Onychoschizia

Onychoschizia also known as onychoschisis or lamellar dystrophy, is a term for nail splitting or splitting of the distal lamella of the nail horizontally at the free edge, is a condition that causes horizontal splits within the nail plate 1. Onychoschizia is often seen together with onychorrhexis, a long-wise (longitudinal) splitting or ridging of the nail plate and these 2 nail conditions together are called “brittle nail syndrome.” Onychoschizia is more common in women and older individuals. Onychoschizia is often due to frequent water or detergent exposure 2. People in occupations requiring frequent wetting and drying of the hands are at increased risk for nail splitting; therefore, onychoschizia is common among house cleaners, nurses, and hairdressers. Nail splitting may also be caused by nail cosmetics (hardeners, polish, polish removers/solvents), nail procedures, and occupational exposure to various chemicals (alkalis, acids, cement, solvents, thioglycolates, salt, sugar solutions). Injury (trauma) may also play a role in the development of brittle nails. Only very rarely are internal disease or vitamin deficiencies the reason (iron deficiency is the most common). Brittle nails may occur due to medical problems, including gland (endocrine system) diseases, tuberculosis, Sjögren syndrome, and malnutrition. People with other skin diseases, such as lichen planus and psoriasis, as well as people taking oral medications made from vitamin A, may also develop nail splitting.

One tip is that if the fingernails split, but the toenails are strong, then an external factor is the cause. Basically brittle nails can be divided into dry and brittle (too little moisture) and soft and brittle (often too much moisture).

The usual cause is repeated wetting and drying of the fingernails. This makes them dry and brittle. This is often worse in low humidity and in the winter (dry heat). Treatment of onychoschizia can be difficult; however, preventative measures and/or oral supplements can be useful in improving nail strength. The best treatment is to apply lotions containing alpha-hydroxy acids or lanolin containing lotions such as “Elon” to the nails after first soaking nails in water for 5 minutes.

Wearing gloves when performing household chores that involve getting the hands wet is very helpful in preventing brittle nails. Cotton lined rubber gloves can be purchased in stores.

If soft, consider that the nails may be getting too much moisture or being damaged by chemicals such as detergents, cleaning fluids and nail polish removers (the acetone containing removers are somewhat worse than acetone free). Some feel that once a week application of clear nail prep once a week may help. Nail polishes with nylon fibers in them may add strength.

Be gentle to you nails. Shape and file the nails with a very fine file and round the tips in a gentle curve. Daily filing of snags or irregularities helps to prevent further breakage or splitting. Avoid metal instruments on the nail surface to push back the cuticle. If the nails are “buffed” do this in the same direction as the nail grows and not in a “back and forth” motion because this can cause nail splitting.

Biotin (a vitamin) taken by mouth is beneficial in some people. Get the “Biotin ultra” 1 mg. size as it also comes as much smaller pills and take 2 or 3 a day. It takes at least 6 months, but does really help at least 1/3 of the time. Do not take this if you are pregnant. Calcium, colloidal minerals, and/or gelatin my help, but have not been shown to help as reliably as Biotin.

