Nerve compression

Nerve compression occurs when too much pressure is applied to a nerve by surrounding tissues, such as bones, cartilage, muscles or tendons. This pressure disrupts the nerve’s function, causing pain, tingling, numbness or weakness.

Nerve compression can occur at a number of sites in your body. A herniated disk in your lower spine, for example, may put pressure on a nerve root, causing pain that radiates down the back of your leg. Likewise, a nerve compression in your wrist can lead to pain and numbness in your hand and fingers (carpal tunnel syndrome).

With rest and other conservative treatments, most people recover from a nerve compression within a few days or weeks. Sometimes, surgery is needed to relieve pain from a nerve compression.

Nerve compression causes

Nerve compression occurs when too much pressure (compression) is applied to a nerve by surrounding tissues.

In some cases, this tissue might be bone or cartilage, such as in the case of a herniated spinal disk that compresses a spinal nerve root. In other cases, muscle or tendons may cause the condition.

In the case of carpal tunnel syndrome, a variety of tissues may be responsible for compression of the carpal tunnel’s median nerve, including swollen tendon sheaths within the tunnel, enlarged bone that narrows the tunnel, or a thickened and degenerated ligament.

A number of conditions may cause tissue to compress a nerve or nerves, including:

- Injury

- Rheumatoid or wrist arthritis

- Stress from repetitive work

- Hobbies or sports activities

- Obesity

If nerve compression for only a short time, there’s usually no permanent damage. Once the pressure is relieved, nerve function returns to normal. However, if the pressure continues, chronic pain and permanent nerve damage can occur.

Risk factors for nerve compression

The following factors may increase your risk of experiencing a nerve compression:

- Sex. Women are more likely to develop carpal tunnel syndrome, possibly due to having smaller carpal tunnels.

- Bone spurs. Trauma or a condition that causes bone thickening, such as osteoarthritis, can cause bone spurs. Bone spurs can stiffen the spine as well as narrow the space where your nerves travel, pinching nerves.

- Rheumatoid arthritis. Inflammation caused by rheumatoid arthritis can compress nerves, especially in your joints.

- Thyroid disease. People with thyroid disease are at higher risk of carpal tunnel syndrome.

Other risk factors include:

- Diabetes. People with diabetes are at higher risk of nerve compression.

- Overuse. Jobs or hobbies that require repetitive hand, wrist or shoulder movements, such as assembly line work, increase your likelihood of a nerve compression.

- Obesity. Excess weight can add pressure to nerves.

- Pregnancy. Water and weight gain associated with pregnancy can swell nerve pathways, compressing your nerves.

- Prolonged bed rest. Long periods of lying down can increase the risk of nerve compression.

Nerve compression prevention

The following measures may help you prevent a nerve compression:

- Maintain good positioning — don’t cross your legs or lie in any one position for a long time.

- Incorporate strength and flexibility exercises into your regular exercise program.

- Limit repetitive activities and take frequent breaks when engaging in these activities.

- Maintain a healthy weight.

Nerve compression symptoms

Nerve compression signs and symptoms include:

- Numbness or decreased sensation in the area supplied by the nerve

- Sharp, aching or burning pain, which may radiate outward

- Tingling, pins and needles sensations (paresthesia)

- Muscle weakness in the affected area

- Frequent feeling that a foot or hand has “fallen asleep”

The problems related to a nerve compression may be worse when you’re sleeping.

See your doctor if the signs and symptoms of a nerve compression that last for several days and don’t respond to self-care measures, such as rest and over-the-counter pain relievers.

Nerve compression test

Your doctor will ask about your symptoms and conduct a physical examination.

If your doctor suspects a nerve compression, you may undergo some tests. These tests may include:

- Nerve conduction study. This test measures electrical nerve impulses and functioning in your muscles and nerves through electrodes placed on your skin. The study measures the electrical impulses in your nerve signals when a small current passes through the nerve. Test results tell your doctor whether you have a damaged nerve.

- Electromyography (EMG). During an EMG, your doctor inserts a needle electrode through your skin into various muscles. The test evaluates the electrical activity of your muscles when they contract and when they’re at rest. Test results tell your doctor if there is damage to the nerves leading to the muscle.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). This test uses a powerful magnetic field and radio waves to produce detailed views of your body in multiple planes. This test may be used if your doctor suspects you have nerve root compression.

- High-resolution ultrasound. Ultrasound uses high-frequency sound waves to produce images of structures within your body. It’s helpful for diagnosing nerve compression syndromes, such as carpal tunnel syndrome.

Nerve compression treatment

The most frequently recommended treatment for nerve compression is rest for the affected area. Your doctor will ask you to stop any activities that cause or aggravate the nerve compression.

Depending on the location of the nerve compression, you may need a splint or brace to immobilize the area. If you have carpal tunnel syndrome, your doctor may recommend wearing a splint during the day as well as at night because wrists flex and extend frequently during sleep.

Physical therapy

A physical therapist can teach you exercises that strengthen and stretch the muscles in the affected area to relieve pressure on the nerve. He or she may also recommend modifications to activities that aggravate the nerve.

Medications

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin IB, others) or naproxen sodium (Aleve), can help relieve pain.

Corticosteroid injections, given by mouth or by injection, may help minimize pain and inflammation.

Surgery

If the nerve compression doesn’t improve after several weeks to a few months with conservative treatments, your doctor may recommend surgery to take pressure off the nerve. The type of surgery varies depending on the location of the nerve compression.

Surgery may entail removing bone spurs or a part of a herniated disk in the spine, for example, or severing the carpal ligament to allow more room for the nerve to pass through the wrist.

Ulnar nerve compression

Ulnar nerve compression also called ulnar nerve entrapment or cubital tunnel syndrome, occurs when the ulnar nerve in the arm becomes compressed or irritated 1. Ulnar nerve compression at the elbow is the second most common compressive neuropathy of the upper extremity following median nerve compression (carpal tunnel syndrome) 2. A study of 91 patients identified that close to 60% of these patients had anatomical changes in the cubital tunnel that caused the ulnar nerve neuropathy, of which nearly 20% of patients had a subluxation of the ulnar nerve. Other causes identified in this study were osteophytes in almost 7% of patients and luxation of the ulnar nerve in nearly 10% of patients. Post-traumatic lesions also can cause symptoms in about 3.3% of patients 3. The prevalence of ulnar nerve compression is not known precisely, but is estimated at 1% in the United States 4. Although it is reasonable to try the conservative option such as elbow extension splinting, keeping the elbow in the extended posture is functionally limiting and is not tolerated by most working patients. On the other hand, although surgical treatment is the preferred option for incapacitating discomfort, the most appropriate surgical treatment has not been sufficiently researched. The controversy about surgery for ulnar nerve compression has persisted for decades, and the choice of the procedure is often based on personal preferences rather than evidence.

The ulnar nerve is one of the three main nerves in your arm. It travels from your neck down into your hand, and can be constricted in several places along the way, such as beneath the collarbone or at the wrist. The most common place for compression of the nerve is behind the inside part of the elbow. Ulnar nerve compression at the elbow is called “cubital tunnel syndrome” 5.

At the elbow, the ulnar nerve travels through a tunnel of tissue (the cubital tunnel) that runs under a bump of bone at the inside of your elbow. This bony bump is called the medial epicondyle. The spot where the nerve runs under the medial epicondyle is commonly referred to as the “funny bone.” At the funny bone the nerve is close to your skin, and bumping it causes a shock-like feeling.

Numbness and tingling in the hand and fingers are common symptoms of ulnar nerve compression. In most cases, symptoms can be managed with conservative treatments like changes in activities and bracing. If conservative methods do not improve your symptoms, or if the nerve compression is causing muscle weakness or damage in your hand, your doctor may recommend surgery.

Ulnar nerve anatomy

At the elbow, the ulnar nerve travels through a tunnel of tissue (the cubital tunnel) that runs under a bump of bone at the inside of your elbow. This bony bump is called the medial epicondyle. The spot where the nerve runs under the medial epicondyle is commonly referred to as the “funny bone.” At the funny bone the nerve is close to your skin, and bumping it causes a shock-like feeling.

Beyond the elbow, the ulnar nerve travels under muscles on the inside of your forearm and into your hand on the side of the palm with the little finger. As the nerve enters the hand, it travels through another tunnel (Guyon’s canal).

The ulnar nerve gives feeling to the little finger and half of the ring finger. It also controls most of the little muscles in the hand that help with fine movements, and some of the bigger muscles in the forearm that help you make a strong grip.

Figure 1. Ulnar nerve

Figure 2. The ulnar nerve runs behind the medial epicondyle of the humerus on the inside of the elbow.

Figure 3. The ulnar nerve gives sensation (feeling) to the little finger and to half of the ring finger on both the palm and back side of the hand.

Ulnar nerve compression causes

In many cases of ulnar nerve compression, the exact cause is not known. The ulnar nerve is especially vulnerable to compression at the elbow because it must travel through a narrow space with very little soft tissue to protect it.

