Echinococcus hydatid cyst

Hydatid cysts result from infection by a tapeworm of either the Echinococcus granulosus or Echinococcus multilocularis and can result in cyst formation anywhere in the body. Hydatid disease also known as hydatidosis, is a zoonotic disease (a disease that is transmitted to humans from animals) caused by a parasitic infestation by a tapeworm of the genus Echinococcus 1. Human echinococcosis or hydatid disease is caused by the larval stages of cestodes (tapeworms) of the genus Echinococcus.

There are several identified species of Echinococcosis, four of which are of concern in humans 2:

- Echinococcus granulosus: infections cause cystic echinococcosis, also called hydatidosis. Human infection with Echinococcus granulosus leads to the development of one or more hydatid cysts located most often in the liver and lungs, and less frequently in the bones, kidneys, spleen, muscles and central nervous system.

- The asymptomatic incubation period of the disease can last many years until hydatid cysts grow to an extent that triggers clinical signs, however approximately half of all patients that receive medical treatment for infection do so within a few years of their initial infection with the parasite.

- Abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting are commonly seen when hydatids occur in the liver. If the lung is affected, clinical signs include chronic cough, chest pain and shortness of breath. Other signs depend on the location of the hydatid cysts and the pressure exerted on the surrounding tissues. Non-specific signs include anorexia, weight loss and weakness.

- Echinococcus multilocularis: infections cause alveloar echinocccosis.

- Alveolar echinococcosis is characterized by an asymptomatic incubation period of 5–15 years and the slow development of a primary tumour-like lesion which is usually located in the liver. Clinical signs include weight loss, abdominal pain, general malaise and signs of hepatic failure.

- Larval metastases may spread either to organs adjacent to the liver (for example, the spleen) or distant locations (such as the lungs, or the brain) following dissemination of the parasite via the blood and lymphatic system. If left untreated, alveolar echinococcosis is progressive and fatal.

- Echinococcus vogeli: infections cause polycystic echinococcosis.

- Echinococcus oligarthrus: infections cause polycystic echinococcosis.

The two most important forms, which are of medical and public health relevance in humans, are cystic echinococcosis and alveolar echinococcosis 3.

Echinococcus granulosus (sensu lato) causes cystic echinococcosis and is the form most frequently encountered 4. Another species, Echinococcus multilocularis, causes alveolar echinococcosis, and is becoming increasingly more common. Two exclusively New World species, Echinococcus vogeli and Echinococcus oligarthrus, are associated with “Neotropical echinococcosis”; Echinococcus vogeli causes a polycystic form whereas Echinococcus oligarthrus causes the extremely rare unicystic form.

Cystic echinococcosis (hydatid disease) is globally distributed and found in every continent except Antarctica. Hydatid disease (cystic echinococcosis) is not endemic in the United States, but the change in the immigration patterns and the marked increase in transcontinental transportation over the past 4 decades have caused a rise in the profile of this previously unusual disease throughout North America 5. Alveolar echinococcosis is confined to the northern hemisphere, in particular to regions of China, the Russian Federation and countries in continental Europe and North America.

In endemic regions, human incidence rates for cystic echinococcosis can reach more than 50 per 100 000 person-years, and prevalence levels as high as 5%–10% may occur in parts of Argentina, Peru, East Africa, Central Asia and China. In livestock, the prevalence of cystic echinococcosis found in slaughterhouses in hyperendemic areas of South America varies from 20%–95% of slaughtered animals.

The highest prevalence is found in rural areas where older animals are slaughtered. Depending on the infected species involved, livestock production losses attributable to cystic echinococcosis result from liver condemnation and may also involve reduction in carcass weight, decrease in hide value, decrease of milk production, and reduced fertility.

Many genotypes of Echinococcus granulosus have been identified that differ in their distribution, host range, and some morphological features; these are often grouped into separate species in modern literature. The known zoonotic genotypes within the Echinococcus granulosus sensu lato complex include the “classical” Echinococcus granulosus sensu stricto (G1–G3 genotypes), Echinococcus ortleppi (G5), and the Echinococcus canadensis group (usually considered G6, G7, G8, and G10). Research on the epidemiology and diversity of these genotypes is ongoing, and no consensus has been reached on appropriate nomenclature thus far.

Many people with echinococcosis or hydatid disease can be treated with anti-worm medicines.

A procedure that involves inserting a needle through the skin into the hydatid cyst may be tried. The contents of the cyst is removed (aspirated) through the needle. Then medicine is sent through the needle to kill the Echinococcus tapeworm. This treatment is not for hydatid cysts in the lungs.

Surgery is the treatment of choice for hydatid cysts that are large, infected, or located in organs, such as the heart and brain.

Hydatid disease key facts

- Human echinococcosis is a parasitic disease caused by tapeworms of the genus Echinococcus.

- The two most important forms of the disease in humans are cystic echinococcosis (hydatidosis) and alveolar echinococcosis.

- Humans are infected through ingestion of parasite eggs in contaminated food, water or soil, or after direct contact with animal hosts.

- Echinococcosis is often expensive and complicated to treat, and may require extensive surgery and/or prolonged drug therapy.

- Prevention programmes focus on deworming of dogs, which are the definitive hosts. In the case of cystic echinococcosis, control measures also include, slaughterhouse hygiene, and public education campaigns. Vaccination of lambs is also being used as an additional intervention.

- More than 1 million people are affected with echinococcosis at any one time.

Hydatid disease transmission

A number of herbivorous and omnivorous animals act as intermediate hosts of Echinococcus. They become infected by ingesting the parasite eggs in contaminated food and water, and the parasite then develops into larval stages in the viscera.

Carnivores act as definitive hosts for the parasite, and harbour the mature tapeworm in their intestine. The definitive hosts are infected through the consumption of viscera of intermediate hosts that contain the parasite larvae.

Humans act as so-called accidental intermediate hosts in the sense that they acquire infection in the same way as other intermediate hosts, but are not involved in transmitting the infection to the definitive host.

Several distinct genotypes of Echinococcus granulosus are recognised, some having distinct intermediate host preferences. Some genotypes are considered species distinct from Echinococcus granulosus. Not all genotypes cause infections in humans. The genotype causing the great majority of cystic echinococcosis infections in humans is principally maintained in a dog–sheep–dog cycle, yet several other domestic animals may also be involved, including goats, swine, cattle, camels and yaks.

Alveolar echinococcosis usually occurs in a wildlife cycle between foxes, other carnivores and small mammals (mostly rodents). Domesticated dogs and cats can also act as definitive hosts.

