Myiasis

Myiasis is the infestation of live vertebrates (humans and/or animals) with a fly larva (maggot) of various fly species within the arthropod order Diptera (two-winged adult flies), usually occurring in tropical and subtropical areas 1. The fly larvae feed on the host’s dead or living tissue, body substances, or ingested food.

There are several ways for flies to transmit their larvae to people 2:

- Some flies attach their eggs to mosquitoes and wait for mosquitoes to bite people. Their larvae then enter these bites.

- Other flies’ larvae burrow into skin. These fly larvae are known as screwworms. They can enter skin through people’s bare feet when they walk through soil containing fly eggs or attach themselves to people’s clothes and then burrow into their skin.

- Some flies deposit their larvae on or near a wound or sore, depositing eggs in sloughing-off dead tissue.

Myiasis can be categorized clinically based on the area of the body infested, for example cutaneous, ophthalmic, auricular, and urogenital 3. Cutaneous myiasis is myiasis affecting the skin. Cutaneous myiasis presentations include furuncular, migratory, and wound myiasis, depending on the type of infesting larvae.

Myiasis is rarely acquired in the United States; people typically get the fly larva (maggot) infection when they travel to tropical areas in Africa and South America. People traveling with untreated and open wounds are more at risk for getting myiasis.

The fly larvae need to be surgically removed by a medical professionall 2. Typically, the wound is cleaned daily after the fly larvae are removed. Proper hygiene of wounds is very important when treating myiasis. Sometimes medication is given, depending on the type of larva that causes the problem.

In which countries does myiasis occur?

Myiasis occurs in tropical and subtropical areas. These can include countries in Central America, South America, Africa, and the Caribbean Islands.

Is having myiasis common?

Myiasis is not common in the United States. Most people in the United States with myiasis got it when they traveled to tropical areas in Africa and South America. People with untreated and open wounds are more likely to get myiasis.

What should I do if I think I have myiasis?

Contact your health care provider for proper diagnosis and care.

Should I be concerned about spreading infection to the rest of my household?

No. Myiasis is not spread from person to person. The only way to get myiasis is through flies, ticks, and mosquitoes.

Myiasis causes

Myiasis is infection with the larval stage (maggots) of various flies. Flies in several genera may cause myiasis in humans. Dermatobia hominis is the primary human bot fly. Cochliomyia hominovorax is the primary screwworm fly in the New World and Chrysomya bezziana is the Old World screwworm. Cordylobia anthropophaga is known as the tumbu fly. Flies in the genera Cuterebra, Oestrus and Wohlfahrtia are animal parasites that also occasionally infect humans.

You may have gotten an infection from accidentally ingesting larvae, from having an open wound or sore, or through your nose or ears. People can also be bitten by mosquitoes, ticks, or other flies that harbor fly larvae. In tropical areas, where the fly larva (maggot) infection is most likely to occur, some flies lay their eggs on drying clothes that are hung outside.

