Patella dislocation

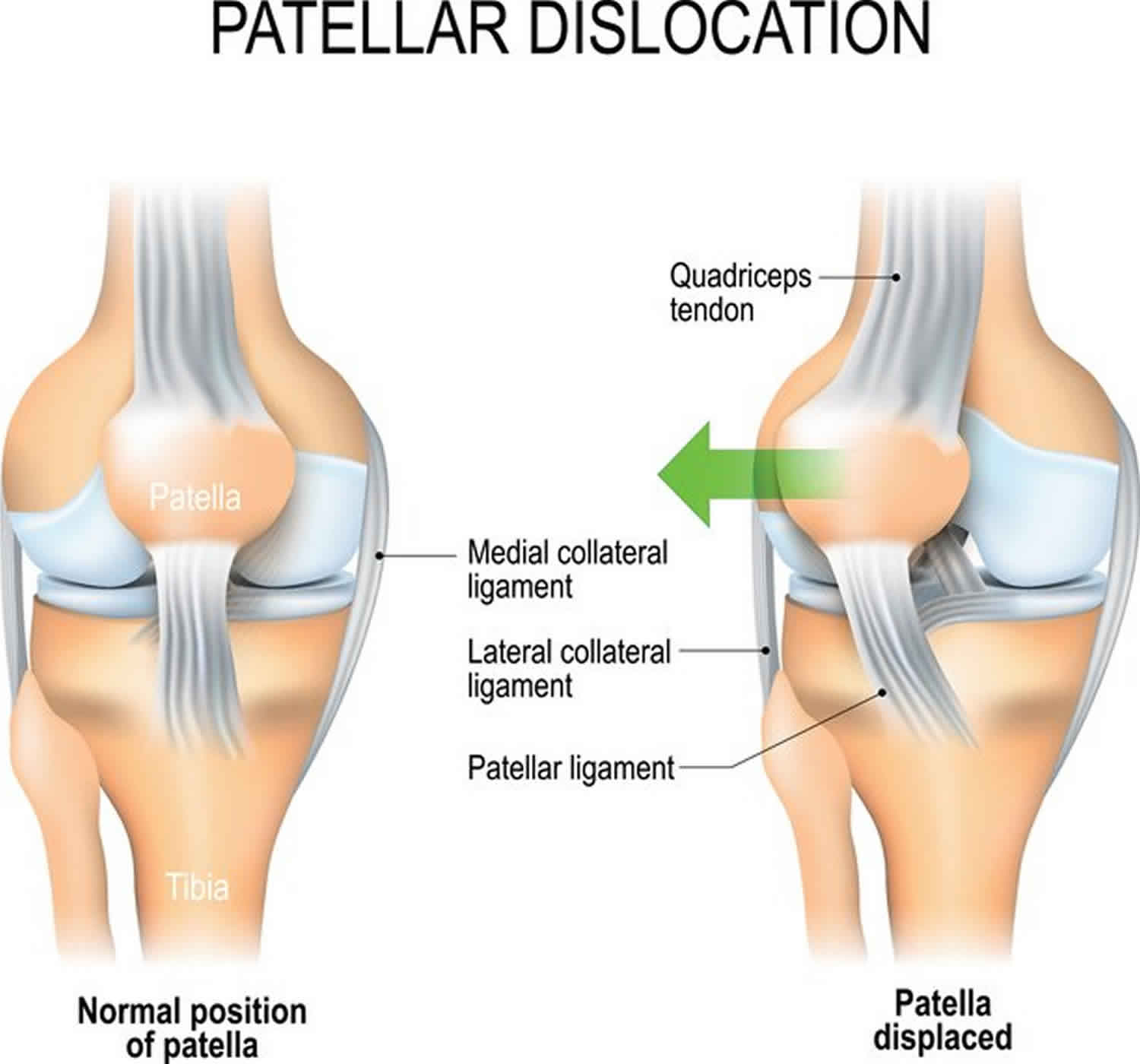

Patella dislocation also called kneecap dislocation, occurs when the triangle-shaped bone covering the knee (patella) moves or slides out of place. Patella dislocation usually occurs as a result of sudden direction changes while running and the knee is under stress or it may occur as a direct result of injury. Patella dislocation often occurs toward the outside of the leg. Patients typically present with obvious deformity and an inability to extend the knee. When the patella slips out of place — whether a partial or complete dislocation — it typically causes pain and loss of function. Even if the patella slips back into place by itself, it will still require treatment to relieve painful symptoms. Be sure to see your doctor for a full examination to identify any damage to the knee joint and surrounding soft tissues.