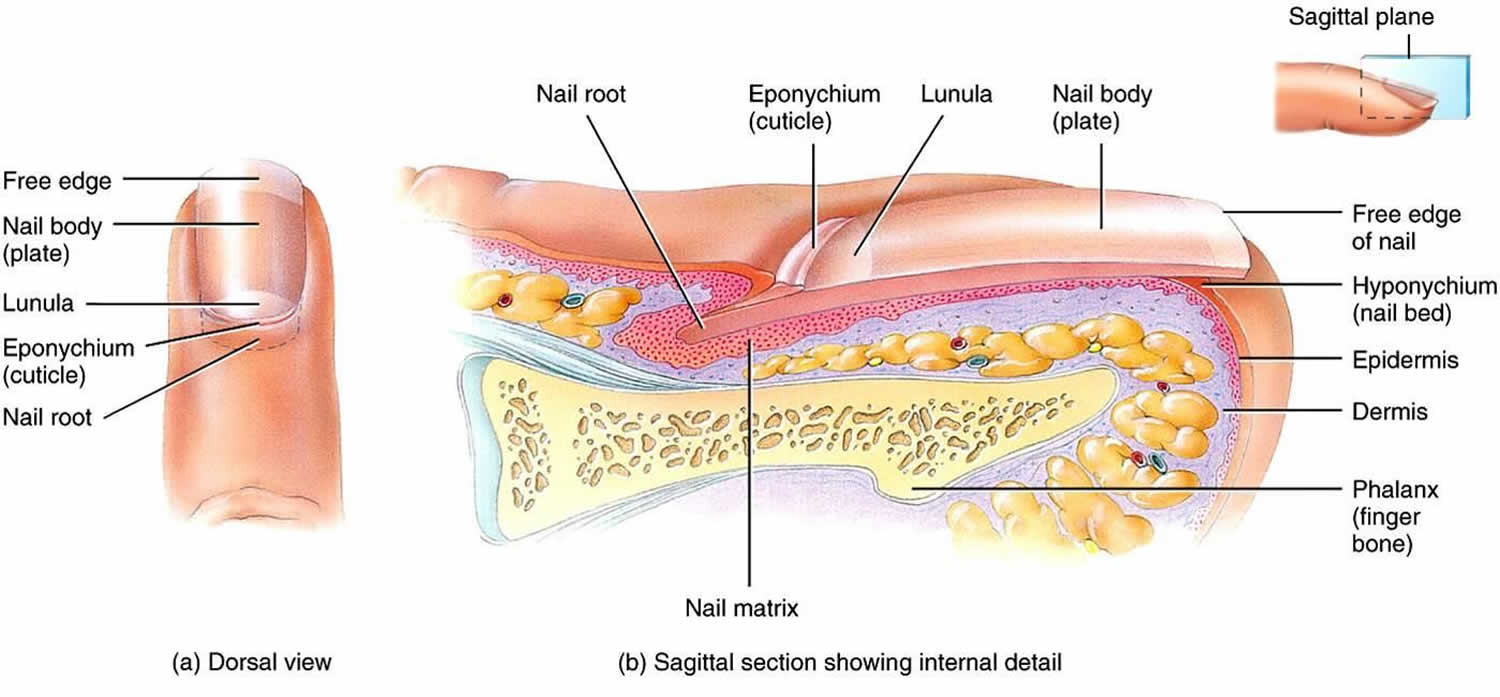

Figure 1. Nail anatomy

Figure 2. Onychoschizia

Figure 2. Onychoschizia nails

Onychoschizia causes

Although little information is available about the cause of onychoschizia, it is commonly the result of repeated trauma, such as excessive immersion in water with detergents, or the recurrent application of nail polish 3. In addition, the frequent use of solvents to remove nail polish can further dehydrate the nail 3. One study examined the in vitro (test tube study) nail changes produced by acidic and basic solutions, detergents, water, organic solvents, and other polar materials. It was found that nail clippings exposed to water with alternate periods of drying developed the most prominent lamellar separation. Basic solutions caused some softening, but lamellar separation was only observed after repeated hydration and dehydration 4.

Other factors associated with onychoschizia can include old age, systemic diseases, drugs and nutritional deficiencies 5. For example, onychoschizia has been reported to be associated with polycythemia vera 6 and ibrutinib treatment for chronic lymphocytic leukemia has been linked to onychoschizia 7. Dietary deficiencies of certain vitamins and minerals, including iron, zinc and selenium can cause nail alterations leading to onychoschizia 8. This suggests that the correct intake of vitamins and minerals is essential for normal nail growth and function.

There are 2 forms of nail fragility: a primary “idiopathic” form and nail fragility secondary to different causes 9. Primary brittle nails are speculated to develop from the impairment of intercellular adhesive factors of the nail matrix or abnormalities in epidermal growth and keratinization. Brittle nails of secondary origin are typically linked to disordered keratinization from dermatologic disease or systemic disorders, such as endocrine, metabolic, or vascular abnormalities. Other precipitating factors for brittle nails include the repetitive wetting and drying of the hands, direct contact with chemicals (nail polish remover), trauma to the nail, and onychomycosis 10.

Causes of brittle nails include:

- Idiopathic Nail Brittleness (Brittle Nail Syndrome): This is the most common cause of nail brittleness, almost exclusively seen in the fingernails. In women, the intercellular keratinocyte bridges are constitutionally weaker than in males and this can be considered a cause of the higher frequency of this complaint among females. Moreover, normal nails contain 5% lipids and there is a decrease in cholesterol sulphate of the nail plate with age, especially in post-menopausal women, suggesting an important role of lipids in the development of nail brittleness 11. Some authors have identified reduced water content in the nail plate (< 16%) as a possible cause of brittle nails 12. In contrast, other studies found no significant difference in water content of brittle compared with normal nails 13.

