Oral rehydration therapy

Oral rehydration therapy also called ORT, oral rehydration salts, oral rehydration solutions (ORS) or oral electrolyte solution, is a simple, cheap and effective treatment for diarrhea-related dehydration, for example due to cholera or rotavirus. Oral rehydration therapy consists of a solution of salts and other substances such as glucose, sucrose, citrates or molasses, which is administered orally. Oral rehydration therapy (ORT) includes rehydration and maintenance fluids with oral rehydration solutions (ORS), combined with continued age-appropriate nutrition 1. Oral rehydration therapy is used around the world, but is most important in the Third World, where it saves millions of children from diarrhea where it is still the leading cause of death. Oral rehydration therapy has now become the mainstay of the World Health Organization’s (WHO) efforts to decrease diarrhea morbidity and mortality, and Diarrheal Disease Control Programs have been established in more than 100 countries worldwide 2.

Oral rehydration therapy (ORT) encompasses two phases of treatment:

- The rehydration phase, in which water and electrolytes are given as oral rehydration solution (ORS) to replace existing losses, and

- The maintenance phase, which includes both replacement of ongoing fluid and electrolyte losses and adequate dietary intake 3.

It is important to emphasize that although oral rehydration therapy (ORT) implies rehydration alone, in view of present advances, knowledge, and practice, the definition has been broadened to include maintenance fluid therapy and nutrition. Oral rehydration therapy is widely considered to be the best method for combating the dehydration caused by diarrhea and/or vomiting.

Human survival depends on the secretion and reabsorption of fluid and electrolytes in the intestinal tract. The adult intestinal epithelium must handle 6,500 mL of fluids/day, consisting of a combination of oral intake, salivary, gastric, pancreatic, biliary, and upper intestinal secretions. This volume is typically reduced to 1,500 mL by the distal ileum and is further reduced in the colon to a stool output of <250 mL/day in adults 4. During diarrheal disease, the volume of intestinal fluid output is substantially increased, overwhelming the reabsorptive capacity of the gastrointestinal tract.

In the human body, water is absorbed and secreted passively; it follows the movement of salts, based on a principle called osmosis. So, in many cases, diarrhea is caused by intestine cells secreting salts (primarily sodium) and water following passively along. Simply drinking water is ineffective for 2 reasons: (1) the large intestine is usually secreting instead of absorbing water, and (2) electrolyte losses also need compensating. As such, the standard treatment is to restore fluids intravenously with water and salts. This requires trained personnel and materials which are not sufficiently available in the Third World.

However, it was discovered that the body can absorb a simple solution containing both sugar and salt. The dry ingredients can be mixed and packaged, and then the solution can be prepared and delivered by people with minimal training. One diarrhea mechanism (like in cholera, which is a very dangerous form of profuse diarrhea), is an enterotoxin interfering with enterocyte cAMP and G-proteins 5. Rotavirus damages the villous brush border, causing osmotic diarrhea, and also produces an enterotoxin that causes a Ca++-mediated secretory diarrhea 6. However, water can still be absorbed by cAMP-independent mechanisms, like the SGLT-transporter (sodium and glucose transporter, of which two types exist). This is achieved by combining salts and glucose.

Oral rehydration therapy can be accomplished by drinking frequent small amounts of an oral rehydration salt solution.

It is important to rehydrate with solutions that contain electrolytes, especially sodium and potassium, so that electrolyte disturbances may be avoided. Sugar is absolutely essential to improve adequate absorption of electrolytes and water, but the presence of sugar in oral rehydration solutions (ORS) does tend to cause diarrhea to worsen. Although oral rehydration with a sugar solution does not stop diarrhea, and the diarrhea contributes to further loss of fluids, oral rehydration solutions (ORS) helps replace these fluids. It thus keeps the body hydrated and gives the patient a greatly improved chance of surviving the diarrhea. If a broth can be prepared from simple carbohydrates and substituted for sugar in the solution, diarrhea can sometimes be reduced while oral rehydration solutions (ORS) remains effective. Often sodium bicarbonate or sodium citrate is also added to formulas in an attempt to revert metabolic acidosis.

Oral rehydration solution (ORS) is a sodium and glucose solution which is prepared by diluting 1 sachet of oral rehydration salts in 1 liter of safe water. It is important to administer the oral rehydration solution (ORS) in small amounts at regular intervals on a continuous basis. In case oral rehydration salts packets are not available, homemade solutions consisting of either half a small spoon of salt and six level small spoons of sugar dissolved in one liter of safe water, or lightly salted rice water or even plain water may be given to PREVENT or DELAY the onset of dehydration on the way to the health facility 7. However, these solutions are inadequate for TREATING dehydration caused by acute diarrhea, particularly cholera, in which the stool loss and risk of shock are often high. To avoid dehydration, increased fluids should be given as soon as possible. All oral fluids, including oral rehydration solutions (ORS), should be prepared with the best available drinking water and stored safely. Continuous provision of nutritious food is essential and breastfeeding of infants and young children should continue 7.

If you suspect gastroenteritis in yourself:

- Sip liquids, such as a sports drink or water, to prevent dehydration. Drinking fluids too quickly can worsen the nausea and vomiting, so try to take small frequent sips over a couple of hours, instead of drinking a large amount at once.

