Pediatric gallstones

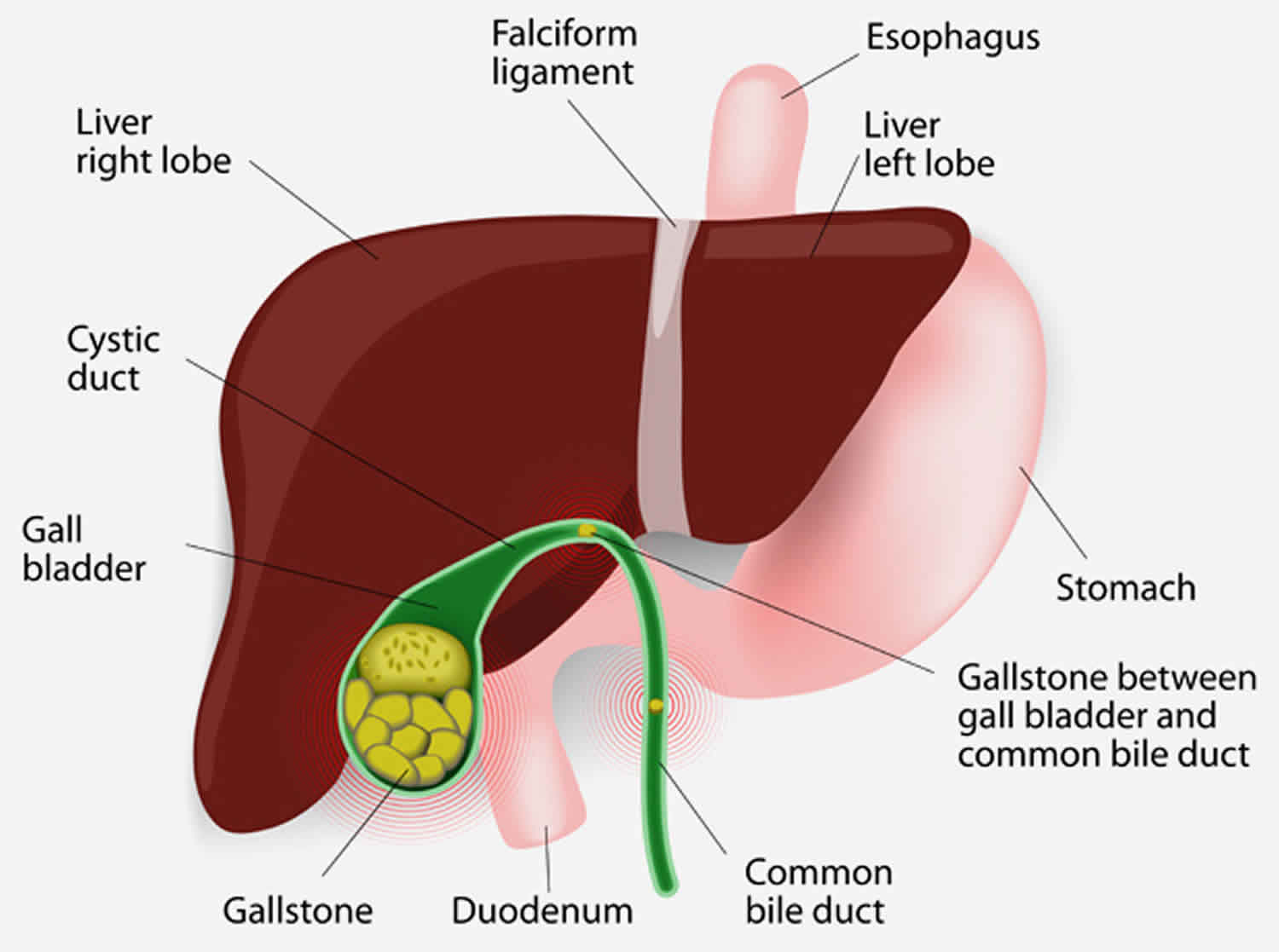

The gallbladder is the place where bile (a liquid made of cholesterol, bile pigments, bile salts, and water) is stored between meals. When your child eats, bile is discharged from the gallbladder into the intestines to help with food digestion. Sometimes, parts of the bile harden and form crystals. When a crystal grows larger, it becomes a gallstone also known as cholelithiasis. Gallstones can block bile from discharging into the intestine.

Gallstones are more common in the adult population and remain relatively uncommon in children; however, the incidence of gallstones in children has increased. A population-based study estimated the prevalence of gallstones and biliary sludge in children at 1.9% and 1.46%, respectively 1. The true number of affected children may have previously been underestimated because patients with cholelithiasis can present with nonspecific abdominal pain.

Although no racial predilection is noted, individuals of certain ethnic heritage have been identified to be at higher risk for developing gallstones, particularly the Pima Indians of North America and Scandinavians.

Prior to puberty, the sex ratio of cholelithiasis in children appears to be equal. However, after puberty, the frequency of cholelithiasis is significantly greater in females than in males and is comparable to the adult ratio of 4:1 female predominance.

