What is manual lymphatic drainage

Manual lymphatic drainage massage also known as manual lymphatic drainage (MLD), is a gentle but very specific type of skin stretching massage that improves the transport of fluid and waste in your body through the lymphatic system. Manual lymphatic drainage massage helps blocked lymphatic fluid out of the swollen limb to drain properly into the bloodstream and may reduce swelling. However, manual lymphatic drainage (MLD) should not be confused with a traditional massage you may receive at a spa. Manual lymphatic drainage massage is specifically focused on the lymph vessels to help the flow of lymphatic fluid. Therapy is applied to your unaffected areas first, making it possible for the lymphatic fluid to move out of the affected area or “decongest” the region. Manual lymphatic drainage helps open the remaining functioning lymph collectors and move protein and fluid into them, as well as to help speed up lymph fluid flow through the lymphatics. For best results, you should begin manual lymphatic drainage massage as close to the start of lymphedema symptoms as possible. A member of your health care team can refer you to a certified lymphedema therapist trained in this technique. Manual lymphatic drainage massage was developed by Danish physiotherapist Dr. Emil Vodder and his wife, Estrid, in 1932 in Paris for treatment of swollen lymph nodes 1. According to Dr Vodder each manual lymphatic drainage treatment commences at the neck to clear the area and ‘make space’ for lymph to be brought there. The next parts of the sequence will depend entirely on why manual lymphatic drainage is being performed and the particular needs of the individual. However, lymph follows pre-determined pathways on its journey to the thoracic ducts (situated under the collarbone) and is continuous – if space is made at the top of the chain, fluid from lower down can ‘move up’. The lymphatic system does not have its own pump (unlike the circulation which has the heart) and relies on movement of muscles in the surrounding area to activate the collection of lymph from surrounding tissues.

The lymphatic system drains excess fluid and waste products from the tissues, deals with inflammation and infection, and transports fats and proteins around the body. If excess lymphatic fluid is present it can interfere with cell nutrition – oxygen and nutrients will take longer to pass through the tissues and get from the bloodstream to the cells through the interstitial fluid. This will also mean that waste products from cell metabolism will take longer to move from cells to the transport system, which will remove them from the body. The vessels of the lymphatic system progress through the body passing through clearing stations called lymph nodes or glands. You have between 600 and 800 lymph nodes (around 200 alone are thought to be in the area of the head and neck). They are arranged in clusters and chains, but each person’s exact arrangement is unique. Lymph nodes filter the lymph fluid then re-join the circulatory system before going to the kidneys that filter and process the blood, and excrete the waste products as urine. Lymph fluid usually flows at a rate of 10-12 bpm. Unlike the cardiac system, the lymphatic system does not have a pump, it relies on muscle movement, manual lymph drainage, or hydrostatic pressure. A manual lymphatic drainage therapist uses light and rhythmic hand movements on the skin, stimulating lymph nodes and the numerous lymphatic channels. Usually manual lymphatic drainage also incorporates breathing movements. Deep breathing techniques call diaphragmatic breathing are usually done at the beginning and end of a manual lymphatic drainage therapy session to help open your deep lymphatic pathways. It’s not only relaxing, but it helps increase movement of fluid toward your heart. Laughing naturally causes diaphragmatic breathing, so go ahead; laugh as often as you can! It’ll help move your lymphatic fluid and can help release stress, anxiety, and even depression. Following an hour long lymphatic massage, the lymphatic system flow rate will be approximately 100 to 120 bpm, and will gradually slow over the proceeding 48 hours.

It often takes many hours of training in manual lymphatic drainage, combined with years of hands-on experience, for a lymphedema therapist to become truly skilled.

To find a certified lymphedema therapist contact:

- Lymphology Association of North America (https://www.clt-lana.org)

- National Lymphedema Network (https://lymphnet.org)

A certified lymphedema therapist can help you with skin care, massage, special bandaging, exercises, and fitting for a compression garment. This treatment is called complete decongestive therapy (CDT). Components of complete decongestive therapy (CDT) include:

- Manual lymphatic drainage (MLD)

- Skin care

- Self-massage following instructions from their therapists

- Special light exercises designed to encourage the flow of lymphatic fluid out of the affected limb.

- Wear compression garments such as long sleeves or stockings designed to compress the arm or leg and encourage lymphatic flow out of the limb.

Complete decongestive therapy (CDT) is the most effective treatment for lymphedema, as it reduces the symptoms of lymphedema and improves patients’ functionality, mobility, and quality of life. It can achieve a 45-70% reduction in lymphedema volume. Manual lymphatic drainage (MLD) is the type of massage used as part of complete decongestive therapy (CDT) to decrease lymphedema. Daily complete decongestive therapy is used to reduce fluid volume as much as possible. This may take a few weeks. When the lymphedema is controlled as much as possible, a compression garment is used.

Although most insurance companies will pay for lymphedema treatment, some don’t cover the cost of compression garments and dressings. Check with your health insurance company to see what’s covered.

What is the lymphatic system?

The lymphatic system is part of your body’s circulatory and immune systems. It works alongside the blood system to keep your body healthy.

The lymphatic system main functions are to:

- Keep a healthy balance of fluid in the tissues

- Transport proteins and digested fats to provide your cells with nutrients

- Help fight infection by removing bacteria, viruses and other germs

The lymphatic system is your body’s sewer system

- It absorbs excess interstitial fluid, hormones, and cellular waste.

