Osteopetrosis

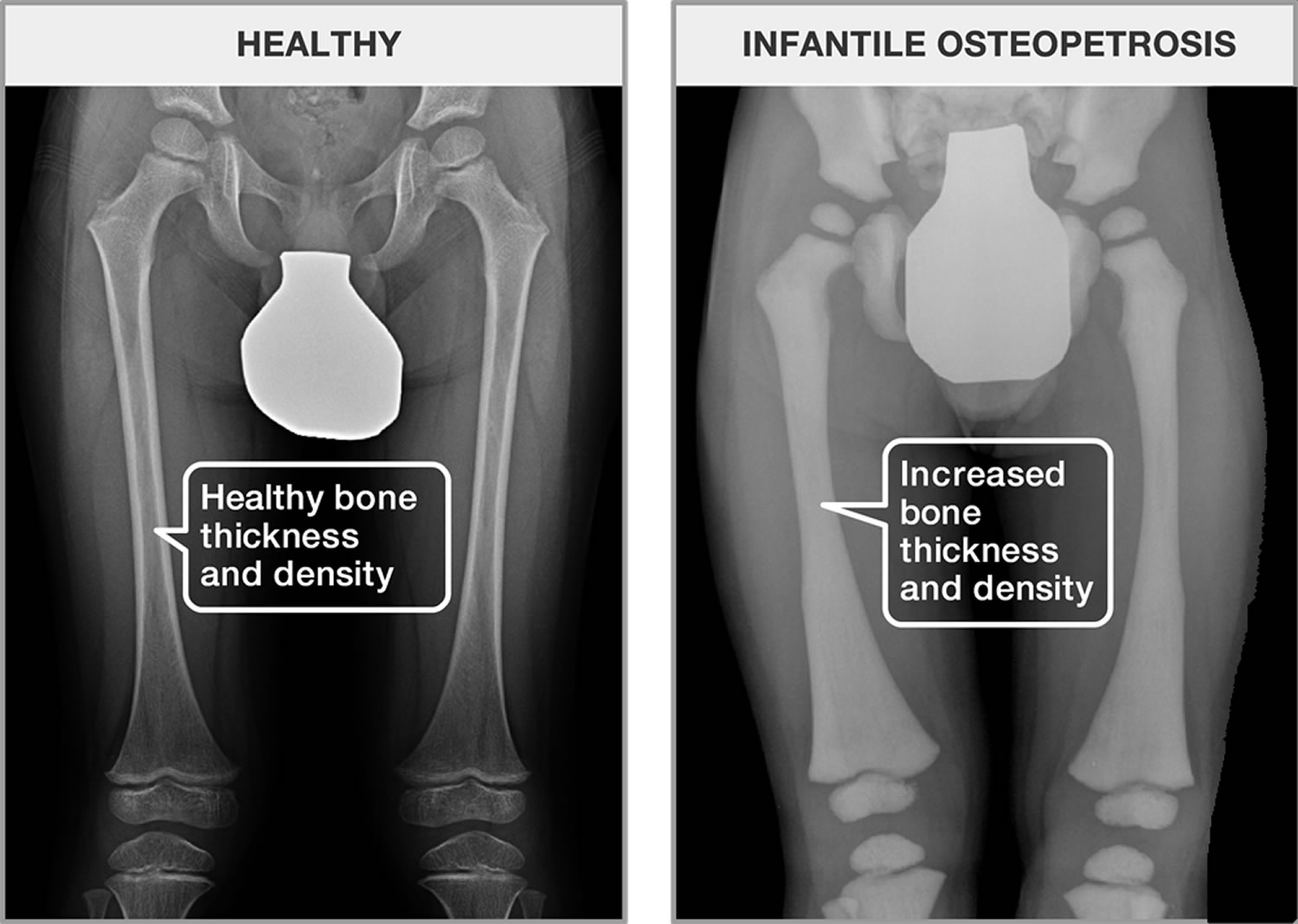

Osteopetrosis also called “marble bone disease”, refers to a group of rare, inherited skeletal disorders characterized by increased bone density, abnormal bone growth and abnormally brittle bones with fractures 1. This is the reason why osteopetrosis is often referred to as “marble bone disease”. In normal bone, the bone is continually being formed and broken down. This is done to repair damage and keep bone healthy. Keeping healthy bone requires a balance between cells that build bone (osteoblasts) and cells with break down bone (osteoclasts). The main problem in osteopetrosis is that osteoclasts don’t work well, whether because they lack ability to break down bone or because they aren’t present. Osteopetrosis symptoms and severity can vary greatly, ranging from neonatal onset with life-threatening complications such as bone marrow failure to the incidental finding of osteopetrosis on X-ray. Depending on severity and age of onset, features may include fractures, short stature, compressive neuropathies (pressure on the nerves), hypocalcemia with attendant tetanic seizures, and life-threatening pancytopenia. In rare cases, there may be neurological impairment or involvement of other body systems. Osteopetrosis may be caused by mutations in at least 10 genes. Researchers have described several major types of osteopetrosis, which are usually distinguished by their pattern of inheritance: autosomal dominant, autosomal recessive, or X-linked recessive with the most severe forms being autosomal recessive. The different types of osteopetrosis can also be distinguished by the severity of their signs and symptoms.

Autosomal dominant osteopetrosis, which is also called Albers-Schönberg disease, is typically the mildest type of the disorder. Some affected individuals have no symptoms. In these people, the unusually dense bones may be discovered by accident when an x-ray is done for another reason. In affected individuals who develop signs and symptoms, the major features of the condition include multiple bone fractures, abnormal side-to-side curvature of the spine (scoliosis) or other spinal abnormalities, arthritis in the hips, and a bone infection called osteomyelitis. These problems usually become apparent in late childhood or adolescence.