Common causes of ulnar nerve compression

There are several things that can cause pressure on the ulnar nerve at the elbow:

- When your bend your elbow, the ulnar nerve must stretch around the boney ridge of the medial epicondyle. Because this stretching can irritate the nerve, keeping your elbow bent for long periods or repeatedly bending your elbow can cause painful symptoms. For example, many people sleep with their elbows bent. This can aggravate symptoms of ulnar nerve compression and cause you to wake up at night with your fingers asleep.

- In some people, the nerve slides out from behind the medial epicondyle when the elbow is bent. Over time, this sliding back and forth may irritate the nerve.

- Leaning on your elbow for long periods of time can put pressure on the nerve.

- Fluid buildup in the elbow can cause swelling that may compress the nerve.

- A direct blow to the inside of the elbow can cause pain, electric shock sensation, and numbness in the little and ring fingers. This is commonly called “hitting your funny bone.”

Risk factors for ulnar nerve compression

Some factors put you more at risk for developing ulnar nerve compression (cubital tunnel syndrome). These include:

- Prior fracture or dislocations of the elbow

- Bone spurs/ arthritis of the elbow

- Swelling of the elbow joint

- Cysts near the elbow joint

- Repetitive or prolonged activities that require the elbow to be bent or flexed

Ulnar nerve compression symptoms

Ulnar nerve compression can cause an aching pain on the inside of the elbow. Most of the symptoms, however, occur in your hand.

- Numbness and tingling in the ring finger and little finger are common symptoms of ulnar nerve entrapment. Often, these symptoms come and go. They happen more often when the elbow is bent, such as when driving or holding the phone. Some people wake up at night because their fingers are numb.

- The feeling of “falling asleep” in the ring finger and little finger, especially when your elbow is bent. In some cases, it may be harder to move your fingers in and out, or to manipulate objects.

- Weakening of the grip and difficulty with finger coordination (such as typing or playing an instrument) may occur. These symptoms are usually seen in more severe cases of nerve compression.

- If the nerve is very compressed or has been compressed for a long time, muscle wasting in the hand can occur. Once this happens, muscle wasting cannot be reversed. For this reason, it is important to see your doctor if symptoms are severe or if they are less severe but have been present for more than 6 weeks.

Ulnar nerve compression diagnosis

Your doctor will discuss your medical history and general health. He or she may also ask about your work, your activities, and what medications you are taking.

After discussing your symptoms and medical history, your doctor will examine your arm and hand to determine which nerve is compressed and where it is compressed. Some of the physical examination tests your doctor may do include:

- Tap over the nerve at the funny bone. If the nerve is irritated, this can cause a shock into the little finger and ring finger — although this can happen when the nerve is normal as well.

- Check whether the ulnar nerve slides out of normal position when you bend your elbow.

- Move your neck, shoulder, elbow, and wrist to see if different positions cause symptoms.

- Check for feeling and strength in your hand and fingers.

Ulnar nerve compression test

X-rays. These imaging tests provide detailed pictures of dense structures, like bone. Most causes of compression of the ulnar nerve cannot be seen on an x-ray. However, your doctor may take x-rays of your elbow or wrist to look for bone spurs, arthritis, or other places that the bone may be compressing the nerve.

Nerve conduction studies. These tests can determine how well the nerve is working and help identify where it is being compressed.

Nerves are like “electrical cables” that travel through your body carrying messages between your brain and muscles. When a nerve is not working well, it takes too long for it to conduct.

During a nerve conduction test, the nerve is stimulated in one place and the time it takes for there to be a response is measured. Several places along the nerve will be tested and the area where the response takes too long is likely to be the place where the nerve is compressed.

Nerve conduction studies can also determine whether the compression is also causing muscle damage. During the test, small needles are put into some of the muscles that the ulnar nerve controls. Muscle damage is a sign of more severe nerve compression.

Ulnar nerve compression treatment

Unless your nerve compression has caused a lot of muscle wasting, your doctor will most likely first recommend nonsurgical treatment.

Nonsurgical Treatment

- Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory (NSAIDs) medicines. If your symptoms have just started, your doctor may recommend an anti-inflammatory medicine, such as ibuprofen, to help reduce swelling around the nerve.

Although steroids, such as cortisone, are very effective anti-inflammatory medicines, steroid injections are generally not used because there is a risk of damage to the nerve.

- Bracing or splinting. Your doctor may prescribe a padded brace or split to wear at night to keep your elbow in a straight position.

- Nerve gliding exercises. Some doctors think that exercises to help the ulnar nerve slide through the cubital tunnel at the elbow and the Guyon’s canal at the wrist can improve symptoms. These exercises may also help prevent stiffness in the arm and wrist.

Home remedies

There are many things you can do at home to help relieve symptoms. If your symptoms interfere with normal activities or last more than a few weeks, be sure to schedule an appointment with your doctor.

- Avoid activities that require you to keep your arm bent for long periods of time.

- If you use a computer frequently, make sure that your chair is not too low. Do not rest your elbow on the armrest.

- Avoid leaning on your elbow or putting pressure on the inside of your arm. For example, do not drive with your arm resting on the open window.

- Keep your elbow straight at night when you are sleeping. This can be done by wrapping a towel around your straight elbow or wearing an elbow pad backwards.

Surgical Treatment

Your doctor may recommend surgery to take pressure off of the nerve if:

- Nonsurgical methods have not improved your condition

- The ulnar nerve is very compressed

- Nerve compression has caused muscle weakness or damage

There are a few surgical procedures that will relieve pressure on the ulnar nerve at the elbow. Your orthopaedic surgeon will talk with you about the option that would be best for you.

These procedures are most often done on an outpatient basis, but some patients do best with an overnight stay at the hospital.

Cubital tunnel release. In this operation, the ligament “roof” of the cubital tunnel is cut and divided. This increases the size of the tunnel and decreases pressure on the nerve.

After the procedure, the ligament begins to heal and new tissue grows across the division. The new growth heals the ligament, and allows more space for the ulnar nerve to slide through.

Cubital tunnel release tends to work best when the nerve compression is mild or moderate and the nerve does not slide out from behind the bony ridge of the medial epicondyle when the elbow is bent.

Ulnar nerve anterior transposition. In many cases, the nerve is moved from its place behind the medial epicondyle to a new place in front of it. Moving the nerve to the front of the medial epicondyle prevents it from getting caught on the bony ridge and stretching when you bend your elbow. This procedure is called an anterior transposition of the ulnar nerve.

The nerve can be moved to lie under the skin and fat but on top of the muscle (subcutaneous transposition), or within the muscle (intermuscular transposition), or under the muscle (submuscular transposition).

Medial epicondylectomy. Another option to release the nerve is to remove part of the medial epicondyle. Like ulnar nerve transposition, this technique also prevents the nerve from getting caught on the boney ridge and stretching when your elbow is bent.

Surgical Recovery

Depending on the type of surgery you have, you may need to wear a splint for a few weeks after the operation. A submuscular transposition usually requires a longer time (3 to 6 weeks) in a splint.

Your surgeon may recommend physical therapy exercises to help you regain strength and motion in your arm. He or she will also talk with you about when it will be safe to return to all your normal activities.

Surgical Outcome

The results of surgery are generally good. Each method of surgery has a similar success rate for routine cases of nerve compression. If the nerve is very badly compressed or if there is muscle wasting, the nerve may not be able to return to normal and some symptoms may remain even after the surgery. Nerves recover slowly, and it may take a long time to know how well the nerve will do after surgery.

Nerve gliding exercises. Some doctors think that exercises to help the ulnar nerve slide through the cubital tunnel at the elbow and the Guyon’s canal at the wrist can improve symptoms. These exercises may also help prevent stiffness in the arm and wrist.

Radial nerve compression

Radial nerve compression or radial nerve entrapment is an uncommon diagnosis that is prone to under-recognition. Radial nerve compression can occur at any location within the course of the radial nerve distribution, but the most frequent location of entrapment occurs in the proximal forearm. This most common location is typically in proximity to the supinator and often will involve the posterior interosseous nerve branch. The annual incidence rate of the posterior interosseous nerve compression is estimated to be 0.03% while the rate for superficial radial nerve compression is 0.003% 6.

The radial nerve arises from C5 to C8 and provides a motor function to the extensors of the forearm, wrist, fingers, and thumb (see Figures 4 to 8). The superficial radial nerve provides a sensory function to the posterior forearm. Depending on the location of radial nerve compression a patient may experience pain, numbness, weakness, and overall dysfunction or any combination of these 7.

Radial nerve anatomy

The radial nerve arises from ventral rami of C5 to C8 (+/- T1) and is a continuation of the posterior cord of the brachial plexus and is the largest branch of the brachial plexus, innervating almost the entire posterior side of the upper limb and provides a motor function to the extensor muscles of the forearm, wrist, fingers, and thumb.

