Low back pain

Low back pain also called lower back pain, refers to pain felt in the lower part of the spine (the lumbar spine). Low back pain is a very common problem with more than 30% of U.S. adults report experiencing low back pain in the preceding three months 1 and is the fifth most common reason people go to the doctor or miss work, and it is a leading cause of disability worldwide 2. A systematic review estimated that the annual cost of low back pain in the United States is more than $600 billion, with most of this cost attributed to work loss 3. Among people with back pain who seek care, the most improvement in pain occurs in the first three months after diagnosis, with little improvement thereafter. Regardless, one study that followed individuals with low back pain for two years showed that 70% of these patients never took sick leave. Rates of sick leave were somewhat higher in blue-collar workers than white-collar workers 4.

Low back pain definitions 5

- Acute low back pain: Back pain duration < 6 weeks. Most low back pain is acute. It tends to resolve on its own within a few days with self-care and there is no residual loss of function. In some cases a few months are required for the symptoms to disappear.

- Subacute low back pain: Back pain duration ≥ 6 weeks but < 12 weeks (3 months).

- Chronic low back pain: Back pain disabling the patient from some life activity for ≥ 12 weeks (3 months) or longer. About 20 percent of people affected by acute low back pain develop chronic low back pain with persistent symptoms at one year. Even if pain persists, it does not always mean there is a medically serious underlying cause or one that can be easily identified and treated. In some cases, treatment successfully relieves chronic low back pain, but in other cases pain continues despite medical and surgical treatment.

- Recurrent low back pain: Acute low back pain in a patient who has had previous episodes of low back pain from a similar location, with asymptomatic intervals between episodes 6.

Up to 70% of people will suffer at least one episode of back pain at some point in their lives, and this will usually resolve spontaneously with some over-the-counter pain relief 7. However, when your low back pain is persistent, severe or starts to impact on living it becomes necessary to seek medical attention. Seek immediate care if your back pain:

- Causes new bowel or bladder problems

- Is accompanied by a fever

- Follows a fall, blow to your back or other injury.

Guidelines from the American College of Physicians and the American Pain Society recommend initial categorization of low back pain into 8:

- Nonspecific low back pain. Low back pain is categorized as nonspecific low back pain without radiculopathy, low back pain with radicular symptoms, or secondary low back pain with a spinal cause.

- Low back pain with potential radicular symptoms,

- Secondary low back pain associated with a specific spinal cause (i.e., neoplasm or infectious process).

There are a number of causes of lower back pain but in the majority of sufferers no cause is found. Injuries are a common cause of low back pain. Examples include a muscle strain or spasm, ligament sprain, joint problem, or a “slipped disk.” A slipped disk, or herniated disk, has to do with your spine. It occurs when a disk between the bones of your spine swells or bulges and presses on your nerves. Twisting while lifting often causes this. Many people who have a slipped disk do not know what caused it.

You may have low back pain after doing an activity you aren’t used to, such as lifting heavy furniture or doing yard work. Sudden events, such as a fall or a car wreck, can cause low back pain. You also may have low back pain from an injury to another part of your body.

Conditions commonly linked to lower back pain include:

- Muscle or ligament strain. Repeated heavy lifting or a sudden awkward movement can strain back muscles and spinal ligaments. If you’re in poor physical condition, constant strain on your back can cause painful muscle spasms.

- Sacroiliac joint pain. Located where your lower spine and pelvis connect, inflammation or wear over time can cause pain in the buttocks or back of the thigh.

- Bulging or ruptured disks. Disks act as cushions between the bones (vertebrae) in your spine. The soft material inside a disk can bulge or rupture and press on a nerve causing leg pain or back pain. However, you can have a bulging or ruptured disk without back pain. Disk disease is often found incidentally when you have spine X-rays for some other reason.

- Spine arthritis. Due to aging, genetics and wear over time, the joints of the spine may develop arthritis and cause pain and stiffness. Osteoarthritis can affect the lower back. In some cases, arthritis in the spine can lead to a narrowing of the space around the spinal cord, a condition called spinal stenosis (lumbar spinal stenosis). Other forms of arthritis, like rheumatoid arthritis, can also affect the spine. Ankylosing Spondylitis can cause low back pain but more commonly causes stiffness.

- Osteoporosis. Your spine’s vertebrae can develop painful fractures if your bones become porous and brittle.

- Skeletal irregularity. Abnormal curves, defects or abnormal bone sizes in the spine can result in back pain.

- Infection and tumor. Certain infections and tumors that affect the vertebra or spinal canal can cause back pain.

- Referred pain – organs in the pelvis and lower abdomen can sometimes cause a sensation of pain in the back.

- Fractures and trauma. Crush fractures

Some patients, present with low back pain as the initial manifestation of a more serious pathology, such as cancer (malignancy), spinal fracture, infection, or cauda equina syndrome 9. Spinal fracture and cancer (malignancy) are the most common serious pathologies affecting the spine 9. In patients with low back pain presenting to primary care, between 1% and 4% will have a spinal fracture 10 and in less than 1% malignancy, whether primary tumor or metastasis, will be the underlying cause 11.

Commonly suggested “red flags” for malignancy in clinical practice guidelines are 12:

- Age > 50 years,

- No improvement in symptoms after one month,

- Insidious onset,

- A previous history of cancer,

- No relief with bed rest,

- Unexplained weight loss,

- Fever,

- Thoracic pain or being systematically unwell.

These “red flags” are usually elicited through the initial assessment (history taking and physical examination), to decide which patients should be referred for imaging or specialist consultation. The limited evidence available suggests that only one “red flag” when used in isolation, a previous history of cancer, meaningfully increases the likelihood of cancer 11. “Red flags” such as insidious onset, age > 50, and failure to improve after one month have high false positive rates suggesting that uncritical use of these “red flags” as a trigger to order further investigations will lead to unnecessary investigations that are themselves harmful, through unnecessary radiation and the consequences of these investigations themselves producing false‐positive results 11. While the lack of evidence to support or refute the use of “red flags” is recognized, a more pragmatic solution is to consider the possibility of spinal malignancy (in light of its low prevalence in primary care) when a combination of recommended “red flags” are found to be positive.

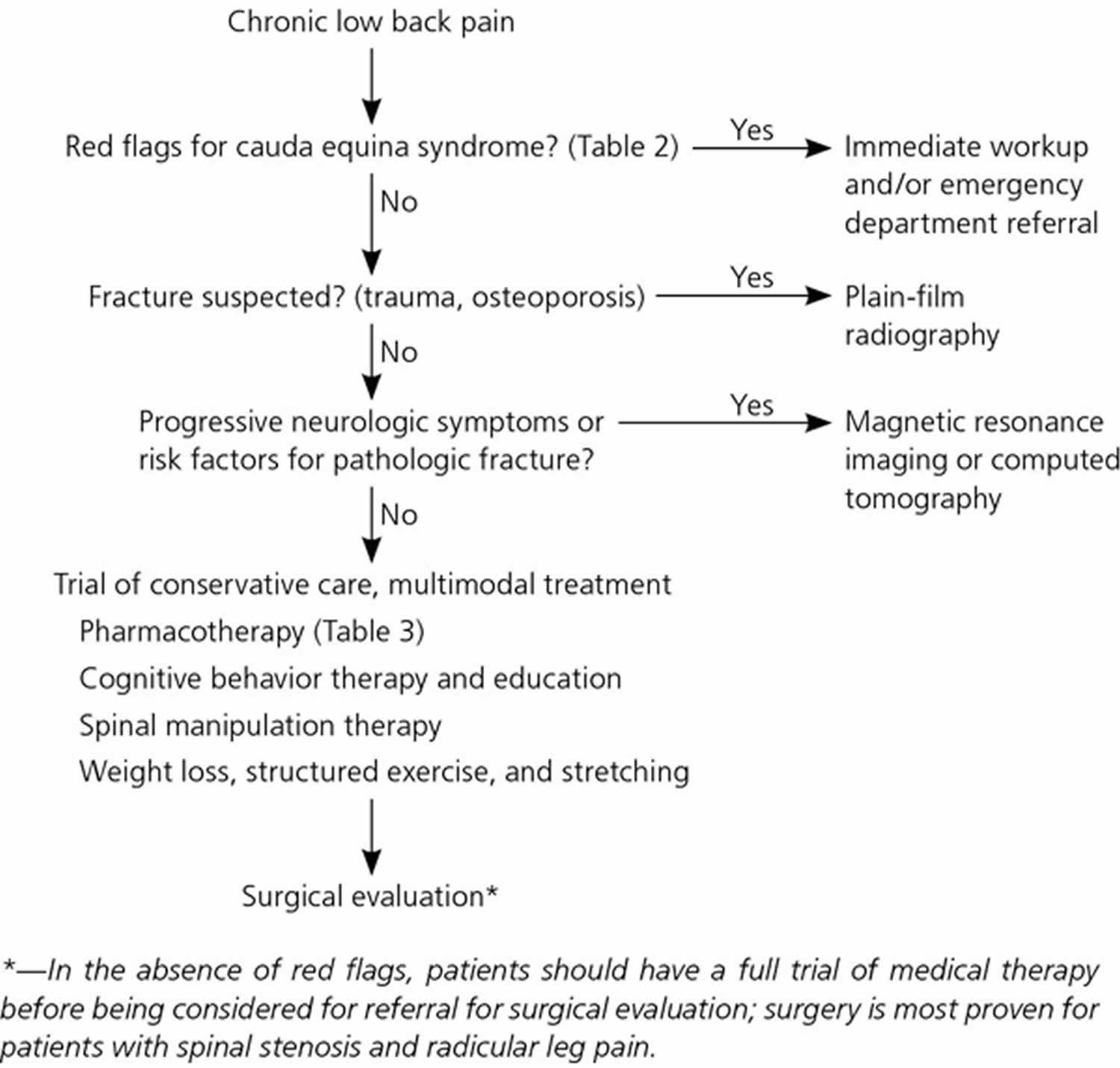

In the absence of red flags, plain-film radiography, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), or computed tomography (CT) is not warranted in the acute presentation of low back pain and does not modify patient outcomes 13. The American College of Physicians/American Pain Society joint guidelines discourage routine imaging for nonspecific low back pain 8. Consideration of imaging should be guided by the history and physical examination. Unless a high suspicion for infection, fracture, or cauda equina syndrome exists, clinicians should not order imaging for acute low back pain. Numerous high-quality randomized studies have compared immediate vs. delayed imaging with no appreciable differences in disease course 14, 13. Additionally, no difference in outcomes for patients with low back pain was identified when comparing the less expensive plain-film lumbar x-ray with more expensive imaging modalities such as MRI or CT scans 15.