Autosomal recessive osteopetrosis is a more severe form of the disorder that becomes apparent in early infancy. Affected individuals have a high risk of bone fracture resulting from seemingly minor bumps and falls. Their abnormally dense skull bones pinch nerves in the head and face (cranial nerves), often resulting in vision loss, hearing loss, and paralysis of facial muscles. Dense bones can also impair the function of bone marrow, preventing it from producing new blood cells and immune system cells. As a result, people with severe osteopetrosis are at risk of abnormal bleeding, a shortage of red blood cells (anemia), and recurrent infections. In the most severe cases, these bone marrow abnormalities can be life-threatening in infancy or early childhood.

Other features of autosomal recessive osteopetrosis can include slow growth and short stature, dental abnormalities, and an enlarged liver and spleen (hepatosplenomegaly). Depending on the genetic changes involved, people with severe osteopetrosis can also have brain abnormalities, intellectual disability, or recurrent seizures (epilepsy).

A few individuals have been diagnosed with intermediate autosomal osteopetrosis, a form of the disorder that can have either an autosomal dominant or an autosomal recessive pattern of inheritance. The signs and symptoms of this condition become noticeable in childhood and include an increased risk of bone fracture and anemia. People with this form of the disorder typically do not have life-threatening bone marrow abnormalities. However, some affected individuals have had abnormal calcium deposits (calcifications) in the brain, intellectual disability, and a form of kidney disease called renal tubular acidosis.

Rarely, osteopetrosis can have an X-linked pattern of inheritance. In addition to abnormally dense bones, the X-linked form of the disorder is characterized by abnormal swelling caused by a buildup of fluid (lymphedema) and a condition called anhydrotic ectodermal dysplasia that affects the skin, hair, teeth, and sweat glands. Affected individuals also have a malfunctioning immune system (immunodeficiency), which allows severe, recurrent infections to develop. Researchers often refer to this condition as OL-EDA-ID, an acronym derived from each of the major features of the disorder.