Hydatid cyst location

- Hepatic hydatid infection: most common organ, 76% of cases involve the liver 6

- Alveolar hydatid infection: second most common organ

- Splenic hydatid infection

- CNS hydatid infection

- Spinal hydatid infection

- Retroperitoneal hydatid infection

- Renal hydatid infection

- Musculoskeletal hydatid infection

Hydatid cyst classification

Based on morphology the hydatid cyst can be classified into four different types 7:

- Type I: simple cyst with no internal architecture

- Type II: cyst with daughter cyst(s) and matrix

- Type IIa: round daughter cysts at periphery

- Type IIb: larger, irregularly shaped daughter cysts occupying almost the entire volume of the mother cyst

- Type IIc: oval masses with scattered calcifications and occasional daughter cysts

- Type III: calcified cyst (dead cyst)

- Type IV: complicated cyst, e.g. ruptured cyst

World Health Organization (WHO) classification of hepatic hydatid cysts

The 2001 World Health Organization (WHO) classification of hepatic hydatid cysts is used to assess the stage of hepatic hydatid cyst on ultrasound and is useful in deciding the appropriate management for it depending on the stage of the cyst 8. This classification was proposed by the WHO in 2001 remains the most widely used classification for hepatic hydatid cysts.

World Health Organization hepatic hydatid cyst classification

- CL (cystic lesion)

- unilocular anechoic cystic lesion

- no any internal echoes or septations

- CE 1 (cystic echinococcosis stage 1) (active stage)

- CE 2 (cystic echinococcosis stage 2) (active stage): cyst with internal septation

- septa represent walls of daughter cyst(s) 9

- described as multivesicular, rosette, or honeycomb appearance

- CE 3 (cystic echinococcosis stage 3) (transitional stage): evolving appearance of daughter cyst(s) within the encompassing parent cyst

- 3A – daughter cysts have detached laminated membranes (water lily sign)

- 3B – daughter cysts within a solid matrix

- CE 4 (cystic echinococcosis stage 4) (inactive/degenerative)

- absence of daughter cysts

- mixed hypoechoic and hyperechoic matrix, resembling a ball of wool (ball of wool sign)

- CE 5 (cystic echinococcosis stage 5) (inactive/degenerative)

- arch-like, thick partially or completely calcified wall

Hydatid cyst disease causes

Humans become infected when they swallow the Echinococcus tapeworm eggs in contaminated food. The eggs then form cysts inside the body. A hydatid cyst is a closed pocket or pouch. The hydatid cysts keep growing, which leads to symptoms.

Echinococcus granulosus is an infection caused by tapeworms found in dogs, and livestock such as sheep, pigs, goats, and cattle. These tapeworms are around 2 to 7 mm long. The infection is called cystic echinococcosis. It leads to growth of cysts mainly in the lungs and liver. Hydatid cysts can also be found in the heart, bones, and brain.

Echinococcus multilocularis is the infection caused by tapeworms found in dogs, cats, rodents, and foxes. These tapeworms are around 1 to 4 mm long. The infection is called alveolar echinococcosis. It is a life-threatening condition because tumor-like growths form in the liver. Other organs, such as the lungs and brain can be affected.

Children or young adults are more prone to get the infection.

Echinococcus geographic distribution

Echinococcosis is common in:

- Africa

- Central Asia

- Southern South America

- The Mediterranean

- The Middle East

In rare cases, the infection is seen in the United States. It has been reported in California, Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah.

Echinococcus granulosus sensu lato occurs practically worldwide, and more frequently in rural, grazing areas where dogs ingest organs from infected animals. The geographic distribution of individual Echinococcus granulosus genotypes is variable and an area of ongoing research. The lack of accurate case reporting and genotyping currently prevents any precise mapping of the true epidemiologic picture. However, genotypes G1 and G3 (associated with sheep) are the most commonly reported at present and broadly distributed. In North America, Echinococcus granulosus is rarely reported in Canada and Alaska, and a few human cases have also been reported in Arizona and New Mexico in sheep-raising areas. In the United States, most infections are diagnosed in immigrants from counties where cystic echinococcosis is endemic. Some genotypes designated “Echinococcus canadensis” occur broadly across Eurasia, the Middle East, Africa, North and South America (G6, G7) while some others seem to have a northern holarctic distribution (G8, G10).

Echinococcus multilocularis occurs in the northern hemisphere, including central and northern Europe, Central Asia, northern Russia, northern Japan, north-central United States, northwestern Alaska, and northwestern Canada. In North America, Echinococcus multilocularis is found primarily in the north-central region as well as Alaska and Canada. Rare human cases have been reported in Alaska, the province of Manitoba, and Minnesota. Only a single autochthonous case in the United States (Minnesota) has been confirmed.

Echinococcus vogeli and Echinococcus oligarthrus occur in Central and South America.

Echinococcus hosts

Echinococcus granulosus definitive hosts are wild and domestic canids. Natural intermediate hosts depend on genotype. Intermediate hosts for zoonotic species/genotypes are usually ungulates, including sheep and goats (Echinococcus granulosus sensu stricto), cattle (“Echinococcus ortleppi”/G5), camels (“Echinococcus canadensis”/G6), and cervids (“Echinococcus canadensis”/G8, G10).

For Echinococcus multilocularis, foxes, particularly red foxes (Vulpes vulpes), are the primary definitive host species. Other canids including domestic dogs, wolves, and raccoon dogs (Nyctereutes procyonoides) are also competent definitive hosts. Many rodents can serve as intermediate hosts, but members of the subfamily Arvicolinae (voles, lemmings, and related rodents) are the most typical.

The natural definitive host of Echinococcus vogeli is the bush dog (Speothos venaticus), and possibly domestic dogs. Pacas (Cuniculus paca) and agoutis (Dasyprocta spp.) are known intermediate hosts. Echinococcus oligarthrus uses wild neotropical felids (e.g. ocelots, puma, jaguarundi) as definitive hosts, and a broader variety of rodents and lagomorphs as intermediate hosts.

Risk factors for hydatid disease include being exposed to:

- Cattle

- Deer

- Feces of dogs, foxes, wolves, or coyotes

- Pigs

- Sheep

- Camels

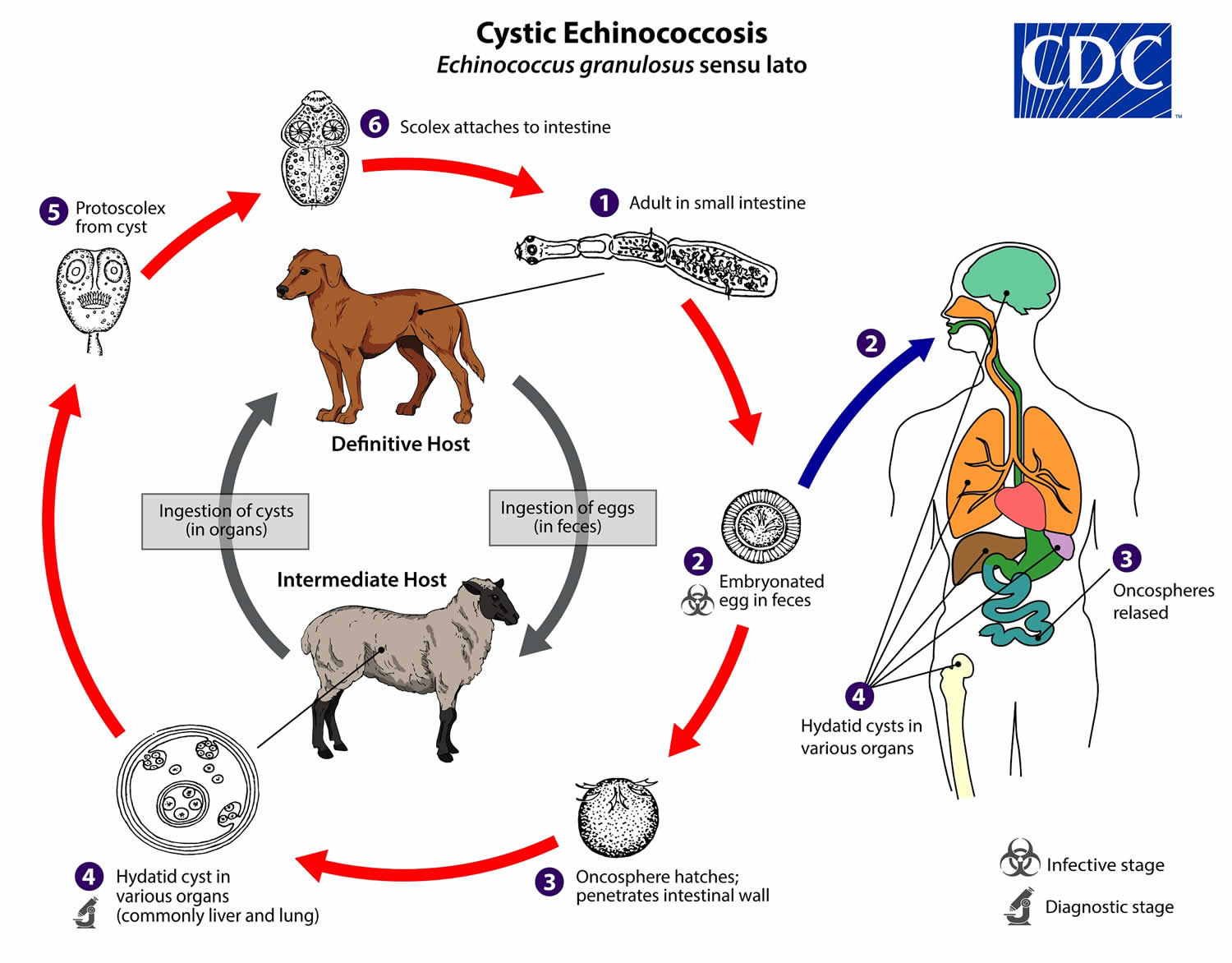

Echinococcus granulosus life cycle

The adult Echinococcus granulosus (sensu lato) (2—7 mm long) (number 1) resides in the small intestine of the definitive host. Gravid proglottids release eggs (number 2) that are passed in the feces, and are immediately infectious. After ingestion by a suitable intermediate host, eggs hatch in the small intestine and release six-hooked oncospheres (number 3) that penetrate the intestinal wall and migrate through the circulatory system into various organs, especially the liver and lungs. In these organs, the oncosphere develops into a thick-walled hydatid cyst (number 4) that enlarges gradually, producing protoscolices and daughter cysts that fill the cyst interior. The definitive host becomes infected by ingesting the cyst-containing organs of the infected intermediate host. After ingestion, the protoscolices (number 5) evaginate, attach to the intestinal mucosa (number 6), and develop into adult stages (number 1) in 32 to 80 days.

Humans are aberrant intermediate hosts, and become infected by ingesting eggs (number 2). Oncospheres are released in the intestine (number 3), and hydatid cysts develop in a variety of organs (number 4). If cysts rupture, the liberated protoscolices may create secondary cysts in other sites within the body (secondary echinococcosis).

