INH antigen, and C1-INH function |

| Either (at least 1 required) | (1) Demonstration of a mutation associated with the disease; OR (2) A positive family history of recurrent angioedema and documented lack of efficacy of high-dose antihistamine therapy (ie, cetirizine at 40 mg/d or the equivalent) for at least 1 mo or an interval expected to be associated with 3 or more attacks of angioedema, whichever is longer |

| Supportive | (1) A history of rapid and durable response to a bradykinin-targeted medication; AND (2) Predominant documented visible angioedema; or in patients with predominant abdominal symptoms, evidence of bowel wall edema documented by CT or MRI |

Abbreviations: C1-INH = C1 inhibitor; CT = computed tomography; HAE = hereditary angioedema; HAE-C1INH = hereditary angioedema due to a deficiency of C1INH; HAE-nl-C1INH = hereditary angioedema with normal C1INH; MRI = magnetic resonance imaging.

[Source 16 ]Prenatal and postnatal diagnosis

As hereditary angioedema is a genetic disorder transmitted in an autosomal dominant fashion, the offspring of a parent with hereditary angioedema have a 50% chance of inheriting the disease 41. Prenatal genetic testing for hereditary angioedema is requested rarely and is only indicated if the mutation of the affected parent is known 60. Material for genetic testing is obtained from a chorionic villus sample after 10 weeks or amniocentesis after 15 weeks 60. It is generally considered impractical to test for hereditary angioedema in the prenatal setting because a mutation is not always detected, the same mutation may be associated with different phenotypes, and the severity of the disease is not predictable 41.

For infants with an affected parent, testing for antigenic and functional C1INH is first performed at the age of 6 months or later, when complement levels typically reach adult values 41. As false positive or false negative C1INH results can occur in infants under 1 year of age, repeat testing at a later age (usually at 1 year) is indicated to confirm the diagnosis 41. C4 levels typically reach adult values between the ages of 2 and 3 years 60. Genetic testing can be useful for establishing a diagnosis of hereditary angioedema in asymptomatic children for whom C1INH and C4 assay results are equivocal 41.

Diagnosis of hereditary angioedema in symptomatic children may be impeded by a negative family history, resulting in misdiagnosis. Conversely, a diagnosis of hereditary angioedema in children has sometimes led to screening and identification of the disorder in a previously undiagnosed parent 41.

Delayed diagnosis of hereditary angioedema

Diagnostic delays in patients with hereditary angioedema have decreased substantially over the past few decades—in 1976 the average time to diagnosis from onset of symptoms was reported to be 21 years 61. Even today, however, the majority of US physicians estimate that most patients experience symptoms for an average of 7 years before a definitive diagnosis is made 62 and a few patients completely slip through the cracks. A recent case report from Texas described a 57-year-old man with previously undiagnosed hereditary angioedema who started experiencing symptoms in his teens—a diagnostic delay of about 40 years 63. While this case is clearly an outlier, in the Spanish hereditary angioedema registry study from 2005, the average time to diagnosis from symptom onset was still more than 10 years 64. A web-based survey of US physicians conducted in 2009 to 2010—The Surveillance Project on Hereditary Edema—reported an average time to diagnosis ranging from 0 to 6 months (5.8%) to more than 10 years (5.8%) 62. Less than 38% of patients with hereditary angioedema were diagnosed within 1 to 3 years from the first appearance of symptoms 62.

Delays in the diagnosis of hereditary angioedema can have serious consequences, including impaired quality of life, lost productivity and income, depression, unnecessary and/or inappropriate medical procedures, and more frequent utilization of health resources leading to increased healthcare costs 63. An online survey of 63 patients with hereditary angioedema conducted in 2004 found that patients averaged 4.7 emergency department (ED) visits each year; nearly 21% received treatment for anaphylaxis in the ED 65. Unnecessary abdominal surgery was not uncommon in patients with undiagnosed hereditary angioedema, particularly if severe abdominal pain was the presenting or predominant symptom 66. Appendectomy and exploratory diagnostic procedures, such as colonoscopy, were common procedures 66.