Plain-film radiography of the lumbar spine is warranted in patients at risk of ventral vertebral fracture due to recent trauma or osteoporosis. CT or MRI should be considered for patients with significant risk factors for underlying serious conditions or progressive neurologic changes 1.

There are a number of treatments for low back pain, including exercises, medications and back supports.The aims of treatment include:

- Managing pain

- Exercise, limited rest and occasional use of over-the-counter pain medication effectively controls pain for most people.

- Try to use the lowest dose of medication possible to control your pain, rather than taking large doses.

- Reducing time away from work.

- Return to work as early as possible. Keeping your mind busy can prevent you from over-worrying and can provide support. It also prevents the growing difficulty of readjusting to work that occurs after long absences.

- Preventing the development of disability and dysfunction by staying active.

- Bed rest for more than a few days after your initial injury is bad for your back and can lead to chronic weakness and dysfunction in your spine.

- Activities keep you feeling healthy and well, in addition to provoking healing and altering your perception of pain.

- Minimizing the psychological distress that frequently accompanies back pain by staying positive.

- If you are concerned by your pain or anything else, discuss things with your family, friends or doctor. It is normal to be distressed by pain, even when you’re doctor has reassured you that there is no identifiable cause. Rely on your loved ones to be empathetic.

- Pain is an emotional experience – nerves carrying the sensation of pain directly interact with the emotion system (the hippocampus and limbic system) in the brain. Addressing and relieving anxiety and distress is consequently a key component of treatment of chronic pain.

- Prevent further injury.

- Take care of your back by adhering to your workplace’s safety regulations, by wearing lumbar support when appropriate and by avoiding activities that you know may provoke pain, like twisting, over-stretching or lifting heavy objects.

- Don’t take short cuts.

- Stay fit and maintain the strength in your abdominal muscles.

Self-care treatments that might help low back pain include:

- Cold packs. Initially, you might get relief from a cold pack placed on the painful area for up to 20 minutes several times a day. Use an ice pack or a package of frozen peas wrapped in a clean towel.

- Hot packs. After two to three days, apply heat to the areas that hurt. Use hot packs, a heat lamp or a heating pad on the lowest setting. If you continue to have pain, try alternating warm and cold packs.

- Stretching. Stretching exercises for your low back can help you feel better and might help relieve nerve root compression. Avoid jerking, bouncing or twisting during the stretch, and try to hold the stretch for at least 30 seconds.

- Over-the-counter medications. Pain relievers such as ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin IB, others) and naproxen sodium (Aleve) are sometimes helpful for low back pain.

If your pain doesn’t improve with self-care measures after several weeks, your doctor stronger medications or other therapies.

Very rarely, surgery can be used to treat back pain. However this will only be considered when:

- the cause of the back pain is known, for example, a slipped disc

- the potential benefits of surgery outweigh the risks

The non-surgical treatment options for back pain can generally produce a significant reduction in symptoms, allowing you to return to work and normal activities. However, it is important to keep in mind that the aim of treatment is always to reduce pain, as eliminating back pain altogether is notoriously difficult.

Most back pain gradually improves with home treatment and self-care, usually within a few weeks. See your doctor if your back pain:

- Your pain worsens or does not go away after 2 weeks.

- Is severe and doesn’t improve with rest.

- Spreads down one or both legs, especially if the pain extends below your knee.

- Causes weakness, numbness or tingling in one or both legs.

- You lose feeling in your back, legs, pelvis, genital area or your bladder or anus. This could make it hard to pee or have a bowel movement, or, alternatively, cause incontinence.

- Is accompanied by unexplained weight loss.

In rare cases, back pain can signal a serious medical problem. Seek immediate care if your back pain:

- Causes new bowel or bladder problems

- Is accompanied by a fever

- Follows an injury, trauma, a fall, blow to your back or other injury

- Cauda equina syndrome

- Cauda equina syndrome occurs when the bundle of nerve roots at the lower end of the spinal cord (cauda equina) are compressed and disrupt motor and sensory function to the lower extremities and bladder. Cauda equina syndrome can lead to incontinence and even permanent paralysis. Patients with this syndrome are often admitted to the hospital as a medical emergency.

- Cauda equina syndrome signs and symptoms may include:

- Progressive weakness. Motor weakness, sensory loss, or pain in one, or more commonly both legs

- Numbness or tingling in the groin (“saddle region” or saddle anesthesia)

- Difficulty to pass urine or use the bowels. Prolonged inability to pass urine can result in urine leaking uncontrollably

- Severe low back pain and sciatica.

- Pain may be sudden and severe or gradually develop over weeks

- Sexual dysfunction

- Fracture

- Age older than 50 years

- Osteoporosis

- Steroid use

- Trauma

- Infection

- Immunocompromise

- Intravenous drug use

- Night pain

- Steroid use

- Temperature above 100.4°F (38°C)

