Lupus vulgaris

Lupus vulgaris is the commonest chronic, progressive form of cutaneous tuberculosis in adults with moderate or high-degree of immunity 1. Tuberculosis is an infection caused by Mycobacteria, most commonly Mycobacterium tuberculosis. This infection most commonly involves the lungs. When it involves the skin, it is called cutaneous tuberculosis. Lupus vulgaris is the most common form of cutaneous tuberculosis in adults in the Indian subcontinent and South Africa 2. All age groups are equally affected, with females two to three times more commonly than males 3. Unlike pulmonary tuberculosis, lupus vulgaris or cutaneous tuberculosis is not common. Of all the patients that present with extra-pulmonary manifestations of tuberculosis, 1% to 2% suffer from cutaneous tuberculosis. Lupus vulgaris is more prevalent in parts of the world where infection with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is common, multidrug‐resistant pulmonary tuberculosis or where people are immunodeficient for other reasons 4.

Lupus vulgaris is a multifactorial disease, the source of infection can be either endogenous active tuberculosis foci such as glandular or pulmonary, which spreads through hematogenous or lymphatic route or an exogenous source that spreads by direct inoculation of tuberculosis bacilli into the skin 5.

Lupus vulgaris usually occurs singly on the face or neck, while in Indian children it is commonly reported on the legs and buttocks 6. The high incidence of lupus vulgaris on the legs in Indian children had been explained by the re-inoculation of tuberculosis bacilli through minor trauma or infection, especially during squatting 7. The lesions have varied presentation in the form of plaque, hypertrophic, atrophic, ulcerative, mutilation, vegetative or tumor patterns, while clinical variants like multicentric lesions, symmetrical and sporotrichoid patterns have been recorded 8. Atrophic scarring may be seen even without prior ulceration 9. Initial lesions start as a collection of reddish papules that coalesce to form plaques with serpiginous or verrucous borders with central clearing and atrophy 10. There are a few reports of association of lupus vulgaris (cutaneous tuberculosis) with skeletal tuberculosis 11. Spontaneous involution may occur, and new lesions may arise within old scars. Complete healing rarely occurs without therapy 3.

Diagnosing lupus vulgaris may be a formidable task. Various diagnostic methods, including culture, Ziehl–Neelsen staining and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) may be negative in lupus vulgaris, because of the scarcity of the bacilli within the lesional tissue 12. Culture is the gold standard for diagnosis of tuberculosis.

It is very important that people who have lupus vulgaris are treated, finish the medicine, and take the drugs exactly as prescribed. If they stop taking the drugs too soon, they can become sick again; if they do not take the drugs correctly, the Mycobacterium tuberculosis bacteria that are still alive may become resistant to those drugs. Mycobacterium tuberculosis that is resistant to drugs is harder and more expensive to treat.

Lupus vulgaris can be treated by taking several drugs for 6 to 9 months. There are 10 drugs currently approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treating tuberculosis. Of the approved drugs, the first-line anti-tuberculosis agents that form the core of treatment regimens are:

- isoniazid (INH)

- rifampin (RIF)

- ethambutol (EMB)

- pyrazinamide (PZA).

Occasionally surgical excision of localised cutaneous tuberculosis is recommended.