Hereditary angioedema treatment

At the present time hereditary angioedema cannot be cured, although scientists are working on gene therapy which will result in exciting possibilities for the future. Patients with hereditary angioedema should be counselled to avoid agents that may precipitate attacks such as an ACE inhibitor or estrogen. Stress is thought to be a trigger for attacks, so stress reduction or management may also be advised 7.

It is important to note that acute hereditary angioedema attacks do NOT respond to antihistamines, corticosteroids or adrenaline.

Currently there are modern treatments available that are divided into three areas:

- Treatment of acute hereditary angioedema attack 58

- Long-term prophylaxis to prevent hereditary angioedema attacks in the first place

- Short-term prophylaxis (eg, for a surgical procedure). Some dental and surgical procedures can be dangerous for people with hereditary angioedema, so it is important that protective treatment is used beforehand to limit the risk of hereditary angioedema attacks.

In 2008, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved Cinryze, a C1-esterase inhibitor therapy, for routine prevention (prophylaxis) of attacks of spontaneous swelling (angioedema) in adolescents and adults with hereditary angioedema. This is the first drug approved for this purpose in the U.S.

In 2009, FDA approved Berinert, a C1-esterase inhibitor therapy that is delivered intravenously, to treat acute abdominal attacks and facial or laryngeal swelling associated with hereditary angioedema in adults and adolescents. It is a protein product derived from human plasma. In 2016, FDA approved Berinert as the first and only pediatric treatment for hereditary angioedema. Also in 2009, FDA approved Kalbitor (the subcutaneous kallikrein inhibitor ecallantide) to treat sudden and potentially life-threatening fluid buildup related to hereditary angioedema. Kalbitor is a liquid that is intended to be injected under the skin of people age 16 and older with hereditary angioedema.

In 2014, FDA approved Ruconest, a recombinant C1-esterase inhibitor for the treatment of acute attacks in adult and adolescent patients with hereditary angioedema.

In 2017, FDA approved Haegarda (C1-esterase inhibitor) for administration under the skin to prevent hereditary angioedema attacks.

Most recently, in 2020, FDA approved Orladeyo (berotralstat) to prevent attacks in patients 12 years of age and older with hereditary angioedema 67. Orladeyo is an oral capsule taken one time per day. The most commonly reported adverse events in patients taking berotralstat 150 mg once daily were upper respiratory tract infection (30.00%), abdominal pain (22.50%), diarrhea (15.00%), nausea (15.00%), and vomiting (15.00%), and, overall, gastrointestinal events were reported in 50% of patients in this dose group 24.

Icatibant (Cipla or Firazyr) generic brand of bradykinin receptor antagonist (BDKRB2 antagonist) approved for treating acute hereditary angioedema attacks in patients 2 years and older. Icatibant is delivered by subcutaneous injection and is approved for self-administration.

The various treatment options should be discussed with your clinical immunology/allergy specialist to enable you to have the most appropriate treatment for your circumstances.

To avoid episodes of angioedema associated with surgery, dental work, and similar stresses, short-term treatment is suggested before surgery or dental procedures. Patients should discuss options with their physicians.

In acute attacks with the danger of severe airway swelling and obstruction, it is essential to maintain or establish an airway. A temporary surgical opening in the throat (tracheotomy) may be created and oxygen may have to be supplied.

Treatment of acute attacks

The goal of acute therapy for hereditary angioedema is to minimize morbidity and prevent mortality from an ongoing angioedema attack. The ability to treat episodes of swelling “on-demand” has been a critical advance in accomplishing this objective 68. Improved understanding of the pathophysiologic mechanism of swelling in Hereditary angioedema with C1 inhibitor (C1-INH) deficiency has catalyzed the development and approval of 4 specific products for on-demand treatment (Table3), each of which has been shown in randomized controlled studies to be effective and safe 69, 45, 70, 71. Subsequent open-label extension data along with registry data have underscored the enduring efficacy and continued safety of these drugs 72, 73.