- It breaks down proteins and other cellular debris that are too big for the cardiac system to break down.

- Lymph fluid is a clear liquid made up of proteins, fats, salts, glucose, water, cellular debris, and white blood cells that fight infection

- Lymph vessels transport and drain lymph fluid back to the blood system and the heart

- Lymph nodes filter out bacteria, viruses, other germs and waste, to keep you healthy. Lymph nodes contain lymphocytes and phagocytes to break down those proteins, pathogens and other cellular waste.

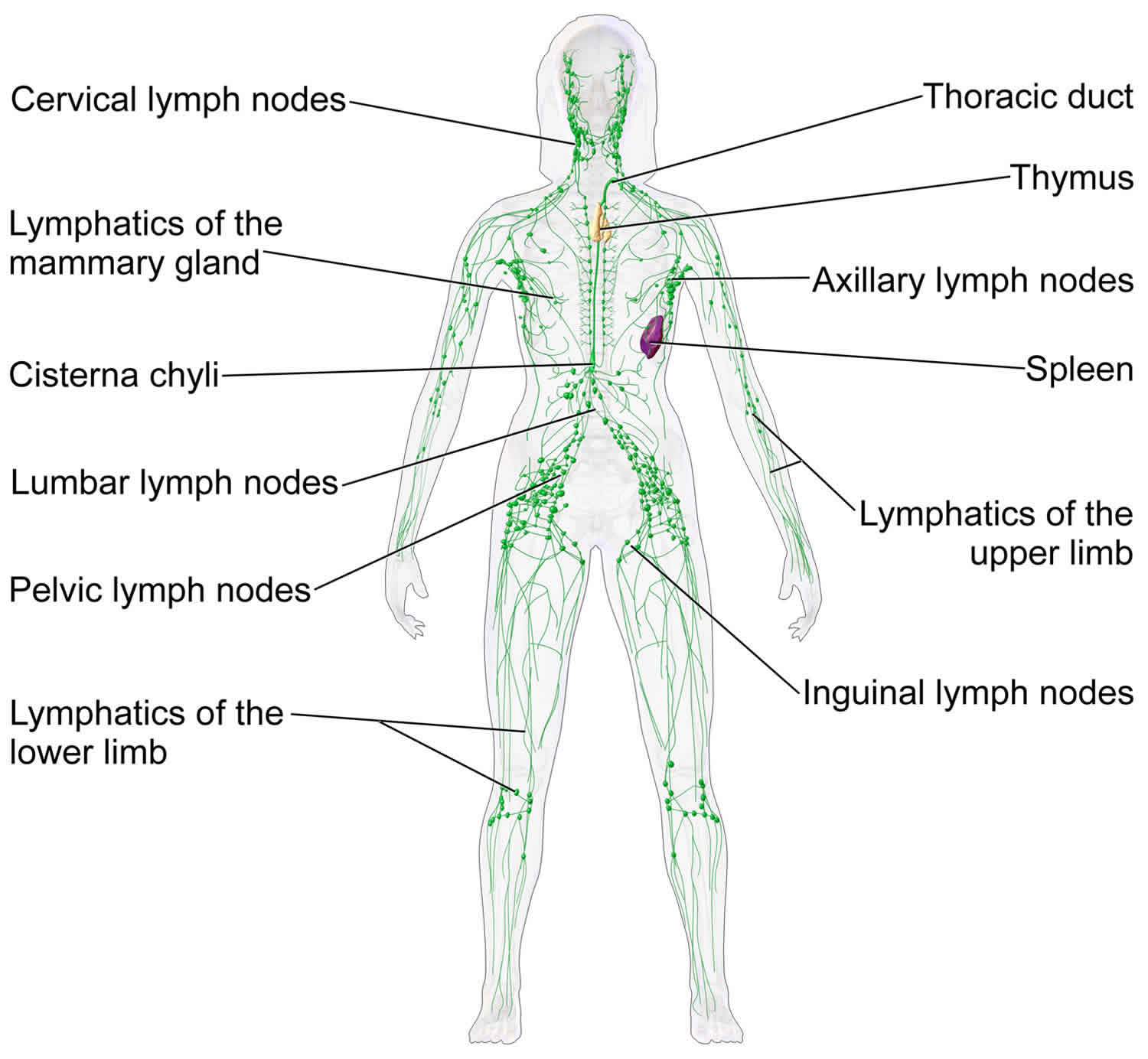

- There are hundreds of lymph nodes in your body. You have clusters of them in your neck, head, armpits, stomach and groin (see Figure 1). When you’re fighting an infection, you may feel the lymph nodes swell up in your neck, just below your jawbone. The exact number, size and location of lymph nodes vary from person to person. This may be why one person develops lymphedema and another doesn’t, even if they both have similar risk factors.

- “Clean” lymph fluid is transported back through lymph ducts to the veins.

- Once lymph fluid is in your veins it’s called plasma.

The lymphatic system moves lymph fluid towards the heart through a network of lymph vessels and lymph nodes. Lymph fluid usually flows at a rate of 10-12 bpm. Unlike the cardiac system, the lymphatic system does not have a pump, it relies on muscle movement, manual lymph drainage, or hydrostatic pressure. Following an hour long lymphatic massage, the lymphatic system flow rate will be approximately 100 to 120 bpm, and will gradually slow over the proceeding 48 hours.