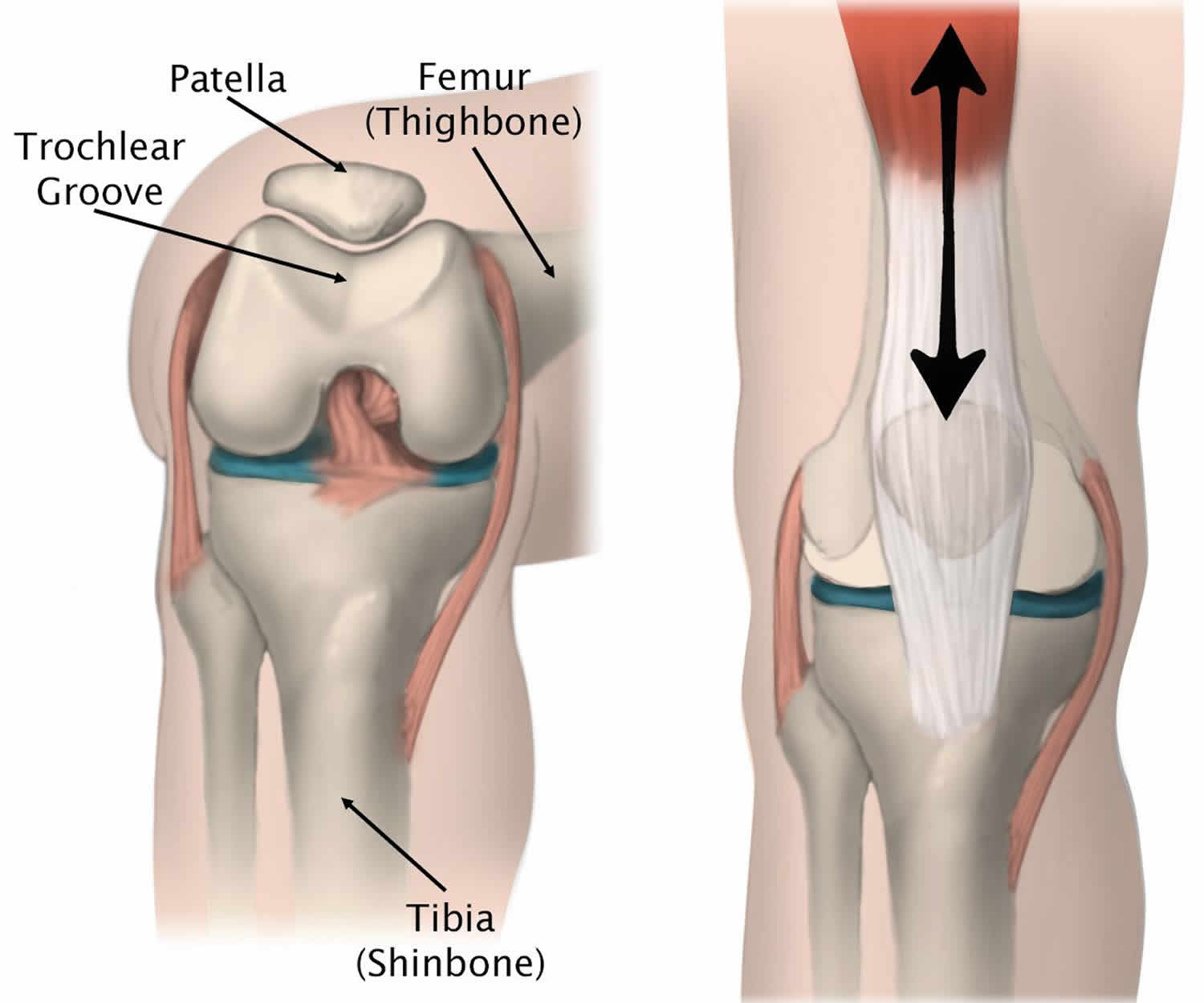

Your kneecap (patella) sits over the front of your knee joint. As you bend or straighten your knee, the underside of your kneecap glides over a groove in the bones that make up your knee joint.

- A kneecap that slides out of the groove partway is called a subluxation.

- A kneecap that moves fully outside the groove is called a dislocation.

Patellar instability is a spectrum of conditions ranging from intermittent subluxation to dislocation 1. Generalized patellar instability is thought to represent up to 3% of clinical presentations involving the knee.

There are several varieties of patellar dislocation, as follows:

- Lateral – The most common type of patellar dislocation

- Horizontal – A rare occurrence, in which the patella has rotated on its horizontal axis with the articular surfaces facing either proximally or distally

- Vertical – Also a very uncommon event, in which the patella rotates around its vertical axis with impaction of one of the lateral surfaces in the intercondylar notch of the femur

- Intercondylar – Any type of dislocation in which the patella remains in its anatomic position and may be rotated around its vertical or horizontal axis

Several anatomic factors, including a lateralized tibial tubercle 2, the tibial tuberosity–trochlear groove distance 3, the tibial tuberosity–posterior cruciate ligament distance 4, the shape and dimensions of the patella 5 and the width of the patellar tendon 6, may increase the likelihood of lateral patellar dislocation.

A kneecap can be knocked out of the groove when the knee is hit from the side.

A kneecap can also slide out of the groove during normal movement or when there is twisting motion or a sudden turn.

Patellar subluxation or dislocation may occur more than once. The first few times it happens will be painful, and you will be unable to walk.

If subluxations continue to occur and are not treated, you may feel less pain when they happen. However, there may be more damage to your knee joint each time it happens.