Within the axilla, the radial nerve has three branches: sensory posterior cutaneous nerve of the arm and motor branch to the long and medial head of the triceps 8. The radial nerve passes anterior to the subscapularis, latissimus dorsi and teres major. This is the first possible site of compression. An anomalous muscle, the accessory subscapularis-teres-latissimus is reported in literature to be another cause of compression of the radial nerve at this level 9. Another potential cause of compression, as described by Spinner 10 is penetration of the nerve directly by the subscapular artery more distally in the axilla, forming a neural loop.

The radial nerve enters the posterior compartment of the arm by traveling through the triangular interval bounded by the teres major superiorly, the long head of the triceps medially and the lateral head of the triceps laterally. The radial nerve then exits the axilla, courses through the lateral head of triceps brachii and winds around the posterior humerus in the radial groove accompanied by the profunda brachii artery, sending branches to the triceps brachii. Lorem et al. 11 described this as another possible site of entrapment. Familial radial nerve entrapment syndrome 12 also occurs secondary to compression at the lateral head of the triceps. Intermittent compression of the nerve may also occur secondary to genetic defect in Schwann cell myelin metabolism 13. The radial nerve gives off the following branches in the upper arm – the inferior lateral cutaneous nerve of the arm, posterior cutaneous nerve of the forearm and motor branches to the lateral head of triceps and anconeus. The radial nerve is in close proximity to the humerus in the spiral groove and is easily identified on ultrasound in its short axis overlying the humerus between the lateral and medial heads of the triceps. The radial nerve then courses from the posterior to anterior compartment of the arm by piercing the lateral intermuscular septum which is another possible site of entrapment.

The radial nerve then curves anteriorly around the lateral epicondyle at the elbow, where it divides into a superficial and a deep branches (posterior interosseous nerve) under the margin of the brachioradialis muscle in the lateral border of the cubital fossa.

The deep branch (posterior interosseous nerve) is predominantly motor and passes between the two heads of the supinator muscle to access and supply muscles in the extensor muscles on the forearm. The deep branch (posterior interosseous nerve) winds around the radial head, lying between two heads of the supinator muscle and then travels on the dorsal surface of the interosseous membrane. The superficial layer of the supinator muscle forms the arcade of Frohse which is the most common site of entrapment neuropathy causing the radial tunnel syndrome 14. Two anomalous courses of the posterior interosseous nerve have been reported in the literature by Woltman and Learmonth. First is passage of the nerve within the substance of the supinator, and the other involves a branch travelling superficial to the supinator brevis 15. The origin of the radial tunnel is where the deep branch (lateral) courses over the radio-humeral joint. The tunnel ends at the distal edge of the superficial supinator where the posterior interosseous nerve is formed. Radial tunnel syndrome can be caused by the arcade of Frohse, fibrous fascial bands coursing superficial to the nerve or the vascular leash of Henry 16 which is formed by the recurrent radial vessels. The posterior interosseous nerve supplies the abductor pollicis longus, the extensor pollicis brevis, the extensor indicis proprius and the extensor pollicis longus.

The superficial branch of the radial nerve is sensory. The superficial radial nerve descends medially along the lateral edge of the radius under cover of the brachioradialis muscle and in association with the radial artery. Approximately two-thirds of the way down the forearm, the superficial branch of the radial nerve passes laterally and posteriorly around the radial side of the forearm deep to the tendon of the brachioradialis . The superficial radial nerve continues into the hand where it pierces the lateral fascia to enter the anatomical snuffbox and gives sensory innervation to the dorsal surface of three and a half digits on the radial aspect. It also innervates the extensor digitorum, the extensor digiti minimi and the extensor carpi ulnaris muscles.

Figure 4. Radial nerve

Figure 5. Radial nerve in the arm and posterior shoulder

Figure 6. Radial nerve in the forearm

Figure 7. Radial nerve distribution

Radial nerve compression causes

Radial nerve compression is often thought to be a result of overuse but can certainly occur secondary to other causes such as direct trauma, fractures, lacerations, compressive devices, or post-surgical changes. The radial nerve divides into the superficial radial and posterior interosseous nerves at the level of the radiocapitellar joint. The posterior interosseous nerve runs along the radial neck before piercing the supinator muscle, a common site of entrapment. The nerve further divides into four terminal branches that can typically be compressed at one of four other sites as well. These four sites are the fibrous bands around the radial head, the recurrent radial vessels, the arcade of Frohse, and/or the tendinous margin of the extensor carpi radialis brevis. Overuse actions and exercises that can lead to this condition are often repetitive pronation and supination of the wrist and forearm and commonly occur in the locations 17.

Radial nerve compression symptoms

Radial nerve compression symptoms can certainly vary given multiple areas of possible compression. Symptoms are usually very slow developing. The duration of symptoms often averages multiple years before a definitive diagnosis is made. As mentioned previously, symptoms of radial nerve compression are pain, sensory and motor changes, paresthesias, and/or paralysis. Physical exam and/or history often reveal symptoms limited to the dorsoradial aspect of the distal forearm and hand. Findings of decreased sensation over the dorsoradial aspect of the forearm or hand are helpful in establishing the diagnosis. A positive Tinel sign along the radial aspect of the mid forearm is suggestive of this process. Wrist flexion, ulnar deviation, and pronation place strain on the nerve and will often reproduce or exacerbate symptoms. Resisted extension of the middle finger with the elbow extended is another sign of radial nerve compression. This sign is often used to aid in the diagnosis of lateral epicondylitis but it also often positive in cases of radial nerve compression.

Radial nerve compression diagnosis

- If radial nerve compression is suspected, radiography should be performed to detect or rule out a fracture, healing callus, or tumor as the cause of radial nerve compression.

- Ultrasonography can often provide reliable visualization of injured nerves. Axonal swelling, hypoechogenicity of the nerve, loss of continuity of a nerve bundle, formation of a neuroma, and/or partial laceration of a nerve can all be visualized which may aid in diagnosis.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be useful in detecting more subtle causes not found on radiographs or ultrasound such as small tumors, masses, aneurysms, or a compressive synovitis. MRI can also at times detect nerve changes during acute compressions.

- A diagnostic nerve block to help define the distribution of pathology and presentation is considered in some situations.

- EMG/Nerve conduction studies can also be considered but are inconsistent and should only be considered if surgery is a possibility.

- No standard laboratory work is necessary for establishing the diagnosis 18.

Radial nerve compression treatment

Radial tunnel syndrome exercises

Radial tunnel syndrome is a painful condition caused by pressure on the radial nerve — one of the three main nerves in your arm. The most common place for compression of the radial nerve is at the elbow where the nerve enters a tight tunnel made by muscle, bone, and tendon.

Specific exercises to help the radial nerve slide through the tunnel at the elbow can help improve symptoms. Stretching and strengthening the muscles of the forearm can also help to relieve pain and tenderness. Following a well-structured exercise program will help you return to daily activities, as well as sports and other recreational pastimes.

Wrist extension stretch

Step-by-step directions

- Straighten your arm and bend your wrist back as if signaling someone to “stop.”

- Use your opposite hand to apply gentle pressure across the palm and pull it toward you until you feel a stretch on the inside of your forearm.

- Hold the stretch for 15 seconds.

- Repeat 5 times, then perform this stretch on the other arm.

This stretch should be done throughout the day, especially before activity. After recovery, this stretch should be included as part of a warm-up to activities that involve gripping, such as gardening, tennis, and golf.

Figure 9. Wrist extension stretch

Wrist flexion stretch

Step-by-step directions

- Straighten your arm with your palm facing down and bend your wrist so that your fingers point down.

- Gently pull your hand toward your body until you feel a stretch on the outside of your forearm.

- Hold the stretch for 15 seconds.

- Repeat 5 times, then perform this stretch on the other arm.

This stretch should be done throughout the day, especially before activity. After recovery, this stretch should be included as part of a warm-up to activities that involve gripping, such as gardening, tennis, and golf.

Figure 10. Wrist flexion stretch

Wrist supination stretch

Step-by-step directions

- Bend your elbow at the side of your body with your palm facing the ceiling.

- Use your opposite hand to hold at your wrist and gently turn your forearm further into the palm-up position until you feel a stretch. Be sure to hold at your wrist – not your hand – to turn your forearm.

- Hold the stretch for 15 seconds.

- Repeat 5 times, then perform this stretch on the other arm

This stretch will help with activities that require a “palm up” position, gripping an object, and/or twisting (such as when using a screwdriver).

Figure 11. Wrist supination stretch

Radial Nerve Glides

Radial Nerve GlidesStep-by-step directions

- Stand comfortably with your arms loose at your sides.

- Drop your shoulder down and reach your fingers toward the floor.

- Internally rotate your arm (thumb toward your body) and flex your wrist with the palm up.

- Gently tilt your head away from the side you are stretching.

- Raise your arm up and away from your body as you continue to flex your wrist and tilt your head.

- Hold each position of the glide for 3 to 5 seconds

Nerve glides help to restore nerve motion. This exercise will help the radial nerve glide normally through structures that are putting pressure on the nerve.

