Mycosis fungoides

Mycosis fungoides is the most common form of cutaneous T cell lymphoma or non-Hodgkin lymphoma that first appears on the skin and can spread to the lymph nodes or other organs such as the spleen, liver, or lungs 1. Although the terms mycosis fungoides and cutaneous T cell lymphoma are often used interchangeably, this can be a source of confusion. All cases of mycosis fungoides are cutaneous T cell lymphoma, but not all cutaneous T cell lymphoma cases are mycosis fungoides. Mycosis fungoides is a disease in which lymphocytes (a type of white blood cell) become malignant (cancerous) and affect the skin. Mycosis fungoides is considered a low-grade skin malignancy which cannot be cured but is usually treatable. Mycosis fungoides follows a slow, chronic (indolent) course and very often does not spread beyond the skin. Prognosis depends on the stage of the condition. For people with early stage mycosis fungoides, the impact of disease on overall survival is minimal. As the disease advances the impact on survival becomes of greater concern.

Mycosis fungoides predominantly affects elderly adults (median age 55-60), but can be seen in any age group, including children 2. The male-to-female ratio is about 2:1 2.

Mycosis fungoides is not an infection and cannot be passed from person to person.

In about 10% of cases, mycosis fungoides can progress to lymph nodes and internal organs. Symptoms of mycosis fungoides can include flat, red, scaly patches, thicker raised lesions calls plaques, and sometimes large nodules called tumors on the skin. Mycosis fungoides typically presents as red, scaly patches on the skin around the abdomen and buttocks in a so-called “bathing suit” distribution (see Figure 2 below). These areas are often itchy but not usually painful. More advanced lesions can be thick or raised and can be accompanied by the development of lumps or widespread redness. Mycosis fungoides can look like other common skin conditions like eczema or psoriasis, and might be present for years or even decades before it’s diagnosed as cutaneous T cell lymphoma. Mycosis fungoides can progress over many years, often decades.

Obtaining a skin biopsy is usually necessary to reach a diagnosis of mycosis fungoides. Because the changes in early mycosis fungoides can be subtle, several biopsies over time may be needed to establish a diagnosis. Sometimes other tests such as blood tests, X-rays, CT scans or PET (positron emission tomography) scans can also be helpful.

There is continuing research into possible environmental or infectious agents that might contribute to mycosis fungoides, but at this time no single factor has been proven to cause this disease. One theory about how mycosis fungoides might occur is because of chronic low-level stimulation of T-cells in the skin. There is no supportive research indicating that mycosis fungoides is hereditary. Exposure to Agent Orange may be a risk factor for developing mycosis fungoides for veterans of the Vietnam War, but no direct cause-effect relationship has been established.