Autosomal dominant osteopetrosis is the most common form of the disorder, affecting about 1 in 20,000 people 2. Autosomal recessive osteopetrosis is rarer, occurring in an estimated 1 in 250,000 people 2. Approximately eight to 40 children are born in the United States each year with the malignant infantile type of osteopetrosis. In the general population, one in every 250,000 individuals is born with this form of osteopetrosis. Higher rates have been found in specific regions of Costa Rica, the Middle East, Sweden and Russia. Males and females are affected in equal numbers.

The adult type of osteopetrosis affects about 1,250 individuals in the United States. The incidence is about one in every 20,000 individuals. Males and females are affected in equal numbers.

The X-linked form of osteopetrosis affects predominantly males due to the mode of inheritance of the mutation. Due to the rarity of cases, there are no population-wide studies.

Other forms of osteopetrosis are very rare. Only a few cases of intermediate autosomal osteopetrosis and OL-EDA-ID have been reported in the medical literature.

Osteopetrosis treatment depends on the specific symptoms and severity and may include vitamin D supplements, various medications, and/or surgery. Corticosteroids, such as prednisone, decrease the formation of new bone cells and may increase the rate of removal of old bone cells, strengthening bones. Corticosteroids may also help relieve bone pain and improve muscle strength. Bone marrow transplantation seems to have cured some infants with early-onset disease. However, the long-term prognosis after transplantation is unknown.

Adult osteopetrosis requires no treatment by itself, but complications may require intervention 3.

Fractures, anemia, bleeding, and infection require treatment.

If nerves going through the skull are compressed, surgery may be required to take pressure off the nerves. Surgery may also be needed to relieve increased pressure in the skull. Orthodontic treatment may be needed to correct distorted teeth. Plastic surgery may be done to correct severe deformities of the face and jaw.

Osteopetrosis causes

Mutations in at least nine genes cause the various types of osteopetrosis. Mutations in the CLCN7 gene are responsible for about 75 percent of cases of autosomal dominant osteopetrosis, 10 to 15 percent of cases of autosomal recessive osteopetrosis, and all known cases of intermediate autosomal osteopetrosis. TCIRG1 gene mutations cause about 50 percent of cases of autosomal recessive osteopetrosis. Mutations in other genes are less common causes of autosomal dominant and autosomal recessive forms of the disorder. The X-linked type of osteopetrosis, OL-EDA-ID, results from mutations in the IKBKG gene. In about 30 percent of all cases of osteopetrosis, the cause of the condition is unknown.

The genes associated with osteopetrosis are involved in the formation, development, and function of specialized cells called osteoclasts. These cells break down bone tissue during bone remodeling, a normal process in which old bone is removed and new bone is created to replace it. Bones are constantly being remodeled, and the process is carefully controlled to ensure that bones stay strong and healthy.

Mutations in any of the genes associated with osteopetrosis lead to abnormal or missing osteoclasts. Without functional osteoclasts, old bone is not broken down as new bone is formed. As a result, bones throughout the skeleton become unusually dense. The bones are also structurally abnormal, making them prone to fracture. These problems with bone remodeling underlie all of the major features of osteopetrosis.

Osteopetrosis inheritance pattern

Osteopetrosis can have several different patterns of inheritance. Most commonly, the disorder has an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern, which means one copy of an altered gene in each cell is sufficient to cause the disorder. Most people with autosomal dominant osteopetrosis inherit the condition from an affected parent.

Osteopetrosis can also be inherited in an autosomal recessive pattern, which means both copies of a gene in each cell have mutations. The parents of an individual with an autosomal recessive condition each carry one copy of the mutated gene, but they typically do not show signs and symptoms of the condition.