- Secondary Nail Brittleness:

- Secondary to impairment of intercellular adhesive factors of the nail plate:

- exogenous factors

- immersion/desiccation – in occupations such as nursing, and hairdressing, where repetitive wetting and drying of the hands

- chemicals – in particular, occupational exposure to thioglycolates, solvents, cement, acids, alkalis, anilines, salt, and sugar solutions

- trauma – for example typing, telephone dialing, improper nail clipping (also trauma caused by excessive length of the nails)

- fungi – fungal infections may cause both intracellular and intercellular fractures in the nail plate

- exogenous factors

- Secondary to pathologic nail formation

- Causes of pathologic nail formation resulting in brittle nails include:

- endocrine and metabolic diseases such as hypopituitarism, hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism, hypoparathyriodism, acromegaly, diabetes mellitus, gout, osteoporosis, osteomalacia, pregnancy, and malnutrition (anorexia nervosa, bulimia)

- decreased nail formation has been observed after radiation or arsenic intoxication

- reduced vascularization and oxygenation directly affect epidermal growth and keratinization

conditions that have been associated with brittle nails in this context include, arteriosclerosis and age-related decrease of circulation, microangiopathy, Raynaud’s disease, anemia, polycythemia vera (polycythemia causing sludge formation), major chronic infectious diseases (pulmonary tuberculosis, empyema, bronchiectasis), and sarcoidosis - disordered keratinization may impair nail plate formation

- if a self-limiting impairment of short duration, nail pits or spots of leuconychia may be seen

- involvement of the entire nail plate or longitudinal involvement occur secondary to processes that have impaired the nail matrix during prolonged periods – conditions that may cause such involvement include Darier’s disease, pityriasis rubra pilaris, lichen planus, and alopecia areata – these conditons may cause longitudinal ridges, longitudinal splits, or sandpaper-like nails

- psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, and mycoses may lead to a thickened nail plate with a brittle appearance

- nail growths/tumours (such as melanoma, squamous cell carcinoma, warts) are diagnosed after removal of the nail plate – however the nail plate may show longitudinal abnormalities indicative of brittlenes

- Causes of pathologic nail formation resulting in brittle nails include:

- Secondary to impairment of intercellular adhesive factors of the nail plate:

Inflammatory nail disorders

Several dermatoses such as psoriasis, lichen planus, lichen striatus, alopecia areata, Darier’s disease and eczema may involve the nail apparatus 14. Usually these disorders are diagnosed as separate entities although features of nail fragility are common in these patients.

In fact, up to 50% of patients affected by psoriasis present nail abnormalities that are frequently associated with nail brittleness. When the proximal part of the nail matrix is involved, the nail plate presents irregular and deep pits, while a more extensive psoriatic involvement of the nail matrix induces a friable and brittle nail plate 15.

Lichen planus in its various forms can also affect the nails. About 10% of patients with lichen planus have specific nail involvement 16. Depending on the degree of inflammation, the nail changes consist of thinning, longitudinal ridging and splitting of the nail plate (Figure 4). Rarely, erosive lichen planus may involve the nails 17. In lichen striatus, nail involvement is similar to that of lichen planus, but typically only half of the nail plate is affected 18.

Approximately 2/3 of patients with alopecia areata have nail changes, such as pits secondary to proximal nail matrix involvement, onychorrhexis, thinning and trachyonychia. Changes may be seen in one, several or all the nails.

Periungual eczema, seen in contact dermatitis or atopic dermatitis, is frequently associated with nail plate fragility.

Infections

Superficial white onychomycosis is an example of a cause of nail fragility secondary to nail plate damage. In this type of onychomycosis, the fungal hyphae colonize the most superficial layers of the nail plate, and it becomes white, opaque, and friable in multiple small spots secondary to keratin digestion by fungi 19.

In distal subungual onychomycosis, fungi invade the nail bed from the distal free margin of the nail plate, inducing nail fragility in the distal portion.

Several infectious diseases such as syphilis and pulmonary tuberculosis can give nonspecific alterations to the nails such as nail thinning and fissuring of the free margin and an overall fragility 20.