Patella dislocations account for approximately 2 to 3% of knee injuries. The reported incidence of patellar dislocation is 5.8 per 100,000, but it may be as high as 29 per 100,000 in the adolescent population 7. Patella dislocation tends to affect young, active individuals with adolescent females and athletes at higher risk. Incidence is reported as 5.8 per 100,000 but could be as high as 29 per 100,000 in the adolescent population 8. Acute dislocations tend to occur relatively equally in males and females. Patella dislocations are most common in the second and third decades of life. The recurrence rate following a first-time patellar dislocation can be 15 to 60% 9.

In most cases, patellar dislocation can be managed conservatively with physiotherapy and bracing except in the presence of a fracture or recurrent episodes.

First Aid

If you can, straighten out your knee. If it is stuck and painful to move, stabilize (splint) the knee and get medical attention.

Your health care provider will examine your knee. This may confirm that the kneecap is dislocated.

Your provider may order a knee x-ray or an MRI. These tests can show if the dislocation caused a broken bone or cartilage damage. If tests show that you have no damage, your knee will be placed into an immobilizer or cast to prevent you from moving it. You will need to wear this for about 3 weeks.

Once you are no longer in a cast, physical therapy can help build back your muscle strength and improve the knee’s range of motion.

If there is damage to the bone and cartilage, or if the kneecap continues to be unstable, you may need surgery to stabilize the kneecap. This may be done using arthroscopic or open surgery.

Figure 1. Normal patella location

Footnote: (Left) The patella normally rests in a small groove at the end of the femur called the trochlear groove. (Right) As you bend and straighten your knee, the patella slides up and down within the groove.

Figure 2. Patellar dislocation

See your doctor if you injure your knee and have symptoms of patellar dislocation.

See your doctor if:

- Your knee feels unstable.

- Pain or swelling returns after having gone away.

- Your injury does not seem to be getting better with time.

- You have pain when your knee catches and locks.

See your doctor if you are being treated for a dislocated knee and you notice:

- Increased instability in your knee

- Pain or swelling return after they went away

- Your injury does not appear to be getting better with time

Also see your doctor if you re-injure your knee.

Patellar dislocation causes

Kneecap (patella) often occurs after a sudden change in direction when your leg is planted. A common mechanism is external tibial rotation with the foot fixed on the ground. This puts your kneecap under stress. This can occur when playing certain sports, such as basketball.

Acute patellar dislocation may also occur as result of direct trauma, usually a direct blow, often to the medial aspect of the knee.

When the kneecap is dislocated, it can slip sideways to the outside of the knee.

There is also a group of patients that suffer from chronic laxity and recurrent subluxation of their patella.

- A shallow or uneven groove in the femur can make dislocation more likely.

- Some people’s ligaments are looser, making their joints extremely flexible and more prone to patellar dislocation. This occurs more often in girls, and the problem may affect both knees.

- People with cerebral palsy and Down syndrome may have kneecaps that dislocate frequently due to imbalance and muscle weakness.

- Rarely, children are born with unstable kneecaps causing dislocations at a very early age, often without pain.

Anatomic variation including patella alta and patellar dysplasia and trochlear dysplasia can also predispose individuals to dislocation. Ligamentous laxity as a result of female gender or secondary to connective tissue disorders such as Marfan Syndrome or Ehlers-Danlos increases the risk of dislocation. Muscular imbalance, particularly weakness of the vastus medialis oblique also contributes.

Habitual dislocations are characterized by painless dislocation every time the knee flexes, which is usually as a result of abnormal tightness of vastus lateralis and the iliotibial band.

Congenital dislocations can occur, the most common association being Down syndrome; this is as a result of a small patella in combination with a hypoplastic condyle and typically requires surgical intervention to reduce it.

Patellar dislocation pathophysiology

Patellar dislocations tend to occur in a lateral direction which is partly because the direction of pull of quadriceps muscle is slightly lateral to the mechanical axis of the limb 1. Medial instability is rare and more likely to result from congenital conditions, quadriceps atrophy, or iatrogenically. Intra-articular dislocation is also uncommon but can occur following trauma where the patella is avulsed from the quadriceps tendon and then rotated. Superior dislocations can occur in elderly patients where forced hyperextension causes the patella to lock on an anterior femoral osteophyte.