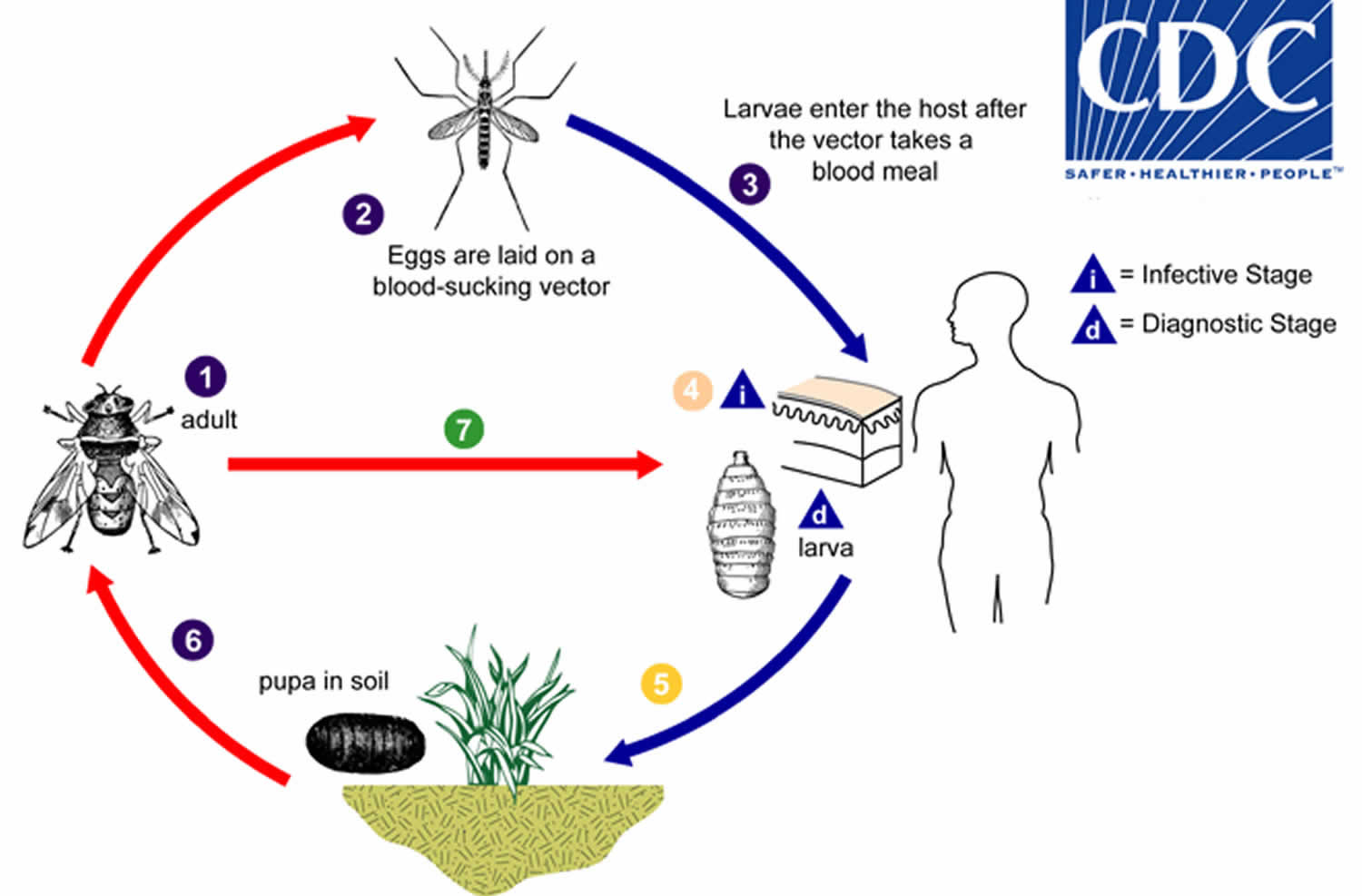

Myiasis life cycle

Adults of Dermatobia hominis are free-living flies (number 1). Adults capture blood-sucking arthropods (such as mosquitoes) and lay eggs on their bodies, using a glue-like substance for adherence (number 2). Bot fly larvae develop within the eggs, but remain on the vector until it takes a blood meal from a mammalian or avian host. Newly-emerged bot fly larvae then penetrate the host’s tissue (number 3). The larvae feed in a subdermal cavity (number 4) for 5-10 weeks, breathing through a hole in the host’s skin. Mature larvae drop to the ground (number 5) and pupate in the environment. Larvae tend to leave their host during the night and early morning, probably to avoid desiccation. After approximately one month, the adults emerge (number 6) to mate and repeat the cycle. Other genera of myiasis-causing flies (including Cochliomyia, Cuterebra, and Wohlfahrtia) have a more direct life cycle, where the adult flies lay their eggs directly in, or in the vicinity of, wounds on the host (number 7). In Cochliomyia and Wohlfahrtia infestations, larvae feed in the host for about a week, and may migrate from the subdermis to other tissues in the body, often causing extreme damage in the process.

Figure 1. Myiasis life cycle

Myiasis prevention

- Use window screens and mosquito netting, insect repellents and insecticides, adequate protective clothing, and good skin and wound hygiene to keep flies, mosquitoes, and ticks from reaching the skin.

- Cover open wounds and change dressings daily.

- Take extra care going to tropical areas and spending a lot of time outside. Cover your skin to limit the area open to bites from flies, mosquitoes, and ticks. Use insect repellant and follow Travelers Health guidelines (https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel).

- In areas where myiasis is known to occur, protect yourself by using window screens and mosquito nets.

- In tropical areas, iron any clothes that were put on the line to dry.

- In the case of Cordylobia anthropophaga, hang clothes to dry in bright sunlight and/or iron them (the heat destroys both the eggs and larvae)

- Improve hygiene and sanitation (e.g. remove rubbish from around living areas)

Myiasis symptoms

A lump will develop in tissue as the larva grows. Larvae under the skin may move on occasion. Usually larvae will remain under the skin and not travel throughout the body.

Cutaneous myiasis

Cutaneous myiasis is myiasis affecting the skin 3.

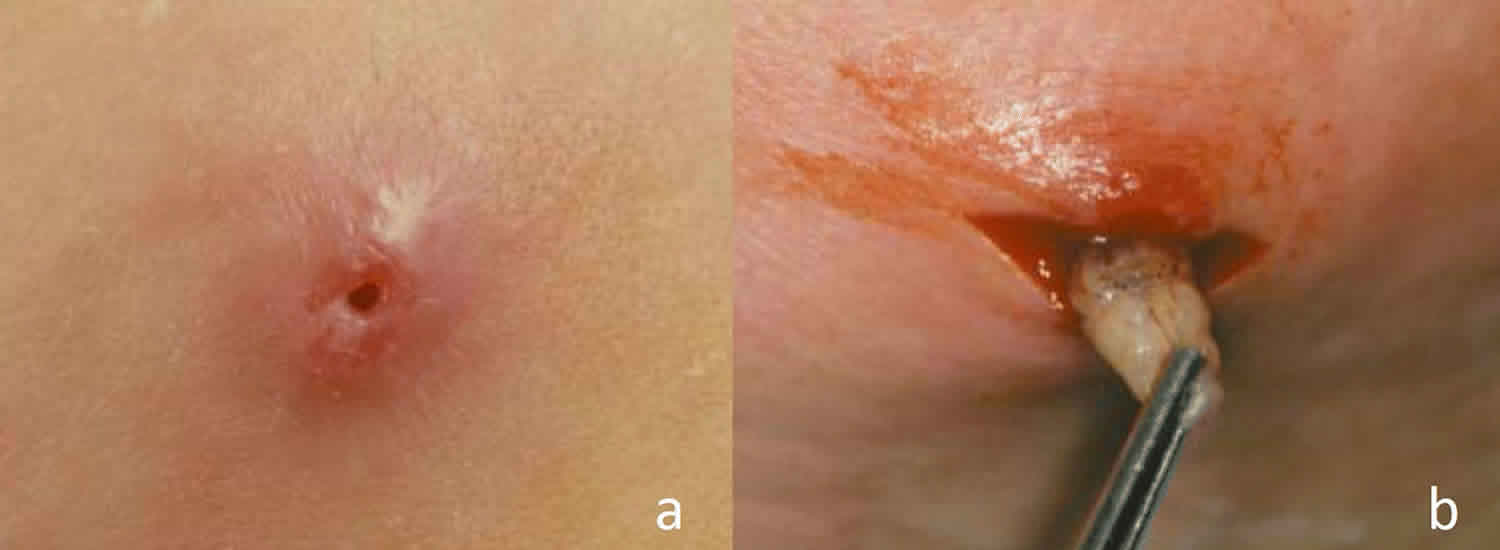

Furuncular myiasis

Dermatobia hominis

- Dermatobia hominis is found in Central and South America. The Dermatobia hominis female fly lays her eggs onto foliage or carrier insects, most commonly mosquitoes. The eggs are passed to humans by direct contact with foliage, or during a bite from the carrier.