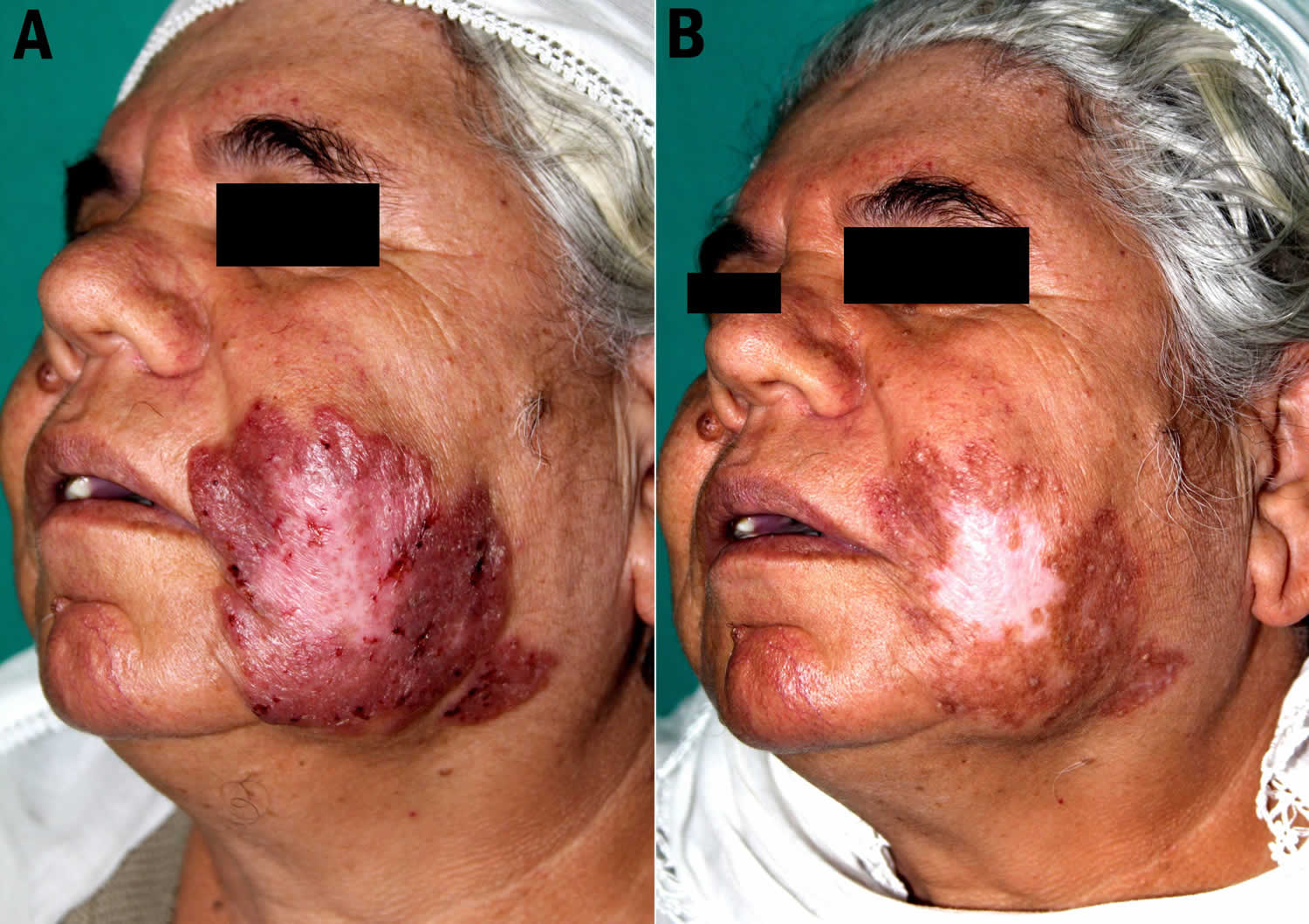

Figure 1. Lupus vulgaris cheek

Footnote: (A) Well-demarcated, large, reddish-brown plaque with an atrophic center located on the left cheek. (B) The lesion healed with hypopigmented, atrophic scarring at the end of the 6 months of treatment.

