Melanoma skin cancer

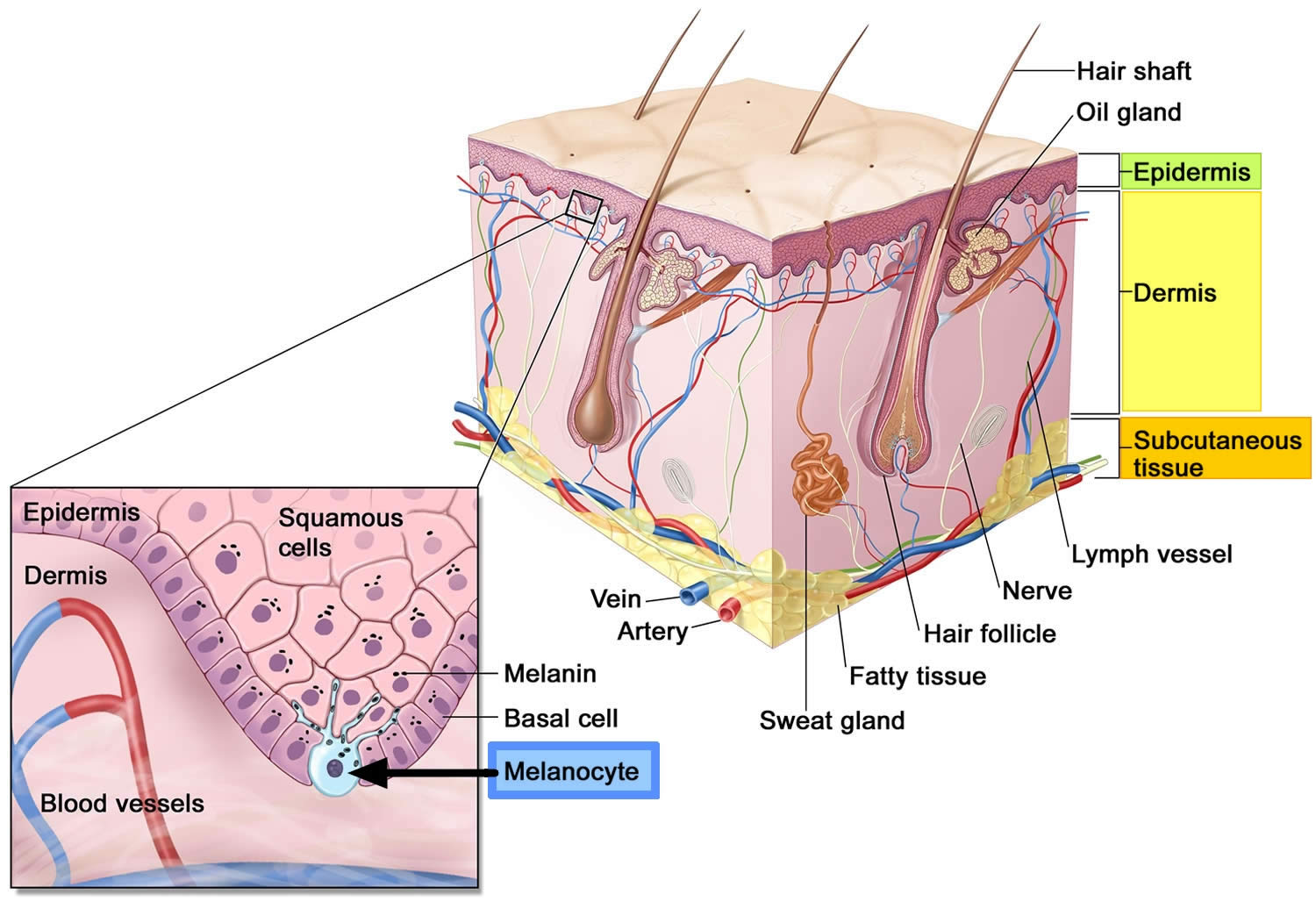

Melanoma also called malignant melanoma or cutaneous melanoma, is the most serious type of skin cancer that begins in the melanocytes of the skin (a type of skin cells that produce melanin and melanin gives your skin its color) (see Figure 1 below). Melanomas can develop anywhere on the skin, but they are more likely to start on the trunk (chest and back) in men and on the legs in women. The neck and face are other common sites. Having darkly pigmented skin lowers your risk of melanoma at these more common sites, but anyone can get melanoma on the palms of the hands, soles of the feet, or under the nails. Melanomas in these areas make up a much larger portion of melanomas in African Americans than in whites. Melanoma can also form in your eyes and, rarely, inside your body, such as in your nose, mouth, throat, genitals and anal area, but these are much less common than melanoma of the skin. While melanoma is much less common than some other types of skin cancer, it’s more dangerous because it’s much more likely to spread to other parts of the body than the other two skin cancer types (basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma) if not caught and treated early.

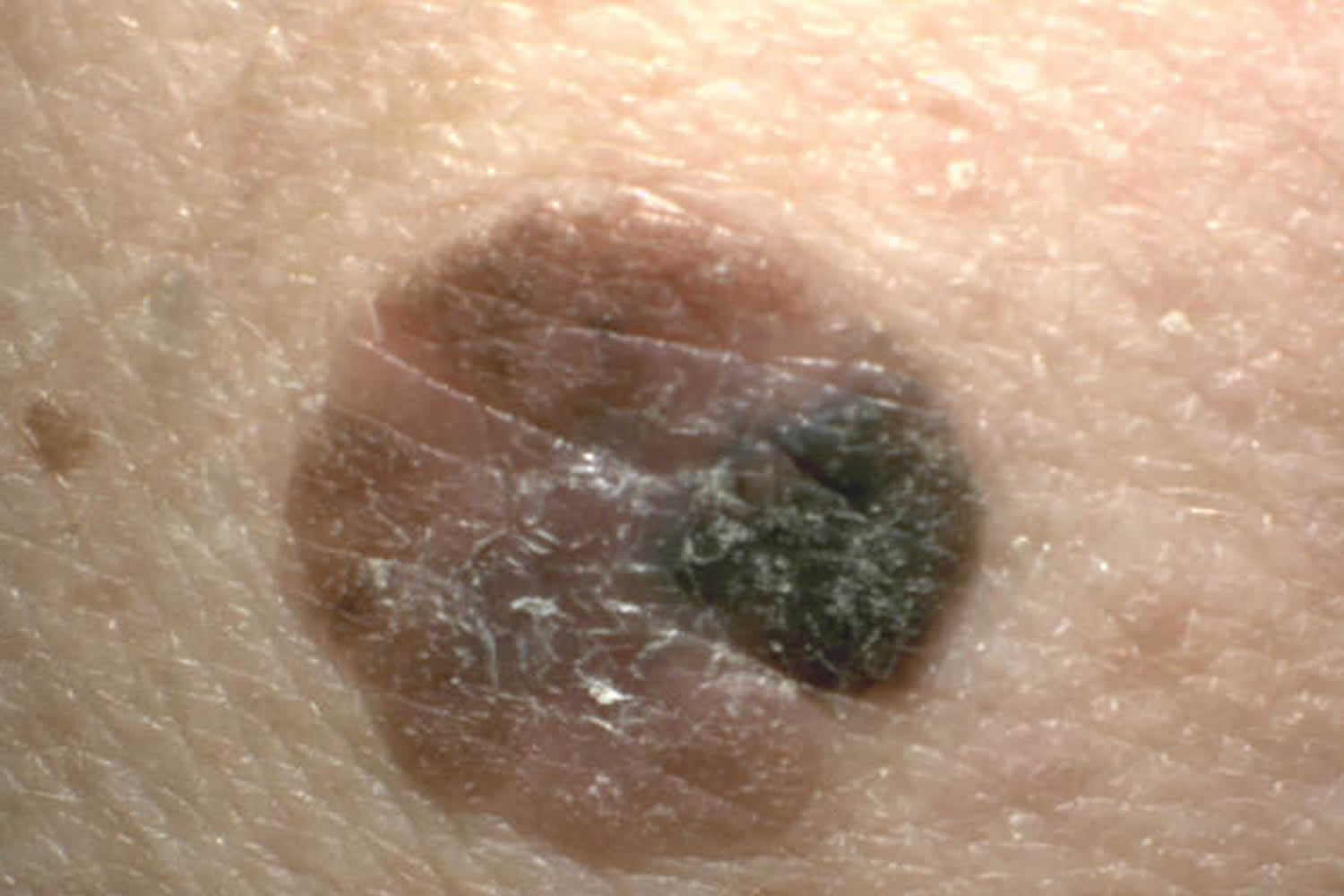

Melanoma may appear on the skin suddenly without warning but also can develop within an existing mole. The first sign of melanoma is often a mole that changes size, shape or color. Most melanoma cells still make melanin, so melanoma tumors are usually brown or black. But some melanomas do not make melanin and can appear pink, tan, or even white.

The ABCDE checklist can be used to check for the main warning signs of melanoma:

- A is for asymmetrical shape. Look for moles with irregular shapes, such as two very different-looking halves. Melanomas usually have 2 very different halves and are an irregular shape

- B is for irregular border. Look for moles with irregular, notched or scalloped borders — characteristics of melanomas. Melanoma often has an irregular appearance, however, if a symmetrical lesion continues to grow out of proportion to the patient’s other moles, especially if aged > 45, then melanoma must be considered

- C is for changes in color. Look for growths that have many colors (a mix of 2 or more colors) or an uneven distribution of color.

- D is for diameter. Look for new growth in a mole larger than 1/4 inch (about 6 millimeters).

- Melanoma grow at different rates – even if the lesion is not changing, if it looks suspicious or if you notice any skin changes that seem unusual make an appointment with your doctor.

- E is for evolving. Look for changes over time, such as a mole that grows in size or that changes color or shape. Moles may also evolve to develop new signs and symptoms, such as new itchiness or bleeding.

It is also important to note that cancerous (malignant) moles vary greatly in appearance. Some may show all of the changes listed above, while others may have only one or two unusual characteristics.

Melanoma accounts for only about 1% of skin cancers but causes a large majority of skin cancer deaths 1. The overall incidence of melanoma have been rising rapidly over the past few decades, but this has varied by age. The risk of melanoma increases as people age. The average age of people when melanoma skin cancer is diagnosed is 65. But melanoma is not uncommon even among those younger than 30 (especially young women). Melanoma is more common in men overall, but before age 50 the rates are higher in women than in men. Melanoma rates in the United States doubled from 1988 to 2019, and worldwide, the number of melanoma diagnoses are expected to increase by more than 50% by 2040 2.

The American Cancer Society’s estimates for melanoma in the United States for 2022 are 2:

- New cases: About 99,780 new melanomas will be diagnosed (about 57,180 in men and 42,600 in women).

- Deaths: About 7,650 people are expected to die of melanoma (about 5,080 men and 2,570 women).

- 5-Year Relative Survival: 93.7%. Relative survival is an estimate of the percentage of patients who would be expected to survive the effects of their cancer. It excludes the risk of dying from other causes. Because survival statistics are based on large groups of people, they cannot be used to predict exactly what will happen to an individual patient. No two patients are entirely alike, and treatment and responses to treatment can vary greatly.

- Percentage of All Cancer Deaths: 1.3%.

- Melanoma is more common in men than women and among individuals of fair complexion and those who have been exposed to natural or artificial sunlight (such as tanning beds) over long periods of time. There are more new cases among whites than any other racial/ethnic group.

- Rate of New Cases and Deaths per 100,000: The rate of new cases of melanoma of the skin was 21.5 per 100,000 men and women per year. For melanoma of the skin, death rates are higher among the middle-aged and elderly. The death rate was 2.2 per 100,000 men and women per year. These rates are age-adjusted and based on 2015–2019 cases and deaths.

- Lifetime Risk of Developing Cancer: Approximately 2.1 percent of men and women will be diagnosed with melanoma of the skin at some point during their lifetime, based on 2017–2019 data.

- In 2019, there were an estimated 1,361,282 people living with melanoma of the skin in the United States.

Melanoma of the skin represents 5.2% of all new cancer cases in the U.S. Melanoma is more than 20 times more common in whites than in African Americans. Overall, the lifetime risk of getting melanoma is about 2.6% (1 in 38) for whites, 0.1% (1 in 1,000) for Blacks, and 0.6% (1 in 167) for Hispanics 1. The risk for each person can be affected by a number of different factors.

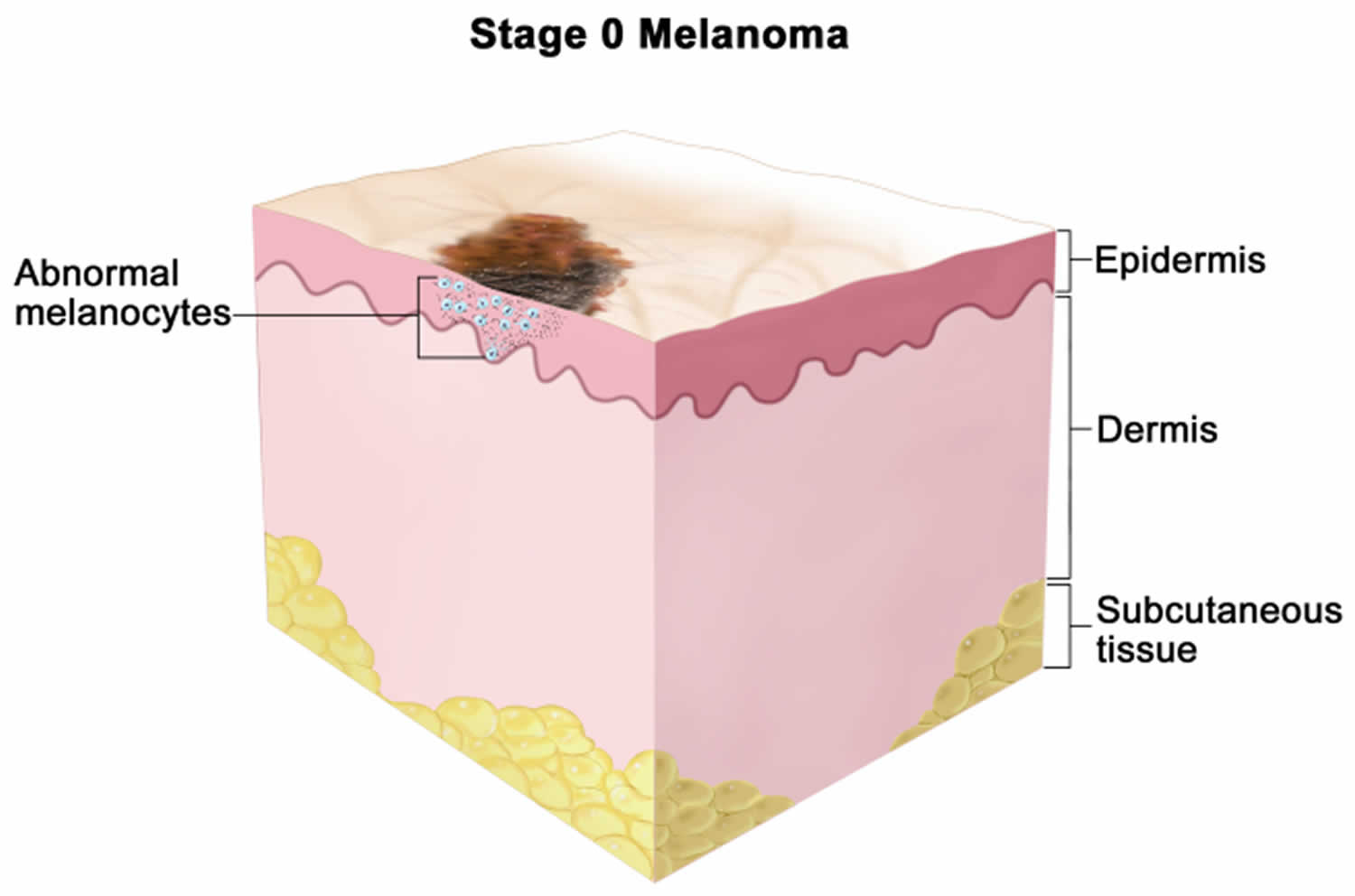

Normal melanocytes are found in the basal layer of the epidermis (the outer layer of skin) (see Figure 1). Melanocytes produce a protein called melanin, which protects skin cells by absorbing ultraviolet (UV) radiation. Melanocytes are found in equal numbers in black and white skin, but melanocytes in black skin produce much more melanin. People with dark brown or black skin are very much less likely to be damaged by UV radiation than those with white skin.