- Malignancy

- Age older than 50 years

- History of malignancy

- Progressive pain or night pain

- Unintended weight loss

The lower back anatomy

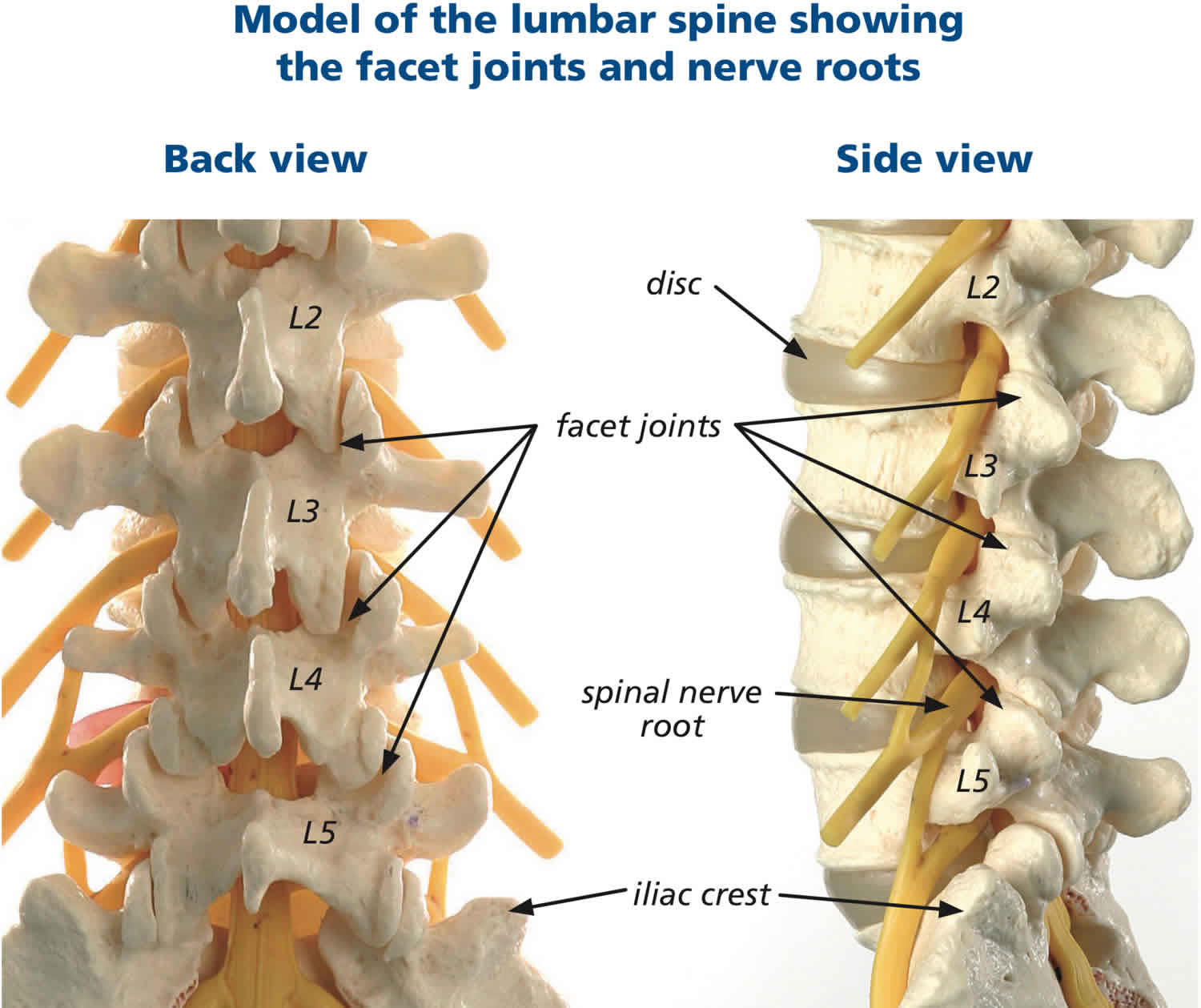

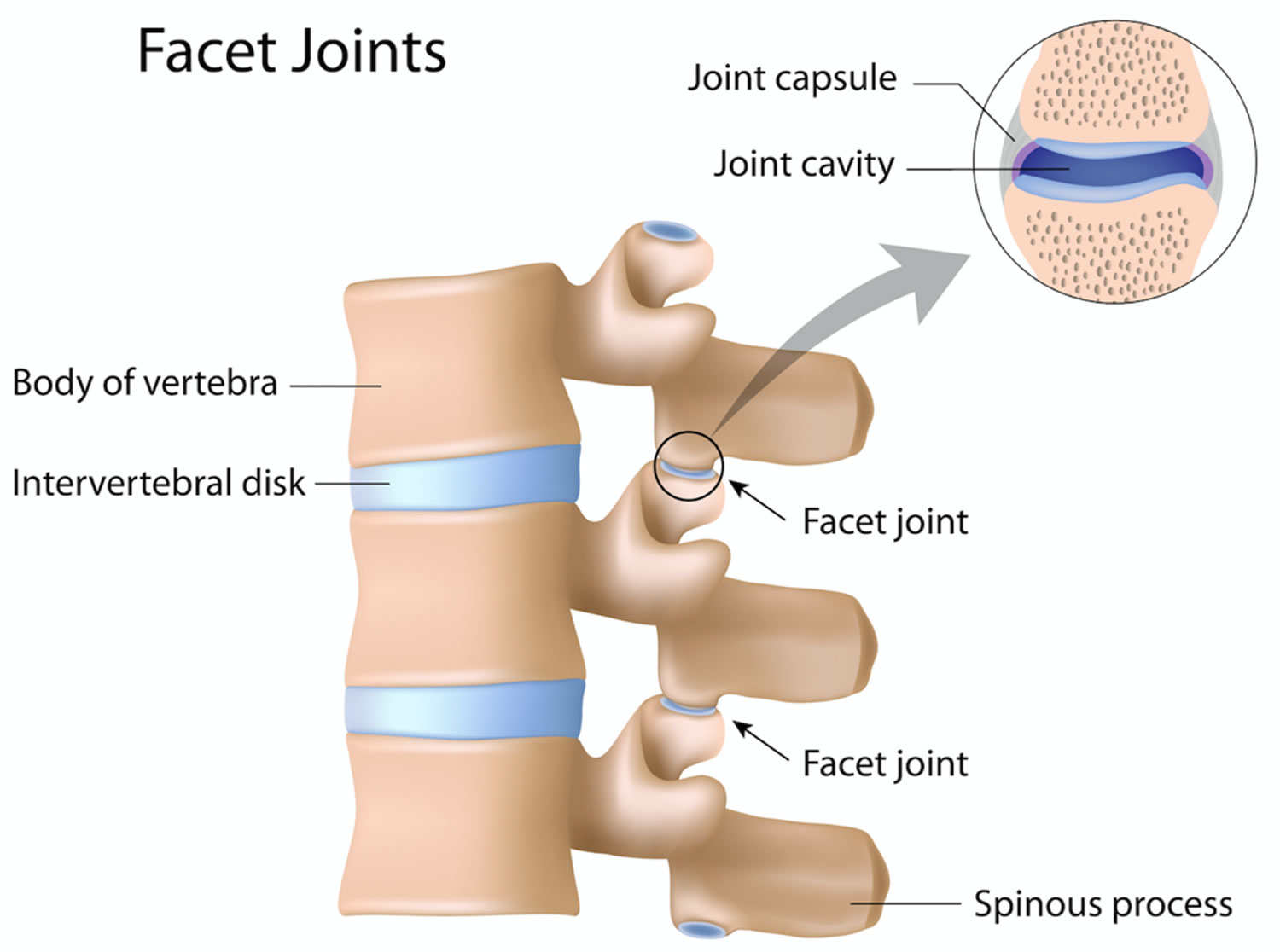

The lower back where most back pain occurs consists of five vertebrae (referred to as L1-L5) in the lumbar region, which supports much of the weight of the upper body. It has a slight inward curve known as lordosis. The fifth lumbar vertebrum is connected with the top of the sacrum. The vertebrae of the lumbar spine are connected in the back by facet joints, which allow for forward and backward extension, as well as twisting movements. The two lowest segments in the lumbar spine, L5-S1 and L4-L5, carry the most weight and have the most movement, making the area prone to injury.

The vertebral body (centrum) is a mass of spongy bone and red bone marrow covered with a thin shell of compact bone. This is the weight-bearing portion of the vertebra. Its rough superior and inferior surfaces provide firm attachment to the intervertebral discs. An intervertebral disc is a cartilaginous pad located between the bodies of two adjacent vertebrae. An intervertebral disc consists of an inner gelatinous nucleus pulposus surrounded by a ring of fibrocartilage, the anulus fibrosus. They help to bind adjacent vertebrae together, support the weight of the body, and absorb shock throughout the spinal column to cushion the bones as the body moves. Under stress—for example, when you lift a heavy weight—the discs bulge laterally. Excessive stress can crack the anulus fibrosus and cause the nucleus to ooze out. This is called a herniated disc (“ruptured” or “slipped” disc) and may put painful pressure on the spinal cord or a spinal nerve. Intervertebral discs in the lumbar region of the spine are most likely to herniate or degenerate, which can cause pain in the lower back, or radiating pain to the legs and feet.

The spinal cord travels from the base of the skull to the joint at T12-L1, where the thoracic spine meets the lumbar spine. At this segment, nerve roots branch out from the spinal cord, forming the cauda equina. Some lower back conditions may compress these nerve roots, resulting in pain that radiates to the lower extremities, known as radiculopathy. The lower back region also contains large muscles that support the back and allow for movement in the trunk of the body. These muscles can spasm or become strained, which is a common cause of lower back pain.

Posterior to the body of each vertebra is a triangular space called the vertebral foramen. The vertebral foramina collectively form the vertebral canal, a passage for the spinal cord. Each foramen

is bordered by a bony vertebral arch composed of two parts on each side: a pillarlike pedicle and platelike lamina. Extending from the apex of the arch, a projection called the spinous process is

directed posteriorly and downward. You can see and feel the spinous processes on a living person as a row of bumps along the spine. A transverse process extends laterally from the point where the pedicle and lamina meet. The spinous and transverse processes provide points of attachment for ligaments, ribs, and spinal muscles.

A pair of superior articular processes projects upward from one vertebra and meets a similar pair of inferior articular processes that projects downward from the vertebra above. Each process has a flat articular surface (facet) facing that of the adjacent vertebra. These processes restrict twisting of the vertebral column, which could otherwise severely damage the spinal cord.

When two vertebrae are joined, they exhibit an opening between their pedicles called the intervertebral foramen. This allows passage for spinal nerves that connect with the spinal cord at regular intervals. Each foramen is formed by an inferior vertebral notch in the pedicle of the upper vertebra and a superior vertebral notch in the pedicle of the lower one.

Figure 1. Spinal cord segments

Figure 2. Lumbar vertrebrum (looking from above)

Figure 3. Lumbar vertebrae anatomy (looking from behind and from the side)

Figure 4. Lumbar spine facet joints

Figure 5. Herniated disc (the rubbery disks that lie between the vertebrae in your spine consist of a soft center (nucleus) surrounded by a tougher exterior (annulus). A herniated disk occurs when a portion of the nucleus pushes through a crack in the annulus. Symptoms may occur if the herniation compresses a nerve.)

Figure 6. Spinal stenosis (spinal stenosis occurs when the space within the spinal canal or around the nerve roots becomes narrowed)

What is sciatica?

Sciatica also known as nerve root pain or radiculopathy, refers to pain that radiates along the path of the sciatic nerve, which branches from your lower back through your hips and buttocks and down each leg. Typically, sciatica affects only one side of your body. Pain that radiates from your lower (lumbar) spine to your buttock and down the back of your leg is the hallmark of sciatica. You might feel the discomfort almost anywhere along the nerve pathway, but it’s especially likely to follow a path from your low back to your buttock and the back of your thigh and calf.

Sciatica may feel like a bad leg cramp that lasts for weeks before it goes away. It may be come on suddenly and can persist for days or weeks. You may experience the following:

- Pain in your lower back or hip that radiates down from your buttock to the back of one thigh and into your leg. Especially when you sit, sneeze or cough.

- Weakness,

- Pins and needles, numbness, or a burning or tingling sensation down your leg.

- Loss of bladder or bowel control – sign of cauda equina syndrome, a rare but serious condition that requires emergency care. If you experience either of these symptoms, seek medical help immediately.

Sciatica is a very common condition, especially in men and women between the ages of 30 and 50.

Sciatica most commonly occurs when a herniated disk or bulging disk, bone spur on the spine or narrowing of the spine (spinal stenosis) compresses part of the nerve. This causes inflammation, pain and often some numbness in the affected leg.

The pain usually starts in the lower back or hips and then radiates into the back of the thighs and can spread down into the legs with the possibility of affecting the feet. This is the path of the sciatic nerve and it’s branches – it is the longest nerve in your body and runs from your spinal cord to your buttock and hip area and down the back of each leg.

Sciatica is a symptom (what you feel), not a disorder (the cause of the problem). The radiating pain of sciatica signals another problem involving the compression or irritation of nerves as they exit the spinal canal (space which the spinal cord travels).

When lower back pain radiates into the buttocks and thighs, it’s often confused with sciatica, a relatively uncommon condition.

If you have sciatica, your leg pain will usually be more severe than your back pain. You’re likely to feel it below the knee as well, and it may even radiate to your foot and toes. And you’ll probably feel a tingling, pins-and-needles sensation in your legs or possibly some numbness.

With severe sciatic nerve pain, you may have numbness in your groin or genital area as well. You may even find that it’s hard to urinate or have a bowel movement.

If you think you have sciatica, see your healthcare provider. See your doctor immediately if you feel weakness in one or both legs, or lose sensation in your legs, groin, bladder, or anus. This may make it hard to pee or have a bowel movement, or, alternatively, cause incontinence.

