Neonatal hemochromatosis

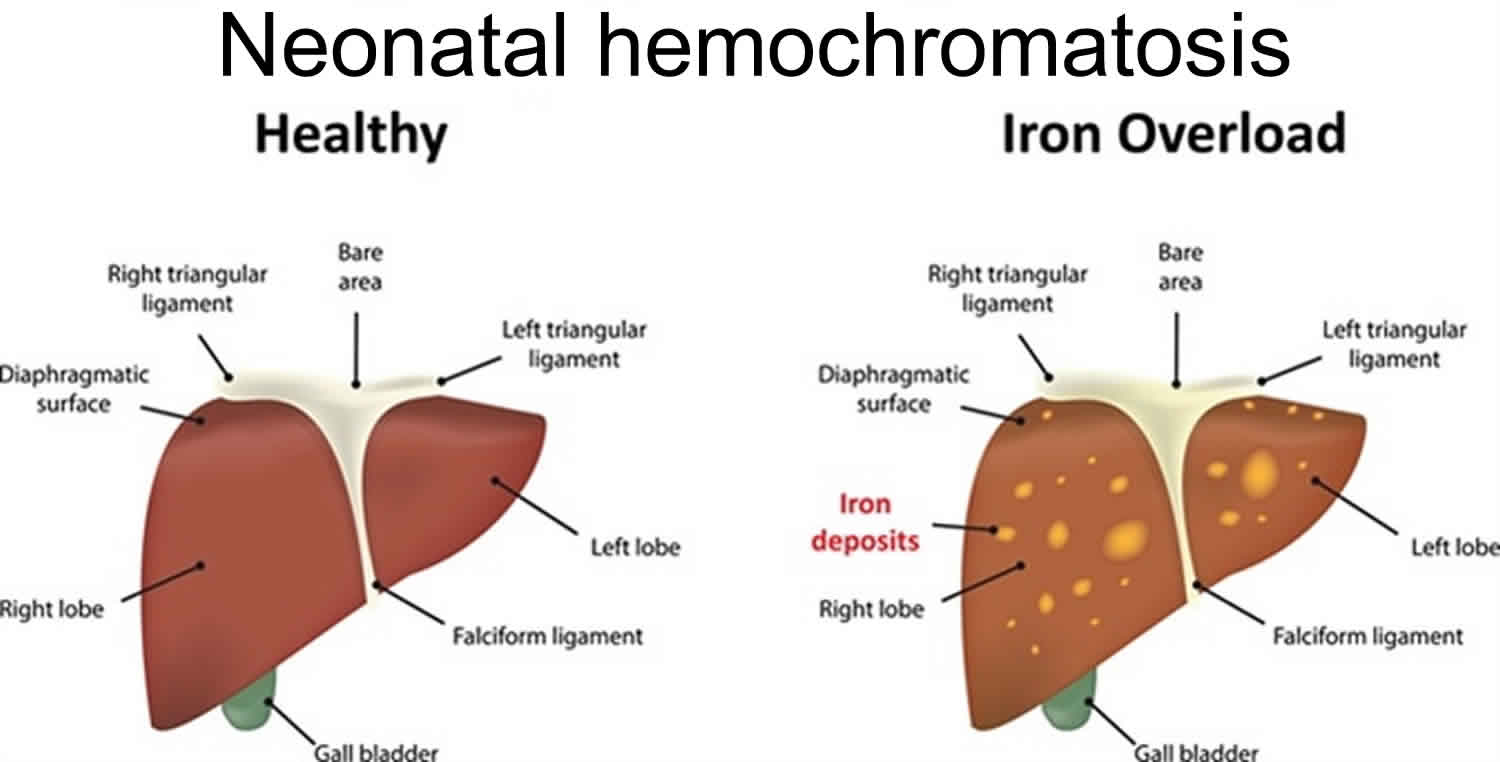

Neonatal hemochromatosis or neonatal haemochromatosis, is a syndrome of severe liver disease in which too much iron builds up in the liver and other body organs and can cause liver damage in fetuses and newborns 1. Neonatal hemochromatosis represents disordered iron handling due to injury to the perinatal liver and can be thought of as a form of fulminant hepatic failure 2. In neonatal hemochromatosis, the iron overload begins before birth. Neonatal hemochromatosis is thought to occur with damage to the liver at 16-30 weeks’ gestation 3. Neonatal hemochromatosis tends to progress rapidly and is characterized by liver damage that is apparent at birth or in the first days of life 4. Babies with neonatal hemochromatosis may be born very early (premature) or struggle to grow in the womb (intrauterine growth restriction). Symptoms of neonatal hemochromatosis may include low blood sugar (hypoglycemia), abnormalities in blood clotting, yellowing of the skin and eyes (jaundice), and swelling (edema) 5.