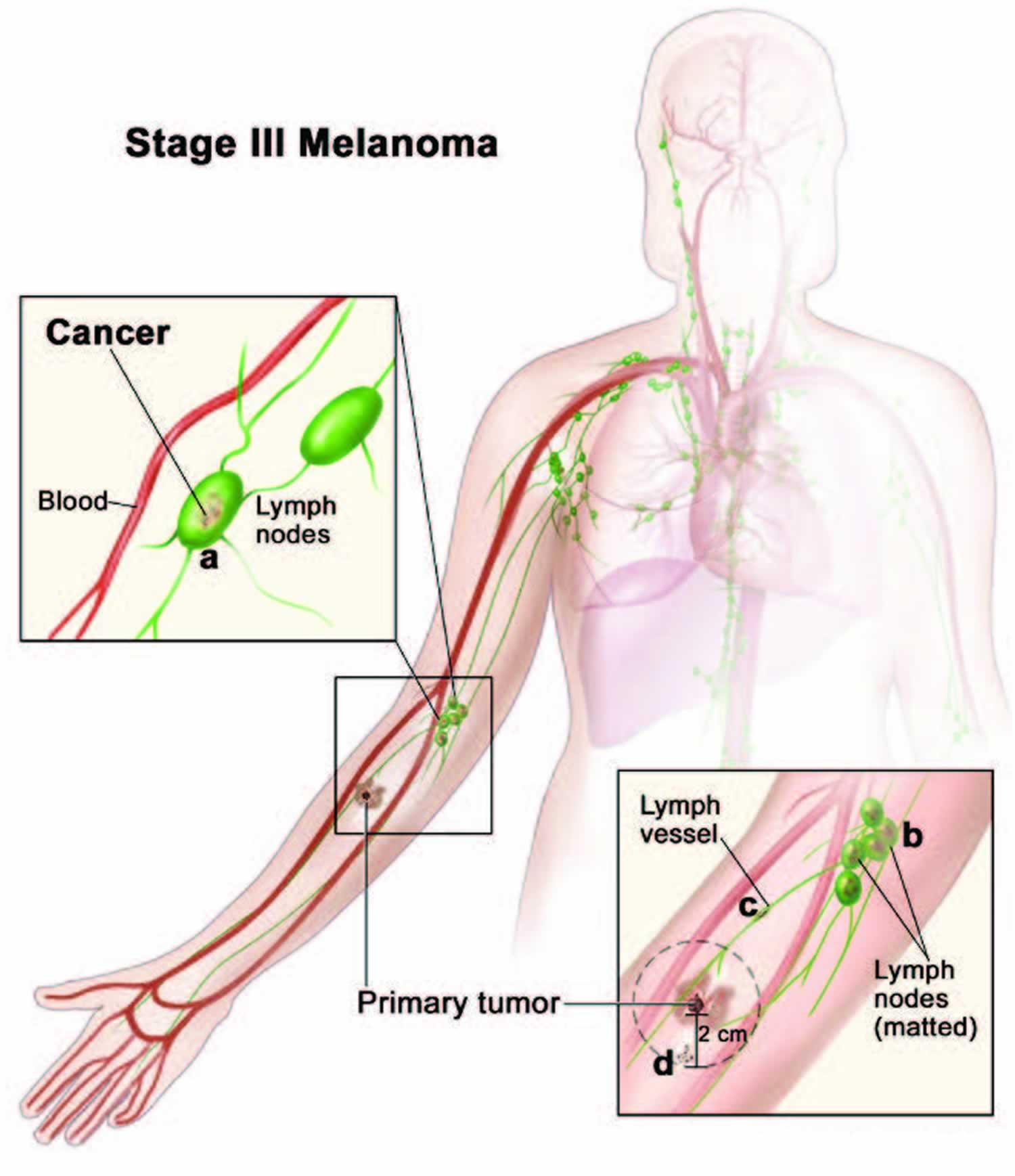

Non-cancerous growth of melanocytes results in moles (benign melanocytic nevi) and freckles (ephelides and lentigines). The cancerous growth of melanocytes results in melanoma. Melanoma is described as:

- In situ melanoma, if the skin cancer is confined to the epidermis

- Invasive melanoma, if the skin cancer has spread into the dermis

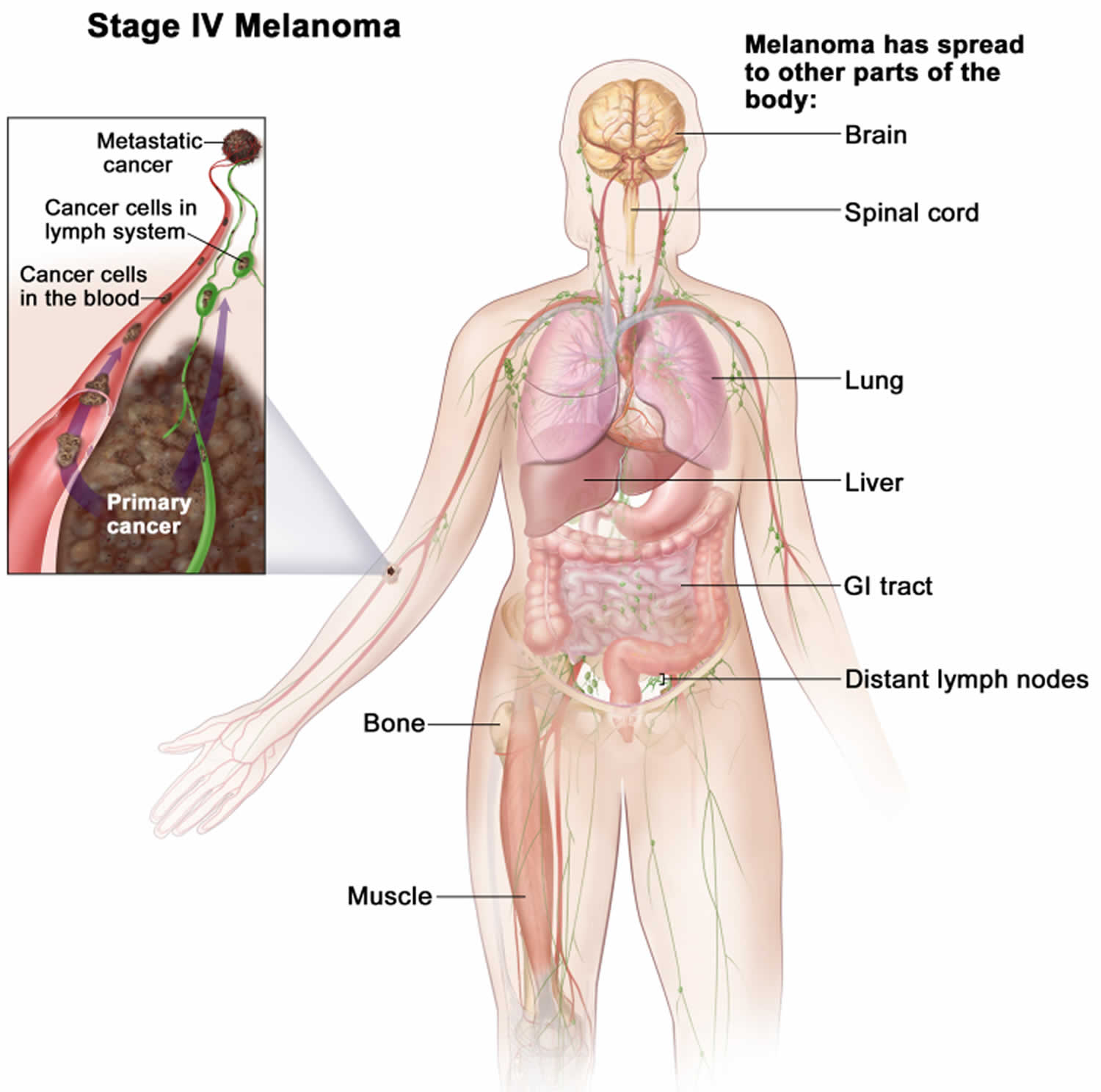

- Metastatic melanoma, if the skin cancer has spread to other tissues.

Most melanomas are brought to a doctor’s attention because of signs or symptoms a person is having. If you have an abnormal area on your skin that might be cancer, your doctor will examine it and might do tests to find out if it is melanoma, another type of skin cancer, or some other skin condition. If melanoma is found, other tests may be done to find out if it has spread to other areas of the body.

The best treatment for your melanoma depends on the size and stage of cancer, your overall health, and your personal preferences. Treatment for early-stage melanomas usually includes surgery to remove the melanoma. A very thin melanoma may be removed entirely during the biopsy and require no further treatment. Otherwise, your surgeon will remove the cancer as well as a border of normal skin and a layer of tissue beneath the skin. For people with early-stage melanomas, this may be the only treatment needed.

If melanoma has spread beyond the skin, treatment options may include:

- Surgery to remove affected lymph nodes. If melanoma has spread to nearby lymph nodes, your surgeon may remove the affected nodes. Additional treatments before or after surgery also may be recommended.

- Immunotherapy. Immunotherapy is a drug treatment that helps your immune system to fight cancer. Your body’s disease-fighting immune system might not attack cancer because the cancer cells produce proteins that help them hide from the immune system cells. Immunotherapy works by interfering with that process. Immunotherapy is often recommended after surgery for melanoma that has spread to the lymph nodes or to other areas of the body. When melanoma can’t be removed completely with surgery, immunotherapy treatments might be injected directly into the melanoma.

- Targeted therapy. Targeted drug treatments focus on specific weaknesses present within cancer cells. By targeting these weaknesses, targeted drug treatments can cause cancer cells to die. Cells from your melanoma may be tested to see if targeted therapy is likely to be effective against your cancer. For melanoma, targeted therapy might be recommended if the cancer has spread to your lymph nodes or to other areas of your body.

- Radiation therapy. This treatment uses high-powered energy beams, such as X-rays and protons, to kill cancer cells. Radiation therapy may be directed to the lymph nodes if the melanoma has spread there. Radiation therapy can also be used to treat melanomas that can’t be removed completely with surgery. For melanoma that spreads to other areas of the body, radiation therapy can help relieve symptoms.

- Chemotherapy. Chemotherapy uses drugs to kill cancer cells. Chemotherapy can be given intravenously, in pill form or both so that it travels throughout your body. Chemotherapy can also be given in a vein in your arm or leg in a procedure called isolated limb perfusion. During this procedure, blood in your arm or leg isn’t allowed to travel to other areas of your body for a short time so that the chemotherapy drugs travel directly to the area around the melanoma and don’t affect other parts of your body.

Figure 1. Anatomy of the skin

Footnote: Anatomy of the skin, showing the epidermis, dermis, and subcutaneous tissue. Melanocytes are in the layer of basal cells at the deepest part of the epidermis.

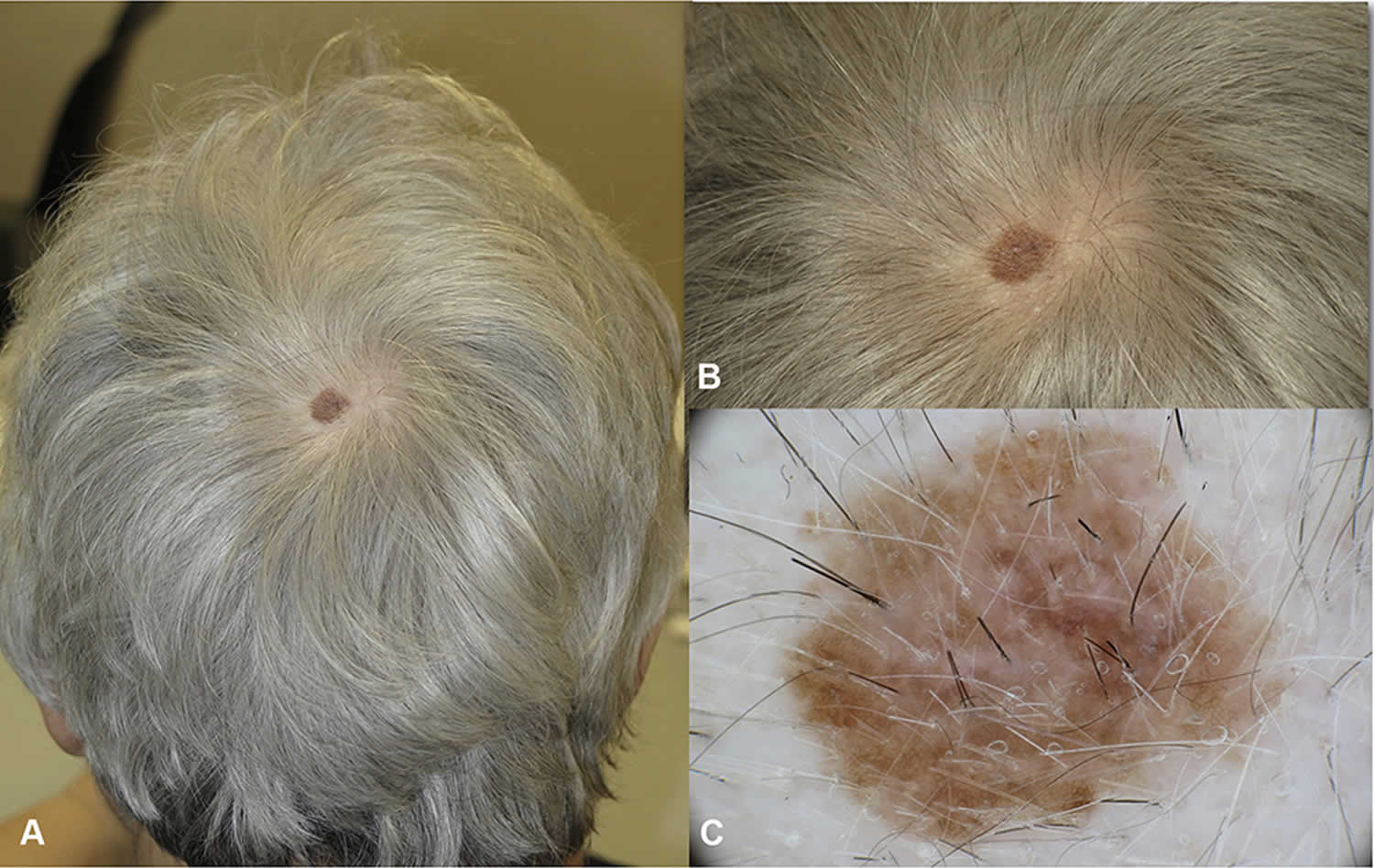

Figure 2. Melanoma on scalp

Footnote: In situ melanoma (or Stage 0 melanoma) of the vertex in a 68 year-old woman. (A) The lesion was arising in hair bearing scalp, the patient was not aware of the macule which was noticed by the hair dresser. (B) Close up clinical image, a flat brown macule 1 cm in diameter. (C and D) In dermoscopy atypical network and regression are detected. No non-prevalent benign pattern.