Although the pain associated with sciatica can be severe, most cases resolve with non-operative treatments in a few weeks. People who have severe sciatica that’s associated with significant leg weakness or bowel or bladder changes might be candidates for surgery.

Mild sciatica usually goes away over time. See your doctor if self-care measures fail to ease your symptoms or if your pain lasts longer than a week, is severe or becomes progressively worse. Get immediate medical care if:

- You have sudden, severe pain in your low back or leg and numbness or muscle weakness in your leg

- The pain follows a violent injury, such as a traffic accident

- You have trouble controlling your bowels or bladder

Lower back pain pregnancy

Most women who are pregnant have some degree of lower back pain. During pregnancy, the ligaments in your body naturally become softer and stretch to prepare you for labor. This can put a strain on the joints of your lower back and pelvis, which can cause back pain. The extra weight of your uterus and the increasing size of the hollow in your lower back can also add to the problem. Women who had prior back pain, are overweight, unfit or smoke are more likely to experience lower back pain or sciatica during pregnancy.

You might have back pain in early pregnancy, but it usually starts during the second half of pregnancy and can get worse as your pregnancy progresses. It may persist after your baby arrives, but postpartum back pain usually goes away within a few months.

However, back pain in pregnancy could also be a sign of preterm labor.

See your doctor if:

- Your pain worsens or does not go away after 2 weeks. Back pain could be a sign of preterm labor.

- You lose feeling in your back, legs, pelvis, or genital area.

- You have a fever, a burning feeling when you urinate or vaginal bleeding. You may have a urinary tract infection (UTI) or kidney infection.

- You have an injury or trauma that results in back pain.

You’re at higher risk for lower back pain during pregnancy if:

- You’ve had this kind of pain before, either before you got pregnant or during a previous pregnancy

- You have a sedentary lifestyle

- You are not very flexible

- You have weak back and weak abdominal muscles

- You are carrying twins (or more)

- You have a high body mass index (BMI)

- You’ve had spinal fusion in the past for adolescent scoliosis

More than 60 percent of pregnant women experience lower back pain, particularly posterior pelvic pain and lumbar pain 16. Posterior pelvic pain is felt in the back of your pelvis. It’s the most common type of lower back pain during pregnancy, though some women have lumbar pain as well 16.

You may feel posterior pelvic pain as deep pain on one or both sides of your buttocks or at the back of your thighs. It may be triggered by walking, climbing stairs, getting in and out of the tub or a low chair, rolling over in bed, or twisting and lifting.

Certain positions may make posterior pelvic pain worse, for example when you’re sitting in a chair and leaning forward at a desk or otherwise bent at the waist. Women with posterior pelvic pain are also more likely to have pain over their pubic bone.

Lumbar pain occurs in the area of the lumbar vertebrae in your lower back, higher on your body than posterior pelvic pain. It probably feels similar to the lower back pain you may have experienced before you were pregnant. You feel it over and around your spine approximately at waist level.

You also might have pain that radiates to your legs. Sitting or standing for long periods of time and lifting usually make it worse, and it tends to be more intense at the end of the day.

There are several things you can do to help prevent low back pain during pregnancy from happening, and to help you cope with an aching back if it does occur.

- It is important to avoid lifting heavy objects. When lifting or picking up something from the floor, be sure to bend your knees and keep your back straight and lift things from a crouching position to minimize the stress on your back. This isn’t the time to risk throwing your back out, so let someone else lift heavy things and reach for high objects. Avoid twisting movements too, and activities that require you to bend and twist, like vacuuming and mopping. If there’s no one else to do these chores, move your whole body rather than twisting or reaching to get to out-of-the-way spots.

- Take care when getting out of bed, which becomes more difficult once your belly starts to bulge in your second or third trimester. You can handle it by doing what’s most comfortable and leaves you steady on your feet. One technique is to bend your legs at your knees and hips when you roll to the side, and use your arms to push yourself up as you dangle your lower legs over the side of the bed. Take your time getting up, and don’t forget that your center of gravity has changed. Don’t hesitate to ask your partner for help getting into and out of bed.

- Move your feet when turning around to avoid twisting your spine.

- Be aware of movements that make the pain worse. If you have posterior pelvic pain, try to limit activities like climbing stairs, for example. And avoid any exercise that requires extreme movements of your hips or spine.

- Wear comfortable shoes with low heels (not flats) as these have good arch support and allow your weight to be evenly distributed. Put away your high heels for a while because as your belly grows and your balance shifts, high heels will throw your posture even more out of whack and increase your chances of stumbling and falling.

- Work at a surface high enough to prevent you stooping

- Try to balance the weight between two bags when carrying shopping

- Divide up the weight of items you have to carry. Carrying a shopping bag in each hand with half the weight in each is much better than the uneven stress of carrying one heavier bag.

- Sit with your back straight and well supported. Supporting your feet with a footstool can prevent lumbar pain, as can using a small pillow (called a lumbar roll) behind your lower back. Take frequent breaks from sitting. Get up and walk around at least every hour or so.

- Avoid standing or sitting for long periods. If you need to stand all day, rest one foot on a low step stool. Take breaks, and try to find time to rest lying on your side while supporting your upper leg and abdomen with pillows.

- Make sure you get enough rest, particularly later in pregnancy. To get a good night’s rest, try sleeping on your side with one or both knees bent and a pillow between your legs. As your pregnancy advances, use another pillow or wedge to support your abdomen. Add a mattress topper or consider switching to a firmer mattress to support your back.

- Pay attention to your posture. Try to have good posture:

- Stand up straight. This gets harder to do as your body changes, but try to keep your bottom tucked in and your shoulders back. Pregnant women tend to slump their shoulders and arch their back as their belly grows, which puts more strain on the spine.

- If you sit most of the day, be sure to sit up straight.

- It’s equally important to avoid standing for too long.

- A firm mattress can also help to prevent and relieve low back pain. If your mattress is too soft, put a piece of hardboard under it to make it firmer.

- Check with your doctor before beginning an exercise program because in some situations, you may have to limit your activity or skip exercise altogether. If you get the go-ahead to work out, some activities that may help ease your back pain include:

- Aqua aerobics (gentle exercise in water)

- Acupuncture. Acupuncture may reduce the intensity of back pain during pregnancy. Some studies have demonstrated acupuncture to be superior to physical therapy alone and more effective than standard treatment in many cases. Make sure, however, that the practitioner you choose knows how to do prenatal acupuncture and the areas to avoid.

- Massage. Prenatal massage by a trained therapist may provide some relief and relaxation. Alternatively, ask your partner or a friend to gently rub or knead your back. (Most insurance companies don’t cover therapeutic massage unless you have a referral from your healthcare provider.)

- Hot packs

- Regular exercise, including:

- Weight training to strengthen the muscles that support your back and legs, including your abdominal muscles.

- Stretching exercises to increase the flexibility in the muscles that support your back and legs. Be careful to stretch gently because stretching too quickly or too much can put further strain on your joints, which become looser in pregnancy. Prenatal yoga is one good way to stay limber, and it can improve your balance, too.

- Swimming is another great exercise for pregnant women because it strengthens your abdominal and lower back muscles, and the buoyancy of the water takes the strain off your joints and ligaments. Consider signing up for a prenatal water exercise class if one is available in your community. These can be very relaxing, and research suggests that water exercise may reduce the intensity of back pain during pregnancy.

- Walking is another low-impact option to consider. It’s also easy to make it a part of your daily routine.

- Pelvic tilts can ease lumbar pain by stretching and strengthening your muscles. Here’s how to do them: Get on your hands and knees, with your arms shoulder-width apart and knees hip-width apart. Keep your arms straight, but don’t lock your elbows. Slowly arch your back and tuck your buttocks under as you breathe in. Relax your back into a neutral position as you breathe out. Repeat three to five times at your own pace.

See your doctor if:

- Your back pain worsens or does not go away after 2 weeks. Back pain could be a sign of preterm labor.

- Your back pain is severe, gets progressively worse, or is caused by trauma.

- You lose feeling in your back, legs, pelvis, genital area, bladder or anus. This could make it hard to pee or have a bowel movement, or, alternatively, cause incontinence.

- Your back pain is accompanied by a fever, a burning feeling when you urinate, or vaginal bleeding. You may have a urinary tract infection (UTI) or kidney infection.

- You have an injury or trauma that results in back pain.

- You have lost feeling in one or both legs, or you suddenly feel uncoordinated or weak.

- You have pain in your lower back or in your side just under your ribs, on one or both sides. This can be a sign of a kidney infection, especially if you have a fever, nausea, or blood in your urine.

- You have suddenly worsened lower back pain in the late second or early third trimester. This can be a sign of preterm labor, especially if you didn’t have intense back pain previously.

Know the signs of labor and if you experience any of these symptoms, DO NOT wait for them to just go away. Seek immediate medical care. Preterm labor is any labor before 37 weeks gestation. The signs of labor are:

- Change in your vaginal discharge (watery, mucus or bloody) or more vaginal discharge than usual.

- Pressure in your pelvis or lower belly, like your baby is pushing down.

- Constant low, dull backache.

- Belly cramps with or without diarrhea.

- Regular or frequent contractions that make your belly tighten like a fist. The contractions may or may not be painful.

- Your water breaks.

Lower back pain during pregnancy causes

There are several causes of low back pain during pregnancy. These are due to changes that occur in your body.

- Pregnancy hormones. Many hormones change when you are pregnant for different reasons. Later in your pregnancy, hormones increase to relax the muscles and ligaments in your pelvis that attach your pelvic bones to your spine. This prepares your body for labor. This can make you feel less stable and cause pain when you walk, stand, sit for long periods, roll over in bed, get out of a low chair or the tub, bend, or lift things. If your muscles and ligaments become too loose, it can lead to back pain.