Systemic diseases and general conditions

Brittle nails have also been linked with systemic diseases, nutritional deficiencies and medication ingestion, but they are often only a non-specific sign that accompanies these conditions 13.

The impairment of peripheral circulation secondary to arteriopathy, neurological disorders, chronic anemia and arteriosclerosis may lead to a reduced nail matrix vascularization with production of a thin nail plate 21.

Patients with endocrine disorders may present with brittle nails, slow nail growth and longitudinal ridging and fissuring. Nail changes, characterized by brittleness and softness, are present in about 5% of cases of hyperthyroidism and are often reversible following successful therapy. The nails are affected in 90% of patients with hypothyroidism and typically appear thin, brittle, slow-growing and with longitudinal or transverse striae 22.

Onycholysis, increased fragility, longitudinal ridging and crumbling may occur in amyloidosis.

Systemic medications such as cancer chemotherapeutic agents, retinoids or antiretrovirals may be responsible for lamellar onychoschizia.

A severe deficiency of vitamins, trace elements and aminoacids from daily food intake may result in nail fragility and thinning 23.

Traumas and alteration of nail hydration

Traumas significantly contribute to damage of the nail plate and alteration of the nail plate surface. Nail fragility can be caused by mechanical micro-traumas secondary to routine professional activities, as in homemakers, housemaids, shoemakers, ironworkers, and carpenters. Occupational exposure to solvents and solutions (chemical/medical personnel, photographers or painters, for example) can dissolve intercellular lipids and damage intercellular cohesion. Onychotillomania (a compulsive neurosis in which a person picks constantly at the nails or tries to tear them off) and onychophagia are another two causes of traumatic brittle nails.

The methods used to prepare nails for cosmesis and all methods of removing the applied preparations damage the healthy nail plates. However, the application of nail polish itself does not cause an alteration of the pH of the nail lamina, being approximately 5.8, which is very close to the physiological value 24. Water is stored above all in the ventral portion of the nail plate and the alteration of water content of the nail plate could cause brittle nails (Fig. 12). Dehydration is more rapid if nails are not kept short 25. Moreover, hydration and desiccation may play a significant role in household employees, hairdressers, and nurses where repeated wetting and drying of the hands leads to fractures between nail plate onychocytes.

Finally, occlusive gloves applied over wet hands while working may be a cause of brittle nails, leading to splintered, fractured nails and onychoschisis 26.

Onychoschizia symptoms

Onychoschizia or nail splitting affects the fingernails and the toenails. Onychoschizia may appear as a single horizontal split between layers of the nail plate at the growing end or as multiple splits and loosening of the growing edge of the nail plate.

Horizontal nail splitting may occur along with onychorrhexis, with longitudinal ridging or splitting as well.

Horizontal splits at the origin of the nail plate may be seen in people with psoriasis or lichen planus or in people who use oral medications made from vitamin A.

Onychoschizia diagnosis

A thorough review of systems and a review of medical history and medications should direct subsequent workup to assess for potential systemic causes. The following medical history elements are helpful in creating a differential diagnosis:

- Occupation

- Exposures to topical substances

- Medication history

- Smoking or tar use

- Illicit drug history

- Family history of similar findings/concerns

When it comes to the specific complaint, it is important to know the following information:

- How many digits are affected and whether the condition spread or affected all digits at once

- History of trauma to the affected digits

- Any recent stress

- Whether or not all the nails appear similar.

Examination of all 20 nails is recommended. Close inspection of the nail plate, lunula, and proximal, distal, and lateral nail folds is essential. The clinician should make note of any periungual scale, erythema, or other cutaneous findings that might indicate an underlying primary dermatologic disorder. The presence of increased longitudinal or transverse nail curvature and onycholysis should be assessed. Nailfold capillaroscopy should be performed to look for irregularities in the capillaries of the proximal nail folds, which may indicate an autoimmune connective-tissue disorder. Signs of cyanosis or ischemia suggest that circulatory insufficiency may play a role in the nail abnormalities.

Assessment of ridges and longitudinal grooves

- Proposed score for ridging

- 0 = None, clear of any signs of ridging and longitudinal grooves

- 1 = Mild, few plane ridges and longitudinal grooves

- 2 = Moderate, few deep ridges and longitudinal grooves

- 3 = Severe, more than 70% of the nail plate showing deep ridges and corresponding grooves

- Proposed score for longitudinal splitting

- 0 = None, clear of clinical signs of longitudinal nail splitting

- 1 = Mild, one single, superficial longitudinal split of the nail plate

- 2 = Moderate, at least one deep longitudinal split of the entire nail plate

- 3 = Severe, multiple, superficial and deep longitudinal splits of the nail plate.