- Once the eggs hatch, the larvae burrow painlessly into the host’s skin producing a small red papule (bump). The papule later becomes a furuncular-like (boil-like) nodule with a central pore through which the organism breathes. Occasionally the tail end of the larva can be seen through this pore.

- Over the following 5 to 10 weeks the larvae further develop and burrow deeper into the host’s skin, forming a dome-shaped cavity. Symptoms include itching, a sensation of movement, stabbing pain (often at night), and a serosanguinous (thin, yellow or bloody) discharge.

- The larvae eventually work their way back to the skin surface, then drop to the ground where they pupate to form flies.

- The lesions generally resolve with minimal scarring after the larvae emerge or are removed. The most important complications of Dermatobia hominis are bacterial super-infection (rare) and tetanus. Dermatobia hominis has caused fatal cerebral myiasis in infants due to infestation of the skin covering the fontanelles.

Cordylobia

- Cordylobia is found in tropical Africa. All three species of Cordylobia can cause furuncular myiasis, however Cordylobia anthropophaga is most commonly responsible.

- These flies prefer shade and usually lay their eggs on objects contaminated with urine or feces, such as sandy soil or damp clothing laid to dry on the ground.

- The eggs hatch in 1-3 days and the larvae can survive for up to 2 weeks while waiting to come into contact with a host. The larvae then painlessly penetrate the unbroken skin of the host. They develop over 8-12 days. Following this they emerge from the skin, fall to the ground, and pupate.

- Symptoms develop within the first 2 days of infestation and can range from a ‘prickly heat’ sensation to severe pain. Agitation and insomnia can also occur. Furuncular lesions with surrounding inflammation rapidly develop over a period of 6 days after symptoms begin. In the late stages, the tail end of the larvae may sometimes be seen in the central pore, and may withdraw when touched.

- If there are multiple sites of infestation, hosts may develop enlarged lymph nodes and fever. If lesions are numerous, they may coalesce forming large plaques with a serous (thin, yellow) discharge.

Cuterebra species

- Cuterebra is found in parts of North America. Human Cuterebra infestation is rare as the usual hosts are rodents, rabbits, and squirrels.

- Cuterebra eggs are laid near their usual hosts on grass or brush. Humans likely inadvertently contact the eggs, which then hatch, and larvae enter the host through the skin or mucous membranes of the nose, eyes, mouth, or anus.

- Almost all human cases present in August, September, or October.

- The typical lesion is a 2-20mm red papule or nodule with a central pore, through which the organism breathes. The larva is occasionally visible through this pore. A serous, serosanguinous, or purulent (consisting of pus) discharge may occur. The lesions may be itchy or painful, and some patients experience a sensation of movement within the lesion.

Wohlfahrtia vigil and Wohlfahrtia opaca

- Wohlfahrtia vigil is found in parts of North America, Europe, Russia, and Pakistan. Wohlfahrtia opaca is found in parts of North America. Larvae from Wohlfahrtia vigil and Wohlfahrtia opaca cause furuncular myiasis in cats, dogs, rabbits, ferrets, mink, foxes, and humans. In nearly all hosts, infestations mostly occur in the very young, because the larvae are unable to penetrate adult skin.

- Females from both Wohlfahrtia species are most active in shaded areas, during the late afternoon hours. The larvae are dropped onto host skin, which they then penetrate. Within 24 hours furuncles form. The larvae develop over 4-12 days, then leave the skin, fall to the ground, and pupate.

- Most cases occur during the months of June to September.

Migratory myiasis

Gasterophilus intestinalis

- Gasterophilus intestinalis is the most frequent cause of human migratory (or creeping) myiasis and is found worldwide. Gasterophilus intestinalis is usually an intestinal parasite of horses and other equids.

- Humans are an accidental host and become infested by direct contact with eggs on the horse’s coat or eggs may be directly laid onto human skin. The larva initially produces a papule similar to furuncular myiasis. Then the larva burrows to the lower layers of the epidermis, causing an intensely itchy, snake-like, and raised red linear lesion that advances at one end and fades at the other as it searches for a place to develop. The lesion can extend up to 30 cm per day and can continue for several months. The infestation may end spontaneously with or without suppuration (formation of a purulent sore).

Hypoderma bovis and Hypoderma lineatum

- Hypoderma species usually infest cattle and are found in most locations in the northern hemisphere.

- Human infections are rare and usually occur in rural areas where cattle are raised. The eggs are laid on the hairs of the body, and larvae enter through the skin or the mucosa of the mouth. The larva migrates in the subcutaneous tissue, causing a slightly red, tender, and ill-defined 1-5 cm raised area. A ‘prickly’ sensation and, less frequently, burning and itch, are reported. After several hours to several days the redness subsides, leaving a yellow-pigmented patch, as the larva wanders to another location. A faint, irregular, palpable line connects the old area of redness with the newer one. The larva can migrate 2 to 30 cm per day. Most often, the larva eventually dies in the subcutaneous tissue.

- In around 1 out of 15 human cases, the subcutaneous larva penetrates the dermis and forms a slowly enlarging tender red nodule (warble). A central pore develops, through which the larva may be visible. The pore intermittently drains a serosanguinous discharge, that later becomes purulent. Itching becomes intense, and the larva then grows, exits, and falls to the ground to pupate.