Some severe cases of neonatal haemochromatosis result in stillbirth, while live born infants with neonatal hemochromatosis typically show signs within 48 hours of birth. Neonatal hemochromatosis often produces life-threatening complications such as liver failure. However, some infants are less severely affected than others. There is a high risk of recurrence in subsequent pregnancies of women who have had a child with neonatal hemochromatosis.

Neonatal hemochromatosis is not a single disorder but is a syndrome with an unclear cause 6. It is thought that neonatal hemochromatosis may be caused by maternal fetal alloimmunity where a pregnant woman’s immune system recognizing cells of the baby’s liver as foreign and her antibodies travel over the placenta and mistakenly attack the fetus. A woman who has a child with neonatal hemochromatosis has approximately an 80 percent chance of having another child with the disorder. This pattern of recurrence cannot be explained by normal inheritance patterns. Thus, neonatal hemochromatosis appears to be congenital and familial, but not inherited.

Neonatal hemochromatosis is a disorder that affects males and females in equal numbers. The exact incidence of the disorder is unknown 7. Neonatal hemochromatosis has been documented in Filipino, African American, Hong Kong Chinese, and white infants. Neonatal hemochromatosis is the most common cause of liver failure in newborns and the most common reason for a liver transplant in newborns.

A diagnosis of neonatal hemochromatosis is suspected when a doctor observes signs and symptoms of hemochromatosis or liver disease in a newborn. A doctor may decide to order laboratory tests including a liver biopsy, MRI, or blood test 5.

Treatment options after birth requires supportive care which may include blood exchange transfusion, intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) therapy, and liver transplant 5. Survival rates in babies who undergo liver transplantation is reportedly 50% 8. Exchange transfusions and intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIG) have emerged as possible new treatments 9. Liver disease ascribed to hemosiderosis has not recurred in survivors to date.

Treatment after birth requires supportive care with or without administration of an iron-chelating cocktail and several antioxidants.

The prognosis is extremely poor. Some infants recover with supportive care, but this rarely occurs.

Suggest genetic counseling if the parents of a child with neonatal hemochromatosis desire to have another child. However, genetic patterns are unclear.

Neonatal hemochromatosis causes

The exact cause of neonatal hemochromatosis is not fully understood. There are two schools of thought: one hypothesizes that injury to the liver causes abnormal handling of iron by the liver; the other hypothesizes that the abnormal handling of iron by the liver leads to liver injury and failure.

Four pieces of evidence suggest that neonatal hemochromatosis may be due to an acquired and persistent maternal factor. First, neonatal hemochromatosis recurs within siblings at a rate higher than expected for disorders transmitted in an autosomal recessive manner. Second, several kindreds are known in which mothers have given birth to children with neonatal hemochromatosis who were fathered by different men.

Third, several kindreds are known in which parents of children with neonatal hemochromatosis had histories of exposure to blood with or without clinical hepatitis. Fourth, anecdotal evidence suggests that administering intravenous immunoglobulin during pregnancy in a woman who has already had an infant with neonatal hemochromatosis leads to a relatively favorable outcome.

These data suggest mitochondrial disease, transplacental transmission of an infective (possibly viral) agent, or transplacental transmission of an antibody as a cause of at least some instances of neonatal hemochromatosis. Because neonatal hemochromatosis is a syndrome, any of these possibilities may be correct in a given family, and all of them must be considered.

