Omental infarction

Omental infarction is rare cause of acute abdomen which occurs because of focal torsion or lack of blood flow to a portion of the omentum 1. Omental infarction signs and symptoms can mimic other acute intra-abdominal conditions like appendicitis and cholecystitis. Having both acute appendicitis and omental infarction is extremely rare with only two cases reported in the literature: one in an adult female 2 and the other in a 7-year-old girl 3. Although omental infarction is considered a benign condition, typical symptoms are severe and can prolong return to activities of daily living for many weeks.

Omental infarction is a rare cause of acute abdomen with reported incidence being less than 4 per 1000 cases of appendicitis 4. Omental infarction usually presents as right-sided abdominal pain although seldomly causing left-sided abdominal pain and even epigastric pain 5. The dominion of right-sided abdominal pain in omental infarction has been attributed to right segmental infarction as a result of the tenuous blood vessels in this part of the omentum as well as its longer size and higher mobility in comparison to the left side which subjects it to torsion 6. Obesity is a known risk factor for omental infarction. The theory behind this is that fat accumulation within the omentum occludes blood supply to the distal parts of the omentum in addition to making it more susceptible to torsion 7. Other risk factors for omental infarction are polycythemia, hypercoagulability, and vasculitides plus other conditions which predispose to torsion such as trauma, sudden body movements, coughing, heavy food intake, and hyperperistalsis 7.

Historically, omental infarction was diagnosed only intraoperatively during surgery for presumed appendicitis or other causes of acute abdomen. But with the increase in the use of imaging, especially abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan in the work-up for acute abdomen, more cases of omental infarction are being diagnosed preoperatively 1. This has also led to the observation that omental infarction is a self-limiting condition which can be managed conservatively. Currently, conservative management and surgery are the only treatment options for omental infarction with no consensus as to the best treatment modality 1.

Omental infarction causes

Primary omental infarction

Pathogenesis relating to blood supply disruption in idiopathic omental infarction is unknown 8. The classic location of primary omental infarction is in the right lower quadrant medial to the ascending colon or cecum 9. The vascular compromise occurs along the right edge of the greater omentum where the arterial supply is usually tenuous. In view of a preponderance for right side presentations 10, it has been suggested that the right half of the omentum consists of anatomically altered vasculature, less tolerant of spontaneous venous stasis and thrombosis secondary to stretching of omental veins 11. Interestingly a raised body mass index (BMI) has been of particular interest, on the back of cases reporting idiopathic omental infarction in obese children. It is hypothesised that fatty accumulation in the omentum impedes the distal right epiploic artery, and additional structural mass potentially precipitates torsion 12.

Sometimes it is the result from kinking of venous channels in the inferior part of the greater omentum in the pelvis. Occasionally omentum twists on itself resulting in omental torsion leading to both arterial and venous compromise. The omentum may infarct without torsion, and this is called as primary idiopathic segmental infarction 13.

Secondary omental infarction

- post surgery

- abdominal trauma

- omental inflammation

Both primary omental infarction and infarction secondary to torsion have been reported in children 14. Precipitating factors are thought to include trauma, overexertion, bifid omentum, overeating and coughing 15. In one patient, primary torsion of the omentum was reported in a jackhammer worker, and was considered to be a vibration-related injury 16. It was interesting to note that a patient with torsion and infarction of the epiploic appendix of the transverse colon was a jackhammer worker who had performed a heavier load of work than normal the day before the admission 13. This confirms the possible role of vibration in the development of torsion and infarction of the abdominal appendages in general.

Despite being rare, more cases of omental infarction are being reported in recent literature due to the increasing availability and use of imaging modalities especially CT scan in the work-up for acute abdomen 17 leading to more cases being diagnosed preoperatively unlike in the past where only 0.6% to 4.8% of omental infarction were diagnosed nonoperatively 4.

Risk factors for omental infarction

Obesity is a known risk factor for omental infarction. The theory behind this is that fat accumulation within the omentum occludes blood supply to the distal parts of the omentum in addition to making it more susceptible to torsion 7. Other risk factors for omental infarction are polycythemia, hypercoagulability, and vasculitides plus other conditions which predispose to torsion such as trauma, sudden body movements, coughing, heavy food intake, and hyperperistalsis 7.