Children may present with black pigment, cholesterol, calcium carbonate, protein-dominant, or brown pigment stones 2. Pigment gallstones are the most common type of gallstone in children. They form when bile contains too much bilirubin, a byproduct of the body’s natural breakdown of red blood cells. Cholesterol gallstones are the most common form of gallstone in adults. They form when bile mixes with cholesterol and hardens. Typically, only 1 type of gallstone forms at any given time.

Pain in the right upper quadrant (RUQ) of the abdomen is common. A Murphy sign (expiratory arrest with palpation in the right upper quadrant) is thought to be pathognomonic. Ultrasonography of the right upper quadrant is the study of choice in patients with uncomplicated cholelithiasis. If your child’s doctor suspects gallstones, they will typically order an ultrasound test. Ultrasounds use high-frequency sound waves to produce images of the internal organs.

The morbidity and mortality associated with gallstones are more commonly associated with cholecystitis or ascending cholangitis. The primary morbidity associated with uncomplicated cholelithiasis is chronic abdominal pain, which can be incapacitating.

As in adults, treatment for simple gallstones in children is largely symptomatic, and laparoscopic cholecystectomy remains the criterion standard in treatment for symptomatic cholelithiasis 3.

Pediatric gallstones causes

The cause of gallstones in children isn’t known, but they seem to happen more frequently in some children who:

- Are born prematurely with a low birth weight

- Have experienced spinal injury

- Have a history of abdominal surgery

- Have cystic fibrosis

- Have hemolytic anemia

- Have sickle-cell anemia

- Have an impaired immune system

- Have used intravenous nutrition

- Have a family history of gallstones.

Cholelithiasis in children has various causes related to predisposing factors. Hemolytic disease, hepatobiliary disease, obesity 4, prolonged parenteral nutrition, abdominal surgery, trauma, ileal resection, Crohn disease, sepsis, and pregnancy all may lead to an increased incidence of gallstones in the pediatric population.

Less prominent risk factors include acute renal failure, prolonged fasting, low-calorie diets, and rapid weight loss. Biliary pseudolithiasis, or reversible cholelithiasis, has been identified with the use of certain medications, primarily ceftriaxone 5.

Genetic conditions, such as progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis type 3, can also predispose to gallstone formation. Defects in the in the ABCB4 gene have been increasingly recognized in both adults and children with recurrent cholestasis and cholesterol gallstones 6.

The distribution of gallstone types in children differs from the adult population, with cholesterol stones being the most common type of stone in adults and black pigment stones being the most common type in children 2.

Black pigment stones make up 48% of gallstones in children. They are formed when bile becomes supersaturated with calcium bilirubinate, the calcium salt of unconjugated bilirubin. Black pigment stones are commonly formed in hemolytic disorders and can also develop with parenteral nutrition.

Calcium carbonate stones, which are rare in adults, are more common in children, accounting for 24% of gallstones in children 7.

Cholesterol stones are formed from cholesterol supersaturation of bile and are composed of 70-100% cholesterol with an admixture of protein, bilirubin, and carbonate. These account for most gallstones in adults but make up only about 21% of stones in children 8.

Brown pigment stones are rare, accounting for only 3% of gallstones in children, and form in the presence of biliary stasis and bacterial infection. They are composed of calcium bilirubinate and the calcium salts of fatty acids and occur more often in the bile ducts than in the gallbladder.

The remaining portion of gallstones in children consists of protein-dominant stones, which make up about 5% of gallstones in these patients.

Microliths are gallstones smaller than 3 mm; can form within the intrahepatic and extrahepatic biliary tree; may lead to biliary colic, cholecystitis, and pancreatitis; can persist after cholecystectomy; and are difficult to diagnose as they are often missed on ultrasonography. Biliary sludge is made up of precipitates of cholesterol monohydrate crystals, calcium bilirubinate, calcium phosphate, calcium carbonate, and calcium salts of fatty acids, which are embedded in biliary mucin to form sludge 9.

Pediatric gallstones symptoms

Children with gallstones often experience pain in the right upper or upper middle part of the abdomen. The pain may be more noticeable after meals, especially if the child has eaten fatty or greasy foods. The child also may experience nausea and vomiting. A yellow tint (jaundice) may be noticeable in your child’s skin.

Pediatric gallstones complications

The complications of gallstones in children are similar to those in adults. Cholelithiasis primarily affects the gallbladder and may cause irritation of the gallbladder mucosa, resulting in chronic calculous cholecystitis and symptoms of biliary colic.

If a gallstone obstructs the cystic duct, acute cholecystitis can occur, with distension of the gallbladder wall and possible necrosis and spillage of bile. If gallstones migrate from the gallbladder into the cystic duct and main biliary ductal system, further complications can occur, such as choledocholithiasis, biliary obstruction with or without cholangitis, and gallstone pancreatitis.

Pediatric gallstones diagnosis

The workup of gallstones in children is similar to that in adults. The goal is to demonstrate evidence of gall bladder or biliary tract disease. Laboratory tests should include a complete blood count, gamma-glutamyltransferase (GGT), amylase, urinalysis, direct and indirect bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase, and transaminase levels.