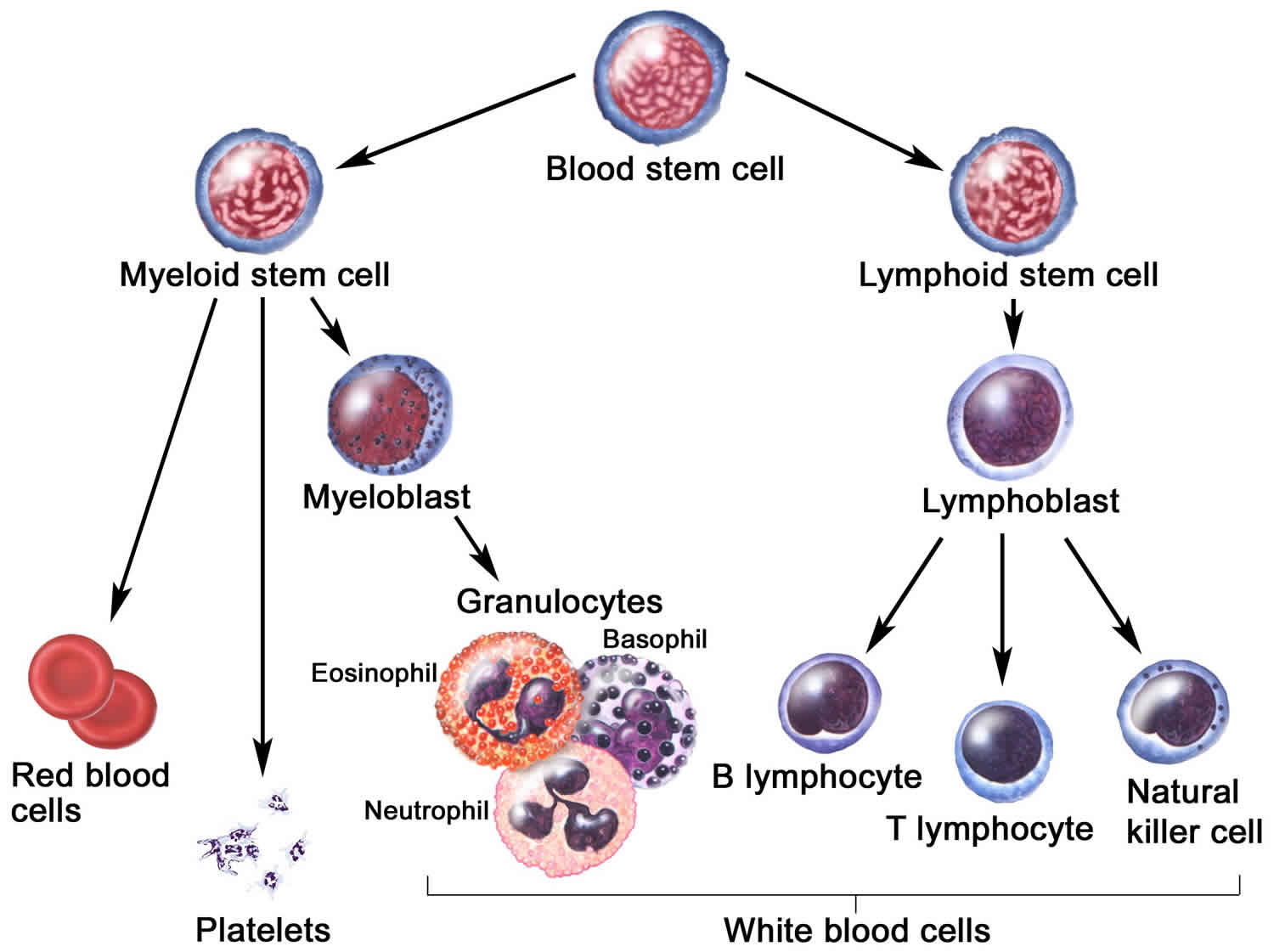

Normally, the bone marrow makes blood stem cells (immature cells) that become mature blood stem cells over time. A blood stem cell may become a myeloid stem cell or a lymphoid stem cell. A myeloid stem cell becomes a red blood cell, white blood cell, or platelet. A lymphoid stem cell becomes a lymphoblast and then one of three types of lymphocytes (white blood cells):

- B-cell lymphocytes that make antibodies to help fight infection.

- T-cell lymphocytes that help B-lymphocytes make the antibodies that help fight infection.

- Natural killer cells that attack cancer cells and viruses.

In mycosis fungoides, T-cell lymphocytes become cancerous and affect the skin. Malignant T cells are small, medium in size, and characteristically have irregular cerebriform nuclei. When these lymphocytes occur in the blood, they are called Sézary cells. In Sézary syndrome, cancerous T-cell lymphocytes affect the skin and large numbers of Sézary cells (cancerous T-cells) are found in the blood. Also, skin all over the body is reddened, itchy, peeling, and painful. There may also be patches, plaques, or tumors on the skin. It is not known if Sézary syndrome is an advanced form of mycosis fungoides or a separate disease.

There are numerous clinical and histopathological variants of mycosis fungoides including a folliculotropic variant, a granulomatous variant (granulomatous slack skin syndrome), and variants that mimic common dermatoses such as pigmented purpuric dermatitis and vitiligo.

Mycosis fungoides may go through the following phases:

- Premycotic phase: A scaly, red rash in areas of the body that usually are not exposed to the sun. This rash does not cause symptoms and may last for months or years. It is hard to diagnose the rash as mycosis fungoides during this phase.

- Mycosis fungoides patch phase: Thin, reddened, eczema-like rash. Patch phase mycosis fungoides there is a superficial lichenoid infiltrate, mainly lymphocytes and histiocytes and a few atypical cells infiltrating the epidermis without significant spongiosis (a phenomenon which is known as ‘exocytosis’). This stage may be very subtle histopathologically and mimic other dermatoses such as eczema or lichenoid dermatoses, as the atypia may be difficult to appreciate. Often multiple biopsies are required to make the diagnosis and numerous studies may be needed to isolate or prove a clonal proliferation of T cells.

- Mycosis fungoides plaque phase: Small raised bumps (papules) or hardened lesions on the skin, which may be reddened. As mycosis fungoides progresses, there is more obvious epidermotropism and a denser dermal infiltrate. There may be intraepidermal collections of atypical cells (Pautrier microabscesses).

- Mycosis fungoides tumor phase: Tumors form on the skin. These tumors may develop ulcers and the skin may get infected. There may be no exocytosis of lymphocytes in this stage. Transformation to large cells may occur.

Check with your doctor if you have any of these signs.

The treatment of mycosis fungoides depends on the area of skin affected and the stage of disease.

Treatment options include:

- Corticosteroid creams and ointments

- Topic nitrogen mustard

- Narrow-band UVB phototherapy

- PUVA phototherapy

- Radiotherapy

- Methotrexate

- Acitretin

- Interferon

- Extracorporeal photophoresis

- Chemotherapy

- Allogeneic stem cell transplantation.

Figure 1. Blood cell development

Figure 2. Mycosis fungoides rash

How common is mycosis fungoides?

As a group, cutaneous T cell lymphoma is a rare family of diseases. While the number of new cases diagnosed each year is relatively low (about 3,000), it is estimated that, since patients have a very long survival, there may be as many as 30,000 patients living with cutaneous lymphoma in the United States and Canada. Mycosis fungoides is more common in men compared to women, in blacks compared to whites, and in patients older than 50 years of age compared to younger people. Due to the difficulty of diagnosing the disease in its early stages, the slow course of mycosis fungoides, and the lack of an accurate reporting system, these numbers are probably low estimates.

Folliculotropic mycosis fungoides

Folliculotropic mycosis fungoides is a subtype of mycosis fungoides that involves hair follicles. About 10% of mycosis fungoides patients have folliculotropic mycocis fungoides. Mycosis fungoides lesions include flat, red, scaly patches, thicker raised lesions (plaques), and sometimes larger nodules or tumors. Patients with folliculotropic mycosis fungoides might also notice areas of hair loss, especially around the face or scalp, pimples or blackheads, or increased infections within their plaques because of involvement of the hair follicles. Patients with folliculotropic mycosis fungoides might experience itching. Patients may also experience no specific symptoms related to their skin rash.

It is difficult to diagnose folliculotropic mycosis fungoides in its early stages, and there is not an accurate reporting system.

There is no clear known cause for mycosis fungoides or folliculotropic mycocis fungoides. Cutaneous lymphomas are not contagious and cannot be passed from one person to another, and they generally are not inherited.

Many of the same procedures used to diagnose and stage other types of cutaneous T cell lymphomas are used in folliculotropic mycosis fungoides, including:

- A physical exam and history;

- A skin and/or lymph node biopsy (removal of a small piece of tissue) for examination under the microscope by a pathologist (a doctor who studies tissues and cells to identify diseases);

- A series of imaging tests such as CT (computerized axial tomography and/or PET (positron emission tomography) scans to determine if the cancer has spread to lymph nodes or other organs.

- When examined under the microscope, skin biopsies from folliculotropic mycosis fungoides patients show involvement around hair follicles (“folliculotropism”).