Things that will slow the lymphatic system:

- Fighting off an infection, bacterial or viral.

- Primary and secondary lymphedema

- Surgery

- Traumatic event

- Pregnancy

- Lifestyle

- Sedentary vs active

- Lymphatic system relies on muscle movement for lymph flow. The less muscle movement, the slower the system.

- Sitting for long stretches of time causes muscle stiffness, and impedes the thoracic duct.

- Standing in one place for long periods of time will cause fluid to pool in the lower extremities.

- Diet

- High in sugar

- High in protein

- High in fat

- Heavy coffee drinkers (caffeine are broken down by lymph system)

- Dehydration – not providing the body with enough fluid

- Sedentary vs active

Sluggish lymph system results in:

- Edema

- Just like when a septic system gets clogged, the fluid has no where to go and ends up building up, just hanging around waiting. Sitting upon muscles and nerves, causing stiffness and pain.

- Adhesions and scar tissue

- Eventually this protein rich fluid begins to harden creating adhesions and fibrotic tissue within and around organs and muscles. Creating pain, dysfunction, and restricted range of motion.

- Illness

- Flow is stagnating so its not getting through the lymph nodes where the pathogens would be taken care of, allowing them to get into the surrounding cells. Literally breeding disease.

- Protein rich fluid that is turning rancid will cause inflammation.

Figure 1. Lymphatic system

What helps lymph flow?

Whereas blood is pumped around the body by the heart, lymph fluid moves in a different way. It moves slowly, in only one direction, through valves in the lymph vessels. Rather than being pushed along by a big pump like the heart, what helps lymph flow is:

- Moving your muscles

- Deep breathing

- A special kind of gentle massage called manual lymphatic drainage or manual lymphatic drainage massage

What restricts lymph flow?

Lymph flow is restricted by your body’s natural bottlenecks, where it bends at your knee, ankle, armpit, elbow or groin. It is also restricted by tissue injury, where you have bruising, swelling or scarring.

You can’t change your body, but you can change your habits. To help your lymph flow, try to avoid:

- Sitting or standing for long periods

- Sitting cross-legged

- Being inactive

- Wearing clothing with heavy elastic (that leaves a mark) at your waist, ankles, wrists or another part of your body

- Carrying excess weight at your girth

What is lymphedema?

Lymphedema is the abnormal buildup of fluid in soft tissue due to a blockage in the lymphatic system. Your lymphatic system helps fight infection and other diseases by carrying lymph throughout your body. Lymph may also be called lymphatic fluid is a colorless fluid containing white blood cells. Lymph travels through your body using a network of thin tubes called vessels. Small glands called lymph nodes filter bacteria and other harmful substances out of this fluid. But when the lymph nodes are removed or damaged, lymphatic fluid collects in the surrounding tissues and makes them swell.

Lymphedema may develop immediately after surgery or radiation therapy. Or, it may occur months or even years after cancer treatment has ended. Lymphedema that is related to cancer is most commonly caused by lymph node removal during surgery for cancer, or by the tumor itself which might block part of the lymph system. Increased white blood cells due to leukemia or an infection can also restrict lymph flow and cause lymphedema.

Most often, lymphedema affects the arms and legs. But it can also happen in the neck, face, mouth, abdomen, groin, or other parts of the body.

Lymphedema can occur in people with many types of cancers, including:

- Bladder cancer

- Breast cancer

- Head and neck cancer

- Melanoma

- Ovarian cancer

- Penile cancer

- Prostate cancer.

Stages of lymphedema

Doctors describe lymphedema according to its stage, from mild to severe:

- Stage 0. Swelling usually cannot be seen yet even though the lymphatic system has already been damages. Some people may feel heaviness or aching in the affected body part. This stage may last months or even years before swelling occurs.

- Stage 1. Swelling is visible but can be reduced by keeping the affected limb raised and using compression. The skin may indent when it is pressed, and there are no visible signs of skin thickening and scarring.

- Stage 2. The skin may or may not indent when it is pressed, but there is moderate to severe skin thickening. Compression and keeping the affected limb raised may help a little but will not reduce swelling.

- Stage 3. The skin has become very thick and hardened. The affected body part has swollen in size and volume, and the skin has changed texture, hyperpigmentation, increased skin folds, fat deposits and warty overgrowth develop. Stage 3 lymphedema is permanent.

Acute or temporary lymphedema

Lymphedema can start soon after surgery for cancer. This can be called acute or temporary (or short-term) lymphedema. It usually starts within days, weeks, or a few months (up to a year) after surgery, is usually mild, and goes away on its own or with some mild treatments

Even though this type of lymphedema usually goes away on its own over time, you should tell your doctor about it right away. The swollen area may look red and feel hot, which could be a sign of a blood clot, infection, or other problem that needs to be checked and treated.

If there are no other problems causing the swelling, temporary lymphedema might be treated by raising the arm or leg, doing light exercises, and possibly taking medicines prescribed by your doctor to help reduce the swelling (also called inflammation).

Chronic lymphedema

This form of lymphedema develops over time. It may show up a year or more after cancer treatment. The swelling can range from mild to severe. The lymph fluid that collects in the skin and underlying tissues can be very uncomfortable. It can keep nutrients from reaching the cells, interfere with wound healing, and lead to infections.