[Source 3 ]Figure 3. Melanoma on face

[Source 4 ]Skin cancer types

Skin cancer is a cancer that occurs when your skin cells grow abnormally and out of control, usually from too much exposure to ultraviolet (UV) radiation from the sun. This uncontrolled growth of abnormal cells forms a tumor in the skin. Tumors are either benign (non-cancerous), or malignant (cancerous tumors that spread through the body, causing damage).

Skin cancers are named according to the cells in which they form. There are 3 main types:

- Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) begins in the lower segment of cells of the epidermis (your outer layer of skin) called the basal cell layer. Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) tend to grow slowly, and rarely spread to other parts of the body.

- Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) grows from the flat cells found in the top layer of your epidermis. Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) can grow quickly on the skin over several weeks or months. Bowen’s disease is an early form of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) that hasn’t grown beyond the top layer of skin.

- Melanoma grows from cells called melanocytes — cells that give your skin its color. Melanoma is the rarest type of skin cancer (accounting for 1 to 2% of cases) but is considered the most serious because it can spread quickly (metastasize) throughout the body.

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) are also called non-melanoma skin cancers. Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) represents more than 2 in 3 non-melanoma skin cancers, and around 1 in 3 are squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). There are other types of non-melanoma skin cancers, but they are rare.

Other types of non-melanoma skin cancers include:

- Merkel cell carcinoma

- Kaposi sarcoma

- Cutaneous (skin) lymphoma

- Skin adnexal tumors (tumors that start in hair follicles or skin glands)

- Various types of sarcomas

Together, these types account for less than 1% of all skin cancers.

Melanoma types

The American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) identifies five different forms of extraocular melanoma 5:

- Lentigo maligna melanoma,

- Superficial spreading melanoma,

- Nodular melanoma,

- Acral-lentiginous melanoma,

- Mucosal lentiginous melanoma.

Eighty to 85% of melanomas are lentigo maligna melanoma, superficial spreading melanoma, or nodular melanoma. These different forms of melanoma represent distinct pathologic entities that have different clinical and biologic characteristics. The differential clinical features of these common types of melanoma are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Common types of melanoma

| Type of Melanoma | Common Locations | Median Age (years) | Sex Predilection | Duration | Identifying Features of Radial Growth Phase* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lentigo maligna melanoma | Sun-exposed surfaces (head and neck most common) | 70 | None | 5 – 15 years | Flat. Shades of tan to black Frequent areas of hypopigmentation |

| Superficial spreading melanoma | All body surfaces | 56 | Males: head, neck, trunk Females: lower legs | 1 – 5 years | Flat to slightly raised Irregular margins. Shades of brown, black, pink. Areas of hypopigmentation |

| Nodular melanoma | All body surfaces | 49 | None overall Males: head, neck, trunk | 1 month – 2 years | None |

| Acral-lentiginous melanoma | Volar and subungual areas | 59 | Slight female predominance | 2 months – 10 years | Tan to dark-brown macule |

| Mucosal lentiginous melanoma | Oral, ocular, and genital mucosa | 56 | Slight male preponderance but varies from area to area | 4 – 20 years | Tan to dark-brown macular area |

Footnote: * The invasive tumors in each melanoma subtype are basically similar, varying from low convex to polypoid in shape and from dark blue-black to light tan or even (amelanotic) reddish pink in color. They are usually hairless and may be ulcerated.

[Source 5 ]Superficial spreading melanoma

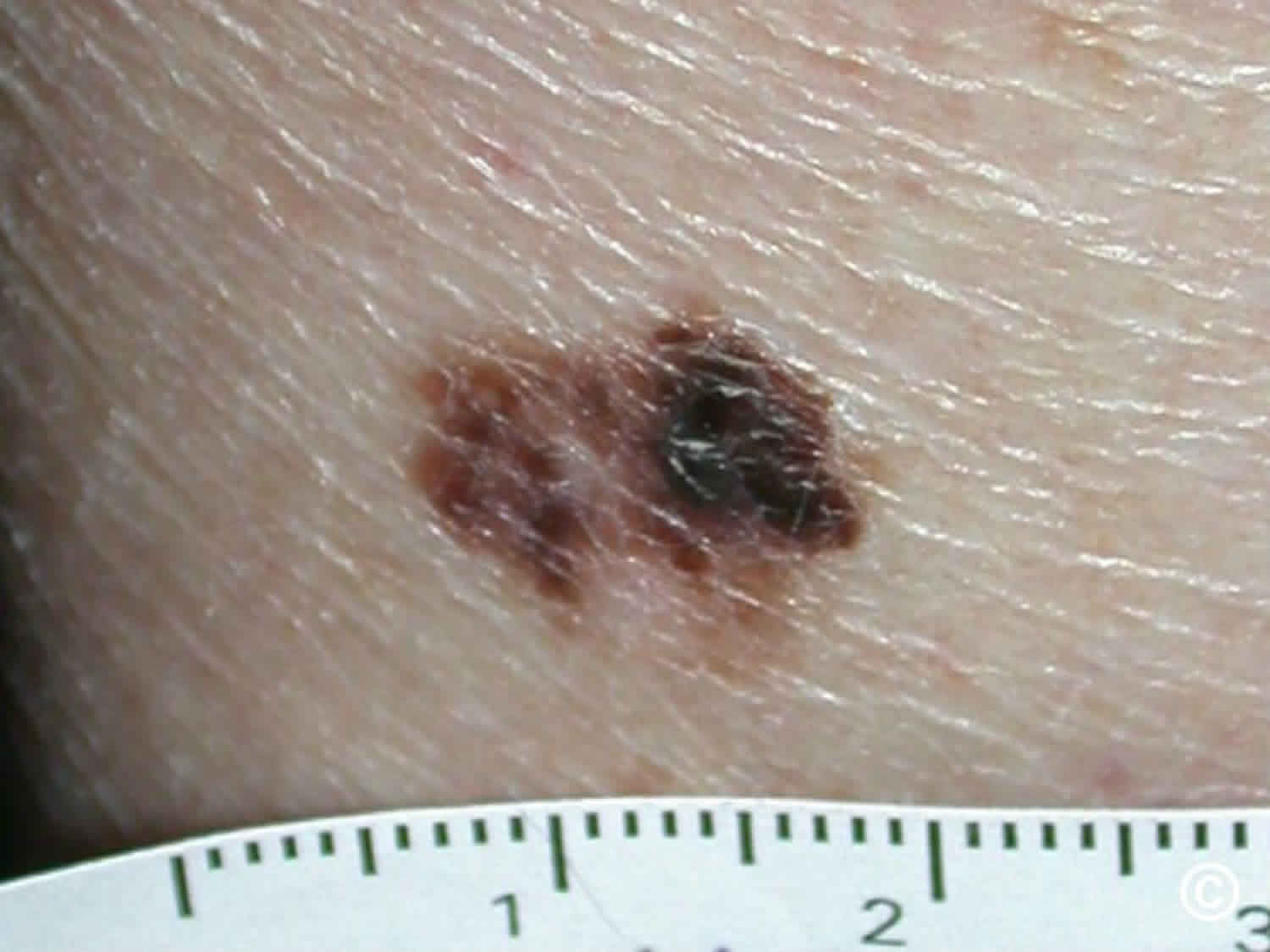

Superficial spreading melanoma is the most common type of melanoma, accounting for approximately 70% of all melanomas 5. Superficial spreading melanoma is a form of melanoma in which the malignant cells tend to stay within the epidermis (‘in situ’ phase) for a prolonged period (months to decades) 6. At first, superficial spreading melanoma grows horizontally in the skin – this is known as the radial growth phase, presenting as a slowly-enlarging flat area of discolored skin.

Superficial spreading melanoma generally arises in a preexisting lesion and is the lesion most commonly associated with pigmented dysplastic nevus syndrome. Superficial spreading melanoma may have a relatively long natural history. Typically, diagnosis follows an increased rate of change in a precursor lesion that had exhibited minor change over several years. Early in their evolution, superficial spreading melanomas usually appear flat, with irregular borders. Notching of the border is particularly characteristic. The lesions are usually multicolored with shades of tan, brown, black, red, and white. Amelanotic areas often represent areas of regression. As the lesion grows, it may develop an irregular surface. superficial spreading melanomas tend to occur throughout adulthood, with a peak incidence in the fifth decade of life. Most commonly, they occur on the head, neck, and trunk in males and on the extremities in females.

An unknown proportion of superficial spreading melanoma become invasive, that is, the melanoma cells cross the basement membrane between the epidermis and dermis and malignant melanocytes enter the dermis 6. A rapidly-growing nodular melanoma can arise within superficial spreading melanoma and proliferate deeply within the skin.

The initial treatment of a superficial spreading melanoma is excision; the lesion should be completely excised with a 2 mm margin of normal tissue. Further treatment depends mainly on the Breslow thickness of the lesion. Wide local excision may necessitate flap or graft closure of the wound. Occasionally, the pathologist will report incomplete excision of the melanoma, despite wide clinical margins. This means further surgery or radiotherapy will be recommended to ensure the tumour has been completely removed.

Figure 4. Superficial spreading melanoma

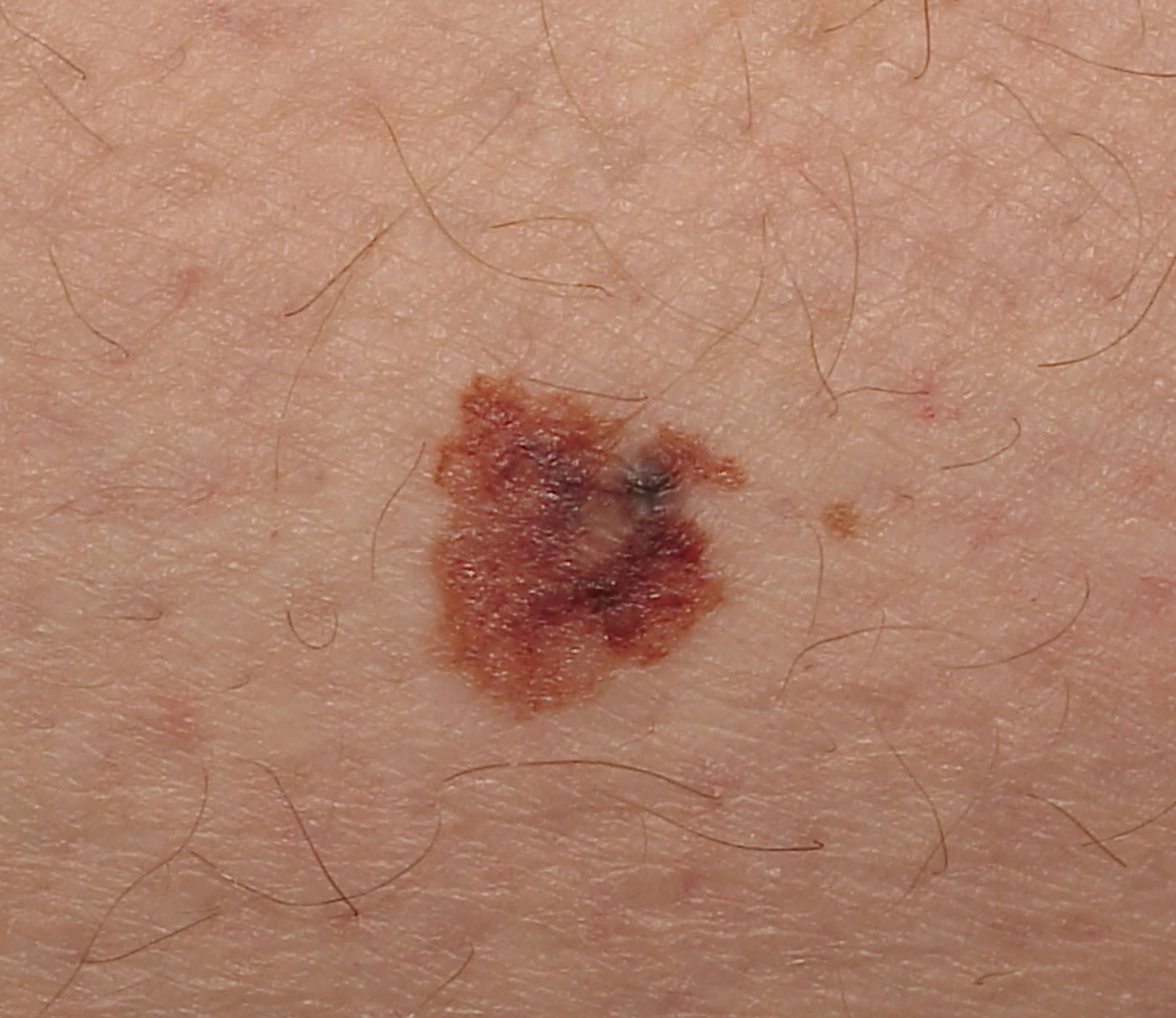

Nodular melanoma

Nodular melanomas are a faster-developing type of melanoma that can quickly grow downwards into the deeper layers of skin (vertical growth) if not removed. Nodular melanoma can penetrate deep within the skin within a few months of its first appearance. Nodular melanoma is the second most common growth pattern, comprising 10 to 15% of all cutaneous melanomas. Nodular melanomas usually appear as a changing lump (nodule) on the skin that might be black to red in color. Nodular melanomas often grow on previously normal skin and most commonly grow on the head and neck, chest or back.