All laboratory results in simple gallstones should be within reference ranges. They are of use in identifying more complex disease processes, including biliary obstruction and cholecystitis. Abnormal results on liver function tests or complete blood count (CBC) suggest infection, obstruction, or both.

Ultrasonography of the right upper quadrant is the study of choice in patients with uncomplicated cholelithiasis. Ultrasonography can be used to identify the location of the gallstone, gallbladder wall thickening, the presence of gallbladder sludge, and pericholecystic fluid. Furthermore, an ultrasonographic Murphy sign (expiratory arrest with pressure from the sonographic probe in the right upper quadrant) aids in the diagnosis of cholelithiasis.

Plain radiography, radionuclide scanning, and cholangiopancreatography can also play a role in the assessment of cholelithiasis. Radionuclide scanning, such as with iminodiacetic acid (IDA) derivatives (eg, hepatoiminodiacetic acid [HIDA], diisopropyl iminodiacetic acid [DISIDA], and para-isopropyliminodiacetic acid [PIPIDA] scanning), is also used to assess gallbladder filling and bile excretion, particularly in response to cholecystokinin or a fatty meal.

In children with suspected hepatobiliary complications, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) 10 or endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) can help delineate the anatomy of the extrahepatic and intrahepatic biliary tract, identify the presence of ductal stones, and provide a therapeutic mode of removing a stone or decompressing the biliary tract 11.

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) in the pediatric population has been associated with the same frequency of success and complications as in adults. As a noninvasive alternative, the magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) has demonstrated promise in the evaluation of gallstones in the bile duct (choledocholithiasis).

Pediatric gallstones treatment

If your child has gallstones but no symptoms such as pain or vomiting, they may not need treatment. Pay attention and be ready to bring your child to the doctor if they develop symptoms later.

In most cases where children develop gallstones, the gallbladder must be removed. This operation is called a cholecystectomy. This is because gallstones often redevelop in the gallbladder if it is not removed. In many cases, gallbladder removal can be performed laparoscopically, which uses smaller incisions, thus allowing your child to recover more quickly and comfortably. Without the gallbladder, the liver will discharge bile directly into the intestine.

In some cases, after the gallbladder has been removed, gallstones redevelop in the bile duct. If this occurs, a procedure called endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) may be performed. During an endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), the gallstone is removed through a flexible tube passed through the mouth, stomach, and intestine, and then into the bile duct.

Both of these procedures require general anesthesia and, typically, an overnight stay at the hospital to be monitored. Both procedures cause considerably less pain and scarring than traditional open surgery.

In rare cases, an “open” procedure through an incision below the ribs may be necessary. This may be required if there is scarring, inflammation, bleeding or unusual anatomy of the common bile duct which prevents safe performance of the laparoscopy.

Pediatric gallstones prognosis

The prognosis for simple gallstones is favorable.

The lag time between the discovery of gallstones in asymptomatic patients and the development of symptoms is estimated at more than 10 years.

- Wesdorp I, Bosman D, de Graaff A, Aronson D, van der Blij F, Taminiau J. Clinical presentations and predisposing factors of cholelithiasis and sludge in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2000 Oct. 31(4):411-7.[↩]

- Pediatric Gallstones (Cholelithiasis). https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/927522-overview[↩][↩]

- Bonnard A, Seguier-Lipszyc E, Liguory C, et al. Laparoscopic approach as primary treatment of common bile duct stones in children. J Pediatr Surg. 2005 Sep. 40(9):1459-63.[↩]

- Bonfrate L, Wang DQ, Garruti G, Portincasa P. Obesity and the risk and prognosis of gallstone disease and pancreatitis. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2014 Aug. 28 (4):623-35.[↩]

- Prince JS, Senac MO Jr. Ceftriaxone-associated nephrolithiasis and biliary pseudolithiasis in a child. Pediatr Radiol. 2003 Sep. 33(9):648-51.[↩]

- Nakken KE, Labori KJ, Rodningen OK, et al. ABCB4 sequence variations in young adults with cholesterol gallstone disease. Liver Int. 2009 May. 29(5):743-7.[↩]

- Stringer MD, Soloway RD, Taylor DR, Riyad K, Toogood G. Calcium carbonate gallstones in children. J Pediatr Surg. 2007 Oct. 42(10):1677-82.[↩]

- Koivusalo A, Pakarinen M, Gylling H, Nissinen MJ. Relation of cholesterol metabolism to pediatric gallstone disease: a retrospective controlled study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2015 Jun 30. 15:74.[↩]

- Svensson J, Makin E. Gallstone disease in children. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2012 Aug. 21(3):255-65.[↩]

- Dalton SJ, Balupuri S, Guest J. Routine magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography and intra-operative cholangiogram in the evaluation of common bile duct stones. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2005 Nov. 87(6):469-70.[↩]

- Rocca R, Castellino F, Daperno M, et al. Therapeutic ERCP in paediatric patients. Dig Liver Dis. 2005 May. 37(5):357-62.[↩]