Occipital neuralgia

Occipital neuralgia is a painful condition affecting the posterior head in the distributions of the greater occipital nerve, lesser occipital nerve, third occipital nerve or a combination of the three 1. Occipital neuralgia is a distinct type of headache characterized by piercing, throbbing, or electric-shock-like chronic pain in the upper neck, back of the head, and behind the ears, usually on one side of the head lasting from seconds to minutes. Typically, the pain of occipital neuralgia begins in the neck and then spreads upwards. Some individuals will also experience pain in the scalp, forehead, and behind the eyes. Their scalp may also be tender to the touch, and their eyes especially sensitive to light. The location of pain is related to the areas supplied by the greater and lesser occipital nerves, which run from the area where the spinal column meets the neck, up to the scalp at the back of the head (see Figure 1 below). The pain is caused by irritation or injury to the occipital nerves, which can be the result of trauma to the back of the head, pinching of the occipital nerves by overly tight neck muscles, compression of the occipital nerve as it leaves the spine due to osteoarthritis, or tumors or other types of lesions in the neck. Localized inflammation or infection, gout, diabetes, blood vessel inflammation (vasculitis), and frequent lengthy periods of keeping the head in a downward and forward position are also associated with occipital neuralgia. In many cases, however, no cause can be found. A positive response (relief from pain) after an anesthetic nerve block will confirm the diagnosis.

There are multiple treatment modalities, several of which have well-established efficacy in treating occipital neuralgia. Occipital neuralgia treatment is generally symptomatic and includes massage and rest. In some cases, antidepressants may be used when the pain is particularly severe. Other treatments may include local nerve blocks and injections of steroids directly into the affected area.