Is important to confirm the diagnosis of folliculotropic mycosis fungoides by a dermatopathologist or a hematopathologist who has expertise in diagnosing lymphomas.

Folliculotopic mycosis fungoides causes

Although there is continuing research, currently no single factor is known to cause cutaneous lymphomas. Cutaneous lymphomas are acquired diseases with no clear genetic or hereditary link, and they are not contagious.

Despite a number of anecdotal reports, there does not seem to be a clear or defined link between cutaneous lymphoma and chemical exposure, pesticides, radiation, allergies, the environment, or occupations. Exposure to Agent Orange may be a risk factor for developing mycosis fungoides, but no direct causal relationship has been shown.

Folliculotropic mycosis fungoides staging

The following staging system is used to determine the extent of folliculotropic mycosis fungoides:

- Stage 1A: Less than 10 percent of the skin is covered in red patches and/or plaques.

- Stage 1B: Ten percent or more of the skin surface is covered in patches and/or plaques.

- Stage 2A: Any amount of the skin surface is covered with patches and/or plaques; lymph nodes are enlarged, but the cancer has not spread to them.

- Stage 2B: One or more tumors are found on the skin; lymph nodes may be enlarged, but the cancer has not spread to them.

- Stage 3: Nearly all of the skin is reddened and may have patches, plaques or tumors; lymph nodes may be enlarged, but the cancer has not spread to them.

- Stage 4A: Most of the skin area is reddened and there is involvement of the blood with malignant cells or any amount of the skin surface is covered with patches, plagues or tumors; cancer has spread to the lymph nodes and the lymph nodes may be enlarged.

- Stage 4B: Most of the skin is reddened or any amount of the skin surface is covered with patches, plaques or tumors; cancer has spread to other organs; and lymph nodes may be enlarged whether cancer has spread to them or not.

Folliculotropic mycosis fungoides treatment

Folliculotropic mycosis fungoides is generally treated similar to other forms of mycosis fungoides, but need to be monitored more closely because of involvement of hair follicles. Most patients should first be treated with skin directed treatments like light (photo)therapy and topical agents. If skin directed treatments don’t work, then systemic agents (pills, injections, or intravenous treatments) are added. The list of systemic agents for cutaneous T cell lymphomas is growing, and includes retinoids, interferon injections, histone deacetylase inhibitors (vorinostat and romidepsin), and antibody-based therapies, among others.

Skin radiation is also commonly used to treat folliculotropic mycosis fungoides. Skin radiation for folliculotropic mycosis fungoides is usually a low dose method (electron beam) that spares the internal organs.

A very small number of patients with folliculotropic mycosis fungoides need more aggressive therapy with chemotherapy or a stem cell transplant to control their disease.

Folliculotropic mycosis fungoides prognosis

The prognosis of folliculotropic mycosis fungoides is determined by the type and the extent of skin involvement and overall stage.

Early stage folliculotropic mycosis fungoides has a prognosis very similar to classic mycoses fungoides, with excellent survival. People with more advanced folliculotropic mycosis fungoides (thicker lesions or tumors or involvement deeper in the skin) are more likely to progress to more advanced stages. Large cell transformation is a sign of progression, and may indicate more serious disease. Involvement of organs other than the skin (such as the lungs or liver), lymph nodes, or blood also indicate more serious disease.

Mycosis fungoides patch stage

Staging for mycosis fungoides correlate with the progressive density of malignant T cells.

Mycosis fungoides stage is based on 4 factors:

- T describes how much of the skin is affected by the lymphoma (tumor).

- N describes the extent of the lymphoma in the lymph nodes (bean-sized collections of immune cells).

- M is for the spread (metastasis) of the lymphoma to other organs.

- B is for lymphoma cells in the blood.

T categories

- T1: Skin lesions can be small patches (flat lesions), papules (small bumps), and/or plaques (raised or lowered, flat lesions), but the lesions cover less than 10% of the skin surface.

- T2: The patches, papules, and/or plaques cover 10% or more of the skin surface.

- T3: At least one of the skin lesions is a tumor (a lesion growing deeper into the skin) that is at least 1 centimeter (cm) (a little less than 1/2 inch) across.

- T4: The skin lesions have grown together to cover at least 80% of the skin surface.

N categories

- N0: Lymph nodes are not enlarged and a lymph node biopsy is not needed.

- N1: Lymph nodes are enlarged, but the patterns of cells look normal or close to normal under the microscope.

- N2: Lymph nodes are enlarged, and the patterns of cells look more abnormal under the microscope.

- N3: Lymph nodes are enlarged, and the patterns of cells look very abnormal under the microscope.

- NX: Lymph nodes are enlarged but haven’t been removed (biopsied) to be looked at under the microscope.

M categories

- M0: The lymphoma cells have not spread to other organs.

- M1: Lymphoma cells have spread to other organs, such as the liver or spleen.

B categories

- B0: No more than 5% of lymphocytes in the blood are Sezary (lymphoma) cells.

- B1: Low numbers of Sezary cells in the blood (more than in B0 but less than in B2).

- B2: High number of Sezary cells in the blood.

Stage grouping

Once the values for T, N, M, and B are known, they are combined to determine the overall stage of the lymphoma. This process is called stage grouping.

Mycosis fungoides stages range from I (1) through IV (4). As a rule, the lower the number, the less the cancer has spread. A higher number, such as stage 4, means cancer has spread more. And within a stage, an earlier letter means a lower stage. Although each person’s cancer experience is unique, cancers with similar stages tend to have a similar outlook and are often treated in much the same way.

The following stages are used for mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome:

Stage 1 Mycosis Fungoides

Stage 1 is divided into stages IA and IB as follows:

- Stage 1A (T1, N0, M0, B0 or B1): There are skin lesions but no tumors. Patches, papules, and/or plaques cover less than 10% of the skin surface (T1), the lymph nodes are not enlarged (N0), lymphoma cells have not spread to other organs (M0), and the number of Sezary cells in the blood is not high (B0 or B1).