OL-EDA-ID is inherited in an X-linked recessive pattern. The IKBKG gene is located on the X chromosome, which is one of the two sex chromosomes. In males (who have only one X chromosome), one altered copy of the gene in each cell is sufficient to cause the condition. Males have a single X chromosome that is inherited from their mother and if a male inherits an X chromosome that contains an abnormal gene, he will develop osteopetrosis. In females (who have two X chromosomes), a mutation would have to occur in both copies of the gene to cause the disorder. Because it is unlikely that females will have two altered copies of this gene, males are affected by X-linked recessive disorders much more frequently than females. A characteristic of X-linked inheritance is that fathers cannot pass X-linked traits to their sons. Female carriers of an X-linked recessive disorder have a 25% chance with each pregnancy to have a carrier daughter like themselves, a 25% chance to have a non-carrier daughter, a 25% chance to have a son affected with the disease and a 25% chance to have an unaffected son.

Osteopetrosis intermediate type can be inherited as an autosomal recessive or autosomal dominant genetic trait.

People with specific questions about genetic risks or genetic testing for themselves or family members should speak with a genetics professional.

Resources for locating a genetics professional in your community are available online:

- The National Society of Genetic Counselors (https://www.findageneticcounselor.com/) offers a searchable directory of genetic counselors in the United States and Canada. You can search by location, name, area of practice/specialization, and/or ZIP Code.

- The American Board of Genetic Counseling (https://abgc.learningbuilder.com/Search/Public/MemberRole/Verification) provides a searchable directory of certified genetic counselors worldwide. You can search by practice area, name, organization, or location.

- The Canadian Association of Genetic Counselors (https://www.cagc-accg.ca/index.php?page=225) has a searchable directory of genetic counselors in Canada. You can search by name, distance from an address, province, or services.

- The American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (https://www.acmg.net/ACMG/Directories/ACMG/Directories.aspx) has a searchable database of medical genetics clinic services in the United States.

Osteopetrosis symptoms

Although osteopetroses comprise a range of different disorders, many of the same symptoms develop in most of them. Osteopetrosis is characterized by overly dense bones throughout the body. Bones thicken and break easily. Blood cells production may be impaired because there is less bone marrow, leading to anemia, infection, or bleeding.

An overgrowth of bone in the skull can cause pressure in the skull to increase; compress cranial nerves, causing facial paralysis or blindness or deafness; and can distort the face and teeth. The bones in the fingers and feet, the long bones of the arms and legs, the spine, and the pelvis may also be affected. Affected individuals may experience frequent infections of teeth and the bone in the jaw.

Osteopetrosis Autosomal Recessive (Malignant Infantile Type)

The most severe type of osteopetrosis, malignant infantile type, is apparent from birth, and if left untreated, can lead to death in the first decade of life. Symptoms vary depending on the exact gene change (mutation). Affected individuals may have an abnormally large head (macrocephaly). They may also have hydrocephalus, characterized by inhibition of the normal flow of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) within and abnormal widening (dilatation) of the cerebral spaces of the brain (ventricles), causing accumulation of CSF in the skull and potentially increased pressure on brain tissue. Symptoms that affect the eyes may include wasting away (atrophy) of the retina, eyes that appear widely spaced (hypertelorism), eyes that protrude from their orbits (exophthalmos), cross-eyes (strabismus), involuntary rhythmic movements of the eyes (nystagmus), and blindness.

Other symptoms associated with malignant infantile type of osteopetrosis include hearing loss, abnormally small jaw (micrognathia), chronic inflammation of the mucous membranes in the nose (rhinitis), eating difficulties and/or growth retardation. Some affected individuals experience delays in acquiring skills that require the coordination of muscles and voluntary movements (delayed psychomotor development). Some affected individuals may experience delayed tooth development or severe dental caries. In addition, abnormal enlargement of the liver and spleen (hepatosplenomegaly); abnormal hardening of some bones (osteosclerosis); fractures, usually of the ribs and long bones; inflammation of the lumbar vertebrae (osteomyelitis); increased density of the cranial bones (cranial hyperostosis) leading to nerve compression; and/or increased pressure inside the skull may also occur. Patients can also present with seizures due to low levels of calcium in the blood. Symptoms of severe neurodegeneration can manifest in rare variants of malignant infantile osteopetrosis.