Laboratory studies

Depending on the clinical severity and pertinent positives on review of systems, it may be important to collect bloodwork to investigate further. In a brittle nail workup, physicians may be inclined to order thyroid studies, an erythrocyte sedimentation rate (marker of acute inflammation), complete blood cell counts, a comprehensive metabolic panel (which includes glucose, electrolytes, and markers of renal and hepatic function), antinuclear antibody titers, and iron (iron deficiency), ferritin, and zinc levels. If onychomycosis is suspected, nail plate and subungual debris samples should be sent for fungal culture, periodic acid-Schiff staining, and/or molecular testing.

Onychoschizia treatment

Onychoschizia treatment involves the correct diagnosis and treating the underlying cause. Nail splitting is generally considered a cosmetic problem, but see your doctor if the condition becomes bothersome.

Treatment of onychoschizia can be difficult, however preventative measures and/or oral supplements can be useful in improving nail strength 5. It has been proposed that onychoschizia is associated with chronic wetting and drying, therefore a suggested management approach may involve hydrating the nail followed by an occlusive topical agent that promotes water retention 4. Preventative measures can also include wearing gloves whilst performing chores that involve getting the hands wet, avoiding regular application of nail polish, or applying nail polishes that contain nylon fibers that may help strengthen soft nails 27. Excessive manipulation of the nail should also be avoided, although shaping and filing the nail can help prevent further breakage or splitting. The vitamin Biotin or vitamin B7 can be used as an oral supplement and has been tested in subjects with onychoschizia 28. A review of clinical trials 29 showed that an improvement in the firmness, hardness, and thickness of brittle nails was seen in subjects treated with oral biotin (vitamin B7). A further trial showed that 91% of subjects had a definite improvement in fingernail hardness after daily biotin treatment for an average of 5.5 months 30. However, larger clinical trials are needed to determine the efficacy and optimal dosing.

Self-care guidelines

- Reduce how often you wet and dry your nails.

- Wear plastic or rubber gloves over thin cotton gloves while doing all housework, including food preparation.

- Keep the nails trimmed short to reduce worsening of nail splitting.

- Soak the nails in water daily, 15 minutes at a time, to increase the water content (hydration) of the nails.

- Apply moisturizers (emollients), such as petroleum jelly or Cetaphil®, to improve nail hydration.

- Nail-hardening agents containing formaldehyde may increase nail strength, but they should be used cautiously, as they can cause brittleness and other nail problems. Apply these hardeners only to the free edge (growing end) of the nail.

- Acrylate-containing hardeners are also effective, but they may cause an allergic reaction in the skin.

Treatments your physician may prescribe

In secondary nail brittleness cases, treatment includes the cure of the dermatological/systemic condition, avoidance of traumas and allergens/irritants, limiting contact with water and detergents, and regular use of emollients 11. However, most patients consulting for nail brittleness have an idiopathic nail fragility. Oral supplementation with vitamins (especially biotin, also known as vitamin B7), trace elements, and amino acids (especially cysteine) have been reported useful in improving idiopathic nail fragility 31. However, these studies were small, not well controlled, and one study was retrospective, survey based.

Biotin or vitamin B7 is a water-soluble vitamin contained in several foods such as cereals, walnuts, peanuts, milk, and egg yolks. Vitamin B7 is also synthetized by intestinal bacteria. Biotin:

Takes part in keratin biosynthesis and intercellular cement holding keratinocytes together, acting as the prosthetic group of several essential enzymes;

Improves the ultrastructure of the nail plate (onychocytes show more regular arrangements and distribution) and its resistance to tension.

Several studies have demonstrated, both with clinical and electron microscopy examinations 32, an improvement of firmness and hardness of the fingernails of patients receiving biotin supplementation 33. A dosage of 5–10 mg a day for 3–6 months is usually recommended.

