Loxoscelism

Loxoscelism are the signs and symptoms observed following bites by brown spider of the genus Loxosceles 1. Since the brown spider, an arachnid of the genus Loxosceles (Araneae, Sicariidae), can be found worldwide, it has different common names depending on the region it is found, including brown recluse, violin spider and fiddleback spider 2. Characteristic violin-shaped markings on their backs have led brown recluse spiders to also be known as fiddleback spiders.

Loxosceles spiders have a worldwide distribution, their distribution is heavily concentrated in the Western Hemisphere, particularly the tropical urban regions of South America and are considered one of the most medically important groups of spiders 3. Loxosceles spiders envenomation (loxoscelism) can result in dermonecrosis and less commonly, a systemic illness that can be fatal 4. The mechanism of venom action is multifactorial and incompletely understood. The characteristic dermonecrotic lesion results from the direct effects of the venom on the cellular and basal membrane components, as well as the extracellular matrix. The initial interaction between the venom and tissues causes complement activation, migration of polymorphic neutrophils, liberation of proteolytic enzymes, cytokine and chemokine release, platelet aggregation, and blood flow alterations that result in edema and ischemia, with development of necrosis. There is no definitive treatment for loxoscelism. However, animal model studies suggest the potential value of specific antivenom to decrease lesion size and limit systemic illness even when such administration is delayed.

Of the 13 species of Loxosceles in the United States, at least five have been associated with necrotic arachnidism. Dermonecrotic arachnidism refers to the local skin and tissue injury that results from brown recluse spider envenomation. Loxoscelism is the term used to describe the systemic clinical syndrome caused by envenomation from the brown spiders 5. Loxosceles reclusa or the brown recluse spider, is the spider most commonly responsible for loxoscelism 6. In the United States, Loxosceles reclusa or brown recluse spiders are found mostly in the south, west, and midwest areas. The loxosceles spider or brown recluse spider, living up to its name, is naturally nonaggressive toward humans and prefers to live in undisturbed attics, woodpiles, and storage sheds. They are usually in dark areas such as under rocks, in the bark of dead trees, attics, basements, cupboards, drawers, boxes, bedsheets, or similar locations. Loxosceles spiders vary in size and can be up to 2-3 cm in total length. Loxosceles spiders are most active at night from spring to fall.

Loxosceles spider or brown spider venom is a complex mixture of toxins enriched in low molecular mass proteins (4–40 kDa). Characterization of the venom confirmed the presence of three highly expressed protein classes: sphingomyelinase D (phospholipases D), metalloproteases (astacins) and insecticidal peptides (knottins) 1. Recently, toxins with low levels of expression have also been found in Loxosceles venom, such as serine proteases, protease inhibitors (serpins), hyaluronidases, allergen-like toxins and histamine-releasing factors. The toxin belonging to the phospholipase-D family (also known as the dermonecrotic toxin) is the most studied class of brown spider toxins. This class of toxins single-handedly can induce inflammatory response, dermonecrosis, hemolysis, thrombocytopenia and renal failure. The functional role of the hyaluronidase toxin as a spreading factor in loxoscelism has also been demonstrated. However, the biological characterization of other toxins remains unclear and the mechanism by which Loxosceles toxins exert their noxious effects is yet to be fully elucidated.

Although Loxosceles spider bites are usually mild, they may ulcerate or cause more severe, systemic reactions. These injuries mostly are due to sphingomyelinase D in the spider venom. There is no proven effective therapy for Loxosceles bites, although many therapies are reported in the literature.