Four different medications have been approved for use to treat hereditary angioedema attacks (Table 4). Plasma-derived C1-esterase inhibitor (C1-INH) concentrates (pdC1INH, Berinert) and recombinant human C1-INH (rhC1INH, Ruconest) are given by intravenous (IV) injection. The plasma kallikrein inhibitor (ecallantide) and the bradykinin B2 receptor antagonist (BDKRB2 antagonist) icatibant are administered subcutaneously. All 4 on-demand medications are very effective and generally safe. Ecallantide has been associated with allergic and even anaphylactic reactions in a relatively small number of cases (<2%) and therefore needs to be administered by a health care provider. These medications typically become effective within 60 minutes but have a relatively short half-life and cannot be used for prophylaxis (with the exception of plasma-derived C1-esterase inhibitor [Berinert] that has a longer half-life). Anabolic androgens and antifibrinolytic agents have no role in on-demand treatment.

Fresh frozen plasma (FFP) contains C1-esterase inhibitor (C1-INH) and can be used to treat hereditary angioedema attacks if none of the FDA-approved on-demand medications are available 74.The efficacy of fresh frozen plasma (FFP) has not been studied in randomized trials, and there are anecdotal reports of hereditary angioedema symptoms precipitously worsening after FFP administration possibly due to the fact that FFP contains factors that could lead to the generation of more bradykinin (HMWK, plasma prekallikrein, and FXII) in addition to C1-INH. If another acute therapy is not available, FFP remains an option as long as precautions are taken to protect the patient’s airway (particularly if oropharyngeal or laryngeal swelling is present). Solvent detergent–treated plasma may be safer than FFP due to reduced viral risk. In the absence of effective on-demand treatment, patients may require supportive care (ie, IV fluids, antiemetics, narcotic pain medication, or intubation). When effective on-demand treatment is not given, significantly higher morbidity is seen 75.

Although there have been no randomized controlled studies of on-demand treatment during attacks in patients with confirmed hereditary angioedema with normal C1 inhibitor (nC1-INH-hereditary angioedema), numerous open-label reports have revealed successful responses to each of the on-demand treatments used for hereditary angioedema with C1 inhibitor (C1-INH) deficiency 76.

Supportive care, including fluid replacement and pain management, should also be implemented.

Maintaining airway patency is the primary concern for patients with laryngeal edema. If the airway is threatened, the patient should be intubated by an experienced physician. In addition, the capability for emergency tracheostomy should be readily available. Because gastrointestinal edema usually involves severe pain, frequent vomiting, and the potential for hypotension, therapy should include aggressive fluid replacement and pain management.

Table 4. FDA-approved on-demand medications for hereditary angioedema attacks

| Drug (trade name, manufacturer) | Regulatory status | Self-administration | Dosage | Mechanism | Anticipated potential side effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ecallantide (Kalbitor, Dyax) | Approved in the United States for patients ≥12 y of age | No | 30 mg SC | Inhibits plasma kallikrein | Uncommon: antidrug antibodies, risk of anaphylaxis |

| Icatibant (Firazyr, Takeda) | Approved in the United States for patients ≥18 y of age; approved in Europe for patients ≥2 y of age | Yes | Pediatric (EU): 12-25 kg, 10 mg SC; 26-40 kg, 15 mg SC; 41-50 kg, 20 mg SC; 51-65 kg, 25 mg SC; >65 kg, 30 mg SC Adults: 30 mg SC | Bradykinin B2 receptor antagonist | Common: discomfort at injection site |

| Plasma-derived nanofiltered C1INH (Berinert, CSL Behring) | Approved in the United States and Europe for children and adults | Yes | 20 U/kg IV | Inhibits plasma kallikrein, coagulation factors Xlla, XIIf and Xla, C1s, C1r, MASP-1, MASP-2, and plasmin | Rare: risk of anaphylaxis Theoretical: transmission of infectious agent |

| Recombinant human C1-INH (Ruconest, Pharming) | Approved in the United States and Europe for adolescents and adults | Yes | 50 U/kg up to 4200 U IV | Inhibits plasma kallikrein, coagulation factors Xlla, XIIf and Xla, C1s, C1r, MASP-1, MASP-2, and plasmin | Uncommon: risk of anaphylaxis in rabbit-sensitized individuals Theoretical: transmission of infectious agent |