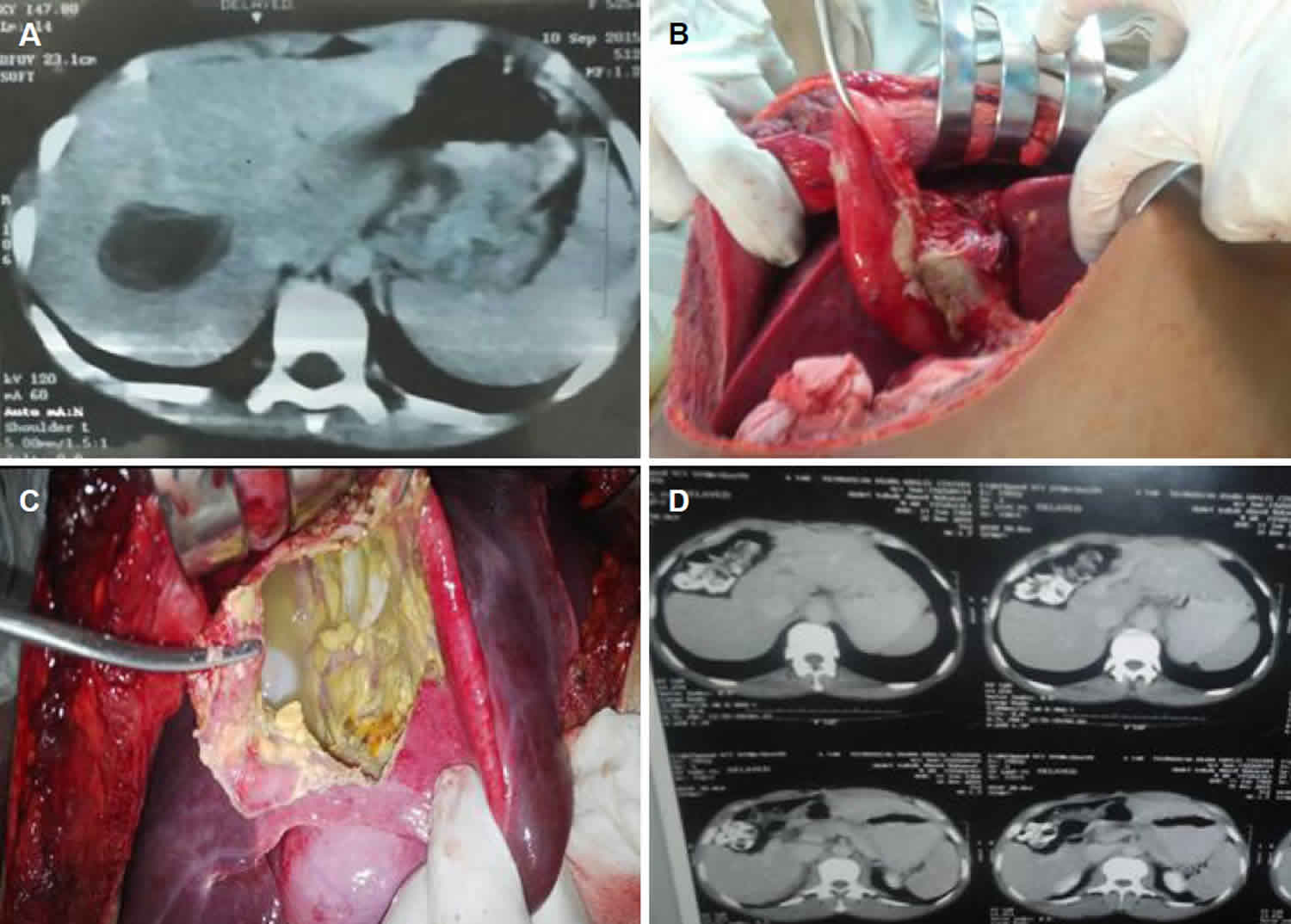

Figure 1. Echinococcus granulosus life cycle

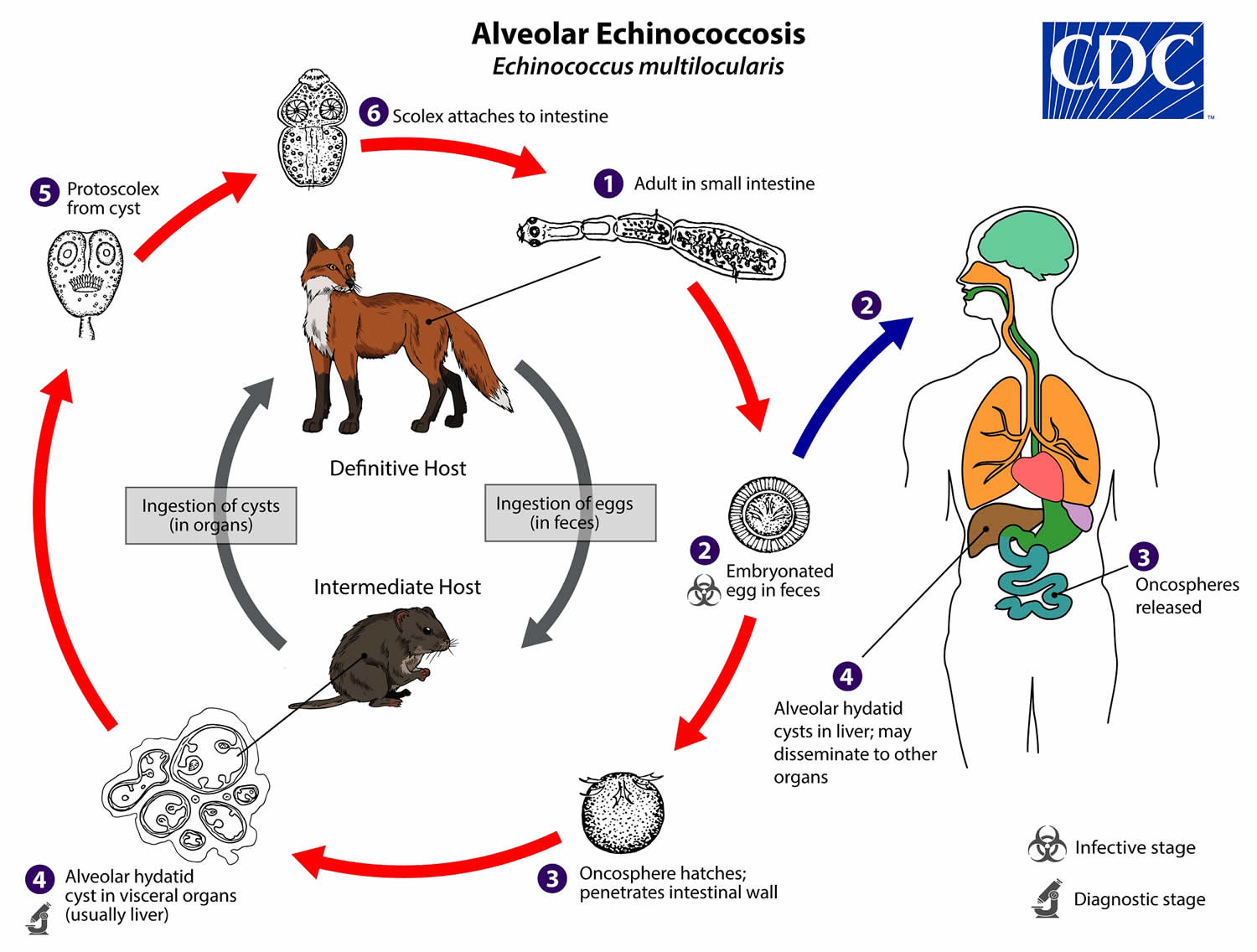

Alveolar echinococcosis life cycle

The adult Echinococcus multilocularis (1.2—4.5 mm long) (number 1) resides in the small intestine of the definitive host. Gravid proglottids release eggs (number 2) that are passed in the feces, and are immediately infectious. After ingestion by a suitable intermediate host, eggs hatch in the small intestine and releases a six-hooked oncosphere (number 3) that penetrates the intestinal wall and migrates through the circulatory system into various organs (primarily the liver for Echinococcus multilocularis). The oncosphere develops into a multi-chambered (“multilocular”), thin-walled (alveolar) hydatid cyst (number 4) that proliferates by successive outward budding. Numerous protoscolices develop within these cysts. The definitive host becomes infected by ingesting the cyst-containing organs of the infected intermediate host. After ingestion, the protoscolices (number 5) evaginate, attach to the intestinal mucosa (number 6), and develop into adult stages (number 1) in 32 to 80 days.

Humans are aberrant intermediate hosts, and become infected by ingesting eggs (number 2). Oncospheres (number 3) are released in the intestine and cysts develop within in the liver (number 4). Metastasis or dissemination to other organs (e.g., lungs, brain, heart, bone) may occur if protoscolices are released from cysts, sometimes called “secondary echinococcosis.”

Figure 2. Alveolar echinococcosis life cycle

Hydatid disease prevention

Measures to prevent cystic echinococcosis and alveolar hydatid disease (alveolar echinococcosis) include:

- Staying away from wild animals including foxes, wolves, and coyotes

- Avoiding contact with stray dogs

- Washing hands well after touching pet dogs or cats, and before handling food.