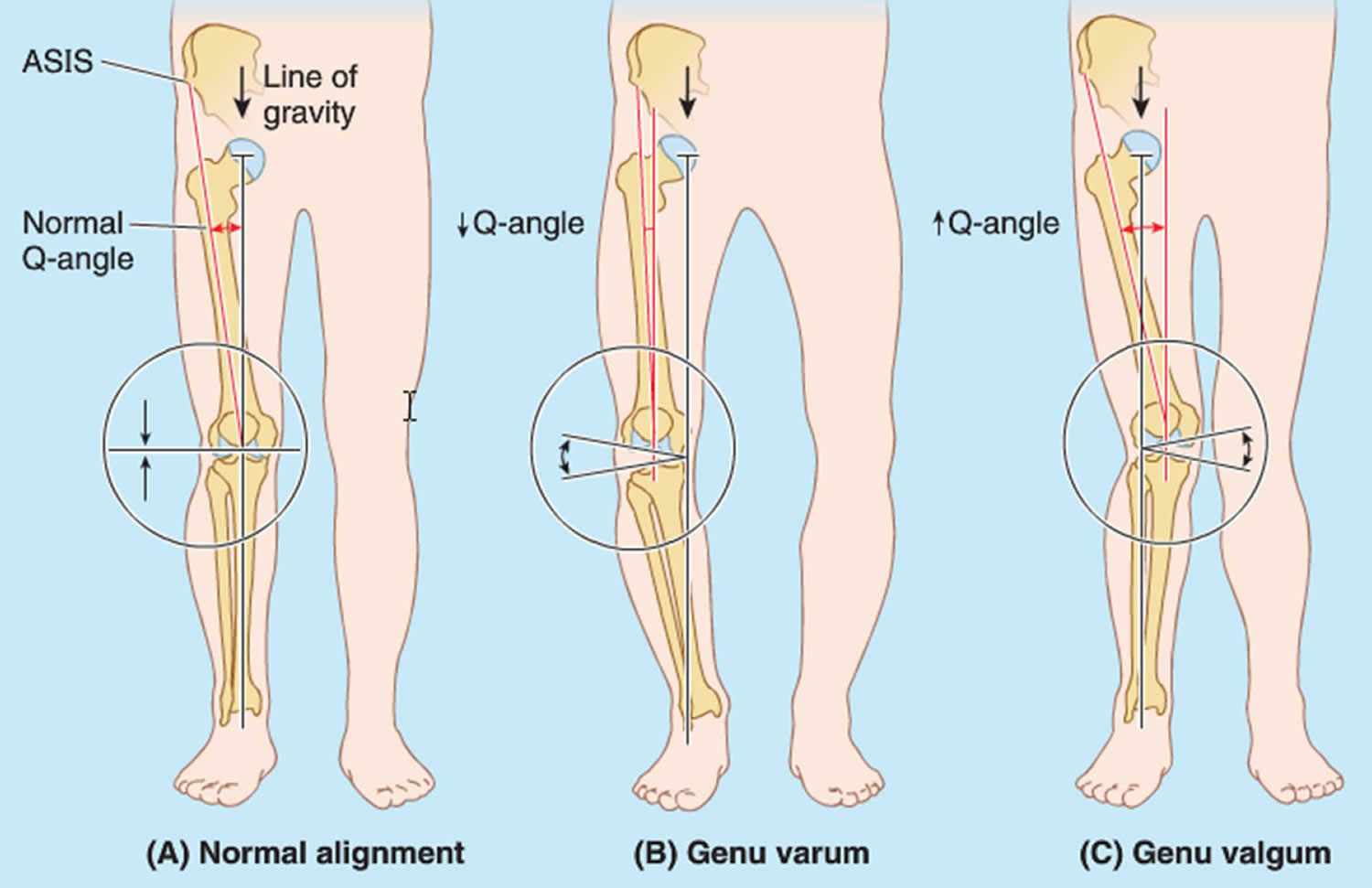

Individuals with an increased Q-angle are predisposed to dislocation (Figure 3). The Q angle forms from a line drawn from the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) through the center of the patella, then a second line drawn from the center of the patella to the tibial tubercle. In females, this measurement is typically higher than males, 18 degrees compared to 14 degrees. A high Q angle measures as 15 degrees in males and 20 degrees in females.

There are static and dynamic stabilizers of the patella. The dynamic stabilizers are the soft tissues. The vastus medialis obliquus muscle is the most distal portion of the quadriceps muscle and exerts a medially directed pull which helps to maintain patella position. Weakness or dysplasia of this muscle makes dislocation more likely. The medial retinaculum of the knee joint capsule is reinforced by the medial patellofemoral ligament which prevents excessive lateral movement of the patella and usually suffers damage in acute dislocations.

The static stabilizers relate to the bone. Anatomical factors that predispose to dislocation include patella alta or high riding patella (as it does not articulate with the sulcus, the constraint is lost), trochlear dysplasia, excessive lateral patella tile, lateral femoral condyle hypoplasia — distortion of the normal anatomy results in loss of stability. “Miserable malalignment syndrome” also correlates; this includes femoral anteversion, genu valgum, external tibial torsion/pronated feet.

Figure 3. Q-angle

Patellar dislocation prevention

Use proper techniques when exercising or playing sports. Keep your knees strong and flexible.

Some cases of knee dislocation may not be preventable, especially if physical factors make you more likely to dislocate your knee.

Patellar dislocation symptoms

Patients typically describe pain and deformity of the knee following a direct blow or sudden change in direction in which the knee gives way. Patients may report feeling a ‘pop.’ For those with long-standing instability, pain is classically located in front and toward the middle (anteromedially). Patients may report giving way, clicking and catching. Symptoms are usually worse on flexion and kneeling.