Abbreviations: C1INH = C1 inhibitor; FDA = Food and Drug Administration; HAE = hereditary angioedema; IV = intravenous; MASP-1, -2 = mannose-binding lectin–associated serine proteases 1, 2; SC = subcutaneous.

[Source 16 ]Short-term prophylaxis

Trauma and stress are well-known triggers of angioedema attacks 61. Short-term prophylactic therapy is imperative to prevent attacks of angioedema when the patient is at high risk of swelling, particularly before expected trauma such as surgery or dental procedures. Dental surgery, in particular, is associated with swelling of the oral cavity that can progress and cause airway obstruction. Novel targeted therapies such as a plasma-derived C1-esterase inhibitor, a kallikrein inhibitor (ecallantide), or a BDKRB2 antagonist (icatibant) should be given prior to the procedure if available 77. Short-term prophylaxis can be either a single dose of plasma-derived C1-esterase inhibitor or a course of anabolic androgen (danazol) 78.

A single dose of 20 IU/kg plasma-derived C1-esterase inhibitor can be given 1 to 12 hours before the stressor. Alternatively, anabolic androgens (ie, 400-600 mg/day of danazol) can be started 5 to 7 days before the stressor and continued for 2 to 5 days after the procedure. Recombinant human C1-esterase inhibitor (50 IU/kg) has also been used successfully for short-term prophylaxis 79, although there is less data and experience compared with plasma-derived C1-esterase inhibitor products. Fresh frozen plasma (FFP) can be used in the event that the treating physician cannot obtain plasma-derived C1-esterase inhibitor and there is insufficient time for a course of anabolic androgens.

There are no data on short-term prophylaxis for hereditary angioedema with normal C1 inhibitor (nC1-INH-hereditary angioedema). For patients with a confirmed diagnosis, the same approach as hereditary angioedema with C1 inhibitor (C1-INH) deficiency may be used with the important caveat that on-demand therapy be available if needed 16.

Table 5. FDA-approved prophylactic medications for hereditary angioedema

| Drug (trade name, manufacturer) | HAE regulatory status | Self-administration | Dosage | Mechanism | Anticipated potential side effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plasma-derived nanofiltered C1-INH (Cinryze, Takeda) | Approved in the United States and Europe for patients ≥6 years of age | Yes | Pediatric (6-11 years of age): 500 IU every 3-4 days IV Adolescents and adults: 1000 U IV every 3-4 days Doses up to 2500 U IV every 3-4 days may need to be considered based on individual patient response | Inhibits plasma kallikrein, coagulation factors Xlla, XIIf and Xla, C1s, C1r, MASP-1, MASP-2, and plasmin | Rare: risk of anaphylaxis Theoretical: transmission of infectious agent |

| Plasma-derived nanofiltered C1-INH (HAEGARDA, CSL Behring) | Approved in the United States for adolescents (≥12 years of age) and adults | Yes | 60 IU/kg SC twice-weekly | Inhibits plasma kallikrein, coagulation factors Xlla, XIIf and Xla, C1s, C1r, MASP-1, MASP-2, and plasmin | Rare: risk of anaphylaxis Theoretical: transmission of infectious agent |

| Lanadelumab (Takhzyro, Takeda) | Approved in the United States for adolescents and adults | Yes | 300 mg SQ every 2 weeks 300 mg every 4 weeks may be considered if a patient is well controlled (eg, attack free) for more than 6 months | Inhibits plasma kallikrein | Rare: risk of anaphylaxis Common: injection site reactions, upper respiratory tract infection and headach |