Cystic echinococcosis / hydatid disease

Surveillance for cystic echinococcosis in animals is difficult because the infection is asymptomatic in livestock and dogs. Surveillance is also not recognized or prioritized by communities or local veterinary services.

Cystic echinococcosis is a preventable disease as it involves domestic animal species as definitive and intermediate hosts. Periodic deworming of dogs with praziquantel (at least 4 times per year), improved hygiene in the slaughtering of livestock (including the proper destruction of infected offal), and public education campaigns have been found to lower and, in high-income countries, prevent transmission and alleviate the burden of human disease.

Vaccination of sheep with an Echinococcus granulosus recombinant antigen (EG95) offers encouraging prospects for prevention and control. The vaccine is currently being produced commercially and is registered in China and Argentina. Trials in Argentina demonstrated the added value of vaccinating sheep, and in China the vaccine is being used extensively.

A programme combining vaccination of lambs, deworming of dogs and culling of older sheep could lead to elimination of cystic echinococcosis disease in humans in less than 10 years.

Alveolar echinococcosis

Prevention and control of alveolar echinococcosisis more complex as the cycle involves wild animal species as both definitive and intermediate hosts. Regular deworming of domestic carnivores that have access to wild rodents should help to reduce the risk of infection in humans.

Deworming of wild and stray definitive hosts with anthelminthic baits resulted in significant reductions in alveolar echinococcosis prevalence in European and Japanese studies. Culling of foxes and unowned free-roaming dogs appears to be highly inefficient. The sustainability and cost–benefit effectiveness of such campaigns are controversial.

Hydatid disease symptoms

Hydatid cysts may produce no symptoms for 10 years or more.

Hydatid disease or Echinococcus granulosus infections often remain asymptomatic for years before the cysts grow large enough to cause symptoms in the affected organs. The rate at which symptoms appear typically depends on the location of the cyst. Hepatic and pulmonary signs/symptoms are the most common clinical manifestations, as these are the most common sites for cysts to develop In addition to the liver and lungs, other organs (spleen, kidneys, heart, bone, and central nervous system, including the brain and eyes) can also be involved, with resulting symptoms. Rupture of the cysts can produce a host reaction manifesting as fever, urticaria, eosinophilia, and potentially anaphylactic shock; rupture of the cyst may also lead to cyst dissemination.

Echinococcus multilocularis affects the liver as a slow growing, destructive tumor, often with abdominal pain and biliary obstruction being the only manifestations evident in early infection. This may be misdiagnosed as liver cancer. Rarely, metastatic lesions into the lungs, spleen, and brain occur. Untreated infections have a high fatality rate.

Echinococcus vogeli affects mainly the liver, where it acts as a slow growing tumor; secondary cystic development is common. Too few cases of E. oligarthrus have been reported for characterization of its clinical presentation.

As the hydatid disease advances and the hydatid cysts get larger, symptoms may include:

- Pain in the upper right part of the abdomen (liver cyst)

- Increase in size of the abdomen due to swelling (liver cyst)

- Bloody sputum (lung cyst)

- Chest pain (lung cyst)

- Cough (lung cyst)

- Severe allergic reaction (anaphylaxis) when cysts break open

Hydatid disease diagnosis

Your health care provider will perform a physical exam and ask you about your symptoms.

If your health care provider suspects cystic echinococcosis or alveolar hydatid disease (alveolar echinococcosis), tests that may be done to find the cysts include:

- X-ray, echocardiogram, CT scan, PET scan, or ultrasound to view the cysts

- Blood tests, such as enzyme-linked immunoassay (ELISA), liver function tests

- Fine needle aspiration biopsy

Most often, echinococcosis cysts are found when an imaging test is done for another reason.