Symptoms of patellar dislocation include:

- Knee appears to be deformed

- Knee is bent and cannot be straightened out

- Kneecap (patella) dislocates to the outside of the knee

- Knee pain and tenderness

- Knee swelling

- “Sloppy” kneecap — you can move the kneecap too much from right to left (hypermobile patella)

The first few times this occurs, you will feel pain and be unable to walk. If you continue to have patellar dislocations, your knee may not hurt as much and you may not be as disabled. This is not a reason to avoid treatment. Kneecap dislocation damages your knee joint. It can lead to cartilage injuries and increase the risk of developing osteoarthritis at a younger age.

On examination of an acute dislocation, a joint effusion or bleeding into a joint cavity (hemarthrosis) is a typical finding but is less likely in the case of chronic patellar dislocation. It is a frequent cause of hemarthrosis. On general inspection with the patient standing there may be signs of femoral anteversion, patella alta, tibial torsion, genu recurvatum, genu valgum or varum, pes planus and general ligamentous laxity. Next, the knee and surrounding structures should be palpated, covering the superior, inferior, medial and lateral poles of the patella. If pain permits, flexion, and extension should be checked, feeling for any crepitus or restriction of movement. Assessment of the collateral and cruciate ligaments in also necessary.

The J sign may be present; the patella tends to deviate laterally during knee extension. In a normal knee, the patella can be moved medially and laterally between twenty-five and fifty percent the width of the patella. In recurrent dislocators, it may move further (patellar glide). They may have a positive apprehension test whereby the knee is held relaxed in 20 to 30 degrees fo flexion and attempted lateral subluxation. They will be tender over the medial patellar retinaculum and will have a positive patellar apprehension test.

Patellar dislocation diagnosis

You may have had a knee x-ray or an MRI to make sure your kneecap bone did not break and there was no damage to the cartilage or tendons (other tissues in your knee joint).

Plain x-ray

It is necessary to get anteroposterior (AP) and lateral radiographs of the affected knee, as well as axial (sunrise) views 10. These will help identify fracture, the presence of loose bodies, malalignment or arthritic changes. There can be associated avulsion fracture of the medial patellofemoral ligament (middle third of patella). It will also be possible to identify any potential risk factors for dislocation such as patella alta; there may be disruption of the Blumensaat line whereby the lower pole of the patella should lie on a line drawn anteriorly from the intercondylar notch with the knee flexed to 30 degrees. The Insall-Salvati ratio is the ratio measuring the length of the patella ligament (LL; from the inferior patellar pole to the tibial tubercle) and the patellar length (LP; the longest diagonal length of the patella). A normal ratio is 1.0; a ratio of 1.2 suggests patella alta and 0.8 patella baja. If there is acute patellar dislocation, then this may be evident on the lateral view.

The lateral view can also allow assessment of trochlear dysplasia. The ‘crossing sign’ is present when the trochlear groove is in the same plane as the anterior border of the lateral condyle, suggestive of flattening. The ‘double contour sign’ is present if the patient has a convex trochlear groove or underdeveloped medial condyle. It occurs when the anterior border of the lateral condyle is in front of the anterior border of the medial condyle. The Merchant view is for assessment of patellar tilt and is an axial view at 45 degrees of flexion; the sulcus and congruence angles can be examined. Weight-bearing views can be helpful to assess deformity and radiographs of the contralateral knee.