- Stage 1B (T2, N0, M0, B0 or B1): There are skin lesions but no tumors. Patches, papules, and/or plaques cover 10% or more of the skin surface (T2), the lymph nodes are not enlarged (N0), lymphoma cells have not spread to other organs (M0), and the number of Sezary cells in the blood is not high (B0 or B1).

There may be a low number of Sézary cells in the blood.

Stage 2 Mycosis Fungoides

Stage 2 is divided into stages 2A and 2B as follows:

- Stage 2A (T1 or T2, N1 or N2, M0, B0 or B1): There are skin lesions but no tumors. Patches, papules, and/or plaques can cover up to 80% of the skin surface (T1 or T2). Lymph nodes are enlarged but the patterns of cells do not look very abnormal under the microscope (N1 or N2). Lymphoma cells have not spread to other organs (M0), and the number of Sezary cells in the blood is not high (B0 or B1).

- Stage 2B (T3, N0 to N2, M0, B0 or B1): At least one of the skin lesions is a tumor that is 1 cm across or larger (T3). Lymph nodes may be abnormal, but they are not cancerous (N1 or N2). Lymphoma cells have not spread to other organs (M0), and the number of Sezary cells in the blood is not high (B0 or B1).

There may be a low number of Sézary cells in the blood.

Stage 3 Mycosis Fungoides

In stage 3, 80% or more of the skin surface is reddened and may have patches, papules, plaques, or tumors. Lymph nodes may be abnormal, but they are not cancerous.

- Stage 3A (T4, N0 to N2, M0, B0): Skin lesions cover at least 80% of the skin surface (T4). The lymph nodes are either normal (N0) or are enlarged but the patterns of cells do not look very abnormal under the microscope (N1 or N2). Lymphoma cells have not spread to other organs or tissues (M0), and no more than 5% of the lymphocytes in the blood are Sezary cells (B0).

- Stage 3B (T4, N0 to N2, M0, B1): Skin lesions cover at least 80% of the skin surface (T4). The lymph nodes are either normal (N0) or are enlarged but the patterns of cells do not look very abnormal under the microscope (N1 or N2). Lymphoma cells have not spread to other organs (M0), and the number of Sezary cells in the blood is low (B1).

There may be a low number of Sézary cells in the blood.

Stage 4 Mycosis Fungoides/Sézary Syndrome

When there is a high number of Sézary cells in the blood, the disease is called Sézary syndrome.

Stage 4 is divided into stages IVA1, IVA2, and IVB as follows:

- Stage 4A1 (Any T, N0 to N2, M0, B2): Patches, papules, plaques, or tumors may cover any amount of the skin surface (any T) and 80% or more of the skin surface may be reddened. The lymph nodes may be abnormal, but they are not cancerous (N1 or N2). Lymphoma cells have not spread to other organs (M0), and the number of Sezary cells in the blood is high (B2).

- Stage 4A2 (Any T, N3, M0, any B): Patches, papules, plaques, or tumors may cover any amount of the skin surface (any T), and 80% or more of the skin surface may be reddened. The lymph nodes are very abnormal, or cancer has formed in the lymph nodes (N3). Lymphoma cells have not spread to other organs (M0). Sezary cells may or may not be in the blood (any B).

- Stage 4B (Any T, any N, M1, any B): Lymphoma cells have spread to other organs in the body, such as the spleen or liver (M1). Patches, papules, plaques, or tumors may cover any amount of the skin surface (any T) and 80% or more of the skin surface may be reddened. The lymph nodes may be abnormal or cancerous (any N). There may be a high number of Sézary cells in the blood.

Mycosis fungoides causes

The cause of mycosis fungoides is still unclear, but genetic mutations and occupational exposure have been implied 3. In its classic form, mycosis fungoides is an indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma with prolonged clinical course, presenting as erythematous scaly patches that evolve slowly into plaques and tumors in some patients. Less than one-third of patients show an advanced clinical course with involvement of lymph nodes and/or visceral organs, usually involving large cell transformation 4. Over the past decades, a variety of clinical, histological and immunohistochemical subtypes of mycosis fungoides have been described. Although most of these are considered to be minor variants of classic mycosis fungoides, few are recognized as separate subtypes according to the World Health Organization (WHO) classification system of tumors of hematopoietic and lymphoid tissues 5.

Mycosis fungoides symptoms

A common symptom of mycosis fungoides is itching, with 80 percent or more of people with mycosis fungoides suffering from itching. One of the challenging things about mycosis fungoides is that it doesn’t look the same for all patients.

Mycosis fungoides can appear anywhere on the body, but tends to affect areas of the skin protected from sun by clothing. Patches, plaques and tumors are the clinical names for different skin manifestations and are generally defined as “lesions.”

- Patches are usually flat, can be smooth or scaly, and look like a “rash.” In patch stage mycosis fungoides, the skin lesions are flat. Most often there are oval or ring-shaped (annular) pink dry patches on covered skin. They may spontaneously disappear, remain the same size, or slowly enlarge. The skin may be atrophic (thinned), and may or may not itch. The patch stage of mycosis fungoides can be difficult to distinguish from psoriasis, discoid eczema or parapsoriasis.

- Plaques are thicker, raised, usually scaly lesions. In plaque stage mycosis fungoides, the patches become thickened and may resemble psoriasis. They are usually itchy. Mycosis fungoides patches and plaques are often mistaken for eczema, psoriasis or “non-specific” dermatitis until an exact diagnosis is made.

- Tumors are raised “bumps” or “nodules” which may or may not ulcerate (form sores). In tumor stage mycosis fungoides, large irregular lumps develop from plaques, or de novo. They may ulcerate. At this stage, spread to other organs is more likely than in earlier stages. The tumour type may transform into a large cell lymphoma.

While it is possible to have all three types of lesions at the same time, most people who have had mycosis fungoides for many years experience only one or two types of lesions, generally patches and plaques. Only rarely are the tumors the first lesion.