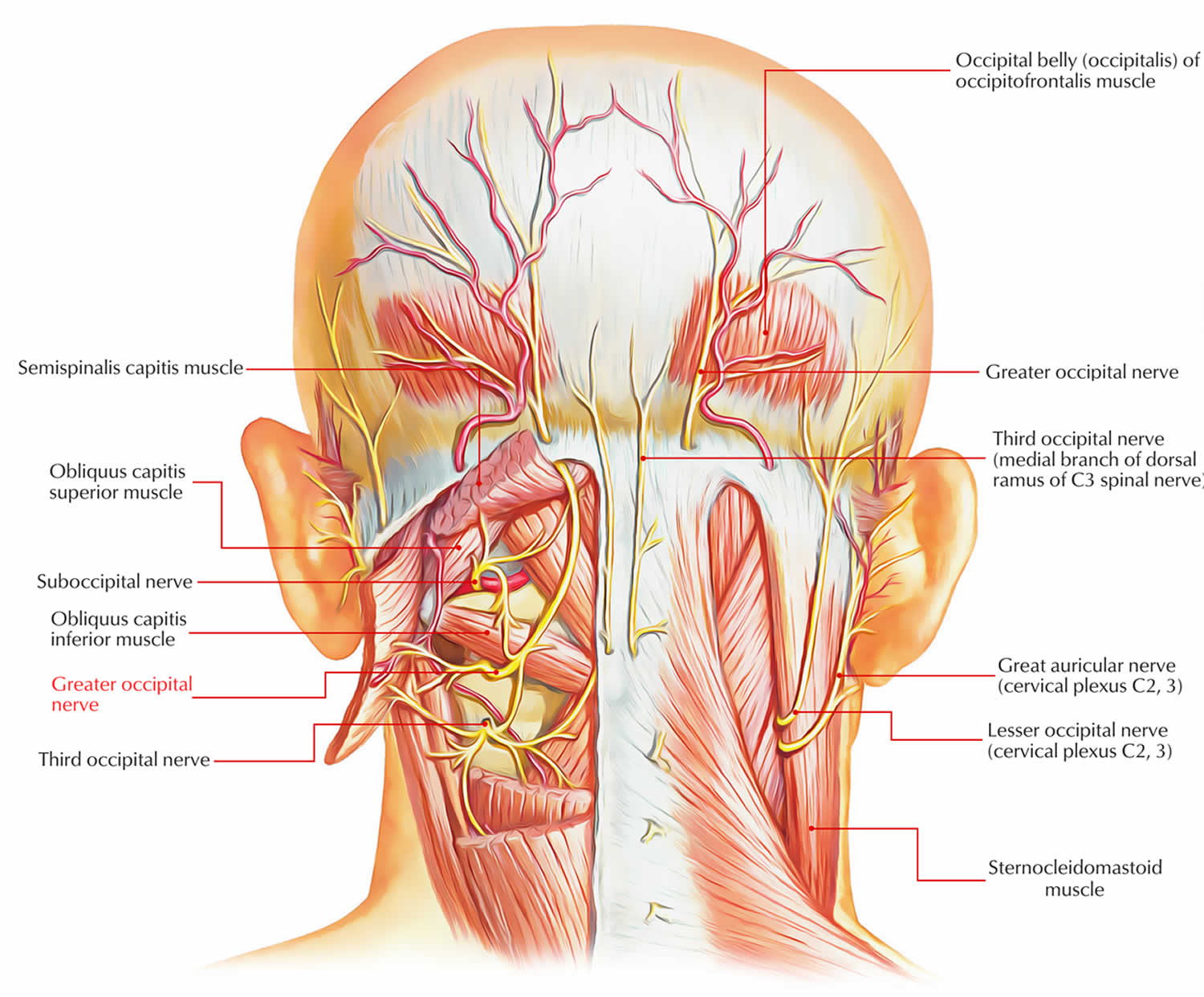

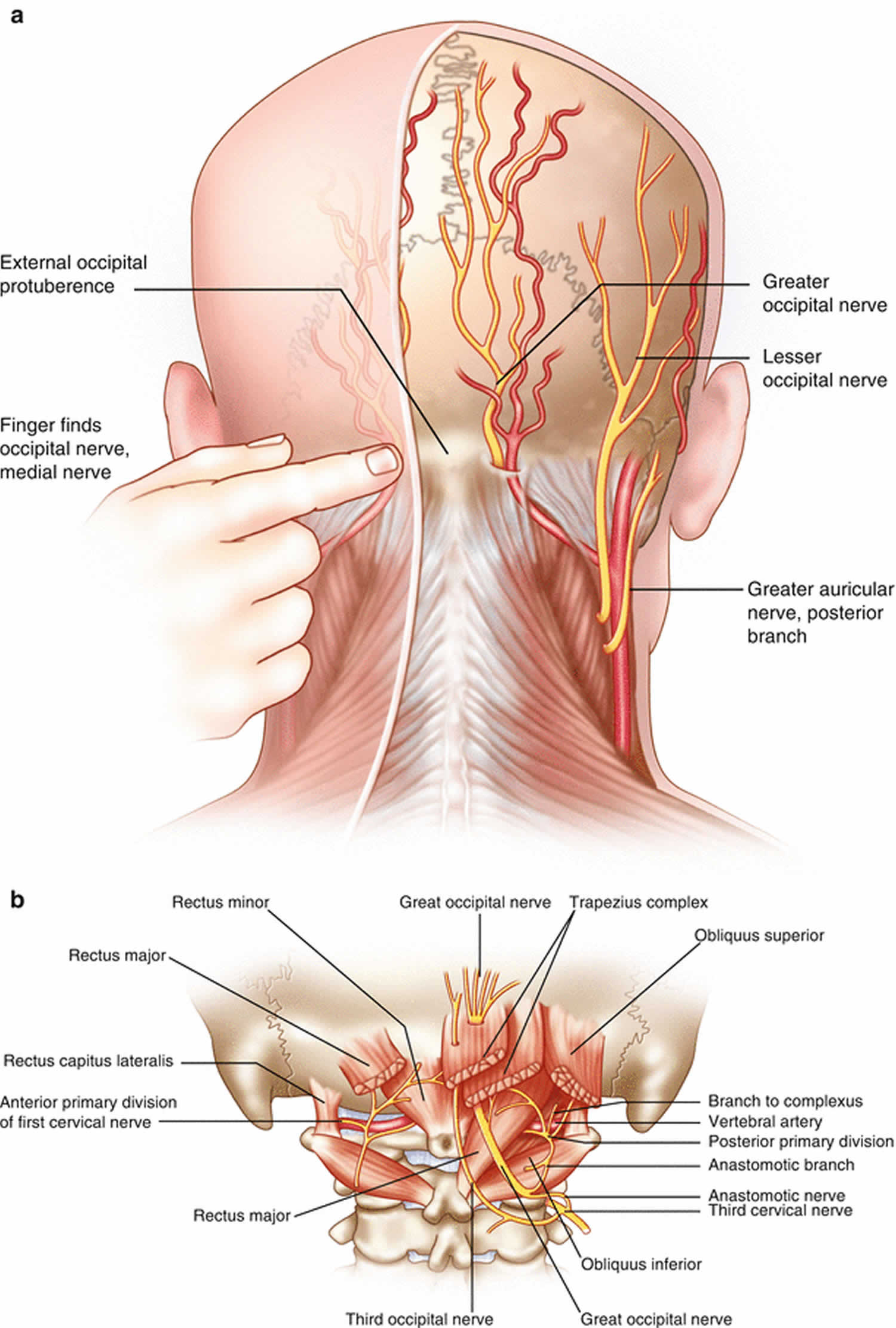

Figure 1. Occipital nerve

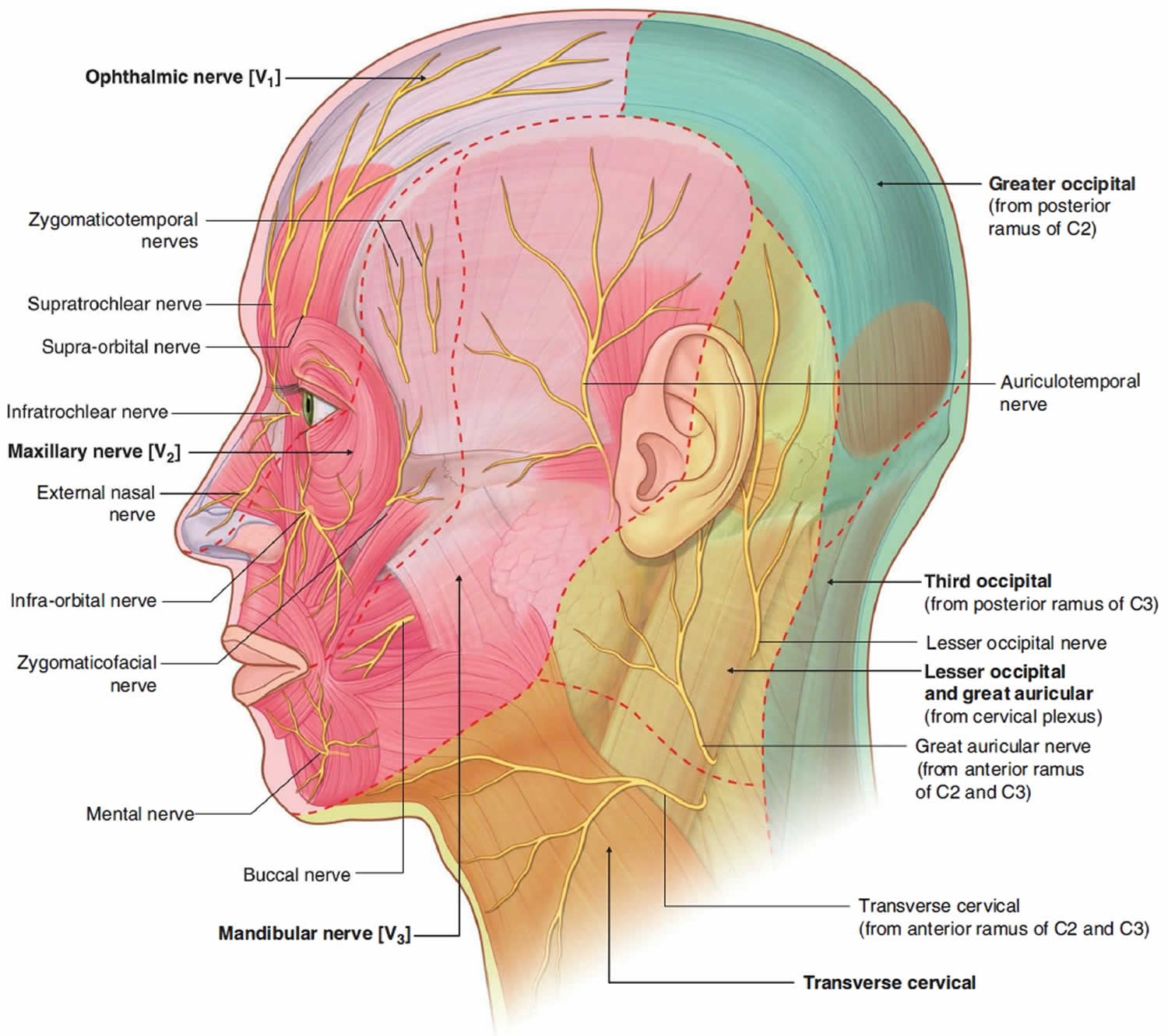

Figure 2. Occipital nerve sensory distribution

Occipital nerve anatomy

- Lesser occipital nerve is also a branch of the cervical plexus, arises from the anterior ramus of the C2 spinal nerve, ascends on the posterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle, and supplies an area of the scalp posterior and superior to the ear.

- Greater occipital nerve is a branch of the posterior ramus of the C2 spinal nerve, emerges just inferior to the obliquus capitis inferior muscle, ascends superficial to the suboccipital triangle, pierces the semispinalis capitis and trapezius muscles, and then spreads out to supply a large part of the posterior scalp as far superiorly as the vertex.

- Third occipital nerve is a branch of the posterior ramus of the C3 spinal nerve, pierces the semispinalis capitis and trapezius muscles, and supplies a small area of the lower part of the scalp.