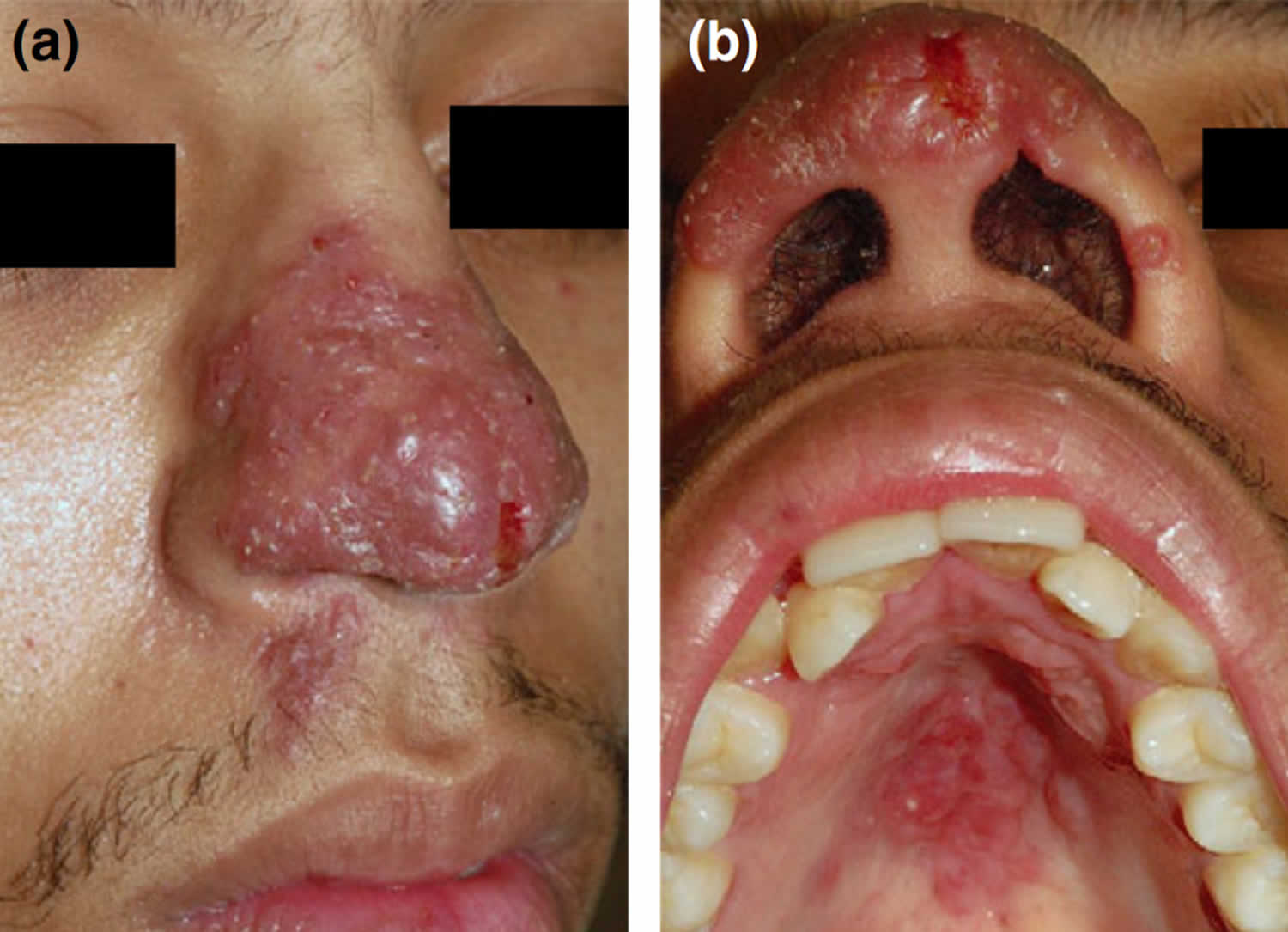

[Source 13 ]Figure 2. Lupus vulgaris nose

Footnote: (a) Confluent ‘apple jelly nodules’; (b) similar lesions on the hard palate.

[Source 14 ]Figure 3. Lupus vulgaris lesions on the right leg

[Source 8 ]Lupus vulgaris causes

Lupus vulgaris is generally regarded as a benign, chronic and progressive form of cutaneous tuberculosis that may be associated with tuberculosis of other organs. Infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis causes lupus vulgaris. Lupus vulgaris can also be caused by Mycobacterium bovis 15. It is a transmittable disease that spreads from one affected person to another. Lupus vulgaris usually originates from an endogenous source of tuberculosis due to spread of pulmonary tuberculosis and is spread hematogenously, lymphatically, or by contagious extension 16. Less commonly, it is acquired exogenously following primary inoculation tuberculosis or Bacillus Calmette–Guerin vaccine (BCG) vaccination 17.

Lupus vulgaris differential diagnosis

Lupus vulgaris differential diagnosis includes:

- Chronic vegetative pyoderma

- Blastomycosis

- Chromoblastomycosis

- Drug reactions

- Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener granulomatosis)

- Granulomatous rosacea

- Syphilitic gumma

- Keratosis spinulosa

- Papular eczema

- Coccidioidomycosis

- Glossitis

- Atypical mycobacterial infection

- Chronic granulomatous disease

- Lupoid rosacea

- Nodular vasculitis (Weber-Christian disease)

- Nodular pernio

Many different diseases can be included in differential diagnosis depending on the presentation of cutaneous tuberculosis. It is difficult to make a diagnosis of lupus vulgaris because of its resemblance with many other cutaneous lesions.