Figure 1. Loxosceles spider

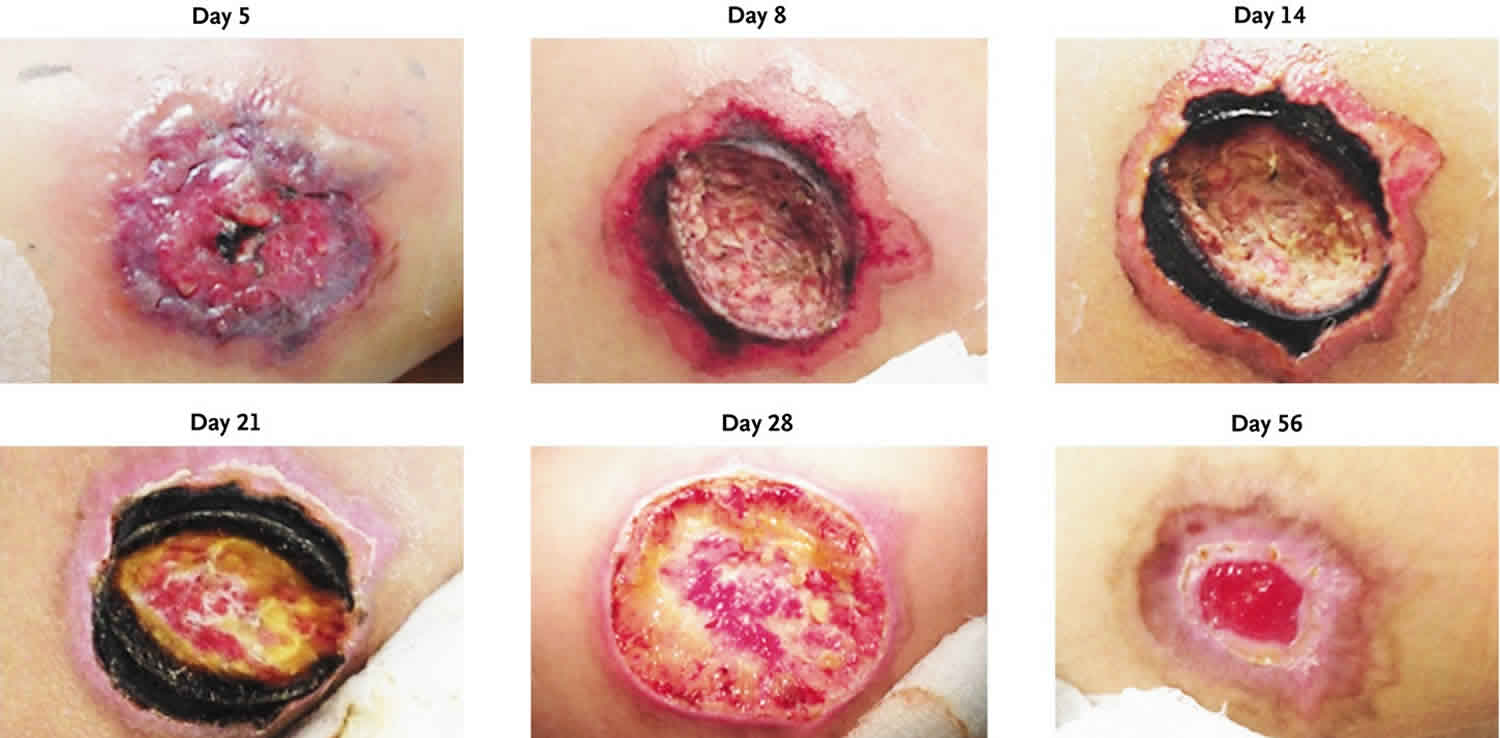

Figure 2. Cutaneous loxoscelism

Footnote: A 10-year-old healthy girl from a rural area in Northeast Mexico was bitten on the right posterior lateral thigh by a spider that had characteristics matching those of a brown recluse spider (Loxosceles reclusa). Five days later, a necrotic lesion with a diameter of 6.1 cm and perilesional edema developed in the area of the bite, accompanied by fever. The patient was treated with clindamycin, ceftazidime, acetaminophen, and ketorolac tromethamine. On day 8, débridement of the necrotic area was performed, with resolution of the fever and edema 12 hours later. On day 14, the patient was pain-free and was discharged; there was a necrotic border on the area of débridement. By day 21, the lesion was healing slowly and the necrotic border was unchanged. On day 28, a second débridement was performed because of the slow regeneration of tissue. By day 56, the wound was painless and almost healed, with initiation of scar formation.

[Source 7 ]Loxoscelism signs and symptoms

Brown recluse spider bites usually occur while indoors and as a defense mechanism as they are crushed or rolled over in bed. Envenomation from the brown recluse spider elicits minimal initial sensation and frequently goes unnoticed until several hours later when the pain intensifies. The bite site may initially have two small puncture wounds with surrounding erythema. From there, the center of the bite will become paler as the outer edge becomes red and edematous; this relates to vasospasm which will cause the pain to become more severe. Over the next few days, a blister will form, and the center of the ulcer will turn a blue/violet color with a hard, stellate, sunken center. After this step, skin sloughing can occur, and the wound will eventually heal by secondary intention, but this can take several weeks.