| Danazol (Danocrine, Sanofi-Synthelabo) | Approved in the United States for adults | Yes | Adult: 200 mg/d PO (100 mg every 3 day to 600 mg/day) Pediatric: 50 mg/day PO (50 mg/week to 200 mg/day) | Unknown | Common: weight gain, virilization, acne, altered libido, muscle pains and cramps, headaches, depression, fatigue, nausea, constipation, menstrual abnormalities, increase in liver enzymes, hypertension, and alterations in lipid profile Uncommon: decreased growth rate in children, masculinization of the female fetus, cholestatic jaundice, peliosis hepatis, and hepatocellular adenoma |

| Stanozolol (Winstrol, Winthrop) | Approved in the United States for adults and children | Yes | Adult: 2 mg/day PO (1 mg every 3 day to 6 mg/day) Pediatric: 0.5 mg/day PO (0.5 mg/week to 2 mg/day) | Same as danazol | |

| Oxandrolone | Not approved for HAE indication | Yes | Adult: 10 mg/day PO (2.5 mg every 3 day to 20 mg/day) Pediatric: 0.1 mg/kg/day PO (2.5 mg/week to 7.5 mg/day) | Unknown | Same as danazol |

| Methyltestosterone (Android) | Not approved for HAE indication | Yes | Adult men: 10 mg/day PO (5 mg every 3 days to 30 mg/day) Women and pediatric: not recommended | Unknown | Same as danazol |

| Epsilon aminocaproic acid (Amicar, Xanodyne Pharmaceuticals) | Not approved for HAE indication | Yes | Adult: 2 g PO tid (1 g bid to 4 g tid) Pediatric: 0.05 g/kg PO bid (0.025 g/kg bid to 0.1 g/kg bid) | Inhibits activation of plasminogen and activity of plasmin | Common: nausea, vertigo, diarrhea, postural hypotension, fatigue, muscle cramps with increased muscle enzymes Theoretical: thrombosis |

| Tranexamic acid (Cyklokapron, Pfizer; Lysteda, Ferring) | Not approved for HAE indication | Yes | Adult: 1 g PO bid (0.25 g bid to 1.5 g tid) Pediatric: 20 mg/kg PO bid (10 mg/kg bid to 25 mg/kg tid) | Inhibits activation of plasminogen and activity of plasmin | Same as epsilon aminocaproic acid |

Abbreviations: C1INH = C1 inhibitor; FDA = Food and Drug Administration; HAE = hereditary angioedema; PO = orally; bid = twice daily; tid = three times daily; IV = intravenous; SC = subcutaneous; SQ = subcutaneous.

[Source 16 ]Long-term prophylaxis

Some patients experience only infrequent and mild attacks and therefore require no long-term therapy. Clinicians generally recommend long-term therapy for patients who experience more than one attack per month, or who believe that the disease significantly interferes with their life style. The options include:

- An androgen (eg, danazol, stanozolol, methyltestosterone, or oxandrolone).

- An antifibrinolytic (tranexamic acid)

- A plasma-derived C1-esterase inhibitor (eg, nanofiltered C1-INH or plasma-derived C1-INH) 80

- A progestin (norethisterone).

The decision on when to use long-term prophylactic treatment cannot be made on rigid criteria but should be tailored to the needs of each hereditary angioedema patient 81. Decisions regarding which patients should be considered for long-term prophylactic treatment should take into account the patient’s quality of life and treatment preferences in the context of attack frequency, attack severity, comorbid conditions, and access to emergent treatment. Because disease severity may change over time, the need to start or continue long-term prophylaxis should be periodically reviewed and discussed with the patient.