Lupus vulgaris prevention

Prevention of cutaneous tuberculosis involves BCG vaccination; identification, separation, and treatment of the person who is a source of infection; and use of sterilized instruments, along with other steps. As immunodeficiency is the biggest cause of skin tuberculosis, one should try to avoid it by controlling diabetes and other diseases. In cases where drug therapy is the cause of immunodeficiency, pretesting and treating latent tuberculosis with antibiotics are indicated.

Lupus vulgaris symptoms

Lupus vulgaris is characterized by a macule or papule, with a brownish-red color and soft consistency that form larger plaques by peripheral enlargement and coalescence 18. The characteristic morphological patterns are papular, plaque, nodular, tumid, atrophic and ulcerative forms. Atypical clinical forms such as cellulitis, lichen simplex chronicus, sporotrichoid, frambesiform, lichenoid, gangrenous, ulcero-vegetant and tumor-like have also been rarely encountered 19.

The lesions of lupus vulgaris are usually located on the head and neck area 20. Lupus vulgaris is rarely seen on arms and legs; those located on the extremities usually occur by reinoculation 18.

Lupus vulgaris diagnosis

Evaluation of suspected cutaneous tuberculosis requires history and examination along with a full workup. The workup may include chest radiograph, the tuberculosis skin test (TST) or Mantoux test, serum QuantiFERON-TB Gold (QFT-G) levels, PCR, and skin biopsy 21. The gold standard for establishing the diagnosis is culture of tubercular bacilli.

Tuberculosis skin test (TST) involves inoculation with 0.1 mL of liquid that contains purified protein derivative (PPD) into the skin. The site for the injection is the superficial skin of the volar wrist or forearm. The test is interpreted after a wait of 48 to 72 hours. The diameter of the skin induration is measured and recorded.

The serum serum QuantiFERON-TB Gold test is an alternative to tuberculin skin test (TST). It is a blood test that detects both active and latent tuberculosis by gamma interferon release assay.

Skin biopsy is a reliable test for the diagnosis of cutaneous tuberculosis. A skin biopsy is evaluated in 2 ways. First, slides are prepared and examined under a microscope to detect acid-fast bacilli. Second, the skin tissue is cultured at low temperature to detect growth of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Culture is the gold standard for diagnosis of tuberculosis.

Other tests that can help with diagnosis include a chest x-ray and sputum examination. Sputum examination involves microscopy for acid-fast bacilli (AFB) and culture.

Histopathology

The most prominent histopathologic feature is the formation of typical tubercles with or without caseation, surrounded by epitheliod histiocytes and multinucleate giant cells in the superficial epidermis with prominent peripheral lymphocytes 22. Secondary changes like epidermal thinning and atrophy or acanthosis with excessive hyperkeratosis or pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia can also be noted. Acid-fast bacilli are usually not found 3.

Lupus vulgaris treatment

Treatment of cutaneous tuberculosis is the same as treatment of systemic tuberculosis. It also involves multidrug treatment. The drugs that are most commonly used are isoniazid, rifampicin, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol or streptomycin. Regimens for treating tuberculosis disease consists of 2 phases, with an intensive phase of 2 months, followed by a continuation phase of either 4 or 7 months (total of 6 to 9 months for treatment).

- An intensive phase that involves rapidly decreasing the burden of M. tuberculosis

- A continuation phase that is also called the sterilizing phase

The intensive phase of therapy lasts about 8 weeks. After this phase, the patient no longer remains infectious, but he or she still requires more treatment to eradicate the infection. The continuation phase is designed to eradicate remaining bacteria and lasts for 9 to 12 months. Cure of tuberculosis requires the patient to adhere to treatment strictly.

Results of treatment depend on the immunity of a patient, their overall health, the stage of the disease, the type of cutaneous lesions, the patient’s compliance, duration of treatment, and any side effects experienced 23.

Compliance with treatment recommendations is essential when it comes to treating tuberculosis. A patient who is not compliant may cause the organisms to be drug resistant. Multiple therapies may be needed, and in such patients, directly observed treatment (DOT) is recommended.