Most feeling in the back and top of the head is transmitted to the brain by the two greater occipital nerves. There is one nerve on each side of the head. Emerging from between bones of the spine in the upper neck, the two greater occipital nerves make their way through muscles at the back of the head and into the scalp. They sometimes reach nearly as far forward as the forehead, but do not cover the face or the area near the ears; other nerves supply these regions.

Irritation of one of these nerves anywhere along its course can cause a shooting, zapping, electric, or tingling pain very similar to that of trigeminal neuralgia, only with symptoms on one side of the scalp rather than in the face. Sometimes the pain can also seem to shoot forward (radiate) toward one eye. In some patients the scalp becomes extremely sensitive to even the lightest touch, making washing the hair or lying on a pillow nearly impossible. In other patients there may be numbness in the affected area. The region where the nerves enter the scalp may be extremely tender.

How common is occipital neuralgia?

True isolated occipital neuralgia is actually quite rare. However, many other types of headaches —especially migraines — can predominantly or repeatedly involve the back of the head on one particular side, inflaming the greater occipital nerve on the involved side and causing confusion as to the actual diagnosis. These patients are generally diagnosed as having migraines involving the greater occipital nerve, rather than as having occipital neuralgia itself.

In one study investigating the incidence of facial pain in a Dutch population, occipital neuralgia comprised 8.3% of facial pain cases. The total incidence of occipital neuralgia was 3.2 per 100,000 people, with a mean age of diagnosis of 54.1 years (standard deviation of 16.2 years) 2.