- Posture. Pregnancy can alter your center of gravity. The way you move, sit, and stand can cause pain to your back and other parts of your body. A compressed nerve due to poor posture also can cause low back pain.

- Pressure on back muscles. As your baby grows, your uterus expands and becomes heavier. This puts added weight on your back muscles. You may find yourself leaning backward or arching your low back. The pressure can lead to low back pain or stiffness.

- Weakness in stomach muscles. Your growing baby also puts pressure on your stomach muscles. This can cause them to stretch and weaken. Your stomach and back muscles are connected. Your back muscles have to work harder to offset your belly.

- Stress. Feeling stressed is common during pregnancy because pregnancy is a time of many changes. Physical discomforts and other changes in your daily life can cause stress during pregnancy. Anxiety and built-up tension can make your back muscles tight or stiff.

Lower back pain during pregnancy prevention

To help prevent back pain during pregnancy, be mindful of how you sit, stand, sleep, and move.

- Sit in a way that supports your back. Choose a lumbar chair or place a pillow behind your low back. Try propping your feet up to increase blood flow and prevent slouching.

- Sit and stand up straight. Try to keep your back in line with your bottom and legs rather than arch your low back. Do not sit or stand in the same position for a prolonged time. It could pinch a nerve. Do not lock your knees. If you have to stand for long periods, try resting one foot at a time on a box or stool.

- Wear low-heeled shoes that are comfortable and provide support to your whole body. It may help to use arch support inserts. Avoid shoes with heels that can knock you off balance.

- Sleep with a mattress that isn’t too soft and offers support. When you are pregnant, it is best to sleep on your side. Place pillows under your stomach and between your legs for added support. Try to avoid sleeping on your back. This can put pressure on your uterus and cut off blood flow to your baby.

- Do not twist or make sudden movements that could strain your back or stomach muscles.

- Do not lift things by bending forward. Instead, keep your back straight and lift with your legs instead of your back. Be careful not to lift or carry too much weight at once.

- Get plenty of exercise. This will help strengthen your back and stomach muscles and improve your posture. Talk to your doctor about what type of exercise is safe. Walking and swimming often are fine. If you were very active before pregnancy, you may be able to continue doing the same level of activity. Certain moves and stretches, such as kegel exercises, also prepare you for labor.

- Wear maternity pants. The wide elastic waistband provides extra support.

How can you reduce stress during pregnancy?

Here are some ways to help you reduce stress during pregnancy:

- Know that the discomforts of pregnancy are only temporary. Ask your provider about how to handle these discomforts.

- Stay healthy and fit. Eat healthy foods, get plenty of sleep and exercise (with your provider’s OK). Exercise can help reduce stress and also helps prevent common pregnancy discomforts.

- Cut back on activities you don’t need to do. For example, ask your partner to help with chores around the house.

- Try relaxation activities, like prenatal yoga or meditation. They can help you manage stress and prepare for labor and birth.

- Take a childbirth education class so you know what to expect during pregnancy and when your baby arrives. Practice the breathing and relaxation methods you learn in your class.

- If you’re working, plan ahead to help you and your employer get ready for your time away from work. Use any time off you may have to get extra time to relax.

The people around you may help with stress relief too. Here are some ways to reduce stress with the help of others:

- Have a good support network, which may include your partner, family and friends. Or ask your provider about resources in the community that may be helpful.

- Figure out what’s making you stressed and talk to your partner, a friend, family or your provider about it.

- If you think you may have depression or anxiety talk to your provider right away. Getting treatment early is important for your health and your baby’s health.

- Ask for help from people you trust. Accept help when they offer. For example, you may need help cleaning the house, or you may want someone to go with you to your prenatal visits.

Lower back pain during pregnancy treatment

If you have low back pain during pregnancy, these tips can help relieve soreness and stiffness:

- Apply heat or a cold compress to your back. Avoid putting extreme temperatures on your stomach.

- Take acetaminophen (paracetamol).

- Find ways to relieve stress. Learn breathing exercises or take a prenatal yoga class.

- Get a prenatal massage from a certified therapist.

- Exercise such as weight training, stretching, swimming, walking, and pelvic tilts may be helpful. Working on your posture, heat or cold, and prenatal massage might also ease the pain.

- Physical therapy can relieve pain and prevent recurring episodes of lower back pain.

- Ask your doctor about alternative medicine. This could include acupuncture or a chiropractic adjustment. It could also include osteopathic manipulation. Your muscles and joints are moved through stretching and using gentle pressure.

The gentle exercises below may help ease backache in pregnancy.

- Stretches for lower backache:

- sit with your bottom on your heels with your knees apart

- lean forward towards the floor, resting your elbows on the ground in front of you

- slowly stretch your arms forward

- hold for a few seconds

- Stretches for middle backache:

- go down on your hands and knees

- draw in lower tummy

- tuck your tail under

- hold for a few seconds

- gently lower your back down as far as feels comfortable

- Stretches for pain in the shoulder blades and upper back:

- sit on a firm chair

- brace your abdominal muscles

- interlock your fingers and lift your arms overhead

- straighten your elbows and turn your palms upwards

- hold for a few seconds

Note: If back pain persists, changes or becomes severe, see your doctor or midwife for advice. They may advise you to see a physiotherapist. At any stage, if the back pain is associated with any blood loss from the vagina, seek medical advice urgently.

Treatment of back injury during pregnancy

If you injure your back while you are pregnant, simple exercises and using back support are usually enough to fix the injury. In very rare cases, pregnant women can have a serious injury such as a herniated disc. In this case you might need surgery. Back surgery is usually safe, however, both for you and your baby during pregnancy.

Many women have a pre-existing back condition before they become pregnant, such as scoliosis, spondylolisthesis or a lumbar disc condition. Sometimes your back problems get better during pregnancy, but sometimes they get worse. It’s important to mention any back problems to the medical team who are looking after you.

Talk to your doctor if you need to take medicine to control back pain. Acetaminophen (paracetamol) is one of the safest painkillers during pregnancy. Do not take aspirin or non-steroidal anti-inflammatories such as ibuprofen while you are pregnant.

Your back injury should not affect labor or pain relief during labor. It is also usually possible to have an epidural if you have a back injury. Tell the hospital about your condition because there are different positions you can use to ease back pain during labor.

Lower back pain causes

Most acute low back pain is mechanical in nature, meaning that there is a disruption in the way the components of the back (the spine, muscle, intervertebral discs, and nerves) fit together and move. Some examples of mechanical causes of low back pain include:

- Congenital (condition you are born with)

- Skeletal irregularities such as scoliosis (a curvature of the spine), lordosis (an abnormally exaggerated arch in the lower back), kyphosis (excessive outward arch of the spine), and other congenital anomalies of the spine.

- Spina bifida which involves the incomplete development of the spinal cord and/or its protective covering and can cause problems involving malformation of vertebrae and abnormal sensations and even paralysis.

- Injuries

- Sprains (overstretched or torn ligaments), strains (tears in tendons or muscle), and spasms (sudden contraction of a muscle or group of muscles)

- Traumatic Injury such as from playing sports, car accidents, or a fall that can injure tendons, ligaments, or muscle causing the pain, as well as compress the spine and cause discs to rupture or herniate.

- Degenerative problems

- Intervertebral disc degeneration which occurs when the usually rubbery discs wear down as a normal process of aging and lose their cushioning ability.

- Spondylosis the general degeneration of the spine associated with normal wear and tear that occurs in the joints, discs, and bones of the spine as people get older.

- Arthritis or other inflammatory disease in the spine, including osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis as well as spondylitis, an inflammation of the vertebrae.

- Nerve and spinal cord problems

- Spinal nerve compression, inflammation and/or injury

- Sciatica (also called radiculopathy), caused by something pressing on the sciatic nerve that travels through the buttocks and extends down the back of the leg. People with sciatica may feel shock-like or burning low back pain combined with pain through the buttocks and down one leg.

- Spinal stenosis, the narrowing of the spinal column that puts pressure on the spinal cord and nerves

- Spondylolisthesis, which happens when a vertebra of the lower spine slips out of place, pinching the nerves exiting the spinal column

- Herniated or ruptured discs can occur when the intervertebral discs become compressed and bulge outward

- Infections involving the vertebrae, a condition called osteomyelitis; the intervertebral discs, called discitis; or the sacroiliac joints connecting the lower spine to the pelvis, called sacroiliitis

- Cauda equina syndrome occurs when a ruptured disc pushes into the spinal canal and presses on the bundle of lumbar and sacral nerve roots. Permanent neurological damage may result if this syndrome is left untreated.

- Osteoporosis (a progressive decrease in bone density and strength that can lead to painful fractures of the vertebrae)

- Non-spine sources

- Kidney stones can cause sharp pain in the lower back, usually on one side

- Endometriosis (the buildup of uterine tissue in places outside the uterus)

- Fibromyalgia (a chronic pain syndrome involving widespread muscle pain and fatigue)

- Tumors that press on or destroy the bony spine or spinal cord and nerves or outside the spine elsewhere in the back

- Pregnancy (back symptoms almost always completely go away after giving birth)

Red flags (see boxed warnings above) can help rule out serious underlying causes 17, 9. A systematic review showed that age older than 50 years, steroid use, and trauma are red flags for fracture 9. Although a number of red flags for the presence of a tumor have been suggested, only a history of malignancy is supported by evidence 17.

Selected differential diagnosis for chronic low back pain 1:

- Abdominal aortic aneurysm

- Ankylosing spondylitis

- Epidural abscess

- Fracture of the pars interarticularis

- Metastatic malignancy

- Osteoarthritis of the hip

- Osteoporosis

- Piriformis syndrome

- Radiculitis

- Sacroiliac joint dysfunction

- Traumatic fracture

- Trochanteric bursitis

- Varicella zoster virus

Risk factors for getting low back pain

Anyone can develop back pain, even children and teens. These factors might put you at greater risk of developing back pain:

- Age. Back pain is more common as you get older, starting around age 30 or 40. Loss of bone strength from osteoporosis can lead to fractures, and at the same time, muscle elasticity and tone decrease. The intervertebral discs begin to lose fluid and flexibility with age, which decreases their ability to cushion the vertebrae. The risk of spinal stenosis also increases with age.