Nodular melanoma may develop on any body surface area but most commonly is diagnosed on the trunk of men. Bleeding or oozing is a common symptom.

The main risk factors for nodular melanoma are:

- Increasing age

- Previous invasive melanoma or melanoma in situ

- Many melanocytic nevi (moles)

- Multiple (>5) atypical nevi (abnormal-looking moles)

- Fair skin that burns easily

It is less strongly associated with sun exposure than superficial spreading and lentigo maligna types of melanoma.

Nodular melanoma is thought to be biologically more aggressive than superficial spreading melanoma. Clinically, the lesion is dark and most often uniform in color. Histologically, nodular melanoma is notable for the complete absence of melanocytic abnormalities in the adjacent epidermis. Approximately 5% of nodular melanoma are amelanotic. Amelanotic nodular melanoma may have a symmetric appearance but occasionally becomes polypoid or cauliflower in appearance. nodular melanoma does not have a radial growth phase and is associated with rapid evolution to vertical growth and invasion of the dermis. For this reason, nodular melanomas tend to be thicker, more high-risk lesions.

The initial treatment of primary melanoma is to cut it out; the lesion should be completely excised with a 2-3 cm margin of normal tissue. Further treatment depends mainly on the Breslow thickness of the lesion.

After initial excision biopsy; the radial excision margins, measured clinically from the edge of the melanoma. This may necessitate a flap or graft to close the wound. Occasionally, the pathologist will report incomplete excision of the melanoma, despite wide margins. This means further surgery or radiotherapy will be recommended to ensure the tumor has been completely removed.

Figure 5. Nodular melanoma

Footnote: A dense, black, irregular lesion with multiple nodular areas and an irregular notched border (arrow)

[Source 7 ]Lentigo maligna melanoma

Lentigo maligna melanomas most commonly affect older people, particularly those who have spent a lot of time outdoors. Lentigo maligna melanoma constitutes approximately 10% of all melanomas, arises from lentigo maligna (melanotic freckle of Hutchinson or precancerous melanosis of Dubreuilh) 5. Lentigo maligna melanoma is found most commonly on sun-exposed skin such as the face in elderly individuals (median age, 70 years). Clinically, the lesions are generally large (3 to 4 cm in diameter) and flat with irregular borders, in variable shades of tan to dark brown. Hypopigmented areas in the lesion represent areas of regression. The precursor lesion, lentigo maligna, usually has been present for long periods (5 to 15 years) prior to the development of invasive melanoma.

To start with, lentigo maligna melanomas are flat and develop sideways in the surface layers of skin. Lentigo maligna melanomas look like a freckle, but they’re usually larger, darker and stand out more than a normal freckle. Lentigo maligna melanomas can gradually get bigger and may change shape. At a later stage, they may grow downwards into the deeper layers of skin and can form lumps (nodules).

Lentigo maligna melanoma should be completely removed surgically. If possible, there should be a 1 cm margin of normal skin around the tumor, but the margin may depend on the site of the lesion and how close it is to important structures like the mouth, eye or nose. If the local lymph nodes are enlarged due to melanoma, they should also be completely removed, which entails a major surgical procedure under general anaesthetic.

Figure 6. Lentigo maligna melanoma

Acral lentiginous melanoma

Acral lentiginous melanoma is a type of malignant melanoma originating on palms, soles of foot and under the nail (subungual melanoma). Acral lentiginous melanoma is a form of melanoma characterized by its site of origin: palm, sole, or beneath the nail (subungual melanoma). Acral lentiginous melanoma represents approximately 3 to 8% of all melanomas. Acral lentiginous melanoma does not represent the most common type of melanoma in any racial group in United States-based studies 8. Acral lentiginous melanoma is more common on feet than on hands. It can arise de novo in normal-appearing skin, or it can develop within an existing melanocytic nevus (mole). Acral lentiginous melanoma constitutes a substantially higher proportion of melanomas in dark-skinned individuals such as 70% of African Americans, 46% of Asians, and Hispanics. The majority of acral lentiginous melanoma lesions are tan to dark brown macule that are large (3 cm in diameter) with an irregular borders, but in advanced lesions it may be ulcerating or may present as a fungating mass. The majority arise in people over the age of 40 (median age, 59 years). Acral lentiginous melanoma is equally common in males and females. Subungual melanoma (melanoma beneath the nail) most commonly occurs on the great toe or thumb.

Although similar in clinical appearance to lentigo maligna melanoma, acral lentiginous melanoma is a biologically much more aggressive lesion, with a relatively short evolution to the vertical growth phase.

The cause or causes of acral lentiginous melanoma are unknown. It is not related to sun exposure.

Acral lentiginous melanoma starts as a slowly-enlarging flat patch of discolored skin. At first, the malignant cells remain within the tissue of origin, the epidermis — the in situ phase of melanoma, which can persist for months or years.

Acral lentiginous melanoma becomes invasive when the melanoma cells cross the basement membrane of the epidermis, and malignant cells enter the dermis. A rapidly-growing nodular melanoma can also arise within acral lentiginous melanoma and proliferate more deeply within the skin.

The initial treatment of primary melanoma is to cut it out; the lesion should be completely excised with a 2–3 mm margin of healthy tissue. Further treatment depends mainly on the Breslow thickness of the lesion. A flap or graft may be needed to close the wound. In the case of acral lentiginous and subungual melanoma, this may include partial amputation of a digit. Occasionally, the pathologist will report incomplete excision of the melanoma, despite wide margins requiring further surgery or radiotherapy to ensure the tumor has been completely removed.

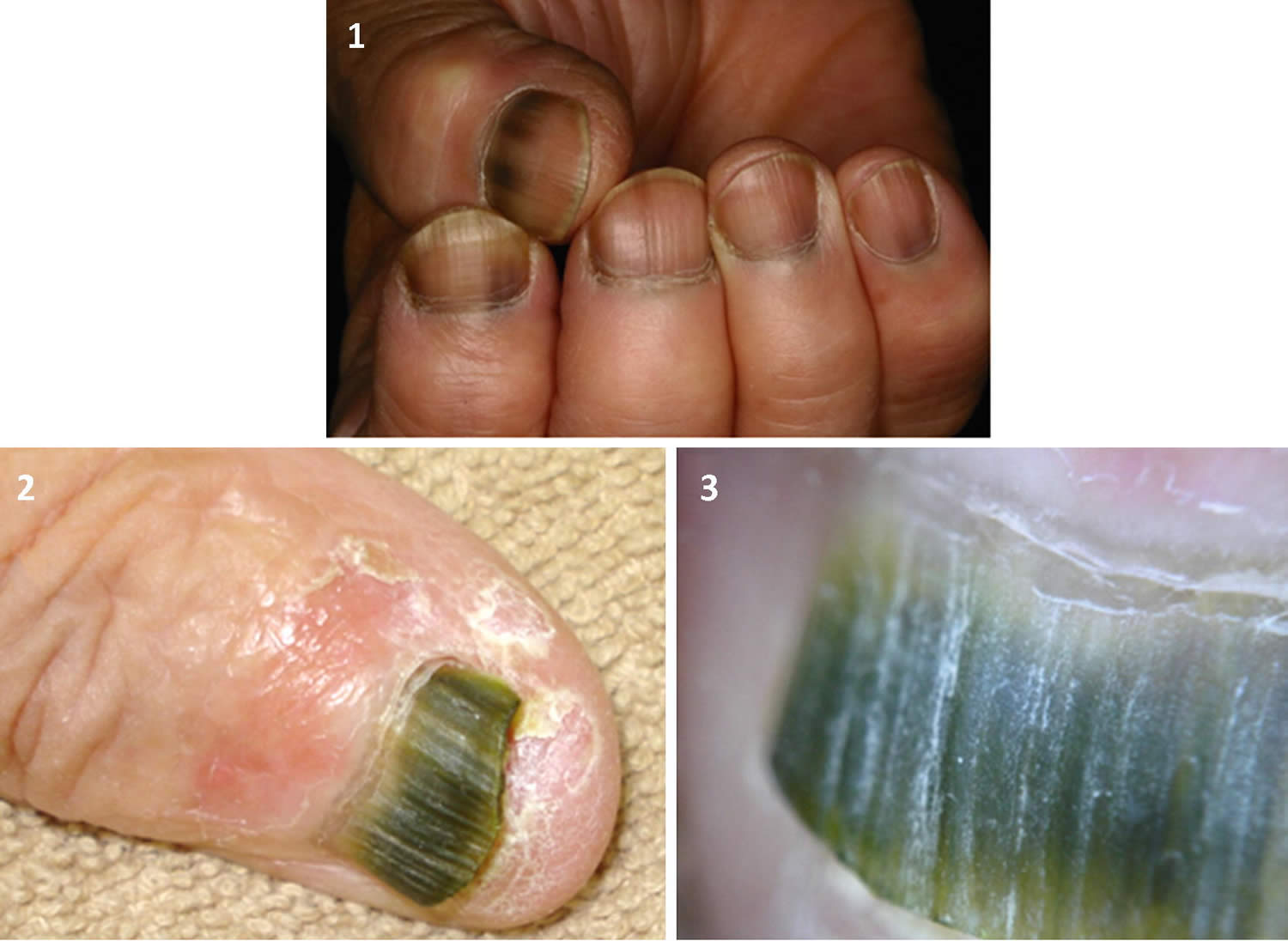

Figure 7. Acral lentiginous melanoma

Subungual melanoma

Subungual melanoma is a melanoma of the nail matrix (malignant proliferation of melanocytes in the nail matrix). Subungual melanoma is usually a variant of acral lentiginous melanoma. Typically, subungual melanoma presents clinically as a pigmented streak in the nail plate, which slowly expands at the proximal border and may extend to involve the adjacent nail fold (Hutchinson sign). Subungual melanoma is most often diagnosed in the 60 to 70-year-old age group.

Melanoma of the nail unit is rare. While occurring equally in all racial groups, it accounts for around 0.7–3.5% of malignant melanomas in white-skinned populations and up to 75% of dark-skinned and Asian populations.

Subungual melanoma is the most common type of melanoma diagnosed in deeply pigmented individuals, probably due to this population’s low incidence of cutaneous melanoma, due to the melanin pigment protection from ultraviolet (UV) radiation.

In contrast to cutaneous melanoma, melanoma of the nail does not appear to be related to sun exposure. Melanoma of the nail unit originates from activation and proliferation of melanin producing melanocytes of the nail matrix.

Injury or trauma may be a factor, accounting for the greater incidence in the big toe and thumb (75–90% of cases).

The management plan for melanoma of the nail unit will usually require a multidisciplinary melanoma team to direct further investigations and treatment. The mainstay of management of melanoma of any kind is excision.

Figure 8. Subungual melanoma

[Source 9 ]Amelanotic melanoma

Amelanotic melanomas is a form of melanoma in which the malignant cells have little or no color, but may occasionally be pink or red, or have light brown or grey edges. The term ‘amelanotic’ is often used to indicate lesions that are only partially devoid of pigment while truly amelanotic melanoma where lesions lack all pigment is rare 10.

Amelanotic melanoma accounts for approximately 1–8% of all melanomas. The incidence of truly amelanotic melanoma is difficult to estimate, given that many hypopigmented lesions are labelled as amelanotic 10.

Risk factors for developing amelanotic melanoma include 11:

- Increasing age — although amelanotic melanoma accounts for a significant proportion of melanoma in young children 12

- Sun-exposed skin — particularly in older people with chronic photodamage.

The melanoma cells in amelanotic melanoma cannot produce mature melanin granules, which results in lesions that lack pigment. To account for the lack of pigment, three models have been proposed 11:

- Amelanotic melanoma may be a poorly differentiated subtype of typical melanoma.

- Amelanotic melanoma may be a de-differentiated melanoma that has lost its normal phenotype.

- Amelanotic melanoma cells may retain their melanocytic identity but gain the ability to form different phenotypes (multipotency) 13.

Amelanotic melanoma is treated in the same way that a pigmented melanoma is treated.

The prognosis of amelanotic melanoma is similar to that of pigmented melanomas 11. Prognostic factors include the Breslow thickness of the melanoma at the time of excision (this is considered to be the most important factor), the location of the lesion, patient age, and sex. Importantly, because of their atypical clinical features, amelanotic melanomas may have a delay in their diagnosis and, consequently, are often more advanced than pigmented melanomas when diagnosed 14.

The risk of metastasis is directly related to the Breslow thickness, with thicker melanomas being more likely to metastasise. The 2008 Clinical practice guidelines for the management of melanoma in Australia and New Zealand report that metastases are rare for thin melanomas (< 0.75 mm), with the risk increasing to 5% for melanomas 0.75–1.00 mm thick. Melanomas thicker than 4.0 mm have a significantly higher risk of metastasis of 40% 15.