Occipital neuralgia causes

Occipital neuralgia is a result of greater occipital nerve pathophysiology in 90% of cases 1. Ten percent of cases are due to lesser occipital nerve causes, and rarely is the third occipital nerve thought to be involved 1. Occipital neuralgia almost always results from the compression of one of these nerves at one of several anatomic points. In fact, for the various neuralgias described in the International Classification of Headache Disorders, Third Edition (ICHD-3), in the majority of cases many of the traditional neuralgias are no longer considered to result from primary nerve pathophysiology (e.g., herpes zoster, other infections, demyelinating lesions).

Rarely, other sensory cutaneous nerves may overlap the typical distribution area of the occipital nerves. In one case report, the suboccipital nerve supplied a cutaneous branch in the normal distribution of the greater occipital nerve 3. Such variations could contribute to unremitting neuralgia in that region.

Occipital neuralgia may occur spontaneously, or as the result of a pinched nerve root in the neck (from arthritis, for example), tumor, trauma, infection, systemic disease, hemorrhage or because of prior injury or surgery to the scalp or skull. Sometimes “tight” muscles at the back of the head can entrap the nerves.

Any of the following may be causes of occipital neuralgia, many cases can be attributed to chronic neck tension or unknown origins.

- Osteoarthritis of the upper cervical spine

- Trauma to the greater and/or lesser occipital nerves

- Compression of the greater and/or lesser occipital nerves or C2 and/or C3 nerve roots from degenerative cervical spine changes

- Cervical disc disease

- Tumors affecting the C2 and C3 nerve roots

- Gout

- Diabetes

- Blood vessel inflammation

- Infection.

Occipital neuralgia differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for occipital neuralgia includes any disorder which similarly presents with a headache or facial pain. Because connections are possible between the occipital nerves and cranial nerves VIII, IX, and X, patients can sometimes present with confusing symptoms, such as vision impairment, dizziness, or sinus congestion 4. The conditions most easily mistaken with occipital neuralgia for other headache and facial pain disorders, including migraine, cluster headache, tension headache, and hemicrania continua. Mechanical neck pain from an upper disc, facet, or musculoligamentous sources may refer into the occiput, but is not classically lancinating or otherwise neuropathic and should not be confused with occipital neuralgia. A crucial step in differentiating occipital neuralgia from other disorders is relief with an occipital nerve block.

Occipital neuralgia symptoms

Occipital neuralgia symptoms include continuous aching, burning and throbbing, with intermittent shocking or shooting pain. The pain often is described as migraine-like and some patients experience other symptoms common to migraines and cluster headaches. The pain usually originates at the base of the skull and radiates near the back or along the side of the scalp. Some patients experience pain behind the eye on the affected side. The pain is felt most often on one side of the head, but may also affect both sides of the head. Neck movements may trigger pain in some patients. The scalp may be tender to the touch, and an activity like brushing the hair may increase a person’s pain.

Occipital neuralgia diagnosis

It can be difficult to distinguish occipital neuralgia from other types of headaches — thus, diagnosis may be challenging. There is not one test to diagnose occipital neuralgia. A thorough evaluation will include a medical history, physical examination and diagnostic tests. A doctor can document symptoms and determine the extent to which these symptoms affect a patient’s daily living. If there are abnormal findings on a neurological exam, the doctor may order the following tests:

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI): A diagnostic test that produces three-dimensional images of body structures using powerful magnets and computer technology; can show direct evidence of spinal cord impingement from bone, disc or hematoma.

- Computed tomography scan (CT or CAT scan): A diagnostic image created after a computer reads x-rays; can show the shape and size of the spinal canal, its contents and the structures around it.

Your doctor may make a diagnosis using a physical examination to find tenderness in response to pressure along your occipital nerve. Your doctor may diagnose — and temporarily treat — with an occipital nerve block. Relief with a nerve block may help to confirm the diagnosis. For patients who do well with this temporary “deadening” of the occipital nerve, a more permanent procedure may be a good option.