- Human Hypoderma myiasis is usually a mild disease, but can cause fever, muscle pain, joint pain, scrotal swelling, ascites (fluid in the peritoneal cavity of the abdomen), fluid around the heart, and invasion of the brain and spinal cord.

Wound myiasis

Wound myiasis occurs when fly larvae infest open wounds in a living host. Mucous membranes (e.g. oral, nasal, and vaginal membranes) and body cavity openings (e.g. in or around the ears and eye socket) can also be affected. Severe cases may be accompanied by fever, chills, pain, bleeding from the infested site, and secondary infection. Blood tests may show raised neutrophils and eosinophils. Massive tissue destruction, the loss of eyes and ears, erosion of bones and nasal sinuses, and death can occur.

Factors that make humans susceptible to wound myiasis include poor social conditions, poor hygiene, advanced or very young age, psychiatric illness, alcoholism, diabetes, peripheral vascular disease, poor dental hygiene, and physical disabilities that restrict ability to discourage flies.

Cochliomyia hominivorax

Cochliomyia hominivorax is found in Central and South America. In humans, infestations of Cochliomyia hominivorax usually occur in or around the ears, nose and eye socket. Even tiny wounds such as a tick bite or an ingrown toenail can attract Cochliomyia hominivorax. The female lays her eggs on the edges of wounds or healthy mucous membranes. Within one day the eggs hatch and the larvae feed on tissue causing massive tissue destruction and large deep lesions. An odor is produced which attracts more female flies to lay additional batches of eggs. A single wound can contain up to 3000 larvae, which eventually fall to the ground to pupate.

Chrysomya bezziana

Chrysomya bezziana is found in Africa, India, and Southeast Asia. The life cycle and biologic activity of Chrysomya bezziana is similar to that of Chrysomya hominivorax. As these larvae burrow deeper into host tissue, only the black tail ends are seen. Chrysomya bezziana infests wounds, areas of soft skin, and mucous membranes. The only presenting features of a nasal sinus infestation may be a swollen face associated with headaches, fever, burning nasal pain, and a nasal discharge.

Wohlfahrtia magnifica

Wohlfahrtia magnifica is found in parts of Europe, Russia, North Africa, and the Middle East. Adult Wohlfahrtia magnifica flies are active in the summer months during the warmest part of the day. In humans, wounds, ears, eyes, and nasal passages are commonly infested. Wohlfahrtia magnifica larvae are usually less destructive than Chrysomya bezziana and Chrysomya hominivorax.

Oral myiasis

Oral myiasis, first described in the literature in 1909, is a kind of wound myiasis associated with poor oral hygiene 4, alcoholism 5, senility 6, severe halitosis 7, socket orifice 8, suppurating lesions, gingival disease, trauma, and mental debility 9 and with people who maintain their mouths open for a long period of time 8. Infants who were breastfed by mothers with breasts infected by Cordylobia anthropophaga presented with larvae in the upper and lower lips and in other parts of the body 10. Poor hygiene is the most important risk factor and is present in almost all cases 11.

The infestation of the oral cavity may occur through direct infestation in cases where the lesions are at the anterior mandibular or maxillary region 7. Infestation into the buccal gingiva of the mandibular molar region supports the possibility by which the ingestion of contaminated food may be the way of transmission 11.

Species reported to cause this clinical picture are Cochliomyia hominivorax 7, Wohlfahrtia magnifica 11, Musca domestica 12, Chrysomya bezziana 13, Oestrus ovis 14, Hypoderma bovis 15, Hypoderma tarandi 16, Musca nebulo 8, Gasterophilus intestinalis 17, and Calliphora vicina 18.

Extensive tissue destruction may follow infection, and palatal perforation is a possible complication 9.

Oral myiasis symptoms

Pain and swelling of the mouth, the teeth, the lips, or the palates and a sensation of movement are some of the reported symptoms related to oral myiasis. In one case, the larva died in the submucosa and manifested clinically like a salivary gland adenoma 19.

Oral myiasis diagnosis

The diagnosis of oral myiasis is usually easy and should be made at an early stage so that an involvement of deeper tissues can be prevented. This is especially important for individuals with a low socioeconomic status, who may be unaware of the oral lesions 20. Moreover, a lack of regular oral care in these patients may cause the lesions to go unnoticed until extensive tissue involvement occurs. Destructive complications are possible, and a CT scan should be performed when those complications are suspected 21.

Oral myiasis treatment

The treatment of oral myiasis is ideally done by the surgical removal of the maggots 11. An alternative treatment for myiasis is the creation of an anaerobic environment inside the wound to kill or expulse the maggots. Turpentine solution may help the extraction of maggots 8. The use of drugs to treat oral myiasis is incipient, and few reports can be found 21. Nitrofurazone (0.2%; 20 ml) topically applied over the infested wound 3 times per day during 3 days proved to be successful in two cases 22. Treatment with ivermectin with a partial or complete response was reported 9. Prompt and correct management may lower the complication rate of oral myiasis 23.

Ocular myiasis

Ocular myiasis also known as ophthalmomyiasis, or oculomyiasis, is the infestation of any anatomic structure of the eye 24. This group is further subclassified into superficial ocular myiasis or ophthalmomyiasis externa and deep ocular myiasis or ophthalmomyiasis interna. Orbital myiasis, or “ophtalmomyiase profonde” (French term meaning profound or deep) is used to bring together palpebral or periocular infestation with intraocular myiasis.