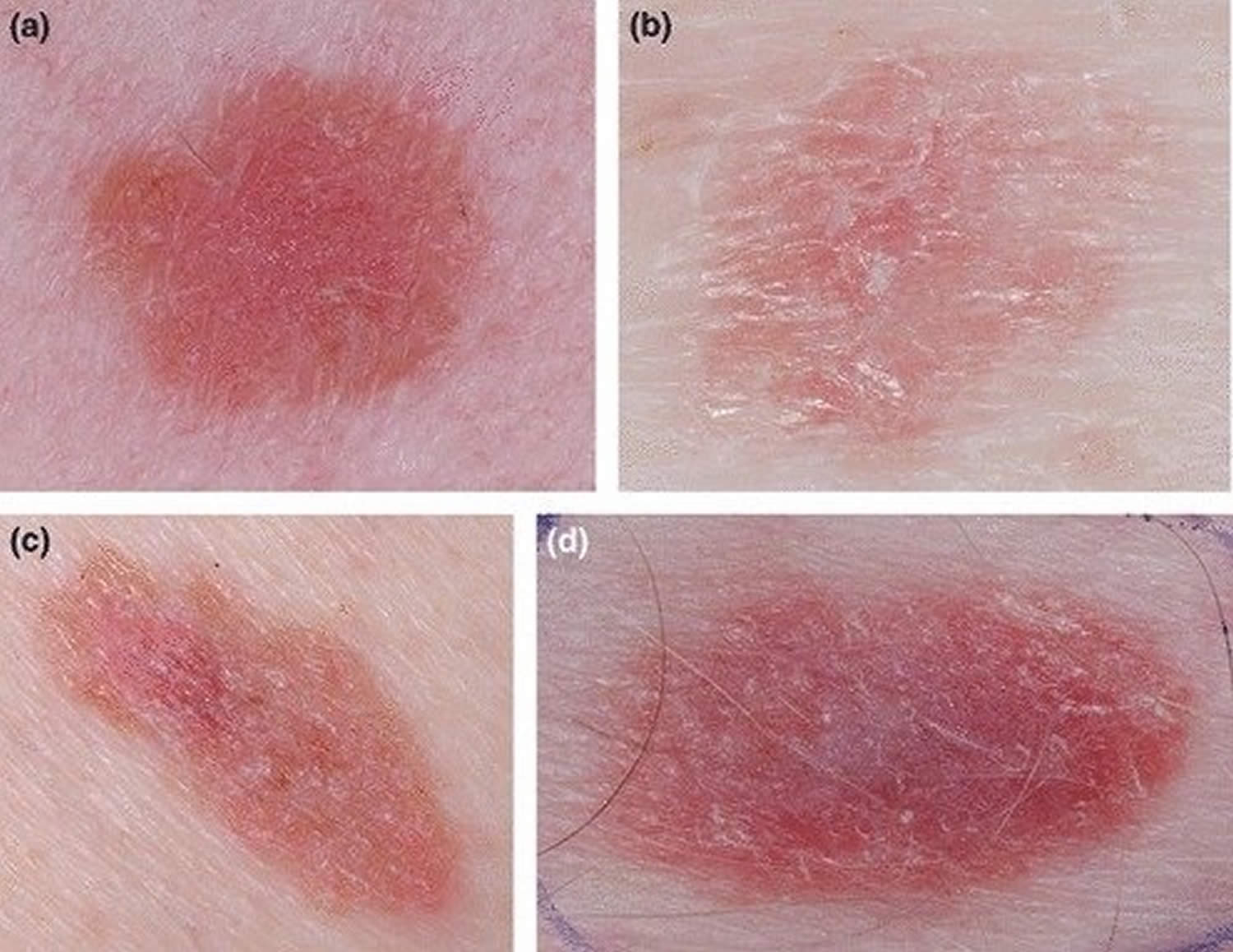

Figure 9. Amelanotic melanoma

Footnotes: Clinical characteristics of amelanotic melanomas that are not of the nodular subtype. (a, b) Scaly, erythematous macules and patches, with a relatively circular to oval (c, d) symmetric shape, regular border and disruption of skin markings.

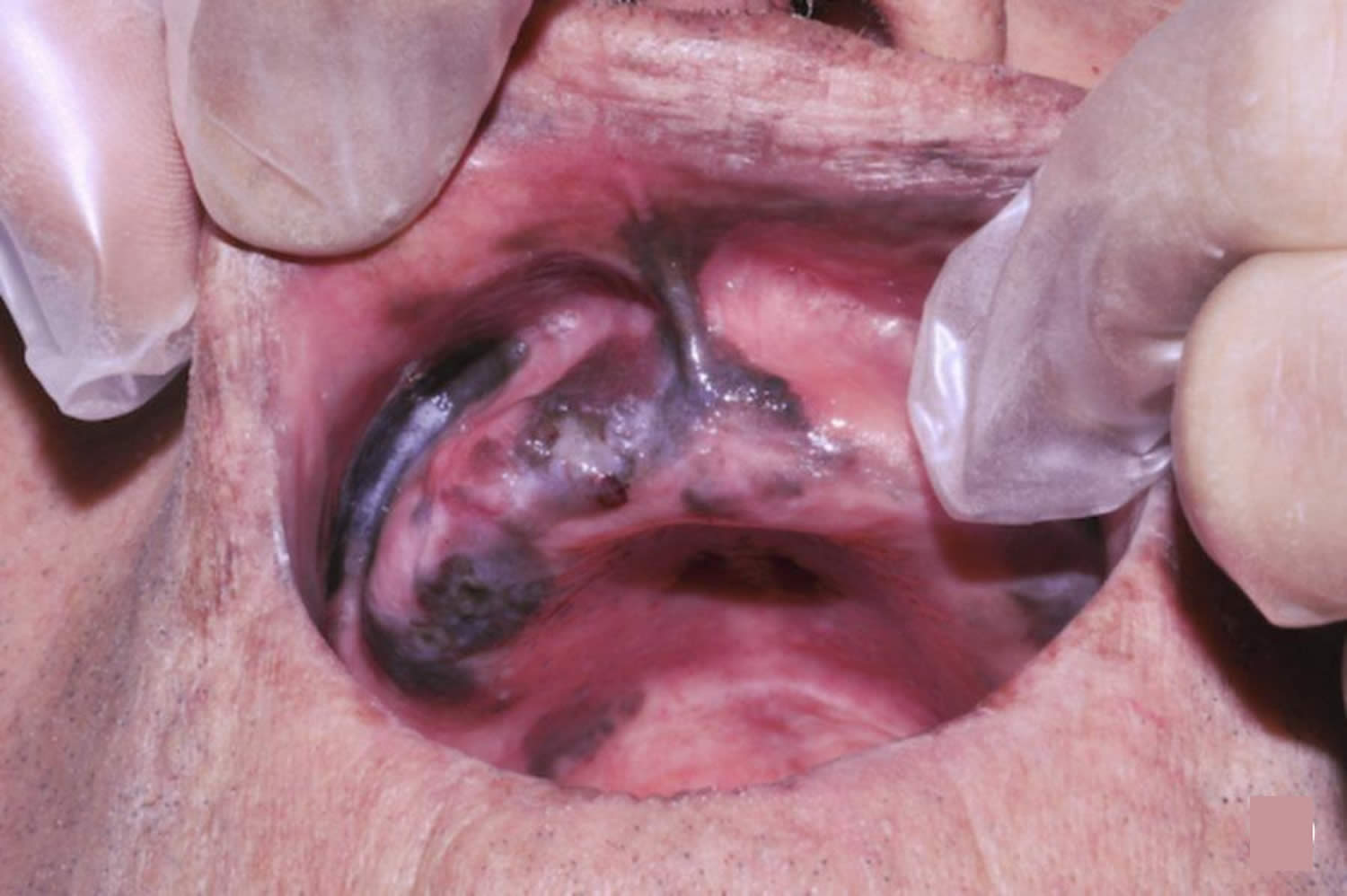

[Source 16 ]Mucosal melanoma

Melanoma usually develops in the skin and is called cutaneous melanoma (cutaneous means skin). But rarely, melanoma can start in the mucous membrane – this is the layer of tissue that covers the inside surface of parts of the body such as the mouth or vagina. Mucosal melanoma is a rare type of melanoma that occurs on mucosal surfaces. Mucous membranes are moist surfaces that line cavities within the body. This means that mucosal melanoma can be found in the respiratory tract, gastrointestinal tract or genitourinary tract. Mucosal melanomas have a poor prognosis, as most patients develop metastases despite aggressive therapy 17.

Mucosal melanomas are most often found in the head and neck, in the eyes, mouth, nasopharynx and larynx, but they can also arise throughout the gastrointestinal tract, anus and vagina. Mucosal melanoma makes up approximately 1.1% of all melanomas, but are usually more complicated because of late diagnosis due to their less visible locations and because they are often amelanotic – meaning they are not pigmented.

The peak age of diagnosis of mucosal melanoma is between 70 and 79. However, younger people have also been known to develop mucosal melanoma, especially of the oral cavity.

Mucosal melanoma of the genital tract is more common in females.

Subtypes of mucosal melanoma are based on the tissue in which they arise.

Possible places where mucosal melanoma can start include the:

- Respiratory tract

- Nasal cavity

- Paranasal sinuses

- Oral cavity

- Gastrointestinal tract

- Transitional zone of anal canal (the line where the normal skin meets the mucous membrane)

- Genitourinary tract

- Vulva

- Vagina

The signs and symptoms of mucosal melanoma largely depend on its location. Therefore, there are a wide variety of symptoms that patients may experience.

While there are many suggested risk factors for mucosal melanoma, there is only weak evidence for all, and none that are widely accepted. About 25% of mucosal melanomas have been linked with problems with a gene called KIT 17. Genes are the templates used for making protein, and mutations in the KIT gene cause the production of a mutant protein. The KIT gene can also be over-expressed, which means that there is more of the KIT protein being made than usual. Both the mutation and over-expression of the KIT gene have been associated with mucosal melanoma.

Possible risk factors include:

- Oral mucosal melanoma

- Smoking

- Ill-fitting dentures

- Ingested/inhaled environmental carcinogens

- Vulvar melanoma

- Chronic inflammatory disease

- Viral infections

- Chemical irritants

- Genetic factors

- Anorectal melanoma

- Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)

The best form of treatment for mucosal melanoma is wide local excision of the lesion. This may not always be possible, as the melanoma may be located on an important anatomical structure, or be too large to excise safely.

Due to the likelihood of the same melanoma recurring, surgical resection is often combined with radiotherapy. Radiotherapy is also a consideration for patients who are not suitable for surgery.

Figure 10. Mucosal melanoma of the buccal mucosa

Ocular melanoma

Ocular melanoma also called eye melanoma, uveal melanoma or choroid melanoma 18. Uveal melanoma starts in the uvea. The uvea is the middle layer of the eye and has 3 parts:

- Iris (the colored part)

- Ciliary body

- Choroid

Most uveal melanomas develop in the choroid part of the uvea (choroid melanoma).

Ocular melanoma accounts for about 3.7% of all melanomas 19. Primary ocular melanoma is the most common primary malignant tumor of the eye in adults 20. In the US incidence of ocular melanoma is 6 per million, compared with 153.5 for cutaneous melanoma 19. Incidences of uveal and conjunctival melanomas in the US are 4.9 and 0.4 per million, respectively 19. It is more common among men, with incidence of 6.8 per million, compared with 5.3 per million in women (male to female rate ratio 1.29) 19. In Australia ocular melanoma shows higher rates among men older than 65 years and among residents of rural areas, with incidence of 8 per million in men, and 6.1 per million in women 21.

Ocular melanoma rates are 8-10 times higher among whites compared with blacks, but although obvious this difference is less pronounced compared to cutaneous melanoma which shows 16 times higher rates among whites 19. In contrast to other ocular melanomas, conjunctival melanoma rates are 2.6 times higher in whites than in blacks, which is similar with that of mucosal melanomas 22.

Incidence of ocular melanoma is increasing with age, with a peak in seventh and eighth decade of life 19. In contrast to uveal melanoma which incidence has remained stable over last three decades 23, conjunctival melanoma has shown an increase in incidence, especially among white men and older than 60 years 24.

In its early stages, ocular melanoma may not cause any symptoms. Because most melanomas develop in the part of the eye you cannot see, you may not know that you have a melanoma.

When ocular melanoma symptoms do occur, they can include:

- a dark spot on the iris or conjunctiva

- blurred or distorted vision or a blind spot in your side vision

- the sensation of flashing lights

- a change in the shape of the pupil

The main indicators of ocular melanoma in 90 patients described in a Canadian study were 25:

- partial loss of visual field (in 33% of patients)

- sun sensitivity (in 20%)

- blurred vision (in 20%)

- incidental finding on eye examination (in 17%)

Conjunctival melanoma presents as an increasingly irregular pigmented lesion on the external eye. Other symptoms may include a protruding eye, change in colour of the iris, red or painful eye, and retinal detachment.

It is not clear why eye melanomas develop. Scientists do know that people born with certain growths in or on the eye (nevi or moles), as well as those with lighter colored eyes, are at a greater risk for developing ocular melanoma.

Ocular melanoma occurs when the DNA of the pigment cells of the eye develop errors. These errors cause the cells to multiply out of control. The mutated cells collect in or on the eye and form a melanoma.

Certain factors increase your risk for developing melanoma. These include:

- exposure to natural sunlight or artificial sunlight (such as from tanning beds) over long periods of time may cause a melanoma on the surface of the eye (conjunctival melanoma)

- having light-colored eyes (blue or green eyes)

- older age

- Caucasian descent

- having certain inherited skin conditions, such as dysplastic nevus syndrome, which cause abnormal moles

- having abnormal skin pigmentation involving the eyelids and increased pigmentation on the uvea; and

- having a mole in the eye or on the eye’s surface

Because ocular melanoma may not cause any symptoms at first, the disease is often detected during a routine eye exam.

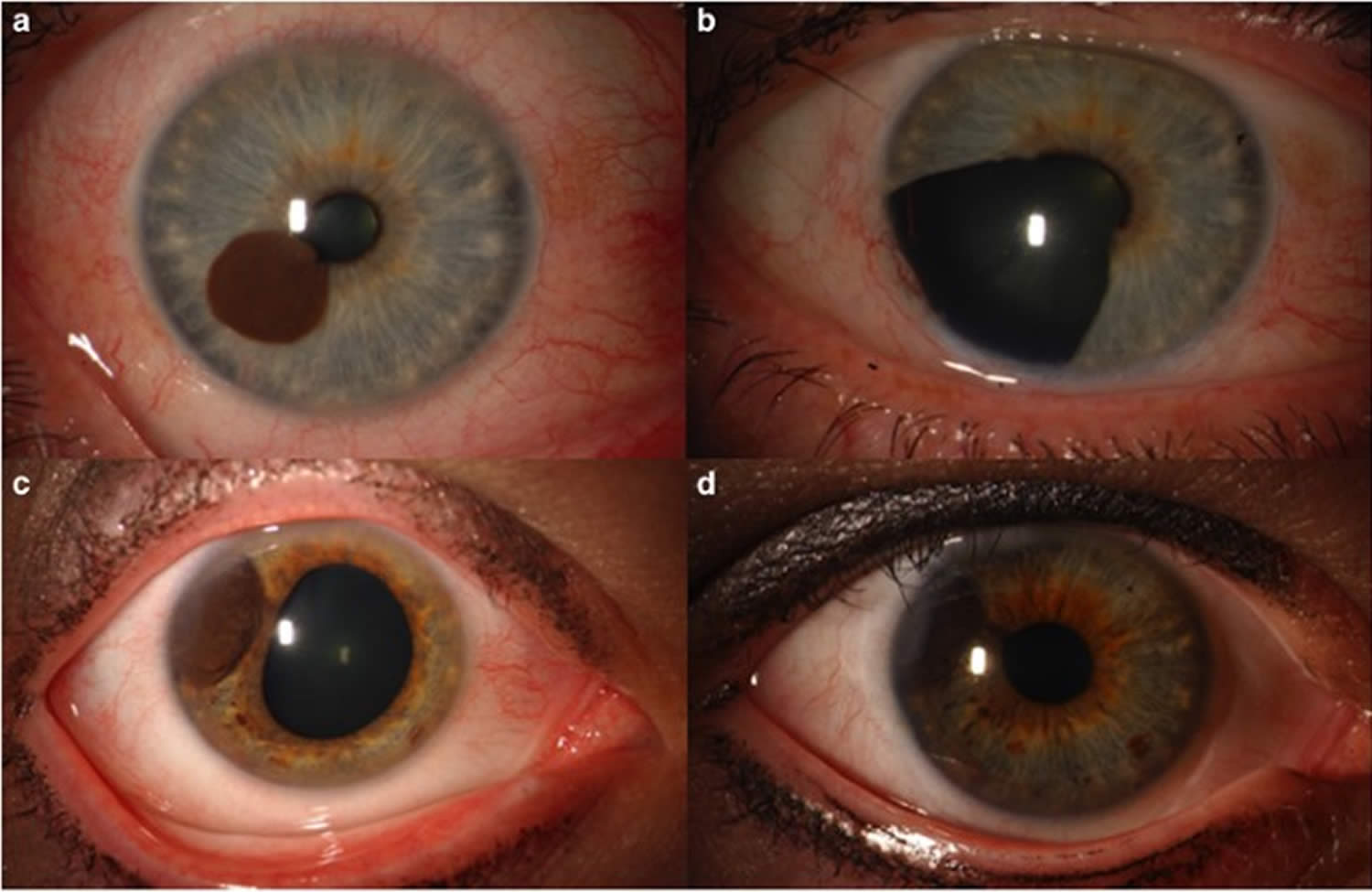

Figure 11. Ocular melanoma (iris melanoma)

Footnote: (a) Iris melanoma in the mid-zone of iris (b) treated by iridectomy. (c) Iris melanoma at the root of iris and (d) treated with iodine-125 plaque radiotherapy.