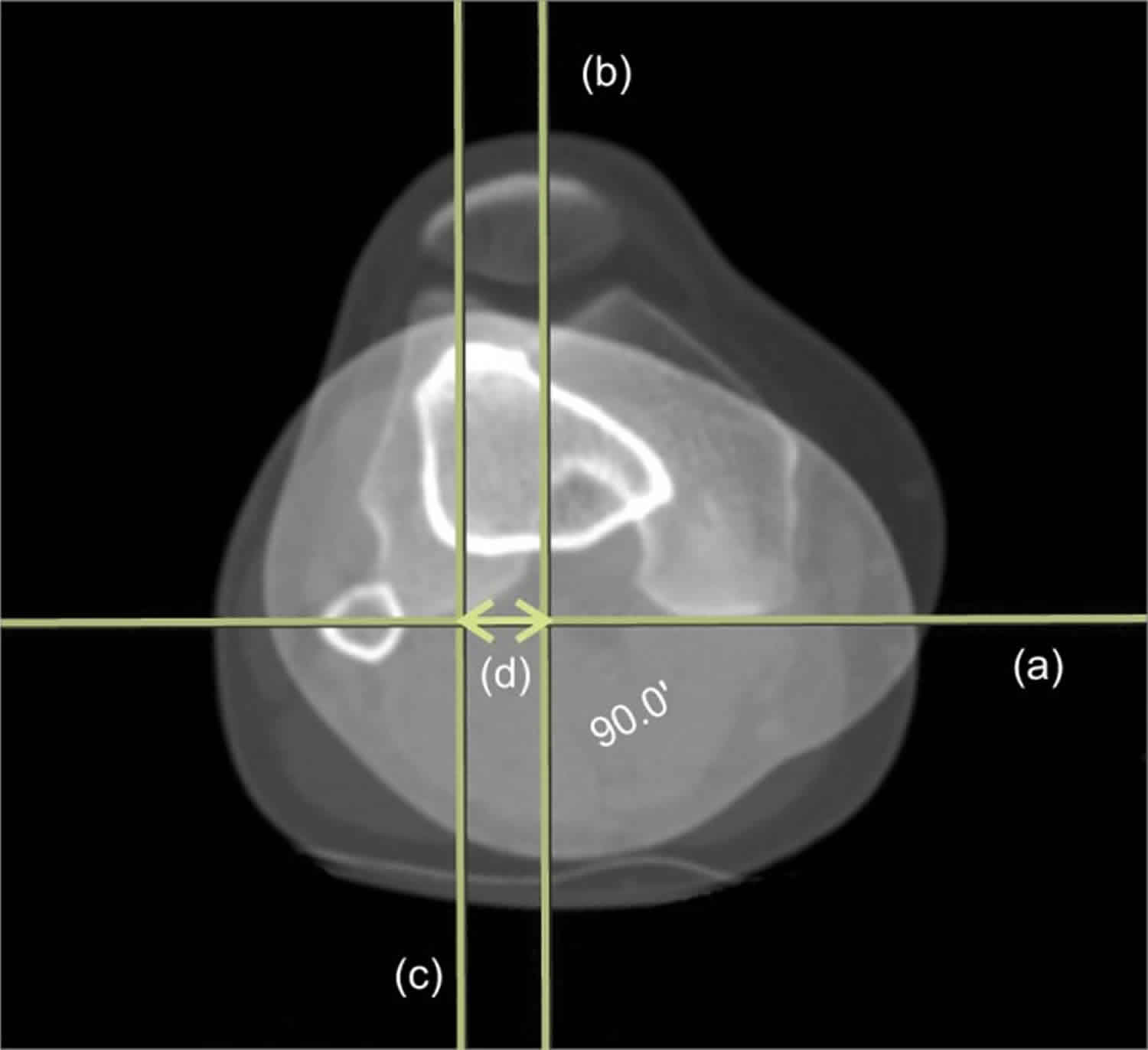

Computer Tomography Scans (CT)

CT scan allows measurement of the tibial tuberosity-trochlear groove (TT-TG) distance; this is the distance between two perpendicular lines; one from the posterior cortex to the tibial tubercle and one from the posterior cortex to the trochlear groove and is normally less than 20mm. A measurement of 21-40mm is borderline and over 40mm abnormal. They can also show osteochondral fractures.

Figure 4. Tibial tuberosity-trochlear groove distance

Footnote: A line tangent to the posterior epicondyle (a) and a perpendicular line through the deepest point of trochlea (b) are drawn. Another line parallel to the trochlea line through the most anterior portion of the tibial tuberosity (c) is drawn. Tibial tuberosity-trochlear groove distance (d) is measured between line (b) and (c).

[Source 11 ]Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

Magnetic resonance imaging is the diagnostic gold standard. If there has been a complete dislocation, there is typically a characteristic bruising pattern of the lateral femoral condyle and medial patella. There may be disruption of the medial patellofemoral ligament (usually at the patellar insertion) 12. It can be a helpful medium to diagnose articular cartilage damage on the medial patellar facet and is more sensitive in detecting osteochondral lesions. It can also aid the classification of trochlear dysplasia should it be present. This rating is done using Dejour’s classification and has four grades; type A is flatter than normal with a sulcus angle greater than 145 degrees, type B which is flat, type C which is convex, and type D which is convex with a supratrochlear spur.

Patellar dislocation treatment

If tests show that you do not have damage:

- Your knee may be placed in a brace, splint, or cast for several weeks.

- You may need to use crutches at first so that you do not put too much weight on your knee.

- You will need to follow up with your primary care provider or a bone doctor (orthopedist).

- You may need physical therapy to work on strengthening and conditioning.

- Most people recover fully within 6 to 8 weeks.

If your kneecap is damaged or unstable, you may need surgery to repair or stabilize it. Your health care provider will most often refer you to an orthopaedic surgeon.

Acute patellar dislocations

Acute management of an unreduced patella dislocation is to reduction. This procedure can be done in the emergency department with some sedation as needed. The reduction process involves flexing the hip, applying pressure in a medial direction to the patella while slowly extending the knee. It is also possible to perform with the patient sitting up with legs hanging off the side of the trolley.

The mainstay of treatment for first-time dislocators without evidence of loose bodies or intra-articular damage is analgesia, physiotherapy and activity modification. Bracing in a J brace or patellar stabilizing sleeve may be beneficial short term (3 to 4 weeks) to allow soft tissues to heal. Subsequent management is by physiotherapy input with an emphasis on quadriceps and vastus medialis oblique strengthening, which is often curative. The patient can be allowed to weight bear as tolerated.

There remains debate on the role of surgical management of acute dislocations. A recent Cochrane review revealed that, although there was some evidence in support of surgical management, the quality of the evidence was insufficient to support a change in current practice 13. Some surgeons advocate performing arthroscopy if there is high suspicion of osteochondral fracture, with open repair of the fragment if necessary 14.