Figure 12. Radial nerve glides

First and Second Degree Nerve Injuries

- Most patients respond and recover after several months — recommended management consists of serial exams and serial EMG/nerve conduction study testing

- Most patients respond well to conservative therapy. Consider removing any restrictive or compressive devices that are routinely worn. Consider relative rest from offending activity such as limiting repetitive pronation, supination, wrist flexion, and ulnar deviation. Often nerve glide exercises as part of occupation/physical therapy are performed in conjunction with rest and activity modification. If symptoms do not resolve with cessation of activity and rest, then consider splinting.

- If an area of pathology indicates possible compression and can be visualized on ultrasound, providers can consider ultrasound guided hydrodissection to free the compressed portion of the nerve.

- Oral or topical NSAIDs can be used for pain. Steroid and an anesthetic combination can be injected into the point of maximal tenderness for symptomatic relief. The steroid may help decrease any inflammation contributing to the process.

- In the setting of suspected mild degrees of nerve injury, but either prolonged, absent, or delayed evidence of recovery of nerve function both clinically and by serial EMG/nerve conduction study testing, surgery should be the last option if this process has become chronic and conservative treatment has failed after six to 12 months 19.

Third Degree Nerve Injuries (Neurotmesis)

- Acutely, direct surgical repair of the partial versus complete nerve laceration

- Nerve grafting techniques are employed in the setting of lacerations with retractions; often this can present in the subacute setting after injury

- Residual defects or “injury gap” measuring >2.5cm are recommended for nerve grafting techniques

- Autograft options include the sural or saphenous nerves

- There is no documented improved functional recovery or outcome when comparing autograft versus allograft or nerve conduits

- Autograft options include the sural or saphenous nerves

Radial nerve compression prognosis

The prognosis after radial nerve compression depend on the severity of the injury. For those with neuropraxic injury, the outcome is good in most cases. For those with axonotmesis, recovery depends on the completeness of release. Unfortunately, many patients have residual deficits. Following neurotmesis, recovery is usually limited even with surgical repair. All patients need extended physical and occupational therapy, and recovery can take months or even years 20.

Median nerve compression

Median nerve compression at the wrist is called carpal tunnel syndrome, which is a common condition that causes pain, numbness, tingling and other symptoms in your hand and arm. Carpal tunnel syndrome is caused by a compressed median nerve in the carpal tunnel, a narrow passageway on the palm side of your wrist.

The anatomy of your wrist, health problems and possibly repetitive hand motions can contribute to carpal tunnel syndrome.

In most patients, carpal tunnel syndrome gets worse over time, so early diagnosis and treatment are important. Early on, symptoms can often be relieved with simple measures like wearing a wrist splint or avoiding certain activities.

If pressure on the median nerve continues, however, it can lead to nerve damage and worsening symptoms. To prevent permanent damage, surgery to take pressure off the median nerve may be recommended for some patients.

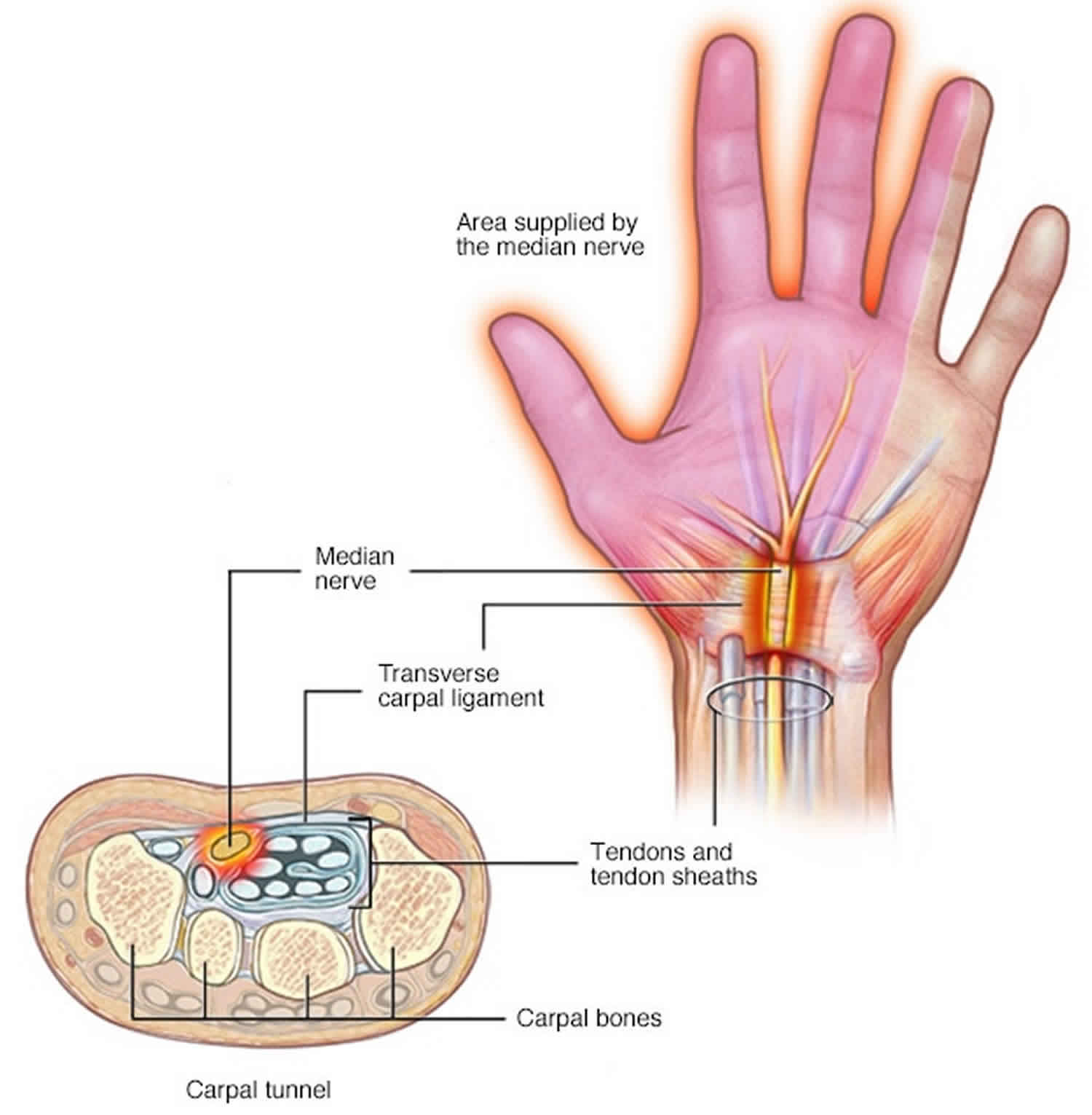

Carpal tunnel anatomy

The carpal tunnel is a narrow passageway in the wrist, about an inch wide. The floor and sides of the tunnel are formed by small wrist bones called carpal bones.

The roof of the tunnel is a strong band of connective tissue called the transverse carpal ligament. Because these boundaries are very rigid, the carpal tunnel has little capacity to “stretch” or increase in size.

The median nerve is one of the main nerves in the hand. It originates as a group of nerve roots in the neck. These roots come together to form a single nerve in the arm. The median nerve goes down the arm and forearm, passes through the carpal tunnel at the wrist, and goes into the hand. The nerve provides feeling in the thumb and index, middle, and ring fingers. The nerve also controls the muscles around the base of the thumb.

The nine tendons that bend the fingers and thumb also travel through the carpal tunnel. These tendons are called flexor tendons.

Figure 13. Median nerve compression

Median nerve compression causes

Carpal tunnel syndrome is caused by pressure on the median nerve. The median nerve runs from your forearm through a passageway in your wrist (carpal tunnel) to your hand. It provides sensation to the palm side of your thumb and fingers, except the little finger. It also provides nerve signals to move the muscles around the base of your thumb (motor function). Anything that squeezes or irritates the median nerve in the carpal tunnel space may lead to carpal tunnel syndrome. A wrist fracture can narrow the carpal tunnel and irritate the nerve, as can the swelling and inflammation resulting from rheumatoid arthritis.

Carpal tunnel syndrome occurs when the tunnel becomes narrowed or when tissues surrounding the flexor tendons swell, putting pressure on the median nerve. These tissues are called the synovium. Normally, the synovium lubricates the tendons, making it easier to move your fingers.

When the synovium swells, it takes up space in the carpal tunnel and, over time, crowds the nerve. This abnormal pressure on the nerve can result in pain, numbness, tingling, and weakness in the hand.

Most cases of carpal tunnel syndrome are caused by a combination of factors. Studies show that women and older people are more likely to develop the condition.

Risk factors for carpal tunnel syndrome

A number of factors have been associated with carpal tunnel syndrome. Although they may not directly cause carpal tunnel syndrome, they may increase your chances of developing or aggravating median nerve damage. These include:

- Heredity. This is likely an important factor. The carpal tunnel may be smaller in some people or there may be anatomic differences that change the amount of space for the nerve—and these traits can run in families.