Omental infarction symptoms

Patients may present with 18:

- sudden onset of abdominal pain

- right lower quadrant pain and tenderness

- absence of fever and gastrointestinal symptoms

- encountered in healthy patients, such as marathoners, because of low omental blood flow

Omental infarction usually presents as right-sided abdominal pain although seldomly causing left-sided abdominal pain and even epigastric pain 5.

Omental infarction diagnosis

Primary omental infarction is usually seen in the right lower quadrant. Secondary omental infarction is located at the site of initial insult. It is usually larger than 5 cm, which helps distinguishing it from epiploic appendagitis 18.

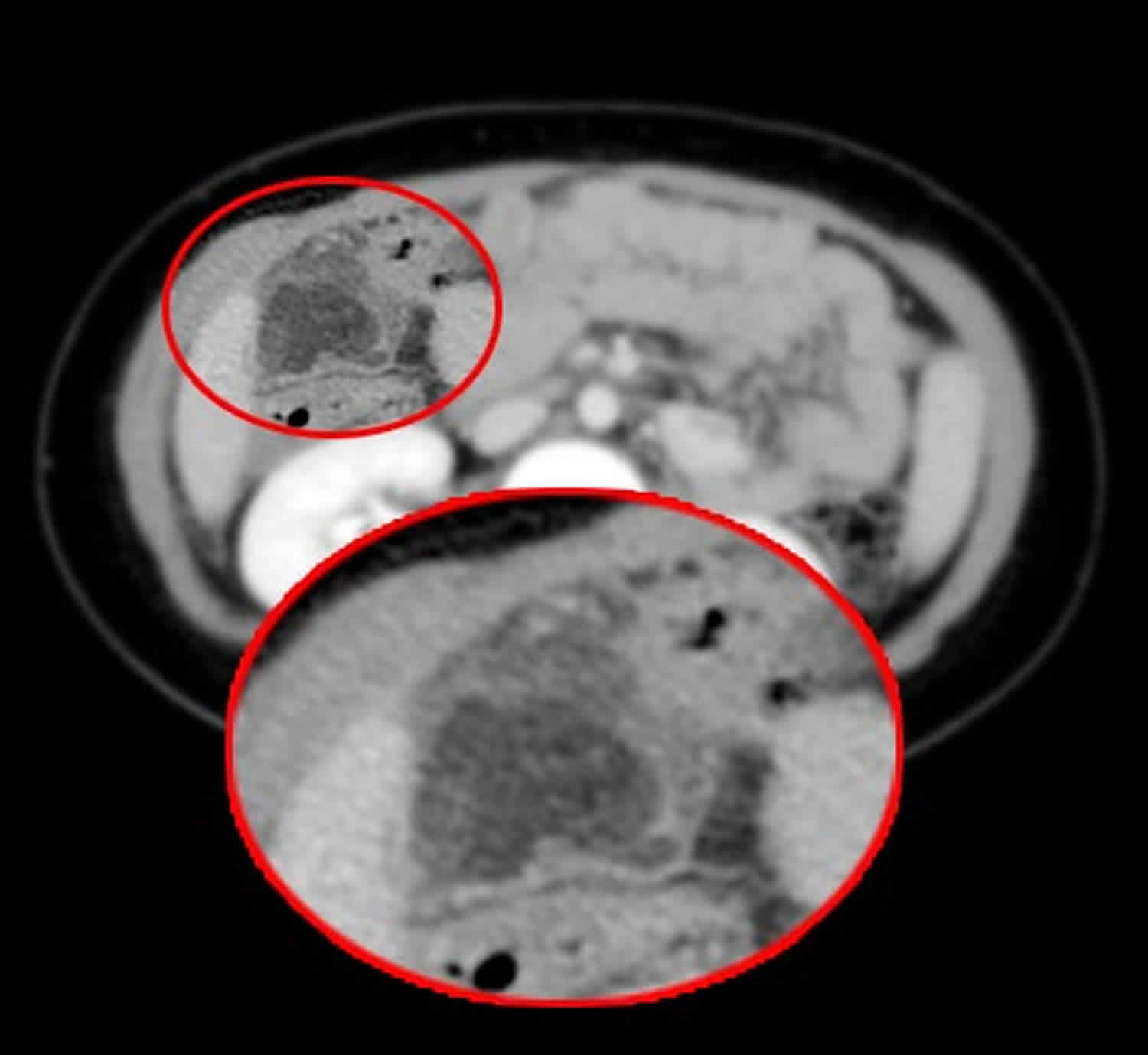

Radiological features of omental infarction are not straightforward as seen in a case and also as reported by Itenberg et al. 4. The two most common imaging modalities used are abdominal ultrasound and CT scans. Sonographic features suggestive of omental infarction are a noncompressible hyperechoic ovoid mass, while CT scan findings include the classic “whirl sign” (whirling patterns of fat and vessels in the omentum) and concentric linear strands or caking of the omental fat 7. Additionally, free peritoneal fluid is seen as was for our patient 19. However, none of these features except for the “whirl sign” is specific enough to diagnose omental infarction, and ultrasound scan is operator dependent with a reported sensitivity of 64%, while CT scan despite having a much better sensitivity of 90% is interpreter dependent requiring experience 4.

Ultrasound

- focal area of increased echogenicity in the omental fat

CT scan findings

- focal area of fat stranding

- swirling of omental vessels in omental torsion

- hyperdense peripheral halo

Omental infarction treatment

Two treatment options exist for omental infarction: conservative/medical management and surgical intervention, which is usually done laparoscopically. Omental infarction is often self-limiting and can be managed conservatively. Occasionally complications such as abscess formation occur which require surgery or radiological drainage.

Omental infarction conservative treatment

Currently, there is no consensus on the best treatment modality, but with increasing preoperative diagnosis, conservative treatment has gained popularity since omental infarction is seen as a self-limiting condition 7. After CT imaging diagnosis, Itenburg et al. 20:44–47.)) advocate close monitoring of a patient in the first 24–48 hours, refraining from considering surgery until deterioration in any symptom, sign or clinical marker. To what extent a change is significant enough to precipitate surgery is an arbitrary judgement. This approach employs analgesics, anti-inflammatory drugs, and occasionally antibiotics, and a number of case series have reported success 17. However, complications do occur albeit rarely with conservative management. These include prolonged/worsening pain, abscess formation, adhesions, and intestinal obstruction 21.