Symptom relief

Sit with your knee raised at least 4 times a day. This will help reduce swelling.

Ice your knee. Make an ice pack by putting ice cubes in a plastic bag and wrapping a cloth around it.

- For the first day of injury, apply the ice pack every hour for 10 to 15 minutes.

- After the first day, ice the area every 3 to 4 hours for 2 or 3 days or until the pain goes away.

Pain medicines such as acetaminophen, ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin, and others), or naproxen (Aleve, Naprosyn, and others) may help ease pain and swelling.

- Be sure to take these only as directed. Carefully read the warnings on the label before you take them.

- Talk with your doctor before using these medicines if you have heart disease, high blood pressure, kidney disease, liver disease, or have had stomach ulcers or internal bleeding in the past.

Activity

You will need to change your activity while you are wearing a splint or brace. Your doctor will advise you about:

- How much weight you can place on your knee

- When you can remove the splint or brace

- Bicycling instead of running while you heal, especially if your usual activity is running

Many exercises can help stretch and strengthen the muscles around your knee, thigh, and hip. Your doctor may show these to you or may have you work with a physical therapist to learn them.

Before returning to sports or strenuous activity, your injured leg should be as strong as your uninjured leg. You should also be able to:

- Run and jump on your injured leg without pain

- Fully straighten and bend your injured knee without pain

- Jog and sprint straight ahead without limping or feeling pain

- Be able to do 45- and 90-degree cuts when running

Patella dislocation surgery

Surgical management can be a consideration in several situations 14:

- A first time patellar dislocation with osteochondral fracture/loose body

- MRI demonstrated substantial disruption of medial patellofemoral ligament

- Subluxed patella on Merchant radiograph view with a normal contralateral knee

- Failure to improve with conservative management with anatomical factors which predispose to dislocation

- Recurrent patellar dislocations

There is evidence which suggests that early stabilization procedures can reduce the rate of subsequent patellar dislocations but in the absence of clear subjective benefits at long term follow up 15.

Surgical management is usually via proximal and distal realignment. There are numerous surgical options available:

Arthroscopy +/- open debridement

Arthroscopic or open debridement with removal of any loose bodies may be necessary for displaced osteochondral fractures or loose bodies.

Medial patellofemoral ligament re-attachment or reconstruction (proximal realignment)

Proximal realignment constitutes reconstruction of the medial patellofemoral ligament. In brief, to repair the ligament, a longitudinal incision is made at the border of the vastus medialis oblique muscle, just anterior to the medial epicondyle. The ligament is usually re-attached to the femur using bone anchors. If the patient has had recurrent dislocations, then reconstruction may be necessary by harvesting gracilis or semitendinosus which are then attached to the patella and femur.

Isolated repair/reconstruction of the medial patellofemoral ligament is not a recommendation in those with bony abnormalities including tibial tuberosity-trochlear groove (TT-TG) distance greater than 20mm, convex trochlear dysplasia, severe patella alta, advanced cartilage degeneration or severe femoral anteversion 9.

Lateral release (distal realignment)

A lateral release cuts the retinaculum on the lateral aspect of the knee joint. The aim is to improve the alignment of the patella by reducing the lateral pull.

Osteotomy (distal realignment)

Where there is abnormal anatomy contributing to poor patella tracking and a high tibial tuberosity-trochlear groove (TT-TG) distance, the alignment correction can be through an osteotomy. The most common procedure of this type is known as the Fulkerson-type osteotomy and involves an osteotomy as well as removing the small portion of bone to which the tendon attaches and repositioning it in a more anteromedial position on the tibia.

If the patient has patella alta, osteotomy also allows the surgeon to effectively lower the patella, thereby reducing the distance between it and the trochlea groove, which is achievable by moving the tibial tubercle to a more distal position.

Where there is a rotational deformity, derotational osteotomies of the femur may be a therapeutic consideration. These procedures are not appropriate in patients with open growth plates

Trochleoplasty

Trochleoplasty is indicated in recurrent kneecap dislocators with a convex or flat trochlea. The trochlear groove is deepened to create a groove for the patella to glide through; this may take place alongside an medial patellofemoral ligament reconstruction. Studies suggest it is not advisable in those with open growth plates or severely degenerative joint. This procedure is uncommon except in refractory cases.

Patellar dislocation complications

Complications of the acute dislocation include associated osteochondral fracture, the risk of recurrence, and degenerative arthritis.

General surgical complications include infection, neurovascular injury, deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism.

Complications specific to medial patellofemoral ligament surgery include saphenous nerve neuritis and rupture.

Following osteotomy, patients often complain of pain over the screw site. There may be a loss of ability to kneel comfortably. There is also a risk of proximal tibial fracture.[11]

Even following surgery, there remains a risk of recurrent lateral patellar instability.