- Anatomic factors. A wrist fracture or dislocation, or arthritis that deforms the small bones in the wrist, can alter the space within the carpal tunnel and put pressure on the median nerve. People with smaller carpal tunnels may be more likely to have carpal tunnel syndrome.

- Sex. Carpal tunnel syndrome is generally more common in women. This may be because the carpal tunnel area is relatively smaller in women than in men. Women who have carpal tunnel syndrome may also have smaller carpal tunnels than women who don’t have the condition.

- Nerve-damaging conditions. Some chronic illnesses, such as diabetes, increase your risk of nerve damage, including damage to your median nerve.

- Inflammatory conditions. Illnesses that are characterized by inflammation, such as rheumatoid arthritis, can affect the lining around the tendons in your wrist and put pressure on your median nerve.

- Obesity. Being obese is a significant risk factor for carpal tunnel syndrome.

- Alterations in the balance of body fluids. Fluid retention may increase the pressure within your carpal tunnel, irritating the median nerve. This is common during pregnancy and menopause. Carpal tunnel syndrome associated with pregnancy generally resolves on its own after pregnancy.

- Other medical conditions. Certain conditions, such as menopause, obesity, thyroid disorders, diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis and kidney failure, may increase your chances of carpal tunnel syndrome.

- Workplace factors. It’s possible that working with vibrating tools or on an assembly line that requires prolonged or repetitive flexing of the wrist may create harmful pressure on the median nerve or worsen existing nerve damage.

- Repetitive hand use. Repeating the same hand and wrist motions or activities over a prolonged period of time may aggravate the tendons in the wrist, causing swelling that puts pressure on the nerve.

- Hand and wrist position. Doing activities that involve extreme flexion or extension of the hand and wrist for a prolonged period of time can increase pressure on the nerve.

- Pregnancy. Hormonal changes during pregnancy can cause swelling.

However, the scientific evidence is conflicting and these factors haven’t been established as direct causes of carpal tunnel syndrome.

Several studies have evaluated whether there is an association between computer use and carpal tunnel syndrome. However, there has not been enough quality and consistent evidence to support extensive computer use as a risk factor for carpal tunnel syndrome, although it may cause a different form of hand pain.

Median nerve compression symptoms

Carpal tunnel syndrome symptoms usually start gradually. The first symptoms often include numbness or tingling in your thumb, index and middle fingers that comes and goes.

Carpal tunnel syndrome may also cause discomfort in your wrist and the palm of your hand. Common carpal tunnel syndrome symptoms include:

- Tingling or numbness. You may experience tingling and numbness in your fingers or hand. Usually the thumb and index, middle or ring fingers are affected, but not your little finger. Sometimes there is a sensation like an electric shock in these fingers. The sensation may travel from your wrist up your arm. These symptoms often occur while holding a steering wheel, phone or newspaper. The sensation may wake you from sleep. Many people “shake out” their hands to try to relieve their symptoms. The numb feeling may become constant over time.

- Occasional shock-like sensations that radiate to the thumb and index, middle, and ring fingers

- Pain or tingling that may travel up the forearm toward the shoulder

- Dropping things—due to weakness, numbness, or a loss of proprioception (awareness of where your hand is in space)

- Weakness and clumsiness in the hand. You may experience weakness in your hand and a tendency to drop objects. This may be due to the numbness in your hand or weakness of the thumb’s pinching muscles, which are also controlled by the median nerve.

In most cases, the symptoms of carpal tunnel syndrome begin gradually—without a specific injury. Many patients find that their symptoms come and go at first. However, as the condition worsens, symptoms may occur more frequently or may persist for longer periods of time.

Night-time symptoms are very common. Because many people sleep with their wrists bent, symptoms may awaken you from sleep. During the day, symptoms often occur when holding something for a prolonged period of time with the wrist bent forward or backward, such as when using a phone, driving, or reading a book.

Many patients find that moving or shaking their hands helps relieve their symptoms.

Median nerve compression diagnosis

Your doctor may ask you questions and conduct one or more of the following tests to determine whether you have carpal tunnel syndrome:

- History of symptoms. Your doctor will review the pattern of your symptoms. For example, because the median nerve doesn’t provide sensation to your little finger, symptoms in that finger may indicate a problem other than carpal tunnel syndrome. Carpal tunnel syndrome symptoms usually occur include while holding a phone or a newspaper, gripping a steering wheel, or waking up during the night.

- Physical examination. Your doctor will conduct a physical examination. He or she will test the feeling in your fingers and the strength of the muscles in your hand. Bending the wrist, tapping on the nerve or simply pressing on the nerve can trigger symptoms in many people.

- X-ray. Some doctors recommend an X-ray of the affected wrist to exclude other causes of wrist pain, such as arthritis ligament injury, or a fracture.

- Electromyogram (EMG). This test measures the tiny electrical discharges produced in muscles. During this test, your doctor inserts a thin-needle electrode into specific muscles to evaluate the electrical activity when muscles contract and rest. This test can identify muscle damage and also may rule out other conditions.

- Nerve conduction study. In a variation of electromyography, two electrodes are taped to your skin. A small shock is passed through the median nerve to see if electrical impulses are slowed in the carpal tunnel. This test may be used to diagnose your condition and rule out other conditions.

- Ultrasound. An ultrasound uses high-frequency sound waves to help create pictures of bone and tissue. Your doctor may recommend an ultrasound of your wrist to evaluate the median nerve for signs of compression.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans. These studies provide better images of the body’s soft tissues. Your doctor may order an MRI to help determine other causes for your symptoms or to look for abnormal tissues that could be impacting the median nerve. An MRI can also help your doctor determine if there are problems with the nerve itself—such as scarring from an injury or tumor.

Median nerve compression treatment

Although carpal tunnel syndrome is a gradual process, for most people carpal tunnel syndrome will worsen over time without some form of treatment. For this reason, it is important to be evaluated and diagnosed by your doctor early on. In the early stages, it may be possible to slow or stop the progression of the disease.

Nonsurgical Treatment

If diagnosed and treated early, the symptoms of carpal tunnel syndrome can often be relieved without surgery. If your diagnosis is uncertain or if your symptoms are mild, your doctor will recommend nonsurgical treatment first.

Nonsurgical treatments may include:

- Bracing or splinting. Wearing a brace or splint at night will keep you from bending your wrist while you sleep. Keeping your wrist in a straight or neutral position reduces pressure on the nerve in the carpal tunnel. It may also help to wear a splint during the day when doing activities that aggravate your symptoms.

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Medications such as ibuprofen and naproxen can help relieve pain and inflammation.

- Activity changes. Symptoms often occur when your hand and wrist are in the same position for too long—particularly when your wrist is flexed or extended. If your job or recreational activities aggravate your symptoms, changing or modifying these activities can help slow or stop progression of the disease. In some cases, this may involve making changes to your work site or work station.

- Nerve gliding exercises. Some patients may benefit from exercises that help the median nerve move more freely within the confines of the carpal tunnel. Specific exercises may be recommended by your doctor or therapist.

- Steroid injections. Corticosteroid, or cortisone, is a powerful anti-inflammatory agent that can be injected into the carpal tunnel. Although these injections often relieve painful symptoms or help to calm a flare up of symptoms, their effect is sometimes only temporary. A cortisone injection may also be used by your doctor to help diagnose your carpal tunnel syndrome.

Splinting and other conservative treatments are more likely to help if you’ve had only mild to moderate symptoms for less than 10 months.

If carpal tunnel syndrome is caused by rheumatoid arthritis or another inflammatory arthritis, then treating the arthritis may reduce symptoms of carpal tunnel syndrome. However, this is unproved.

Carpal tunnel syndrome exercises

Wrist extension stretch

Step-by-step directions (see Figure 9 above)

- Straighten your arm and bend your wrist back as if signaling someone to “stop.”

- Use your opposite hand to apply gentle pressure across the palm and pull it toward you until you feel a stretch on the inside of your forearm.

- Hold the stretch for 15 seconds.

- Repeat 5 times, then perform this stretch on the other arm.

This stretch should be done throughout the day, especially before activity. After recovery, this stretch should be included as part of a warm-up to activities that involve gripping, such as gardening, tennis, and golf.

Wrist flexion stretch

Step-by-step directions (see Figure 10 above)

- Straighten your arm with your palm facing down and bend your wrist so that your fingers point down.

- Gently pull your hand toward your body until you feel a stretch on the outside of your forearm.

- Hold the stretch for 15 seconds.

- Repeat 5 times, then perform this stretch on the other arm.

This stretch should be done throughout the day, especially before activity. After recovery, this stretch should be included as part of a warm-up to activities that involve gripping, such as gardening, tennis, and golf.