[Source 26 ]If your ophthalmologist suspects that you have ocular melanoma, he or she may recommend more tests. These may include:

- Ultrasound examination of the eye. An ultrasound examination of the eye is a procedure in which high-energy sound waves (ultrasound) are bounced off the internal tissues of the eye to make echoes. Eye drops are used to numb the eye and a small probe that sends and receives sound waves is placed gently on the surface of the eye. The echoes make a picture of the inside of the eye. The resulting image allows the ophthalmologist to measure the size of the melanoma.

- Fluorescein angiography. This procedure uses a dye injected into your arm, which travels into your eye. A special camera then takes pictures of the inside of your eye to see if there is any blockage or leakage.

- Fundus autofluorescence. This test uses a special kind of camera that makes areas of damage reveal themselves as small points of light in a photograph.

- Optical coherence tomography also known as OCT, this imaging test takes highly detailed pictures of the inside of your eye.

- Biopsy. If your ophthalmologist thinks you have a conjunctival melanoma, he or she may perform a biopsy. This is when the growth is removed from the surface of the eye. The tissue is then tested and examined in a laboratory. Biopsies are not usually needed to diagnose ocular melanoma, but may reveal information about the tumor and if it might spread to other parts of the body.

Your ophthalmologist may refer you to another specialist to do more tests to determine whether the melanoma has spread (metastasized). These tests may need to be repeated regularly for many years.

If you are diagnosed with ocular melanoma, your treatment options will vary. Treatment depends on:

- the location and size of the melanoma

- and your general health

Generally, treatment options fall into two categories: radiation and surgery.

- Ocular melanoma radiation. In radiation therapy, various types of radiation are used to kill the melanoma or keep it from growing. The most common type of radiation therapy used for ocular melanoma is called plaque radiation therapy. Radioactive seeds are attached to a disk, called a plaque, and placed directly on the wall of the eye next to the tumor. The plaque, which looks like a tiny bottle cap, is often made of gold. This helps protect nearby tissues from damage from the radiation directed at the tumor. Temporary stitches hold the plaque in place for four or five days, before it is removed. Radiation therapy can also be delivered by a machine. This machine directs a fine beam of radioactive particles to your eye. This type of radiation therapy is often done over the course of several days. For smaller tumors, laser, heat energy, or both may be used for treatment.

- Ocular melanoma surgery. Depending on the size and location of the melanoma, surgery may be recommended. The surgery may involve removing the tumor and some of the healthy tissue of the eye surrounding it. For larger tumors, tumors that cause eye pain, and for tumors involving the optic nerve, the surgery may involve removing the entire eye (enucleation). After the eye is removed, an implant is put in its place and attached to the eye muscles, so that the implant can move. Once you are healed from the surgery, you will be fitted with an artificial eye (prosthesis). It will be custom painted to match your existing eye.

- Both radiation and surgery can damage the vision in your eye.

Conjunctival melanoma treatment

For melanoma on the surface of the eye, treatment can include chemotherapy eye drops, surgery, freezing treatment, and radiation.

You should talk to your ophthalmologist about how treatment may affect your vision. He or she can also explain the options available to you to help with any vision loss.

Unfortunately metastatic melanoma remains the leading cause of death among patients with ocular melanoma. The extent of systemic spread and tumor burden determines the average length of survival after liver metastases have been detected. Metastatic disease was diagnosed at a 25% and 34% rate at 5-years and 10-years respectively in the Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study (COMS) with the liver affected 89% of the time. The mortality rate after diagnosis of metastatic disease was 80% at 1 year and 92% at 2 years 27.

Desmoplastic melanoma

Desmoplastic melanoma is a rare type of invasive melanoma accounting for about 0.4% to 4% of all melanomas 28, 29. Desmoplastic melanoma can develop anywhere on your body but it’s most common in the head and neck area. It’s often the same color as your skin and can look like a scar. Desmoplastic melanoma is more common in men than women, with a male to female ratio of approximately 1.7-2 to 1 30. Mean age at diagnosis is 66 to 69 years, which is considerably older than that described for nondesmoplastic melanoma (approximately 60 years) 31.

- Desmoplastic melanoma often involves nerve fibers, when it is called neurotropic melanoma.

- The malignant cells within the dermis are surrounded by fibrous tissue.

- Desmoplastic melanoma sometimes arises underneath a lentigo maligna, a type of melanoma in situ.

The main risk factors for desmoplastic melanoma are 32:

- Increasing age

- Previous invasive melanoma or melanoma in situ

- Fair skin that burns easily

- Sun damaged skin.

Desmoplastic melanoma tends to occur in areas of chronic sun exposure. The most common location is the head and neck (50% of cases), followed by the trunk (20%-25%) and extremities (20%-25%) 33. Desmoplastic melanoma can, however, arise in areas not chronically exposed to the sun, such as mucous membranes 34 and acral sites 35.

Desmoplastic melanoma usually presents as a firm, nonpigmented papule or plaque with poorly defined borders in sun-damaged skin. Malignant melanoma is suspected initially in just 27% of cases 36. Clinically, desmoplastic melanoma is often confused with a benign skin lesion, such as scar tissue, dermatofibroma, neurofibroma, and intradermal melanocytic nevus, or with a malignant nonmelanocytic skin tumor such as basal cell carcinoma and squamous carcinoma.

There are also clinical differences between pure and mixed desmoplastic melanomas 37. An epidermal component in the form of lentigo maligna, lentigo maligna melanoma or superficial spreading melanoma appears to be present in 80% to 100% of mixed desmoplastic melanomas 33. Lesions suspicious for lentigo maligna melanoma should therefore be palpated to check for a firm subcutaneous nodule indicative of desmoplastic melanoma 33.

Figure 12. Desmoplastic melanoma

Footnote: Clinical image of a desmoplastic melanoma in a 53-year-old woman who presented with a firm, pink interscapular tumor initially thought to be a keloid lesion. Biopsy showed a pure desmoplastic melanoma with a thickness of 8.5 mm.

[Source 33 ]It is essential to diagnose desmoplastic melanoma accurately. A careful clinical history is important, which includes noting previous treatments received for non-resolving lesions. Palpation is an important step, as a large majority of desmoplastic melanoma are indurated. Clinical diagnosis is aided by dermoscopy and skin biopsy (usually excision biopsy). Depending on the thickness and proportion of desmoplasia within the invasive melanoma, sentinel lymph node biopsy, imaging studies and blood tests may be advised.

As desmoplastic melanoma is commonly found on the head and neck, and with lentigo maligna, it is possible that if such lesions are only partially biopsied, the desmoplastic melanoma may be missed. Reflectance confocal microscopy may be useful to help guide the site of the biopsy.

Dermoscopy can be helpful in distinguishing desmoplastic melanoma from other skin lesions. The most frequently observed dermatoscopic features of desmoplastic melanoma are:

- Melanocytic features in about 50% (pigmented globules or network)

- Asymmetrical structure and colours

- Regression features: scar-like areas, grey dots

- Multiple colours

- Atypical or polymorphous vascular pattern

- Crystalline structures.

If the skin lesion is suspicious of desmoplastic melanoma, it should be urgently cut out (excision biopsy).

The pathological diagnosis of melanoma can be very difficult. Histopathological features of desmoplastic melanoma include:

- A paucicellular atypical spindle cell proliferation, separated by fibrocollagenous stroma within the dermis or subcutaneous fat.

- There is overlying melanoma in-situ, typically of lentigo maligna type, in approximately 75% of cases.

- Nerve infiltration or neurotropism is found in about half of desmoplastic melanomas.

- Lymphocytic nodular aggregates may be seen in association with desmoplastic melanoma, but are not diagnostic.

Desmoplastic melanoma is categorized into either ‘pure’ or ‘mixed’ subtypes, which reflect the extent of desmoplasia. The mixed subtypes include a component of spindle cell melanoma.

- Pure subtype: ≥ 90% desmoplasia

- Mixed subtype: < 90% desmoplasia

Immunohistochemical stains for melanoma may be helpful.

- S100 and Sox 10 are usually positive.

- HMB-45 and Melan-A are usually negative.

- p75 nerve growth factor is a marker for spindle cell melanoma.

The initial treatment of a desmoplastic melanoma is surgical excision 32.

- For pure desmoplastic melanoma, a 2 cm margin of normal tissue may be recommended, whatever its thickness.

- For mixed desmoplastic melanoma, margins follow guidelines for other forms of invasive melanoma (1–2 cm, depending on Breslow thickness).

Adjuvant radiation therapy may be considered for pure desmoplastic melanoma, Breslow thickness > 4 mm, perineural invasion or positive surgical margins.

Current evidence suggests that desmoplastic melanoma behaves differently to conventional melanoma 38, 39. Desmoplastic melanoma appears to be associated with a higher risk of local recurrence and a lower rate of lymph node metastasis 40. The risk of lymph node involvement seems to be lower than in non-desmoplastic melanomas of a similar thickness; variable rates have been reported for sentinel lymph node involvement (0% to 18.2% depending on the series) 38. It is difficult to accurately predict the prognosis of desmoplastic melanoma, as conflicting data have been reported and many studies do not distinguish between pure and mixed variants. Most recent studies, however, have not found significant differences in survival between patients with desmoplastic melanomas and non-desmoplastic melanomas of a similar thickness 38, 39, 41. The impression that pure desmoplastic melanoma is less likely than mixed desmoplastic melanoma to spread to distant sites and therefore has better survival rates has not been consistently demonstrated. Maurichi et al. 41 observed significant differences in overall survival between patients with mixed and pure desmoplastic melanoma (61.3% vs. 79.5%), but their findings have not been corroborated by subsequent studies 42, 43. Distant metastases, which are mostly located in the lung, have been linked to previous recurrences and deep lesions 44.

Most studies have shown that desmoplastic melanoma has a high risk of local recurrence (approximately 10%-14%), particularly in the case of mixed desmoplastic melanomas 41, 45, 46. Some authors have attributed the more local aggressive nature of pure desmoplastic melanoma to its later diagnosis (it is a rare tumor with an atypical presentation) and to the high frequency of perineural invasion and inadequate surgical margins 36.

A number of factors might explain the more aggressive behavior of desmoplastic melanoma. Shi et al. 40, in a retrospective study of 3657 desmoplastic melanoma cases, found that male sex and an age of older than 68 years were independent predictors of worse overall and disease-free survival. Although these findings have some support in the literature, other authors have not detected any differences in disease-free survival 47. Perineural invasion has also been proposed as a poor prognostic factor in desmoplastic melanoma 48 and has been seen to significantly correlate with greater Breslow thickness 36.

There are conflicting reports about prognostic indicators and outcomes for desmoplastic melanoma, due to its rarity, differences in pathological interpretation, and differing study designs/methodology. The results of the three studies are described below.

- 5-year overall survival rates were better for 280 patients with localised desmoplastic melanoma (90%, median Breslow thickness 2.5 mm) compared to 7767 patients with non-desmoplastic melanoma (82%, median Breslow thickness 1.6 mm).

- A study of 1129 desmoplastic melanoma patients in the United States (1992–2007) reported a 5-year specific survival rate of 85% and 10-year survival of 80%. Older age, anatomic site of the head and neck and tumour thickness > 2 mm, ulceration, lymph node involvement and non-receipt of surgery were associated with lower survival.

- A study of 1,735 desmoplastic melanoma patients, also in the United States (1988–2006), reported overall survival at five years to be 65% and that wide local excision was associated with increased survival. Traditional prognostic factors such as Breslow thickness, nodal positivity, and ulceration did not predict survival in this group of patients.

Spindle cell melanoma

Spindle cell melanoma is a rare histological variant of malignant melanoma, characterized by the presence of spindle-shaped melanocytes arranged in sheets and fascicles 49. The diagnosis of spindle cell melanoma is challenging, as spindle cell melanoma may occur anywhere on the body and frequently mimics amelanotic lesions, including scarring and inflammation 50. On microscopy, it is often mistaken for other skin and soft tissue cancers with spindle cell morphologies 51. Desmoplastic melanoma is a variant of spindle cell melanoma where there are varying proportions of spindle cells and desmoplastic cells present in the histology. The actual incidence of spindle cell melanoma is unknown. Studies have suggested that between 1% and 14% of melanomas are of the spindle cell variant (including desmoplastic melanoma) 52.

Spindle cell melanomas more commonly occur in Caucasian men, affecting men and women at a ratio of 1.6:1–1.9:1 respectively. The average age at diagnosis is 50–80 years 53.

Spindle cell melanoma frequently presents as a non-specific amelanotic (non-pigmented) nodule on the patient’s trunk, head, or neck 54. Spindle cell melanoma may also first present as widespread melanoma metastases. Delays in diagnosis can occur due to its non-specific features and atypical presentation histologically 51.