Occipital neuralgia treatment

The goal of occipital neuralgia treatment is to alleviate the pain. Often, symptoms will improve or disappear with heat, rest and/or physical therapy, including massage, anti-inflammatory medications and muscle relaxants. The most conservative treatments, such as immobilization of the neck by cervical collar, physiotherapy, and cryotherapy have not been shown to perform better than placebo 5. Oral anticonvulsant medications such as carbamazepine and gabapentin also may help alleviate pain.

Percutaneous nerve blocks not only may be helpful in diagnosing occipital neuralgia, but they can help alleviate pain as well. Nerve blocks involve either the occipital nerves or, in some patients, the C2 and/or C3 ganglion nerves. Medications and a set of three steroid injections, with or without botulinum toxin, can “calm down” the overactive nerves. It is important to keep in mind that the use of steroids in nerve block treatment may cause serious adverse effects.

Botulinum Toxin A injection has emerged as a treatment with a conceptually lower side effect profile than many other techniques described here, with most recent trials demonstrating 50% or more improvement 4.

Some patients respond well to non-invasive therapy and may not require surgery; however, some patients do not get relief and may eventually require surgical treatment.

There are other treatment options such as burning the nerve with a radio-wave probe or eliminating the nerve with a small dose of toxin. However, these are not always the best choice since either treatment can permanently deaden the nerve, resulting in scalp numbness.

Occipital neuralgia medication

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), tricyclic antidepressants, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, and anticonvulsants may help to alleviate symptoms.

Oral anticonvulsant medications such as carbamazepine and gabapentin also may help alleviate pain.

Interventional procedures

There are several advanced interventional procedures in clinical use 1:

- Pulsed or thermal radiofrequency ablation (RFA) may be considered for longer lasting relief after local anesthetic blockade confirms the diagnosis. Thermal radiofrequency ablation aimed at destroying the nerve architecture can render long-term analgesia but also comes with the potential risks of hypesthesia, dysesthesia, anesthesia dolorosa, and painful neuroma formation. Chemical neurolysis with alcohol or phenol carries the same risks as thermal radiofrequency ablation 6. There is no such risk with pulsed radiofrequency ablation, however, some question its efficacy as compared to other procedures.

- Neuromodulation of the occipital nerve(s) involves placement of nerve stimulator leads in a horizontal or oblique orientation at the base of the skull across where the greater occipital nerve emerges. Patients should be trialed with temporary leads first, and greater than 50% pain relief for several days is considered a successful trial after which permanent implantation may be considered. Risks include surgical site infection and lead or generator displacement or fracture after the operation 4.

- Ultrasound-guided percutaneous cryoablation of the greater occipital nerve is commonly performed by the article’s editor. At the correct temperature there should be stunning but not permanent damage of the nerve, but at temperatures below negative 70 degrees Celsius nerve injury is possible. Most recently in the literature, a 2018 article by Kastler et al. 7 described 7 patients who underwent cryoneurolysis in a non-blinded fashion to good effect, but the follow-up was limited to 3 months. Some authors have seen between 3 months to 1.5 years of benefit (typically around 6 months) with each treatment 1.

Surgery

Surgical decompression is often considered to be the last resort. Surgical intervention may be considered when the pain is chronic and severe and does not respond to conservative treatment. The benefits of surgery should always be weighed carefully against its risks.

In one study of 11 patients, only two patients did not experience significant pain relief postoperatively and mean pain episodes per month decreased from 17.1 to 4.1, with mean pain intensity scores also decreasing from 7.18 to 1.73 8. Resection of part of the obliquus capitis inferior muscle has shown success in patients who have an exacerbation of their pain with flexion of the cervical spine 4. Another popular surgical technique is C2 gangliotomy, even though patients are left with several days of intermittent nausea and dizziness 5. As with any large nerve resection, there is a theoretical risk of developing a deafferentation syndrome, though arguably the risk is lower if the resection is pre-ganglionic.