Occasionally surgical excision of localized cutaneous tuberculosis is recommended.

Table 1. Drug susceptible tuberculosis disease treatment regimens

Footnotes: Use of once-weekly therapy with Isoniazid 900 mg and rifapentine 600 mg in the continuation phase is not generally recommended. In uncommon situations where more than once-weekly Directly Observed Therapy is difficult to achieve, once-weekly continuation phase therapy with Isoniazid 900 mg plus rifapentine 600 mg may be considered for use only in HIV uninfected persons without cavitation on chest radiography.

- a. Other combinations may be appropriate in certain circumstances; additional details are provided in the Official American Thoracic Society/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/Infectious Diseases Society of America Clinical Practice Guidelines: Treatment of Drug-Susceptible Tuberculosisexternal icon.

- b. When Directly Observed Therapy is used, drugs may be given 5 days per week and the necessary number of doses adjusted accordingly. Although there are no studies that compare 5 with 7 daily doses, extensive experience indicates this would be an effective practice. Directly Observed Therapy should be used when drugs are administered less than 7 days per week.

- c. Based on expert opinion, patients with cavitation on initial chest radiograph and positive cultures at completion of 2 months of therapy should receive a 7-month (31-week) continuation phase.

- d. Pyridoxine (vitamin B6), 25–50 mg/day, is given with Isoniazid to all persons at risk of neuropathy (e.g., pregnant women; breastfeeding infants; persons with HIV; patients with diabetes, alcoholism, malnutrition, or chronic renal failure; or patients with advanced age). For patients with peripheral neuropathy, experts recommend increasing pyridoxine dose to 100 mg/day.

- e. Alternatively, some U.S. TB control programs have administered intensive-phase regimens 5 days per week for 15 doses (3 weeks), then twice weekly for 12 doses.

Continuation Phase of Treatment

The continuation phase of treatment is given for either 4 or 7 months. The 4-month continuation phase should be used in most patients. The 7-month continuation phase is recommended only for the following groups:

- Patients with cavitary pulmonary tuberculosis caused by drug-susceptible organisms and whose sputum culture obtained at the time of completion of 2 months of treatment is positive;

- Patients whose intensive phase of treatment did not include Pyrazinamide;

- Patients with HIV who are not receiving antiretroviral treatment (ART) during tuberculosis treatment; and

- Patients being treated with once weekly Isoniazid and rifapentine and whose sputum culture obtained at the time of completion of the intensive phase is positive.

- (Note: Use of once-weekly therapy with Isoniazid 900 mg and rifapentine 600 mg in the continuation phase is not generally recommended. In uncommon situations where more than once-weekly DOT is difficult to achieve, once-weekly continuation phase therapy with Isoniazid 900 mg plus rifapentine 600 mg may be considered for use only in HIV uninfected persons without cavitation on chest radiography.)

Lupus vulgaris prognosis

Prognosis of lupus vulgaris is good in patients who are not immunocompromised. However, even aggressive treatment may not be effective in patients who are immunocompromised and where the organisms are multidrug resistant.

- Kumar B, Muralidhar S. Cutaneous tuberculosis: a twenty-year prospective study. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 1999 Jun;3(6):494-500.[↩]

- Bhutto AM, Solangi A, Khaskhely NM, Arakaki H, Nonaka S. Clinical and epidemiological observations of cutaneous tuberculosis in Larkana, Pakistan. Int J Dermatol. 2002 Mar;41(3):159-65. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2002.01440.x[↩]

- Tappeiner G. Tuberculosis and infections with atypical mycobacteria. In: Wolff K, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrist BA, Paller AS, Leffell DJ, editors. Fitzpatricks Dermatology in General Medicine. 7th ed. New York: McGraw Hill; 2008. pp. 1771–2.[↩][↩][↩]

- Wozniacka, A., Schwartz, R.A., Sysa‐Jedrzejowska, A., Borun, M. and Arkuszewska, C. (2005), Lupus vulgaris: report of two cases. International Journal of Dermatology, 44: 299-301. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-4632.2005.01976.x[↩]

- Sehgal VN, Srivastava G, Bajaj P, Sengal R. Re-infection (secondary) inoculation cutaneous tuberculosis. Int J Dermatol. 2001 Mar;40(3):205-9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2001.01138-6.x[↩]