Some affected individuals with the malignant infantile type of osteopetrosis may also experience consequences of reduced bone marrow space: marked deficiency of all types of blood cells (pancytopenia), the formation and development of blood cells outside the bone marrow, as in the spleen and liver (extramedullary hematopoiesis), and the occurrence of myeloid tissue in extramedullary sites (myeloid metaplasia). This may lead to frequent infections such as pneumonia and urinary tract infections. Affected individuals may also experience low levels of iron in red blood cells (anemia), due to both reduced bone marrow space and increased destruction of red blood cells due to an enlarged spleen. Of note, hematological defects usually present before neurological ones.

Osteopetrosis Autosomal Dominant (Adult Type)

A milder form of osteopetrosis, the adult type, is usually diagnosed in late childhood or adulthood. There is predominance of bone symptoms, including osteosclerosis, fractures after minimal trauma (usually of the ribs and long bones), osteomyelitis (especially of the jaw) and cranial hyperostosis. In some cases, affected individuals may have pus-filled sacs in the tissue around the teeth (dental abscess). In many cases, individuals may exhibit no symptoms (asymptomatic).

Affected individuals may also experience rhinitis, hepatosplenomegaly, anemia and extramedullary hematopoiesis.

Osteopetrosis Intermediate

The intermediate type is usually found in children and can be inherited as a autosomal recessive or autosomal dominant trait. The severity of the disease is variable. Symptoms may include abnormal hardening of some bones; fractures; osteomyelitis especially of the mandible, knees that are abnormally close together and ankles that are abnormally wide apart (genu valgum) and cranial hyperostosis.

Symptoms of the intermediate type of osteopetrosis may also include gradual deterioration of the nerves of the eyes (optic atrophy), loss of vision, muscular weakness, and rhinitis. Some affected individuals may experience abnormal protrusion of the lower jaw (mandibular prognathism), dental anomalies, baby teeth that do not fall out (deciduous retention), tooth crown malformation, dental caries, and facial paralysis. Other symptoms include hepatosplenomegaly, anemia, decreased levels of circulating blood platelets (thrombocytopenia), pancytopenia, and extramedullary hematopoiesis.

Osteopetrosis X-linked Recessive

X-linked osteopetrosis is extremely rare but severe, with only a few cases reported worldwide. In addition to classical symptoms linked with osteopetrosis, it is associated with immunodeficiency, localized fluid retention and tissue swelling (lymphedema) as well as abnormalities of the hair, skin, nails and sweat glands (ectodermal dysplasia).

Osteopetrosis complications

One of the most difficult concepts for both patients and physicians who study osteopetrosis to understand is the tremendous variability in disease severity among people with the same mutations, even within the same family. For example, someone with severe disease can have a child who is a non-penetrant carrier (i.e. has the disease causing mutation, but doesn’t have the disease) or someone with very mild disease can have a child with severe disease. No one understands why there is such variability in disease severity, but it is something that has been observed by physicians who take care of families with this condition. Fractures are the most common complication of osteopetrosis. However, the number of fractures per patient is highly variable. Some people only have a few fractures and others can have over 100 fractures. Many fractures occur without significant trauma and sometimes they don’t heal (nonunion). Additionally, if the fracture requires surgery the bone is often difficult to operate on because it is both very hard and brittle.

Osteonecrosis (death of bone tissue) generally presents as a non-healing piece of bone, most typically in the jaw or upper mouth. Osteonecrosis occurs in 11-16% of adult patients. The dead bone frequently becomes infected and can be very difficult to treat. Osteonecrosis often looks like a non-healing sore in the mouth with exposed bone. Sometimes it can occur after a dental extraction.