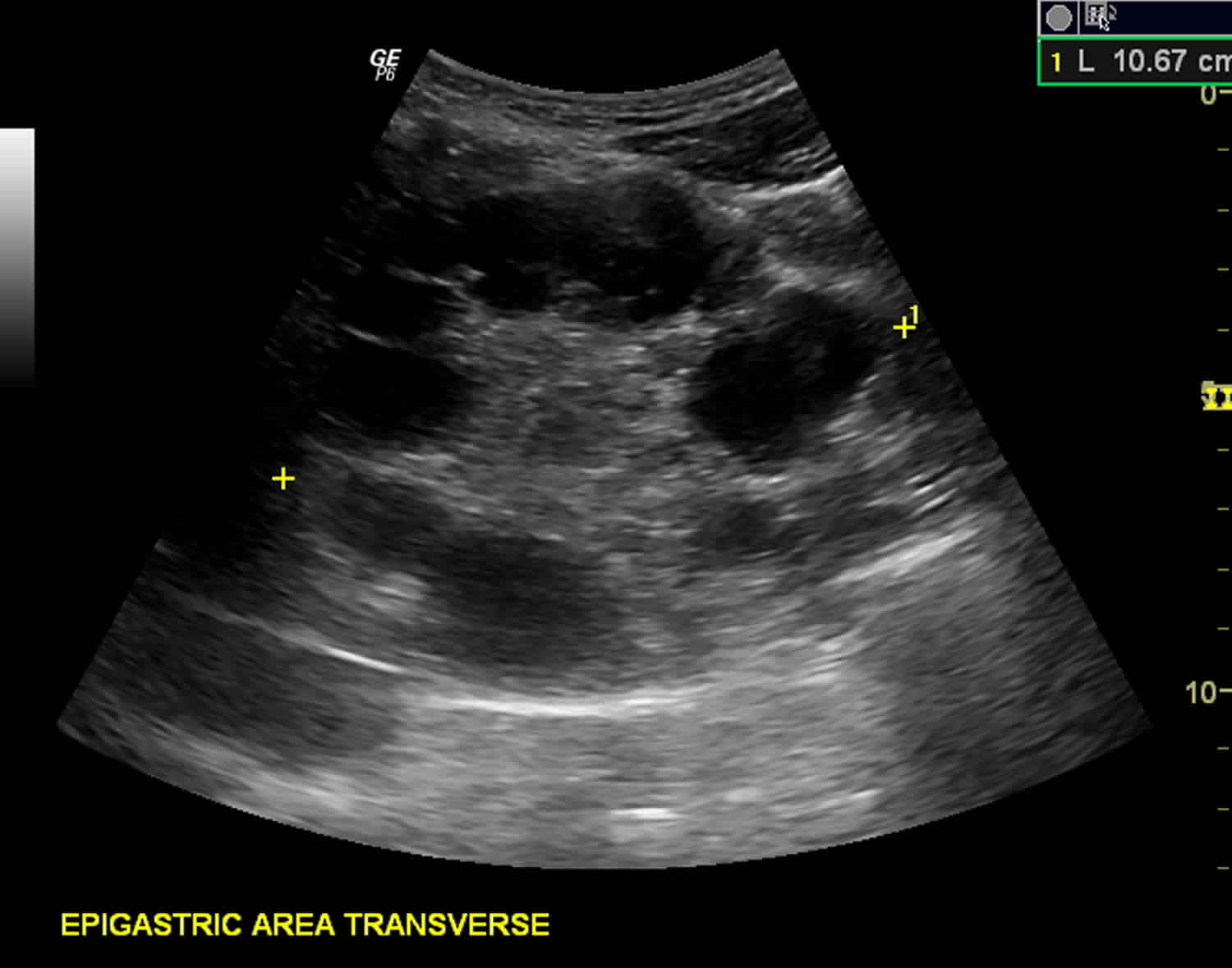

The diagnosis of echinococcosis relies mainly on findings by ultrasonography and/or other imaging techniques supported by positive serologic tests. Ultrasonography imaging is the technique of choice for the diagnosis of both cystic echinococcosis and alveolar echinococcosis in humans. This technique is usually complemented or validated by computed tomography (CT) and/or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans. In seronegative patients with hepatic image findings compatible with echinococcosis, ultrasound guided fine needle biopsy may be useful for confirmation of diagnosis. During such procedures precautions must be taken to control allergic reactions or prevent secondary recurrence in the event of leakage of hydatid fluid or protoscolices.

Figure 3. Hydatid cyst ultrasound

Footnote: Multiple hydatid cysts of variable sizes, sonographic appearance and stages seen in the liver, spleen, epigastric area (possibly retroperitoneal), pelvic cavity and anterior to the left psoas muscle (possibly retroperitoneal). Unilocular anechoic cyst (stage cystic lesion [CL]) according to WHO classification seen anterior to left psoas muscle at retroperitoneum. Unilocular mother cyst with honeycomb appearance (stage cystic echinococcosis [CE 2]) (according to WHO classification) seen in the pelvis, just cranially to the urinary bladder.

Antibody detection

Immunodiagnostic tests can be very helpful in the diagnosis of echinococcal disease, particularly in conjunction with imaging, and should be used before invasive methods. However, the clinician must have some knowledge of the characteristics of the available tests and the patient and parasite factors in order to interpret assay results. False-positive reactions may occur in persons with other cestode infections, some other helminth infections, cancer, and liver cirrhosis. Negative test results do not rule out echinococcosis because some cyst carriers do not have detectable antibodies. Whether the patient has detectable antibodies depends on the physical location, integrity, and vitality of the larval cyst.

Cystic echinococcal disease (Echinococcus granulosus)

Indirect hemagglutination (IHA), indirect fluorescent antibody (IFA) tests, and enzyme immunoassays (EIA) are sensitive tests for detecting antibodies in serum of patients with cystic disease; sensitivity rates vary from 60% to 90%, depending on the characteristics of the cases and antigens used. At present, the best available serologic diagnosis is obtained by using combinations of tests. EIA or IHA can be used for screening; positive reactions should be confirmed by immunoblot assay. As some tests may cross-react with sera from persons with cysticercosis, clinical and epidemiological information should also be used to support diagnosis. A commercial EIA kit is available in the United States.

Alveolar echinococcal disease (Echinococcus multilocularis)

Most patients with alveolar disease have detectable antibodies. Immunoaffinity-purified Echinococcus multilocularis antigens (Em2) used in EIA allow the detection of positive antibody reactions in more than 95% of alveolar cases. Comparing serologic reactivity to Em2 antigen with that to antigens containing components of both Echinococcus multilocularis and Echinococcus granulosus permits discrimination of patients with alveolar from those with cystic disease. Combining two purified Echinococcus multilocularis antigens (Em2 and recombinant antigen II/3-10) in a single immunoassay improves sensitivity and specificity. These antigens are included in commercial EIA kit in Europe, but are not available in the United States. Em2 tests are more useful for postoperative follow-up than for monitoring the effectiveness of chemotherapy. Em18-ELISA is considered suitable for monitoring treatment efficacy in AE patients.

Polycystic echinococcosis (Echinococcus vogeli)

The serologic diagnosis of polycystic echinococcosis has not been extensively studied as infections with Echinococcus vogeli are very rare. One antigen has been described (Ev2) that distinguishes Echinococcus vogeli from Echinococcus granulosus but not Echinococcus multilocularis.

Hydatid cyst treatment

Both cystic echinococcosis and alveolar echinococcosis are often expensive and complicated to treat, sometimes requiring extensive surgery and/or prolonged drug therapy; the choice depends on a variety of factors including the patient’s clinical picture and the size of the cyst (ultrasound-guided staging system is the method used in liver cysts).

There are 4 options for the treatment of cystic echinococcosis:

- Percutaneous treatment of the hydatid cysts with the PAIR (Puncture, Aspiration, Injection, Re-aspiration) technique;

- Surgery

- Anti-infective drug treatment

- “Watch and wait”.

The choice must primarily be based on the ultrasound images of the cyst, following a stage-specific approach, and also on the medical infrastructure and human resources available.

In cystic echinococcosis, surgery remains the primary treatment and the only hope for complete cure. Better forms of chemotherapy and newer methods, such as the puncture, aspiration, injection, and reaspiration (PAIR) technique are now available but need to be tested. Currently, indications for these modes of therapy are restricted. In cystic echinococcosis, one should consider the risks and benefits, indications, and contraindications for each case before making a decision regarding the type and timing of surgery.

For alveolar echinococcosis, early diagnosis and radical (tumor-like) surgery followed by anti-infective prophylaxis with albendazole remain the key elements. If the lesion is confined, radical surgery can be curative. Unfortunately in many patients the disease is diagnosed at an advanced stage. As a result, if palliative surgery is carried out without complete and effective anti-infective treatment, frequent relapses will occur.

A retrospective study 10 showed laparoscopic therapy and puncture, aspiration, injection, and reaspiration (PAIR) intervention to be safe and effective alternative options to open surgery in patients with a suitable indication such as cyst type and location.

Chemotherapy in cystic echinococcosis

Indications:

Chemotherapy is indicated in patients with primary liver or lung cysts that are inoperable (because of location or medical condition), patients with cysts in 2 or more organs, and peritoneal cysts.

Contraindications:

Early pregnancy, bone marrow suppression, chronic hepatic disease, large cysts with the risk of rupture, and inactive or calcified cysts are contraindications. A relative contraindication is bone cysts because of the significantly decreased response.

Chemotherapeutic agents:

Two benzimidazoles are used, albendazole and mebendazole. Albendazole is administered in several 1-month oral doses (10-15 mg/kg/d) separated by 14-day intervals. New data for continuous treatment are emerging from China. The optimal period of treatment ranges from 3-6 months, with no further increase in the incidence of adverse effects if this period is prolonged. Mebendazole is also administered for 3-6 months orally in dosages of 40-50 mg/kg/d. Limited data are available on the weekly use of praziquantel, an isoquinoline derivative, at a dose of 40 mg/kg/wk, especially in cases in which intraoperative spillage has occurred. Albendazole has been found ineffective in the treatment of primary liver cysts in patients who are surgical candidates 11.