Medial Nerve Glides

Step-by-step directions

- Make a fist with your thumb outside your fingers (1)

- Extend your fingers while keeping your thumb close to the side of your hand (2)

- Keep your fingers straight and extend your wrist (bend your hand backward toward your forearm) (3)

- Keep your fingers and wrist in position and extend your thumb (4)

- Keep your fingers, wrist, and thumb extended and turn your forearm palm up (5)

- Keep your fingers, wrist, and thumb extended and use your other hand to gently stretch the thumb (6). Do not put too much pressure on your thumb in position 6.

Apply heat to your hand for 15 minutes before performing these exercises. After completing the exercises, apply a bag of crushed ice or frozen peas to your hand for 20 min-utes to prevent inflammation. Hold each position below for 3 to 7 seconds.

Figure 14. Medial Nerve Glides

Carpal tunnel tendon glides

Carpal tunnel tendon glidesApply heat to your hand for 15 minutes before performing these exercises. After completing the exercises, apply a bag of crushed ice or frozen peas to your hand for 20 minutes to prevent inflammation. Two series of tendon gliding exercises are provided here.

Follow these general instructions for both series:

- Proceed from position 1 through 3 in sequence

- Hold each position for 3 seconds

- As the exercises become easier to complete, increase the number of repetitions, or how many times per day you do them

Step-by-step directions for Series A

- With your hand in front of you and your wrist straight, fully straighten all of your fingers (1)

- Bend the tips of your fingers into the “hook” position with your knuckles pointing up (2)

- Make a tight fist with your thumb over your fingers (3)

Step-by-step directions for Series B

- With your hand in front of you and your wrist straight, fully straighten all of your fingers (1)

- Make a “tabletop” with your fingers by bending at your bottom knuckle and keeping the fingers straight (2)

- Bend your fingers at the middle joint, touching your fin-gers to your palm (3)

Figure 15. Carpal tunnel tendon glides

Surgical treatment

If nonsurgical treatment does not relieve your symptoms after a period of time, your doctor may recommend surgery. The goal of carpal tunnel surgery is to relieve pressure by cutting the ligament pressing on the median nerve.

The decision whether to have surgery is based on the severity of your symptoms—how much pain and numbness you are having in your hand. In long-standing cases with constant numbness and wasting of your thumb muscles, surgery may be recommended to prevent irreversible damage.

Surgical procedure

The surgical procedure performed for carpal tunnel syndrome is called a “carpal tunnel release.” There are two different surgical techniques for doing this, but the goal of both is to relieve pressure on your median nerve by cutting the ligament that forms the roof of the tunnel. This increases the size of the tunnel and decreases pressure on the median nerve.

In most cases, carpal tunnel surgery is done on an outpatient basis. The surgery can be done under general anesthesia, which puts you to sleep, or under local anesthesia, which numbs just your hand and arm. In some cases, you will also be given a light sedative through an intravenous (IV) line inserted into a vein in your arm.

- Open carpal tunnel release. In open surgery, your doctor makes a small incision in the palm of your hand and views the inside of your hand and wrist through this incision. During the procedure, your doctor will divide the transverse carpal ligament (the roof of the carpal tunnel). This increases the size of the tunnel and decreases pressure on the median nerve. After surgery, the ligament may gradually grow back together—but there will be more space in the carpal tunnel and pressure on the median nerve will be relieved.

- Endoscopic carpal tunnel release. In endoscopic surgery, your doctor makes one or two smaller skin incisions—called portals—and uses a miniature camera—an endoscope—to see inside your hand and wrist. A special knife is used to divide the transverse carpal ligament, similar to the open carpal tunnel release procedure.

The outcomes of open surgery and endoscopic surgery are similar. There are benefits and potential risks associated with both techniques. Your doctor will talk with you about which surgical technique is best for you.

Recovery

Immediately following surgery, you will be encouraged to elevate your hand above your heart and move your fingers to reduce swelling and prevent stiffness.

You should expect some pain, swelling, and stiffness after your procedure. Minor soreness in your palm may last for several weeks to several months.

Grip and pinch strength usually return by about 2 to 3 months after surgery. If the condition of your median nerve was poor before surgery, however, grip and pinch strength may not improve for about 6 to 12 months.

You may have to wear a splint or wrist brace for several weeks. You will, however, be allowed to use your hand for light activities, taking care to avoid significant discomfort. Driving, self-care activities, and light lifting and gripping may be permitted soon after surgery.

Your doctor will talk with you about when you will be able to return to work and whether you will have any restrictions on your work activities.

Surgery Complications

Although complications are possible with any surgery, your doctor will take steps to minimize the risks. The most common complications of carpal tunnel release surgery include:

- Bleeding

- Infection

- Nerve aggravation or injury

Outcomes

For most patients, surgery will improve the symptoms of carpal tunnel syndrome. Recovery, however, may be gradual and complete recovery may take up to a year.

If you have significant pain and weakness for more than 2 months, your doctor may refer you to a hand therapist who can help you maximize your recovery.

If you have another condition that causes pain or stiffness in your hand or wrist, such as arthritis or tendonitis, it may slow your overall recovery. In long-standing cases of carpal tunnel syndrome with severe loss of feeling and/or muscle wasting around the base of the thumb, recovery will also be slower. For these patients, a complete recovery may not be possible.

Occasionally, carpal tunnel syndrome can recur, although this is rare. If this happens, you may need additional treatment or surgery.

Femoral nerve compression

A painful, burning sensation on the outer side of the thigh may mean that one of the large sensory nerves to your legs—the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve is being compressed. This condition is known as meralgia paresthetica.

Meralgia paresthetica is a condition characterized by tingling, numbness and burning pain in your outer thigh. The cause of meralgia paresthetica is compression of the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve that supplies sensation to the skin surface of your thigh.

Tight clothing, obesity or weight gain, and pregnancy are common causes of meralgia paresthetica. However, meralgia paresthetica can also be due to local trauma or a disease, such as diabetes.

In most cases, you can relieve meralgia paresthetica with conservative measures, such as wearing looser clothing. In severe cases, treatment may include medications to relieve discomfort or, rarely, surgery.

Figure 16. Femoral nerve compression

Femoral nerve compression causes

Meralgia paresthetica occurs when the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve — which supplies sensation to the surface of your outer thigh — becomes compressed, or pinched. The lateral femoral cutaneous nerve is purely a sensory nerve and doesn’t affect your ability to use your leg muscles.

In most people, this nerve passes through the groin to the upper thigh without trouble. But in meralgia paresthetica, the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve becomes trapped — often under the inguinal ligament, which runs along your groin from your abdomen to your upper thigh.

Common causes of this compression include any condition that increases pressure on the groin, including:

- Tight clothing, such as belts, corsets and tight pants

- Obesity or weight gain

- Wearing a heavy tool belt

- Pregnancy

- Scar tissue near the inguinal ligament due to injury or past surgery

Nerve injury, which can be due to diabetes or seat belt injury after a motor vehicle accident, for example, also can cause meralgia paresthetica.

Risk factors for femoral nerve compression

The following might increase your risk of meralgia paresthetica:

- Extra weight. Being overweight or obese can increase the pressure on your lateral femoral cutaneous nerve.

- Pregnancy. A growing belly puts added pressure on your groin, through which the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve passes.

- Diabetes. Diabetes-related nerve injury can lead to meralgia paresthetica.

- Age. People between the ages of 30 and 60 are at a higher risk.

Femoral nerve compression symptoms

Pressure on the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve, which supplies sensation to your upper thigh, might cause these symptoms of meralgia paresthetica:

- A burning sensation, tingling and numbness in the outer (lateral) part of your thigh

- Burning pain on the surface of the outer part of your thigh, occasionally extending to the outer side of the knee

- Occasionally, aching in the groin area or pain spreading across the buttocks

- Usually only on one side of the body

- Usually more sensitive to light touch than to firm pressure

These symptoms commonly occur on one side of your body and might intensify after walking or standing.

Femoral nerve compression diagnosis

In most cases, your doctor can make a diagnosis of meralgia paresthetica based on your medical history and a physical exam. He or she might test the sensation of the affected thigh, ask you to describe the pain, and ask you to trace the numb or painful area on your thigh. Additional examination including strength testing and reflex testing might be done to help exclude other causes for the symptoms.

To rule out other conditions, your doctor might recommend:

- Imaging studies. Although no specific changes are evident on X-ray if you have meralgia paresthetica, images of your hip and pelvic area might be helpful to exclude other conditions as a cause of your symptoms. If your doctor suspects a tumor could be causing your pain, he or she might order a CT scan or MRI.

- Electromyography. This test measures the electrical discharges produced in muscles to help evaluate and diagnose muscle and nerve disorders. A thin needle electrode is placed into the muscle to record electrical activity. Results of this test are normal in meralgia paresthetica, but the test might be needed to exclude other disorders when the diagnosis isn’t clear.

- Nerve conduction study. Patch-style electrodes are placed on your skin to stimulate the nerve with a mild electrical impulse. The electrical impulse helps diagnose damaged nerves. This test might be done primarily to exclude other causes for the symptoms.