Medications for long-term prophylactic treatment in hereditary angioedema with C1 inhibitor (C1-INH) deficiency can be divided into 2 broad categories: first-line or second-line. The first-line therapies include IV plasma-derived C1-esterase inhibitor replacement (Cinryze), subcutaneous (SC) plasma-derived C1-esterase inhibitor replacement (Haegarda), and a monoclonal inhibitor of plasma kallikrein (lanadelumab, Takhzyro). Second-line therapies include the anabolic androgens (ie, Danazol) and antifibrinolytics (tranexamic acid or epsilon aminocaproic acid). The United States Hereditary Angioedema Association Medical Advisory Board recommends the use of any of the first-line medications when long-term prophylaxis is indicated for patients with hereditary angioedema with C1 inhibitor (C1-INH) deficiency 16. Second-line prophylactic medications should be reserved for when first-line medications are not available or when the patient will only accept oral therapy, with acknowledgment of potential side effects. The potential availability of new first-line oral prophylactic medications in the future (see below) may also influence this choice. The long-term prophylaxis medicines are presented by first-line versus second-line and then in the order they were approved for hereditary angioedema.

First-line options

IV replacement therapy with plasma-derived C1-esterase inhibitor concentrate (Cinryze) has been shown to be both safe and effective for the prophylactic treatment of hereditary angioedema 70. IV plasma-derived C1-esterase inhibitor prophylaxis (Cinryze) was initially approved in 2008 for adolescents and adults based on an approximately 50% reduction in attack rate. After favorable outcomes of a second phase 3 study, indications were expanded in 2018 to include treatment of children as young as age 6 82.

Open-label extension data for IV plasma-derived C1-esterase inhibitor revealed improved outcomes with continued use. Efficacy of IV plasma-derived C1-esterase inhibitor prophylaxis directly correlated with the interval between dosing. Five subjects, all with risk factors for thromboembolic events, experienced serious adverse events of a thromboembolic nature but none were considered study drug related. Additional safety concerns such as infectious transmission, hypersensitivity reactions, and formation of anti-C1INH antibodies were not apparent during the study 83. Another 7.5% of subjects in the open-label extension cohort failed to improve. For patients who continue to have attacks despite receiving the standard dose of 1000 IU twice weekly, dose (up to 2500 IU) and frequency (3 times per week) escalation has been shown to improve efficacy 84.

Repeated IV administration can result in loss of readily available venous access unless great care is taken to preserve the veins. In some cases, indwelling ports have been placed to allow easier IV administration. Indwelling ports pose a significant risk of thrombosis and infection 85. Although a careful technique may reduce these risks, they cannot be eliminated. For these reasons, the US Hereditary Angioedema Association Medical Advisory Board discourages the use of indwelling ports unless deemed medically necessary, and further recommends that patients who require IV administration of drug exercise great care in protecting their veins by using butterfly needles with careful attention to technique, withdrawing the needle without pressure and then applying light pressure for 5 minutes after infusion without bending the elbow if an antecubital vein is used 16. Veins that are inflamed should not be used until the phlebitis is resolved. As outlined below, safe and effective alternative SC long-term prophylaxis treatments are now available, thus eliminating many of the problems associated with venous access for the future.

Subcutaneous plasma-derived C1-esterase inhibitor replacement

Subcutaneous plasma-derived C1-esterase inhibitor replacement (Haegarda) has recently been shown to be highly effective in preventing attacks of angioedema in patients with hereditary angioedema with C1 inhibitor (C1-INH) deficiency. The pivotal phase 3 trial demonstrated a statistically significant median reduction in attack rates of 95% at 60 IU/kg during the 16-week treatment period. There was a corresponding dramatic reduction in rescue medication use and a meaningful improvement in measures of health-related quality of life. Subcutaneous plasma-derived C1-esterase inhibitor replacement (Haegarda) appears safe and well tolerated with adverse events predominantly being transient local site reactions 86. In open-label extension studies, up to 83% of patients were free of attacks, and continuing improvements in health-related quality of life were seen 87.