Monitoring:

Monitor patients for adverse effects of agents every 2 weeks with a complete blood cell (CBC) count and liver enzyme evaluation for the first 3 months and then every 4 weeks. Monitoring albendazole and mebendazole serum levels is desirable, but few laboratories are capable of performing this measurement. Imaging studies are required for follow-up on the morphologic status of the cyst.

Outcome from medical treatment of cystic echinococcosis:

Response rates in 1000 treated patients showed that 30% had cyst disappearance (cure), 30%-50% had a decrease in the size of the cyst (improvement), and 20%-40% had no changes. Also, younger adults responded better than older adults.

PAIR in cystic echinococcosis

The PAIR (Puncture, Aspiration, Injection, Re-aspiration) technique is performed using either ultrasound or computed tomography (CT) guidance, involves aspiration of the cyst contents via a special cannula, followed by injection of a scolicidal agent for at least 15 minutes, and then reaspiration of the cystic contents. This is repeated until the return is clear. The cyst is then filled with isotonic sodium chloride solution. Perioperative treatment with a benzimidazole is mandatory (4 d prior to the procedure and for 1-3 mo after).

The PAIR technique can be performed on liver, bone, and kidney cysts but should not be performed on lung and brain cysts. The cysts should be larger than 5 cm in diameter and type I or II according to the Gharbi ultrasound classification of liver cysts (ie, type I is purely cystic; type II is purely cystic plus hydatid sand; type III has the membrane undulating in the cystic cavity; and type IV has peripheral or diffuse distribution of coarse echoes in a complex and heterogeneous mass). PAIR (Puncture, Aspiration, Injection, Re-aspiration) technique can be performed on type III cysts as long as it is not a honeycomb cyst.

Indications:

Inoperable patients; patients refusing surgery; patients with multiple cysts in segment I, II, and III of the liver; and relapse after surgery or chemotherapy are indications for the PAIR technique.

Contraindications:

Early pregnancy, lung and brain cysts, inaccessible cysts, superficially located cysts (risk of spillage), type II honeycomb cysts, type IV cysts, and cysts communicating with the biliary tree (risk of sclerosing cholangitis from the scolecoidal agent) are contraindications for the PAIR technique.

Outcome:

The reduced cost and shorter hospital stay associated with PAIR compared to surgery make it desirable. The risk of spillage and anaphylaxis is considerable, especially in superficially located cysts, and transhepatic puncture is recommended. Sclerosing cholangitis (chemical) and biliary fistulas are other risks. Experience is still limited, but early reports are supportive of this technique if the indications are followed.

Chemotherapy in alveolar hydatid disease

Indications:

Chemotherapy with benzimidazoles is used perioperatively for approximately 2 years in patients in whom radical resection is feasible because of possible undetected residual parasite tissue. In patients who undergo a partial resection, patients who are inoperable, or patients who have had a liver transplant, long-term chemotherapy is required (3-10 years).

Contraindications:

Because chemotherapy is the only treatment in certain cases, contraindications are limited to early pregnancy and severe leukopenia. Chemotherapeutic agents and patient monitoring are the same as with cystic echinococcosis, but the length of treatment is different.

Outcome:

A significant increase in 10-year survival rates exists in patients receiving chemotherapy compared to patients who are not treated (85%-90% vs 10%, respectively).

Interventional procedures in alveolar hydatid disease

Patients with alveolar hydatid disease require interventional procedures when radical complete resective surgery is not possible. Local complications may occur. These interfere with the function of the organ and may be alleviated by certain interventional procedures. These procedures can be performed endoscopically or under ultrasound or CT guidance. Dilatation, stenting, drainage of collections, and sclerosis of esophageal varices are some examples.

Indications:

These include hyperbilirubinemia, vena cava thrombosis, portal vein thrombosis, necrotic collections, and bleeding esophageal varices.

Contraindications:

Postinterventional chemotherapy is not possible, and the risk of spreading the parasite is high.

Surgical care

The indications and type of surgery are different for cystic echinococcosis (cystic echinococcosis) and alveolar echinococcosis (alveolar hydatid disease).

Cystic echinococcosis

Indications:

Large liver cysts with multiple daughter cysts; superficially located single liver cysts that may rupture (traumatically or spontaneously); liver cysts with biliary tree communication or pressure effects on vital organs or structures; infected cysts; and cysts in lungs, brain, kidneys, eyes, bones, and all other organs are indications for surgery.

Contraindications:

General contraindications to surgical procedures (eg, extremes of age, pregnancy, severe preexisting medical conditions); multiple cysts in multiple organs; cysts that are difficult to access; dead cysts; calcified cysts; and very small cysts are contraindications.

Choice of surgical technique:

Radical surgery (total pericystectomy or partial affected organ resection, if possible), conservative surgery (open cystectomy), or simple tube drainage of infected and communicating cysts for surgical options. The more radical the procedure, the lower the risk of relapses but the higher the risk of complications. Patient care must be individualized accordingly.

Laparoscopic approach has gained more acceptance and popularity in recent years.

Description of surgical procedure

The basic steps of the procedure are eradication of the parasite by mechanical removal, sterilization of the cyst cavity by injection of a scolicidal agent, and protection of the surrounding tissues and cavities.

Scolicidal agents include formalin, hydrogen peroxide, hypertonic saline, chlorhexidine, absolute alcohol, and cetrimide. A variety of complications have been described with all scolicidal agents, but in the authors’ experience, 0.5% cetrimide solution provides the best protection with the least complications. Other scolicidal agents are 70%-95% ethanol and 15%-20% hypertonic saline solutions. A report by Ochieng’-Mitula and Burt in 1996 on the injection of ivermectin in the hydatid cysts of infected gerbils revealed several damaged cysts with no viable protoscoleces. [10] Further evaluation of this scolicidal agent is needed.

At surgery, the exact location of the cyst is identified and correlated with the radiologic findings. The surrounding tissues are protected by covering them with cetrimide-soaked pads. The cyst is then evacuated using a strong suction device, and cetrimide is injected into the cavity. This procedure is repeated until the return is completely clear. Cetrimide is instilled and allowed to sit for 10 minutes, after which it is evacuated, and the cavity is irrigated with isotonic sodium chloride solution. This ensures both mechanical and chemical evacuation and destruction of all cyst contents. During this process, care is taken to ensure no spillage occurs to prevent seeding and secondary infestation.