- Take note of urination. You should be urinating at regular intervals, and your urine should be light and clear. Infrequent passage of dark urine is a sign of dehydration. Dizziness and lightheadedness also are signs of dehydration. If any of these signs and symptoms occur and you can’t drink enough fluids, seek medical attention.

- Ease back into eating. Try to eat small amounts of food frequently if you experience nausea. Otherwise, gradually begin to eat bland, easy-to-digest foods, such as soda crackers, toast, gelatin, bananas, applesauce, rice and chicken. Stop eating if your nausea returns. Avoid milk and dairy products, caffeine, alcohol, nicotine, and fatty or highly seasoned foods for a few days.

- Get plenty of rest. The illness and dehydration can make you weak and tired.

- Diarrhea usually stops in three or four days. If it does not stop, consult a trained health professional.

If you suspect gastroenteritis in your child:

- Allow your child to rest.

- When your child’s vomiting stops, begin to offer small amounts of an oral rehydration solution (CeraLyte, Enfalyte, Pedialyte). Don’t use only water or only apple juice. Drinking fluids too quickly can worsen the nausea and vomiting, so try to give small frequent sips over a couple of hours, instead of drinking a large amount at once. Try using a water dropper of rehydration solution instead of a bottle or cup.

- Gradually introduce bland, easy-to-digest foods, such as toast, rice, bananas and potatoes. Avoid giving your child full-fat dairy products, such as whole milk and ice cream, and sugary foods, such as sodas and candy. These can make diarrhea worse.

- If you’re breast-feeding, let your baby nurse. If your baby is bottle-fed, offer a small amount of an oral rehydration solution or regular formula.

Things you should know about rehydrating your child:

- Wash your hands with soap and water before preparing solution.

- Prepare a oral rehydration solution (ORS), in a clean pot, by mixing – Six (6) level teaspoons of sugar and Half (1/2) level teaspoon of Salt

or 1 packet of Oral Rehydration Salts 20.5 grams mix with one litre of clean drinking or boiled water (after cooled). Stir the mixture till all the contents dissolve. - Wash your hands and the baby’s hands with soap and water before feeding solution.

- Give the sick child as much of the solution as it needs, in small amounts frequently.

- Give child alternately other fluids – such as breast milk and juices.

- Continue to give solids if child is four months or older.

- If the child still needs oral rehydration solution (ORS) after 24 hours, make a fresh solution.

- Oral rehydration solution (ORS) does not stop diarrhea. It prevents the body from drying up. The diarrhea will stop by itself.

- If child vomits, wait ten minutes and give it oral rehydration solution (ORS) again. Usually vomiting will stop.

- If diarrhea increases and /or vomiting persists, take child over to a health clinic.

Seek medical attention if:

- Vomiting persists more than two days

- Diarrhea persists more than several days

- Diarrhea turns bloody

- Fever is more than 102 °F (39 °C) or higher

- Lightheadedness or fainting occurs with standing

- Confusion develops

- Worrisome abdominal pain develops

Seek medical attention if your child:

- Becomes unusually drowsy.

- Vomits frequently or vomits blood.

- Has bloody diarrhea.

- Shows signs of dehydration, such as dry mouth and skin, marked thirst, sunken eyes, or crying without tears. In an infant, be alert to the soft spot on the top of the head becoming sunken and to diapers that remain dry for more than three hours.

- Is an infant and has a fever.

- Is older than three months of age and has a fever of 102 °F (39 °C) or more.

What is oral rehydration salts?

Oral rehydration salts is a special combination of dry salts that is mixed with safe water. It can help replace the fluids lost due to diarrhea.

Where can oral rehydration salts be obtained?

In most countries, oral rehydration salts packets are available from health centers, pharmacies, markets and shops.

How is the oral rehydration salts drink prepared?

- Put the contents of the oral rehydration salts packet in a clean container. Check the packet for directions and add the correct amount of clean water. Too little water could make the diarrhea worse.

- Add water only. Do not add oral rehydration salts to milk, soup, fruit juice or soft drinks. Do not add sugar.

- Stir well, and feed it to the child from a clean cup. Do not use a bottle.

What if oral rehydration salts is not available?

Give the child a drink made with 6 level teaspoons of sugar and 1/2 level teaspoon of salt dissolved in 1 liter of clean water.

Be very careful to mix the correct amounts. Too much sugar can make the diarrhea worse. Too much salt can be extremely harmful to the child.

Making the mixture a little too diluted (with more than 1 liter of clean water) is not harmful.

When should oral rehydration solution be used?

When a child has three or more loose stools in a day, begin to give oral rehydration solution (ORS). In addition, for 10–14 days, give children over 6 months of age 20 milligrams of zinc per day (tablet or syrup); give children under 6 months of age 10 milligrams per day (tablet or syrup).

How much oral rehydration solution do I feed?

Encourage the child to drink as much as possible and feed after every loose motion. Adults and large children should drink at least 3 quarts or liters of Oral Rehydration Solutions (ORS) a day until they are well.

Each Feeding:

- For a child under the age of two: A child under the age of 2 years needs at least 1/4 to 1/2 of a large (250-milliliter) cup of the oral rehydration solution (ORS) drink after each watery stool.