Lymphedema can be a long-term problem, but there are ways to manage it. The key is to know what to look for, and then to get help right away when you first notice signs and symptoms. Lymphedema is easier to treat and more likely to respond to treatment if it’s recognized and treated early.

What causes of lymphedema?

There are 2 main types of lymphedema:

- Primary lymphedema – caused by faulty genes that affect the development of the lymphatic system; it can develop at any age, but usually starts during infancy, adolescence, or early adulthood. At birth, about one person in every 6000 will develop primary lymphedema.

- Secondary lymphedema – caused by damage to the lymphatic system or problems with the movement and drainage of fluid in the lymphatic system; it can be the result of a cancer treatment, an infection, injury, inflammation of the limb, or a lack of limb movement

- Primary and secondary lymphedema can occur together.

Primary lymphedema in comparison to secondary lymphedema is the result of a congenital (present at birth) condition that affects how the lymph vessels where formed. This may result in hypoplasia of lymphatic vessels (a reduced number of lymphatic vessels), hyperplasia of lymphatic vessels (vessels that are too large to be functional) or aplasia (absence) of some part of the lymphatic system. This form may be presents at birth (congenital), develop at the onset of puberty (lymphedema precox) or not become apparent for many years into adulthood (lymphedema tarda). It may be associated with other congenital abnormalities/syndromes.

Lymphedema can be a long-term side effect of some cancer treatments. The most common causes of lymphedema in cancer survivors include:

- Surgery in which lymph nodes were removed. For example, surgery for breast cancer often involves removing 1 or more lymph nodes under the arm to check for cancer. This can cause lymphedema in the arm.

- Radiation therapy or other causes of inflammation or scarring in the lymph nodes and lymph vessels

- Blockage of the lymph nodes and/or lymph vessels by the cancer

The risk of lymphedema increases with the number of lymph nodes and lymph vessels removed or damaged during cancer treatment or biopsies. The incidence of secondary lymphedema associated with vulval cancer is estimated at 36-47%, breast cancer 20%, cervical cancer 24% and melanoma 9-29%. The incidence of lymphedema following sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) is reported to range from 4-8%.

Sometimes lymphedema is not related to cancer or its treatment. For instance, a bacterial or fungal infection or another disease involving the lymphatic system may cause this problem. Secondary lymphedema may also arise without a cancer diagnosis when one or more of the following conditions occur:

- Trauma and tissue damage

- Venous disease

- Immobility and dependency

- Factious – self harm

- Infection such as cellulitis

- Filariasis – Lymphatic filariasis is a major cause of lymphedema in the sub-tropical areas of the world. Parasitic filarial worms are transmitted through mosquito bites. The parasites lodge in the lymphatic system causing destruction of the healthy vessels and nodes, resulting in lymphedema.

- Obesity

Symptoms of lymphedema

People with lymphedema in their arm or leg may have the following symptoms:

- Swelling that begins in the arm or leg

- A heavy feeling in the arm or leg

- Weakness or less flexibility

- Rings, watches, or clothes that become too tight

- Discomfort or pain

- Tight, shiny, warm, or red skin

- Hardened skin, or skin that does not indent when pressed

- Thicker skin

- Skin that may look like an orange peel (swollen with small indentations)

- Small blisters that leak clear fluid

Symptoms of head and neck lymphedema include:

- Swelling of the eyes, face, lips, neck, or area below the chin

- Discomfort or tightness in any of the affected areas

- Difficulty moving the neck, jaw, or shoulders

- Thickening and scarring of the skin on the neck and face, called fibrosis

- Decreased vision because of swollen eyelids

- Difficulty swallowing, speaking, or breathing

- Drooling or loss of food from the mouth while eating

- Nasal congestion or long-lasting middle ear pain, if swelling is severe

Symptoms of lymphedema may begin slowly and are not always easy to detect. Sometimes the only symptoms may be heaviness or aching in an arm or leg. Other times, lymphedema may begin more suddenly.

If you develop any symptoms of lymphedema, talk with your doctor as soon as possible. You will need to learn how to manage the symptoms so they do not get worse. Because swelling is sometimes a sign of cancer, it is also important to see your doctor to be sure that the cancer has not come back.

How is lymphedema diagnosed?

A doctor is often able to find lymphedema by looking at the affected area. But sometimes he or she will recommend additional tests to confirm a diagnosis, plan treatment, or rule out other causes of the symptoms. These tests may include:

- Measuring the affected part of the body with a tape measure to monitor swelling

- Placing the affected arm or leg into a water tank to calculate the volume of fluid that has built up

- Watching the flow of fluid through the lymph system using an ultrasound. This imaging test uses sound waves to create a picture of the inside of the body. An ultrasound can also be used to rule out blood clots as a cause of the swelling. Venous ultrasonography is the imaging modality of choice in the evaluation of suspected deep vein thrombosis (DVT). Compression ultrasonography with or without Doppler waveform analysis has a high sensitivity (95%) and specificity (96%) for proximal thrombosis; however, the sensitivity is lower for calf veins (73%) 2. Duplex ultrasonography can also be used to confirm the diagnosis of chronic venous insufficiency. Patients with unilateral lower extremity edema who do not demonstrate a proximal thrombosis on duplex ultrasonography may require additional imaging to diagnose the cause of edema if clinical suspicion for DVT remains high.