Superficial ocular myiasis

Ophthalmomyiasis externa refers to the superficial infestation of ocular tissue. Conjunctival myiasis is the most common form of ophthalmomyiasis, and it is a relatively mild, self-limited, and benign disease. Patients commonly complain of acute foreign-body sensation with lacrimation, characteristically with an abrupt onset 25. Upon examination, unilateral disease is the rule. The movement of the larva may be felt by the patient 26. In response to the movement of the larva across the external surface of the eyeball 27, any of the following symptoms may be found upon an ophthalmologic examination 28:

- red eye,

- photophobia,

- conjunctival hyperemia,

- lid edema,

- punctate conjunctival hemorrhages,

- pseudomembrane formation, and

- superficial punctate keratopathy.

Lachrymal gland myiasis may complicate conjunctival infestation, and a canalicular lesion may also follow external ocular myiasis (297). Migration through the lacrimal canal to the nose cavity is a possibility 29. Mild pain and inflammation usually last for 10 days.

Ocular myiasis should be considered in any case of unilateral foreign body sensation with a marked onset. Other differential diagnoses of this clinical picture include catarrhal conjunctivitis, keratitis (324), periorbital or preseptal cellulitis 30, keratouveitis 31, and chalazion 32.

Oestrus ovis is the main agent causing external ocular myiasis, and as expected, the cases are usually described to occur in the autumn months in cooler latitudes of the northern and southern hemispheres, especially in rural areas. The majority of cases have been described in the Mediterranean basin and Middle East (49,78, 94, 158, 174, 331). Other agents implicated in this form of disease are Rhinoestrus purpureus 33, Dermatobia hominis 34, Chrysomya bezziana 35, Lucilia spp. 36, and Cuterebra 37.

External manifestations are managed by the mechanical removal of larvae from the surface of the anesthetized eyeball, using fine, nontoothed forceps. Slit-lamp examination facilitates the process, but viable larvae have the tendency to avoid bright light. The use of lidocaine or cocaine as an anesthetic has the additional benefit of maggot immobilization, which facilitates removal. Occlusion with a thick ointment may assist in removal by encouraging the egress of organisms from the conjunctival sac, if it is involved. The average number of extracted parasites varies from 9 to

18. One case was successfully treated with ivermectin 38.

Deep ocular myiasis

Ophthalmomyiasis interna is a term used when the infestation involves the anterior or posterior segment of the eyeball. The fly larva may be seen in the anterior segment and the vitreous and subretinal space 39. This clinical picture may be a complication of ophthalmomyiasis externa 40. However, the entry site is usually not apparent; these larvae probably penetrate the sclera and migrate into the eye. Usually, there is only one larva inside the eye; however, two to three larvae in the same eye and bilateral involvement have also been reported 41.

Anterior ophthalmomyiasis interna is less common and appears clinically as anterior uveitis, sometimes accompanied by posterior segment inflammation, which may be severe 42.

In its classical clinical presentation, posterior ophthalmomyiasis interna is characterized by pigmented and atrophic retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) tracts in a crisscrossing pattern seen in conjunction with hemorrhages, fibrovascular proliferation, exudative detachment of the retina, and even fibrovascular scarring 43. Subretinal myiasis can cause exudative and fibrovascular detachments and even focal hemorrhages, multifocal fibrous scarring, total detachment, and blindness 44. However, its typical clinical manifestation is that of multiple-crisscross retinal pigment epithelium with atrophic pigmentary tracts 45. Only a few other agents have been reported to produce a subretinal tract 46.

Red eye, vision loss, floaters, eye pain, and scotomas are the symptoms that have been described for ophthalmomyiasis interna. Vision loss can be severe and is more commonly associated with Hypoderma tarandi. Ophthalmomyiasis interna should be considered for the differential diagnosis of retinal detachment, panuveitis 47, orbital cellulitis 48, cavernous sinus thrombosis 49, chorioretinitis 50, and endophthalmitis 51.

Accordingly, the diagnosis of subretinal myiasis is made on the basis of sub-retinal pigment epithelium tracts and the typical clinical morphological changes known to be characteristic of ophthalmomyiasis interna. The fly larva, which is 10 to 20 mm in size, has a cigar-shaped appearance, with multiple skeletal braces. Hemorrhage may occur as the fly larva erodes through vascular tissue; choroidal neovascularization may also occur, with exudative hemorrhagic detachment and eventual fibrovascular scarring.

The epidemiologic data concerning ophthalmomyiasis interna are not precise, because in many cases, the larva is destroyed by laser photocoagulation. The reindeer or caribou warble fly Hypoderma species are considered the most common cause, with Hypoderma tarandi being the most frequent cause in northern European countries such as Norway 52.

Orbital myiasis

Orbital myiasis has a severe clinical picture characterized by the intraocular invasion of maggots from eyelid myiasis, a peculiar kind of wound myiasis. Eyelid tumors are the most common predisposing factor associated with this clinical picture 53, although it may affect a previously healthy individual. Causative agents are the same as those that cause wound myiasis and vary with the geographical distribution of the flies.

The management of internal infestation is more variable and highly dependent on the clinical situation. Dead larvae, without significant inflammation, may be left in place and eventually regress. Inflammation requires management with topical steroids and mydriatics, with close monitoring. The presence of persistently viable larvae may require surgical removal, particularly when critical structures are at risk. Living organisms in the appropriate location, such as the subretinal space, may be amenable to destruction by laser photocoagulation 48. In extensive orbital myiasis, exenteration is needed to prevent the intracranial extension of tissue destruction 54. Ivermectin is a therapeutic option to prevent the further extension of the necrotizing process into deeper structures and, therefore, to decrease the risk of lethal outcomes and the need for enucleation 55.