- For older children: A child aged 2 years or older needs at least 1/2 to 1 whole large (250-milliliter) cup of the oral rehydration solution (ORS) drink after each watery stool.

For Severe Dehydration:

Drink sips of the Oral Rehydration Solutions (ORS) (or give the ORS solution to the conscious dehydrated person) every 5 minutes until urination becomes normal. It’s normal to urinate four or five times a day.

How do I feed the solution?

- Give it slowly, preferably with a teaspoon.

- If the child vomits it, give it again.

The drink should be given from a cup (feeding bottles are difficult to clean properly). Remember to feed sips of the liquid slowly.

What if the child vomits?

If the child vomits, wait for ten minutes and then begin again. Continue to try to feed the drink to the child slowly, small sips at a time. The body will retain some of the fluids and salts needed even though there is vomiting.

For how long do I feed the liquids?

Extra liquids should be given until the diarrhea has stopped. This will usually take between three and five days.

How do I store the oral rehydration solution?

Store the liquid in a cool place. Chilling the Oral Rehydration Solutions (ORS) may help. If the child still needs ORS after 24 hours, make a fresh solution.

How to make Oral Rehydration Solutions

Home made Oral Rehydration Solutions Recipe

Preparing 1 (one) Liter solution using Salt, Sugar and Water at Home.

Mix an oral rehydration solution using the following recipe. Ingredients:

- Six (6) level teaspoons of Sugar (molasses and other forms of raw sugar can be used instead of white sugar, and these contain more potassium than white sugar)

- Half (1/2) level teaspoon of Salt

- One Liter of clean drinking or boiled water and then cooled – 5 cupfuls (each cup about 200 ml.)

Preparation Method:

- Stir the mixture till the salt and sugar dissolve.

- If possible, add 1/2 cup orange juice or some mashed banana to improve the taste and provide some potassium.

NOTE: Do not use too much salt. If the solution has too much salt the child may refuse to drink it. Also, too much salt can, in extreme cases, cause convulsions. Too little salt does no harm but is less effective in preventing dehydration. A rough guide to the amount of salt is that the solution should taste no saltier than tears.

A good substitute for oral rehydration solutions (ORS)

- Ingredients:

- 1/2 to 1 cup precooked baby rice cereal or 1½ tablespoons of granulated sugar

- 2 cups of water

- 1/2 tsp. salt

- Instructions:

- Mix well the rice cereal (or sugar), water, and salt together until the mixture thickens but is not too thick to drink. Give the mixture often by spoon and offer the child as much as he or she will accept (every minute if the child will take it). Continue giving the mixture with the goal of replacing the fluid lost: one cup lost, give a cup. Even if the child is vomiting, the mixture can be offered in small amounts (1-2 tsp.) every few minutes or so.

- Banana or other non-sweetened mashed fruit can help provide potassium.

- Continue feeding children when they are sick and to continue breastfeeding if the child is being breastfed.

- Mix well the rice cereal (or sugar), water, and salt together until the mixture thickens but is not too thick to drink. Give the mixture often by spoon and offer the child as much as he or she will accept (every minute if the child will take it). Continue giving the mixture with the goal of replacing the fluid lost: one cup lost, give a cup. Even if the child is vomiting, the mixture can be offered in small amounts (1-2 tsp.) every few minutes or so.

The following traditional remedies also make highly effective oral rehydration solutions (ORS) and are suitable drinks to prevent a child from losing too much liquid during diarrhea:

- Breastmilk

- Gruels (diluted mixtures of cooked cereals and water)

- Carrot Soup

- Rice water – Congee

If none of these drinks is available, other alternatives are:

- Fresh fruit juice

- Weak tea

- Green coconut water

If nothing else is available, give:

- water from the cleanest possible source (if possible brought to the boil and then cooled).