High biotin intake (more than 10 mg per day) can cause falsely high or falsely low laboratory test results 34. Troponins, thyroid, prolactin and pregnancy tests are some of the most frequently altered 35. The presence of biotin can interfere with tests that use biotin–streptavidin technology. The interaction between biotin and streptavidin is used as the basis for many biotin-based immunoassays, and these immunoassays are vulnerable to interference when they are used to analyze a sample that contains biotin. The FDA warning on this topic emphasizes that physicians should obtain an updated list of medications, including vitamins and supplements, and doses, at each visit 34. This is particularly important as patients are not aware of the risks associated with biotin 36.

A combination of an arginine silicate complex and magnesium biotinate (a novel well-absorbed biotin salt) was demonstrated to increase nail growth 37. However, the studies were small and two of them lacked a control group 38.

Iron supplementation (plus vitamin C) may be very effective when ferritin levels are below 10 ng/ml. However, studies that correlate iron deficit with brittle nails are rarely reported 39.

Primary and secondary zinc deficiency is a cause of nail fragility. Prolonged treatment with zinc 20–30 mg/day seems to be effective in improving brittle nails 39.

In a recent randomized trial, a biomineral formulation containing amino acids (l-cystine, l-arginine, glutamic acid), vitamins (C, E, B6 and biotin) and minerals (zinc, iron and copper) proved to be well tolerated and effective in strengthening and smoothing fingernails in subjects with onychoschizia after 3 months of treatment 40. No data about dosage of the single elements is provided in the article 40.

In an open-label single-center trial, supplementation with “bioactive collagen peptides” was shown to be very effective in patients with brittle nails after 24 weeks of treatment. In this study it was reported that nail growth rate increased by 12% and the frequency of broken nails decreased by 42% 41.

Nail moisturizers are useful in patients with brittle nails. They may contain occlusive material (petrolatum or lanolin) and humectants (glycerin, propylene glycol and proteins). Alpha-hydroxy acids and urea may also be added to increase the water-binding capacity of the nail plate.

Several lacquers are commercially available to restructure nails affected by fragility. These products are known as nail hardeners, nail strengtheners, and fortifying nail builders, and may contain silicon. A new water-soluble nail strengthener specially formulated with a combination of active ingredients (silanediol salicylate and Pistacia lentiscus gum) that increase the quantity and quality of silicon and keratin in the nails. It contains cationic hyaluronic acid that adheres to the surface and deeply moisturizes the nails and cuticles. This combination of ingredients (patent pending) helps the natural process of nail growth. The safety and efficacy are supported by a 6-month clinical study 42.

A recent study observed that hydroxypropyl chitosan nail lacquer when applied on the nails is useful to protect them against physical injuries, improving the nail structure 43. The authors correlate the efficacy of hydroxypropyl chitosan to the high affinity with keratin that is secondary to water solubility without pH correction 43.

A second lacquer composed of 16% polyureaurethane could be used in brittle nails to create a flexible waterproof barrier to environmental hazards 44. The once daily application of both lacquers is recommended.

In a randomized controlled pilot study, the efficacy of topical cyclosporine emulsion versus emulsion (vehicle) alone have been compared. Cyclosporine emulsion and also emulsion alone appeared to improve signs of brittle nails. Limitations of this study were the small sample size and the method for detection of efficacy 45.

These nail lacquers could increase the cosmetic outcomes of brittle nails, but further data are necessary to prove their true efficacy 46.

In recalcitrant fragility, nail wrapping limited to the distal portion of the nail may afford protection and camouflage. The procedure of nail wrapping consists of the application of layers of fibrous substances made of tissue paper, silk, linen, plastic film, or fiberglass on the distal edge of the nail plate to strengthen or repair its free edge. This same method is performed in artificial nails and sculptured nails and can considerably improve brittle nails cosmetically. However, artificial nails could themselves be responsible for fragility because of the materials and procedures used to apply them 47.

Good advice is to wear cotton gloves under vinyl gloves for wet work and heavy cotton gloves for dry work.