- Lack of exercise. Back pain is more common among people who are not physically fit. Weak, unused muscles in your back and abdomen might lead to back pain. “Weekend warriors”—people who go out and exercise a lot after being inactive all week—are more likely to suffer painful back injuries than people who make moderate physical activity a daily habit. Studies show that low-impact aerobic exercise can help maintain the integrity of intervertebral discs.

- Excess weight. Excess body weight puts extra stress on your back and can lead to low back pain.

- Genetics. Some causes of back pain, such as ankylosing spondylitis (a form of arthritis that involves fusion of the spinal joints leading to some immobility of the spine), have a genetic component.

- Diseases. Some types of arthritis and cancer can contribute to back pain.

- Previous injury or pain in the spine or other joints involved in walking, especially the hips and knees.

- Work that involves heavy manual labor. Performing activities that involve heavy lifting, pushing, or pulling, particularly when it involves twisting or vibrating the spine, can lead to injury and back pain. Working at a desk all day can contribute to pain, especially from poor posture or sitting in a chair with not enough back support.

- Improper lifting. Using your back instead of your legs can lead to back pain.

- Psychological conditions. People prone to depression and anxiety appear to have a greater risk of back pain. Interestingly, the risk of developing chronic low back pain is more related to psychosocial factors than to the physical cause of the back pain. For example, someone who dislikes their work and is very concerned about their back is more likely to develop long-term pain than someone who is optimistic and can’t wait to return to work.

- Mental health. Anxiety and depression can influence how closely one focuses on their pain as well as their perception of its severity. Pain that becomes chronic also can contribute to the development of such psychological factors. Stress can affect the body in numerous ways, including causing muscle tension.

- Smoking. Smokers have increased rates of back pain. This may occur because smoking prompts more coughing, which can lead to herniated disks. Smoking can also decrease blood flow to the spine and increase the risk of osteoporosis.

- Backpack overload in children. A backpack overloaded with schoolbooks and supplies can strain the back and cause muscle fatigue.

Low back pain prevention

You might avoid back pain or prevent its recurrence by improving your physical condition and learning and practicing proper body mechanics.

To keep your back healthy and strong:

- Exercise. Regular low-impact aerobic activities — those that don’t strain or jolt your back — can increase strength and endurance in your back and allow your muscles to function better. Walking and swimming are good choices. Talk with your doctor about which activities you might try.

- Build muscle strength and flexibility. Abdominal and back muscle exercises, which strengthen your core, help condition these muscles so that they work together like a natural corset for your back.

- Maintain a healthy weight. Being overweight strains back muscles. If you’re overweight, trimming down can prevent back pain.

- Quit smoking. Smoking increases your risk of low back pain. The risk increases with the number of cigarettes smoked per day, so quitting should help reduce this risk.

Avoid movements that twist or strain your back. Use your body properly:

- Stand smart. Don’t slouch. Maintain a neutral pelvic position. If you must stand for long periods, place one foot on a low footstool to take some of the load off your lower back. Alternate feet. Good posture can reduce the stress on back muscles.

- Sit smart. Choose a seat with good lower back support, armrests and a swivel base. Placing a pillow or rolled towel in the small of your back can maintain its normal curve. Keep your knees and hips level. Change your position frequently, at least every half-hour.

- If long periods seated at a desk are giving you a sore back, your office chair may need adjusting to give you better back support — or you may even need a new chair designed to reduce back pain. Sitting on a fitness ball for office work is not recommended. To stay upright on a fitness ball, you have to make constant, small adjustments in muscle tension and weight distribution. This effort helps you achieve the benefits of core-strengthening exercises performed with a fitness ball. Prolonged balancing on a fitness ball during a full day of work, however, may lead to increased fatigue and discomfort in your back.

- Lift smart. Avoid heavy lifting, if possible, but if you must lift something heavy, let your legs do the work. Keep your back straight — no twisting — and bend only at the knees. Hold the load close to your body. Find a lifting partner if the object is heavy or awkward.

Because back pain is so common, numerous products promise prevention or relief. But there’s no definitive evidence that special shoes, shoe inserts, back supports, specially designed furniture or stress management programs can help. In addition, there doesn’t appear to be one type of mattress that’s best for people with back pain. It’s probably a matter of what feels most comfortable to you.

Lower back pain symptoms

Low back pain varies by person. It may be a dull ache or a sharp, stabbing pain. It could be acute (short-term) or chronic (ongoing). You may have pain in other parts of your body as well as your back.

Back pain can be persistent or intermittent, worse with activity or rest, associated with specific movements or be completely inexplicable. The different patterns of pain reflect the different causes.

See your doctor if:

- Your pain goes down your leg below your knee.

- Your leg, foot, groin, or rectum feel numb.

- You have fever, chills, nausea, vomiting, stomach pain, or weakness.

- You have trouble going to the bathroom.

- Your pain was caused by an injury.

- Your pain is so intense that you can’t move around.

- Your pain doesn’t improve or gets worse after 2 to 3 weeks.

Low back pain possible complications

Low back pain can make any movement at the spine painful, rendering normal activities like sitting or walking almost impossible.

If you have prolonged periods of rest associated with episodes of pain you can develop significant dysfunction in the musculoskeletal system in general. This can be a combination of:

- Deconditioning. Muscles that are not used regularly become weak and ‘lazy’. This softening of muscles leads of poorly balanced forces acting around the joints in the body.

- Joints that are not moved can become stiff and weak.

- Prolonged bed rest can lead to weakness in the bones. This usually only occurs after very long periods of reduced activity.

Lower back pain diagnosis

Your doctor may ask you some of the following questions:

- What are your symptoms? When are they worse?

- When and how did your symptoms start?

- What has changed since?

- Has there been any bowel or bladder changes?

- What makes the symptoms better or worse?

- What investigations have been done by doctors in the past to evaluate the cause of your symptoms?

- Have you had treatment for your symptoms, such as medications, steroid injections and surgery? Were they effective?

- Have you tried any other alternative therapy for your problems?

- Do you have any other medical problems?

Your doctor may also want to test the following:

- Your gait – by asking you to walk

- Power of your legs

- Range of motion of your back and leg joints

- Reflexes

- Sensation

- Straight Leg Test – this may reproduce your symptoms. Your doctor will ask you to keep your knee straight while bending your hip. He or she may also bend your ankle. Let your doctor know if you feel pain or numbness.

Your doctor will examine your back and assess your ability to sit, stand, walk and lift your legs. Your doctor might also ask you to rate your pain on a scale of zero to 10 and talk to you about how well you’re functioning with your pain. These assessments help determine where the pain comes from, how much you can move before pain forces you to stop and whether you have muscle spasms. They can also help rule out more-serious causes of back pain.

Many people have herniated disks or bone spurs that will show up on X-rays and other imaging tests but have no symptoms. So doctors don’t typically order these tests unless your pain is severe, or it doesn’t improve within a few weeks.

If there is reason to suspect that a specific condition is causing your back pain, your doctor may suggest a few tests including:

- X-ray. To detect evidence of spondylolisthesis (misalignment of the vertebrae), an overgrowth of bone (bone spur), narrowed disks, or evidence of erosion that may suggest a tumor affecting the spine. These images alone won’t show problems with your spinal cord, muscles, nerves or disks.

- CT scan. Allows visualization of the spinal cord and nerves. When a CT is used to image the spine, you may have a contrast dye injected into your spinal canal before the X-rays are taken — a procedure called a CT myelogram. The dye then circulates around your spinal cord and spinal nerves, which appear white on the scan.

- MRI scan. An MRI produces detailed images of the vertebral disks, ligaments, and muscles, as well as the presence of tumors. MRI scan uses a powerful magnet and radio waves to produce cross-sectional images of your back. During the test, you lie on a table that moves into the MRI machine.

- Blood tests. These can help determine whether you have an infection or other condition that might be causing your pain.

- Bone scan. In rare cases, your doctor might use a bone scan to look for bone tumors or compression fractures caused by osteoporosis. A small amount of radioactive material is injected into your bloodstream and collects in the bones, particularly in areas with some abnormality. Scanner-generated images can identify specific areas of irregular bone metabolism or abnormal blood flow, as well as to measure levels of joint disease.

- Electromyography (EMG). This test measures the electrical impulses produced by the nerves and the responses of your muscles. Electromyography (EMG) can confirm nerve compression caused by herniated disks or narrowing of your spinal canal (spinal stenosis).

- Evoked potential studies involve two sets of electrodes—one set to stimulate a sensory nerve, and the other placed on the scalp to record the speed of nerve signal transmissions to the brain.

- Nerve conduction studies (NCS) also use two sets of electrodes to stimulate the nerve that runs to a particular muscle and record the nerve’s electrical signals to detect any nerve damage.

Lower back pain treatment

For most people, acute back pain responds to self-care measures or gets better on its own within a month, but bed rest isn’t recommended as motion aids recovery. Continue your activities as much as you can tolerate (lying down can weaken your back muscles and make back pain worse). Try light activity, such as walking and activities of daily living. Stop activity that increases pain, but don’t avoid activity out of fear of pain. However, everyone is different, and back pain is a complex condition. For many, the pain doesn’t go away for a few months, but only a few have persistent, severe pain.

Self-care treatments that might help acute back pain include:

- Cold packs. Initially, you might get relief from a cold pack placed on the painful area for up to 20 minutes several times a day. Use an ice pack or a package of frozen peas wrapped in a clean towel.