Intestinal myiasis

Intestinal myiasis is a kind of pseudomyiasis or accidental myiasis that is probably related to the ingestion of contaminated food or water with dipteran fly larvae 56. Poor socioeconomic status and poor hygiene are risk factors. The water supply is a possible contamination source 57. The female flies may oviposit the eggs around the mouth of comatose and psychiatric patients, and any patient who sleeps or keeps the mouth open is also prone to gastrointestinal infestation.

The clinical presentation is variable and depends on the number of maggots, the species of the parasite, and their location within the digestive tract. Symptoms range from asymptomatic cases, where the larvae are identified in the stools, to abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, anal pruritus, or rectal bleeding 58. The presence of the maggots may cause an inflammation of the intestinal mucosa and justify the symptoms. In some cases, the origin of the symptoms may be confusing, because patients may have a concomitant parasitic enteric infection, such as Ascaris lumbricoides 59, or antiparasitic drugs [albendazole 58 or mebendazole 60] may have been used before the diagnosis of pseudomyiasis. On the other hand, the relief of symptoms after the elimination of the maggots is incontestable proof that intestinal myiasis may be responsible for these symptoms 61.

The presence of numerous larvae in one or more consecutive stool specimens is diagnostic. Ideally, the sample should be collected in the laboratory so that a posterior infestation of the stool can be ruled out. Maggot identification from specimens collected by sigmoidoscopy is more reliable if external contamination is suspected 62.

Myiasis agents associated with this type of accidental myiasis are Fannia canicularis 63, Sarcophaga spp., Hermetia illucens 59, Muscina stabulans, Megaselia scalaris 64, Eristalis tenax 65, Musca domestica, Phormia regina 66, Lucilia cuprina 67, and Stomoxys calcitrans 56.

Even though no specific treatment is valid for the treatment of intestinal myiasis, purgatives, albendazole, mebendazole, and levamizole were reported to cure the disease in some patients. Mesalazine has been used as an anti-inflammatory agent. Colonoscopy may have diagnostic and therapeutic functions 68.

Myiasis treatment

Fly larvae need to be surgically removed 69. No medications approved by the FDA are available for treatment.

Preventing possible exposure is key advice for patients traveling in tropical areas of Africa and South America. Those with untreated and open wounds are more at risk.

Occlusion

- The fly maggots require contact with air to breathe. Occlusion either kills the fly larva or induces it to move upwards, where it can be removed.

- A variety of occlusive substances have been used, including petrolatum, animal fat, beeswax, paraffin, hair gel, mineral oil, and bacon. The occlusive substance is placed over the pore of the furuncle, or over the area of wound myiasis, for up to 24 hours.

- Once the fly maggots have migrated to the skin surface, they can be removed with forceps. This can be difficult as the larvae resist extraction using their spines to anchor themselves to the host. Dermatobia hominis is the most difficult larva to extract due to its tapered shape.

- Occasionally the fly larva is asphyxiated without emerging. The retained larva can cause an inflammatory response, leading to foreign body granuloma formation (a clump of inflammatory tissues) that may progress to calcification.

Larvicides

- Ivermectin is a broad-spectrum antiparasitic agent that may kill larvae, or at least cause them to migrate out of the skin. Ivermectin can be administered topically or as an oral dose.

- Mineral turpentine can be effective against Chrysomya larvae and may aid their removal in cases of wound myiasis.

- Ethanol spray and oil of betel leaf can be used topically to treat Cochliomyia hominivorax myiasis.

Manual removal of larvae

Furuncular myiasis

- A surgical incision is made. The larva is then removed with forceps. Care is taken to avoid damaging the larva, as retained parts can lead to a severe inflammatory reaction. Anaesthetising the larva with local anaesthetic may prevent it from anchoring its spines.

- Alternatively, local anaesthetic is injected forcibly into the base of the lesion in an attempt to create enough fluid pressure to push the larva out of the pore.

- A commercial vacuum snake venom extractor may also be used to suck the larva out.

- Traditional methods of larvae removal involve squeezing the skin surrounding the furuncle with fingers or with wooden spatulas.

- Hypoderma myiasis can be treated using these methods if a warble has formed.

Migratory myiasis

- Hypoderma larvae can be extracted through a surgical incision if there is no warble formation, but can be difficult to capture.

- Gasterophilus can be extracted by making a small surgical incision over the leading edge of the advancing lesion and using the tip of a sterile needle to remove.

Wound myiasis

Manual removal followed by irrigation is used to treat wound myiasis. Surgery may be necessary to remove dead host tissue.

- Fabio Francesconi, Omar Lupi. Clinical Microbiology Reviews Jan 2012, 25 (1) 79-105; DOI: 10.1128/CMR.00010-11 https://cmr.asm.org/content/cmr/25/1/79.full.pdf[↩]

- Parasites – Myiasis. https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/myiasis[↩][↩]

- Cutaneous myiasis. https://dermnetnz.org/topics/cutaneous-myiasis/[↩][↩]

- Lata J, Kapila BK, Aggarwal P. 1996. Oral myiasis—a case report. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 25:455– 456.[↩]

- Fonseca DR, et al. 2007. Miasis buco-maxilo-facial: reporte de un caso. Acta Odontol. Venez. 45:565–567.[↩]

- Gonzalez MM, Comte MG, Monardez PJ, Diaz de Valdes LM, Matamala CI. 2009. Accidental genital myiasis by Eristalis tenax. Rev. Chilena Infectol. 26:270 –272.[↩]

- Barbosa TD, Rocha R, Guirado CG, Rocha FJ, Gaviao MBD. 2008. Oral infection by Diptera larvae in children: a case report. Int. J. Dermatol. 47:696–699.[↩][↩][↩]

- Sharma J, Mamatha GP, Acharya R. 2008. Primary oral myiasis: a case report. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal. 13:E714 –E716.[↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Gealh WC, Ferreira GM, Farah GJ, Teodoro U, Camarini ET. 2009. Treatment of oral myiasis caused by Cochliomyia hominivorax: two cases treated with ivermectin. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 47:23–26.[↩][↩][↩]