- Nerve blockade. Pain relief achieved from anesthetic injection into your thigh where the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve enters into it can confirm that you have meralgia paresthetica. Ultrasound imaging might be used to guide the needle.

Femoral nerve compression treatment

Treatments will vary, depending on the source of the pressure. For most people, the symptoms of meralgia paresthetica ease in a few months. Treatment focuses on relieving nerve compression.

The goal is to remove the cause of the compression. This may mean resting from an aggravating activity, losing weight, wearing loose clothing, or using a toolbox instead of wearing a tool belt.

It may take time for the burning pain to stop and, in some cases, numbness will persist despite treatment. In more severe cases, your doctor may give you an injection of a corticosteroid preparation to reduce inflammation. This generally relieves the symptoms for some time. In rare cases, surgery is needed to release the nerve.

Conservative measures

Conservative measures include:

- Wearing looser clothing

- Losing excess weight

- Taking OTC pain relievers such as acetaminophen (Tylenol, others), ibruprofen (Advil, Motrin IB, others) or aspirin

Medications

If symptoms persist for more than two months or your pain is severe, treatment might include:

- Corticosteroid injections. Injections can reduce inflammation and temporarily relieve pain. Possible side effects include joint infection, nerve damage, pain and whitening of skin around the injection site.

- Tricyclic antidepressants. These medications might relieve your pain. Side effects include drowsiness, dry mouth, constipation and impaired sexual functioning.

- Gabapentin (Gralise, Neurontin), phenytoin (Dilantin) or pregabalin (Lyrica). These anti-seizure medications might help lessen your painful symptoms. Side effects include constipation, nausea, dizziness, drowsiness and lightheadedness.

Surgery

Rarely, surgery to decompress the nerve is considered. This option is only for people with severe and long-lasting symptoms.

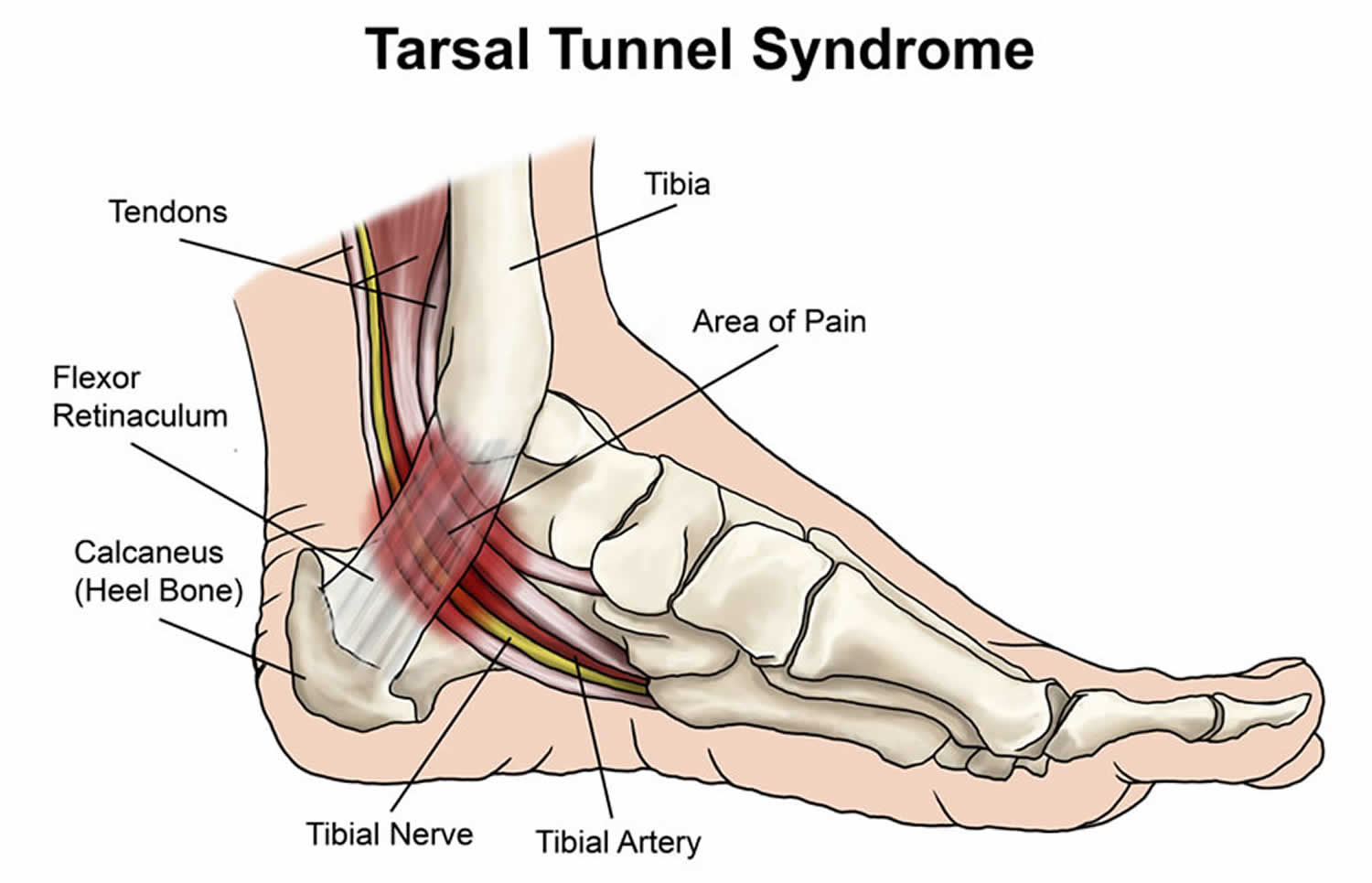

Nerve compression in foot

Tarsal tunnel syndrome, sometimes referred to as tibial nerve dysfunction or posterior tibial nerve neuralgia, is an entrapment neuropathy that is associated with the compression of the structures within the tarsal tunnel 21. Tarsal tunnel syndrome is similar to carpal tunnel syndrome of the wrist although much less common 22.

The tarsal tunnel is a narrow fibro-osseous space that runs behind and inferior to the medial malleolus. It is bounded by the medial malleolus anterosuperiorly, by the posterior talus and calcaneus laterally, and is held against the bone by the flexor retinaculum which extends from the medial malleolus to the medial calcaneus and prevents medial displacement of its contents.

The tarsal tunnel is a narrow space that lies on the inside of the ankle next to the ankle bones. The tunnel is covered with a thick ligament (the flexor retinaculum) that protects and maintains the structures contained within the tunnel—arteries, veins, tendons and nerves. One of these structures is the posterior tibial nerve, which is the focus of tarsal tunnel syndrome.

The tarsal tunnel includes multiple important structures. It contains the tendons of the posterior tibialis, flexor digitorum longus (FDL), and flexor hallucis longus (FHL) muscles. The posterior tibial artery and vein, as well as posterior tibial nerve (L4-S3), also pass through it. The orientation of these structures within the tarsal tunnel is noteworthy. From medial to lateral, they are the tibialis posterior tendon, FDL tendon, posterior tibial artery and vein, posterior tibial nerve, and FHL tendon.

The posterior tibial nerve passes between the FDL and FHL muscles before it bifurcates in the tarsal tunnel, forming the medial and lateral plantar nerves. In 5% of people, the bifurcation occurs before the tarsal tunnel. The medial plantar nerve passes deep to the abductor hallucis and FHL muscles and provides sensation to the medial half of the foot and first 3.5 digits and motor function to the lumbricals, abductor hallucis, flexor digitorum brevis, and flexor hallucis brevis. The lateral plantar nerve passes directly through the abductor hallucis muscle belly and provides sensory innervation of the medial calcaneus and lateral heel and motor function to the flexor digitorum brevis, quadratus plantae, and abductor digiti minimi. The medial calcaneal nerve typically branches off of the posterior tibial nerve proximal to the tarsal tunnel and provides sensory innervation to the posteromedial heel. In 25% of patients, it branches off of the lateral plantar nerve or runs superficial to the flexor retinaculum.

Figure 17. Tarsal tunnel syndrome

Figure 18. Tarsal tunnel anatomy

Figure 19. Tibial nerve (posterior tibial nerve and branches)

Tarsal tunnel syndrome causes

Tarsal tunnel syndrome is an unusual form of peripheral neuropathy. Tarsal tunnel syndrome occurs when there is damage to the tibial nerve.

The area in the foot where the nerve enters the back of the ankle is called the tarsal tunnel. This tunnel is normally narrow. When the tibial nerve is compressed, it results in the symptoms of tarsal tunnel syndrome.

Pressure on the tibial nerve may be due to any of the following:

- Swelling from an injury, such as a sprained ankle or nearby tendon

- An abnormal growth, such as a bone spur, lump in the joint (ganglion cyst), swollen (varicose) vein

- Flat feet or a high arch

- Body-wide (systemic) diseases, such as diabetes, low thyroid function, arthritis

In some cases, no cause can be found.