- Creating a picture of the lymphatic system using an imaging method called lymphoscintigraphy. Indirect radionuclide lymphoscintigraphy, which shows absent or delayed filling of lymphatic channels, is the method of choice for evaluating lymphedema when the diagnosis cannot be made clinically 3. This is a reliable test, but it is not commonly used.

- Having a computed tomography (CT or CAT) scan or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). These tests show the pattern of lymph drainage and whether a tumor or other mass is blocking the flow of the lymphatic system. Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) with venography of the lower extremity and pelvis can be used to evaluate for intrinsic or extrinsic pelvic or thigh DVT 4. Compression of the left iliac vein by the right iliac artery (May-Thurner syndrome) should be suspected in women between 18 and 30 years of age who present with edema of the left lower extremity 5. Magnetic resonance imaging may aid in the diagnosis of musculoskeletal causes, such as a gastrocnemius tear or popliteal cyst. T1-weighted magnetic resonance lymphangiography can be used to directly visualize the lymphatic channels when lymphedema is suspected 6. Doctors do not usually use CT and MRI scans to diagnose lymphedema unless they are concerned about a possible cancer recurrence.

- Using other tools to diagnose lymphedema. These include perometry, which uses infrared light beams, or a bioimpedance spectroscopy, which measures electrical currents flowing through body tissues.

It is also important to make sure another illness is not causing the swelling. Your doctor may perform other tests to rule out heart disease, blood clots, infection, liver or kidney failure, or an allergic reaction. The following laboratory tests are useful for diagnosing systemic causes of edema: brain natriuretic peptide measurement (for congestive heart failure), creatinine measurement and urinalysis (for kidney disease), and hepatic enzyme and albumin measurement (for liver disease). In patients who present with acute onset of unilateral upper or lower extremity swelling, a D-dimer enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay can rule out deep vein thrombosis (DVT) in low-risk patients. However, this test has a low specificity, and D-dimer concentrations may be elevated in the absence of thrombosis 7.

Are there any complications that can arise with lymphedema?

Lymphedema is understood to be a progressive disease and early intervention is recommended to minimize time and age related changes. The swelling may progress without treatment. The skin is prone to thickening and the development of fibrosis and other secondary changes.

When the lymphatic impairment causes the lymph fluid to exceed the lymphatic system’s ability to transport it, an abnormal amount of protein-rich fluid collects in the tissues of the affected area. Left untreated, this stagnant, protein-rich fluid causes tissue channels to increase in size and number, reducing the availability of oxygen. This interferes with wound healing and provides a rich culture medium for bacterial growth that can result in infections: cellulitis, lymphangitis, lymphadenitis, (in severe cases sepsis) and skin ulcers.

It is vital for lymphedema patients to be aware of the symptoms of infection and to seek treatment at the first signs, since recurrent infections, in addition to their inherent danger, further damage the lymphatic system and set up a vicious cycle.

Very rarely, in certain exceptionally severe cases, lymphedema untreated over many years can lead to a form of cancer known as lymphangiosarcoma.

How is lymphedema best treated?

Lymphedema cannot be cured but it can be reduced and managed with appropriate intervention. The stage, location and severity of the lymphedema together with your individual circumstances will influence the most appropriate intervention. Early intervention is recommended.

The purpose lymphedema treatment is to:

- Reduce swelling

- Prevent it from getting worse

- Prevent infection

- Improve how your affected body part looks

- Improve your ability to function

The mainstay of lymphedema treatment involves complex decongestive physiotherapy, which is composed of manual lymphatic drainage massage and multilayer bandages 8. The initial goal is to improve lymphatic fluid resorption until a maximum therapeutic response is reached. The maintenance phase of treatment includes compression stockings at 30 to 40 mm Hg 9. Pneumatic compression devices have been shown to augment standard therapies. One randomized controlled trial of women with breast cancer–related lymphedema showed statistically significant improvement in lymphatic function following one hour of pneumatic compression therapy 10. In a study of 155 patients with cancer- and non–cancer-related lymphedema, 95% of patients noted reduction in limb edema after using pneumatic compression devices at home 11. Surgical debulking or bypass procedures are limited to severe refractory cases 12. Diuretics do not have a role in the treatment of lymphedema 8.

Although treatment can help control lymphedema, it currently does not have a cure. Your doctor may recommend a certified lymphedema therapist (CLT). The certified lymphedema therapist can develop a treatment plan for you, which may include:

- Manual lymphatic drainage (MLD). Manual lymphatic drainage is a gentle but very specific type of skin massage that improves the transport of fluid and waste in your body through the lymphatic system. It helps blocked lymphatic fluid drain properly into the bloodstream and may reduce swelling. For best results, you should begin manual lymphatic drainage treatments as close to the start of lymphedema symptoms as possible. A member of your health care team can refer you to a certified lymphedema therapist (CLT) trained in this technique.

- Exercise. Exercising usually improves the flow of lymph fluid through the lymphatic system and strengthens muscles. A certified lymphedema therapist can show you specific exercises that will improve your range of motion. Ask your doctor or therapist when you can start exercising and which exercises are right for you.

- Compression. Non-elastic bandages and compression garments, such as elastic sleeves, place gentle pressure on the affected area. This helps prevent fluid from refilling and swelling after decongestive therapy (see below). There are several options, depending on the location of the lymphedema. All compression devices apply the most pressure farthest from the center of the body and less pressure closer to the center of the body. Compression garments must fit properly and should be replaced every 3 to 6 months.