Some bites will present with only an urticarial rash. If the bite is more severe, the course usually is as follows. The initial bite will be painless, but over the subsequent two to eight hours it will become increasingly painful. Systemic symptoms of brown recluse venom can present as malaise, nausea, headache, and myalgias. In children, the systemic reaction is more severe and may also include weakness, fever, joint pain, hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia, organ failure, disseminated intravascular coagulation, seizures, and death.

Symptoms of systemic loxoscelism are not related to the extent of local tissue reaction and include the following 8:

- Morbilliform rash

- Fever

- Chills

- Nausea

- Vomiting

- Joint pain

- Hemolysis

- Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC)

- Renal failure

- Seizures

- Coma.

Loxoscelism diagnosis

Diagnosis of loxoscelism is difficult and usually presumptive. It is often made through evolution of the clinical picture and epidemiological information, since few patients bring the animal for its identification 9.

Loxosceles spider bite is a clinical diagnosis. A diagnosis of a spider bite can be made definitively only if the patient has a lesion that is consistent with a spider bite, or the spider was seen biting the patient, and the spider is caught and identified by an entomologist.

If the clinician makes a working diagnosis of a brown recluse spider bite, lab testing is unnecessary except if there are systemic complaints, especially in children 10. In these patients the following laboratory studies are performed;

- CBC

- Basic metabolic panel

- Serum calcium and phosphate

- Liver function test

- Creatine kinase/myoglobin

- Reticulocyte count

- Haptoglobin

- Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH)

- PT/ INR

- D Dimer

- Fibrinogen

Recently, an experimental study developed a recombinant immunotracer based on a monoclonal antibody that reacts with Loxosceles intermedia venom components of 32–35 kDa and neutralizes the dermonecrotic activity of the venom. This antibody was re-engineered into a colorimetric bifunctional protein (antibody fragment fused to alkaline phosphatase) that proved to be efficient in two stated immunoassays. This immunotracer could become a valuable tool to develop immunoassays that may facilitate a rapid and reliable diagnostic of loxoscelism 11. As the cases of loxoscelism became noteworthy, Loxosceles spider venoms started to be investigated and biologically and biochemically characterized.

Often a bite from a presumed arachnid can be mistaken as a bite from the brown recluse spider. Most patients aren’t able to find the spider. A helpful mnemonic to use is NOT RECLUSE 12, to help exclude the cause of bite from a brown recluse spider.

- N (numerous) – only one lesion is usually present in a brown recluse spider bite.

- O (occurrence) – A bite usually occurs when disturbing the spider. As the name suggests, they tend to avoid people, hiding in dark spaces like in a box or the attic.

- T (timing) – Most bites occur between April and October.

- R (red center) – characteristic bites will have a pale central area secondary to the capillary bed destruction causing ischemia.

- E (elevated) – Usually the bites are flat. If the area is elevated >1 cm, then this is most likely not a brown recluse spider bite.

- C (chronic) – bites from a brown recluse spider most commonly heal within 3 months.

- L (large) – Rarely are these bites >10 cm.

- U (Ulcerates too early) – If the bite is from a brown recluse spider, they do not ulcerate until 7-14 days.

- S (swollen) – often brown recluse spider bites do not exhibit significant swelling unless they occur on the face or the feet

- E (exudative) – brown recluse spider bites do not cause exudative lesions

Loxoscelism treatment

Initial treatment should begin with simple first aid. Elevate the extremity above the heart or at least in a neutral position. The activity of sphingomyelinase D is temperature dependent so an ice pack to the area should help halt the necrosis process 13. Clean the wound with soap and water and ensure the patient’s tetanus immunization is up to date. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) can provide pain management, but some people may need opioids. Antibiotics are only necessary if there is associated cellulitis.

The treatment for loxoscelism includes mainly antivenom, corticosteroids and dapsone 1. However, there are no clinical trials to substantiate any method plus there is scant evidence for the use of dapsone or antivenom 14. Also, note that dapsone is harmful in patients with G6PD deficiency 15 and can also cause deadly hypersensitivity reactions 16. Corticosteroids may be beneficial as they have been shown to decrease hemolysis and help prevent renal failure. If the infection is severe, consider hyperbaric oxygen therapy and surgical excision after the wound is well demarcated may be a consideration 17. Early surgical debridement is not advisable.