Tarsal tunnel syndrome symptoms

Patients with tarsal tunnel syndrome experience one or more of the following symptoms:

- Shooting pain in the foot

- Numbness

- Tingling or burning sensation

- Pain and tingling around the ankle

- Swelling in the foot

- Pain radiating up into the leg or down into the ankle and foot

- Pins and needles feeling in the foot

Symptoms are typically felt on the inside of the ankle and/or on the bottom of the foot. In some people, a symptom may be isolated and occur in just one spot. In others, it may extend to the heel, arch, toes and even the calf.

Sometimes the symptoms of the syndrome appear suddenly. They are often brought on or aggravated by overuse of the foot, such as in prolonged standing, walking, exercising or beginning a new exercise program.

It is important to seek early treatment if any of the symptoms of tarsal tunnel syndrome occur. If left untreated, the condition progresses and may result in permanent nerve damage. In addition, because the symptoms of tarsal tunnel syndrome can be confused with other conditions, proper evaluation is essential so that a correct diagnosis can be made and appropriate treatment initiated.

Tarsal tunnel syndrome diagnosis

Proper diagnosis of a tarsal tunnel syndrome requires the expert attention of experienced foot and ankle surgeon.

During your medical examination, the surgeon will position your foot and tap on the nerve to see if the symptoms can be reproduced. He or she will also press on the area to help determine if a small mass is present.

Advanced imaging studies may be ordered if a mass is suspected or if initial treatment does not reduce the symptoms. Studies used to evaluate nerve problems—electromyography and nerve conduction velocity (EMG/nerve conduction study)—may be ordered if the condition shows no improvement with nonsurgical treatment.

Tarsal tunnel syndrome test will include:

- Electrical testing (EMG or nerve conduction study)

- Imaging (X-rays, CT, or MRI scans)

Diagnosis is necessary to determine the severity of the condition, so the appropriate treatment plan, including a surgical option, can be considered.

Tarsal tunnel syndrome treatment

Nonsurgical treatment for tarsal tunnel syndrome

Whenever possible, doctors will prescribe nonsurgical treatment options before surgery is recommended. Possible treatment options may include anti-inflammatory medications or steroid injections into the nerves in the tarsal tunnel to relieve pressure and swelling. Orthosis (e.g., braces, splints, orthotic devices) may be recommended to reduce pressure on the foot and limit movement that could cause compression on the nerve.

Many treatment options, often used in combination, are available to treat tarsal tunnel syndrome. These include:

- Rest. Staying off the foot prevents further injury and encourages healing.

- Ice. Apply an ice pack to the affected area, placing a thin towel between the ice and the skin. Use ice for 20 minutes and then wait at least 40 minutes before icing again.

- Oral medications. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as ibuprofen, help reduce the pain and inflammation.

- Immobilization. Restricting movement of the foot by wearing a cast is sometimes necessary to enable the nerve and surrounding tissue to heal.

- Physical therapy. Ultrasound therapy, exercises and other physical therapy modalities may be prescribed to reduce symptoms.

- Injection therapy. Injections of a local anesthetic provide pain relief, and an injected corticosteroid may be useful in treating the inflammation.

- Orthotic devices. Custom shoe inserts may be prescribed to help maintain the arch and limit excessive motion that can cause compression of the nerve.

- Shoes. Supportive shoes may be recommended.

- Bracing. Patients with flatfoot or those with severe symptoms and nerve damage may be fitted with a brace to reduce the amount of pressure on the foot.

Tarsal tunnel syndrome surgery

The foot and ankle surgeon will determine if surgery is necessary and will select the appropriate procedure or procedures based on the cause of the condition. Depending on the severity of the condition, one of several surgical options may be recommended, including tarsal tunnel release.

Complications are associated with tarsal tunnel decompression surgery may include nerve or artery laceration and plantar fasciitis 23. One small study reviewed the results of 30 patients who underwent decompression surgery for tarsal tunnel syndrome and reported a 13 percent complication rate 24. In this study, three individuals had wound infections and one person had a delay in wound healing.

- Chung KC. Treatment of ulnar nerve compression at the elbow. J Hand Surg Am. 2008;33(9):1625–1627. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2008.06.024 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4410271[↩]

- Chauhan M, M Das J. Cubital Tunnel Syndrome. [Updated 2019 Apr 1]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2019 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538259[↩]

- Filippou G, Mondelli M, Greco G, Bertoldi I, Frediani B, Galeazzi M, Giannini F. Ulnar neuropathy at the elbow: how frequent is the idiopathic form? An ultrasonographic study in a cohort of patients. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2010 Jan-Feb;28(1):63-7[↩]

- Treatment of ulnar neuropathy at the elbow: cost-utility analysis. Song JW, Chung KC, Prosser LA. J Hand Surg Am. 2012 Aug; 37(8):1617-1629.e3[↩]

- Natural history and conservative management of cubital tunnel syndrome. Szabo RM, Kwak C. Hand Clin. 2007 Aug; 23(3):311-8, v-vi.[↩]

- Devi BI, Konar SK, Bhat DI, Shukla DP, Bharath R, Gopalakrishnan MS. Predictors of Surgical Outcomes of Traumatic Peripheral Nerve Injuries in Children: An Institutional Experience. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2018;53(2):94-99[↩]

- Buchanan BK, Varacallo M. Radial Nerve Entrapment. [Updated 2018 Oct 27]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2019 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK431097[↩]

- Agarwal A, Chandra A, Jaipal U, Saini N. A panorama of radial nerve pathologies- an imaging diagnosis: a step ahead. Insights Imaging. 2018;9(6):1021-1034. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6269333/[↩]

- Kameda Y. An anomalous muscle (accessory subscapularis-teres-latissimus muscle) in the axilla penetrating the brachial plexus in man. Acta Anat (Basel) 1976;96:513–533. doi: 10.1159/000144700.[↩]

- Spinner M. Management of nerve compression lesions of the upper extremity. In: Omer GE Jr, Spinner M, editors. Management of Peripheral Nerve Problems. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1980. pp. 569–587.[↩]

- Lotem M, Fried A, Levy M, Solzi P, Najenson T, Nathan H. Radial palsy following muscular effort: a nerve compression syndrome possibly related to a fibrous arch of the lateral head of the triceps. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1971;53:500–506. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.53B3.500.[↩]

- Lubahn JD, Lister GD. Familial radial nerve entrapment syndrome: a case report and literature review. J Hand Surg Am. 1983;8:297–299. doi: 10.1016/S0363-5023(83)80163-4.[↩]

- Mayer RF, Garcia-Mullin R. Hereditary neuropathy manifested by pressure palsies: Schwann cell disorder? Trans Am Neurol Assoc. 1968;93:238–240.[↩]

- Moradi A, Ebrahimzadeh MH, Jupiter JB. Radial tunnel syndrome, diagnostic and treatment dilemma. Arch Bone Jt Surg. 2015;3(3):156–162.[↩]

- Woltman HW, Learmonth JR (1934) Progressive paralysis of the nervous interosseous dorsalis. Brain 57:25–31[↩]

- Hazani R, Engineer NJ, Mowlavi A, Neumeister M, Lee WPA, Wilhelmi BJ. Anatomic landmarks for the radial tunnel. Eplasty. 2008;8:e37.[↩]

- Olewnik Ł, Podgórski M, Polguj M, Wysiadecki G, Topol M. Anatomical variations of the pronator teres muscle in a Central European population and its clinical significance. Anat Sci Int. 2018 Mar;93(2):299-306[↩]

- Brown JM, Yablon CM, Morag Y, Brandon CJ, Jacobson JA. US of the Peripheral Nerves of the Upper Extremity: A Landmark Approach. Radiographics. 2016 Mar-Apr;36(2):452-63[↩]

- Sigamoney KV, Rashid A, Ng CY. Management of Atraumatic Posterior Interosseous Nerve Palsy. J Hand Surg Am. 2017 Oct;42(10):826-830[↩]

- Bertelli J, Soldado F, Ghizoni MF. Outcomes of Radial Nerve Grafting In Children After Distal Humerus Fracture. J Hand Surg Am. 2018 Dec;43(12):1140.e1-1140.e6.[↩]

- Kiel J, Kaiser K. Tarsal Tunnel Syndrome. [Updated 2019 Feb 4]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2019 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513273[↩]

- Calvo-Lobo C, Painceira-Villar R, López-López D, García-Paz V, Becerro-de-Bengoa-Vallejo R, Losa-Iglesias ME, Palomo-López P. Tarsal Tunnel Mechanosensitivity Is Increased in Patients with Asthma: A Case-Control Study. J Clin Med. 2018 Dec 12;7,12[↩]

- Tarsal Tunnel Syndrome. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1236852-overview[↩]

- Pfeiffer WH, Cracchiolo A 3rd. Clinical results after tarsal tunnel decompression. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1994;76:1222-1230[↩]