- Complete decongestive therapy. This is also known as complex decongestive therapy. It combines skin care, manual lymphatic drainage, exercise, and compression. A doctor who specializes in lymphedema or a certified lymphedema therapist should do this therapy. The therapist will also tell you how to do the necessary techniques by yourself at home and how often to do them. Ask your doctor for a referral.

- Skin care. Lymphedema can increase the risk of infection. So it is important to keep the affected area clean, moisturized, and healthy. Apply moisturizer each day to prevent chapped skin. Avoid cuts, burns, needle sticks, or other injury to the affected area. If you shave, use an electric razor to reduce the chance of cutting the skin. When you are outside, wear a broad-spectrum sunscreen that protects against both UVA and UVB radiation and has a sun protection factor (SPF) of at least 30. If you do cut or burn yourself, wash the injured area with soap and water and use an antibiotic cream as directed by your health care team.

- Elevation. Keeping your affected limb raised helps to reduce swelling and encourage fluid drainage through the lymphatic system. But it is often difficult to keep a limb raised for a long time.

- Low-level laser treatments. A small number of clinical trials have found that low-level laser treatment could provide some relief from lymphedema after removal of the breast, particularly in the arms.

- Medications. Your doctor may prescribe antibiotics to treat infections or drugs to relieve pain when necessary.

- Physical therapy. If you have trouble swallowing or other issues from lymphedema of the head and neck, you may need physical therapy.

Relieving side effects is an important part of cancer care and treatment. This is called palliative care or supportive care. Talk with your health care team about any lymphedema symptoms you have.

Table 1. Diagnosis and management of common causes of localized edema

| Cause | Onset and location | Examination findings | Evaluation methods | Treatment |

| Unilateral predominance | ||||

| Chronic venous insufficiency | Onset: chronic; begins in middle to older age Location: lower extremities; bilateral distribution in later stages | Soft, pitting edema with reddish-hued skin; predilection for medial ankle/calf Associated findings: venous ulcerations over medial malleolus; weeping erosions | Duplex ultrasonography Ankle-brachial index to evaluate for arterial insufficiency | Compression stockings Pneumatic compression device if stockings are contraindicated Horse chestnut seed extract Skin care (e.g., emollients, topical steroids) |

| Complex regional pain syndrome type 1 (reflex sympathetic dystrophy) | Onset: chronic; following trauma or other inciting event Location: upper or lower extremities; contralateral limb at risk regardless of trauma | Soft tissue edema distal to affected limb Associated findings: (early) warm, tender skin with diaphoresis; (late) thin, shiny skin with atrophic changes | History and examination Radiography Three-phase bone scintigraphy Magnetic resonance imaging | Systemic steroids Topical dimethyl sulfoxide solution Physical therapy Tricyclic antidepressants Calcium channel blockers |

| deep venous thrombosis (DVT) | Onset: acute Location: upper or lower extremities | Pitting edema with tenderness, with or without erythema; positive Homans sign | D-dimer assay Duplex ultrasonography Magnetic resonance venography to rule out pelvic or thigh deep venous thrombosis (DVT) (if clinical suspicion is high), or extrinsic venous compression (May-Thurner syndrome in patients with unexplained left-sided deep venous thrombosis (DVT)) Consider hypercoagulability workup | Anticoagulation therapy Compression stockings to prevent postthrombotic syndrome Thrombolysis in select patients |

| Lymphedema | Onset: chronic; insidious; often following lymphatic obstruction from trauma or surgery Location: upper or lower extremities; bilateral in 30% of patients | Early: dough-like skin; pitting Late: thickened, verrucous, fibrotic, hyperkeratotic skin Associated findings: inability to tent skin over second digit, swelling of dorsum of foot with squared off digits, painless heaviness in extremity | Clinical diagnosis Lymphoscintigraphy T1-weighted magnetic resonance lymphangiography | Complex decongestive physiotherapy Compression stockings with adjuvant pneumatic compression devices Skin care Surgery in limited cases |

| Bilateral predominance | ||||

| Lipedema (lipoedema) | Onset: chronic; begins around or after puberty Location: predominantly lower extremities; involves thighs, legs, buttocks; spares feet, ankles, and upper torso | Nonpitting edema; increased distribution of soft, adipose tissue Associated findings: medial thigh and tibial tenderness; fat pad anterior to lateral malleoli | Clinical diagnosis | No effective treatment Weight loss does not improve edema |

| Medication-induced edema | Onset: weeks after initiation of medication; resolves within days of stopping offending medication Location: lower extremities | Soft, pitting edema | Clinical history suggesting recent initiation of offending medication | Cessation of medication |

| Obstructive sleep apnea | Onset: chronic Location: lower extremities | Mild, pitting edema Associated findings: daytime fatigue, snoring, obesity | Suggestive clinical history Polysomnography Echocardiography | Positive pressure ventilation Treatment of pulmonary hypertension if suggested on echocardiography |

How often might I need to have manual lymphatic drainage?

This will depend on your individual situation. Having a regular course of manual lymphatic drainage may be more effective than a one-off treatment. Sometimes manual lymphatic drainage is used several times a week, alongside treatments such as compression garments or bandages, for example to reduce swelling in people with lymphedema. The way duration of treatments varies depending on the stage of lymphodema you have, for example, intensive treatment may be for 2-4 weeks and less intensive treatments could last for months or for years 13.