Immunohistochemistry is a helpful tool in distinguishing spindle cell melanoma from other sarcomas and carcinomas 55. However, diagnosis remains a challenge as a number of sarcomas share some morphological and immunohistochemical features with spindle cell melanoma 56. Differentiation of spindle cell melanoma from desmoplastic melanoma is difficult because both melanomas are characterized by atypical, spindled, malignant melanocytes. However, the size of spindle cell collagen areas and the immunohistochemical markers, S100, MelanA and Tyrosinase, allow differential diagnosis 54. Therefore, the integration of clinical and histological assessment is essential for the diagnosis of spindle cell melanoma 57. Diagnosis of spindle cell melanoma is often delayed until patients exhibit advanced-stage disease, typically with widespread metastasis and poor treatment outcomes 58.

The treatment for spindle cell melanoma is similar to that for other forms of melanoma. Surgical excision is the first step in management 51.

Although the tendency for nodal involvement is low, the majority of spindle cell melanomas present with advanced disease, with a worse prognosis being seen in Caucasian men aged over 66 years 54.

Advanced disease with nodal and distal metastasis is associated with worse outcomes in spindle cell melanoma, as are higher grades of tumours, which have been associated with poorer disease-specific survival and overall survival 51.

Figure 13. Spindle cell melanoma

Spitzoid melanoma

Spitzoid melanoma is a malignant melanoma that is histologically similar to a benign skin lesion, Spitz nevus. Spitzoid melanoma presents as a changing and enlarging papule or nodule. It can be amelanotic (nonpigmented, red) or pigmented (brown, black or blue). Advanced Spitzoid melanoma may be crusted and ulcerated. It is most often located on the head or extremities.

Spitzoid melanoma is often round in shape and uniform in color. Therefore, it does not follow the commonly used ABCDE criteria of melanoma (Asymmetry, Border irregularity, Color variation, Diameter over 6 mm in greatest dimension) 59. Spitzoid melanoma can arise de novo (a new lesion), or within an existing Spitz nevus 60.

When the histological diagnosis is uncertain, the diagnosis of Spitzoid Melanoma of Uncertain Malignant Potential (STUMP) may be made.

Spitzoid melanomas are more common in adults than in children, but due to a very low rate of other cutaneous melanoma subtypes in children, the incidence of spitzoid melanomas is relatively high in children 60.

Spitzoid melanomas can occur in any ethnic group and on any body location 61.

Spitzoid melanoma is diagnosed on skin biopsy of an enlarging nodule.

Spitzoid melanoma should be completely excised with a margin of normal tissue 62. The recommended clinical margins depend on the measured thickness of the tumor, as with other melanomas. The specimen should be carefully examined under the microscope.

In thicker tumors, a sentinel lymph node biopsy may be recommended to determine whether the melanoma has spread. The role of sentinel lymph node biopsy biopsy is controversial in the management of atypical spitzoid melanocytic lesions and the reliability of any associated prognostic information unclear. Patients with spitzoid melanoma and positive sentinel lymph node biopsy have been shown to have a more indolent disease course than those with positive sentinel lymph node biopsy and non-spitzoid melanomas.

The prognosis of spitzoid melanoma in adults is similar to other melanomas of comparable thickness 61. In a study comparing ages of patients with spitzoid melanoma, it was found that there was an 88% 5-year survival rate in children (ages 0–10) with metastatic spitzoid melanoma, compared to a lower, 49% 5-year survival in children aged 11–17 years 63. The prognosis of children with spitzoid melanomas is better than that observed in adults 64.

Figure 14. Spitzoid melanoma

Footnotes: (a) Clinically, hypomelanotic rapid growing tumor on a 14 year old girl. (b) Dermoscopy: Polymorphic vascular pattern, with dotted vessels, milky red areas and remnants of pigment at the periphery, central shiny white structures. Spitzoid melanoma, Breslow 1.9 mm. (c) Clinically, amelanotic pink bump on the lower limb of a 3 year old girl. (d) Dermoscopy: Polymorphic vascular pattern, milky red areas and globules and shiny white structures. Spitzoid melanoma Breslow 5.5 mm. (e) Clinically ulcerated amelanotic bump on the lower limb of a 17 year old girl. (f) Dermoscopy: Vascular pattern showing dotted vessels and milky red globules, and ulceration. Spitzoid melanoma, Breslow 1.9 mm.

[Source 65 ]Melanoma signs and symptoms

Melanomas can develop anywhere on your body. Melanoma skin cancer most often develops in areas that have had exposure to the sun, such as your back, legs, arms and face. Melanomas can also occur in areas that don’t receive much sun exposure, such as the soles of your feet, palms of your hands and fingernail beds. These hidden melanomas are more common in people with darker skin.

The first melanoma signs and symptoms often are:

- A change in an existing mole

- The development of a new pigmented or unusual-looking growth on your skin. See your doctor as soon as possible if you notice changes in a mole, freckle or patch of skin, particularly if the changes happen over a few weeks or months.

- Melanoma doesn’t always begin as a mole. It can also occur on otherwise normal-appearing skin.

Melanoma can appear anywhere on your body, but they most commonly appear on the back in men and on the legs in women.

Melanoma can also develop underneath a nail, on the sole of the foot, in the mouth or in the genital area, but these types of melanoma are rare.

- Melanomas are uncommon in areas that are protected from sun exposure, such as the buttocks and the scalp.

- In most cases, melanomas have an irregular shape and are more than 1 color.

- The mole may also be larger than normal and can sometimes be itchy or bleed.

- Look out for a mole that gradually changes shape, size or color.

Melanoma found at typical skin sites arises as melanoma in situ, superficial spreading melanoma, or nodular melanoma. Lentigo maligna (and lentigo maligna melanoma) is predominantly a skin cancer of the head and neck, occasionally affecting the trunk and limbs.

Superficial (thin) forms of melanoma initially spread out within the epidermis. If all the melanoma cells are confined to the epidermis it is termed a melanoma in situ. When the cancerous cells have grown through the basement membrane and into the dermis it is known as invasive melanoma and is termed a superficial spreading melanoma. Superficial spreading melanoma is the most common type of invasive melanoma and accounts for over 50% of all melanoma. Nodular melanoma, presenting as a firm papule, nodule or plaque accounts for 20-25% of cases of melanoma and is the most aggressive type, it is more common in males and often presents in the fifth or sixth decade, but can occur at any age.

To help you identify characteristics of unusual moles that may indicate melanomas or other skin cancers, think of the letters ABCDE. The ABCDE checklist can be used to check for the main warning signs of melanoma:

- A is for asymmetrical shape. Look for moles with irregular shapes, such as two very different-looking halves. Melanomas usually have 2 very different halves and are an irregular shape

- B is for irregular border. Look for moles with irregular, notched or scalloped borders — characteristics of melanomas. Melanoma often has an irregular appearance, however, if a symmetrical lesion continues to grow out of proportion to the patient’s other moles, especially if aged > 45, then melanoma must be considered

- C is for changes in color. Look for growths that have many colors (a mix of 2 or more colors) or an uneven distribution of color.

- D is for diameter. Look for new growth in a mole larger than 1/4 inch (about 6 millimeters).

- Melanoma grow at different rates – even if the lesion is not changing, if it looks suspicious or if you notice any skin changes that seem unusual make an appointment with your doctor.

- E is for evolving. Look for changes over time, such as a mole that grows in size or that changes color or shape. Moles may also evolve to develop new signs and symptoms, such as new itchiness or bleeding.

It is also important to note that cancerous (malignant) moles vary greatly in appearance. Some may show all of the changes listed above, while others may have only one or two unusual characteristics.

Nodular melanoma can be brown, black, blue-black, and up to 50% are hypomelanotic (pink-red or skin-colored). The surface can be smooth, rough, or crusted. Nodular melanoma often lacks dermoscopic clues, and the diagnosis should be considered in any skin lesion demonstrating all of EFG:

- E = Elevation, and

- F = Firmness to touch, and

- G = Growth. Persistent growth for over one month

Hidden melanomas

Melanomas can also develop in areas of your body that have little or no exposure to the sun, such as the spaces between your toes and on your palms, soles, scalp or genitals 66. These are sometimes referred to as hidden melanomas because they occur in places most people wouldn’t think to check. When melanoma occurs in people with darker skin, it’s more likely to occur in a hidden area.

Hidden melanomas include:

- Melanoma under a nail also known as acral-lentiginous melanoma, is a rare form of melanoma that can occur under a fingernail or toenail. It can also be found on the palms of the hands or the soles of the feet. It’s more common in people of Asian descent, black people and in others with dark skin pigment.

- Melanoma in the mouth, digestive tract, urinary tract or vagina. Mucosal melanoma develops in the mucous membrane that lines the nose, mouth, esophagus, anus, urinary tract and vagina. Mucosal melanomas are especially difficult to detect because they can easily be mistaken for other far more common conditions.

- Melanoma in the eye also known as ocular melanoma. Ocular melanoma most often occurs in the uvea — the layer beneath the white of the eye (sclera). The most common type of ocular melanoma is uveal or choroidal melanoma, which grows at the back of the eye. Very rarely, it can grow on the thin layer of tissue that covers the front of the eye (the conjunctiva) or in the colored part of the eye (the iris). Noticing a dark spot or changes in vision can be signs of eye melanoma, although it’s more likely to be diagnosed during a routine eye examination.

The following should be considered as an urgent referral (2-week wait) for possible melanoma 7:

- Lips – irregular shape, atypical color (black, or > one color / shade of color), a firm papule/nodule

- Oral / genital – any new or changing pigmented lesion. Have a low threshold for referral as an accurate history is usually absent (check local guidelines for where to refer)

Melanoma causes

Melanoma occurs when something goes wrong in the melanin-producing cells (melanocytes) that give color to your skin.

Normally, skin cells develop in a controlled and orderly way — healthy new cells push older cells toward your skin’s surface, where they die and eventually fall off. But when some cells develop DNA damage, new cells may begin to grow out of control and can eventually form a mass of cancerous cells. DNA is the chemical in each of your cells that makes up your genes, which control how your cells function. You usually look like your parents because they are the source of your DNA. But DNA affects more than just how you look.

Some genes control when your cells grow, divide into new cells, and die:

- Genes that help cells grow, divide, and stay alive are called oncogenes.

- Genes that keep cell growth in check, repair mistakes in DNA, or cause cells to die at the right time are called tumor suppressor genes.

Cancers can be caused by DNA mutations (or other types of changes) that keep oncogenes turned on, or that turn off tumor suppressor genes. These types of gene changes can lead to cells growing out of control. Changes in several different genes are usually needed for a cell to become a cancer cell.

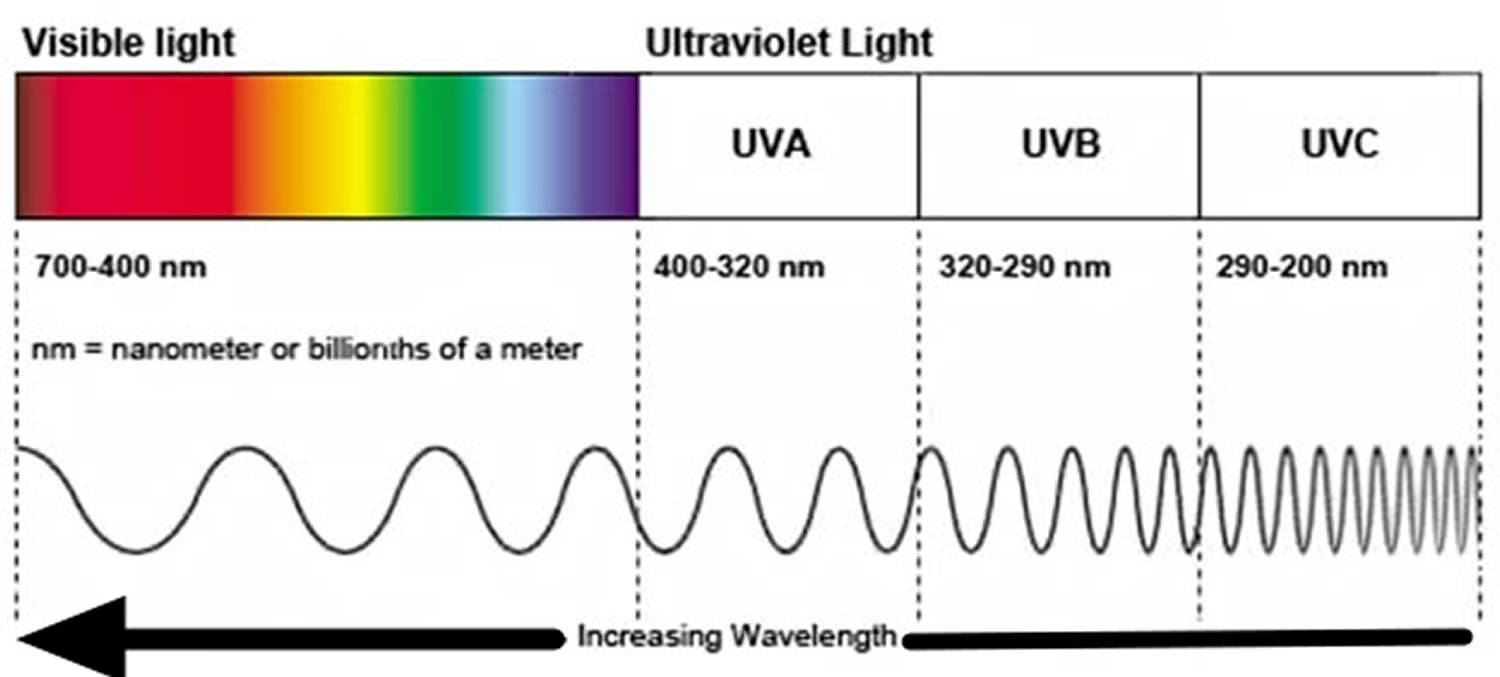

Just what damages DNA in skin cells and how this leads to melanoma isn’t clear. It’s likely that a combination of factors, including environmental and genetic factors, causes melanoma. Still, doctors believe exposure to ultraviolet (UV) radiation from the sun and from tanning lamps and beds is the leading cause of melanoma.

Ultraviolet radiation (UVR) is a major carcinogen. It damages the skin by producing reactive oxygen species (free radicals) that damage proteins, lipids, RNA and DNA. According to the two-hit model, where cancer is a result of accumulation mutations to the DNA, the development of skin cancer depends on an individual’s genetic makeup (particularly their MC1R signalling polymorphisms — that determine skin and hair color and sun sensitivity) plus two factors.

- Ultraviolet radiation (UVR) causes tumor initiation through mutations in DNA.

- Ultraviolet radiation (UVR) is a tumor promoter and causes progressive tumor growth.

UV light doesn’t cause all melanomas, especially those that occur in places on your body that don’t receive exposure to sunlight. This indicates that other factors may contribute to your risk of melanoma. These melanomas often have different gene changes than those in melanomas that develop in sun-exposed areas, such as changes in the C-KIT (or just KIT) gene.