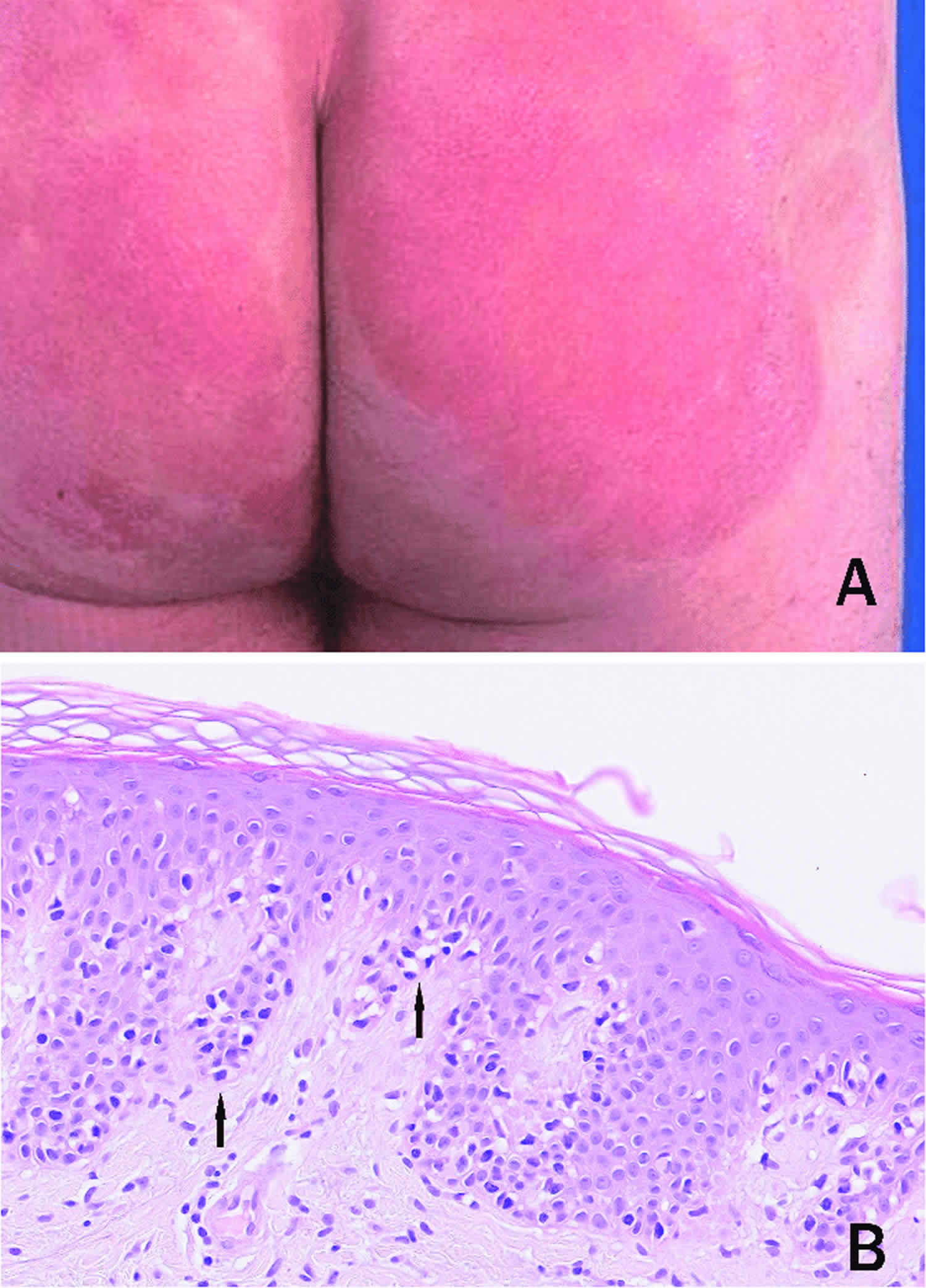

Figure 3. Mycosis fungoides patches

Footnote:Patch stage mycosis fungoides. (A) Erythematous, sharply demarcated patches on the buttocks of a patient. (B) Infiltration of hyperchromatic and enlarged haloed lymphocytes along the dermoepidermal junction (indicated by arrows) and a sparse infiltrate in the superficial dermis. Hematoxylin & eosin staining, X20.