Lipedema also called lipoedema, is a chronic condition whereby fat cells abnormally build up in the hips, buttocks, legs and occasionally arms of women (and, far more rarely, men), resulting in often painful pockets of fat that do not go away with exercise or dietary changes. Lipoedema is more common in women. It usually affects both sides of the body equally. You may also have pain, tenderness or heaviness in the affected limbs, and you may bruise easily. Lipoedema can also cause knock knees, flat feet and joint problems, which can make walking difficult. In lipoedema, manual lymphatic drainage may be effective as a weekly treatment, and some people find that a monthly treatment or less is enough to get their lymphatic system ‘back on track’.

Do I need a compression garment?

Compression garments are used to maintain reduction achieved in an intensive treatment, prevent progression of the lymphedema or may be prescribed to reduce the risk of the onset of lymphedema during air travel or other activities which may exacerbate existing lymphedema. Your certified lymphedema therapist will be able to advise whether you need a garment and how to use it. Some certified lymphedema therapists may supply garments whilst others will refer you to an appropriate fitter.

Should I protect my lymphedema limb?

It is preferable to use the unaffected limb for blood pressure recording, venepuncture, injections and IV drips if possible. However the recommendations to protect the lymphedema and lymphedema-vulnerable arm from all these procedures are based on experience or anecdote in the absence of research.

Limited research has been undertaken following patients with arm lymphedema who had venepunctures or injections performed in the affected limb. This research was performed by experienced nurses using correct infection control techniques. This research showed no worsening of the lymphedema. There is currently no robust research evidence that blood pressure monitoring worsens or triggers lymphedema.

Recent research has shown that the normal use and the exercise of the limb vulnerable to or with lymphedema has a positive effect and is important to good lymphedema management.

It is important to prevent skin infection and cellulitis by careful skin care and cleanliness.

Can my lymphedema get worse?

If lymphedema remains untreated it may progress, however with treatment by a certified lymphedema therapist, careful monitoring and good self management this usually doesn’t occur.

Manual lymphatic drainage benefits

5 key benefits of manual lymphatic drainage:

- Deeply relaxing

- Decongestive (removes lymphedema)

- Pain relieving

- Improves wound healing and scarring

- Detoxifying

Does manual lymphatic drainage work?

Research studies haven’t clearly proven the effectiveness of manual lymphatic drainage, but they have shown that complete decongestive therapy (CDT) is effective — and complete decongestive therapy (CDT) usually includes manual lymphatic drainage 13. Manual lymphatic drainage is effective both as a preventative treatment and as a postoperative rehabilitation treatment, and has optimal results when it is combined with the other elements of Complete Decongestive Therapy (CDT) 13. Manual lymphatic drainage also increases blood flow in deep and superficial veins 14.

Manual lymphatic drainage may be useful for treating many conditions such as:

- Lymphedema – primary or secondary lymphedema

- Lipodema

- Post surgery swelling

- Post-traumatic edema

- Chronic venous insufficiency 14

- Lyme disease

- Chronic sinusitis

- Stroke

- Head injuries or concussions

- Parkinson’s disease

- Amputation or phantom limb pains

- Burns

- Fractures

- Constipation

- Swelling during pregnancy

- Whiplash syndrome

- Dupuytren’s contracture

- Bursitis

- Tendinitis, tendinous, Periarthritic syndrome, tendosynovitis, epicondylitis

- Scleroderma

- Lupus erythematosis

- Gout in subacute or chronic phase

- Spondylosis

- Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

- Cystic fibrosis

- Diverticulosis

- Acne and rosacea

- Alzheimer’s disease

- Palliative care – provision of comfort and pain relief when other physical therapies are no longer appropriate 15

- Manual lymphatic drainage may be used as a complement in therapies for patients with psychological stress 16

- Manual lymphatic drainage may be effective for reducing intracranial pressure in severe cerebral diseases 17

Manual lymphatic drainage techniques

Manual lymphatic drainage is intended to stimulate lymph nodes and increase rhythmic contractions of the lymphatics to enhance their activity so that stagnant lymphatic fluid can be rerouted.

Manual lymphatic drainage is composed of four main strokes:

- Stationary circles,

- Scoop technique,

- Pump technique, and

- Rotary technique.

The videos below give a very brief explanation of Manual Lymphatic Drainage.

Different approaches:

- Vodder – Different kinds of hand motions are used on the body depending on the part being treated. It also includes treatment of fibrosis

- Foldi – Based on the Vodder technique, this method lays emphasis on thrust and releaxation. It helps in management of edema through ‘encircling strokes’.

- Casley-Smith – This method involves use of small and gentle effleurage movements with the side of the hand.

- Leduc – It involves use of special ‘call up’ (or enticing) and ‘reabsorption’ movements which reflet how lymph is absorbed first in the initial lymphatics and then into larger lymphatics 18.

The most appropriate techniques, optimal frequency and indications for manual lymphatic drainage, as well as the benefits of treatment, all remain to be clarified, but the different methods have several aspects in common 15:

- Usually performed with the patient in the lying position

- Starts and ends with deep diaphragmatic breathing

- The unaffected lymph nodes and region of the body are treated first

- Moves proximal to distal to drain the affected areas

- Slow and rhythmical movements

- Uses gentle pressure

Self manual lymphatic drainage

Self-manual lymphatic drainage is a large part of maintaining your reduced limb size. It is important to continue manual lymphatic drainage on your own to help keep your lymph vessels working as best as they can. Your certified lymphedema therapist will teach you how to perform Self-manual lymphatic drainage and how often.