Acute gastroenteritis therapy based on degree of dehydration

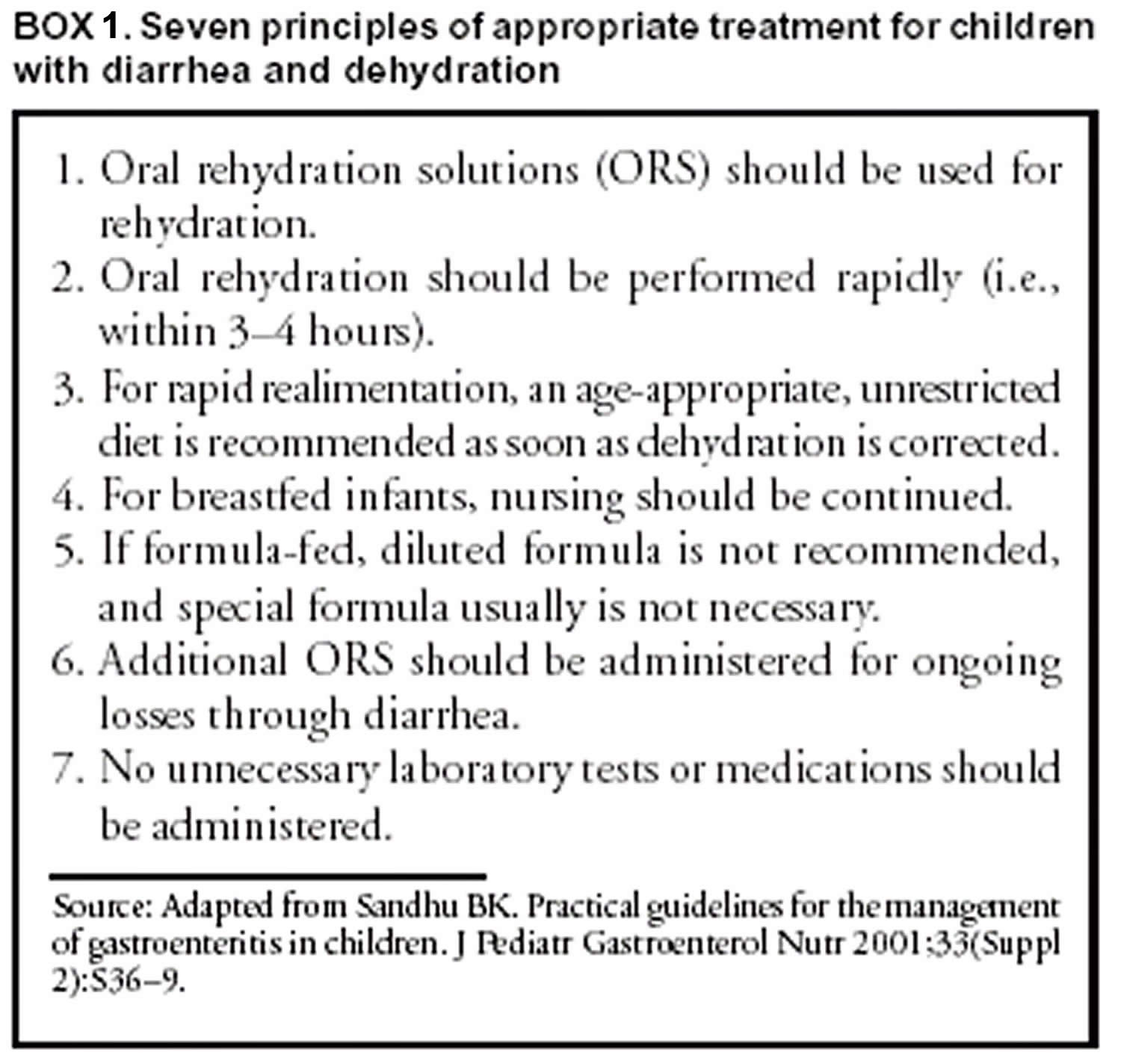

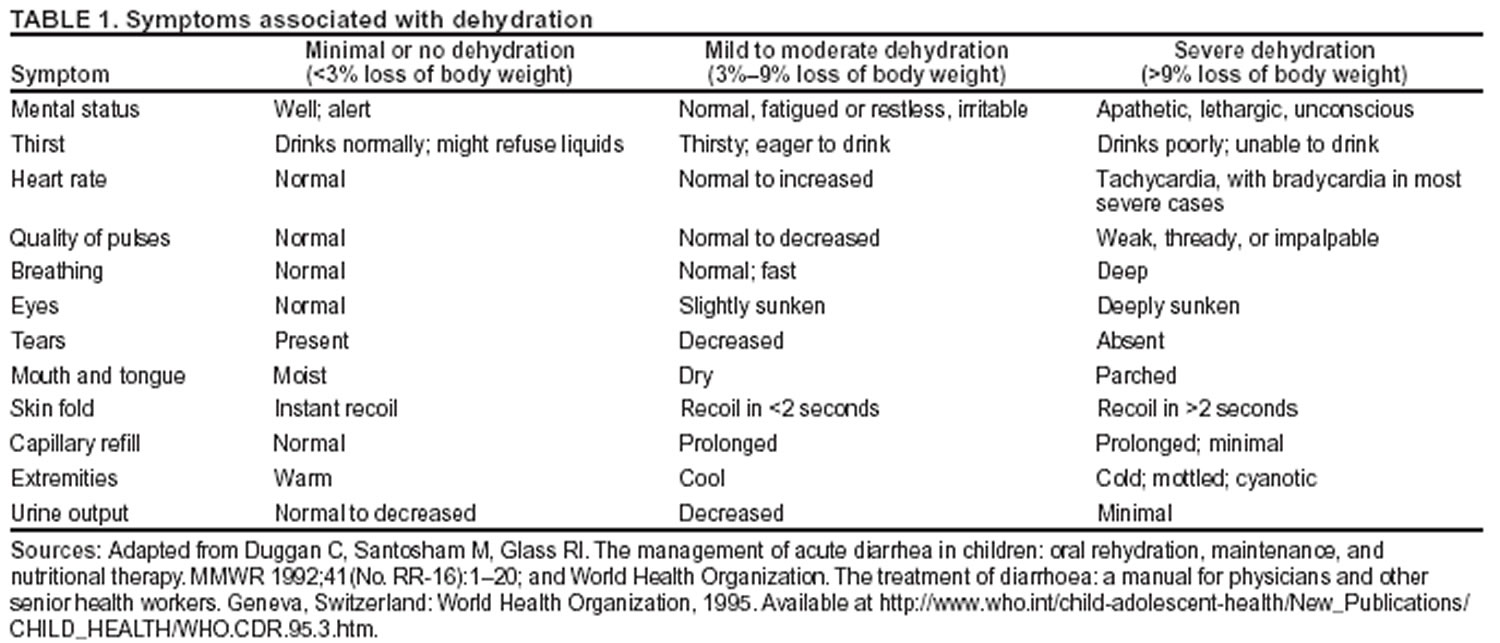

Seven basic principles guide optimal treatment of acute gastroenteritis (Box 1) 8; more specific recommendations for treating different degrees of dehydration have been recommended by the Centers for Disease Prevention and Control (CDC), World Health Organization (WHO), and the American Academy of Pediatrics (Table 1) 9. Treatment should include two phases: rehydration and maintenance. In the rehydration phase, the fluid deficit is replaced quickly (i.e., during 3–4 hours) and clinical hydration is attained. In the maintenance phase, maintenance calories and fluids are administered. Rapid realimentation should follow rapid rehydration, with a goal of quickly returning the patient to an age-appropriate unrestricted diet, including solids. Gut rest is not indicated. Breastfeeding should be continued at all times, even during the initial rehydration phases. The diet should be increased as soon as tolerated to compensate for lost caloric intake during the acute illness. Lactose restriction is usually not necessary (although it might be helpful in cases of diarrhea among malnourished children or among children with a severe enteropathy), and changes in formula usually are unnecessary. Full-strength formula usually is tolerated and allows for a more rapid return to full energy intake. During both phases, fluid losses from vomiting and diarrhea are replaced in an ongoing manner. Antidiarrheal medications are not recommended for infants and children, and laboratory studies should be limited to those needed to guide clinical management.

Minimal dehydration

For patients with minimal or no dehydration, treatment is aimed at providing adequate fluids and continuing an age-appropriate diet. Patients with diarrhea must have increased fluid intake to compensate for losses and cover maintenance needs; use of oral rehydration solutions (ORS) should be encouraged. In principle, 1 mL of fluid should be administered for each gram of output. In hospital settings, soiled diapers can be weighed (without urine), and the estimated dry weight of the diaper can be subtracted. When losses are not easily measured, 10 mL of additional fluid can be administered per kilogram body weight for each watery stool or 2 mL/kg body weight for each episode of emesis. As an alternative, children weighing <10 kg should be administered 60–120 mL (2–4 ounces) oral rehydration solution (ORS) for each episode of vomiting or diarrheal stool, and those weighing >10 kg should be administered 120–240 mL (4–8 ounces). Nutrition should not be restricted (see Dietary Therapy).

Mild to Moderate Dehydration