- Ollivier FJ, et al. 2006. Pars plana vitrectomy for the treatment of ophthalmomyiasis interna posterior in a dog. Vet. Ophthalmol. 9:259 –264.[↩]

- Droma EB, et al. 2007. Oral myiasis: a case report and literature review. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endod. 103:92–96.[↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Bhatt AP, Jayakrishnan A. 2000. Oral myiasis: a case report. Int. J. Paediatr. Dent. 10:67–70.[↩]

- Ng KH, et al. 2003. A case of oral myiasis due to Chrysomya bezziana. Hong Kong Med. J. 9:454–456.[↩]

- Hakimi R, Yazdi I. 2002. Oral mucosa myiasis caused by Oestrus ovis. Arch. Iran. Med. 5:194 –196.[↩]

- Erol B, Unlu G, Balci K, Tanrikulu R. 2000. Oral myiasis caused by Hypoderma bovis larvae in a child: a case report. J. Oral Sci. 42:247–249.[↩]

- Faber TE, Hendrikx WML. 2006. Oral myiasis in a child by the reindeer warble fly larva Hypoderma tarandi. Med. Vet. Entomol. 20:345–346.[↩]

- Townsend LH, Hall RD, Turner EC. 1978. Human oral myiasis in Virginia caused by Gasterophilus intestinalis (Diptera: Gasterophilidae). Proc. Entomol. Soc. Wash. 80:129 –130.[↩]

- Gursel M, Aldemir OS, Ozgur Z, Ataoglu T. 2002. A rare case of gingival myiasis caused by Diptera (Calliphoridae). J. Clin. Periodontol. 29:777–780.[↩]

- Kamboj M, Mahajan S, Boaz K. 2007. Oral myiasis misinterpreted as salivary gland adenoma. J. Clin. Pathol. 60:848.[↩]

- Philip J, Matthews R, Scipio JE. 2007. Larvae in the mouth. Br. Dent. J. 203:174 –175.[↩]

- Shinohara EH, Martini MZ, de Oliveira Neto HG, Takahashi A. 2004. Oral myiasis treated with ivermectin: case report. Braz. Dent. J. 15: 79–81.[↩][↩]

- Lima Junior SM, Asprino L, Prado AP, Moreira RW, de Moraes M. 2010. Oral myiasis caused by Cochliomyia hominivorax treated nonsurgically with nitrofurazone: report of 2 cases. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endod. 109:e70–e73.[↩]

- Arora S, Sharma JK, Pippal SK, Sethi Y, Yadav A. 2009. Clinical etiology of myiasis in ENT: a reterograde period—interval study. Braz. J. Otorhinolaryngol. 75:356 –361.[↩]

- Myiasis. Clinical Microbiology Reviews p. 79–105 https://cmr.asm.org/content/cmr/25/1/79.full.pdf[↩]

- Anane S, Hssine LB. 2010. Conjonctival [sic] human myiasis by Oestrus ovis in southern Tunisia. Bull. Soc. Pathol. Exot. 103:299 –304.[↩]

- Otranto D, Cantacessi C, Santantonio M, Rizzo G. 2009. Oestrus ovis causing human ocular myiasis: from countryside to town centre. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 37:327–328.[↩]

- Amr ZS, Amr BA, Abo-Shehada MN. 1993. Ophthalmomyiasis externa caused by Oestrus ovis L. in the Ajloun area of northern Jordan. Ann. Trop. Med. Parasitol. 87:259 –262.[↩]

- Chandra DB, Agrawal TN. 1981. Ocular myiasis caused by oestrus ovis. (A case report.) Indian J. Ophthalmol. 29:199 –200.[↩]

- Eyigor H, Dost T, Dayanir V, Basak S, Eren H. 2008. A case of naso-ophthalmic myiasis. Kulak Burun Bogaz Ihtis. Derg. 18:371–373.[↩]

- Engelbrecht NE, Yeatts RP, Slansky F. 1998. Palpebral myiasis causing preseptal cellulitis. Arch. Ophthalmol. 116:684.[↩]

- Jenzeri S, et al. 2008. External ophthalmomyiasis manifesting with keratouveitis. Int. Ophthalmol. 29:533–535.[↩]

- Wilhelmus KR. 1986. Myiasis palpebrarum. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 101: 496–498.[↩]

- Ducournau D, Bonnet M. 1982. Posterior internal ophthalmomyiasis. Bull. Soc. Ophtalmol. Fr. 82:1529 –1530.[↩]

- De Tarso P, Pierre P, Minguini N, Pierre LM, Pierre AM. 2004. Use of ivermectin in the treatment of orbital myiasis caused by Cochliomyia hominivorax. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 36:503–505.[↩]

- Caca I, Satar A, Unlu K, Sakalar YB, Ari S. 2006. External ophthalmomyiasis infestation. Jpn. J. Ophthalmol. 50:176 –177.[↩]

- Huynh N, Dolan B, Lee S, Whitcher JP, Stanley J. 2005. Management of phaeniciatic ophthalmomyiasis externa. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 89: 1377–1378.[↩]

- Feder HM, Mitchell PR, Seeley MZ. 2003. A warble in Connecticut. Lancet 361:1952.[↩]

- Wakamatsu TH, Pierre-Filho PTP. 2006. Ophthalmomyiasis externa caused by Dermatobia hominis: a successful treatment with oral ivermectin. Eye 20:1088 –1090.[↩]

- Jakobs EM, Adelberg DA, Lewis JM, Trpis M, Green WR. 1997. Ophthalmomyiasis interna posterior. Report of a case with optic atrophy. Retina 17:310 –314.[↩]