- Sethuraman G, Ramesh V, Ramam M, Sharma VK. Skin tuberculosis in children: learning from India. Dermatol Clin. 2008 Apr;26(2):285-94, vii. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2007.11.006[↩]

- Padmavathy L, Rao LL. Ulcerative lupus vulgaris. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2005 Mar-Apr;71(2):134-5. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.14007[↩]

- Murugan S, Vetrichevvel T, Subramanyam S, Subramanian A. Childhood multicentric lupus vulgaris. Indian J Dermatol. 2011;56(3):343-344. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.82510 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3132924[↩][↩]

- Tappeiner G. Tuberculosis and infections with other atypical mycobacterial infections. In: Wolff K, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, Paller AS, Leffell DJ, editors. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 7th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Company; 2008. pp. 1768–75.[↩]

- Franco-Paredes C, Marcos LA, Henao-Martínez AF, et al. Cutaneous Mycobacterial Infections. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2018;32(1):e00069-18. Published 2018 Nov 14. doi:10.1128/CMR.00069-18[↩]

- Bhaskar, Khonglah T, Bareh J. Tuberculous dactylitis (spina ventosa) with concomitant ipsilateral axillary scrofuloderma in an immunocompetent child: A rare presentation of skeletal tuberculosis. Adv Biomed Res. 2013;2:29. Published 2013 Mar 6. doi:10.4103/2277-9175.107993[↩]

- Aliağaoğlu C, Atasoy M, Güleç AI. Lupus vulgaris: 30 years of experience from eastern Turkey. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:e289. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2009.03213.x[↩]

- Turan, E., Yurt, N., Yesilova, Y., & Celik, O. I. (2012). Lupus vulgaris diagnosed after 37 years: A case of delayed diagnosis. Dermatology Online Journal, 18(5). Retrieved from https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9k34f7gx[↩]

- Nico, M & Gavioli, Camila & Dabronzo, M & Romiti, R & Takahashi, M & Lourenço, Silvia. (2017). The many faces of tuberculosis of the oral mucosa- Three cases with distinct pathomechanisms. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. 32. 10.1111/jdv.14760[↩]

- Hirt P, Price A, Alwunais K, Schachner L. An interesting case of coincidental epidermolytic hyperkeratosis and erythema annulare centrifugum in the setting of latent tuberculosis in a 12-year-old female. Int J Dermatol. 2019 Nov;58(11):1337-1340. doi: 10.1111/ijd.14339[↩]

- Barbagallo J, Tager P, Ingleton R, Hirsch RJ, Weinberg JM. Cutaneous tuberculusis, diagnosis and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2002;3:319–28. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200203050-00004[↩]

- Pace Spadaro E, Xuereb Dingli J, Doffinger R, et al. BCG induced lupus vulgaris: an unexpected adverse event. Archives of Disease in Childhood 2018;103:71-72. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2016-312338[↩]

- Bravo FG, Gotuzzo E. Cutaneous tuberculosis. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:173–80. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2006.05.005[↩][↩]

- Goyal T, Varshney A, Bakshi SK. Lupus vulgaris in a young girl. Ann Saudi Med. 2013;33(4):404-406. doi:10.5144/0256-4947.2013.404 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6078518[↩]

- Thomas S, Suhas S, Pai KM, Raghu AR. Lupus vulgaris-report of a case with facial involvement. Br Dent J. 2005;198:135–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4812038[↩]

- Franco-Paredes C, Marcos LA, Henao-Martínez AF, Rodríguez-Morales AJ, Villamil-Gómez WE, Gotuzzo E, Bonifaz A. Cutaneous Mycobacterial Infections. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2018 Nov 14;32(1):e00069-18. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00069-18[↩]

- Yates VM. Mycobacterial infection. In: Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, Griffiths C, editors. Rook’s Textbook of Dermatology. 8th ed. Oxford: Blackwell Science Ltd; 2010. p. 31. (16-9).[↩]

- van Zyl L, du Plessis J, Viljoen J. Cutaneous tuberculosis overview and current treatment regimens. Tuberculosis (Edinb). 2015 Dec;95(6):629-638. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2014.12.006[↩]