Patellar dislocation prognosis

Physiotherapy can be necessary for as long as two to three months following an initial dislocation. Physiotherapy is vital as if the medial retinaculum does not heal and the vastus medialis oblique muscle does not adequately rehabilitate, recurrent dislocation will ensue. Studies suggest there is a 20 to 40% risk of dislocating again, with even higher rates following a second dislocation 16.

It is common for patients to remain symptomatic after the first dislocation. Atkin et al. found that at 6 months, 58% of patients experience limitation in strenuous activities 17. Although the range of motion was regained, participation in sports was reduced in the first 6 months following injury; kneeling and squatting were particularly challenging. Failure to return to sport occurred in 55%. Maenpaa et al. 18 found that over 50 percent of patients have complications following a first-time dislocation; including redislocation and patellofemoral pain or subluxation.

Those patients with abnormal anatomy triggering dislocations may suffer dislocations on the contralateral side and require surgery there too. Stability, however, tends to increase with advancing age of the patient.

After a second dislocation, studies suggest the risk of dislocation goes up to just under fifty percent 9.

- Hayat Z, Case JL. Patella Dislocation. [Updated 2019 Jun 3]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2019 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538288[↩][↩]

- Balcarek P, Jung K, Frosch KH, Stürmer KM. Value of the tibial tuberosity-trochlear groove distance in patellar instability in the young athlete. Am J Sports Med. 2011 Aug. 39(8):1756-61.[↩]

- Mohammadinejad P, Shekarchi B. Value of CT scan-assessed tibial tuberosity-trochlear groove distance in identification of patellar instability. Radiol Med. 2016 Sep. 121 (9):729-34.[↩]

- Daynes J, Hinckel BB, Farr J. Tibial Tuberosity-Posterior Cruciate Ligament Distance. J Knee Surg. 2016 Aug. 29 (6):471-7.[↩]

- Panni AS, Cerciello S, Maffulli N, Di Cesare M, Servien E, Neyret P. Patellar shape can be a predisposing factor in patellar instability. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2011 Apr. 19(4):663-70.[↩]

- Yılmaz B, Çiçek ED, Şirin E, Özdemir G, Karakuş Ö, Muratlı HH. A magnetic resonance imaging study of abnormalities of the patella and patellar tendon that predispose children to acute patellofemoral dislocation. Clin Imaging. 2017 Mar – Apr. 42:83-87.[↩]

- Mehta VM, Inoue M, Nomura E, Fithian DC. An algorithm guiding the evaluation and treatment of acute primary patellar dislocations. Sports Med Arthrosc. 2007 Jun. 15(2):78-81.[↩]

- Jain NP, Khan N, Fithian DC. A treatment algorithm for primary patellar dislocations. Sports Health. 2011 Mar;3(2):170-4.[↩]

- Fithian DC, Paxton EW, Stone ML, Silva P, Davis DK, Elias DA, White LM. Epidemiology and natural history of acute patellar dislocation. Am J Sports Med. 2004 Jul-Aug;32(5):1114-21.[↩][↩][↩]

- Beaconsfield T, Pintore E, Maffulli N, Petri GJ. Radiological measurements in patellofemoral disorders. A review. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1994 Nov;(308):18-28.[↩]

- Song EK, Seon JK, Kim MC, Seol YJ, Lee SH. Radiologic Measurement of Tibial Tuberosity-Trochlear Groove (TT-TG) Distance by Lower Extremity Rotational Profile Computed Tomography in Koreans. Clin Orthop Surg. 2016;8(1):45–48. doi:10.4055/cios.2016.8.1.45 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4761600[↩]

- Elias DA, White LM, Fithian DC. Acute lateral patellar dislocation at MR imaging: injury patterns of medial patellar soft-tissue restraints and osteochondral injuries of the inferomedial patella. Radiology. 2002 Dec;225(3):736-43.[↩]

- Smith TO, Donell S, Song F, Hing CB. Surgical versus non-surgical interventions for treating patellar dislocation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Feb 26;(2):CD008106[↩]

- Tsai CH, Hsu CJ, Hung CH, Hsu HC. Primary traumatic patellar dislocation. J Orthop Surg Res. 2012 Jun 06;7:21.[↩][↩]

- Sillanpää PJ, Mattila VM, Mäenpää H, Kiuru M, Visuri T, Pihlajamäki H. Treatment with and without initial stabilizing surgery for primary traumatic patellar dislocation. A prospective randomized study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009 Feb;91(2):263-73.[↩]

- Mäenpää H, Huhtala H, Lehto MU. Recurrence after patellar dislocation. Redislocation in 37/75 patients followed for 6-24 years. Acta Orthop Scand. 1997 Oct;68(5):424-6.[↩]

- Atkin DM, Fithian DC, Marangi KS, Stone ML, Dobson BE, Mendelsohn C. Characteristics of patients with primary acute lateral patellar dislocation and their recovery within the first 6 months of injury. Am J Sports Med. 2000 Jul-Aug;28(4):472-9.[↩]

- Mäenpää H, Lehto MU. Patellar dislocation. The long-term results of nonoperative management in 100 patients. Am J Sports Med. 1997 Mar-Apr;25(2):213-7.[↩]