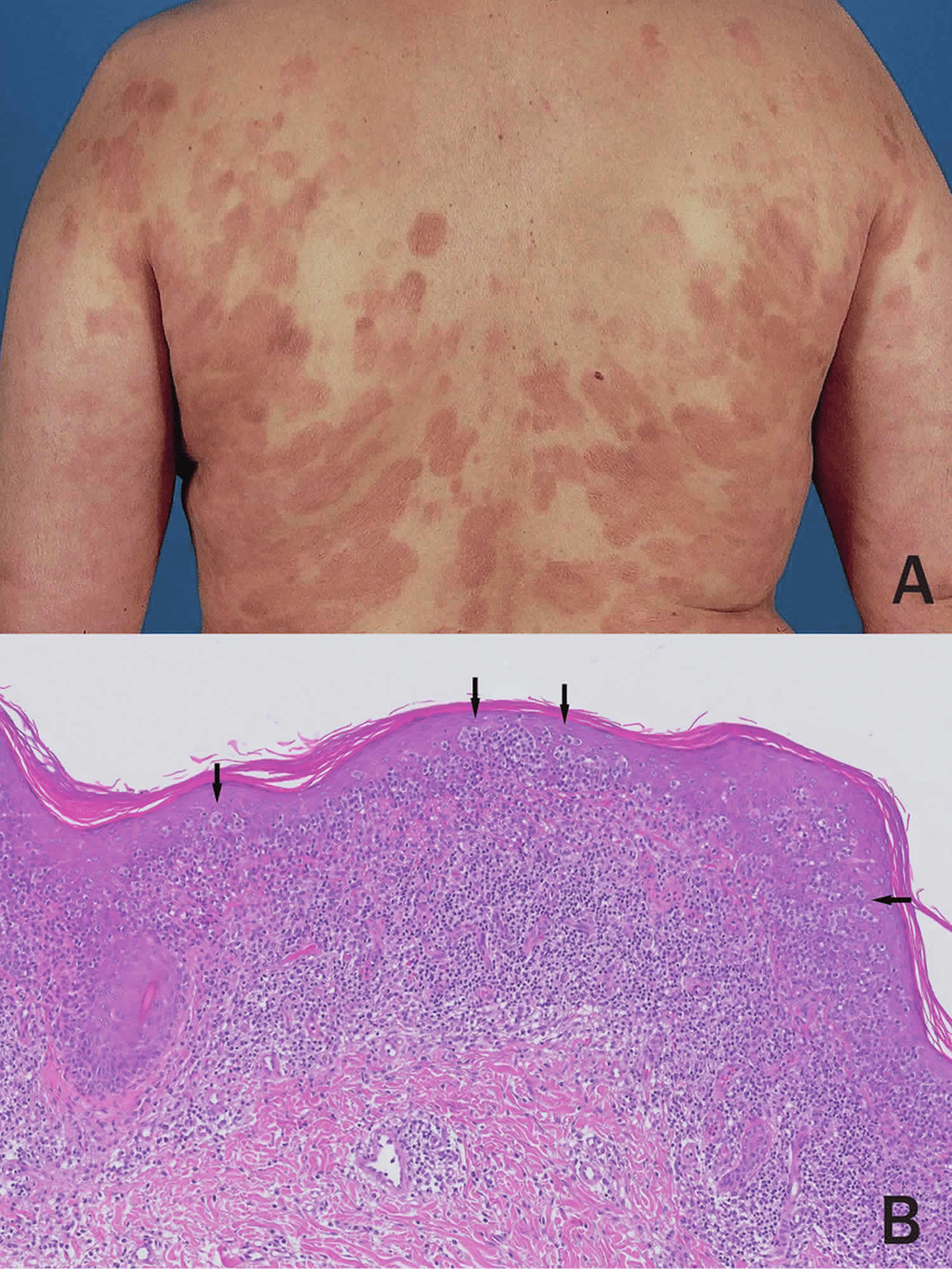

[Source 2 ]Figure 4. Mycosis fungoides plaques

Footnote: Plaque stage mycosis fungoides. (A) Infiltrative and coalescing lesions on the trunk of a patient. (B) Dense, band-like infiltrate in the superficial dermis and considerable epidermotropism by atypical lymphocytes with formation of intraepidermal clusters (arrows). Hematoxylin & eosin staining, X10.

[Source 2 ]Figure 5. Mycosis fungoides tumor

Footnote: Tumor stage mycosis fungoides.

Mycosis fungoides diagnosis

Mycosis fungoides is very difficult to diagnose, especially in early stages. The symptoms and skin biopsy findings of mycosis fungoides are similar to other benign skin conditions like eczema, psoriasis, parapsoriasis, or pityriasis lichenoides. Patients may go for years or even decades before a definitive diagnosis of mycosis fungoides is established. Mycosis fungoides is sometimes diagnosed initially only by dermatologists or oncologists who specialize in cutaneous lymphomas.

Tests that examine the skin and blood are used to diagnose mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome.

Typical procedures done to diagnose mycosis fungoides include:

- A complete physical exam and health history: An exam of the body to check general signs of health, including checking for signs of disease, such as lumps, the number and type of skin lesions, or anything else that seems unusual. Pictures of the skin and a history of the patient’s health habits and past illnesses and treatments will also be taken.

- A skin and/or lymph node biopsy (removal of a small piece of tissue) for examination under the microscope by a pathologist (a doctor who studies tissues and cells to identify diseases):

- Skin biopsy: The removal of cells or tissues so they can be viewed under a microscope to check for signs of cancer. The doctor may remove a growth from the skin, which will be examined by a pathologist. More than one skin biopsy may be needed to diagnose mycosis fungoides. Other tests that may be done on the cells or tissue sample include the following:

- Immunophenotyping: A laboratory test that uses antibodies to identify cancer cells based on the types of antigens or markers on the surface of the cells. This test is used to help diagnose specific types of lymphoma.

- Flow cytometry: A laboratory test that measures the number of cells in a sample, the percentage of live cells in a sample, and certain characteristics of the cells, such as size, shape, and the presence of tumor (or other) markers on the cell surface. The cells from a sample of a patient’s blood, bone marrow, or other tissue are stained with a fluorescent dye, placed in a fluid, and then passed one at a time through a beam of light. The test results are based on how the cells that were stained with the fluorescent dye react to the beam of light. This test is used to help diagnose and manage certain types of cancers, such as leukemia and lymphoma.

- T-cell receptor (TCR) gene rearrangement test: A laboratory test in which cells in a sample of blood or bone marrow are checked to see if there are certain changes in the genes that make receptors on T cells (white blood cells). Testing for these gene changes can tell whether large numbers of T cells with a certain T-cell receptor are being made.

- Skin biopsy: The removal of cells or tissues so they can be viewed under a microscope to check for signs of cancer. The doctor may remove a growth from the skin, which will be examined by a pathologist. More than one skin biopsy may be needed to diagnose mycosis fungoides. Other tests that may be done on the cells or tissue sample include the following:

- Complete blood count with differential: A procedure in which a sample of blood is drawn and checked for the following:

- The number of red blood cells and platelets.

- The number and type of white blood cells.

- The amount of hemoglobin (the protein that carries oxygen) in the red blood cells.

- The portion of the blood sample made up of red blood cells.

- Sézary blood cell count: A procedure in which a sample of blood is viewed under a microscope to count the number of Sézary cells.

- HIV test: A test to measure the level of HIV antibodies in a sample of blood. Antibodies are made by the body when it is invaded by a foreign substance. A high level of HIV antibodies may mean the body has been infected with HIV.

- And possibly imaging tests such as CT (computerized axial tomography and/or PET (positron emission tomography) scans.