The most common change in melanoma cells is a mutation in the BRAF oncogene, which is found in about half of all melanomas. Other genes that can be affected in melanoma include NRAS, CDKN2A, and NF1. Usually only one of these genes is affected 67.

Less often, people inherit gene changes from a parent that clearly raise their risk of melanoma. Familial (inherited) melanomas most often have changes in tumor suppressor genes such as CDKN2A (also known as p16) or CDK4 that prevent them from doing their normal job of controlling cell growth. This could eventually lead to cancer 67.

Some people, such as those with xeroderma pigmentosum (XP), inherit a change in one of the XP (ERCC) genes, which normally help to repair damaged DNA inside the cell. Changes in one of these genes can lead to skin cells that have trouble repairing DNA damaged by UV rays, so these people are more likely to develop melanoma, especially on sun-exposed parts of the body.

Melanoma skin cancer risk factors

A risk factor is anything that raises your risk of getting a disease such as cancer. Many risk factors for melanoma have been found, but it’s not always clear exactly how they might cause cancer.

Factors that may increase your risk of melanoma include:

- Fair skin. Having less pigment (melanin) in your skin means you have less protection from damaging UV radiation. If you have blond or red hair, light-colored eyes, and freckle or sunburn easily, you’re more likely to develop melanoma than is someone with a darker complexion. But melanoma can develop in people with darker complexions too, including Hispanic people and black people.

- A history of sunburn. One or more severe, blistering sunburns can increase your risk of melanoma.

- Excessive ultraviolet (UV) light exposure. Exposure to UV radiation, which comes from the sun and from tanning lights and beds, can increase the risk of skin cancer, including melanoma. The pattern and timing of the UV exposure may play a role in melanoma development. For example, melanoma on the trunk (chest and back) and legs has been linked to frequent sunburns (especially in childhood). This might also have something to do with the fact that these areas aren’t constantly exposed to UV light. Some evidence suggests that melanomas that start in these areas are different from those that start on the face, neck, and arms, where the sun exposure is more constant. And different from either of these are melanomas on the palms of the hands, soles of the feet, or under the nails (known as acral lentiginous melanomas), or on internal surfaces such as the mouth and vagina (mucosal melanomas), where there has been little or no sun exposure.

- Ultraviolet radiation (UVR):

- Damages skin (sunburn, premature skin aging and cancer)

- Damages eyes (keratitis and cataracts)

- Suppresses immunity in the skin and internally

- Predisposes to bacterial and viral skin infection

- Exacerbates pre-existing actinic keratoses

- Prevents innate immunity from rejecting skin tumors

- Ultraviolet radiation (UVR):

- Living closer to the equator or at a higher elevation. People living closer to the earth’s equator, where the sun’s rays are more direct, experience higher amounts of UV radiation than do those living farther north or south. In addition, if you live at a high elevation, you’re exposed to more UV radiation.

- Having many moles or unusual moles. A mole also known as a nevus, is a benign (non-cancerous) pigmented tumor. Babies are not usually born with moles; they often begin to appear in children and young adults. Most moles will never cause any problems, but having more than 50 ordinary moles on your body indicates an increased risk of melanoma. Also, having an unusual type of mole increases the risk of melanoma. Known medically as dysplastic nevi or atypical moles, these tend to be larger than normal moles and have irregular borders and a mixture of colors. Dysplastic nevi can appear on skin that is exposed to the sun as well as skin that is usually covered, such as on the buttocks or scalp. Dysplastic nevi often run in families. A small percentage of dysplastic nevi may develop into melanomas. But most dysplastic nevi never become cancer, and many melanomas seem to arise without a pre-existing dysplastic nevus.

- Dysplastic nevus syndrome (atypical mole syndrome): People with this inherited condition have many dysplastic nevi. If at least one close relative has had melanoma, this condition is referred to as familial atypical multiple mole and melanoma syndrome (FAMMM). People with familial atypical multiple mole and melanoma syndrome (FAMMM) have a very high lifetime risk of melanoma, so they need to have very thorough, regular skin exams by a dermatologist (a doctor who specializes in skin problems). Sometimes full body photos are taken to help the doctor recognize if moles are changing and growing. Many doctors recommend that these patients be taught to do monthly skin self-exams as well.

- Congenital melanocytic nevi: Moles present at birth are called congenital melanocytic nevi. The lifetime risk of melanoma developing in congenital melanocytic nevi is estimated to be between 0 and 5%, depending on the size of the nevus. People with very large congenital nevi have a higher risk, while the risk is lower for those with small nevi. For example, the risk for melanoma is very low in congenital nevi smaller than the palm of the hand, while those that cover large portions of back and buttocks (“bathing trunk nevi”) have significantly higher risks. Congenital nevi are sometimes removed by surgery so that they don’t have a chance to become cancer. Whether doctors advise removing a congenital nevus depends on several factors including its size, location, and color. Many doctors recommend that congenital nevi that are not removed should be examined regularly by a dermatologist and that the patient should be taught how to do monthly skin self-exams. Again, the chance of any single mole turning into cancer is very low. However, anyone with lots of irregular or large moles has an increased risk for melanoma.

- A family history of melanoma. Your risk of melanoma is higher if one or more of your first-degree relatives (parents, brothers, sisters, or children) has had melanoma. Around 10% of all people with melanoma have a family history of the disease. The increased risk might be because of a shared family lifestyle of frequent sun exposure, a family tendency to have fair skin, certain gene changes (mutations) that run in a family, or a combination of these factors. Most experts don’t recommend that people with a family history of melanoma have genetic testing to look for mutations that might increase risk, as it’s not yet clear how helpful this is. Rather, experts advise that they do the following:

- Have regular skin exams by a dermatologist

- Thoroughly examine their own skin once a month

- Be particularly careful about sun protection and avoiding manmade UV rays (such as those from tanning beds)

- Personal history of melanoma or other skin cancers. A person who has already had melanoma has a higher risk of getting melanoma again. People who have had basal or squamous cell skin cancers are also at increased risk of getting melanoma.

- Weakened immune system. A person’s immune system helps fight cancers of the skin and other organs. People with weakened immune systems (from certain diseases or medical treatments) are more likely to develop many types of skin cancer, including melanoma. Your immune system may be impaired if you take medicine to suppress the immune system, such as after an organ transplant, or if you have a disease that impairs the immune system, such as AIDS.

- Being older. Melanoma is more likely to occur in older people, but it is also found in younger people. In fact, melanoma is one of the most common cancers in people younger than 30 (especially younger women). Melanoma that runs in families may occur at a younger age.

- Being male. In the United States, men have a higher rate of melanoma than women, although this varies by age. Before age 50, the risk is higher for women; after age 50 the risk is higher in men.

- Xeroderma pigmentosum. Xeroderma pigmentosum (XP) is a rare, inherited condition that affects skin cells’ ability to repair damage to their DNA. People with XP have a high risk of developing melanoma and other skin cancers when they are young, especially on sun-exposed areas of their skin.

The main risk factors for developing the most common type of melanoma (superficial spreading melanoma) include:

- Increasing age

- Previous invasive melanoma or melanoma in situ

- Previous basal cell carcinoma (BCC) or squamous cell carcinoma (SCC)

- Many melanocytic nevi (moles)

- Multiple (>5) atypical nevi (large or histologically dysplastic nevi)

- A strong family history of melanoma with 2 or more first-degree relatives affected

- White/fair skin that burns easily

- Parkinson disease also increases the risk of melanoma.

These risk factors are not relevant to rare types of melanoma.

Familial melanoma

Members of certain families are more susceptible to the development of the genetic abnormalities associated with melanoma. As a result, these family members have an exceedingly high risk of developing melanoma. Approximately 8 to 12% of all cases of cutaneous melanoma occur in persons with familial predisposition to the development of melanoma.

Familial human melanoma is characterized by an increased risk of developing primary melanoma, a higher incidence of multiple primary melanomas, and an earlier age at onset 68. These characteristics are common to many other heritable malignant and premalignant conditions such as retinoblastoma, Gardner’s syndrome, xeroderma pigmentosum, and nevoid-basal cell carcinoma 69. In individuals with familial melanoma, the locus for cutaneous malignant melanoma-dysplastic nevus resides on the distal portion of the short arm of chromosome 1. Bale and colleagues 70 suggest that the assignment of the locus for cutaneous melanoma to a region of the human genome frequently involved in karyotypic abnormalities in melanoma cells demonstrates that chromosomal deletion may represent the second event in a recessive model of tumorigenesis. Two genetic lesions relating to p16 and the cell cycle regulating cyclin (CDK4) have been identified in familial melanoma; in these patients, the predisposition to melanoma appears to be associated with an increased risk of developing pancreatic cancer and perhaps other cancers 71. The p53 tumor suppressor gene, although overexpressed in melanoma, may only be a sign of genetic disruption and is not an initiating event 72. All patients and their families should undergo complete skin surveys as part of their routine medical care 73.

Evidence for the genetic cause of melanoma comes from the recognition that chromosomal alterations involving the short arm of chromosome 1 and both arms of chromosomes 6 and 7 have been identified in melanomas and cell lines derived from either primary melanomas or metastases 70. Evidence suggests a 9p21 deletion in familial melanoma 74 and consistent lesions of 9p have become apparent 75. Common losses also occur on chromosomes 10 and 8p, along with gains in copy number for chromosomes 7, 8, 6p, 19, 20, 17, and 2 76.

Melanoma skin cancer prevention

You can reduce your risk of melanoma and other types of skin cancer if you:

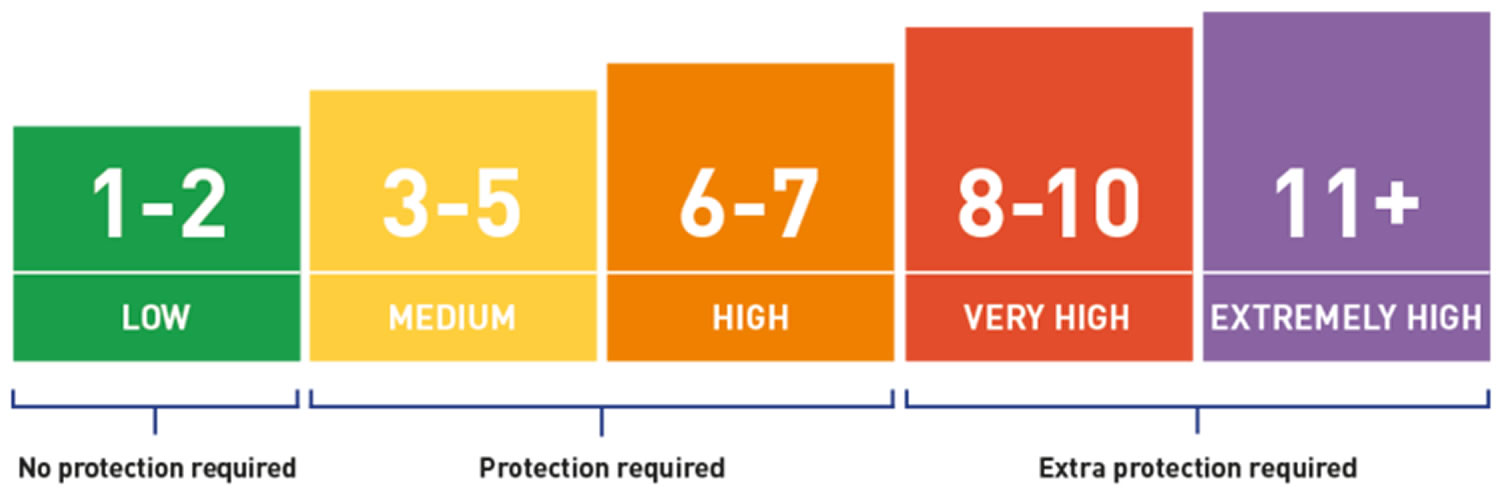

- Avoid the sun during the middle of the day. Ultraviolet radiation (UVR) is the most important preventable risk factor for skin cancer. For many people in North America, the sun’s rays are strongest between about 10 a.m. and 4 p.m. Schedule outdoor activities for other times of the day, even in winter or when the sky is cloudy. You absorb UV radiation year-round, and clouds offer little protection from damaging rays. Avoiding the sun at its strongest helps you avoid the sunburns and suntans that cause skin damage and increase your risk of developing skin cancer. Sun exposure accumulated over time also may cause skin cancer.

- Wear broad spectrum sunscreen year-round. Use a broad-spectrum sunscreen with at least SPF30+, even on cloudy days. Apply sunscreen generously, and reapply every two hours — or more often if you’re swimming or perspiring.

- Wear protective clothing. Cover your skin with dark, tightly woven clothing that covers your arms and legs, and a broad-brimmed hat, which provides more protection than does a baseball cap or visor. Some companies also sell protective clothing. A dermatologist can recommend an appropriate brand. Don’t forget sunglasses. Look for those that block both types of UV radiation — UVA and UVB rays.

- If you are going to be in the sun, “Slip! Slop! Slap! and Wrap” catchphrase can help you remember some of the key steps you can take to protect yourself from UV rays:

- Slip on a shirt.

- Slop on sunscreen.

- Slap on a hat.

- Wrap on sunglasses to protect the eyes and sensitive skin around them.

- If you are going to be in the sun, “Slip! Slop! Slap! and Wrap” catchphrase can help you remember some of the key steps you can take to protect yourself from UV rays:

- Protect children from the sun. Children need special attention, since they tend to spend more time outdoors and can burn more easily. Parents and other caregivers should protect children from excess sun exposure by using the steps above. Children need to be taught about the dangers of too much sun exposure as they become more independent.

- Avoid tanning lamps and beds. Tanning lamps and beds emit UV rays and can increase your risk of skin cancer. Many people believe the UV rays of tanning beds are harmless. This is not true. Tanning lamps give off UV rays, which can cause long-term skin damage and can contribute to skin cancer. Tanning bed use has been linked with an increased risk of melanoma, especially if it is started before a person is 30. Most dermatologists (skin doctors) and health organizations recommend not using tanning beds and sun lamps.

- Become familiar with your skin so that you’ll notice changes. Examine your skin often for new skin growths or changes in existing moles, freckles, bumps and birthmarks. With the help of mirrors, check your face, neck, ears and scalp. Examine your chest and trunk and the tops and undersides of your arms and hands. Examine both the front and back of your legs and your feet, including the soles and the spaces between your toes. Also check your genital area and between your buttocks.

What is ultraviolet radiation?

Ultraviolet radiation (UVR) forms part of the electromagnetic spectrum — the energy emitted from the sun. Ultraviolet radiation (UVR) is categorized according to wavelength, which ranges from 100–400 nm 77.

- Ultraviolet radiation (UVR) is involved in tanning, accelerated skin ageing, ocular damage, and the development of skin cancer.