The cavity is then filled with isotonic sodium chloride solution and closed. Rarely, the omentum is needed to fill the cavity. The cyst fluid is inspected for bile staining at the end of the evacuation and irrigation process. The inside of the cyst is inspected, and any bile duct communication is sutured. In case of infected cysts with biliary communication, closed suction drainage is required. Regardless of whether an open or a laparoscopic approach is chosen, these basic principles must be followed in order to ensure the safety of the procedure.

Medical requirements

The medical staff at the treating center should have experience with treating cystic echinococcosis. Concomitant treatment with benzimidazoles (albendazole or mebendazole) has been reported to reduce the risk of secondary echinococcosis. Treatment is started 4 days preoperatively and lasts for 1 month.

Alveolar echinococcosis

Indications:

The indication is resectability of the liver lesion (assessed by imaging techniques preoperatively).

Contraindications:

These are inoperable lesions, extensive lesions, and lesions extending outside the liver and involving other organs.

Choice of surgical technique:

Radical surgery with complete excision of the lesion is the only chance for cure. In certain cases, total hepatectomy with transplantation has been performed as long as no extra hepatic disease is present. Reemergence of the parasite in the transplanted liver and distant metastasis occur under immunosuppression. Partial resections of unresectable masses are considered to decrease the parasite load to aid the chemotherapeutic agents 12. More recently, ex vivo liver resection combined with autotransplantation appears to show potential for curing end-stage hepatic alveolar echininococcosis in those with unresectable lesions 13.

Medical requirements:

Surgical staff experienced in major liver resections and medical staff experienced in the administration of chemotherapy to persons with alveolar hydatid disease are required. Perform liver transplantations in centers where a well-coordinated and experienced team is available.

Long-term monitoring

Outpatient care is directed towards the following end points:

- Chemotherapy: Postoperative treatment with benzimidazoles is continued for 1 month in patients with cystic echinococcosis who have successfully undergone complete resection or puncture, aspiration, injection, and reaspiration (PAIR). The treatment is continued for 3-6 months for patients with resected alveolar echinococcosis, incompletely resected cystic echinococcosis, spillage during surgery or PAIR, and metastatic lesions. Chemotherapy is needed for 3-10 years for patients with partially resected alveolar echinococcosis, unresectable alveolar echinococcosis, or liver transplant for alveolar echinococcosis.

- Laboratory tests: Patients on benzimidazoles should have a complete blood cell (CBC) count and liver enzyme evaluation performed at biweekly intervals for 3 months and then every 4 weeks to monitor for toxicity. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) or indirect hemagglutination tests are usually performed at 3-, 6-, 12-, and 24-month intervals to assess for recurrence of resected disease or aggravation of an existing disease.

- Imaging: Ultrasonography and/or computed tomography (CT) scanning are used in follow-up at the same intervals as the laboratory tests or as clinically indicated.

Hydatid disease prognosis

Prognosis mainly depends on the type of infestation (ie, whether it is cystic echinococcosis or alveolar echinococcosis). In cystic echinococcosis, the prognosis is generally good, and complete cure is possible with total surgical excision without spillage. Spillage occurs in 2%-25% of cases (depends on the location and surgeon’s experience), and the operative mortality rate varies from 0.5%-4% for the same reasons.

In alveolar echinococcosis, the prognosis is much worse. Cure is only possible with early detection and complete surgical excision. In patients in whom the latter is not possible, the addition of long-term chemotherapy has decreased the 10-year mortality rates from 94% to 10%.

Morbidity and mortality

Morbidity is usually secondary to free rupture of the echinococcal cyst (with or without anaphylaxis), infection of the cyst, or dysfunction of affected organs. Examples of dysfunction of affected organs are biliary obstruction, cirrhosis, bronchial obstruction, renal outflow obstruction, increased intracranial pressure secondary to a mass, and hydrocephalus secondary to cerebrospinal fluid outflow obstruction.

In cystic echinococcosis, mortality is secondary to anaphylaxis, systemic complications of the cysts (eg, sepsis, cirrhosis, respiratory failure), or operative complications.

In clinical cases of alveolar echinococcosis, the mortality rate is 50%-60%. This figure reaches 100% for untreated or poorly treated alveolar echinococcosis. Sudden death has been reported with alveolar echinococcosis in asymptomatic patients (autopsy diagnosis).

- Ravis E, Theron A, Lecomte B, Gariboldi V. Pulmonary cyst embolism: a rare complication of hydatidosis. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2018 Jan 1. 53(1):286-7.[↩]

- Almulhim AM, John S. Echinococcus Granulosus (Hydatid Cysts, Echinococcosis) [Updated 2019 May 4]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2019 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK539751[↩]

- Echinococcosis. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/echinococcosis[↩]

- Echinococcosis. https://www.cdc.gov/dpdx/echinococcosis/[↩]

- Hydatid Cysts. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/178648-overview[↩]

- Hydatid Disease: Radiologic and Pathologic Features and Complications. Iván Pedrosa, Antonio Saíz, Juan Arrazola, Joaquín Ferreirós, and César S. Pedrosa. RadioGraphics 2000 20:3, 795-817 https://doi.org/10.1148/radiographics.20.3.g00ma06795[↩]

- Hydatid Disease from Head to Toe. Pinar Polat, Mecit Kantarci, Fatih Alper, Selami Suma, Melike Bedel Koruyucu, and Adnan Okur. RadioGraphics 2003 23:2, 475-494 https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.232025704[↩]

- Brunetti E, Kern P, Vuitton DA. Writing Panel for the WHO-IWGE. Expert consensus for the diagnosis and treatment of cystic and alveolar echinococcosis in humans. Acta Trop. 2010;114:1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2009.11.00[↩]

- Pakala T, Molina M, Wu GY. Hepatic Echinococcal Cysts: A Review. J Clin Transl Hepatol. 2016;4(1):39–46. doi:10.14218/JCTH.2015.00036 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4807142[↩][↩][↩]

- Chen X, Cen C, Xie H, Zhou L, Wen H, Zheng S. The comparison of 2 new promising weapons for the treatment of hydatid cyst disease: PAIR and laparoscopic therapy. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2015 Aug. 25(4):358-62.[↩]

- Kapan S, Turhan AN, Kalayci MU, Alis H, Aygun E. Albendazole is not effective for primary treatment of hepatic hydatid cysts. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008 May. 12(5):867-71.[↩]

- Mamarajabov S, Kodera Y, Karimov S, et al. Surgical alternatives for hepatic hydatid disease. Hepatogastroenterology. 2011 Nov-Dec. 58(112):1859-61.[↩]

- Yang X, Qiu Y, Huang B, et al. Novel techniques and preliminary results of ex vivo liver resection and autotransplantation for end-stage hepatic alveolar echinococcosis: A study of 31 cases. Am J Transplant. 2018 Jul. 18(7):1668-79.[↩]