Is very important that any diagnosis of mycosis fungoides is confirmed by a pathologist who has expertise in diagnosing cutaneous lymphomas.

After mycosis fungoides (and Sézary syndrome) have been diagnosed, tests are done to find out if cancer cells have spread from the skin to other parts of the body.

The process used to find out if cancer has spread from the skin to other parts of the body is called staging. The information gathered from the staging process determines the stage of the disease. It is important to know the stage in order to plan treatment.

The following procedures may be used in the staging process:

- Chest x-ray: An x-ray of the organs and bones inside the chest. An x-ray is a type of energy beam that can go through the body and onto film, making a picture of areas inside the body.

- CT scan (CAT scan): A procedure that makes a series of detailed pictures of areas inside the body, such as the lymph nodes, chest, abdomen, and pelvis, taken from different angles. The pictures are made by a computer linked to an x-ray machine. A dye may be injected into a vein or swallowed to help the organs or tissues show up more clearly. This procedure is also called computed tomography, computerized tomography, or computerized axial tomography.

- PET scan (positron emission tomography scan): A procedure to find malignant tumor cells in the body. A small amount of radioactive glucose (sugar) is injected into a vein. The PET scanner rotates around the body and makes a picture of where glucose is being used in the body. Malignant tumor cells show up brighter in the picture because they are more active and take up more glucose than normal cells do.

- Lymph node biopsy: The removal of all or part of a lymph node. A pathologist views the lymph node tissue under a microscope to check for cancer cells.

- Bone marrow aspiration and biopsy: The removal of bone marrow and a small piece of bone by inserting a hollow needle into the hipbone or breastbone. A pathologist views the bone marrow and bone under a microscope to look for signs of cancer.

There are three ways that cancer spreads in the body.

Cancer can spread through tissue, the lymph system, and the blood:

- Tissue. The cancer spreads from where it began by growing into nearby areas.

- Lymph system. The cancer spreads from where it began by getting into the lymph system. The cancer travels through the lymph vessels to other parts of the body.

- Blood. The cancer spreads from where it began by getting into the blood. The cancer travels through the blood vessels to other parts of the body.

Cancer may spread from where it began to other parts of the body.

When cancer spreads to another part of the body, it is called metastasis. Cancer cells break away from where they began (the primary tumor) and travel through the lymph system or blood.

- Lymph system. The cancer gets into the lymph system, travels through the lymph vessels, and forms a tumor (metastatic tumor) in another part of the body.

- Blood. The cancer gets into the blood, travels through the blood vessels, and forms a tumor (metastatic tumor) in another part of the body.

The metastatic tumor is the same type of cancer as the primary tumor. For example, if mycosis fungoides spreads to the liver, the cancer cells in the liver are actually mycosis fungoides cells. The disease is metastatic mycosis fungoides, not liver cancer.

Mycosis fungoides treatment

The treatment of mycosis fungoides is continuously evolving and improving. Different types of treatment are available for patients with mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome. Some treatments are standard (the currently used treatment), and some are being tested in clinical trials. A treatment clinical trial is a research study meant to help improve current treatments or obtain information on new treatments for patients with cancer. When clinical trials show that a new treatment is better than the standard treatment, the new treatment may become the standard treatment. Patients may want to think about taking part in a clinical trial. Some clinical trials are open only to patients who have not started treatment. It’s important to discuss clinical trials with your care provider.

Selecting the right treatment or combination of treatments for you can be daunting, and it’s important to work with a specialist who has experience treating patients with mycosis fungoides.

You may be prescribed a single treatment or a combination of treatments.

Seven types of standard treatment are used:

Photodynamic therapy

Photodynamic therapy is a cancer treatment that uses a drug and a certain type of laser light to kill cancer cells. A drug that is not active until it is exposed to light is injected into a vein. The drug collects more in cancer cells than in normal cells. For skin cancer, laser light is shined onto the skin and the drug becomes active and kills the cancer cells. Photodynamic therapy causes little damage to healthy tissue. Patients undergoing photodynamic therapy will need to limit the amount of time spent in sunlight. There are different types of photodynamic therapy:

- In psoralen and ultraviolet A (PUVA) therapy, the patient receives a drug called psoralen and then ultraviolet A radiation is directed to the skin.

- In extracorporeal photochemotherapy, the patient is given drugs and then some blood cells are taken from the body, put under a special ultraviolet A light, and put back into the body. Extracorporeal photochemotherapy may be used alone or combined with total skin electron beam radiation therapy.

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy is a cancer treatment that uses high-energy x-rays or other types of radiation to kill cancer cells or keep them from growing. External radiation therapy uses a machine outside the body to send radiation toward the area of the body with cancer. Sometimes, total skin electron beam (TSEB) radiation therapy is used to treat mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome. This is a type of external radiation treatment in which a radiation therapy machine aims electrons (tiny, invisible particles) at the skin covering the whole body. External radiation therapy may also be used as palliative therapy to relieve symptoms and improve quality of life.

Ultraviolet A (UVA) radiation therapy or ultraviolet B (UVB) radiation therapy may be given using a special lamp or laser that directs radiation at the skin.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is a cancer treatment that uses drugs to stop the growth of cancer cells, either by killing the cells or by stopping them from dividing. When chemotherapy is taken by mouth or injected into a vein or muscle, the drugs enter the bloodstream and can reach cancer cells throughout the body (systemic chemotherapy). Sometimes the chemotherapy is topical (put on the skin in a cream, lotion, or ointment).

Other drug therapy

Topical corticosteroids are used to relieve red, swollen, and inflamed skin. They are a type of steroid. Topical corticosteroids may be in a cream, lotion, or ointment.

Retinoids, such as bexarotene, are drugs related to vitamin A that can slow the growth of certain types of cancer cells. The retinoids may be taken by mouth or put on the skin.

Lenalidomide is a drug that helps the immune system kill abnormal blood cells or cancer cells and may prevent the growth of new blood vessels that tumors need to grow.