Significant evidence indicates that most cases of neonatal hemochromatosis result from fetal liver disease due to maternal fetal alloimmunity, a condition termed gestational alloimmune liver disease. A developing fetus is protected from foreign material (e.g., bacteria) by antibodies from its mother, which travel from the mother to the fetus through the placenta. Antibodies are specialized proteins that react against foreign material in the body bringing about their destruction. However, in materno-fetal alloimmune diseases, certain maternal antibodies mistakenly recognize some fetal cells or proteins, causing fetal injury. In gestational alloimmune liver disease, the fetal liver is targeted. Liver cells (hepatocytes) are damaged or killed by the antibody, and damage to the liver ultimately results in the abnormal accumulation of excess iron in the body and the symptoms of neonatal hemochromatosis.

Maternal fetal alloimmunity would explain the high recurrence rate of neonatal hemochromatosis in children of women who have already had a child with the disorder. Also, some women have had multiple children with neonatal hemochromatosis despite the children having different fathers, which would also be explained by maternal fetal alloimmunity.

Although maternal fetal alloimmunity would explain the majority of cases of neonatal hemochromatosis, rare cases may have a different cause. Neonatal hemochromatosis has been seen in association with genetic diseases including mitochondrial disease (DGUOK gene mutations), metabolic disease (bile acid synthetic defect) and chromosomal abnormalities (trisomy 21). More research is necessary to determine all of the causes and internal mechanisms that result in the development of neonatal hemochromatosis.

Neonatal hemochromatosis differential diagnoses

When liver failure is diagnosed in the first 1-2 days of life, neonatal hemochromatosis is by far the most common diagnosis. Afterward, many other conditions can manifest and must be excluded. They include all other causes of hepatic failure, including infective, metabolic, and hemorrhagic causes.

The following are other causes of liver failure in the newborn:

- Antenatal infection with adenovirus

- Coxsackievirus

- Alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency

- Hereditary fructose intolerance

- Maternofetal blood group incompatibility

- Hemoglobinopathy

- Hemophagocytic syndrome

- Inborn defects in erythrocyte membrane or enzymes

- Sepsis

- Ischemia or abnormal perfusion

- Extrahepatic biliary atresia

- Hepatic infarct

- Congenital leukemia

- Galactose-1-Phosphate Uridyltransferase Deficiency (Galactosemia)

- Parvovirus B19 Infection

- Pediatric Cytomegalovirus Infection

- Pediatric Echovirus

- Pediatric Hepatitis A

- Pediatric Hepatitis B

- Pediatric Hepatitis C

- Pediatric Rubella

- Pediatric Syphilis

- Pediatric Toxoplasmosis

- Tyrosinemia

All infants with a diagnosis of liver failure should undergo testing until a final diagnosis is reached.

Failure to diagnose neonatal hemochromatosis, resulting in the family having subsequent children with the same diagnosis.

Neonatal hemochromatosis symptoms

Neonatal hemochromatosis is characterized by liver disease that is present in the fetus or at birth (congenital). Damage to the liver occurs during pregnancy, ultimately leading to the abnormal accumulation of iron within tissue. Iron accumulation occurs while the fetus is developing in the womb and fetal loss late in pregnancy is common in families with a history of neonatal hemochromatosis. Growth delays within the womb (intrauterine growth deficiencies) are also common and many newborns are born prematurely.

Liver disease is usually apparent shortly after birth, although in rare cases it may not become apparent until days or weeks later. Symptoms of liver disease include low blood sugar (hypoglycemia), abnormalities in blood clotting (coagulopathy), yellowing of the skin and whites of the eyes (jaundice), decreased or absent urine production (oligouria) and swelling or puffiness due to fluid accumulation (edema), which may or may not occur in the abdomen (ascites). In many cases, scarring (cirrhosis), end stage liver disease and liver failure occur, sometimes within hours of birth. Iron accumulation may also occur in other organs including the pancreas, heart, thyroid, and salivary glands.

Forty percent of infants born with neonatal hemochromatosis are premature. Intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) occurs in 25% of infants with neonatal hemochromatosis.

Clues during pregnancy may indicate the diagnosis of neonatal hemochromatosis, but they are nonspecific. Oligohydramnios is frequently observed. Polyhydramnios is less commonly observed.

Neonatal hemochromatosis is considered a spectrum of disease with both severely affected and less severely affected infants. Some researchers speculate that some infants with neonatal hemochromatosis have no symptoms and the disorder may go undetected in such cases. In the medical literature, twins have developed neonatal hemochromatosis and one twin is severely affected while the other is only mildly affected.