Children with mild to moderate dehydration should have their estimated fluid deficit rapidly replaced. These updated recommendations include administering 50–100 mL of oral rehydration solution (ORS)/kg body weight during 2–4 hours to replace the estimated fluid deficit, with additional ORS administered to replace ongoing losses. Using a teaspoon, syringe, or medicine dropper, limited volumes of fluid (e.g., 5 mL or 1 teaspoon) should be offered at first, with the amount gradually increased as tolerated. If a child appears to want more than the estimated amount of ORS, more can be offered. Although administering ORS rapidly is safe, vomiting might be increased with larger amounts. Nasogastric (NG) feeding allows continuous administration of ORS at a slow, steady rate for patients with persistent vomiting or oral ulcers. Clinical trials support using nasogastric feedings, even for vomiting patients 10. Rehydration through an NG tube can be particularly useful in emergency department settings, where rapid correction of hydration might prevent hospitalization. Although rapid IV hydration can also prevent hospital admission, rapid nasogastric rehydration can be well-tolerated, more cost-effective, and associated with fewer complications 10. In addition, a randomized trial of ORS versus IV rehydration for dehydrated children demonstrated shorter stays in emergency departments and improved parental satisfaction with oral rehydration 11.

Certain children with mild to moderate dehydration will not improve with ORT; therefore, they should be observed until signs of dehydration subside. Similarly, children who do not demonstrate clinical signs of dehydration but who demonstrate unusually high output should be held for observation. Hydration status should be reassessed on a regular basis, and might be performed in an emergency department, office, or other outpatient setting. After dehydration is corrected, further management can be implemented at home, provided that the child’s caregivers demonstrate comprehension of home rehydration techniques (including continued feeding), understand indications for returning for further evaluation, and have the means to do so. Even among children whose illness appears uncomplicated on initial assessment, a limited percentage might not respond adequately to ORT; therefore, a plan for reassessment should be agreed upon. Caregivers should be encouraged to return for medical attention if they have any concerns, if they are not sure that rehydration is proceeding well, or if new or worsening symptoms develop.

Severe dehydration

Severe dehydration constitutes a medical emergency requiring immediate IV rehydration. Lactated Ringer’s solution, normal saline, or a similar solution should be administered (20 mL/kg body weight) until pulse, perfusion, and mental status return to normal. This might require two IV lines or even alternative access sites (e.g., intraosseous infusion). The patient should be observed closely during this period, and vital signs should be monitored on a regular basis. Serum electrolytes, bicarbonate, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, and serum glucose levels should be obtained, although commencing rehydration therapy without these results is safe. Normal saline or Lactated Ringer’s infusion is the appropriate first step in the treatment of hyponatremic and hypernatremic dehydration. Hypotonic solutions should not be used for acute parenteral rehydration 12.