The proponents of surgical approach argue that surgery (usually laparoscopic) expedite the resolution of symptoms and shorten hospital stay in addition to preventing the complications associated with conservative treatment 7. However, there is no denying the risks associated with any surgical intervention.

In the rare case of omental infarction occurring simultaneously with another more serious acute abdominal pathology like appendicitis as in our patient, surgical intervention is the treatment approach of choice. Both two cases reported in literature thus far 2, 3 and another patient had appendectomy and resection of the infarcted omentum 1. Koay and Mahmoud 3, did laparoscopic appendectomy and resection of the necrotic omentum while Battaglia et al. 2 did open appendectomy and resection of the omentum. In all three cases, the patients had uneventful recovery but the hospital stay was much shorter: 2 days for the two patients who had laparoscopy compared to 5 days for the patient who underwent open surgery.

Laparoscopy not only aids in the treatment of omental infarction but also can be diagnostic where it can be missed preoperatively with the radiological imaging. Had the authors done an open appendectomy with McBurney’s incision, there is every possibility that the patient would have continued to have postoperative symptoms leading to prolonged hospital stay as well as requiring further diagnostics and intervention to manage the same. Hence, laparoscopy is clearly superior in diagnosis, management, and resultant shorter hospital stay with resolution of symptoms.

Omental infarction recovery

Omental infarction is often self-limiting and can be managed conservatively. Occasionally complications such as abscess formation occur which require surgery or radiological drainage.

Currently, there is no consensus on the best treatment modality, but with increasing preoperative diagnosis, conservative treatment has gained popularity since omental infarction is seen as a self-limiting condition 7. This approach employs analgesics, anti-inflammatory drugs, and occasionally antibiotics, and a number of case series have reported success 17. However, complications do occur albeit rarely with conservative management. These include prolonged/worsening pain, abscess formation, adhesions, and intestinal obstruction 21.

The proponents of surgical approach argue that surgery (usually laparoscopic) expedite the resolution of symptoms and shorten hospital stay in addition to preventing the complications associated with conservative treatment 7. Koay and Mahmoud 3, did laparoscopic appendectomy and resection of the necrotic omentum while Battaglia et al. 2 did open appendectomy and resection of the omentum. In all three cases, the patients had uneventful recovery but the hospital stay was much shorter: 2 days for the two patients who had laparoscopy compared to 5 days for the patient who underwent open surgery.