- Hot packs. After two to three days, apply heat to the areas that hurt. Use hot packs, a heat lamp or a heating pad on the lowest setting. If you continue to have pain, try alternating warm and cold packs.

- Stretching. Stretching exercises for your low back can help you feel better and might help relieve nerve root compression. Avoid jerking, bouncing or twisting during the stretch, and try to hold the stretch for at least 30 seconds.

- Over-the-counter medications. Pain relievers such as ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin IB, others) and naproxen sodium (Aleve) are sometimes helpful for low back pain.

If your pain doesn’t improve with self-care measures after several weeks, your doctor stronger medications or other therapies.

Chronic back pain is most often treated with a stepped care approach, moving from simple low-cost treatments to more aggressive approaches. Specific treatments may depend on the identified cause of the back pain.

Figure 7. Suggested approach for patient with chronic low back pain

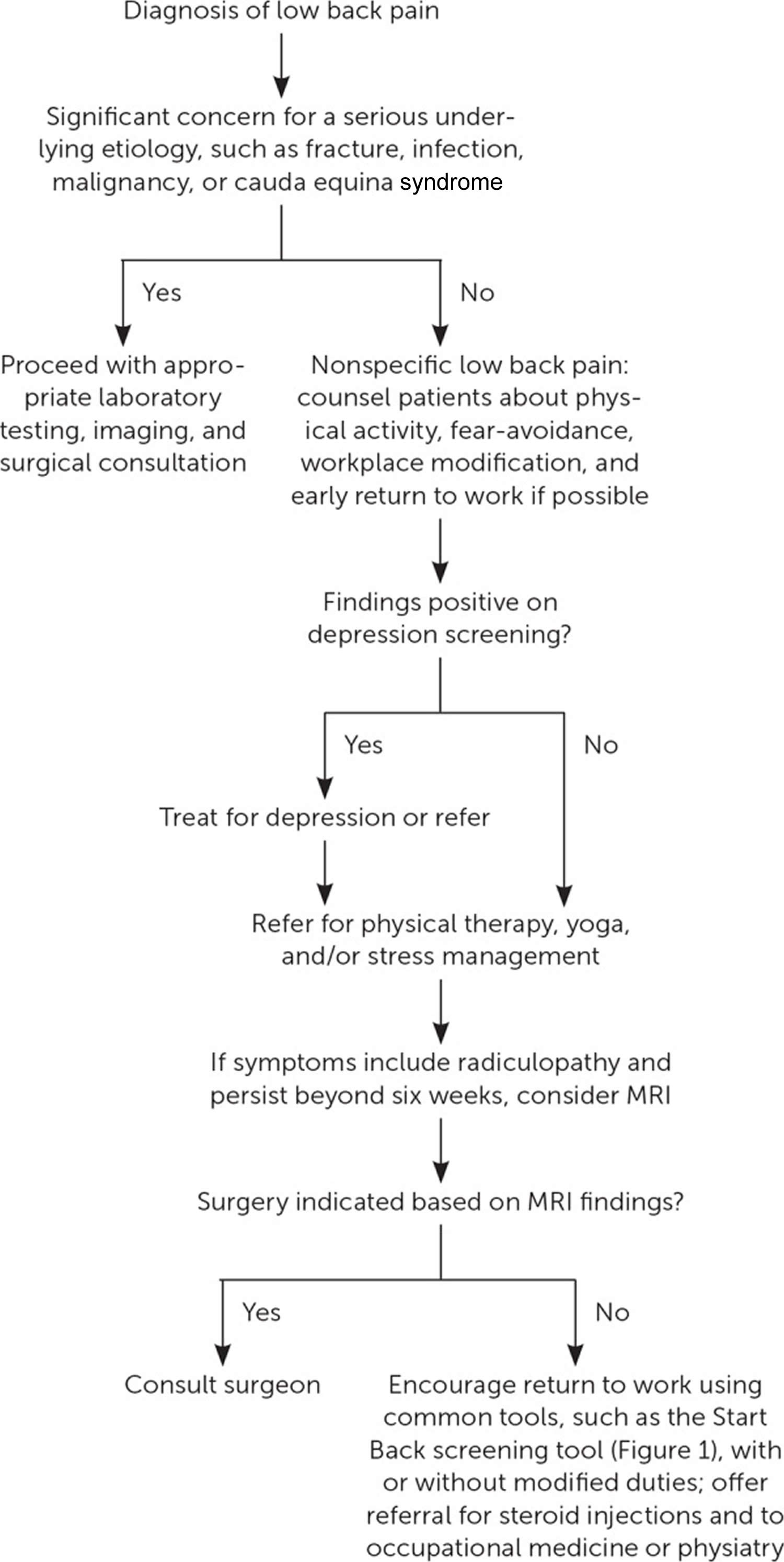

[Source 1 ]Figure 8. Management of nonspecific low back pain

Footnote: Low back pain is categorized as nonspecific low back pain without radiculopathy, low back pain with radicular symptoms, or secondary low back pain with a spinal cause. Nonspecific low back pain is a diagnosis of exclusion that is made once concerning causes are ruled out. Nearly 5% of all outpatient medical visits are for nonspecific low back pain 18.

MRI = magnetic resonance imaging

[Source 19 ]Stretching for lower back pain

Exercise of any kind may be uncomfortable initially, but will help to maintain the strength and function of your muscles. It is important to remember that your body is designed to move, not to lie still.

Exercises for low back pain may involve:

- Postural training.

- Abdominal muscle strengthening

- Reconditioning and increasing fitness with regular, low-stress aerobic exercise

Medications for lower back pain

Depending on the type of back pain you have, your doctor might recommend the following:

- Over-the-counter (OTC) anti-inflammatories. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin IB, others) or naproxen sodium (Aleve), may help relieve back pain. Take these medications only as directed by your doctor. Overuse can cause serious side effects. If OTC pain relievers don’t relieve your pain, your doctor might suggest prescription NSAIDs.

- Topical pain relievers. Topical pain relief such as creams, gels, patches, or sprays applied to the skin stimulate the nerves in the skin to provide feelings of warmth or cold in order to dull the sensation of pain. Common topical medications include capsaicin and lidocaine.

- Muscle relaxants. If mild to moderate back pain doesn’t improve with OTC pain relievers, your doctor might also prescribe a muscle relaxant. Muscle relaxants are prescription drugs that are used on a short-term basis to relax tight muscles. Muscle relaxants can make you dizzy and sleepy.

- Narcotics or opioids. Drugs containing opioids, such as oxycodone or hydrocodone, may be used for a short time with close supervision by your doctor. Opioids don’t work well for chronic pain, so your prescription will usually provide less than a week’s worth of pills.

- Antidepressants. Some types of antidepressants — particularly duloxetine (Cymbalta) and tricyclic antidepressants, such as amitriptyline — have been shown to relieve chronic back pain independent of their effect on depression.

- Anti-seizure medications.

It is reasonable that your doctor will put you on a trial of painkillers. The type of painkillers (acetaminophen, NSAIDs, opioids etc.) will depend on the severity of your pain and your doctor may change the strength of painkillers as your symptoms change. You may also be prescribed muscle relaxants to reduce spasm of muscle around the nerve. This has shown to work for some people. It is important to discuss the side effects of these medications, if any, with your doctor.

Physical therapy

Once your acute pain improves, a physical therapist can teach you exercises to increase your flexibility, strengthen your back and abdominal muscles, and improve your posture. Regular use of these techniques can help keep pain from returning. Physical therapists will also provide education about how to modify your movements during an episode of back pain to avoid flaring pain symptoms while continuing to be active.

Alternative medicine

Alternative therapies commonly used for low back pain include:

- Acupuncture. In acupuncture, the practitioner inserts hair-thin needles into your skin at specific points on your body. Some studies have suggested that acupuncture can help back pain, while others have found no benefit. If you decide to try acupuncture, choose a licensed practitioner to ensure that he or she has had extensive training.

- Chiropractic. Spinal adjustment (manipulation) is one form of therapy chiropractors use to treat restricted spinal mobility. The goal is to restore spinal movement and, as a result, improve function and decrease pain. Spinal manipulation appears to be as effective and safe as standard treatments for low back pain, but might not be appropriate for radiating pain.

- Behavioral approaches include:

- Biofeedback involves attaching electrodes to the skin and using an electromyography machine that allows people to become aware of and control their breathing, muscle tension, heart rate, and skin temperature; people regulate their response to pain by using relaxation techniques

- Cognitive therapy involves using relaxation and coping techniques to ease back pain

Steroid injections

If other measures don’t relieve your pain, and if your pain radiates down your leg, your doctor might recommend injection of a corticosteroid medication — plus a numbing medication into the space around your spinal cord (epidural space). Corticosteroids help reduce pain by suppressing inflammation around the irritated nerve. Studies have shown positive short-term effects for reducing pain in a proportion of people. But the pain relief usually lasts only a month or two, hence long-terms effects should not be expected. The number of steroid injections you can receive is limited because the risk of serious side effects increases when the injections occur too frequently.

Trigger point injections can relax knotted muscles (trigger points) that may contribute to back pain. An injection or series of injections of a local anesthetic and often a corticosteroid drug into the trigger point(s) can lessen or relieve pain.

Other procedures

- Radiofrequency neurotomy also called a rhizotomy. In this procedure, a fine needle is inserted through your skin so the tip is near the area causing your pain. Radio waves are passed through the needle to damage the nearby nerves, which interferes with the delivery of pain signals to the brain.

- Implanted nerve stimulators. Devices implanted under your skin can deliver electrical impulses to certain nerves to block pain signals.

- Spinal cord stimulation uses low-voltage electrical impulses from a small implanted device that is connected to a wire that runs along the spinal cord. The impulses are designed to block pain signals that are normally sent to the brain.

- Dorsal root ganglion stimulation also involves electrical signals sent along a wire connected to a small device that is implanted into the lower back. It specifically targets the nerve fibers that transmit pain signals. The impulses are designed to replace pain signals with a less painful numbing or tingling sensation.