- Baran R, Schoon D. Nail fragility syndrome and its treatment. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2004;3(3):131–137. doi:10.1111/j.1473-2130.2004.00076.x[↩]

- Singh G, Haneef NS, Uday A. Nail changes and disorders among the elderly. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2005;71(6):386–392.[↩]

- Paller A, Mancini AJ, Hurwitz S. Hurwitz Clinical Pediatric Dermatology: A Textbook of Skin Disorders of Childhood and Adolescence. 5th ed. New York: Elsevier/Saunders; 2011.[↩][↩]

- Wallis MS, Bowen WR, Guin JD. Pathogenesis of onychoschizia (lamellar dystrophy). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;24(1):44–48. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(91)70007-O[↩][↩]

- Iorizzo M, Pazzaglia M, Piraccini BM, Tullo S, Tosti A. Brittle nails. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2004;3(3):138–144. doi:10.1111/j.1473-2130.2004.00084.x[↩][↩]

- Keohane C, McMullin MF, Harrison C. The diagnosis and management of erythrocytosis. BMJ. 2013;347:f6667. doi:10.1136/bmj.f6667[↩]

- Heldt Manica LA, Cohen PR. Ibrutinib-associated nail plate abnormalities: case reports and review. Drug Saf Case Rep. 2017;4(1):15. doi:10.1007/s40800-017-0060-1[↩]

- Cashman MW, Sloan SB. Nutrition and nail disease. Clin Dermatol. 2010;28(4):420–425. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2010.03.037[↩]

- Chessa MA, Iorizzo M, Richert B, et al. Pathogenesis, Clinical Signs and Treatment Recommendations in Brittle Nails: A Review [published correction appears in Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2020 Jan 22;:]. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2020;10(1):15-27. doi:10.1007/s13555-019-00338-x https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6994568[↩]

- van de Kerkhof PC, Pasch MC, Scher RK, Kerscher M, Gieler U, Haneke E, et al. Brittle nail syndrome: a pathogenesis-based approach with a proposed grading system. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005 Oct. 53 (4):644-51.[↩]

- Brosche T, Dressler A, Platt D. Age-associated changes in integral cholesterol and cholesterol sulfate concentrations in human scalp hair and fingernail clippings. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2001;13:131–138. doi: 10.1007/BF03351535[↩][↩]

- Scher RK, Bodian AB. Brittle nails. Semin Dermatol. 1991;10:21–25.[↩]

- Duarte AF, Correia O, Baran R. Nail plate cohesion seems to be water independent. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:193–195. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2009.03978.x[↩][↩]

- Van de Kerkhof PC, Pasch MC, Scher RK, et al. Brittle nail syndrome: a pathogenesis-based approach with a proposed grading system. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:644–651. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2004.09.002[↩]

- Bardazzi F, Lambertini M, Chessa MA, Magnano M, Patrizi A, Piraccini BM. Nail involvement as a negative prognostic factor in biological therapy for psoriasis: a retrospective study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:843–846. doi: 10.1111/jdv.13979[↩]

- Tosti A, Piraccini BM, Cameli N. Nail changes in lichen planus may resemble those of yellow nail syndrome. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:848–849. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2000.03460.x[↩]

- Chessa MA, Alessandrini A, Starace M, et al. Erosive lichen planus: beyond the nails. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33:e97–e99. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15319[↩]

- Kim M, Jung HY, Eun YS, Cho BK, Park HJ. Nail lichen striatus: report of seven cases and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:1255–1260. doi: 10.1111/ijd.12643[↩]

- Piraccini BM, Balestri R, Starace M, Rech G. Nail digital dermoscopy (onychoscopy) in the diagnosis of onychomycosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:509–513. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2011.04323.x[↩]

- Fustà X, Morgado-Carrasco D, Mascaró JM., Jr Image gallery: nail involvement in syphilis: the great forgotten. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177:e158. doi: 10.1111/bjd.15819[↩]

- Samman PD, Fenton DA. Samman’s the nails in disease. In: 5th ed Oxford. Boston: Butterworth-Heinemann; 1995.[↩]

- Taguchi T. Brittle nails and hair loss in hypothyroidism. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1363. doi: 10.1056/NEJMicm1801633[↩]

- Geyer AS, Onumah N, Uyttendaele H, Scher RK. Modulation of linear nail growth to treat diseases of the nail. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:229–234. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2003.07.011[↩]

- Batory M, Namieciński P, Rotsztejn H. Evaluation of structural damage and pH of nail plates of hands after applying different methods of decorating. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:311–318. doi: 10.1111/ijd.14198[↩]

- Zaias N. The nail in health and disease. 2nd edn. Mc graw Hill Professional, 1992.[↩]

- Weistenhöfer W, Uter W, Drexler H. Protection during production: problems due to prevention? Nail and skin condition after prolonged wearing of occlusive gloves. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2017;80:396–404. doi: 10.1080/10937404.2017.1304741[↩]