- Wolfelschneider P, Wiedemann P. 1996. External ophthalmic myiasis cause by Oestrus ovis (sheep and goat botfly). Klin. Monbl. Augenheilkd. 209:256 –258.[↩]

- Mason GI. 1981. Bilateral ophthalmomyiasis interna. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 91:65–70.[↩]

- Saraiva VS, Amaro MH, Belfort R Jr, Burnier MN Jr. 2006. A case of anterior internal ophthalmomyiasis: case report. Arq. Bras. Oftalmol. 69:741–743.[↩]

- Slusher MM, Holland WD, Weaver RG, Tyler ME. 1979. Ophthalmomyiasis interna posterior. Subretinal tracks and intraocular larvae. Arch. Ophthalmol. 97:885– 887.[↩]

- Syrdalen P, Nitter T, Mehl R. 1982. Ophthalmomyiasis interna posterior: report of case caused by the reindeer warble fly larva and review of previous reported cases. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 66:589–593.[↩]

- Lima LH, et al. 2010. Ophthalmomyiasis with a singular subretinal track. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 150:731.e1–736.e1.[↩]

- Biswas J, Gopal L, Sharma T, Badrinath SS. 1994. Intraocular Gnathostoma spinigerum. Clinicopathologic study of two cases with review of literature. Retina 14:438–444.[↩]

- Khoumiri R, et al. 2008. Ophthalmomyiasis interna: two case studies. J. Fr. Ophtalmol. 31:299 –302.[↩]

- Georgalas I, Ladas I, Maselos S, Lymperopoulos K, Marcomichelakis N. 2011. Intraocular safari: ophthalmomyiasis interna. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 39:84–85.[↩][↩]

- Alves CA, Ribeiro O Jr, Borba AM, Ribeiro AN, Guimaraes J, Jr. 2010. Cavernous sinus thrombosis in a patient with facial myiasis. Quintessence Int. 41:e72– e74.[↩]

- Olumide YM. 1994. Cutaneous myiasis: a simple and effective technique for extraction of Dermatobia hominis larvae. Int. J. Dermatol. 33: 148–149.[↩]

- Gozum N, Kir N, Ovali T. 2003. Internal ophthalmomyiasis presenting as endophthalmitis associated with an intraocular foreign body. Ophthalmic Surg. Lasers Imaging 34:472– 474.[↩]

- Buettner H. 2002. Ophthalmomyiasis interna. Arch. Ophthalmol. 120:1598–1599.[↩]

- Baliga MJ, Davis P, Rai P, Rajasekhar V. 2001. Orbital myiasis: a case report. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 30:83– 84.[↩]

- Yeung JC, Chung CF, Lai JS. 2010. Orbital myiasis complicating squamous cell carcinoma of eyelid. Hong Kong Med. J. 16:63– 65.[↩]

- Osorio J, et al. 2006. Role of ivermectin in the treatment of severe orbital myiasis due to Cochliomyia hominivorax. Clin. Infect. Dis. 43:e57– e59.[↩]

- Ferreira MF, et al. 1990. Intestinal myiasis in Macao. Zhongguo Ji Sheng Chong Xue Yu Ji Sheng Chong Bing Za Zhi 8:214 –216.[↩][↩]

- Kun M, Kreiter A, Semenas L. 1998. Gastrointestinal human myiasis for Eristalis tenax. Rev. Saude Publica 32:367–369.[↩]

- Karabiber H, Oguzkurt DG, Dogan DG, Aktas M, Selimoglu MA. 2010. An unusual cause of rectal bleeding: intestinal myiasis. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 51:530 –531.[↩][↩]

- Calderón-Arguedas O, Murillo Barrantes J, Solano ME. 2005. Enteric myiasis by Hermetia illucens (Diptera: Stratiomyidae) in a geriatric patient of Costa Rica. Parasitol. Latinoam. 60:162–164.[↩][↩]

- Tu WC, Chen HC, Chen KM, Tang LC, Lai SC. 2007. Intestinal myiasis caused by larvae of Telmatoscopus albipunctatus in a Taiwanese man. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 41:400–402.[↩]

- Delhaes L, et al. 2001. Human nasal myiasis due to Oestrus ovis. Parasite 8:289 –296.[↩]

- Sehgal R, et al. 2002. Intestinal myiasis due to Musca domestica: a report of two cases. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 55:191–193.[↩]

- Yang ZR, Bao DW, Liang XY. 2005. Gastric myiasis caused by the larvae of Fannia canicularis. Zhongguo Ji Sheng Chong Xue Yu Ji Sheng Chong Bing Za Zhi 23:216.[↩]

- Mazayad SA, Rifaat MM. 2005. Megaselia scalaris causing human intestinal myiasis in Egypt. J. Egypt. Soc. Parasitol. 35:331–340.[↩]

- Dubois E, Durieux M, Franchimont MM, Hermant P. 2004. An unusual case in Belgium of intestinal myiasis due to Eristalis tenax. Acta Clin. Belg. 59:168 –170.[↩]

- Kenney M, Eveland LK, Yermakov V, Kassouny DY. 1976. Two cases of enteric myiasis in man—pseudomyiasis and true intestinal myiasis. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 66:786 –791.[↩]

- Morris AJ, Berry MA. 1996. Intestinal myiasis with Phaenicia cuprina. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 91:1290.[↩]

- Karabiber H, Oguzkurt DG, Dogan DG, Aktas M, Selimoglu MA. 2010. An unusual cause of rectal bleeding: intestinal myiasis. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 51:530–531.[↩]

- Guerrant RL, Walker DH, and Weller PE. Tropical Infectious Diseases: Principles, Pathogens, and Practice, pp. 1371-3, 2006.[↩]