Lanadelumab

Lanadelumab (Takhzyro), a fully human monoclonal antibody inhibitor of plasma kallikrein, was shown to be safe and effective for long-term prophylaxis in hereditary angioedema with C1 inhibitor (C1-INH) deficiency. The phase 3 study showed that lanadelumab at 150 mg every 4 weeks, 300 mg every 4 weeks, and 300 mg every 2 weeks significantly reduced attacks with the highest dose being most effective (86.9% reduction in attacks) 88. Use of on-demand treatment and incidence of high morbidity attacks were substantially reduced on lanadelumab. There were no significant safety concerns with the most common adverse events site reactions or dizziness. The FDA-recommended starting dose is 300 mg every 2 weeks. A dosing interval of 300 mg every 4 weeks may be considered after 6 months for well-controlled patients (attack free).

Second-line options

Although anabolic androgens (also known as 17α-alkylated androgens) such as danazol have been successfully used for prophylaxis for many years 89, they can cause significant dose-related side effects. The side effects of anabolic androgens are dose related, include virilization, weight gain, acne, hypertension, hepatotoxicity and atherosclerosis. All patients receiving anabolic androgens need to be carefully followed for the potential of drug-related side effects. Patients taking anabolic androgens should have their liver enzymes checked every six months. Since hepatic adenomas have been reported as a consequence of anabolic androgens liver and spleen ultrasonography should be done yearly. The lowest possible dose should be used to control hereditary angioedema to minimize side effects. The dose of anabolic androgens used to treat hereditary angioedema should be titrated down to find the lowest dose that prevents attacks. A reasonable starting dose for danazol is 100 to 200 mg/day.

Androgens are contraindicated in pregnancy, breastfeeding women, cancer, hepatitis, and childhood (under the age of 16) 90.

It is the position of the United States Hereditary Angioedema Association Medical Advisory Board that these drugs should not be used in patients who express a preference for an alternative therapy and that patients should not be required to fail anabolic androgen therapy as a prerequisite to receiving first-line long-term prophylaxis 16. Given the current therapeutic options for long-term prophylaxis in the United States, the United States Hereditary Angioedema Association Medical Advisory Board does not recommend the routine use of anabolic androgens for the treatment of hereditary angioedema 16.

Antifibrinolytics

Antifibrinolytic medications (tranexamic acid or epsilon aminocaproic acid) have been successfully used for long-term prophylaxis in hereditary angioedema with C1 inhibitor (C1-INH) deficiency 91, but are less effective than the other drugs described and are therefore seldom used for long-term prophylaxis of hereditary angioedema with C1 inhibitor deficiency in the United States.

Additional potential considerations

Although not yet FDA approved for long-term prophylaxis, recombinant human C1 inhibitor (Ruconest) demonstrated significant long-term prophylaxis efficacy in a phase II study 92. Given the periodic shortages that have impacted plasma-derived C1-INH product availability in the past, the use of recombinant human C1 inhibitor for prophylactic as well as on-demand treatment is an important consideration. In addition, the orally available once daily small molecule plasma kallikrein inhibitor berotralstat (BioCryst, Durham, NC) recently completed a pivotal phase III study in which it met its endpoints for long-term prophylaxis of hereditary angioedema with C1 inhibitor deficiency.

Long-term prophylaxis in patients with hereditary angioedema with normal C1 inhibitor

Long-term prophylaxis for patients with hereditary angioedema with normal C1 inhibitor (nC1-INH-hereditary angioedema) has not been studied in randomized placebo-controlled trials. Nevertheless, smaller open-label trials have suggested potential long-term prophylaxis strategies that can be used for hereditary angioedema with normal C1 inhibitor (nC1-INH-hereditary angioedema). The 2 major long-term prophylaxis modalities frequently used for hereditary angioedema with normal C1 inhibitor (nC1-INH-hereditary angioedema) are hormonal therapy and antifibrinolytics. long-term prophylaxis with C1 inhibitor concentrates has been occasionally used but should be approached with significant cautions as described below.

Hormonal therapy for long-term prophylaxis