- Mani VR, Razdan S, Orach T, et al. Omental Infarction with Acute Appendicitis in an Overweight Young Female: A Rare Presentation. Case Rep Surg. 2019;2019:8053931. Published 2019 Apr 7. doi:10.1155/2019/8053931 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6476035[↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Battaglia L., Belli F., Vannelli A., et al. Simultaneous idiopathic segmental infarction of the great omentum and acute appendicitis: a rare association. World Journal of Emergency Surgery. 2008;3(1):p. 30. doi: 10.1186/1749-7922-3-30[↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Koay H. T., Mahmoud H. E. Simultaneous omental infarction and acute appendicitis in a child. The Medical journal of Malaysia. 2015;70(1):42–44.[↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Itenberg E., Mariadason J., Khersonsky J., Wallack M. Modern management of omental torsion and omental infarction: a surgeon’s perspective. Journal of Surgical Education. 2010;67(1):44–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2010.01.003[↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Walia R., Verma R., Copeland N., Goubeaux D., Pabby S., Khan R. Omental infarction: an unusual cause of left-sided abdominal pain. ACG Case Reports Journal. 2014;1(4):223–224. doi: 10.14309/crj.2014.60[↩][↩]

- Lindley SI, Peyser PM. Idiopathic omental infarction: One for conservative or surgical management?. J Surg Case Rep. 2018;2018(3):rjx095. Published 2018 Mar 26. doi:10.1093/jscr/rjx095 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5868192[↩]

- Barai K. P., Knight B. C. Diagnosis and management of idiopathic omental infarction: a case report. International Journal of Surgery Case Reports. 2011;2(6):138–140. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2011.02.014[↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Barai KP, Knight BC. Diagnosis and management of idiopathic omental infarction: A case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2011;2(6):138–140. doi:10.1016/j.ijscr.2011.02.014 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3199678[↩]

- Battaglia L., Belli F., Vannelli A., Bonfanti G., Gallino G., Poiasina E. Simultaneous idiopathic segmental infarction of the great omentum and acute appendicitis: a rare association. World J Emerg Surg. 2008;3(October):30.[↩]

- Puylaert J.B. Right-sided segmental infarction of the omentum: clinical, US, and CT findings. Radiology. 1992;185(October (1):169–172.[↩]

- Danikas D., Theodorou S., Espinel J., Schneider C. Laparoscopic treatment of two patients with omental infarction mimicking acute appendicitis. JSLS. 2001;5(January–March (1):73–75.[↩]

- Fragoso A.C., Pereira J.M., Estevão-Costa J. Nonoperative management of omental infarction: a case report in a child. J Pediatr Surg. 2006;41(October (10):1777–1779.[↩]

- Al-Jaberi TM, Gharaibeh KI, Yaghan RJ. Torsion of abdominal appendages presenting with acute abdominal pain. Ann Saudi Med. 2000 May-July;20(3-4):211-3. https://doi.org/10.5144/0256-4947.2000.211[↩][↩]

- Kimber CP, Westmore P, Hutson JM, Kelly JH. “Primary omental torsion in children” . J Paediatr Child Health. 1996; 32:22–4.[↩]

- Basson SE, Jones PA. “Primary torsion of the omentum” . Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1981; 63:132–4.[↩]

- Shields PG, Chase KH. “Primary torsion of the omentum in a jackhammer operator: another vibration-related injury” . J Occup Med. 1988; 30:892–4.[↩]

- Park T. U., Oh J. H., Chang I. T., et al. Omental infarction: case series and review of the literature. The Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2012;42(2):149–154. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2008.07.023[↩][↩][↩]

- Kamaya A, Federle MP, Desser TS. Imaging manifestations of abdominal fat necrosis and its mimics. Radiographics. 31 (7): 2021-34. doi:10.1148/rg.317115046[↩][↩]

- Cianci R., Filippone A., Basilico R., Storto M. L. Idiopathic segmental infarction of the greater omentum diagnosed by unenhanced multidetector-row CT and treated successfully by laparoscopy. Emergency Radiology. 2007;15(1):51–56. doi: 10.1007/s10140-007-0631-z[↩]

- Itenberg E., Mariadason J., Khersonsky J., Wallack M. Modern management of omental torsion and omental infarction: a surgeon’s perspective. J Surg Educ. 2010;67(January–February (1[↩]

- Rimon A., Daneman A., Gerstle J. T., Ratnapalan S. Omental infarction in children. The Journal of Pediatrics. 2009;155(3):427–431.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.03.039[↩][↩]