Visual loss (blindness and other less severe visual problems) is more common with severe recessive forms of osteopetrosis. Visual loss can occur when the optic nerve grows, but the hole in the skull (called a foramen) doesn’t get bigger and traps the nerve, choking it off. Rates of blindness vary from study to study with a range of 5-19%. Blindness can be prevented by following a patient carefully and promptly referring the child to a neurosurgeon, who can operate to relieve this problem, if necessary.

Bone marrow failure generally only occurs in the most severely affected patients, such as in infantile recessive osteopetrosis. In these patients bone replaces bone marrow (blood cells are made in bone marrow) and can cause them to become anemic. In contrast, this complication only occurs in <3% of dominant osteopetrosis patients.

Osteopetrosis diagnosis

The diagnosis of osteopetrosis starts with clinical suspicion of the condition. This can be problematic, as many clinicians are unfamiliar with osteopetrosis and how it is diagnosed. A diagnosis of osteopetrosis is based on a thorough clinical evaluation, detailed patient history, and a variety of specialized tests such as x-ray imaging and measurement of bone mass density (BMD) which is increased. Skeletal X-ray findings are very specific and are considered sufficient to make a diagnosis. Biochemical findings like increased concentration of creatinine kinase BB isoenzyme and tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) can also help making the diagnosis.

Clinical Testing and Work-Up

Genetic testing can pinpoint the mutation in over 90% of cases: this can identify forms of osteopetrosis with unique clinical associations or complications and direct the management plan. A bone biopsy is sometimes performed to confirm the diagnosis, but not routinely done as it is an invasive procedure with non-negligible risks.

Once the diagnosis is made, the following blood tests should be done: serum calcium, parathyroid hormone, phosphorus, creatinine, 25-hydroxyvitamin D, complete blood count with differential, creatine kinase isoenzymes (specifically the BB isozyme of creatine kinase), and lactate dehydrogenase. These measurements will determine the need for supplementation and for referral to specialists. Baseline magnetic resonance imaging of the brain should be arranged to evaluate cranial nerve involvement, hydrocephalus and vascular abnormalities. Affected individuals should be evaluated regularly by an ophthalmologist for optic nerve involvement, and benefit from a multidisciplinary approach including endocrinology, ophthalmology, genetics, and dentistry, with input from orthopedics, otorhinolaryngology, neurology, neurosurgery, nephrology, infectious disease and hematology specialists as needed.

Prenatal diagnosis is theoretically possible in families in whom the genetic mutation has been identified.

Osteopetrosis treatment

At present, the only established cure for autosomal recessive malignant infantile osteopetrosis is hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) for specific cases. This allows the restoration of bone resorption by donor-derived osteoclasts. Genetic studies are important to determine whether bone marrow transplant is appropriate, as certain specific mutations will not benefit from the transplant (those in the RANKL gene); moreover, some patients (all those with mutations in the OSTM1 gene and some of those with two mutations in the CLCN7 gene) develop progressive neurodegeneration, which is not cured by hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. In mild forms of osteopetrosis it is important to weight the risks and benefits as they may not warrant the dangerous risks associated with hematopoietic stem cell transplantation like rejection, severe infections and very high levels of calcium in the blood leading to a significant mortality rate in the first year. For patients in whom hematopoietic stem cell transplantation has been deemed not appropriate, corticosteroids may be considered, but there is not enough evidence to support their routine use.

Gamma-1b (Actimmune) was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to delay disease progression in individuals with severe malignant infantile osteopetrosis. Actimmune is manufactured by Horizon Pharma. Inc.

Good nutrition is very important for patients with osteopetrosis, including the use of calcium and vitamin D supplements if there are low levels of calcium in the blood. Other treatments are symptomatic and supportive. Genetic counseling is recommended for families in which this disorder occurs.

Osteopetrosis prognosis

Early-onset osteopetrosis that is not treated with bone marrow transplantation usually causes death during infancy or early childhood. Death usually results from anemia, infection, or bleeding. Late-onset osteopetrosis is often very mild.