Indications for antivenom therapy depend mainly on the time of progression – the earlier the therapy is performed the greater the efficacy 1. This was corroborated by an experimental study that showed that necrotic injuries in rabbits were about 90% smaller compared with the control when the antivenom was administered up to 6 hours, while the reduction in the lesion dropped to 30% when the antivenom was administered up to 48 hours after the bite 18. Health protocols in Brazil, Peru and Argentina advise the use of intravenous antivenom in cases of cutaneous or cutaneous-hemolytic forms of loxoscelism – when hemolysis is present the antivenom is indicated even 48 hours after the bite 19.

However, antivenom therapy may lead to anaphylactic reactions. A clinical study showed that almost one third of the patients who received antivenom manifested some type of early anaphylactic reaction 9. Experimental studies demonstrate some efforts in this direction by developing alternative means to elicit a protective immune response against the noxious effects of dermonecrotic toxins, such as using an immunogenic synthetic peptide or a neutralizing monoclonal antibody that protect rabbits mainly against dermonecrotic toxin activity 20. In this context, another study deepened this issue when it identified peptide epitopes of representative toxins in three species of Loxosceles describing new antigenic regions important to induce neutralizing antibodies. These synthetic peptides where used to develop an in vitro method to evaluate the neutralizing potency of horse hyperimmune sera (anti-Loxosceles sera) 21.

Epitopes of a recombinant dermonecrotic toxin from Loxosceles intermedia venom were also used to construct a chimeric protein called rCpLi. In this study, the authors demonstrate that horses immunized with three initial doses of crude venom followed by nine doses of rCpLi generate antibodies with the same reactivity as those produced following immunization exclusively with whole venom. They argue that the use of this new generation of antivenoms will reduce the suffering of horses and devastation of arachnid fauna 22.

Management for systemic symptoms is different than for local effects; hospital admission is the recommendation for patients with hemolytic anemia, rhabdomyolysis, disseminated intravascular coagulation or end-stage organ failure. Treatment of these conditions is not different in this scenario than it would be for any other cause.

In children, systemic loxoscelism may preclude skin findings and should be considered as a differential in pediatric patients with undifferentiated acute hemolytic anemia especially in regions known to have the brown recluse spider. Hemolysis has been reported up to 7 days after spider bite so adequate follow up instructions should be given to parents of children even if there are no systemic findings during the emergency department visit 23. At a minimum, one should obtain a urinalysis at the initial visit if the working diagnosis is a brown recluse spider bite and the patient is being discharged.

Loxoscelism prognosis

Most cases of brown recluse Spider envenomation manifest only as local soft tissue destruction. Death is rare but has been reported especially in children 24.

Complications

After 4 to 6 weeks of therapy, it may be necessary to proceed with delayed skin grafting.

- Chaves-Moreira D, Senff-Ribeiro A, Wille ACM, Gremski LH, Chaim OM, Veiga SS. Highlights in the knowledge of brown spider toxins. J Venom Anim Toxins Incl Trop Dis. 2017;23:6. Published 2017 Feb 8. doi:10.1186/s40409-017-0097-8 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5299669[↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Lucas SM. The history of venomous spider identification, venom extraction methods and antivenom production: a long journey at the Butantan Institute, Sao Paulo, Brazil. J Venom Anim Toxins Incl Trop Dis. 2015;21:21. doi: 10.1186/s40409-015-0020-0[↩]

- Loxoscelism. Clinics in Dermatology Volume 24, Issue 3, May–June 2006, Pages 213-221 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clindermatol.2005.11.006[↩]

- Loxoscelism: Old obstacles, new directions. Annals of Emergency Medicine Volume 44, Issue 6, December 2004, Pages 608-624 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2004.08.028[↩]

- Chaves-Moreira D, Senff-Ribeiro A, Wille ACM, Gremski LH, Chaim OM, Veiga SS. Highlights in the knowledge of brown spider toxins. J Venom Anim Toxins Incl Trop Dis. 2017;23:6.[↩]

- Brown Recluse Spider Envenomation. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/772295-overview[↩]

- Cutaneous Loxoscelism. N Engl J Med 2013; 369:e6 https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMicm1212607[↩]

- Brown Recluse Spider Envenomation Clinical Presentation. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/772295-clinical[↩]