The physical examination in the neonatal period is of little help but may reveal the following:

- Placental edema

- Intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR)

- Edema without ascites

- Oliguria

- Disseminated intravascular coagulation

- Jaundice in the first few days after birth

- Splenomegaly

Complications of the disease include liver failure, cardiac failure, respiratory failure, and disseminated intravascular coagulation.

Neonatal hemochromatosis diagnosis

A diagnosis of neonatal hemochromatosis should be suspected in any infants demonstrating liver disease before birth (antenatally) or shortly after birth. Blood tests may reveal elevated levels of ferritin in the blood serum, which may be indicative of liver disease and iron accumulation. Ferritin is an iron compound that is used as an indicator of the body’s iron stores.

A diagnosis of neonatal hemochromatosis may be confirmed based upon a thorough clinical evaluation, a detailed patient and family history, and a variety of specialized tests that can demonstrate the presence of excess iron in tissue outside the liver (extrahepatic siderosis). Surgical removal and microscopic evaluation of tissue (biopsy) can reveal excess iron. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), which uses a magnetic field and radio waves to produce cross-sectional images of particular organs and bodily tissues, can also be used to detect excess iron in tissue.

Laboratory tests

Relevant laboratory tests and findings include the following:

- Complete blood count (CBC) with differential – To check for anemia and thrombocytopenia

- Total and direct bilirubin levels – Elevated

- Reticulocyte count – To check for any signs of hemolysis

- Glucose level – Infants with neonatal hemochromatosis can present with hypoglycemia

- Albumin level – May be low, which accounts for the infants’ edema

- Urinalysis – To check for causes of oliguria and any renal involvement

- Blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine levels – To evaluate renal function

- Prothrombin time (PT), activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT), and fibrin split products – To rule out any hemorrhagic causes

- Transferrin level – Low but hypersaturated (one of the most common findings)

- Serum ferritin levels – Elevated

- Total iron-binding capacity – Low

- Cytoferrin level – Markedly elevated

- Lactic acid dehydrogenase (LDH) level – Markedly elevated

- Aminotransferases level – Mildly elevated

- Iron levels – Usually in the reference range

Imaging studies

Imaging studies include MRI and ultrasonography. MRI is the most helpful study in the diagnosis of neonatal hemochromatosis 10.

Ultrasonography demonstrates patency of the ductus venosum; this is because of liver injury and, thus, portocaval shunting occurs.

MRI can be used to detect increased levels of iron in the liver compared with levels in normal tissues and can be used to document any areas of siderosis of the pancreas and myocardium. Absence of siderosis of the spleen may also be observed.

MRI of infants in utero has not demonstrated any siderosis or signs of neonatal hemochromatosis.

Biopsy

Liver biopsy is not easily performed in these infants because of the increased tendency of bleeding, but it is helpful in aiding in the diagnosis.

Another option is to perform a punch biopsy of the oral mucosa. This area is used because of the presence of the small salivary glands. Punch biopsy is performed by using 3-mm punch biopsy of the mucosa of the lower lip, and bleeding can be controlled. Salivary glands are siderotic if neonatal hemochromatosis is present.

Histologic findings

Microscopic examination of the liver reveals that the hepatocytes have giant-cell transformation or pseudoacinar transformation with bile plugs, or no hepatocytes are present at all. Also, the hepatocytes may show siderosis, while Kupffer cells are spared. Scarring may be present from macrophages, which contain high levels of stainable iron. The bile duct is proliferated. The spleen, lymph nodes, and bone marrow contain a small amount of stainable iron. The placenta is not siderotic, and villitis has not been reported.

Neonatal hemochromatosis treatment

The treatment of neonatal hemochromatosis is controversial. Recent evidence suggests that interfering with the alloimmune liver injury by treating affected babies with double-volume blood exchange transfusion and high-dose intravenous immunoglobulin can significantly improve survival. Other treatment options include liver transplantation. Therapy with a combination of certain drugs and antioxidants has proven ineffective. The results of these treatments have varied. Regardless of the treatment option, early diagnosis and prompt treatment are essential for achieving a positive outcome.