- Peripheral nerve stimulation also uses a small implanted device and an electrode to generate and send electrical pulses that create a tingling sensation to provide pain relief.

- Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS). Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) therapy uses electrical current, delivered via electrodes placed on intact skin, to stimulate peripheral nerves. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) involves wearing a battery-powered device which places electrodes on the skin over the painful area that generate electrical impulses designed to block or modify the perception of pain. According to the gate-control theory, this stimulation activates inhibitory interneurons in the spinal cord, thereby interfering with the propagation of pain signals 22. A Cochrane review on the subject included four high-quality randomized controlled trials and concluded that TENS was not more effective than placebo for low back pain 23. Three studies addressed whether the use of TENS decreased the intensity of chronic low back pain, and found conflicting evidence of benefit. Two of the studies showed no statistically significant or clinically important improvements at their end points of two weeks and four weeks 24, 25. In the same Cochrane review, two studies addressed whether TENS improves functional status in patients with chronic low back pain using validated scales of disability. Both studies failed to demonstrate improvement in functional status 26, 27.

- Traction involves the use of weights and pulleys to apply constant or intermittent force to gradually “pull” the skeletal structure into better alignment. Some people experience pain relief while in traction but the back pain tends to return once the traction is released.

Surgery

If you have unrelenting pain associated with radiating leg pain or progressive muscle weakness caused by nerve compression, you might benefit from surgery. Surgery is usually reserved for pain related to structural problems, such as narrowing of the spine (spinal stenosis), a herniated disk, serious musculoskeletal injuries, or nerve compression that hasn’t responded to other therapy. This option is usually reserved for when the compressed nerve causes significant weakness, loss of bowel or bladder control, or when you have pain that progressively worsens or doesn’t improve with other therapies.

Specific surgeries are selected for specific conditions/indications. However, surgery is not always successful. It may be months following surgery before the person is fully healed and there may be permanent loss of flexibility.

Before you agree to back surgery, consider getting a second opinion from a qualified spine specialist. Spine surgeons may hold different opinions about when to operate, what type of surgery to perform and whether — for some spine conditions — surgery is warranted at all. Back and leg pain can be a complex issue that may require a team of health professionals to diagnose and treat.

Different types of back surgery include:

- Discectomy and microdiscectomy. This involves removal of the herniated portion of a disk through an incision in the back to relieve irritation and inflammation of a nerve. (Microdiscectomy uses a much smaller incision in the back and allows for a more rapid recovery). Diskectomy typically involves full or partial removal of the back portion of a vertebra (lamina) to access the ruptured disk. Laminectomy and discectomy are frequently performed together and the combination is one of the more common ways to remove pressure on a nerve root from a herniated disc or bone spur.

- Spinal laminectomy (also known as spinal decompression) is done when a narrowing of the spinal canal causes pain, numbness, or weakness. This procedure involves the removal of the bone overlying the spinal canal (the lamina or bony walls). It enlarges the spinal canal and is performed to relieve nerve pressure caused by spinal stenosis.

- Foraminotomy is an operation that “cleans out” or enlarges the bony hole (foramen) where a nerve root exits the spinal canal. Bulging discs or joints thickened with age can narrow the space where the spinal nerve exits and press on the nerve. Small pieces of bone over the nerve are removed through a small slit, allowing the surgeon to cut away the blockage and relieve pressure on the nerve.

- Nucleoplasty also called plasma disc decompression (PDD), is a type of laser surgery that uses radiofrequency energy to treat people with low back pain associated with mildly herniated discs. Under x-ray guidance, a needle is inserted into the disc. A plasma laser device is then inserted into the needle and the tip is heated to 40-70 degrees Celsius, creating a field that vaporizes the tissue in the disc, reducing its size and relieving pressure on the nerves.

- Spinal fusion. Spinal fusion permanently connects two or more bones in your spine. Spinal fusion is used to strengthen the spine and prevent painful movements in people with degenerative disc disease or spondylolisthesis (following laminectomy). It is occasionally used to eliminate painful motion between vertebrae that can result from a degenerated or injured disk. The spinal disc between two or more vertebrae is removed and the adjacent vertebrae are “fused” by bone grafts and/or metal devices secured by screws. Spinal fusion may result in some loss of flexibility in the spine and requires a long recovery period to allow the bone grafts to grow and fuse the vertebrae together. Spinal fusion has been associated with an acceleration of disc degeneration at adjacent levels of the spine.

- Artificial disc replacement. Implanted artificial disks are a treatment alternative to spinal fusion for painful movement between two vertebrae due to a degenerated or injured disk. The procedure involves removing the disc and replacing it with a synthetic disc that helps restore height and movement between the vertebrae. But these relatively new devices aren’t an option for most people.

- Interspinous spacers are small devices that are inserted into the spine to keep the spinal canal open and avoid pinching the nerves. It is used to treat people with spinal stenosis.

- Vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty for fractured vertebra are minimally invasive treatments to repair compression fractures of the vertebrae caused by osteoporosis. Vertebroplasty uses three-dimensional imaging to assist in guiding a fine needle through the skin into the vertebral body, the largest part of the vertebrae. A glue-like bone cement is then injected into the vertebral body space, which quickly hardens to stabilize and strengthen the bone and provide pain relief. In kyphoplasty, prior to injecting the bone cement, a special balloon is inserted and gently inflated to restore height to the vertebral structure and reduce spinal deformity.

Although approximately 1 million spinal surgeries are performed annually in the United States 28, high-quality, long-term data are lacking or equivocal for many of the procedures performed. The Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial, a randomized cohort study, compared the effect of surgical intervention with that of nonsurgical medical management for spinal stenosis, lumbar disk herniation, and spondylolisthesis 29, 30. Patients with lumbar disk herniation who received open discectomy or microdiscectomy did not differ statistically from the nonsurgical control group. Similarly, treatment outcomes for patients who underwent laminectomy with or without fusion for degenerative spondylolisthesis were similar to outcomes in the nonsurgical control group on intent-to-treat analysis. In contrast, patients with evidence of spinal stenosis and radicular leg pain who were assigned to decompressive laminectomy showed sustained improvement in bodily pain, physical function, and Oswestry Disability Index scores up to four years postsurgery 30. However, it is difficult to interpret these findings given the high frequency of crossover and variability in symptom severity. Minimally invasive spinal surgery appears to be a promising treatment modality, although rigorous studies have not been completed to date 31, 32. Patient education on realistic expectations of outcomes from a surgical referral for chronic low back pain is essential.

Rehabilitation programs

Rehabilitation teams use a mix of healthcare professionals from different specialties and disciplines to develop programs of care that help people live with chronic pain. The programs are designed to help the individual reduce pain and reliance on opioid pain medicines. Programs last usually two to three weeks and can be done on an in-patient or out-patient basis.

- Common Questions About Chronic Low Back Pain. Am Fam Physician. 2015 May 15;91(10):708-714. https://www.aafp.org/afp/2015/0515/p708.html[↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Global Burden of Disease Study 2013 Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2015;386(9995):743–800.[↩]

- Dagenais S, Caro J, Haldeman S. A systematic review of low back pain cost of illness studies in the United States and internationally. Spine J. 2008 Jan-Feb;8(1):8-20. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2007.10.005[↩]

- Vingård E, Mortimer M, Wiktorin C, Pernold R P T G, Fredriksson K, Németh G, Alfredsson L; Musculoskeletal Intervention Center-Norrtälje Study Group. Seeking care for low back pain in the general population: a two-year follow-up study: results from the MUSIC-Norrtälje Study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2002 Oct 1;27(19):2159-65. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200210010-00016[↩]

- Chiodo AE, Bhat SN, Van Harrison R, et al. Low Back Pain [Internet]. Ann Arbor (MI): Michigan Medicine University of Michigan; 2020 Nov. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK572334[↩]

- Low Back Pain Fact Sheet. https://www.ninds.nih.gov/disorders/patient-caregiver-education/fact-sheets/low-back-pain-fact-sheet[↩]

- Murray CJ, Vos T, Lozano R, Naghavi M, Flaxman AD, et al. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012 Dec 15;380(9859):2197-223. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61689-4. Erratum in: Lancet. 2013 Feb 23;381(9867):628.[↩]

- Roger Chou, Amir Qaseem, Vincenza Snow, et al. Diagnosis and Treatment of Low Back Pain: A Joint Clinical Practice Guideline from the American College of Physicians and the American Pain Society. Ann Intern Med.2007;147:478-491. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-147-7-200710020-00006[↩][↩]

- Downie, A., Williams, C. M., Henschke, N., Hancock, M. J., Ostelo, R. W., de Vet, H. C., Macaskill, P., Irwig, L., van Tulder, M. W., Koes, B. W., & Maher, C. G. (2013). Red flags to screen for malignancy and fracture in patients with low back pain: systematic review. BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 347, f7095. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.f7095[↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Williams CM, Henschke N, Maher CG, van Tulder MW, Koes BW, Macaskill P, Irwig L. Red flags to screen for vertebral fracture in patients presenting with low-back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013 Jan 31;(1):CD008643. https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD008643.pub2/full[↩]

- Henschke N, Maher CG, Ostelo RW, de Vet HC, Macaskill P, Irwig L. Red flags to screen for malignancy in patients with low-back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013 Feb 28;(2):CD008686. https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD008686.pub2/full[↩][↩][↩]

- Koes, B. W., van Tulder, M., Lin, C. W., Macedo, L. G., McAuley, J., & Maher, C. (2010). An updated overview of clinical guidelines for the management of non-specific low back pain in primary care. European spine journal : official publication of the European Spine Society, the European Spinal Deformity Society, and the European Section of the Cervical Spine Research Society, 19(12), 2075–2094. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-010-1502-y[↩]