- Malaque CM, Santoro ML, Cardoso JL, Conde MR, Novaes CT, Risk JY, Franca FO, de Medeiros CR, Fan HW. Clinical picture and laboratorial evaluation in human loxoscelism. Toxicon. 2011;58:664–71. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2011.09.011[↩][↩]

- Bernstein B, Ehrlich F. Brown recluse spider bites. J Emerg Med. 1986;4(6):457-62.[↩]

- Jiacomini I, Silva SK, Aubrey N, Muzard J, Chavez-Olortegui C, De Moura J, Billiald P, Alvarenga LM. Immunodetection of the “brown” spider (Loxosceles intermedia) dermonecrotoxin with an scFv-alkaline phosphatase fusion protein. Immunol Lett. 2016;173:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2016.03.001[↩]

- Stoecker WV, Vetter RS, Dyer JA. NOT RECLUSE-A Mnemonic Device to Avoid False Diagnoses of Brown Recluse Spider Bites. JAMA Dermatol. 2017 May 01;153(5):377-378.[↩]

- Merchant ML, Hinton JF, Geren CR. Sphingomyelinase D activity of brown recluse spider (Loxosceles reclusa) venom as studied by 31P-NMR: effects on the time-course of sphingomyelin hydrolysis. Toxicon. 1998 Mar;36(3):537-45.[↩]

- Manríquez JJ, Silva S. [Cutaneous and visceral loxoscelism: a systematic review]. Rev Chilena Infectol. 2009 Oct;26(5):420-32.[↩]

- Belfield KD, Tichy EM. Review and drug therapy implications of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2018 Feb 01;75(3):97-104.[↩]

- Shukkoor AA, Thangavelu S, George NE, Priya S. Dapsone Hypersensitivity Syndrome (DHS): A Detrimental Effect of Dapsone? A Case Report. Curr Drug Saf. 2019;14(1):37-39.[↩]

- Hadanny A, Fishlev G, Bechor Y, Meir O, Efrati S. Nonhealing Wounds Caused by Brown Spider Bites: Application of Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2016 Dec;29(12):560-566.[↩]

- Pauli I, Minozzo JC, da Silva PH, Chaim OM, Veiga SS. Analysis of therapeutic benefits of antivenin at different time intervals after experimental envenomation in rabbits by venom of the brown spider (Loxosceles intermedia) Toxicon. 2009;53:660–71. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2009.01.033[↩]

- Malaque CMS, Chaim OM, Entres M, Barbaro KC. Loxosceles and loxoscelism: biology, venom, envenomation, and treatment. In: Gopalakrishnakone P, Corzo G, de Lima MH, Diego-García E, editors. Spider venoms. Dordrecht: Springer Nature; 2016. pp. 419–444.[↩]

- Dias-Lopes C, Felicori L, Rubrecht L, Cobo S, Molina L, Nguyen C, Galea P, Granier C, Molina F, Chavez-Olortegui C. Generation and molecular characterization of a monoclonal antibody reactive with conserved epitope in sphingomyelinases D from Loxosceles spider venoms. Vaccine. 2014;32:2086–92. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.02.012[↩]

- Ramada JS, Becker-Finco A, Minozzo JC, Felicori LF, Machado de Avila RA, Molina F, Nguyen C, de Moura J, Chavez-Olortegui C, Alvarenga LM. Synthetic peptides for in vitro evaluation of the neutralizing potency of Loxosceles antivenoms. Toxicon. 2013;73:47–55. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2013.07.007[↩]

- Figueiredo LF, Dias-Lopes C, Alvarenga LM, Mendes TM, Machado-de-Avila RA, McCormack J, Minozzo JC, Kalapothakis E, Chavez-Olortegui C. Innovative immunization protocols using chimeric recombinant protein for the production of polyspecific loxoscelic antivenom in horses. Toxicon. 2014;86:59–67. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2014.05.007[↩]

- Raza S, Shortridge JR, Kodali MK, Nistala P, Kale G, Doll DC. Severe haemolytic anaemia with erythrophagocytosis following the bite of a brown recluse spider. Br. J. Haematol. 2014 Oct;167(1):1.[↩]

- Rosen JL, Dumitru JK, Langley EW, Meade Olivier CA. Emergency department death from systemic loxoscelism. Ann Emerg Med. 2012 Oct;60(4):439-41.[↩]