Manual lymphatic drainage side effects

Possible side effects of manual lymphatic drainage:

- Increased relaxation

- Increase in urination

- Possible diarrhea

- Fatigue

- Possible nausea

- Dizziness when first sitting up

- Decreased edema

- Increase in energy

Manual lymphatic drainage contraindications

Contraindications for manual lymphatic drainage include:

- Major organ failure

- Acute renal failure

- Cardiac decompensation or untreated congestive heart failure

- Hypotension

- Fever

- Acute inflammation caused by pathogenic germs (bacteria, fungi, viruses). The germs could be spread by the manual lymph drainage, with resulting blood poisoning (sepsis).

- Infection must be on antibiotics for at least 48 hours.

- Influenza

- Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) within two years

- Blood thinners (depends on integrity of the skin)

- Conditions of chronic inflammation need to be approached cautiously.

- Recent asthma attack

- First trimester of pregnancy

- Any trimester of pregnancy when still experiencing morning sickness

- Dental infection

- Those undergoing active oncology treatments would need permission from their treatment team.

- Manual Lymph Drainage History (MLD). https://vodderschool.com/manual_lymph_drainage_history[↩]

- Kearon C, Julian JA, Newman TE, Ginsberg JS. Noninvasive diagnosis of deep venous thrombosis. McMaster Diagnostic Imaging Practice Guidelines Initiative [published correction appears in Ann Intern Med. 1998;129(5):425]. Ann Intern Med. 1998;128(8):663–677.[↩]

- Rockson SG. Current concepts and future directions in the diagnosis and management of lymphatic vascular disease. Vasc Med. 2010;15(3):223–231.[↩]

- Wolpert LM, Rahmani O, Stein B, Gallagher JJ, Drezner AD. Magnetic resonance venography in the diagnosis and management of May-Thurner syndrome. Vasc Endovascular Surg. 2002;36(1):51–57.[↩]

- Naik A, Mian T, Abraham A, Rajput V. Iliac vein compression syndrome: an underdiagnosed cause of lower extremity deep venous thrombosis. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(7):E12–E13.[↩]

- Lawenda BD, Mondry TE, Johnstone PA. Lymphedema: a primer on the identification and management of a chronic condition in oncologic treatment. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59(1):8–24.[↩]

- Kesieme E, Kesieme C, Jebbin N, Irekpita E, Dongo A. Deep vein thrombosis: a clinical review. J Blood Med. 2011;2:59–69.[↩]

- Edema: Diagnosis and Management. Am Fam Physician. 2013 Jul 15;88(2):102-110. https://www.aafp.org/afp/2013/0715/p102.html[↩][↩][↩]

- Stanisic MG, Gabriel M, Pawlaczyk K. Intensive decongestive treatment restores ability to work in patients with advanced forms of primary and secondary lower extremity lymphoedema. Phlebology. 2012;27(7):347–351.[↩]

- Adams KE, Rasmussen JC, Darne C, et al. Direct evidence of lymphatic function improvement after advanced pneumatic compression device treatment of lymphedema. Biomed Opt Express. 2010;1(1):114–125.[↩]

- Ridner SH, McMahon E, Dietrich MS, Hoy S. Home-based lymphedema treatment in patients with cancer-related lymphedema or noncancer-related lymphedema. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2008;35(4):671–680.[↩]

- Tiwari A, Cheng KS, Button M, Myint F, Hamilton G. Differential diagnosis, investigation, and current treatment of lower limb lymphedema. Arch Surg. 2003;138(2):152–161.[↩]

- I., Tzani & M., Tsichlaki & Papathanasiou, George & Zerva, E. & Dimakakos, Evangelos. (2018). Physiotherapeutic rehabilitation of lymphedema: State-of-the-art. Lymphology. 51. 1-12.[↩][↩][↩]

- Crisóstomo RS, Candeias MS, Armada-da-Silva PA. Venous flow during manual lymphatic drainage applied to different regions of the lower extremity in people with and without chronic venous insufficiency: a cross-sectional study.Physiotherapy. 2016 Feb 1. pii: S0031-9406(16)00023-7.[↩][↩]

- Lymphoedema Framework. Best Practice for the Management of Lymphoedema. International consensus. London: MEP Ltd, 2006.[↩][↩]

- Jung-Myo S, Sung-Joong K. Manual Lymph Drainage Attenuates Frontal EEG Asymmetry in Subjects with Psychological Stress: A Preliminary Study. J Phys Ther Sci. 2014 Apr; 26(4): 529–531.[↩]

- Roth C, Stitz H, Roth C, Ferbert A, Deinsberger W, Pahl R et. al. Craniocervical manual lymphatic drainage and its impact on intracranial pressure – a pilot study. Eur J Neurol. 2016 Sep;23(9):1441-6.[↩]

- Williams AF. Manual lymphatic drainage: Exploring the history and evidence base. British Journal of Community Nursing. 2010;15(4):S18-24. DOI: 10.12968/bjcn.2010.15.Sup3.47365[↩]