Severely dehydrated patients might require multiple administrations of fluid in short succession. Overly rapid rehydration is unlikely to occur as long as weight-based amounts are administered with close observation. Errors occur most commonly in settings where adult dosing is administered to infants (e.g., “500 mL normal saline IV bolus x 2” would provide 200 mL/kg body weight for an average infant aged 2–3 months). Edema of the eyelids and extremities can indicate overhydration. Diuretics should not be administered. After the edema has subsided, the patient should be reassessed for continued therapy. With frail or malnourished infants, smaller amounts (10 mL/kg body weight) are recommended because of the reduced ability of these infants to increase cardiac output and because distinguishing dehydration from sepsis might be difficult among these patients. Smaller amounts also will facilitate closer evaluation. Hydration status should be reassessed frequently to determine the adequacy of replacement therapy. A lack of response to fluid administration should raise the suspicion of alternative or concurrent diagnoses, including septic shock and metabolic, cardiac, or neurologic disorders.

As soon as the severely dehydrated patient’s level of consciousness returns to normal, therapy usually can be changed to the oral route, with the patient taking by mouth the remaining estimated deficit. An nasogastric tube can be helpful for patients with normal mental status but who are too weak to drink adequately. Although no studies have specifically documented increased aspiration risk with nasogastric tube use in obtunded patients, IV therapy is typically favored for such patients. Although leaving IV access in place for these patients is reasonable in case it is needed again, early reintroduction of ORS is safer. Using IV catheters is associated with frequent minor complications, including extravasation of IV fluid, and with rare substantial complications, including the inadvertent administration of inappropriate fluid (e.g., solutions containing excessive potassium). In addition, early oral rehydration solution (ORS) will probably encourage earlier resumption of feeding, and data indicate that resolution of acidosis might be more rapid with ORS than with IV fluid 10.

Dietary therapy

Recommendations for maintenance dietary therapy depend on the age and diet history of the patient. Breastfed infants should continue nursing on demand. Formula-fed infants should continue their usual formula immediately upon rehydration in amounts sufficient to satisfy energy and nutrient requirements. Lactose-free or lactose-reduced formulas usually are unnecessary. A meta-analysis of clinical trials indicates no advantage of lactose-free formulas over lactose-containing formulas for the majority of infants, although certain infants with malnutrition or severe dehydration recover more quickly when given lactose-free formula 13. Patients with true lactose intolerance will have exacerbation of diarrhea when a lactose-containing formula is introduced. The presence of low pH (<6.0) or reducing substances (>0.5%) in the stool is not diagnostic of lactose intolerance in the absence of clinical symptoms. Although medical practice has often favored beginning feedings with diluted (e.g., half- or quarter-strength) formula, controlled clinical trials have demonstrated that this practice is unnecessary and is associated with prolonged symptoms 14 and delayed nutritional recovery 15.

Formulas containing soy fiber have been marketed to physicians and consumers in the United States, and added soy fiber has been reported to reduce liquid stools without changing overall stool output 16. This cosmetic effect might have certain benefits with regard to diminishing diaper rash and encouraging early resumption of normal diet but is probably not sufficient to merit its use as a standard of care. A reduction in the duration of antibiotic-associated diarrhea has been demonstrated among older infants and toddlers fed formula with added soy fiber 17.

Children receiving semisolid or solid foods should continue to receive their usual diet during episodes of diarrhea. Foods high in simple sugars should be avoided because the osmotic load might worsen diarrhea; therefore, substantial amounts of carbonated soft drinks, juice, gelatin desserts, and other highly sugared liquids should be avoided. Certain guidelines have recommended avoiding fatty foods, but maintaining adequate calories without fat is difficult, and fat might have a beneficial effect of reducing intestinal motility. The practice of withholding food for >24 hours is inappropriate. Early feeding decreases changes in intestinal permeability caused by infection 18, reduces illness duration, and improves nutritional outcomes 19. Highly specific diets (e.g., the BRAT [bananas, rice, applesauce, and toast] diet) have been commonly recommended. Although certain benefits might exist from green bananas and pectin in persistent diarrhea 20, the BRAT [bananas, rice, applesauce, and toast] diet is unnecessarily restrictive and, similar to juice-centered diets, can provide suboptimal nutrition for the patient’s nourishment and recovering gut. Severe malnutrition can occur after gastroenteritis if prolonged gut rest or clear fluids are prescribed 21.

Children in underdeveloped countries often have multiple episodes of diarrhea in a single season, making diarrhea a contributing factor to suboptimal nutrition, which can increase the frequency and severity of subsequent episodes 22. For this reason, increased nutrient intake should be administered after an episode of diarrhea. Recommended foods include age-appropriate unrestricted diets, including complex carbohydrates, meats, yogurt, fruits, and vegetables. Children should as best as possible maintain caloric intake during acute episodes, and subsequently should receive additional nutrition to compensate for any shortfalls arising during the illness.