Occipital release surgery

Surgical options include decompression of the greater occipital nerves along their course, called occipital release surgery.

In this outpatient procedure, the surgeon makes an incision in the back of the neck to expose the greater occipital nerves and release them from the surrounding connective tissue and muscles that may be compressing them. The surgeon can address other nerves that may be contributing to the problem, such as the lesser occipital nerves and the dorsal occipital nerves.

The surgery generally takes around two or three hours and is performed with the patient asleep under general anesthesia. Patients are able to go home the same day, and full recovery is generally expected within one or two weeks.

In some cases, occipital release surgery only works temporarily, and the pain returns. Further surgery to cut the greater occipital nerves can be performed after about a year, however, this procedure is regarded as a last resort since it would result in permanent scalp numbness.

Microvascular decompression

Microvascular decompression involves microsurgical exposure of the affected nerves, identification of blood vessels that might be compressing the nerves and gentle displacement of these away from the point of compression. “Decompression” may reduce sensitivity and allow the nerves to recover and return to a normal, pain-free condition. The nerves treated may include the C2 nerve root, ganglion and postganglionic nerve.

Occipital nerve stimulation uses a neuro-stimulator to deliver electrical impulses via insulated lead wires tunneled under the skin near the occipital nerves at the base of the head. The electrical impulses can help block pain messages to the brain. The benefit of this procedure is that it is minimally invasive, and the nerves and other surrounding structures are not permanently damaged.

Occipital neuralgia complications

Complications from procedures have been reported in the literature. In a case series reviewing over a hundred thermal radiofrequency ablation procedures, one patient developed intraventricular hemorrhage and died after the case, which the authors attribute to hypertension during the procedure 5. The same paper reported a patient who developed Brown-Sequard syndrome from post-traumatic cervical syringomyelia, also after radiofrequency ablation.

Occipital neuralgia prognosis

Occipital neuralgia is not a life-threatening condition. Many individuals will improve with therapy involving heat, rest, anti-inflammatory medications, and muscle relaxants. Recovery is usually complete after the bout of pain has ended and the nerve damage repaired or lessened. Rarely, diagnostic injections of local anesthetic with or without steroid can yield up to several months of analgesia 4. Advanced treatments mentioned above may result in improvements of ranging from weeks to years.

- Djavaherian DM, Guthmiller KB. Occipital Neuralgia. [Updated 2019 Jun 4]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538281[↩][↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Koopman JS, Dieleman JP, Huygen FJ, de Mos M, Martin CG, Sturkenboom MC. Incidence of facial pain in the general population. Pain. 2009 Dec 15;147(1-3):122-7.[↩]

- Lake S, Iwanaga J, Oskouian RJ, Loukas M, Tubbs RS. A Case Report of an Enlarged Suboccipital Nerve with Cutaneous Branch. Cureus. 2018 Jul 06;10(7):e2933.[↩]

- Choi I, Jeon SR. Neuralgias of the Head: Occipital Neuralgia. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2016 Apr;31(4):479-88.[↩][↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Finiels PJ, Batifol D. The treatment of occipital neuralgia: Review of 111 cases. Neurochirurgie. 2016 Oct;62(5):233-240.[↩][↩][↩]

- Greher M, Moriggl B, Curatolo M, Kirchmair L, Eichenberger U. Sonographic visualization and ultrasound-guided blockade of the greater occipital nerve: a comparison of two selective techniques confirmed by anatomical dissection. Br J Anaesth. 2010 May;104(5):637-42.[↩]

- Kastler A, Attyé A, Maindet C, Nicot B, Gay E, Kastler B, Krainik A. Greater occipital nerve cryoneurolysis in the management of intractable occipital neuralgia. J Neuroradiol. 2018 Oct;45(6):386-390.[↩]

- Jose A, Nagori SA, Chattopadhyay PK, Roychoudhury A. Greater Occipital Nerve Decompression for Occipital Neuralgia. J Craniofac Surg. 2018 Jul;29(5):e518-e521.[↩]