Vorinostat and romidepsin are two of the histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors used to treat mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome. HDAC inhibitors cause a chemical change that stops tumor cells from dividing.

Immunotherapy

Immunotherapy is a treatment that uses the patient’s immune system to fight cancer. Substances made by the body or made in a laboratory are used to boost, direct, or restore the body’s natural defenses against cancer. This type of cancer treatment is also called biotherapy or biologic therapy.

- Interferon: This treatment interferes with the division of mycosis fungoides and Sézary cells and can slow tumor growth.

Targeted therapy

Targeted therapy is a type of treatment that uses drugs or other substances to attack cancer cells. Targeted therapies usually cause less harm to normal cells than chemotherapy or radiation therapy do.

Monoclonal antibody therapy: This treatment uses antibodies made in the laboratory from a single type of immune system cell. These antibodies can identify substances on cancer cells or normal substances that may help cancer cells grow. The antibodies attach to the substances and kill the cancer cells, block their growth, or keep them from spreading. They may be used alone or to carry drugs, toxins, or radioactive material directly to cancer cells. Monoclonal antibodies are given by infusion.

Types of monoclonal antibodies include:

- Brentuximab vedotin, which contains a monoclonal antibody that binds to a protein, called CD30, found on some types of lymphoma cells. It also contains an anticancer drug that may help kill cancer cells.

- Mogamulizumab, which contains a monoclonal antibody that binds to a protein, called CCR4, found on some types of lymphoma cells. It may block this protein and help the immune system kill cancer cells. It is used to treat mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome that came back or did not get better after treatment with at least one systemic therapy.

High-dose chemotherapy and radiation therapy with stem cell transplant

High doses of chemotherapy and sometimes radiation therapy are given to kill cancer cells. Healthy cells, including blood-forming cells, are also destroyed by the cancer treatment. Stem cell transplant is a treatment to replace the blood-forming cells. Stem cells (immature blood cells) are removed from the blood or bone marrow of the patient or a donor and are frozen and stored. After the patient completes chemotherapy and radiation therapy, the stored stem cells are thawed and given back to the patient through an infusion. These reinfused stem cells grow into (and restore) the body’s blood cells.

Skin-directed therapies

In most patients with mycosis fungoides, the lymphoma cells are primarily limited to the skin, and one can have excellent and long-lasting responses with treatments directed at the skin, or “skin directed therapy”. Because treatment is directed just at the skin, the toxicity of these treatments is low. Examples of skin directed therapies are creams, ointments, or gels that are applied to the skin, such as topical steroids, topical nitrogen mustard, retinoids, and immune stimulating creams (imiquimod). Ultraviolet light (“medical tanning”) and radiation therapy are also types of skin directed therapy.

Systemic therapies

“Systemic therapy” refers any treatment that, after absorption, reaches the bloodstream and is therefore distributed across the body “system.” Any drug that is taken by mouth, given as a suppository, injected under the skin, taken under the tongue, or directly infused through a blood vessel will eventually reach all body organs and tissues (including the skin), with the exception of the brain, which by design is protected by a specific “barrier.” Systemic therapies are used in mycosis fungoides when skin directed therapies aren’t working well enough, or are to difficult to apply, or the disease is advanced. Systemic therapies may be used alone or in combination, and are often used together with skin directed therapies (for example using a pill to make you more sensitive to ultraviolet light therapy). Nearly all of the systemic therapies used in mycosis fungoides are considered “targeted” drugs, which means that they work in different ways than “traditional” or “standard” chemotherapy.

There are many examples of systemic therapies that are used in mycosis fungoides, including pills such as bexarotene, methotrexate and vorinostat; infusional therapies like pralatrextate and romidepsin, and immunotherapies like pembroluzimab. Traditional or standard chemotherapy, which would be used for other blood cancers, is only rarely used in mycosis fungoides because of severe side effects and a high rate of mycosis fungoides returning after treatment.

Mycosis fungoides prognosis

Certain factors affect prognosis (chance of recovery) and treatment options.

The prognosis and treatment options depend on the following:

- The stage of the cancer.

- The type of lesion (patches, plaques, or tumors).

- The patient’s age and gender.

Mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome are hard to cure. Treatment is usually palliative, to relieve symptoms and improve the quality of life. Patients with early stage disease may live many years.

For most people, mycosis fungoides is an indolent, chronic disease, but the course of mycosis fungoides for any one individual can be unpredictable.

It can be slow, rapid or static. mycosis fungoides almost never progresses to lymph nodes and internal organs without showing obvious signs of progression in the skin such as worsening ulcers or tumors, and examining the skin is a very important clue to possible internal disease.

There is no known cure for mycosis fungoides. Some patients have long-term remission with treatment, and many more live with minimal or no symptoms for many, many years. Research indicates that most patients diagnosed with mycosis fungoides live with early stage disease, and have a normal life span. With advances in research and new treatment options resulting from physician collaboration and clinical trials, mycosis fungoides patients are experiencing better care and an array of effective treatment options that work for them.

- Willemze R, Jaffe ES, Burg G, Cerroni L, Berti E, Swerdlow SH, et al. WHO-EORTC classification for cutaneous lymphomas. Blood. 2005;105:3768-85.[↩]

- Jansen, Patty & Willemze, Roel. (2015). Mycosis fungoides: diagnostic considerations. Hematology Education: the education program for the annual congress of the European Hematology Association 2015; 9(1), 297[↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Wohl Y, Tur E. Environmental risk factors for mycosis fungoides. Curr Probl Dermatol. 2007;35:52-64.[↩]

- Kim YH, Liu HL, Mraz-Gernhard S, Varghese A, Hoppe RT. Long-term outcome of 525 patients with mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome: clinical prognostic factors and risk for disease progression. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139:857-66.[↩]

- Ralfkiaer E, Cerroni L, Sander CA, Smoller BR, Willemze R. In: Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Pileri SA, Stein H, et al, (eds). WHO Classification of Tumours of Hematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. 4th ed. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2008:296-8.[↩]