- Paller A, Mancini AJ, Hurwitz S. Hurwitz Clinical Pediatric Dermatology: A Textbook of Skin Disorders of Childhood and Adolescence. 5th ed. New York: Elsevier/Saunders; 2011. [↩]

- Colombo VE, Gerber F, Bronhofer M, Floersheim GL. Treatment of brittle fingernails and onychoschizia with biotin: scanning electron microscopy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;23(6 Pt 1):1127–1132. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(90)70345-I[↩]

- Lipner SR, Scher RK. Biotin for the treatment of nail disease: what is the evidence? J Dermatolog Treat. 2018;29(4):411–414. doi:10.1080/09546634.2017.1395799[↩]

- Floersheim GL. [Treatment of brittle fingernails with biotin]. Z Hautkr. 1989;64(1):41–48.[↩]

- Almohanna HM, Ahmed AA, Tsatalis JP, Tosti A. The role of vitamins and minerals in hair loss: a review. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2019;9:51–70. doi: 10.1007/s13555-018-0278-6[↩]

- Kitamori K, Kobayashi M, Akamatsu H, et al. Weakness in intercellular association of keratinocytes in severely brittle nails. Arch Histol Cytol. 2006;69:323–328. doi: 10.1679/aohc.69.323[↩]

- Hochman LG, Scher RK, Meyerson MS. Brittle nails: response to daily biotin supplementation. Cutis. 1993;51:303–305.[↩]

- Administration USFaD. Biotin (vitamin B7): Safety communication – may interfere 154 with lab tests. In: 11/28/2017, ed.[↩][↩]

- Maddy AJ, Tosti A. What’s new in nail disorders. Dermatol Clin. 2019;37:143–147. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2018.12.004[↩]

- John JJ, Cooley V, Lipner SR. Assessment of biotin supplementation among patients in an outpatient dermatology clinic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:620–621. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.12.045[↩]

- James K, Sara PO, Sarah S et al. The effect of a combination of an arginine silicate complex and magnesium biotinate on hair and nail growth in rats (P06-026-19). Curr Dev Nutr. 2019;3:nzz031.P06-026-19[↩]

- Lipner SR, Scher RK. Biotin for the treatment of nail disease: what is the evidence? J Dermatol Treat. 2018;29:411–414. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2017.1395799[↩]

- Di Baise M, Tarleton SM. Hair, nails, and skin: differentiating cutaneous manifestations of micronutrient deficiency. Nutr Clin Pract. 2019;34:490–503. doi: 10.1002/ncp.10321[↩][↩]

- Sparavigna A, Tenconi B, La Penna L. Efficacy and tolerability of a biomineral formulation for treatment of onychoschizia: a randomized trial. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2019;13(12):355–362. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S187305[↩][↩]

- Hexsel D, Zague V, Schunck M, Siega C, Camozzato FO, Oesser S. Oral supplementation with specific bioactive collagen peptides improves nail growth and reduces symptoms of brittle nails. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2017;16:520–526. doi: 10.1111/jocd.12393[↩]

- Starace M, Alessandrini A, Bruni F, Brandi N, Piraccini BM. An open clinical investigation on clinically and dermoscopically visible effects of application of a topical product for 6 months on brittle nails and weak nails with rough surface and/or tendency to break. Poster presented at the 24th Word Congress of Dermatology, Milan, 10–15 June 2019.[↩]

- Sparavigna A, Caserini M, Tenconi B, et al. Effects of a novel nail lacquer based on hydroxypropyl-chitosan (HPCH) in subjects with fingernail onychoschizia. J Dermatol Clin Res. 2014;2:1013–1018.[↩][↩]

- Iorizzo M. Tips to treat the 5 most common nail disorders: brittle nails, onycholysis, paronychia, psoriasis, onychomycosis. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:175–183. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2014.12.001[↩]

- Mackay-Wiggan J, Marji J, Walt JG, et al. Topical cyclosporine versus emulsion vehicle for the treatment of brittle nails: a randomized controlled pilot study. J Drugs Dermatol. 2014;13:1232–1239.[↩]

- Iorizzo M, Piraccini BM, Tosti A. Nail cosmetics in nail disorders. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2007;6:53–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1473-2165.2007.00290.x[↩]

- Dahdah MJ, Scher RK. Nail diseases related to nail cosmetics. Dermatol Clin. 2006;24(233–9):vii.[↩]