Supplemental Zinc therapy

Multiple reports have linked diarrhea and abnormal zinc status 23, including increased stool zinc loss, negative zinc balance 24, and reduced tissue levels of zinc 25. Although severe zinc deficiency (e.g., acrodermatitis enteropathica) is associated with diarrhea, milder deficiencies of zinc might play a role in childhood diarrhea, and zinc supplementation might be of benefit either for improved outcomes in acute or chronic diarrhea or as prophylaxis against diarrheal disease. Reduced duration of acute diarrhea after zinc supplementation among patients with low zinc concentrations in rectal biopsies has been demonstrated 25. In Bangladesh, zinc supplements also improved markers of intestinal permeability among children with diarrhea 26. In India, zinc supplementation was associated with a decrease in both the mean number of watery stools per day and the number of days with watery diarrhea 27. Prophylactic zinc supplementation in India has been associated with a substantially reduced incidence of severe and prolonged diarrhea, two key determinants of malnutrition and diarrhea-related mortality 28. In Nepal, this effect was independent of concomitant vitamin A administration, with limited side effects apart from a slight increase in emesis 29. In Peru, zinc administration was associated with a reduction in duration of persistent diarrhea 30. In two different pooled analyses of randomized controlled trials in developing countries (85,86), zinc supplementation was beneficial for treating children with acute and persistent diarrhea and as a prophylactic supplement for decreasing the incidence of diarrheal disease and pneumonia. Among infants and young children who received supplemental zinc for 5 or 7 days/week for 12–54 weeks, the pooled odds ratio for diarrhea incidence was 0.82 and the odds ratio for pneumonia incidence was 0.59. The efficacy and safety of a zinc-fortified (40 mg/L) ORS among 1,219 children with acute diarrhea was evaluated 31. Compared with zinc syrup administered at a dose of 15–30 mg/day, zinc-fortified ORS did not increase the plasma zinc concentration. However, clinical outcomes among the zinc-fortified ORS group were modestly improved, compared with those for the control group, who received standard ORS only. In that study, the total number of stools was lower among the zinc-ORS group (relative risk: 0.83), compared with the total number for the control group. No substantial effect on duration of diarrhea or risk for prolonged diarrhea was noted.

Thus, a number of trials have supported zinc supplementation as an effective agent in treating and preventing diarrheal disease. Further research is needed to identify the mechanism of action of zinc and to determine its optimal delivery to the neediest populations. The role of zinc supplements in developed countries needs further evaluation.

Limitations of oral rehydration therapy

Although oral rehydration therapy (ORT) is recommended for all age groups and for diarrhea of any etiology, certain restrictions apply to its use. Among children in hemodynamic shock, administration of oral solutions might be contraindicated because airway protective reflexes might be impaired. Likewise, patients with abdominal ileus should not be administered oral fluids until bowel sounds are audible. Intestinal intussusception can be present with diarrhea, including bloody diarrhea. Radiographic and surgical evaluation are warranted when the diagnosis of bowel obstruction is in question.

Stool output in excess of 10 mL/kg body weight/hour has been associated with a lower rate of success of oral rehydration 32; however, children should not be denied ORT simply because of a high purging rate, because the majority of children will respond well if administered adequate replacement fluid.

A limited percentage of infants (<1%) with acute diarrhea experience carbohydrate malabsorption. This is characterized by a dramatic increase in stool output after intake of fluids containing simple sugars (e.g., glucose), including oral rehydration solution (ORS). Patients with true glucose malabsorption also will have an immediate reduction in stool output when IV therapy is used instead of ORS. However, the presence of stool-reducing substances alone is not sufficient to make this diagnosis, because this is a common finding among patients with diarrhea and does not in itself predict failure of oral therapy.

Certain patients with acute diarrhea have concomitant vomiting. However, the majority can be rehydrated successfully with oral fluids if limited volumes of oral rehydration solution (ORS) (5 mL) are administered every 5 minutes, with a gradual increase in the amount consumed. Administration with a spoon or syringe under close supervision helps guarantee a gradual progression in the amount taken. Often, correction of acidosis and dehydration lessens the frequency of vomiting. Continuous slow nasogastic infusion of ORS through a feeding tube might be helpful. Even if a limited amount of emesis occurs after nasogastic administration of fluid, treatment might not be affected adversely 10. The physician might meet resistance in implementing nasogastic rehydration in a vomiting child, but nasogastic rehydration might help the initial rehydration and speed up tolerance to refeeding 33, leading to improved patient disposition and quicker discharge.

- Managing Acute Gastroenteritis Among Children. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5216a1.htm[↩]

- The Management of Acute Diarrhea in Children: Oral Rehydration, Maintenance, and Nutritional Therapy. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/00018677.htm[↩]

- Nalin DR. Nutritional benefits related to oral therapy: an overview. In: Bellanti JA, ed. Acute diarrhea: its nutritional consequences in children. Nestle Nutrition Workshop Series, Vol. 2. New York, NY: Raven Press, 1983:185-90.[↩]

- Acra SA, Ghishan GK. Electrolyte fluxes in the gut and oral rehydration solutions. Pediatr Clin North Am 1996;43:433–49.[↩]

- Acheson DW. Enterotoxins in acute infective diarrhoea. J Infect 1992;24:225–45.[↩]

- Ball JM, Tian P, Zeng CQ, Morris AP, Estes MK. Age-dependent diarrhea induced by a rotaviral nonstructural glycoprotein. Science 1996;272:101–4.[↩]