At present, liver transplantation is the only known curative treatment. Neonatal hemochromatosis is the most common cause of liver transplantation in newborns and the procedure has achieved long-term survival in some cases. Studies have shown that iron does not redeposit after transplantation. However, there are numerous risks involved with liver transplant (e.g., cancer risk due to immunosuppressant medications) and additional complications in infants with neonatal hemochromatosis (prematurity, small size for gestational age, potential damage to other organs).

In rare cases, some infants with neonatal hemochromatosis have improved without any treatment outside of standard supportive intensive care (spontaneous resolution). Therapy aimed at preventing neonatal hemochromatosis before it occurs has proven very effective. Researchers treated pregnant women (all of whom previously have had a child with neonatal hemochromatosis) with high-dose IVIG during pregnancy, with greater than 95% successful outcome. Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) therapy modifies the activity of the immune system (immunomodulation). IVIG is a solution containing antibodies donated from healthy individuals and administered directly to a vein. Any woman who has had a baby affected with NH should consider this therapy in subsequent pregnancies.

Maternal treatment

In a study by Whitington and Hibbard 11, 15 women whose most recent pregnancy ended in documented neonatal hemochromatosis were treated with intravenous immunoglobulin 1 g/kg/wk from 18 weeks’ gestation until end of gestation; 12 infants had evidence of neonatal hemochromatosis, but all survived with or without medical treatment and were healthy at the time of the report. However, this is a small study, and further trials are needed.

Neonatal hemochromatosis survival rate

Neonatal hemochromatosis prognosis is extremely poor. Some infants recover with supportive care, but this rarely occurs. At present, liver transplantation is the only known curative treatment. Survival rates in babies who undergo liver transplantation is reportedly 50% 8. Studies have shown that iron does not redeposit after transplantation. However, there are numerous risks involved with liver transplant (e.g., cancer risk due to immunosuppressant medications) and additional complications in infants with neonatal hemochromatosis (prematurity, small size for gestational age, potential damage to other organs).

In rare cases, some infants with neonatal hemochromatosis have improved without any treatment outside of standard supportive intensive care (spontaneous resolution). Therapy aimed at preventing neonatal hemochromatosis before it occurs has proven very effective. Researchers treated pregnant women (all of whom previously have had a child with neonatal hemochromatosis) with high-dose IVIG during pregnancy, with greater than 95% successful outcome. Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) therapy modifies the activity of the immune system (immunomodulation). IVIG is a solution containing antibodies donated from healthy individuals and administered directly to a vein. Any woman who has had a baby affected with NH should consider this therapy in subsequent pregnancies.

- Adams PC, Searle J. Neonatal hemochromatosis: a case and review of the literature. Am J Gastroenterol. 1988 Apr. 83(4):422-5.[↩]

- Muller-Berghaus J, Knisely AS, Zaum R, et al. Neonatal haemochromatosis: report of a patient with favourable outcome. Eur J Pediatr. 1997 Apr. 156(4):296-8.[↩]

- Whitington PF. Gestational alloimmune liver disease and neonatal hemochromatosis. Semin Liver Dis. 2012 Nov. 32(4):325-32.[↩]

- Neonatal hemochromatosis. https://rarediseases.info.nih.gov/diseases/7172/neonatal-hemochromatosis[↩]

- Neonatal Hemochromatosis. https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/neonatal-hemochromatosis[↩][↩][↩]

- Neonatal Hemochromatosis. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/929625-overview[↩]

- Colletti RB, Clemmons JJ. Familial neonatal hemochromatosis with survival. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1988 Jan-Feb. 7(1):39-45.[↩]

- Rodrigues F, Kallas M, Nash R, et al. Neonatal hemochromatosis–medical treatment vs. transplantation: the king’s experience. Liver Transpl. 2005 Nov. 11 (11):1417-24.[↩][↩]

- Machtei A, Klinger G, Shapiro R, Konen O, Sirota L. Clinical and Imaging Resolution of Neonatal Hemochromatosis following Treatment. Case Rep Crit Care. 2014. 2014:650916.[↩]

- Liet JM, Urtin-Hostein C, Joubert M, et al. Neonatal hemochromatosis [in French]. Arch Pediatr. 2000 Jan. 7(1):40-4.[↩]

- Whitington PF, Hibbard JU. High-dose immunoglobulin during pregnancy for recurrent neonatal haemochromatosis. Lancet. 2004 Nov 6-12. 364(9446):1690-8.[↩]