- WHO position paper on Oral Rehydration Salts to reduce mortality from cholera. https://www.who.int/cholera/technical/en/[↩][↩]

- Sandhu BK. Practical guidelines for the management of gastroenteritis in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2001;33(Suppl 2):S36–9.[↩]

- Duggan C, Santosham M, Glass RI. The management of acute diarrhea in children: oral rehydration, maintenance, and nutritional therapy. MMWR 1992;41(No. RR-16):1–20. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/00018677.htm[↩]

- Nager AL, Wang VJ. Comparison of nasogastric and intravenous methods of rehydration in pediatric patients with acute dehydration. Pediatrics 2002;109:566–72.[↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Atherly-John YC, Cunningham SJ, Crain EF. A randomized trial of oral vs intravenous rehydration in a pediatric emergency department. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2002;156:1240–3.[↩]

- Jackson J, Bolte RG. Risks of intravenous administration of hypotonic fluids for pediatric patients in ED and prehospital settings: let’s remove the handle from the pump. Am J Emerg Med 2000;18:269–70.[↩]

- Brown KH, Peerson J, Fontaine O. Use of nonhuman milks in the dietary management of young children with acute diarrhea: a meta-analysis of clinical trials. Pediatrics 1994;93:17–27.[↩]

- Santosham M, Foster S, Reid R, et al. Role of soy-based, lactose-free formula during treatment of acute diarrhea. Pediatrics 1985;76:292–8.[↩]

- Brown KH, Gastanaduy AS, Saavedra JM, et al. Effect of continued oral feeding on clinical and nutritional outcomes of acute diarrhea in children. J Pediatr 1988;112:191–200.[↩]

- Brown KH, Perez F, Peerson J, et al. Effect of dietary fiber (soy polysaccharide) on the severity, duration, and nutritional outcome of acute, watery diarrhea in children. Pediatrics 1993;92:241-7.[↩]

- Burks AW, Vanderhoof JA, Mehra S, Ostrom KM, Baggs G. Randomized clinical trial of soy formula with and without added fiber in antibiotic-induced diarrhea. J Pediatr 2001;139:578–82.[↩]

- Isolauri E, Juntunen M, Wiren S, Vuorinen P, Koivula T. Intestinal permeability changes in acute gastroenteritis: effects of clinical factors and nutritional management. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 1989;8:466–73.[↩]

- Sandhu BK; European Society of Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition Working Group on Acute Diarrhoea. Rationale for early feeding in childhood gastroenteritis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2001;33(Suppl 2):S13–6.[↩]

- Rabbani GH, Teka T, Zaman B, Majid N, Khatun M, Fuchs GJ. Clinical studies in persistent diarrhea: dietary management with green banana or pectin in Bangladeshi children. Gastroenterology 2001;121:554–60.[↩]

- Baker SS, Davis AM. Hypocaloric oral therapy during an episode of diarrhea and vomiting can lead to severe malnutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 1998;27:1–5.[↩]

- Checkley W, Gilman RH, Black R, et al. Effects of nutritional status on diarrhea in Peruvian children. J Pediatr 2002;140:210–8.[↩]

- Hambidge K. Zinc and diarrhea. Acta Pediatr Suppl 1992;381:82–6.[↩]

- Castillo-Duran C, Vial P, Uauy R. Trace mineral balance during acute diarrhea in infants. J Pediatr 1988;113:452–7.[↩]

- Sachdev HP, Mittal NK, Mittal SK, Yadav H. A controlled trial on utility of oral zinc supplementation in acute dehydrating diarrhea in infants. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 1988;7:877–81.[↩][↩]

- Roy SK, Behrens RH, Haider R, et al. Impact of zinc supplementation on intestinal permeability in Bangladeshi children with acute diarrhoea and persistent diarrhoea syndrome. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 1992;15:289–96.[↩]

- Sazawal S, Black RE, Bhan MK, Bhandari N, Sinha A, Jalla S. Zinc supplementation in young children with acute diarrhea in India. N Engl J Med 1995;333:839–44.[↩]

- Bhandari N, Bahl R, Taneja S, et al. Substantial reduction in severe diarrheal morbidity by daily zinc supplementation in young north Indian children. Pediatrics 2002;109:e86.[↩]

- Strand TA, Chandyo RK, Bahl R, et al. Effectiveness and efficacy of zinc for the treatment of acute diarrhea in young children. Pediatrics 2002;109:898–903.[↩]

- Penny ME, Peerson JM, Marin RM, et al. Randomized, community-based trial of the effect of zinc supplementation, with and without other micronutrients, on the duration of persistent childhood diarrhea in Lima, Peru. J Pediatr 1999;135(2 Pt 1):208–17.[↩]

- Bahl R, Bhandari N, Saksena M, et al. Efficacy of zinc-fortified oral rehydration solution in 6- to 35-month-old children with acute diarrhea. J Pediatr 2002;141:677–82.[↩]

- Sack DA, Islam S, Brown KH, et al. Oral therapy in children with cholera: a comparison of sucrose and glucose electrolyte solutions. J Pediatr 1980;96:20–5.[↩]

- Gremse DA. Effectiveness of nasogastric rehydration in hospitalized children with acute diarrhea. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 1995; 21:145–8.[↩]